Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Management of Agitation

Uploaded by

Mahmoud Ahmed MahmoudOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Management of Agitation

Uploaded by

Mahmoud Ahmed MahmoudCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction and Presentation

Management of Agitation

INTRODUCTION AND PRESENTATION

Though the ED is the safety net for society, it is not uncommon for ED personnel to be placed in harms way when helping an agitated or violent patient. All emergency medicine personnel need to be aware of the signs and symptoms of potential violence. Any patient can become violent, but patients with organic disorders such as dementia, delirium, and chemical intoxication have a higher incidence of violence, as do functional disorders such as mania and schizophrenia.

AVOIDING VIOLENCE

Many patients who become violent are fortunately not violent from the moment they come through the door. This allows the staff to prepare but it also allows for alternative measures to restraints to be employed. A doctrine called the least restrictive method of restraint should be employed when dealing with the potentially violent patient. This means that a patient should be provided alternatives to correct inappropriate behavior in order to maintain a good working doctor/patient relationship and to maintain the dignity of the patient. There are a number of important things to keep in mind in order to avoid escalating a potentially violent situation.

These methods of talking a patient down include:

1. Avoid eye contact with patient. 2. Do not block exits and leave the door to the exam room open. 3. Maintain a good distance from potentially violent patient; do not invade the patients space. 4. Adopt passive, non-confrontational posture and attitude, and allow patient to ventilate his feelings. Develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient. 5. Treat the patient as you expect him to behave. 6. Offer the patient food or drink. 7. Do not make challenging, provocative, or belligerent remarks. 8. If the patient acts out, tell the patient directly your behavior is frightening others and we cannot allow such behavior. 9. Do not turn your back on potentially violent patient.

Management of Agitation

The Decision to Use Restraints

10. Never underestimate the potential for violence. Lastly, if in spite of reasonable measures by ED staff, the patients conduct continues to escalate, the ED physician should try to enlist the help and influence of the patients family or friends. The use of family and friends can have a profound influence on a patients behavior; however, it needs to be understood by the helper that he/she is working with the staff to modify the patients behavior and not to escalate a potentially dangerous situation. The last thing the ED staff needs is to go from one potentially violent patient to two or more.

THE DECISION TO USE RESTRAINTS

Once the use of less restrictive methods of modifying the patients behavior, such as talking them down have failed then the use of restraints may become necessary. The doctrine of the least restrictive method of restraint applies here as well. Providing the patient with options for modifying his/her behavior allows a patient/doctor relationship to be maintained. A patient may choose one method of restraint over another (i.e. Agree to seclusion over physical restraints). If it is not possible to engage the patient, and have him/her participate in their treatment, and the situation presents a risk of injury to the patient or staff then it becomes necessary to use force to restrain the patient. This should be done with a team approach that is well rehearsed, in which all the participants understand their role. This can be done in the following manner: Placing 4-5 security officers in clear view of the patient, but 10-15 feet distant. The ED physician should then notify the patient in a firm, but not threatening voice, that the continuation of the patients uncontrolled and disruptive behavior will not be allowed, and that the patient will be restrained by the team unless he lies down now on the ED cart and cooperates with the medical staff.

METHODS OF RESTRAINTS

1. Seclusion:

The placing of a patient alone in a locked room from which he/she cannot leave is seclusion. It is considered a form of restraint and therefore needs to be monitored, usually by video surveillance, and the reason for seclusion documented in the same way as other restraints. This is often considered the least restrictive form of restraint but many emergency departments do not have the necessary room to allow for seclusion. The specific room in which a patient is secluded must be observable, devoid of any potentially harmful objects and meet the local health code for such rooms. If the patient does not respond to seclusion then physical restraints may be necessary.

Management of Agitation

Methods of Restraints

2. Physical restraints:

Physical restraints should be used if, in the ED physicians medical opinion, the patient is a danger to themselves, other patients or the staff. Also, the ED physician can use good faith restraints to allow evaluation and treatment of an uncooperative incompetent patient (such as a patient with dementia). If physical restraints are to be used, they should be used properly and restraints must be adequate. Use of physical restraints: 1. Team approach, ideally with six members, one for each extremity, one for head, and one to apply restraints. The team members should remove all objects from themselves which could be used as weapons by the violent patient, i.e., ID pins, reflex hammers, pagers, stethoscopes around neck of staff, etc. Team should advance as a unit from all directions, restraining their assigned extremity. Team members should wear protective gear, at least gloves, to minimize possible contamination of themselves. 2. Generally all violent patients need four limb restraints. 3. Explain to patient that the restraints are being applied for his protection and the protection of others, as he cannot seem to control his behavior. Do not negotiate. Emphasize the therapeutic reasons for the restraints, not the punitive. 4. Can apply soft cervical collar that may also restrict patients range of motion and minimize head banging and biting. 5. Patient should be kept in open area where he can be observed and monitored. Change position of restrained extremities often and check for neurovascular function. 6. Undress patient and search for concealed weapons or chemicals after the restraints are applied. 7. The ED physician must document fully the reasons the restraints were necessary. 8. Make the entire restraint procedure a team effort, like cardiac arrest resuscitation, with assigned functions.

3. Chemical restraints:

The order in which restraints are used does not need to be physical and then chemical. If the patient is willing to take medication prior to the use of physical restraints then give him/her the medication. Often patient just want to get back on their medications in order to feel better (stop the voices) and so will take medication with better cooperation than physical restraints. Chemical restraints can also be used after physical restraints if the patient continues to struggle against the restraints and shows a persistence of uncontrolled behavior.

Management of Agitation

Methods of Restraints

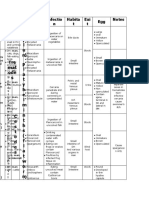

Gather as much history, physical exam, and laboratory information as possible after physical restraints and before chemical restraints, as medications may alter the patients behavior, rendering diagnosis difficult. Consider contacting the psychiatric consultant before chemically restraining the patient, as the consultant may wish to see and examine the patient before medications are used. Once the decision to use chemical restraints is made it becomes a question of what medications should be used. I. Lorazepam:

Until very recently, treatment options for agitation were limited to lorazepam and firstgeneration antipsychotics. Lorazepam, which has been in use for many years, leads to nonspecific sedation. Lorazepams main advantage, in contrast to the other benzodiazepines, is that it is reliably absorbed intramuscularly. Lorazepam has a relatively short half-life of 1020 hours, and has no active metabolites. The usual dose ranges from 0.52 mg, and can be administered every hour if necessary. It does not need to be administered intramuscularly; it can be given orally, sublingually, or intravenously. Lorazepam is advantageous in that it treats any underlying alcohol or sedative withdrawal. This is especially important in a patient with an unknown medical history. Symptoms of alcohol withdrawal can emerge after a patient is admitted to the hospital. To a doctor who is unaware of a patients alcohol dependency, the agitation that accompanies alcohol withdrawal can be interpreted as a symptom of some other syndrome. Use of lorazepam can assuage both the patients agitation and withdrawal. There are problems with lorazepam, however respiratory depression can occur in patients who are vulnerable to it, such as patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, patients who are obese, or patients with a history of sleep apnea. It may also cause disinhibition or paradoxical reactions, which seem to cause patients to get more agitated and even aggressive. This latter complication is seen more often in patients who have some degree of brain damage. Though it is relatively uncommon, physicians should be alert to its possibility. One drawback of using benzodiazepines such as lorazepam is that prolonged daily use is not optimal. Patients develop physiological tolerance and will require ever-increasing doses to achieve the same therapeutic effect. Lorazepam also has little to no effect on the core symptoms of psychosis.

Management of Agitation

Methods of Restraints II. First-Generation (Classic) Antipsychotics:

For decades, first-generation antipsychotics were the only alternative to lorazepam or barbiturates such as sodium amytal. Given a high enough dose, these agents universally cause sedation. Several intramuscular (IM) preparations are available. Clinicians can choose between the potency and sedating effects of agents. For example, chlorpromazine is a low potency/high sedating agent; haloperidol is a high potency/low sedating agent. In truth, both types can be used to quell agitation, but the risk of side effects varies with each. Hypotension, for example, is more commonly seen with chlorpromazine. Acute dystonia is more commonly expected with haloperidol. An advantage of using first-generation antipsychotics is that they will treat underlying positive symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions in a patient with schizophrenia. First-generation antipsychotics and lorazepam are often combined. A popular combination is haloperidol and lorazepam, which can be administered in the same syringe. There are advantages in speed of onset and tolerability of this combination, but long-term use is still problematic. In addition to the problems associated with the prolonged use of lorazepam discussed above, the long-term use of first-generation antipsychotics can lead to problems with extrapyramidal side effects (EPS), such as acute dystonia (frightening for the patient and can lead to lack of future treatment adherence) or akathisia (often confused for agitation with resultant additional injections of the agent that caused the akathisia). Droperidol, a neuroleptic approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use as a preanesthetic agent, is not approved to treat psychoses. Droperidol had been available in the United Kingdom, but was withdrawn from that market in 2001 because of the risk of QT interval prolongation. A black box warning was consequently placed on the US product label, and use of Droperidol in the United States has declined. However, it is still considered to be a good sedating agent by many emergency room physicians. Droperidol can be given intramuscularly or intravenously, and can lead to a rapid reduction in agitation. First-generation antipsychotics must be used with caution. As mentioned, these agents are associated with the occurrence of acute dystonic reactions and akathisia. If akathisia is mistaken for agitation, a clinician may decide to administer additional doses of first-generation antipsychotics, which will only compound the problem. Long-term exposure to first-generation antipsychotics has been associated with tardive dyskinesia. Additionally, a decrease in the seizure threshold can be seen with all first-generation antipsychotics, making patients who are withdrawing from alcohol or sedatives more prone to seizures.

Management of Agitation

Methods of Restraints III. Second-Generation (Atypical) Antipsychotics:

In the past several years atypical antipsychotics have become available. Classic antipsychotics block the D2 dopamine receptor. The atypical antipsychotics block the 5-HT2 serotonin receptor with relatively low D2 blockade. The blockade of this combination of receptors, particularly the higher ratio of 5-HT2 to D2 blockade, is believed to be responsible for the low incidence of EPS seen with these medications. A number of medications fall into this category; clozapine (Clozaril), olanzapine (Zyprexa), quetiapine (Seroquel), risperidone (Risperdal), and Ziprasidone (Geodon). o Clozapine: is not used because at the doses needed to effect an immediate change in behavior there is a risk of serious side effects such as seizures and agranulocytosis. In addition, quetiapine is not used because it carries a recommendation of slow titration and so cannot be used at the doses needed to change behavior abruptly. o Olanzapine: has a potentially beneficial sedating effect because it has 160 times the antihistamine potency of diphenhydramine but it has been associated with weight gain and the development of diabetes mellitus. o Risperidone: has been found to be equivalent to haloperidol in the treatment of psychosis and may be more effective than haloperidol in treating aggression. In a comparison of oral risperidone (in combination with oral lorazepam) with IM haloperidol (in combination with IM lorazepam) the two drug combinations were found to be equivalent both in overall efficacy and onset of action. The mean time to sleep was 43 minutes in the risperidone group and 44 minutes in the haloperidol group. Risperidone comes in both a liquid and dissolving tablet formulation. This can be important if you are worried about the patient cheeking the medication and thus noncompliance. When trying to maintain some autonomy for the acutely agitated patient it is convenient to be able to offer him/her a choice of oral or IM medication. Oral is often preferred if the patient is willing to take the medication. However, in the ED the ability to give medication via the intramuscular route is often necessary for the treatment of the acutely agitated patient who is unwilling to take oral medication.

Management of Agitation

Legality of Restraints o Ziprasidone: is currently the only IM atypical antipsychotic on the market, though Olanzapine is being studied. Ziprasidone has been studied in agitated psychotic patients and was found to be effective at dosage range of 10 to 20 mg. In addition, when comparing haloperidol and Ziprasidone in the treatment of acute psychosis, it was found that Ziprasidone was significantly more effective at reducing the symptoms of psychosis as measured on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). It was also found that there were significantly less movement disorder side effects with Ziprasidone. Taken together the atypical antipsychotics have a decreased incidence of prolonged QT when compared to the classic antipsychotics though this has been shown to be dose related and to vary between the medications with olanzapine having the smallest change in QT interval and Ziprasidone having the largest. EPS is also decreased in the atypical group compared to the classic antipsychotics. As mentioned above this is believed to be related to the ratio of 5-HT2 to D2 receptor blockade. This ratio may explain why clozapine has very few EPS and risperidone is intermediate between clozapine and classic antipsychotics.

LEGALITY OF RESTRAINTS

The decision to place a patient in restraints is often complicated, and sometimes anxiety provoking, for EM physicians. There are three things that need to be considered when deciding about the use of restraints in any given situation. First, is the patient competent to make decisions about his/her health care? Competency is defined as the capacity or ability to understand the nature and effects of ones actions or decisions. Patients are presumed competent until it is determined by actions or expressed thoughts that they are not. In general, the law implies consent during an emergency. However, it is important to note that though in the ED a patient does have the right to refuse certain options in their treatment. The second condition is the duty to protect the patient and other ED staff. As noted in the introduction, violence occurs frequently in the ED and thus protection of the staff as well as the patient is necessary. The last condition is the protection of third parties. It has been upheld in the courts that physicians, due to their unique relationship with patients, must bear the responsibility of protecting people to whom the patient threatens to do harm. In other words, if a patient is threatening to kill someone it is the responsibility of the physician to either detain that patient for medical or legal evaluation, or notify the third party of the threat.

Management of Agitation

References:

REFERENCES:

o o o o o Science-based treatment of aggression and agitation. Treatment of Violent Behavior. In: Tasman A, Lieberman J, Kay J, eds. Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Atypical antipsychotics for acute agitation. First Aid for the Psychiatry Boards. Gelder -Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry.

Management of Agitation

You might also like

- Module 2 Mental HealthDocument8 pagesModule 2 Mental HealthViolet CrimsonNo ratings yet

- RestrainingDocument9 pagesRestrainingRavi PaulNo ratings yet

- Aggressive Behaviors - ExtendedDocument7 pagesAggressive Behaviors - ExtendedTeresa SilvaNo ratings yet

- AgressionDocument35 pagesAgressionnamah odatNo ratings yet

- Pharmacological Behaviour Management (Quite Fine) (Nellore)Document82 pagesPharmacological Behaviour Management (Quite Fine) (Nellore)ultraswamy50% (2)

- Physical and Chemical Restraints in the EDDocument13 pagesPhysical and Chemical Restraints in the EDwatsjoldNo ratings yet

- Agitacion Aguda PDFDocument9 pagesAgitacion Aguda PDFMaría José Díaz RojasNo ratings yet

- NCP For SchizoDocument5 pagesNCP For SchizoRichelene Mae Canja100% (2)

- Psychiatric Emergencies 2Document27 pagesPsychiatric Emergencies 2Lulano MbasuNo ratings yet

- Unit 7 Therapies Used in PsychiatryDocument26 pagesUnit 7 Therapies Used in PsychiatryIsha BhusalNo ratings yet

- Guillain Barre SyndromeDocument21 pagesGuillain Barre Syndromebasinang_jangilNo ratings yet

- CMS Standards Regarding The Use of Restraints and SeclusionDocument4 pagesCMS Standards Regarding The Use of Restraints and Seclusionapi-299934163No ratings yet

- Order IDDocument8 pagesOrder IDJames NdiranguNo ratings yet

- DocxDocument7 pagesDocxShannon GarciaNo ratings yet

- NaharDocument42 pagesNahargrace0122rnNo ratings yet

- Conscious Sedation:: It Shouldn't Be A Bad Memory!Document68 pagesConscious Sedation:: It Shouldn't Be A Bad Memory!Saroj DeoNo ratings yet

- Nursing InductionDocument114 pagesNursing InductionMichael Long92% (26)

- IM Communication Skills Teaching-Sem 8Document13 pagesIM Communication Skills Teaching-Sem 8Cynthia SooNo ratings yet

- Ant11 ED Mental Health 1030 1Document3 pagesAnt11 ED Mental Health 1030 1fau fauNo ratings yet

- Fall Prevention: How Can Older Adults Prevent Falls?Document4 pagesFall Prevention: How Can Older Adults Prevent Falls?Amalina ZahariNo ratings yet

- Acute Agitation PDFDocument12 pagesAcute Agitation PDFRamin ZojajiNo ratings yet

- Anxiety: Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment (Behavioral Health) - CEDocument7 pagesAnxiety: Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment (Behavioral Health) - CEircomfarNo ratings yet

- Communication SkillsDocument5 pagesCommunication SkillssanthoshNo ratings yet

- Seclusion and Physical Restraint: GeneralDocument6 pagesSeclusion and Physical Restraint: GeneralMegan ClearyNo ratings yet

- Care of Client in Acute Biologic CrisisDocument16 pagesCare of Client in Acute Biologic CrisisMerlene Sarmiento SalungaNo ratings yet

- Emergency Physician Guide to Preventing ViolenceDocument2 pagesEmergency Physician Guide to Preventing ViolenceMiyo Tan100% (1)

- Evaluation of Interventions for R.LDocument8 pagesEvaluation of Interventions for R.LLindsay Grace MandarioNo ratings yet

- Principles of Nursing 1st CompressedDocument45 pagesPrinciples of Nursing 1st Compressedlovi.ortiz.auNo ratings yet

- Emergency Psychiatry: Christos Dagadakis, MD, MPHDocument40 pagesEmergency Psychiatry: Christos Dagadakis, MD, MPHNaveen EldoseNo ratings yet

- Sedation and Paralysis in The MICUDocument17 pagesSedation and Paralysis in The MICUMark Hammerschmidt100% (6)

- Seizures & Teens: When Emergencies Happen, What To Do?Document4 pagesSeizures & Teens: When Emergencies Happen, What To Do?Muhammad Ilyas ChannaNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument7 pagesCase StudyAaron WallaceNo ratings yet

- MGT Aggression-Mr MuluDocument5 pagesMGT Aggression-Mr MuluE- TutorNo ratings yet

- S E L F - P E R C E P T I O N - S E L F - C O N C E P T P A T T E R A. 1Document4 pagesS E L F - P E R C E P T I O N - S E L F - C O N C E P T P A T T E R A. 1Diana TardecillaNo ratings yet

- Agitated & Combative Patients: Sample Medical GuidelinesDocument2 pagesAgitated & Combative Patients: Sample Medical GuidelinesKathzkaMaeAgcaoiliNo ratings yet

- Administration of Psychotropic DrugsDocument22 pagesAdministration of Psychotropic DrugsdhivyaramNo ratings yet

- A Modern Day Fight Club? New2017Document14 pagesA Modern Day Fight Club? New2017Deanne Morris-DeveauxNo ratings yet

- Common Nursing Errors and Documentation MistakesDocument59 pagesCommon Nursing Errors and Documentation MistakesCzerwin JualesNo ratings yet

- Anxiety Control and SedationDocument44 pagesAnxiety Control and SedationهجرسNo ratings yet

- Psych HESI Hints: Members For The Client's Safety (E.g., Suicide Plan) and Optimal TherapyDocument7 pagesPsych HESI Hints: Members For The Client's Safety (E.g., Suicide Plan) and Optimal TherapyChristina100% (10)

- Patient CounsellingDocument46 pagesPatient CounsellingKeith OmwoyoNo ratings yet

- Restraining Procedure: General Principles For Use of RestraintsDocument10 pagesRestraining Procedure: General Principles For Use of RestraintsHardeep KaurNo ratings yet

- Care of Patient in Acute Biologic CrisisDocument58 pagesCare of Patient in Acute Biologic CrisisVon LarenaNo ratings yet

- Restraint Use and Patient Care: Nnual CompetencyDocument35 pagesRestraint Use and Patient Care: Nnual CompetencyrustiejadeNo ratings yet

- The Use of Restraints and Psychotropic Medications in People With DementiaDocument36 pagesThe Use of Restraints and Psychotropic Medications in People With DementiaSBS_NewsNo ratings yet

- Medical AdherenceDocument12 pagesMedical AdherenceCristine Loh100% (2)

- Module 3 - Responding EffectivelyDocument2 pagesModule 3 - Responding EffectivelyjessafesalazarNo ratings yet

- Implement and Monitor Infection Control Policies and Procedure in CaregivingDocument91 pagesImplement and Monitor Infection Control Policies and Procedure in Caregivingjessica coronelNo ratings yet

- KETOROLACDocument7 pagesKETOROLACtalitha kumiNo ratings yet

- Three categories of restraints and proper body mechanicsDocument7 pagesThree categories of restraints and proper body mechanicsgireeshsachinNo ratings yet

- Patient Counselling - CPDocument8 pagesPatient Counselling - CPmrcopy xeroxNo ratings yet

- Health Teaching On Ta - HbsoDocument3 pagesHealth Teaching On Ta - Hbsomecz26No ratings yet

- Nursing Induction PPT 2Document114 pagesNursing Induction PPT 2Mukesh Choudhary Jat100% (3)

- Hesi Psych Study GuideDocument16 pagesHesi Psych Study GuideR100% (17)

- Medical Ward - Discharge PlanDocument5 pagesMedical Ward - Discharge Plandon7dane100% (1)

- Anti-Aging Therapeutics Volume XIIIFrom EverandAnti-Aging Therapeutics Volume XIIINo ratings yet

- Restraints in Dementia Care: A Nurse’s Guide to Minimizing Their UseFrom EverandRestraints in Dementia Care: A Nurse’s Guide to Minimizing Their UseNo ratings yet

- The Slim Book of Health Pearls: The Prevention of Medical ErrorsFrom EverandThe Slim Book of Health Pearls: The Prevention of Medical ErrorsNo ratings yet

- What Happens During Drug Rehab? The Information You Need to Help Yourself or Someone You LoveFrom EverandWhat Happens During Drug Rehab? The Information You Need to Help Yourself or Someone You LoveNo ratings yet

- Anti-Microbial Therapy Final With AlarmsDocument245 pagesAnti-Microbial Therapy Final With AlarmsMahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Ovarian Hyperstimulation SyndromeDocument3 pagesOvarian Hyperstimulation SyndromeMahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Fetal Malnutrition: DR. Mahmoud Ahmed Mahmoud Ahmed Faculty of Medicine Alexandria UniversityDocument11 pagesFetal Malnutrition: DR. Mahmoud Ahmed Mahmoud Ahmed Faculty of Medicine Alexandria UniversityMahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Non-Ischemic Central Retinal Vein OcclusionDocument17 pagesNon-Ischemic Central Retinal Vein OcclusionMahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion (BRVO)Document4 pagesBranch Retinal Vein Occlusion (BRVO)Mahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Fetal MalnutritionDocument2 pagesFetal MalnutritionMahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Investigative HepatologyDocument24 pagesInvestigative HepatologyMahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Non-Ischemic Central Retinal Vein OcclusionDocument6 pagesNon-Ischemic Central Retinal Vein OcclusionMahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Investigative HepatologyDocument6 pagesInvestigative HepatologyMahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Livor MortisDocument16 pagesLivor MortisMahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Drug Management of AgitationDocument14 pagesDrug Management of AgitationMahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Livor MortisDocument5 pagesLivor MortisMahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Surgery For Cancer LarynxDocument13 pagesEndoscopic Surgery For Cancer LarynxMahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Iphtheria Accine Oxoid: Mahmoud Ahmed Mahmoud 846Document23 pagesIphtheria Accine Oxoid: Mahmoud Ahmed Mahmoud 846Mahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Diphtheria VaccineDocument5 pagesDiphtheria VaccineMahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Phylum Platyhelminths (Flat Worms)Document2 pagesPhylum Platyhelminths (Flat Worms)Mahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Surgery For Cancer LarynxDocument11 pagesEndoscopic Surgery For Cancer LarynxMahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- A-Autonomic Drugs: 1) CholinergicDocument28 pagesA-Autonomic Drugs: 1) CholinergicMahmoud Ahmed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Drug Book - 1Document204 pagesPsychiatric Drug Book - 1Anushri ManeNo ratings yet

- Genetic Causes of Schizophrenia: Methamphetamine MarijuanaDocument5 pagesGenetic Causes of Schizophrenia: Methamphetamine MarijuanaAzam RehmanNo ratings yet

- SchizophreniaDocument22 pagesSchizophreniaalfauzi syamsudinNo ratings yet

- Antipsychotic Drugs Grandiosity Hallucinations Paranoia DelusionsDocument63 pagesAntipsychotic Drugs Grandiosity Hallucinations Paranoia DelusionsMuhammad Masoom Akhtar100% (1)

- SchizophreniaDocument7 pagesSchizophreniaMANOJ KUMARNo ratings yet

- Extrapyramidal Symptoms Guide: Dystonia, Akathisia, Parkinsonism & Tardive DyskinesiaDocument35 pagesExtrapyramidal Symptoms Guide: Dystonia, Akathisia, Parkinsonism & Tardive DyskinesiaLucas PhiNo ratings yet

- Anti Psychotic DrugsDocument6 pagesAnti Psychotic DrugsJoseph NyirongoNo ratings yet

- Module 1 - IntroductionDocument30 pagesModule 1 - Introductionpsychopharmacology100% (2)

- Basic Pharmacology of Antipsychotic AgentsDocument29 pagesBasic Pharmacology of Antipsychotic AgentsZane PhillipNo ratings yet

- Injection SOP 2011 (3rd Edition)Document70 pagesInjection SOP 2011 (3rd Edition)lynlgsxrNo ratings yet

- Beyond Schizophrenia Living and Working With A Serious Mental IllnessDocument251 pagesBeyond Schizophrenia Living and Working With A Serious Mental Illnessdrago66No ratings yet

- 1.schizophrenia An Overview PDFDocument5 pages1.schizophrenia An Overview PDFNadyaNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Guide EN PDFDocument79 pagesSchizophrenia Guide EN PDFMichaelus1No ratings yet

- Perspectives in Pharmacology: Roger D. Porsolt, Vincent Castagné, Eric Hayes, and David VirleyDocument5 pagesPerspectives in Pharmacology: Roger D. Porsolt, Vincent Castagné, Eric Hayes, and David Virleyel egendNo ratings yet

- Antipsychotic DrugsDocument34 pagesAntipsychotic DrugsvimalaNo ratings yet

- Antipsychotic Drugs For Elderly PatientsDocument11 pagesAntipsychotic Drugs For Elderly Patientsneutron mobile gamingNo ratings yet

- Biological Treatments in PsychiatryDocument56 pagesBiological Treatments in PsychiatryNurul AfzaNo ratings yet

- GNC Psy Nursing QuestionsDocument34 pagesGNC Psy Nursing QuestionsFan Eli100% (1)

- Schizophrenia and Related Disorder: by Dr. Noor AbdulamirDocument36 pagesSchizophrenia and Related Disorder: by Dr. Noor Abdulamirاحمد الهاشميNo ratings yet

- Seminar on Childhood SchizophreniaDocument29 pagesSeminar on Childhood SchizophreniaRIYA MARIYATNo ratings yet

- Neuroleptics & AnxiolyticsDocument65 pagesNeuroleptics & AnxiolyticsAntonPurpurovNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Diagnosis, Symptoms & Treatment /TITLEDocument50 pagesSchizophrenia Diagnosis, Symptoms & Treatment /TITLEelvinegunawanNo ratings yet

- PimozideDocument5 pagesPimozideMega AnandaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Psychosis and SchizophreniaDocument32 pagesUnderstanding Psychosis and SchizophreniaAnonymous zxTFUoqzklNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Week 4, Cognition Performance Exit Final ScoreDocument100 pagesMental Health Week 4, Cognition Performance Exit Final ScoreNadia LoveNo ratings yet

- Overview of Psychotropic DrugsDocument7 pagesOverview of Psychotropic Drugsnad101No ratings yet

- Comprehensive Neurology Board Review-THIRD EDITIONDocument44 pagesComprehensive Neurology Board Review-THIRD EDITIONDr. Chaim B. Colen50% (4)

- Understanding the Types and Symptoms of SchizophreniaDocument18 pagesUnderstanding the Types and Symptoms of SchizophreniaAaron WallaceNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Psychology 2nd Edition Nolen-Hoeksema Test Bank 1Document52 pagesAbnormal Psychology 2nd Edition Nolen-Hoeksema Test Bank 1jamie100% (30)