Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Politics of Everyday Life in Twenty-First Century Myanmar

Uploaded by

Hpone Myint ThuOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Politics of Everyday Life in Twenty-First Century Myanmar

Uploaded by

Hpone Myint ThuCopyright:

Available Formats

The Journal of Asian Studies Vol. 70, No. 3 (August) 2011: 641656.

The Association for Asian Studies, Inc., 2011 doi:10.1017/S0021911811000842

The Politics of Everyday Life in Twenty-First Century Myanmar1

ARDETH MAUNG THAWNGHMUNG

Myanmar has been conventionally regarded as one of the most repressive countries in the world. As a result, many scholars, journalists, and human rights organizations understandably focus their attention on the draconian policies of the Myanmarese military regime. When the country makes headlines, the story of events taking place is typically framed in terms of state oppression and direct popular opposition. This leads to a restrictive view of the political dimensions of life in Myanmar, an approach to the topic that deals with only a small number of admittedly important subjects: authoritarian governance, organized efforts to bring about systemic change, and the fate of Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel Peace Prize Laureate whose latest release from house arrest put Myanmarese politics back in the headlines in November 2010. What is left out of the pictureor given only glancing attentionare a host of social, economic, and cultural issues that also have political dimensions and implications, namely the efforts by Myanmarese citizens to carve out space for independent, meaningful action on a personal level. These actions, which have political aspects but stop short of being outright forms of dissent, will be my focus in this essay.

I present as feature of the politics of everyday life, are important because although the military regime is undoubtedly unpopular, much of the time most ordinary citizens are concerned less with bringing about a change in who governs the country, and more with addressing immediate problems. For them, politics often comes down to finding strategies to manage such quotidian matters as gaining access to food, clean water, electricity, transportation, and healthcare; figuring out how to obtain citizen IDs; and finding the most effective methods for dealing with the omnipresent local authorities. Without denying the importance of other kinds of political stories, such as accounts of the hollowness of controlled elections (such as those that took

UCH EFFORTS, WHICH

Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung (Ardeth_Thawnghmung@uml.edu) is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts Lowell

1 In 1989, the Myanmarese military junta replaced the existing English names for the country and its divisions, townships, cities, streets, citizens and ethnic groups with what it considered to be more authentic Myanmarese names. Thus Burma became Myanmar and its citizens Myanmars; Rangoon became Yangon; and ethnic groups such as the Karen were renamed Kayin. I use Myanmar throughout this piece for the sake of consistency.

642

Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung

place just before Suu Kyis release) and the continued harassment and detention of opposition figures, this essay will argue for the value of bringing into the picture the ways that local residents cope with their particular circumstances. My goal is neither to overstate the importance of these actions nor to downplay the oppressive nature of the current system, but rather to suggest, via short snapshots of particular issues and vignettes drawn from fieldwork in a country whose current situation gets little ethnographic attention, that what scholars working on varied authoritarian settings have dubbed informal adaptive strategies and everyday politics can tell us important things about contemporary Myanmar.2 My focus, like that of previous analysts of these topics, is on activities that are neither officially sanctioned nor regarded by the government as illegal; hence they fall into a gray zone. These activities emerge as a result of individual and collective efforts to work around official legal barriers through innovative arrangements and citizens attempts to reconstruct the world around them to the best of their ability to suit their needs.3 Scholars such as China specialist Kellee Tsai and Vietnam specialist Ben Kerkvliet have highlighted the significance and widespread nature of these kinds of informal adaptive strategies. I will draw here particularly heavily on the work of Kerkvliet, who defines everyday politics as actions that focus not on elections or direct dissent but on the distribution of key resources.4 He argues that a view of politics that is limited to activities initiated by national governments and to concerted efforts to influence formal authorities misses a great deal of what is politically significant, and broadens the definition of politics to include activities undertaken by corporations, industry, universities, religious groups, and families sites where the distribution of key resources also takes place. According to Kerkvliet, many of these activities reveal no political message, involve little or no organization, and usually occur by means of low-key, mundane, and subtle expressions and actions that, indirectly and privately, endorse, modify or resist prevailing procedures, rules, regulations, or the established order. Thus the activities that characterize everyday politics can range from support for, and compliance with, official rules and authorities to the modification and evasion of them, and resistance against them. What

Some of the most influential works in the vein that interests me here have been done by James C. Scott; see, for example, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987). Other important studies include Kellee Tsai, Capitalism Without Democracy: The Private Sector in Contemporary China (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007), see esp. p. 12); and Aili Mari Tripp, Changing the Rules: The Politics of Liberalization and the Urban Informal Economy in Tanzania (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), see esp. p. xv; and Ben Kerkvliet, The Power of Everyday Politics: How Vietnamese Peasants Transformed National Policy (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005). 3 Tsai (2007), p. 12; Tripp (1997), p. xv. 4 Kerkvliet (2005); his comments echo a classic definition of politics as a matter of who gets what resources, in what proportion, when, how the distribution is done, and with what justifications; see also Adrian Leftwich, ed., What Is politics? An Activity and its Study (Polity Press, 2004).

2

The Politics of Everyday Life in Twenty-First Century Myanmar

643

follows, to provide an introduction to everyday politics in contemporary Myanmar, is an extended story about a struggle relating to work and transportation followed by several short sections that zero in on specific forms of negotiations and contestation over quotidian issues.

THE TALE

OF THE

TAXI METER

In the late 1960s there were two kinds of taxis: those that used meters to calculate fares, and those where the driver and passenger negotiated a price for a given ride. Meters fell into disuse by the mid 1970s. Then, in early 2008, the Myanmar government announced that all taxis in Yangon must install a digital fare meter in order to create fair, reasonable, and affordable fees for the passengers, eliminating the negotiated fare system.5 The Weekly Eleven, a widely read local journal, estimated that by July 2008 10,000 taxis had already installed meters, leaving only a few vehicles to complete the process.6 Theoretically, passengers would welcome the meters as a way to save money, and drivers would see them as a means to ensure predictable income. In reality, two years later it had become clear that neither the taxi drivers nor local residents preferred to use meters to settle fares; instead, they continued to bargain to reach mutually agreed-upon prices. Why did this plan to install taximeters fail? This failure represents the broader challenges faced by twenty-first century Myanmar. These challenges stem not just from a lack of political freedom, but also from physical and infrastructural limitations, unsound economic policies that favor a small group of people, and a lack of public confidence in the governments ability and willingness to implement policies that would promote collective interests. Under the new scheme, for instance, passengers were automatically charged 500 kyats (approximately USD 50 cents in 2009) as soon as they boarded the taxi, and a further 150 kyats (0.15 USD) for every additional kilometer.7 Thus the fare was set too high for customers wanting to travel only short distances. In addition, factors like poor road conditions and traffic congestion that might increase fares, encouraged many customers to bargain for a set fee before they began their journey, even though the fare set by the meter might have been cheaper in the end. The taxi drivers themselves faced the opposite challenge: although they could expect a reasonable return from short journeys, the standard rate was set too low for longer distances. Some drivers complained that the rate was set too low given the high cost of repairs and spare parts.8 Other running

5 6

Kyemon, July 4, 2008, 4. In Myanmar language. Weekly Eleven, July 8, 2008, 12. 7 Myanmar Times, January 2531, 2008, 9. In Myanmar language. As of 2009 there were approximately 1,150 kyats per dollar at the market exchange rate. 8 Myanmar Times, January 2531, 2008, 9. In Myanmar language.

644

Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung

costs included increased expenses and hours wasted in long queues at gasoline stations as a result of power blackouts, and high prices for natural gas and petroleum, expenses that were inevitably passed on to customers. The kinds of challenges faced by Yangons taxi drivers are mainly infrastructural problems; one can improve conditions in the country by repairing roads and bridges, building more natural-gas filling stations, and providing adequate electricity to cut down on unnecessary waste and costs and create a more predictable physical environment. Other solutions would be to impose standard rates that reflect real market conditions (such as those that take into consideration factors such as high inflation and exorbitant repair costs for taxi drivers) and to set separate rates for short and long distances. In addition, one can boost the economy to increase the numbers of middle-class citizens who can afford to use taxis. Until the end of 2009, the number of taxis on the street exceeded the number of people who can afford to use them. The popular journal Myanmar Times, pointed out that poor economic conditions and the large number of express buses which charge cheaper fares have further reduced the numbers of potential taxi passengers, leading one author to quip: Dont even stretch out your arms when you are out strolling; chances are that a taxi will approach you assuming that you were trying to hail it.9 Another lesson to be drawn from the failed experiment with electronic taximeters is the widespread lack of trust in the governments intentions to formulate policies in the public interest. Many taxi owners and drivers have not only found it extremely expensive to install the meters, which cost 2 lakhs (equal to 200,000 kyats, or 200 USD in 2009), about three weeks income for a taxi driver),10 but also question the intentions of the government, which granted a monopoly to a few individuals to import the devices. The widespread practice of awarding import/export licenses and monopolies to trade in specific products to favored individuals has shielded them from open competition and allowed these privileged few to increase the prices of products and the cost of doing business in Myanmar. This is one of the main reasons why the cost of imported goods is extremely expensive by international standards. For instance, it cost about 1,500 USD in 2009 to install a telephone at a residential address. The market value of a second-hand 1990 Super Salon Nissan Sunny was a staggering 28,000 USD in 2008. One of Myanmars primary challenges is the government policy that favors a small segment of the community and a resultant lack of public confidence in the governments ability to implement sound economic policies for the good of the majority. Trust is also lacking among individuals. Taxi customers are generally afraid that their driver may try to rip them off by taking a longer route to increase

Myanmar Times, May 814, 2009, 7. Weekly Eleven, July 8, 2008. One driver told the Myanmar Times that he usually bring home about 5,000 kyats per day (5 USD); but there are also days when he has to pay for his taxi rental out of his own pocket.

10 9

The Politics of Everyday Life in Twenty-First Century Myanmar

645

the fare on the meter.11 Thus many customers attempt to strike a favorable deal before boarding a taxi in order to reduce the element of uncertainty. (It should, however, be noted that this situation is not unique to Myanmar). Equally important to the problem were the authoritarian practices of the military regime that, until recently, ran Myanmar. That regime had a record of implementing social and economic policies (by force if necessary) without any input from the community, and did not hesitate to take harsh measures against any hint of opposition. Thus going onto the street to protest against a policy that undermines the abilities of taxi drivers to pursue their livelihoods was not a safe option. Instead, the response from many taxi drivers to adverse circumstances has been to devise adaptive strategies or to resort to methods proven to have worked relatively well in the past, customs with which people were already comfortable. While appearing domineering and pervasive, the Myanmarese government is a classic weak state, which has limited capacities to enforce many of its policies. Several factors encourage a meter-free system. When attempting to strike a deal with a taxi driver, for instance, savvy Yangon citizens utilize local knowledge to gain a favorable outcome for themselves, just as drivers use that knowledge to increase their profits. For example, operational costs are generally lower for taxis that consume natural gas than for those that use diesel or petroleum, and a taxi that is run and operated by its owner can generally afford to accept lower fares than vehicles that are rented.12 Passengers use this knowledge to negotiate lower fares; drivers can manage knowledge of that information either to keep fares higher for those not in the know, or attempt to attract more business by lowering fares. Sometimes, customers and drivers will come up with creative and mutually beneficial arrangements to add in more customers along a route to share rides, thereby reducing individual costs, but bringing extra revenue to the driver. Passengers who travel the same route at the same time each day will often strike a mutually agreed-upon fixed schedule and rate with a particular taxi driver. Passengers may also get lucky and manage getting a good fare because the driver is desperate to take his first customer of the day, or because the driver is feeling generous and has already brought in enough fares to make a sufficient profit. For instance, a cousin of mine who shops regularly at the Ocean supermarket in Yangon made a deal with a particular taxi driver to take her home at a set price. The driver, who regularly waited for customers at a stall in front of the supermarket, would always follow her when he saw her leave the shopping center. My cousin would walk to the taxi (she knows the license plate), let the driver open the door for her, and drive her home. Once home, she paid the agreed-upon fare and alighted. All this took place without a word being said. Relating this

11 12

Myanmar Times, January 2531, 2008. Myanmar Times, May 814, May 2009.

646

Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung

story to me, she remarked with obvious enjoyment: I hate wasting time bargaining for a fare with all these taxi drivers. This method saves time and energy! Fundamental to all these informal practices is the cultivation of nar lai mu an informal and tacit agreement struck with authorities, service providers and business partners to overcome constraints, whether natural or institutional, in order to utilize the opportunity to fulfill individual and collective needs. These personalized dealings are usually hidden from public view, and their usefulness and effectiveness very much depend on ones knowledge of local circumstances and politics. Foreigners and visitors to Myanmar may prefer to rely on the taximeter, since they are unaware of the informal, local rates for various destinations. In the same way, for a variety of business dealings (as will be seen below), only local residents know whom to approach and the minimum they need to offer in order to receive services that are ostensibly free or to avoid regulations that constrain their activities, or to get a favorable deal. Thus the imposition of new rules and regulations applied to taxis are highly likely to fail in Myanmar if they do not take generalized local practices into account. In sum, it is difficult to understand the failed experimentation of the taximeter and other government projects and policies without understanding the multiple challenges faced by Myanmar and the strategies adopted by Myanmarese citizens to respond to these deficits. Many of these informal adaptive mechanisms have nonetheless succeeded in producing goods and services; conserved energy, resources and expenses; and have helped promote community support and create self-governing spaces for communities. Other reactive strategies, however, are based on non-productive, rent-seeking activities, and are having adverse consequences on collective welfare and long-term economic and political development. To expand our vision of everyday politics, I will turn now from the specific case of the taximeter to a more general subject: the way that some ordinary Myanmarese citizens deal with the challenges of living in a setting where scarcity is a fact of life.

THE POLITICS

OF

LIVING FRUGALLY

After moving from a delta village to a suburb of Yangon, Ma War rented the open space underneath the wooden-walled, tin-roofed stilt house of an old acquaintance for 10,000 kyats (12 USD in 2011) per month. She, her husband, and their two daughters enclosed the earthen-floored area with bamboo walls and tarpaulin. They pay their rent with a combined income garnered from selling fish in the bazaar and the daily wages the husband earns as a mason. A well-off neighbor has helped pay for the daughters school fees, and she, in return, goes occasionally to her patrons house to help with household chores. Ma Wars landlord, an alcoholic retired civil servant, has never married and now lives in the upper story of the house along with two nephews and his sister and uncle, both of whom are blind and ill. One of his nephews is single and is attending

The Politics of Everyday Life in Twenty-First Century Myanmar

647

high school; he helps take care of his two disabled elderly relatives in the home. The other nephew is married and has a four year-old daughter, cared for by his own parents in a village in the delta. He does odd jobs in the neighborhood, while his wife is employed as a live-in nanny for a wealthy family in Yangon city. He rarely sees his wife and daughter, but when they do make their monthly visit, the number of people living in the ten square foot house swells to eleven. Many deprived communities, in which obtaining basic services is difficult due to a mixture of governmental neglect and official corruption, have devised creative approaches to daily survival, as illustrated in the story above. These strategies often involve engaging in income-generating activities while at the same time attempting to conserve resources, capital, and energy through frugal living and recycling. Regardless of whether one or both heads of a household have employment, the most common method for ordinary families to supplement their income is to set up a home-based food stall or small grocery business. Home-based shops, which sometimes fall outside government regulation, tax, and supervision, have many advantages. They allow individuals flexibility, as owners can open the shop at their own convenience and can engage in multi-tasking by taking care of children and doing household chores. For instance, one woman whose husband was employed as a night guard at a construction site temporarily camped out at the site where she sold snacks and betel nuts to the construction workers while breastfeeding her infant and taking care of her other children. Her adult son was also employed as a construction worker. I also interviewed a mokehinka (a popular Myanmarese dish of rice noodles and fish sauce soup) seller who opens her shop from 6 am to 10 am, after which she returns home to prepare her children for school. In addition to allowing individuals to keep flexible hours, the costs of a homeoperated food stall are low, and leftover food provides a source of nourishment for the family. As one mokehinka seller on a street corner in Insein remarked: Sometimes the ability to feed our children leftover food from the shop can be considered profit even when we could not recover our investment for that particular day. Some homeless families, in fact, have taken advantage of the local municipal rules that prohibit the building of squatter homes but allow people to live in their shops, to find both living quarters and a means of making money. Another common approach used by individual families to address economic hardship is to grow seasonal vegetables and engage in small-scale animal husbandry, activities which are likewise outside government control and supervision. Naturally, this option is available only in villages and in suburbs where some open space is available. Raising pigs to sell for meat is considered an efficient way of earning a bit of income, and families lacking the initial capital often make arrangements with a patron who funds the purchase of the piglets, which are fed on food scraps collected in the neighborhood. When fully-grown, the pigs are sold for their meat and the profits are split between the patron and the family who raised them.

648

Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung

While some produce food products, others wash, recycle, and reuse materials such as plastic cups, bottles and paper. When I was growing up in Myanmar, my siblings made bags out of used paper and sold them to grocery shops for wrapping goods. Some earn a modest living by scouring their neighborhoods for second-hand materials for resale. One such trader I met in a suburban neighborhood of Yangon traveled around the area with his handcart buying up used goods from local homeowners. Sometimes, householders would grant him access to their backyard garbage pile, where he would carefully select any reusable items and pay the owners a negotiated price. He would seek to establish a rapport with his customers by offering to clean up their house or compound for free. He would then collect any used plastic, bottles, papers, and broken shoes and take them to the wholesalers, who would then sort them and send them on for recycling and repackaging. Once, he spotted a ragged doll sticking out of a dump, which he pulled out to give to his daughter. In addition, people live frugally in order to make efficient use of their space and labor. It is not uncommon for three generations of one family to be living under the same roof, where they share the chores, responsibilities, and income. Grandparents usually take care of the grandchildren while the parents go off to work. A mokehinka seller told me that she sets aside half the fish she buys from the market as ingredients for rice noodle soup, which she sells to customers, and uses the remainder for her family. She remarked: At least my family members are able to have fish every day. She also bought fish bones from the market daily to make ngapi (a salty fish paste usually eaten with rice). She continued wryly, We just have to think about ways of getting through each day. Other people attempt to find additional income by providing services of various kinds that operate in a gray zone economically. Such services are aimed at local residents and are usually offered at affordable prices. Many stay-at-home moms set up home-based seamstress or hair salon operations. At one home salon in Insein I visited, a living room was used as a waiting area for customers during the day and was transformed into a sleeping space for the family at night. A table used for displaying hair-care products during the day became a study desk for the children every evening. Some women carry jewelry samples in their bags to sell on consignment while on visits to friends. At any busy intersection in Yangon city, one can find artisans of all kinds, each specializing in repairing such items as umbrellas and shoes, or binding books. Cheap mobile mechanics can be found in many sections of the city, but most visitors would not recognize them as they appear to be merely idle residents lounging in chairs next to a pile of tools on the streetan expedient adopted to avoid arrest by the police or municipal authorities because they do not have business licenses to operate and because it is illegal to earn money on the street without one. When tipped off by friendly officials that an inspection is imminent, they quickly disappear from their usual spots.

The Politics of Everyday Life in Twenty-First Century Myanmar

649

Some services are created in response to local needs and conditions. When I visited Yangon in the summer of 2009, I learned that women had been employed by pickup truck owners to chaperone children as they commute to school. Their job was to make sure that the children get on and off the pickup truck and cross the streets safely. Parents apparently believed that their motherly instincts would make these women superior caregivers, and they were happy to supplement the womens modest wages with gifts. The parents of a schoolboy who was hit by a car while crossing the street believed that his chaperone failed to take good care of their child because they had given her insufficient remuneration. Some parents told me that these caretakers sometimes requested particular foodstuffs in return for providing better care for their children. In another example of workers adapting to local needs and maximizing their remuneration for their efforts, I interviewed a man of Indian descent who makes his living by sharpening knives and tools such as lawn mower blades, touting his services from street to street. Since most clients required his services on an occasional basis only, he took care to time his visits, coming to each location only once per year, maximizing his work time in any given location. Poorly paid civil servants and government employees also provide all kinds of informal services to supplement their incomes. According to my calculations, in 2009 a low-income family of four had average monthly expenses (for food and other basic necessities) of between 50,000 and 60,000 kyats (approximately 5060 USD at the time). A primary school teacher on a monthly salary of 30,000 kyats (about 30 USD) would often tutor students after hours to earn some additional income. Taking advantage of the university regulation that prohibits visitors from wearing Western clothing from entering the campus, security guards rented out traditional attireconsisting of Myanmarese skirts for both men and womenfor a small fee. Until June 2009, doctors graduating from Myanmarese medical schools were required to work for the government at a reduced monthly salary of 80,000 to 100,000 kyats (80100 USD) for three years in order to obtain a license to practice. Many doctors supplemented their incomes by working at private clinics, some seeing as many as 100 patients per day. It is common for local officials to request tea money in return for efficient service when processing national identity and passport applications, issuing building permits, granting vehicle licenses and inspection certificates, and so on. And it is not uncommon for government officials to request payment from individuals to smooth the way for services they request, thus condoning their clients attempts to avoid cumbersome government regulations.

THE BLACK MARKET

Rent-seeking activities are those that do not directly produce new goods or services; they are practiced by private individuals as well as by civil servants

650

Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung

and government officials. Some rent-seeking activities have arisen to circumvent official policies that have resulted in the creation of artificial prices and markets for a variety of goods and services. For example, the Burma Socialist Program Party (19741988) set extremely low prices for basic consumer goods and foreign currency transactions. Some civil servants took advantage of the gap between the official and market prices for scarce goods by abusing their privileged access to these hard-to-find products and selling them on the black market at inflated prices to those who lacked the connections needed to obtain them. Until 2007, the government rationed petroleum to car owners at around two gallons per day at a low fixed price. As a result, a black market for petroleum sprang up on almost every corner of every main street in Myanmars major cities. Many of the resellers bought diesel and petroleum from individuals (some car owners made a living simply by selling their quotas onto the black market), government employees working in the gas retail sector, and civil servants (who received a special quota).13 Later, in 2010, gas stations were privatized. Prices remained fixed, though they increased to the point that they were closer to market prices. Furthermore, automobile drivers were allowed to purchase as much fuel as they wanted. The black market remained, however, as unemployed car owners spent their time obtaining as much gasoline as they could manage and selling it in areas outside of Yangon where stations were scarce. Even after the government tried to limit the practice by implementing ration books, again limiting the amount of fuel an individual could purchase, marketers worked around the system by arranging with favored station owners to get extra shares of gasoline. For example, in November 2010, a friend of mine who was in between jobs found himself a reasonable cash flow when the black-market price for petroleum gradually went up while the government continued to impose limits on the price private gasoline stations could charge customers. Many car owners, including my friend, along with retirees and jobless citizens, began lining up at gas stations to buy the cheaper petroleum in order to sell it back to the black market at a higher price. Car owners had to wait an average of 23 hours to buy the petroleum at these private stations. Some would make small side payments to the employees of the gas stations to be allowed to queue several times at the same location, while others would go to multiple stations in the Yangon area, depending on the distance, the amount of gas each station was willing to sell at every transaction, and the duration of the wait at each station. A few car owners replaced their old 15-gallon gas tanks with 50-gallon tanks so as to buy more gas at every transaction. They would spend their entire day, from 5 oclock in the morning until 8 pm when the stations closed, making an average of 10,000 to 20,000 kyats daily (1225 USD dollars in January 2011, the time of this research). Some car owners camp out at

For instance, high-ranking government officials or university department heads received about 60 gallons petroleum and additional amounts of natural gas per month free of charge to operate government-owned cars for official purposes.

13

The Politics of Everyday Life in Twenty-First Century Myanmar

651

night to be at the front of the queue to buy gas the next morning. My friend befriended other like-minded professionals and as the day progressed would idly engage in conversation to kill time and to divert his attention from the heat of the sun blazing through the window of his beat-up pickup. Along with idle talk, those in the queue usually exchanged information (or warned each other) about gas stations that would sell their product short, and would relay the amount of gas each of these stations sell at each transaction. He remarked we dont know how long this situation will last, but as the Myanmarese saying goes, we collect water while it is raining and we will weave fabric while there is moonlightin other words, adapt to circumstances, taking advantage where possible. Some officials have used their privileged access to local money markets, where official exchange rates are overvalued, to import foreign goods (e.g., paying the government rate of around 6.5 kyats per dollar rather than the market rate of 1,150 kyats per dollar in 2009). These various activities do not create new products or services. Although they have enabled some ordinary Myanmarese to profit by participating as middlemen or selling supernumerary quotas on the informal market, ultimately the regimes policies benefit only a small group of government officials and their business partners who have ready access to these scarce goods. Rent-seeking behavior also occurs when government places restrictions on imports and exports, allowing only a few privileged individuals to engage in this highly lucrative trade. For example, when the government restricted access to imported automobiles the cost of cars increased, generating a market for illegal imports. Until 1994, private citizens (especially seafarers, overseas workers, and government-sponsored academics studying abroad) could import cars. However, after 1994 the government placed restrictions on car imports and issued import licenses to only a few individuals, pushing up prices on all vehicles available. Thus the 1986 Nissan Sunny Super salon that my husband and I bought for my parents for 5000 USD in 1995 had a market value of about 20,000 USD in Myanmar in 2008. Until 2004, many cars were smuggled in from neighboring countries. While these so-called without (i.e., without license) cars were very cheap, the government confiscated many of these illegal vehicles, leaving only a few of them, all to be found in the hands of government officials and their cronies. In Taungyi Township, hundreds of impounded cars were piled up in front of the main government building.14 Some business entrepreneurs have conspired with government officials by deliberately damaging without cars as proof that they were manufactured by the domestic automobile

14

In 2010, the government tried to sell these impounded cars to the public through auction, thereby driving down the prices of automobiles in Myanmar. Furthermore, more domestically produced cars are available, and Chinese imports have increased and are permissible, reducing the profits for black market operations.

652

Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung

industry, thereby entering the world of elite owners of foreign cars. While some ordinary Myanmarese middlemen benefited from these activities, the primary beneficiaries were the few individuals who have access to car import licenses and the government officials who confiscated illegal vehicles. The created inefficiencies (e.g., rendering so many confiscated cars useless, and large-scale sabotaging of car parts) generated considerable waste. Speculative activities constitute a further informal adaptive mechanism that, like rent seeking, do not contribute goods or services to the community. Myanmar citizens hoard rice, mung beans, or garlic, hoping to reap huge profits when prices rise. In 2008, many middlemen who had hoarded garlic lost their investment when prices dropped due to reduced demand for Myanmarese garlic in neighboring countries. When I visited the Southern Shan state in 2008, I saw piles of garlic, discarded and rotting, in private storerooms. In the same year, mung bean merchants lost billions of kyats from exporters who never paid them.15 When bean prices did not go up as much as anticipated, the exporters lost everything and could not repay the debts they owed to the mung bean merchants. This particular chain of speculation turned out to be a house of cards. Gambling the running of illegal lotteries are another form of non-productive informal practice that is widespread in Myanmar.16 Myanmarese have long been followers of soccer and some individuals, regardless of socioeconomic status, bet considerable sums on national and international tournaments. Many poor residents buy illegal lottery tickets in the hope of making a little extra income on the side, since ticket prices are cheaper and the chances of winning are higher than for the official lottery. Like other non-productive activities, the lottery creates employment for many ordinary people as ticket sellers and serves as an outlet to relieve the frustrations of the poor. However, addiction to the illegal lottery has become a widespread social problem in the country. People become mired in debt and frequently pawn and sell their possessions because of it. Couples get divorced and family relations suffer. Even fish sellers in the bazaar will ignore questions by customers while they anxiously await the release of the lucky numbers. In addition to the poverty it brings in its wake, the illegal lottery is not underwritten by any institutional or state authority, so failure to pay is always a real possibility. Thus, people who are overjoyed to win a little money run the risk of discovering that those selling the tickets could or would not pay out nor could their bosses, or even their bosses bosses. Imprisonment can result from such cases, or the illegal seizure of the

Weekly Eleven, August 5, 2009, 7. Amidst poverty illegal lottery flourishes in Myanmar, One World South Asia, 21 July 2009, accessed August 3, 2009, http://southasia.oneworld.net/todaysheadlines/amidst-poverty-illegallottery-flourishes-in-myanmar.

16

15

The Politics of Everyday Life in Twenty-First Century Myanmar

653

ticket-sellers goods by aggrieved players, but often nothing was done until recently to redress the problem.

THE WORLD

OF THE

SPIRITS

IN

EVERYDAY LIFE

Some activities that provide emotional and spiritual support that are impossible to measure in monetary terms can also be characterized as informal adaptive mechanisms because they help sustain individuals through difficult situations. The Myanmarese interest in various forms of superstition, very broadly defined, illustrates this. A broad spectrum of Myanmarese rely on supernaturalism, astrologers or advice from religious figures to help them prepare for unforeseen misfortunes or to deal with their existing difficulties. Astrologers may advise people to yadayakye (i.e., to take a specific course of action aimed at avoiding imminent misfortune). For example, Ma Chaw is an unmarried thirty-year old college graduate who has a coveted job as a TV personality for a local private station. She consults a number of astrologists two or three times a month on issues ranging from whom to choose for a spouse, her continued job prospects, to choosing names for her new-born relatives and picking appropriate dates for special events. She recalled that she was once told by a palm reader to make an offering of 23 ears of corn (she was 23 years old back then) at the pagoda in order to ward off an impending danger predicted to befall upon her. She was living in Pegu city, a two-hour bus ride from Yangon, and, because there was no corn in Pegu, had to catch transport early in the morning to search for the corn at vegetable markets in Yangon. She had to find ears of just the right sizesmall enough that they could be held in a single bunch for her offering. Because she had to visit a number of different markets in different locations, it was already getting dark by the time she arrived back to her home in Pegu with the appropriate offering, which she brought directly to the pagoda. She nonetheless went to bed happy after her long day, content in the knowledge that danger had been averted. Ma Chaw is not unique. The decisions taken by many people, from senior military officials to poor farmers, are often heavily influenced by advice offered by astrologers. Sometimes this results in not taking action: At about the same time as Ma Chaws trip, a young Myanmarese sailor in Yangon postponed his departure date for his new job assignment by one month, because his astrologist advised him to defer travel to avoid calamity. Astrologists are not the only specialists consulted for advice. People also visit Buddhist monks seeking spiritual comfort as well as advice for choosing the right lottery numbers, or consult the supernatural with the assistance of published literature. According to a survey conducted by the Yangon-based Myanmar Marketing Research and Development (MMRD) in 2008, the most popular magazine in Myanmar over the past 10 years was Nakata Yawng Kyi, which

654

Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung

deals with supernatural and spiritual issues. Nakata is categorized as gambia literature, which covers a wide range of broadly supernatural subjects including ghosts (references to which were censored by the government until seven years ago), spirits, astrology, traditional medicine, martial arts, and Buddhism.17 A story in the Myanmar Times in 2008 points out that gambia literature has become popular because it fits in with existing Myanmarese culture and social practices and provides a convenient outlet for people who have become bogged down in worldly problems.18 In an opinion survey accompanying the article, readers of gambia literature commented that the material gave them useful tips on finding peace, courage, and tranquility amid the difficulties of life, and made them appreciate the power and glory of the Buddha. Others claimed that this material taught them how to calculate the appropriate days for taking certain actions, increased their awareness of religious issues, and informed them about the uses of traditional herbal medicine as a supplement to Western medicine.19 In addition to relying on supernaturalist literature as a source of hope and inspiration, individuals look to families, clans, relatives, and their local communities as a valuable source of spiritual and emotional support based on traditional notions of mutual social obligations. One mokehinka vender, for instance, told me that a distant relative paid for her childrens tuition fees. Families who are better off provide education, shelter, and financial assistance to their economically worse-off relatives, friends, neighbors, and people for whom they are patrons. Although gift-giving to laymen is considered the least important way of earning merit in Myanmarese Buddhist religious practice, there is a strong tradition of volunteer work and private gift-giving to friends and relatives; these informal networks largely substitute for the lack of a formal organizational structure and often provide emergency assistance in a place where the states resources are lacking.20 A few examples include a rotating credit association among the fish sellers in Upper Myanmar, and my own account of a dog meat seller who was given food by his fellow vendors when his daughter was sick and could not go to work, and a collection of a handful of rice each week from each family of a church congregation to give to destitute members of the population.

Myanmar Times, January 1117, 2008, 25. The influence of Buddhist religious practices (which are mixed with local cultural practices) and supernaturalism on the lives and activities of Myanmarese is fully discussed by Manning Nash and Melford Spiro, who conducted anthropological studies in villages in Myanmar in the late 1950s and early 1960s. 19 Myanmar Times, January 1117, 2008, 25. 20 The hierarchy of meritorious acts of self-sacrifice aimed at earning kutho or merit in Myanmarese Buddhist society runs as follows: (1) building pagodas, (2) sponsoring a novice monk, (3) building a monastery and donating it to a monk, (4) donating a well or bell to a monastery, (5) feeding a group of monks, (6) feeding and giving alms to individual monks, and (7) feeding and giving hospitality to laymen. Nash, Manning The Golden Road to Modernity, (New York: Wiley,1965) see esp. p. 114).

18

17

The Politics of Everyday Life in Twenty-First Century Myanmar

655

Furthermore, many ethnic and religious organizations have been formed to address the spiritual and emotional as well as the social and humanitarian needs of their members. In addition to serving as venues for worship and cultural preservation, religious and ethnic-based organizations offer humanitarian assistance to their communities by providing education, training, health-care services, micro credit, and other support services. In a seminal survey conducted by Brian Heidel in 2006 on the growth of civil society in Myanmar, the greatest number of community-based organizations (CBOs) (236 or 52% of the total surveyed) reported working in the religious sector (on the construction of buildings for religious purposes). In addition, Myanmarese citizens may obtain support from local and international NGOs that provide services of various kinds to the poorest sections of the population.

CONCLUSION

The survey of informal adaptive strategies adopted by citizens in Myanmar provided here, via a set of fragmentary discussions of different realms of life, is by no means comprehensive. In addition to the methods introduced above, some individuals or whole families use exit strategies (that is, they leave for foreign countries in search of better employment or job opportunities, or they move to cities to search for jobs in construction, restaurants, tea shops, karaoke clubs, factories, or domestic service). Some young girls end up working as prostitutes, and others in massage parlors. Other exit strategies include alcoholism and suicide. The stories and overviews of types of activities provided above illustrate the complicated practices in the everyday lives of citizens living under a system where large political issues predominate social and political discourse. With these tales, we can better appreciate the multifaceted role of the political dimensions of life in authoritarian states. Understanding the causes and consequences of a variety of informal strategies adopted by ordinary citizens helps us re-conceptualize politics by incorporating previously marginalized viewpoints and neglected issues into broader debates about national and global politics, policy, and development. By examining everyday politics we can better address the roots of Myanmars challenges and be better attentive to the needs of the populace.

POSTSCRIPT

Beginning in early 2011, the new Myanmar government introduced a series of economic reforms aiming to address some of the deficiencies mentioned in this article. A few examples include the formulation of programs to alleviate poverty, the break up of a few import monopolies, greater lenience on the media, and a crackdown lotteries and gambling. While many of these well-

656

Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung

intentioned efforts move in the right direction, it is too early to assess the outcome and magnitude of the reforms.

Acknowledgement The author would like to thank anonymous reviewers and Mary Callahan, David Dapice, Matt Desmond, Karin Eberhardt, Merilee Grindle, Ben Kerkvliet, Ken Maclean, James Scott, Daniel Smith, Ashley South, Aili Tripp, and Lex Rieffel for their helpful comments and suggestions.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Breaking News Female PP Punished 14 Sep 09Document2 pagesBreaking News Female PP Punished 14 Sep 09Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Gara Hku Law 3Document32 pagesGara Hku Law 3HG KachinNo ratings yet

- First Regular Session of Pyithu Hluttaw Continues For Seventh DayDocument16 pagesFirst Regular Session of Pyithu Hluttaw Continues For Seventh Daymet140No ratings yet

- CIA - The World Factbook - BurmaDocument15 pagesCIA - The World Factbook - BurmawitmoneNo ratings yet

- B1a Monthly Progress ReportDocument5 pagesB1a Monthly Progress Reportchitsumyatnoe61No ratings yet

- 110 PDFDocument16 pages110 PDFZûé ZûéNo ratings yet

- Module 3Document28 pagesModule 3Daniel BrownNo ratings yet

- Colonial Rangoon Street NamesDocument4 pagesColonial Rangoon Street NamesAye Kywe50% (2)

- All Branches's AddressDocument1 pageAll Branches's AddressSai Louis PhyoNo ratings yet

- 2021 Myanmar Military CoupDocument2 pages2021 Myanmar Military CoupKYAWNo ratings yet

- Burma (Myanmar Presentation)Document26 pagesBurma (Myanmar Presentation)Sa Sai Noah100% (1)

- Opportunities of Border Trade in North East India: With Special Reference To Indo-Myanmar Border TradeDocument8 pagesOpportunities of Border Trade in North East India: With Special Reference To Indo-Myanmar Border TradeDevansh MehtaNo ratings yet

- Media Invitation PDFDocument3 pagesMedia Invitation PDFMu Eh HserNo ratings yet

- After 10 Years, Couple Say I Do': Sights Trained On Military VetoDocument68 pagesAfter 10 Years, Couple Say I Do': Sights Trained On Military VetoThe Myanmar TimesNo ratings yet

- PosterDocument15 pagesPosterHnin Yamoan KyawNo ratings yet

- List of Railway Stations in MyanmarDocument4 pagesList of Railway Stations in MyanmarMyo Thi HaNo ratings yet

- Faiceu Vol 2, No 96Document4 pagesFaiceu Vol 2, No 96nawluk3526No ratings yet

- 7 July 1962 - Dictator General Ne Win Destroyed Students Union Building in Myanmar 19Document12 pages7 July 1962 - Dictator General Ne Win Destroyed Students Union Building in Myanmar 19thakhinRITNo ratings yet

- History of Shan State - From Its Origin To 1962Document5 pagesHistory of Shan State - From Its Origin To 1962RobertNo ratings yet

- 1983 Census Book PDFDocument271 pages1983 Census Book PDFLTTuangNo ratings yet

- Situation in Wa Region - Uwsa 014 PDFDocument1 pageSituation in Wa Region - Uwsa 014 PDFmaungyukhinNo ratings yet

- Project Paramie Press ReleaseDocument2 pagesProject Paramie Press ReleaseSteve MulichNo ratings yet

- Thompson 1950, Left Wing in Southeast AsiaDocument341 pagesThompson 1950, Left Wing in Southeast AsiaschissmjNo ratings yet

- HH H KHKJFTHJNB BBBBBBGFDDocument16 pagesHH H KHKJFTHJNB BBBBBBGFDJhomar Moztera FloridoNo ratings yet

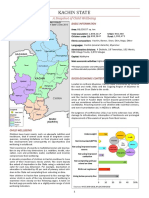

- Kachin State Profile UNICEFDocument4 pagesKachin State Profile UNICEFmarcmyomyint1663100% (1)

- Exporter Guide - Rangoon - Burma - Union of - 12-22-2017 PDFDocument26 pagesExporter Guide - Rangoon - Burma - Union of - 12-22-2017 PDFmuthiaNo ratings yet

- British BurmaDocument18 pagesBritish Burmatarek.rfh92No ratings yet

- Yangon Awards PDFDocument169 pagesYangon Awards PDFGABRIELLA SALLYNo ratings yet

- Saradaw U OttamaDocument2 pagesSaradaw U OttamaRakhine Students' Education FundNo ratings yet