Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Strongyloides

Uploaded by

Arvindan SubramaniamCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Strongyloides

Uploaded by

Arvindan SubramaniamCopyright:

Available Formats

Strongyloides

Morning Report

Dec 14

th

, 2009

Nicole Cullen

What is Strongyloides?

Parasitic infection

with a predilection for the

intestines

2 most common and clinically

relevant species are:

Strongyloides stercoralis

Strongyloides fuelleborni

Limited to Africa and Papua New

Guinea

Epidemiology

Relatively uncommon in the US

BUT, endemic areas in the rural parts of the

Southeastern states and the Appalachian

mountain area

Certain pockets with prevalence 4%

Usually found in tropical and subtropical

countries

Prevalence up to 40% in areas of West Africa, the

Caribbean, Southeast Asia

Affects >100 million worldwide

No sexual or racial disparities. All age groups.

How Do You Get It?

Penetration of intact skin by filiariform

larvae in the soil, or ingestion through

contaminated food or water

Larvae enter the circulation

Lungs alveoli ascension up

tracheobronchial tree swallowed molt

in the small bowel and mature into adult

female

Females enter the intestinal mucosa

and produce several eggs daily through

parthenogenesis (hatch during transit

through the gut)

Clinical Presentation

Acute infection:

Lower extremity itching (mild

erythematous maculopapular rash at

the site of skin penetration)

Cough, dyspnea, wheezing

Low-grade fevers

Epigastric discomfort, n/v/d

Clinical Presentation

Chronic Infection

Can be completely asymptomatic

Abdominal pain that can be very vague, crampy,

burning

Often worse after eating

Intermittent diarrhea

Can alternate with constipation

Occasional n/v

Weight loss (if heavy infestation)

Larva currens (racing larva a recurrent

maculopapular or serpiginous rash)

Usually begins perianally and extends up the buttocks,

upper thighs, abdomen

Chronic urticaria

Larva Currens

Clinical Presentation

Severe infection

Can be abrupt or insidious in onset

N/v/d, severe abdominal pain, distention

Cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea, wheezing, crackles

Stiff neck, headache, MS changes

If CNS involved

Fever/chills

Hematemesis, hematochezia

Rash (petechiae, purpura) over the trunk and proximal extremities

Caused by dermal blood vessel disruption brought on by massive

migration of larvae within the skin

Risk factors for severe infection

Immunosuppressant meds (steroids, chemo, TNF modulators,

tacro, etc all BUT cyclosporine)

Malignancy

Malabsorptive state

ESRD

DM

Advanced age

HIV

HTLV1

Etoh

Clinical Presentation

Can replicate in the host for

decades with minimal or no sx

High morbidity and mortality when

progresses to hyperinfection

syndrome or disseminated

strongyloidiasis

Usually in immunocompromised

hosts (pregnancy?)

Dangerous Complications

Hyperinfection Syndrome

Acceleration of the normal life cycle, causing

excessive worm burden

Autoinfection (turn into infective filariform larva within

the lumen

Spread of larvae outside the usual migration pattern

of GI tract and lungs

Disseminated strongyloidiasis

Widespread dissemination of larvae to extraintestinal

organs

CNS (meningitis), heart, urinary tract, bacteremia, etc

Can be complicated by translocation of enteric

bacteria

Travel on the larvae themselves or via intestinal ulcers

Mortality rate close to 80%

Due to delayed diagnosis, immunocompromised state

of the host at this point

Laboratory Findings

CBC

WBC usually wnl for acute and

chronic cases, can be elevated in

severe cases

Eosinophilia common during acute

infection, +/- in chronic infection

(75%), usually absent in severe

infection

Diagnostic Testing

Stool O&P

Microscopic ID of S. sterocoralis larvae is

the definitive diagnosis

Ova usually not seen (only helminth to

secrete larva in the feces)

Stool wet mount (direct exam)

In chronic infection, sensitivity only 30%,

can increase to 75% if 3 consecutive stool

exams

Can enhance larvae recovery with more

obscure methods (Baermann funnel, agar

plate, Harada-Mori filter paper)

Wet Mount

Larva seen via direct examination of stool

Serology

ELISA

Most sensitive method (88-95%)

May be lower in immunocompromised

patients

Cannot distinguish between past and

present infections

Can cross-react with other nematode

infections

If results are positive, can move on to

try and establish a microscopic dx

Imaging

CXR patchy alveolar infiltrates, diffuse

interstitial infiltrates, pleural effusions

AXR Loops of dilated small bowel,

ileus

Barium swallow stenosis, ulceration,

bowel dilitation

Small bowel follow-through worms in

the instestine

CT abdomen/pelvis nonspecific

thickening of the bowel wall

Procedures

EGD duodenitis, edematous mucosa, white

villi, erythema

Colonoscopy colitis

Duodenal aspiration examine for larvae

Sputum sample, bronchial washings, BAL

show larvae

Sputum cx

Nl respiratory flora organisms pushed to the outside

in groups as a result of migrating larvae

Characteristic pattern can be diagnostic of

S.Stercoralis infection

If CNS involved, LP gram stain, cell count/diff

( protein, glu, poly predominance), wet

mount prep

Histology

Larvae typically found in proximal

portion of small intestine

Embedded in lamina propria

Cause edema, cellular infiltration,

villous atrophy, ulcerations

In-long standing infections, may

see fibrosis

Treatment

Antihelminitic therapy

Ivermectin

Albendazole

Thiabendazole

Abx directed toward enteric pathogens if

bacteremia or meningitis (2-4wks)

Minimize immunosuppression as possible

Directed supportive tx

Transfusions if GI bleed, antihistamines for itching,

surgery if bowel perf, etc

Repeat course of antihelminitic therapy if

immunocompromised, as relapse common

Follow-Up

Repeat stool exams or duodenal

aspirations in 2-3 mos to document cure

Repeat serologies 4-8 mos after therapy

Ab titer should be low or undetectable 6-18

mos after successful tx

If titer not falling, additional

antihelminitic tx

Precautions for travelers to endemic

areas, but no prophylaxis or vaccine

available

References

Arch EL, Schaefer JT and Dahiya A. Cutaneous

manifestation of disseminated strongyloidiasis in a

patient coinfected with HTLV-1. Dermatology Online

Journal. 2008;14(12):6.

Chadrasekar PH, Bharadwaj RA, Polenakovik H,

Polenakovik S. Emedicine: Strongyloidiasis. April 3,

2009.

Concha R, Harrington W and Rogers A. Intestinal

Strongyloidiasis. Recognition, Management and

Determinants of Outcome. Journal of Clinical

Gastroengerology. 2005;39(3):203-211.

Greiner K, Bettencourt J, and Semolic C.

Strongyloidiasis: A Review and Update by Case

Example. Clinical Laboratory Science. 2008;21(2):82-8.

Siddiqui AA, Berk SL. Diagnosis of Strongyloides

stercoralis infection. Clin Infect Dis. October 1,

2001;33:1040-7.

Zeph, Bill. Strongyloides stercoralis Infection Can Be

Fatal. American Family Physician. March 15, 2002.

You might also like

- The 12 Month Blueprint JournalDocument117 pagesThe 12 Month Blueprint JournalMonmon100% (10)

- JOB SAFETY ANALYSISDocument21 pagesJOB SAFETY ANALYSISThái Đạo Phạm Lê100% (1)

- Dysphagia, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandDysphagia, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Treatment And Related ConditionsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- URINARY TRACT INFECTION - FinalDocument86 pagesURINARY TRACT INFECTION - FinalShreyance Parakh100% (2)

- Urinary Tract InfectionDocument9 pagesUrinary Tract InfectionTom Mallinson100% (1)

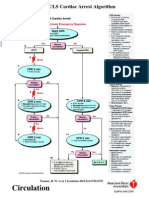

- ACLS Class Packet PDFDocument9 pagesACLS Class Packet PDFImam GultomNo ratings yet

- Pead 3 - Abdominal Pain and VommitingDocument22 pagesPead 3 - Abdominal Pain and Vommitingbbyes100% (1)

- DCS - THE BENDSDocument4 pagesDCS - THE BENDSArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Acute Abdomen: - DefinitionDocument27 pagesAcute Abdomen: - DefinitionWorku KifleNo ratings yet

- Junior Intern Review - Oral Revalida 2016Document170 pagesJunior Intern Review - Oral Revalida 2016Cyrus ZalameaNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Olds Maternal Newborn Nursing and Womens Health Across The Lifespan 8th Edition DavidsonDocument5 pagesTest Bank For Olds Maternal Newborn Nursing and Womens Health Across The Lifespan 8th Edition DavidsonJohnny Shields100% (25)

- NematodesDocument110 pagesNematodesRussel Bob BorromeoNo ratings yet

- Amebiasis, Giradiasis, Helminths: DR Asim ShresthaDocument49 pagesAmebiasis, Giradiasis, Helminths: DR Asim ShresthaAsim ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Dan Kiley - The Peter Pan Syndrome-Men Who Have Never Grown Up (PDF)Document291 pagesDan Kiley - The Peter Pan Syndrome-Men Who Have Never Grown Up (PDF)waytee85% (26)

- CKD Stages and ManagementDocument23 pagesCKD Stages and ManagementArvindan Subramaniam100% (1)

- CKD Stages and ManagementDocument23 pagesCKD Stages and ManagementArvindan Subramaniam100% (1)

- Physiological vaginal discharge and differential diagnosis of vaginal infectionsDocument52 pagesPhysiological vaginal discharge and differential diagnosis of vaginal infectionsArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- UTI in PregnancyDocument33 pagesUTI in Pregnancyyusufkiduchu8No ratings yet

- Cholangitis: Reported By: R. DongaranDocument18 pagesCholangitis: Reported By: R. DongaranVishnu Karunakaran100% (1)

- Bacterial Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs): Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentDocument27 pagesBacterial Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs): Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentNaseem Bin Yoosaf100% (1)

- Adominal TBDocument50 pagesAdominal TBTamjid KhanNo ratings yet

- Case Presentation VolvulusDocument34 pagesCase Presentation Volvulusanjawi5No ratings yet

- Juvenile CataractDocument44 pagesJuvenile CataractArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Communicable DiseasesDocument162 pagesCommunicable DiseasesCarlo VigoNo ratings yet

- +ascariasisDocument16 pages+ascariasisDr. SAMNo ratings yet

- Typhoid LectureDocument29 pagesTyphoid Lectureprofarmah6150No ratings yet

- Gastro NephroDocument93 pagesGastro Nephrohasanatiya41No ratings yet

- Paediatric UTIDocument24 pagesPaediatric UTIIlobun Faithful IziengbeNo ratings yet

- Urinary Tract InfectionsDocument21 pagesUrinary Tract InfectionsIlobun Faithful IziengbeNo ratings yet

- Gastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary Congenital MalformationsDocument43 pagesGastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary Congenital MalformationshusnaaNo ratings yet

- 3) Typhoid FeverDocument36 pages3) Typhoid FeversmrutuNo ratings yet

- Post-Weaning Multisystemic Wasting Syndrome: Circo Virus Type 2 Infection ?!Document12 pagesPost-Weaning Multisystemic Wasting Syndrome: Circo Virus Type 2 Infection ?!andreisandorNo ratings yet

- Surgery Posting 1: Adewumi Toluwalope .EDocument20 pagesSurgery Posting 1: Adewumi Toluwalope .EAdewumi ToluNo ratings yet

- Viral Gastroenteritis: Submitted byDocument20 pagesViral Gastroenteritis: Submitted byRavi PrakashNo ratings yet

- Group 12 Case 2bDocument52 pagesGroup 12 Case 2bDaniel Hans JayaNo ratings yet

- Amoebiasis Causes and SymptomsDocument59 pagesAmoebiasis Causes and SymptomsSaurabh AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Urinary Tract InfectionDocument31 pagesUrinary Tract InfectionAof VongsumranNo ratings yet

- Case 2B (Group 8) Blok GITDocument74 pagesCase 2B (Group 8) Blok GITkheluwisNo ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis Diagnosis and Treatment GuideDocument109 pagesAcute Appendicitis Diagnosis and Treatment GuideHadi SalehNo ratings yet

- Enteric (Typhoid) FeverDocument24 pagesEnteric (Typhoid) FeverDr venkatesh jalluNo ratings yet

- Dysphagia: Dr. Sangeeta Aggarwal Assistant Professor, E.N.T Deptt GMCH, PatialaDocument29 pagesDysphagia: Dr. Sangeeta Aggarwal Assistant Professor, E.N.T Deptt GMCH, PatialaVishalNo ratings yet

- Amoebiasis: (Amoebic Dysentery)Document32 pagesAmoebiasis: (Amoebic Dysentery)abhinay_1712No ratings yet

- Liver FluksDocument28 pagesLiver Flukszaid nabeelNo ratings yet

- Round WormDocument11 pagesRound WormS GNo ratings yet

- Vdocuments - MX - Intestinal Parasites Helminths Cestodes Protozoa Intestinal Parasites HelminthsDocument55 pagesVdocuments - MX - Intestinal Parasites Helminths Cestodes Protozoa Intestinal Parasites HelminthsrgumralNo ratings yet

- First Problem: Erwin Budi/405130151Document42 pagesFirst Problem: Erwin Budi/405130151Rilianda SimbolonNo ratings yet

- Acute If 4 Weeks in DurationDocument9 pagesAcute If 4 Weeks in DurationSalsabila Rahma FadlillahNo ratings yet

- Canine Parvovirus Infection-2Document51 pagesCanine Parvovirus Infection-2irfanNo ratings yet

- NCMB 316 Cu11 Liver, Pancreas, & GallbladderDocument74 pagesNCMB 316 Cu11 Liver, Pancreas, & GallbladderJanine Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- GIS-K-25 Acute Appendicitis Appendiceal Mass / AbscessDocument24 pagesGIS-K-25 Acute Appendicitis Appendiceal Mass / AbscessYasmine Fitrina SiregarNo ratings yet

- Renal and Urological Disorders: A Concise GuideDocument30 pagesRenal and Urological Disorders: A Concise GuideIrma HermaliaNo ratings yet

- Based on the information provided, the most likely causative organism is Cytomegalovirus (CMV). CMV is a common opportunistic infection in HIV/AIDS patients that can cause esophageal ulcersDocument37 pagesBased on the information provided, the most likely causative organism is Cytomegalovirus (CMV). CMV is a common opportunistic infection in HIV/AIDS patients that can cause esophageal ulcersDanielle FosterNo ratings yet

- Galea - Abdominal Pain in ChildhoodDocument30 pagesGalea - Abdominal Pain in Childhoodsanty anggroiniNo ratings yet

- Urinary Tract Infections: Causes, Risk Factors and Diagnosis (39Document4 pagesUrinary Tract Infections: Causes, Risk Factors and Diagnosis (39oxford_commaNo ratings yet

- Viral Diseases of Alimentary Canal in CaninesDocument11 pagesViral Diseases of Alimentary Canal in CaninesNavneet BajwaNo ratings yet

- Uti 1Document75 pagesUti 1Muwanga faizoNo ratings yet

- Urinary Tract Infections: Dr. Shweta Naik Assistant ProfessorDocument62 pagesUrinary Tract Infections: Dr. Shweta Naik Assistant ProfessorMeenakshisundaram CNo ratings yet

- Articulo Abdomen AgudoDocument12 pagesArticulo Abdomen AgudoAlejandra VelezNo ratings yet

- Typhoid Fever: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument5 pagesTyphoid Fever: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and TreatmentElvisNo ratings yet

- Gavin Gamayo - Intestinal NematodesDocument50 pagesGavin Gamayo - Intestinal Nematodesgavin gamayoNo ratings yet

- Pyloric Stenosis: Supervisor: DR NTAGANDA Edmond, Consultant Ped SurgDocument21 pagesPyloric Stenosis: Supervisor: DR NTAGANDA Edmond, Consultant Ped SurgJames NTEGEREJIMANANo ratings yet

- Salmonellosis LectureDocument19 pagesSalmonellosis LectureEslam HamadaNo ratings yet

- Septriawan-Pemicu 4 B GITDocument79 pagesSeptriawan-Pemicu 4 B GITRanto B. TampubolonNo ratings yet

- Lung FlukesDocument23 pagesLung FlukesGelli LebinNo ratings yet

- Ascariasis & GiardiasisDocument34 pagesAscariasis & GiardiasisMuhammad ShahzadNo ratings yet

- Problem 4 GIT Kelompok 16Document90 pagesProblem 4 GIT Kelompok 16Andreas AdiwinataNo ratings yet

- K1. Elektif ParasitDocument34 pagesK1. Elektif ParasitUu'ayu UnyuNo ratings yet

- DR Anil Sabharwal MDDocument57 pagesDR Anil Sabharwal MDsaump3No ratings yet

- Salmonella Infections: (Salmonelloses)Document56 pagesSalmonella Infections: (Salmonelloses)andualemNo ratings yet

- Congenital Anomaly of Digestive SystemDocument26 pagesCongenital Anomaly of Digestive SystemTri PutraNo ratings yet

- Pap SmearDocument22 pagesPap SmearArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- The Male Genital System: Sri WiryawanDocument52 pagesThe Male Genital System: Sri WiryawanArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- NITALFUNCTIONDocument49 pagesNITALFUNCTIONArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- DIALISIS BacaDocument4 pagesDIALISIS BacabrokentinjaNo ratings yet

- Muscle RelaxanDocument14 pagesMuscle RelaxanArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approach in Kidney DiseasesDocument17 pagesDiagnostic and Therapeutic Approach in Kidney DiseasesKaliammah KumarNo ratings yet

- Siano SisDocument4 pagesSiano SisArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Leaflet CADocument1 pageLeaflet CAArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Hipertensi BacaDocument12 pagesHipertensi BacaArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Hipertensi BacaDocument12 pagesHipertensi BacaArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Tabla Peso TallaDocument10 pagesTabla Peso TallalamourpretoNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading Managing BPSD Treating Agitation and Aggression in The Elderly Demented PatientDocument9 pagesJournal Reading Managing BPSD Treating Agitation and Aggression in The Elderly Demented PatientArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Animal Ass HazardDocument10 pagesAnimal Ass HazardstreeturbanNo ratings yet

- AnaphylacticDocument16 pagesAnaphylacticArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- DIALISIS BacaDocument4 pagesDIALISIS BacabrokentinjaNo ratings yet

- Cognitve SequelaeDocument3 pagesCognitve SequelaeArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- MR Melena-Ulkus PepticDocument21 pagesMR Melena-Ulkus PepticArvindan Subramaniam100% (1)

- MR GoutyDocument25 pagesMR GoutyArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Ulkus PeptikumDocument17 pagesUlkus PeptikumArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- What is diabetic retinopathy and its stagesDocument6 pagesWhat is diabetic retinopathy and its stagesArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- What is diabetic retinopathy and its stagesDocument6 pagesWhat is diabetic retinopathy and its stagesArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- AnaphylacticDocument16 pagesAnaphylacticArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Areas: A Population Study Autism and Autistic-Like Conditions in Swedish Rural and UrbanDocument8 pagesAreas: A Population Study Autism and Autistic-Like Conditions in Swedish Rural and UrbanArvindan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Test Battery For Different Age GroupsDocument14 pagesDiagnostic Test Battery For Different Age GroupsDhana KrishnaNo ratings yet

- German Volume TrainingDocument15 pagesGerman Volume TrainingJean-Pierre BarnardNo ratings yet

- Star Senior Citizen Red Carpet Health Insurance Plan (10 Jan-19)Document1 pageStar Senior Citizen Red Carpet Health Insurance Plan (10 Jan-19)Harsh VardhanNo ratings yet

- Orthodontic Treatment Needs in Adolescents Aged 13-15 Years Using Orthodontic Treatment Needs IndicatorsDocument7 pagesOrthodontic Treatment Needs in Adolescents Aged 13-15 Years Using Orthodontic Treatment Needs IndicatorsTitis NlgNo ratings yet

- School District Safety Rating Complete ReportDocument41 pagesSchool District Safety Rating Complete ReportTMJ4 News100% (1)

- Penyakit Inf Saluran Pencernaan PDFDocument9 pagesPenyakit Inf Saluran Pencernaan PDFAde PermanaNo ratings yet

- RMLNLU Environmental Law Project on Waste Management Laws in IndiaDocument21 pagesRMLNLU Environmental Law Project on Waste Management Laws in IndiaTanurag GhoshNo ratings yet

- Relationship of Tooth Grinding Pattern During Sleep Bruxism and Temporomandibular Joint StatusDocument9 pagesRelationship of Tooth Grinding Pattern During Sleep Bruxism and Temporomandibular Joint StatusJonathan GIraldo MartinezNo ratings yet

- People Are Having More and More SugarDocument2 pagesPeople Are Having More and More SugarLâmNo ratings yet

- Wa0008Document31 pagesWa0008Ketul ShahNo ratings yet

- Powerpoint Presentation PathoDocument6 pagesPowerpoint Presentation Pathoapi-719781614No ratings yet

- Relationship of Lifestyle, Exercise, and Nutrition With GlaucomaDocument7 pagesRelationship of Lifestyle, Exercise, and Nutrition With GlaucomaValentina Gracia ReyNo ratings yet

- Puerto Rico Building Codes GuideDocument3 pagesPuerto Rico Building Codes GuideTommyCasillas-GerenaNo ratings yet

- Ananthapuramu Ap Gov inDocument9 pagesAnanthapuramu Ap Gov inEsther RaniNo ratings yet

- Funda Rle Retdem ProceduresDocument9 pagesFunda Rle Retdem Proceduresaceh lorttNo ratings yet

- Post Operative Care (P.o.c) : It Is The Care The Patient Is Received After The SurgeryDocument8 pagesPost Operative Care (P.o.c) : It Is The Care The Patient Is Received After The SurgeryJana AliNo ratings yet

- Maravilla, Dessa Fe N. BSN 3Y1-2S: Health Problem Health-RelatedDocument4 pagesMaravilla, Dessa Fe N. BSN 3Y1-2S: Health Problem Health-RelatedALIANA KIMBERLY MALQUESTONo ratings yet

- Applying 5S ProceduresDocument70 pagesApplying 5S ProceduresSanta Best100% (3)

- Filipino Teacher: G. Enrile Contact# 09661888404: Modyul 3 F10PN-Ic-d-64Document7 pagesFilipino Teacher: G. Enrile Contact# 09661888404: Modyul 3 F10PN-Ic-d-64Johnry Guzon ColmenaresNo ratings yet

- Guronasyon Foundation Inc. National High School: I. Project Title Wushu Club II. ProponentDocument2 pagesGuronasyon Foundation Inc. National High School: I. Project Title Wushu Club II. ProponentJeff Nieva CardelNo ratings yet

- Cover Letter For EportfolioDocument1 pageCover Letter For Eportfolioapi-302255572No ratings yet

- The Perception of Community Towards The ImplementedDocument7 pagesThe Perception of Community Towards The ImplementedRia-Nette CayumoNo ratings yet

- Management & Marketing: Post-COVID-19 Management Guidelines For Orthodontic PracticesDocument5 pagesManagement & Marketing: Post-COVID-19 Management Guidelines For Orthodontic Practicesdruzair007No ratings yet

- Annual Medical Examination Masterlist 2022 1Document6 pagesAnnual Medical Examination Masterlist 2022 1Alfie BurbosNo ratings yet

- Vision Research: Stephanie K. Lynch, Michael D. AbràmoffDocument7 pagesVision Research: Stephanie K. Lynch, Michael D. Abràmoffanka_mihaelaNo ratings yet

- A.bsfhsjsjsjgsg-WPS OfficeDocument3 pagesA.bsfhsjsjsjgsg-WPS OfficeGJ MagbanuaNo ratings yet