Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Evolution: Economic and Agriculture Development in Sub-Saharan Africa

Uploaded by

NovusOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Evolution: Economic and Agriculture Development in Sub-Saharan Africa

Uploaded by

NovusCopyright:

Available Formats

Economic and Agriculture Development in sub-Saharan Africa

Written by: Dr. Giovanni Gasperoni Tricia Bentley-Beal

Published February, 2011

Evolution:

Executive Summary

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Agriculture is the backbone of overall growth for the majority of countries in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and is essential for poverty reduction and food security in the future. It is critical for countries in SSA to embrace the potential of agriculture as a means to grow their economies, to become self-sufficient and to diminish the threat of food insecurity. This potential will be limited if agricultural policies that have been crafted by and for mature economies are adopted. SSA is classified, in economic terms, as a developing region of the world. A strong agriculture industry for SSA will not materialize without concerted and purposeful policy action that is tailored to the current state of economic and infrastructure development. Sound policy should be based on the true needs of a particular country or region of the world -- designed to align with and support that specific economic development. Many of the agricultural policies under consideration in Africa today are based on the regulations of developed and industrialized countries. These may be appropriate for SSA after 10-15 years of positive growth. These policies do not fully consider the technological tools and infrastructure that is needed for Africa to grow in the nearto mid-term. Important Policy Categories for Economic Development in SSA: I. Import Policy II. Support and Development of Small Shareholder Farmers III. Agriculture Education and R&D IV. Empowering Agriculture Best Practices V. Adaptation for Rain Fed Agriculture and Climate Change SSA Today Africa is the only continent where poverty has increased in absolute and relative terms (Collier, Bottom Billion, 2007). One billion people live in Africa and 30% suffer from chronic hunger. In SSA, 38% of children under 5 are permanently stunted as a result of malnutrition (FAO, 2009). In SSA lack of economic growth, based on a range of factors, has made this region more dependent on food imports, which has made it much more vulnerable to the shock of inflating food prices. The failure to grow economically has set back the demographic transition that significantly lowered population growth rates in other parts of the world. Low growth has aggravated the debt crisis and reduced domestic resources for infrastructure, agricultural development, health, education and nutrition. Business climates in Africa still rank low in international comparisons. Transport costs are among the highest in the world. Electricity supplies are unreliable and costly. Financial sectors are underdeveloped, reaching only a few clients with low saving rates. Private input and output markets remain under-developed and farmers continue to be severely penalized by inadequate competition in these markets. Farmers are also subjected to higher input prices and lower farm gate prices than in other regions of the world. Finally, the resulting lack of infrastructure has made an agricultural adaptation to evident climatic changes impossible (Binswanger-Mkhize, 2009).

Executive Summary

Policy Evolution: Economic Development and Agriculture Industries All countries of the world are in varying states of economic development. In some regions, such as Europe and the United States, the state of agricultural evolution has spanned the spectrum from subsistence farming to a mature state with near zero food insecurity. In these mature environments consumer behavior is driven by choice and they demand highly sophisticated, expensive food products. In Europe, the agriculture industry and policies grew over time and as the region developed. As in other parts of the world that have transitioned from developing to developed economies, the pace of growth in Europes agricultural sector depended on specific industrial, political and market conditions. Europe is similar to Africa, in that the region is a conglomerate of many nations and these nations continue to progress at differing levels of economic development. From this perspective, history has proven that as a region develops economically, the most important advances in agricultural production and development occur first at the national level (Lains and Pinilla, Agriculture and Economic Development in Europe Since 1870, 2009). As a region develops economically, the relative importance of agriculture as an industry tends to decline. The primary reason for this was shown by the 19th century German statistician Ernst Engel, who discovered that as incomes increase, the proportion of income spent on food declines. It follows from this that, as incomes increase, a smaller fraction of the total resources of society is required to produce the amount of food demanded by the population. This occurs through industrialization and consolidation of the agriculture industry. The graph below demonstrates this evolution in the United States, Germany and the United Kingdom between the years 1870 1990. As a point of reference, 65-80% of the labor force in SSA is currently employed in agriculture (International Food Policy Research Institute).

Sectoral Shares of Employment in the Sectoral Shares of Employment in the USA, the UK and Germany, 1870-1990 USA, the UK and Germany, 1870-1990

55 50 45 40 35

Percent

30 25 20 15 10 5 0

1870

1910

1920

1930

1940

1950

1973

Years

Germany

UK

USA

Source: from Broadberry (1997b, 1997c, 1998) Source: DerivedDerived from Broadberry (1997b, 1997c, 1998)

1990

Executive Summary

Agricultural policies also evolve as economies develop and the developmental needs of a country or region evolve. We have witnessed this very clearly with the European Union. Subsistence farming was still present across many parts of Europe up until World War I. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) was established as part of the Treaty of Rome in 1957, which established the Common Market. In the beginning of the Common Market, the original 6 member states maintained strong individual policies in their agricultural sectors. These policies were particularly evident in regards to what was produced, the pricing of goods and how farming was organized. Over time the member states wanted to advance towards the benefits of free-trade. The only way to achieve this relationship was to begin to harmonize their policies. In 1962, three major principles were established as underlying elements of the CAP: market unity, community preference and financial solidarity. Since then, the CAP has been a central element in the European institutional system. In the beginning, the CAP had a strong focus on traditional farm subsidies and on increasing production to meet the demands for food. In the early 1990s, the CAP placed a new emphasis on environmentally sound farming. Farmers had to look more to the market place, while receiving direct income aid, and to respond to the publics changing priorities. Additionally, a new rural development policy encouraged many initiatives which helped farmers to restructure their farms, to diversify and to improve their product marketing. Current CAP policies are demand driven. They take consumers and taxpayers concerns, who are wealthy by world standards, fully into account. Today, farmers still receive direct income payments to maintain income stability, but those who fail to meet the production standard policies of CAP face reductions in their direct payments. CAP policies in the new millennium are very much geared towards the consumer-driven demands of a wealthy economy: environment, food safety, phyto-sanitary and animal welfare standards. Specific Policy for Regional Needs In Europe, the status of economies varies among nations but these are largely growing at a strong level or are mature. European farmers have benefited from decades of support that has provided subsidy and established markets, transportation and production infrastructures. European farmers are in a better position to adopt and comply with the mandated policies which restrict their operational practices. Developing countries have different agricultural development needs and policy requirements than mature countries. In developing countries and regions, particularly SSA, there is generally a need to establish core infrastructures, educate industry stakeholders and integrate best technologies with indigenous practices. Consumers in developing economies, in many cases, are concerned about having the ability to purchase enough food to feed themselves and their families. The policies of mature countries are crafted against and relevant for an agriculture industry that is well-established, well-tooled and highly functioning. These countries have already moved through and past the state of development of SSA. Adopting their policies can have a putting the cart before the horse effect, with the danger of hindering development of the agriculture industry and the region.

SSA Population Trends

SSA POPULATION TRENDS SSA has unique circumstances in relation to the demographics of its population - a high growth rate combined with a disproportionate number of dependent, young people. The population of SSA increased from 100 million in 1900 to 770 million in 2005. Despite a devastating HIV and AIDS epidemic, the population growth remains at nearly 2% per year (versus the aggregate world growth rate of 1%), with growth projected to remain at a rate of 1.9% to 2015 (United Nations, 2006). Globally, fertility rates and decreasing population growth transition can be linked to income increase, urbanization, girls education and reduced child/infant mortality rates. This population transition and population growth decrease in SSA has been delayed because of stagnant economic growth rates. This is one of the main reasons SSAs population growth rate has not declined as fast as in Asia (Binswanger-Mkhize, 2009). The graph below illustrates Africas population growth in relation to the rest of the world:

World Population Growth, 1996-2005 and 2006-2015

Source: United Nations 2006

A very important reason for poor investment incentives and returns in SSA is that the demographic transition began later and is happening at a slower rate than elsewhere in the world. The current situation results in a high level of age dependency. The delayed demographic transition in SSA consistently predicts two-thirds of the difference in economic growth performance with the rest of the developing world (Ndulu, 2007). Lower life expectancies are also shown to contribute to the poorer economic growth performance, which has been compounded by the AIDS epidemic. Today there is a 4% per capita income growth rate in SSA, meaning the population transition will begin to accelerate over the next decade. A decline in population growth in SSA will reduce dependency rates and lead to a demographic profile for the region, where there is a larger adult labor force with smaller populations of children and youth. Currently in SSA there are over 200 million people between 12 and 24 years of age. Compounding this, in Kenya for example, the probability that a 20 year old may die before age 40 is 36% and would drop to 8% with the absence of HIV/AIDS (FAO, 2009). Education opportunities for this large, young population are weak. Underdeveloped primary school programs lead to high dropout rates and a large percentage of illiteracy. Development policies should include generating education programs which lead to productive employment for this population. Agriculture with high employment intensity, both directly and through urban linkage effects, should be a high priority in this programming.

Import Policy

I. IMPORT POLICY After the end of colonization, many SSA countries started to discriminate against agriculture through overvalued exchange rates, industrial protection and direct agricultural taxation. A major study has now measured the combined effects of these three interventions on the net rate of agricultural assistance and compares them across the developing and developed world (Anderson and Masters, 2009). A negative rate of protection is in fact the rate of taxation. This is often referred to as dis-protection. The graph below considers Africa as a whole and illustrates that the net protection rates have improved from approximately -20% in 1975 to 1979 to less than -10% in the first half of this decade. (Binswanger-Mkhize, 2009).

Nominal Rates of Assistance to Exportable, Import-Competing and All Agricultural Products, African Region 1955-2004

Source: Anderson and Masters 2009

As the graph above shows, the anti-trade bias against agriculture has been focused on exportable commodities (approximately 40% in the 1970s), with importables being generally protected to a small degree. Although improvements have occurred in relation to dis-protection, rates remain at nearly 20% for exportables today. Within SSA, the greatest improvements have been in regards to dis-protection in Kenya, Mozambique, Madagascar, Uganda and Cameroon (Binswanger-Mkhize, 2009). Projections to 2050 tend to confirm that this import dependency will continue in many African countries and this issue is compounded by low levels of intra-regional trade resulting from physical and governmental barriers. African farmers have the greatest opportunities for growth in domestic and regional markets. This potential is the greatest due to a combination of factors including: higher world prices, rapid demand growth associated with population growth, urbanization and income growth. In these markets, farmers compete at import parity prices rather than at the lower export parity prices, and they face lower phyto-sanitary and quality challenges than in overseas markets. Through import substitution, African farmers have the opportunity to re-conquer markets lost to imports in the previous 45 years. Africa can look to the benefits of export market opportunities in the long run after developing their domestic and regional markets. Mobilizing the agriculture industry in SSA to supply the demand of domestic and regional markets is dependent upon policies which continue the reduction of dis-protection, leveling the playing field for vast numbers of small shareholder farmers. Small shareholder farmers represent the majority of the agriculture workforce in SSA and if properly supported and developed, they have the power to make the region self-sufficient in relation to food, drive economic development to a new level and raise millions of people out of hunger and poverty.

Support and Development of Small Shareholder Farmers

II. SUPPORT AND DEVELOPMENT OF SMALL SHAREHOLDER FARMERS Empowering small shareholder farmers to move their businesses and communities ahead will require the policy designed to develop well structured institutions which can address the primary needs of this sector including: education, infrastructure, financing and resource management. If small shareholder farmers receive the appropriate support, SSA could be moved closer to solutions, including: Increased farm profits and investments Re-conquest (from imports) of domestic and regional markets Reduced food insecurity and malnutrition

(Binswanger-Mkhize, 2009)

No single institution by itself can carry the burden of local and rural development; the structure for support to farmers must be multi-disciplinary. The model should integrate the private sector, civil society, local government and the sector institutions such as health, education and agriculture (World Bank, 2004). The majority of the worlds 2.1 billion people who live on less than $2 per day live in rural areas and depend on agriculture for their livelihood. Agriculture growth can have a dramatic impact on poverty reduction. Over the past 10 years global poverty, with a $2 per day poverty line, declined by 8.7% in absolute numbers. This decline was caused entirely by rural poverty reduction, with agriculture as the main source for growth (The World Development Report, 2008). In Africa, there are 33 million small farms of less than 2 hectares , representing 80% of all farms on the continent. Equipping these farmers with the knowledge and tools to make their farms successful is a crucial key to increasing the pace of economic development in SSA.

How Agricultural Growth Reduces Rural Poverty

1. By raising agricultural profits and labor income 2. By raising rural non-farm profits, employment and labor income via linkage effects 3. By causing lower prices of (non-tradable) foods, especially beneficial for the poor 4. Lower food prices reduce urban real wages and accelerate urban growth 5. Tightening urban and rural labor markets raise unskilled wages economy-wide

Source: Johnson and Mellor, 1961

Agriculture has a much more direct impact on hunger than general economic growth and countries with faster agricultural growth have made more progress against hunger (Pingali, 2007). For example, hunger has declined in West Africa, and it has increased significantly in coup or conflict countries. A key issue that has surfaced and one that perhaps is relatively accessible to address is a lack of agriculture research, education and extension to support development.

Agriculture Education and R&D

III. AGRICULTURE EDUCATION AND R&D (In Africa,) we need to blur the differences between research and extension, -Pedro Sanchez, Winner of the World Food Prize, 2002

Success in agriculture depends crucially on the indigenous scientific capacity to generate new technologies. Africa in general invests significantly less in agriculture education than other regions of the world. Africas large public research system includes over 400 institutions, but they are small. The 3000 agricultural scientists in Africa are not as well trained as those in other regions and they also have fewer resources to work with. The agricultural science education system is similarly fragmented into 200 institutions and they are, on average, poorly funded. Due to enormous challenges from pests, diseases and water stress, basic scientific innovations and best practices are needed for a wide variety of crop and livestock challenges (Binswanger-Mkhize, 2009). The goal should be to create an integrated system of agricultural research, extension and education that is responsive and accountable to farmers, agribusiness and consumers. Currently, SSAs agricultural research institutes and education extension services have very little capacity to engage in new scientific research or to push existing technologies to the farm level. In part, such problems can be overcome by finding new ways to generate and handle scientific knowledge, such as internet and wireless phone technologies. Additionally, including farmers that are more closely involved in both research and dissemination has proven effective in various models including Farm Field Schools (FFS). Lack of supportive policy, government investment and private sector financing are major challenges for research and extension services. Education and Extension Investing in human capital is one of the most effective means of reducing poverty and encouraging sustainable development. Agricultural education, extension and training programs ensure that information on new technologies and best practices reaches farmers in their own communities. Extension is the means by which new knowledge and ideas are introduced into rural areas in order to bring about change and improve the lives of farmers and their families. Successful extension services begin at the governmental level through the creation of supporting policy, cascade down through technology transfer and finally, the ultimate success, technology utilization. The policy component of extension service relates to government development goals and strategies, market and price policies and the levels of resource investments in the system. The policy structure determines the framework for research and development, the process for transfer and assessment of utilization uptake. Technology transfer is the process of evaluating and adapting research outputs for users and then widely disseminating this knowledge through education of target adopters. Technology Utilization encompasses the farmers awareness, adaptation and adoption of technology effectively at the farm-level, increasing productivity and profitability and, ultimately, economic growth at the national level.

Empowering Agriculture Best Practices

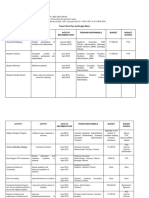

IV. EMPOWERING AGRICULTURE BEST PRACTICES In developing regions of the world where small farm operations are still common and widespread, conditions are variable, infrastructure can be limited, raw materials are often low quality and animal nutrition programs are not optimized due to lack of resources. The level of industrialization of an operation directly and drastically impacts animal performance. The good news is that many fundamental practices of industrialized agriculture can be applied at the small farm level. What is fortunate for the developing region of SSA is that many countries with successful agriculture industries and infrastructure models have moved through the regions existing state of development and developed the necessary technologies along the way. Adoption of simple, yet fundamental best practices by farmers will reap dramatic returns on investment. The pace of technology adoption is important to long-term success. SSA should set the basic foundation of best practices and then transition incrementally to higher technology models. A fundamental challenge in achieving productivity growth in Africa is the fragmented nature of the small shareholder farmer system, the variety of agro-ecological environments and the diverse farming systems/practices. Under such conditions, the possibility for application of existing best practice technologies or the massive application of new ones are limited. However, success stories of technology generation do exist and lessons should be drawn from such successes. Livestock Nutrition In SSA, many times a farmers dairy cow or chicken flock is the familys single largest asset and represents their primary food source. Depending on an animals health and output is a precarious position for financial and food security. A lack of knowledge and tools prevents a large majority of farmers from sustaining the health of their animals and extending this investment to improve their quality of life. Low productivity occurs in the absence of balanced nutrition and contributes to poor animal health. The table below illustrates how Africa compares against other countries in relation to productivity.

Broilers & Tilapia - Kgs Feed/1 Kg Protein Produced Dairy - Milk Kg Production Per Day

Livestock Productivity

Brazil 1.65 1.6 23

Speicies Broiler Tilapia Dairy

US 1.6 1.6 34

Thailand 1.65 1.6 10

Africa 2.6 2.5 5.0

Source: Novus Analysis, 2010

Empowering Agriculture Best Practices

The United States, Brazil and Thailand are raising the majority of their livestock in industrialized environments where best practice nutrition is being applied. These best practices can be scaled down to the farm level, empowering SSA Farmers to increase the productivity of their livestock. Nutritional Best Practices Include: Optimizing Feed Utilization Optimizing Feed Costs Enhancing Reproductive Performance Reducing Feed-Borne Pathogens Supporting Optimal Digestive Health Preventing Feed Toxins Treating and Preventing Disease (anti-microbial growth promoters) Feed Utilization Methionine is an essential amino acid. Amino acids are the building blocks of protein, which make feed more nutritious and efficient. Very simply stated, animals will be limited in their growth and productivity without proper amounts of methionine. It is the first limiting amino acid in poultry and the second limiting amino acid for ruminants and pigs. Achieving amino acid balance in an animals diet through feed alone is very difficult. A fundamental best practice is the incorporation of synthetic amino acids, which allows farmers to feed their livestock with greater efficiency and at a lower overall formulation cost. Lowering Feed Costs In addition to amino acid balance, another best practice to lower feed costs is the application of enzyme technology. Feed ingredients are an enormous investment for farmers. All animals naturally produce enzymes that break down major nutrients, including protein. However, animals are not capable of breaking down some components that naturally occur in animal feed such as fiber or phytic acid, which means that nutrients are not absorbed and feed is wasted. When an animals diet is supplemented with enzymes, the digestion of nutrients is optimized, leading to improved animal health and lower operating costs. In a corn/soy diet for poultry, for example, approximately 90% of the feed is digestible, while 10% is converted to waste matter. By maximizing the digestible portion of the feed, farmers can recognize a higher return on their investment. Enhancing Reproductive Performance One dairy cow provides a single source of income for many SSA families, but this is a risky financial position to be in. If a familys cow successfully reproduces, the prospect of a sustainable income increases. Reproductive issues can significantly impair the ability of farmers to produce a steady income stream from selling dairy cows and can limit their ability to supply their local communities with dairy products. A simple combination of minerals, vitamins, organic acid blends and mycotoxin binders can substantially increase the reproductive health of dairy cows.

Empowering Agriculture Best Practices

Feed-Borne Pathogens and Toxins In developing countries, producers are often forced to create diets based on a limited selection of low quality feed ingredients. It is typical in these regions for ingredients to lose nutritional value due to aging and the aSSAciated challenges. Mycotoxins are one example of a feed-borne which can impact livestock and people. Mycotoxins are a common feed-borne toxin, especially prevelant in warm climates. Mycotoxins vary throughout the world, with different regions experiencing different mycotoxin-related challenges. The highest risk to human health is in developing regions such as SSA, where pasteurization is not yet widely adopted. In these areas, the aflatoxin M1 is of widespread concern. When cattle consume aflatoxin, the milk they produce quickly becomes contaminated with M1, which can ultimately have devastating health effectsincluding death of animals and of people who consume their products. A best practice related to mycotoxin management is the use of anti-caking agents which bond with mycotoxins inside of the animals and safely carry them out through the animals waste. Disease Prevention and Treatment Anti-microbial growth promoters have received a high level of attention, particularly in mature and wealthy markets, over the past few years due to concern over anti-microbial resistance. There has never been a single case where a resistant human infection has proven to be caused by use of antimicrobials in food-producing animals. Cases of resistant human infection are seen more frequently with pathogens transmitted between humans (such as extremely drug resistant tuberculosis, also called XDRTB, and MRSA). In food production systems, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approves the use of antimicrobials for four purposes: Growth promotion/feed efficiency: the antibiotics are administered, usually in feed, to in crease growth rates and improve feed efficiency. The goal of this is to maximize production from the animals. Prevention of disease: there is a known disease risk present and the antibiotics are administered to prevent infection of animals. Control of disease: disease is present in a percentage of a herd or flock and antibiotics are administered to decrease the spread of disease in the flock/herd while clinically ill ani mals are treated. Treatment of disease: the antibiotics are administered to treat sick animals. Growth promoters with an anti-microbial activity, when mixed into the feed, have been used for decades and they have contributed substantially to increasing poultry, swine and cattle production and efficiency. This has helped developing economies and agriculture systems to prosper and to become globally competitive.

10

Empowering Agriculture Best Practices

Livestock Genetics A combination of genetics and nutrition have taken the protein industry a long way over the past decades in regards to increased protein output through increased weights. In additon to increasing livestock productivity, genetics can help farmers with issues such as disease resistance and feed conversion improvement. When comparing all sources of protein, poultry is the most efficient, economical source on earth. In the 1960s through the 1980s, most of the focus of genetics technology in the broiler industry was on selection programs with criteria that were relatively easy to measure, including: egg production, hatchability, growth rate and feed conversion. In 1988 the average weight of a broiler was approximately 2 kgs. Today the average weight is nearly 3 kgs. Broiler weights are projected to continue to increase yearly over the next decade at a rate of 0.06%. Weight increases have been achieved through the strategic application of genetic technologies and nutritional supplementation, which enable livestock to reach their maximum weight potential. Proper nutrition and amino acid supplementation are fundamental to achieving genetic potential. The photograph below illustrates the genetic improvements in poultry over the past four decades.

1970

2008

Housing and Management Systems Providing housing to protect livestock from the elements, predators and to prevent the spread of disease is a fundamental best practice for maintaining animal health. Housing can be basic and inexpensive and the most important considerations are related to managing the hygiene of the environment. Ventilation systems in livestock housing serve an important function - maintaining a comfortable and healthy animal environment. The primary purpose of a ventilation system is air exchange. Ventilation is needed to remove excess heat, dust particles and moisture produced during normal activities such as metabolism, respiration and evaporation. Additionally, these systems remove harmful gases and disease causing organisms. Another aspect of hygiene to promote animal health is waste management. In the example of poultry, proper litter conditioning is an essential component for keeping flocks healthy and profitable for farmers. Conditioning litter between flocks addresses where the birds live, which is the most crucial aspect of the poultry house environment. Ideal litter is loose and free flowing (friable), not too dry or too wet, low in ammonia, uniform particle size and contains a minimum load of insects (Watkins, 2001).

11

Empowering Agriculture Best Practices

Raw Materials For a region like SSA that is import-dependent for agricultural commodities, the severe price increases of raw materials over the past decade are devastating. The map below illustrates Africas competitive status for corn production in comparison to rest of the world:

Global Corn Acres Sub Optimized: Corn Productivity Indicators

Source: USDA FAS, Novus Analysis, 2009

Prices of raw materials have been volatile over the past decade. Since early 2002, fluctuations in production, trade and stocks of agricultural commodities have been unusually large. Over this period, an index of monthly-average world prices of wheat, rice, corn and soybeans rose 237%, then declined 40% and in late 2009 stood at about 115% above the January 2002 level. (USDA, 2010). From January 2002 to mid2007, the price index of these four commodities rose 79%. The graph below illustrates the volatility in raw material prices over the past decade.

Raw Material Prices 2002-2008

Corn, Soya and Oil

12

Source: CME Group, 2009

Empowering Agriculture Best Practices

A number of factors contributed to the increase in raw materials: Strong global economic growth and rising per capita incomes stimulated demand. Slower trend growth for crop yields were followed by weather-reduced harvests in a number of major producing regions in 2006 and 2007, constraining production. Rising energy prices increased costs of production, processing, transportation for agricul tural products and also stimulated production of biofuels. The value of the U.S. dollar declined, which put upward pressure on commodity prices de nominated in dollars. The allocation of U.S. corn stocks toward ethanol production rose from 10% in 2002 to 31% in 2008. SSA has the necessary natural resources to generate their own raw materials for use in food for people and feed for animals. What is lacking are best practices related to crop technology. Crop Technology Africa is a continent rich in natural resources, both land and water. Yet there is a high prevelance of food insecurity, import dependence and low output farming. Currently, Africa is only using 32% of its potential arable land. The adoption of best practice crop technology can play an important role in moving SSA towards a higher level of development and self-sufficiency. Fertilizer Land degradations caused by nutrient depletion, soil erosion, salinization, pollution, overgrazing and deforestation are clearly major issues in SSA agriculture. Smallholders have removed large quantities of nutrients from their soils without applying sufficient quantities of manure or fertilizers to replenish the soil (InterAcademy Council). Dramatic increases in fertilizer prices over the past few years have compounded the soil degradation issue in SSA. World fertilizer prices surged by more than 200% in 2007, as farmers sought to maximize corn production for ethanol and poor African farmers were hit the hardest by the increase (International Center for Soil Fertility and Agricultural Development, 2009). The rise in fertilizer prices was fueled by new demand for grain for biofuel production, higher energy and freight prices, increased demand for grain-fed meat in emerging markets and increased use of natural gas as liquefied natural gas (LNG). From January 2007 to January 2008, diammonium phosphate (DAP) prices rose from $252 to $752 per ton (U.S. Gulf price), prilled urea rose from $272 to $415 per ton (Arab Gulf price) and muriate of potash (MOP) rose from $172 to $352 per ton (Vancouver price). At the same time the price of 1 metric ton of corn rose from $3.05/bushel to $4.28/bushel. Seed Adaptation through the use of biotechnology can be a key tool for African farmers as they work to manage their businesses in the face of climate change. Seed technology, in particular drought resistant genetically modified (GM) seeds, can play a significant role in countries where crops are rainfall dependent. In the next section of this paper Adaptation for Rain Fed Agriculture and Climate Change, the best practice of GM seed usage is examined.

13

Adaptation for Rain Fed Agriculture and Climate Change

V. Adaptation for Rain Fed Agriculture and Climate Change 90-95% of food production in Africa is rainfall dependent. Unlike Asia, where two dominant food crops are grown in large homogenous areas under irrigation, there has been no investment in dominant farming systems of this kind in Africa (Akaki, 2003). Man-made climate change has become accepted as a mainstream environmental concern. The negative aggregate impact of climate change on African agriculture spanning to the 2080-2100 time period is expected to be between 15-30% reduction in productivity (Binswanger-Mkhize, 2009). For African farmers, the adaptation challenges are clear: Increase in agronomic complexity Increase in risks of shocks based on adverse weather patterns at the farm and community level Modifications to cropping patterns, timing and seed requirements Observed temperatures have increased across wide areas of the world and it is predicted that with greenhouse emissions at current or higher levels than in the past, temperature changes during the 21st century will be faster than in the 20th century, ranging between 1.4 - 5.8 degrees Celsius (Binswanger-Mkhize, 2009). SSA contributes the least to greenhouse gas emissions, yet is expected to be among the most negatively affected by climate change. Increases in extreme weather events may reduce food production. Potential adaptation to climate change could significantly reduce negative impacts. However, countries that do not have the capacity to adapt will be highly vulnerable to extreme events. Climate change will have varying impacts around the world. There will be major gains in agriculture potential in North America (20-50%) and in the Russian Federation (40-70%), whereas a potential 9% loss is predicted for SSA (IPPC, 2007). The map below illustrates predicted gains and losses of productivity spanning to the 2080 time period:

Likely Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture and Forestry Across the World

14

Source: IPCC, 2007

Adaptation for Rain Fed Agriculture and Climate Change

Land Usage Less than a quarter of the total land area of SSA that is suitable for rain fed crop production is used. FAO has estimated that the potential additional land area available for cultivation amounts to more than 700 million hectares. Experts point in particular to the Guinea Savannah region an area twice as large as that planted with wheat worldwide. Only 10% of the Guinea Savannah, covering an estimated 600 million hectares, is farmed (FAO, 2009). The agro-ecological conditions are rather similar to the Cerrado region of Brazil, which has been an engine of agricultural growth in that country. But at the same time, it must be recognized that to benefit from this natural resource and open up new farmlands will require enormous investments in infrastructure, technology and an intra-regional policy approach. The map below illustrates the region of the Guinea Savannah:

Source: FAO 2010

15

Adaptation for Rain Fed Agriculture and Climate Change

Biotechnology Adaptation Africas reliance on agriculture and its very low levels of irrigation make the region vulnerable to weather variability and climate change. Drought resistant GM seeds have proven successful in many parts of the world where weather is a challenge and they offer great potential for SSA. The issue of the safety of GM seeds has been discussed since the introduction of the first genetically modified crop in 1996. Reputable organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S. National Academies of Science have issued numerous reports on the safety of GMOs. In June 2005, for instance, WHO released a report entitled Modern Food Biotechnology, Human Health and Development, which reaffirmed the safety of GM foods. The U.S. National Academies of Science has, on numerous occasions, cautioned against condemning GM crops on the basis of non-scientific evidence. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), a reputed nonpartisan organization, recently released the statement in regards to GMOs, No specific scientific evidence, in terms of risk to human and animal health and the environment, is provided that would justify the invocation of a safeguard clause. The challenge for policymakers in Africa is to make an open and honest assessment to understand the potential benefits of GM technology, the benefits that GMOs have proven in other parts of the world and to establish what opportunities it presents for Africa. Cereal yields have grown little in SSA and today are around 1.2 MT per hectare, compared to an average of 3 MT per hectare in the developing world where GMO technology is widely adopted.

16

Conclusion

CONCLUSION The most important point of this paper is that investments to create policy should be focused on the issues that will make the difference for a specific country or region as they relate to the evolution of economic development. It is critical for countries in SSA to embrace the potential of agriculture as a means to grow their economies, to become self-sufficient and to diminish the threat of food insecurity. This potential will be limited if agricultural policies are adopted which have been crafted by and for mature economies. Important Policy Categories for Economic Development in SSA: I. Import Policy II. Support and Development of Small Shareholder Farmers III. Agriculture Education and R&D IV. Empowering Agriculture Best Practices V. Adaptation for Rain Fed Agriculture and Climate Change Import Policy African farmers still face the worst agricultural incentives in the world. Though there have been improvements against taxation, policy reform can better position SSA farmers to compete and prosper. Through import substitution, African farmers have the opportunity to re-conquer markets lost to imports in the previous 45 years. Support and Development of Small Shareholder Farmers Empowering small shareholder farmers to move their businesses and communities ahead will require the policy designed to develop well structured institutions which can address the primary needs of this sector including: education, infrastructure, financing and resource management. Agriculture Education and R&D Africa in general invests significantly less in agriculture education than other regions of the world. Currently, SSAs agricultural research institutes and education extension services have very little capacity to engage in new scientific research or to push existing technologies to the farm level. This can only be addressed through policy which supports effective technology transfer/education programs which lead to technology utilization. Empowering Agriculture Best Practices SSA should follow the lead of the many countries with successful agriculture industries and infrastructure models that have moved through the regions existing state of development and developed the necessary technologies along the way. Adoption of simple, yet fundamental best practices by farmers will reap dramatic returns on investment. Adaptation for Rain fed Agriculture and Climate Change Adaptation of practices and infrastructure to cope with ongoing climate change and adverse weather events is imperative for sustained agricultural growth in SSA. Biotechnology related to seed technology and access to arable land can both play a critical role in the adaptation process.

17

Conclusion

Food Security and Agriculture There is no question that the clock of history is moving swiftly. Already a tragic and growing imbalance exists between the worlds agricultural output and its population. Until the population is stabilized, every increase in food production is an important holding action. In effect, we are buying time until the scales of survival can be brought into lasting balance - John D. Rockefeller, Conference on Subsistence and Peasant Economics, 1965

SSA is one of the most food-insecure regions in the world. In the region as a whole, more than 40% of people are undernourished, and in Eritrea and Somalia the proportion rises to 70%. The seven countries of the region - Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Somalia, the Sudan and Uganda - have a combined population of 160 million people, 70 million of whom live in areas prone to extreme food shortages. Over the past 30 years, these countries, which are all members of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), have been threatened by famine at least once each decade. Even in normal years, the IGAD countries do not have enough food to meet their peoples needs. In four of them - Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia - the average per capita dietary energy supply (DES) is now substantially less than the minimum requirement. In these precarious circumstances, any external shock, be it a drought, a flood, an invasion of migratory pests or livestock disease can push large numbers of people over the edge. Total national food production may not fall by much; even in the worst famine years, aggregate national production has only dropped to about 7% below the long-term average. But for the poorest communities, the effects can be disastrous, as families that had insufficient food to start with suddenly find themselves with none at all. These are the reasons that policies related to supporting the development of a more resilient agricultural industry are urgent and necessary. Policies relevant to SSA are the key to success: support small shareholder farmers in operating profitable and sustainable businesses, provide connections to educational extension services and access to the transfer of technologies and best practices that will spur long-term economic development for the region.

18

References

REFERENCES Akaki 2003, Selected Issues in Agricultural Policy Analysis with Special Reference to East Africa Binswanger-Mkhize, H.P. 2007. Drivers of Growth and Competitiveness in Commercial Agriculture Binswanger-Mkhize, 2009 Challenges and Opportunities for African Agriculture and Food Security Binswanger-Mkhize, Hans P., and A. McCalla, 2009, The Changing Context and Prospects for Agriculture and Rural Cevelopment in Africa Collier, Paul 2007. The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries are Failing and What Can Be Done About it. FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). 2008. Soaring Food Prices: Facts, Perspectives, Impacts and Actions Required. FAO, 2009. Global Agriculture Towards 2050 FAO, 2009. The Special Challenge for sub-Saharan Africa IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). 2007. Climate Change: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Lains-Pinilla, 2009. Agriculture and Economic Development in Europe Since 1870 Ndulu, Benno, with Lopamudra Chakraborti, Lebohang Lijane, Vijaya Ramachandran, and Jerome Wolgin, 2007. Challenges of African Growth: Opportunities, Constraints and Strategic Directions Pingali, Prabhu, Kostas Stamoulis, and Gustavo Anriquez. 2007. Poverty, Hunger and Agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa: Opportunities and Challenges United Nations, 2006, World Population Prospects, Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat World Bank. 2006. World Development Report 2007: Development and the Next Generation World Bank. 2007. World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development

19

Novus International, Inc. 20 Research Park Dr. St. Charles, MO 63304 1.888.906.6887 www.novusint.com

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Planning For Agritourism: A Guide or Local Governments and Indiana FarmersDocument11 pagesPlanning For Agritourism: A Guide or Local Governments and Indiana FarmersPinkuProtimGogoi100% (1)

- The Holy Grail of Curing DPDRDocument12 pagesThe Holy Grail of Curing DPDRDany Mojica100% (1)

- Hazard Full SlideDocument31 pagesHazard Full SlideRenKangWongNo ratings yet

- Project WorkPlan Budget Matrix ENROLMENT RATE SAMPLEDocument3 pagesProject WorkPlan Budget Matrix ENROLMENT RATE SAMPLEJon Graniada60% (5)

- Evaluation of Precision Performance of Quantitative Measurement Methods Approved Guideline-Second EditionDocument56 pagesEvaluation of Precision Performance of Quantitative Measurement Methods Approved Guideline-Second EditionHassab Saeed100% (1)

- 2008 Novus Sustainability ReportDocument28 pages2008 Novus Sustainability ReportNovusNo ratings yet

- 2009 Novus Sustainability ReportDocument81 pages2009 Novus Sustainability ReportNovusNo ratings yet

- The Egg's Global Footprint: Searching For True Sustainability in Global Egg ProductionDocument9 pagesThe Egg's Global Footprint: Searching For True Sustainability in Global Egg ProductionNovusNo ratings yet

- Methionine Global Outlook: The Next DecadeDocument25 pagesMethionine Global Outlook: The Next DecadeNovusNo ratings yet

- 80-Article Text-264-1-10-20200729Document6 pages80-Article Text-264-1-10-20200729ulfaNo ratings yet

- Reactive Orange 16Document3 pagesReactive Orange 16Chern YuanNo ratings yet

- Hahnemann Advance MethodDocument2 pagesHahnemann Advance MethodRehan AnisNo ratings yet

- Pre/Post Test in Mapeh 6 Name: - DateDocument5 pagesPre/Post Test in Mapeh 6 Name: - Datema. rosario yumangNo ratings yet

- Drug Study - CiprofloxacinDocument2 pagesDrug Study - CiprofloxacinryanNo ratings yet

- CementumDocument26 pagesCementumPrathik RaiNo ratings yet

- Supersize Me: An Exploratory Analysis of The Nutritional Content in Mcdonald's Menu ItemsDocument7 pagesSupersize Me: An Exploratory Analysis of The Nutritional Content in Mcdonald's Menu ItemsIjahss JournalNo ratings yet

- Certification of Psychology Specialists Application Form: Cover PageDocument3 pagesCertification of Psychology Specialists Application Form: Cover PageJona Mae MetroNo ratings yet

- Setons in The Treatment of Anal Fistula Review of Variations in Materials and Techniques 2012Document9 pagesSetons in The Treatment of Anal Fistula Review of Variations in Materials and Techniques 2012waldemar russellNo ratings yet

- Nurse Licensure Examination Review Center for Allied Professions (RCAPDocument15 pagesNurse Licensure Examination Review Center for Allied Professions (RCAPnikko0427No ratings yet

- DRRM Plan2020 2021Document5 pagesDRRM Plan2020 2021SheChanNo ratings yet

- Nursing Acn-IiDocument80 pagesNursing Acn-IiMunawar100% (6)

- Corn SpecDocument4 pagesCorn SpecJohanna MullerNo ratings yet

- Moosa Amandio PDFDocument12 pagesMoosa Amandio PDFMussa AmândioNo ratings yet

- Safety Data Sheet SummaryDocument8 pagesSafety Data Sheet SummaryReffi Allifyanto Rizki DharmawamNo ratings yet

- BSN 3G GRP 4 Research TitlesDocument6 pagesBSN 3G GRP 4 Research TitlesUjean Santos SagaralNo ratings yet

- EpididymitisDocument8 pagesEpididymitisShafira WidiaNo ratings yet

- BICEP GROWTHDocument3 pagesBICEP GROWTHJee MusaNo ratings yet

- CRS Report: Federal Employee Salaries and Gubernatorial SalariesDocument54 pagesCRS Report: Federal Employee Salaries and Gubernatorial SalariesChristopher DorobekNo ratings yet

- 2017EffectofConsumptionKemuningsLeafMurrayaPaniculataL JackInfusetoReduceBodyMassIndexWaistCircumferenceandPelvisCircumferenceonObesePatientsDocument5 pages2017EffectofConsumptionKemuningsLeafMurrayaPaniculataL JackInfusetoReduceBodyMassIndexWaistCircumferenceandPelvisCircumferenceonObesePatientsvidianka rembulanNo ratings yet

- hw410 Unit 9 Assignment Final ProjectDocument9 pageshw410 Unit 9 Assignment Final Projectapi-649875164No ratings yet

- Test Bank For Fundamental Nursing Skills and Concepts Tenth EditionDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Fundamental Nursing Skills and Concepts Tenth Editionooezoapunitory.xkgyo4100% (41)

- REAL in Nursing Journal (RNJ) : Penatalaksanaan Pasien Rheumatoid Arthritis Berbasis Evidence Based Nursing: Studi KasusDocument7 pagesREAL in Nursing Journal (RNJ) : Penatalaksanaan Pasien Rheumatoid Arthritis Berbasis Evidence Based Nursing: Studi Kasustia suhadaNo ratings yet

- Endocervical PolypDocument2 pagesEndocervical PolypRez007No ratings yet