Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Rise and Fall of The 9/11 Conspiracy Theory

Uploaded by

Peggy W SatterfieldOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Rise and Fall of The 9/11 Conspiracy Theory

Uploaded by

Peggy W SatterfieldCopyright:

Available Formats

Where Were You When You First Heard?

The other question I asked myself for the 10th anniversary of 9/11.

By Jeremy Stahl|Updated Tuesday, Sept. 6, 2011, at 6:59 AM ET

Soon after 9/11, conspiracy theorists began to question the origins of the tragedy I remember precisely where I was and what I was doing when I heard: I was about three weeks into my first year at Emory University in Atlanta, and I was sharing a meal with my new dormmates in the DUC dining hall. In the manner of college freshmen everywhere, we were discussing current events. It was Sept. 12, 2001, less than 28 hours after the attacks, when I heard my first 9/11 conspiracy theory. A friend was arguing that the plane that had crashed in Pennsylvania the previous day had been shot down by the U.S. military. His theory was not that the jet had been destroyed as part of some larger nefarious government plot, as some would later claim, but that it had been shot down to prevent another target from being hit. Furthermore, he argued, the Bush administration would never be able to admit this, because the public would never accept that the American government would order an American plane, over American airspace, with American passengers, to be shot from the sky. To me, the government not only would have been justified, the American people would have very easily understood that it had been justified, not to mention the fact that such a secret would be impossible to keep. We had a friendly debate for about half an hour. The next day actual details of what happened on Flight 93 began to emerge, and my friend and I didn't broach the subject again. Now that 10 years have passed, I found myself wondering: Whatever became of my friend's odd conspiracy theory? (For that matter, whatever became of him?) More generally, what has happened to the 9/11 conspiracy theory, in all its various and outrageous permutations, in the last decade? By tracing its history, and its responses to news events such as the Iraqi surge or the 2008 election or the death of Osama Bin Laden, would it be possible to show how and why conspiracy theories in generalor at least this one in particularwax and wane? Conspiracy theories thrive by appealing to existing hatred, paranoia, and uncertainty. The hatred can wither. The paranoia can crack. And the uncertainty can disappear. But the conspiracy theory lives or dies, prospers or fades, for reasons almost entirely unrelated to its actual content. Consider: Within hours of the planes hitting the towers, the conspiracy theories had already begun to swirl. Many used them to pin blame on their favorite pre-existing bogeyman. Days after 9/11, for example, a rumor spread that 4,000 Jews had been warned about the attacks and failed to show up for their jobs at the Twin Towers. As outlined in Part 1 of this series, this story was debunked immediately and never gained traction in the West. Career paranoiacs in America, meanwhile, were pointing the finger squarely at the U.S. government. People like libertarian radio host Alex Jones and alternative media reporter Michael Ruppert came from different ends of the political spectrum, but they both "knew" instantly that powers more diabolical than alQaida were behind the attacks, specifically the all-pervasive New World Order and the oilhungry, fascistic Bush administration. Soon after the attacks, Ruppert and Jones both had begun to cultivate mythologies about what really happened that day. But in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, only a tiny segment of the

American population, 8 percent according to one poll in early 2002, was inclined to believe that their government was lying to them about what happened that day. In 2003 and 2004 the Iraq war and revelations about the misleading claims that led us into it opened more minds to the possibility that the government wasn't telling the "truth"a word the conspiracists conscripted to their cause, calling themselves the "9/11 Truth Movement"behind 9/11. In the meantime, inconsistencies in the official version of events and questions about Bush's dealings with the 9/11 Commission gave full-time conspiracists plenty of ammunition with which to work. Although most Americans still believed that the Bush administration was "mostly telling the truth," by early 2004 16 percent of the population believed it was "mostly lying" about how much it knew prior to the attacksdouble the number from the same CBS poll two years prior. Mainstream Democratic politicians like Howard Dean started to tip-toe around the subject of Bush foreknowledge, while at least one member of Congress, Cynthia McKinney, embraced conspiracy theories outright. Fahrenheit 9/11, which obsessively reported Bush's connections to the Saudis and the Bin Laden family, was a smash hit, pulling in more money at the box office than any previous documentary. And in 2004, "truthers" found their intellectual apostle in an elderly professor of theology, David Ray Griffin. One year later, a film called Loose Change was released on the Internet, and by the end of 2006 it had been viewed tens of millions of times. Part 2 shows how over the course of the four years, from the start of the Iraq war to when it reached its lowest point in terms of both public support and as a military campaign, a new pool of potential adherents was created from which these conspiracists could pull their ranks. By mid-2006, one in three respondents would tell pollsters that they believed the government either orchestrated the attacks or allowed them to happen in order to go to war in the Middle East. Around this time books, conventions, and movies about the 9/11 conspiracy finally started to garner attention from more mainstream outlets. With attention came scrutiny. Yet even though most of the principal contentions behind the movement were proved to be falsemost famously, by 100-year-old engineering journal Popular Mechanicsas Part 3 illustrates, the full-time conspiracy buffs doubled down. Instead of admitting mistakes and exploring more realistic premises, the loudest conspiracists started accusing anyone who would question their findings of complicity in the cover-up. And then there was the role of anti-Bush sentiment. As Bush became a lamer and lamer duck, Bush hatred subsided, and its pool of potential adherents dwindled, the movement became prone to infighting and purges. Soon there was a circular finger-pointing squad, as detailed in Part 4. Some younger leaders, like Loose Change director Dylan Avery, were driven away by the cynicism and intense paranoia of the conspiracists around 2007, while others, like British peace activist Charlie Veitch, were accused of being government spies after renouncing their beliefs. At that point, however, the movement had already begun its decline. By 2009, with the first-ever African-American president having taken office, the number of Americans who said that Bush let 9/11 happen in order to go to war in the Middle East was at 14 percent. (Because the wording of questions about responsibility for 9/11 has changed over the years, getting a consistent measure of the public's view is difficult. But in September 2007, a Zogby poll found that 26.5

percent of Americans believed "certain elements in the US government knew the attacks were coming but consciously let them proceed for various political, military and economic motives," and 4.6 percent more said that members of the government actively aided in the attacks.) In another poll in 2010, only 12 percent of Americans said they did not believe Osama Bin Laden had carried out the 9/11 attacks. Ten years after 9/11, the 9/11 conspiracy theories are receding to where they started: on the fringe. Yet one of the primary drivers of their popularitymistrust in public institutions remains high. After a decade of war and economic catastrophe, Americans are more distrustful of their government and the media than at any time in modern history. In the final installment of this series, I ask what this rising uncertainty means for the 9/11 conspiracy theory, or for other such theories. And I check back with my old college friend. Part 1: Where did 9/11 conspiracies come from? Do you remember where you were when you heard a 9/11 conspiracy theory for the first time? Email us at slateconspiracy@gmail.com or share your story in the comments below and we'll compile the most interesting notes in an epilogue to this series.

The rise and fall of the 9/11 conspiracy theory

Where Did 9/11 Conspiracies Come From?

The fringe.

By Jeremy Stahl|Updated Tuesday, Sept. 6, 2011, at 7:00 AM ET

Alex Jones, one of the earliest and most influential 9/11 conspiracy theorists The 9/11 conspiracy theories predate 9/11. On July 25, 2001, in a two-and-a-half-hour broadcast of his Infowars TV program on a local public-access channel, Alex Jones laid out what he saw as the history of government-manufactured false-flag attacks, from the Gulf of Tonkin incident that Lyndon Johnson used to draw the United States deeper into the Vietnam War to the first attack on the World Trade Center in 1993 and the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, which Jones claimed was government-manufactured terrorism orchestrated to help Bill Clinton boost his poll numbers and suppress civil liberties. As he compared Oklahoma City to the Reichstag fire, Jones flashed the numbers for the congressional and White House switchboards onscreen. "Call the White House and tell them we know the government is planning terrorism," he said. " 'Bin Laden' "he used air quotes"is the boogeyman they need in this Orwellian phony system." Six weeks later, on the day the Twin Towers fell, Jones began his broadcast by declaring that, as he had predicted, the Bush administration had taken part in a staged terror attack. "I'll tell you the bottom line," Jones said. "98 percent chance this was a government-orchestrated controlled bombing." The controlled demolition theory remains the one great unifying dogma of 9/11 "truthers," as they call themselves. But immediately following the attacks, it was a difficult position to take. In the month after 9/11, Jones' steadfast preaching that 9/11 was an inside job cost him more than 70 of his 100-plus radio affiliates. Then again, his early stand would also lend him credibility when disenchantment from both the left and right steadily grew over the following decade. Now, Jones is back on more than 60 radio stations, with an all-time-high audience of 3 million listeners per day, and he boasts of his role in spreading the 9/11 conspiracy theory: "I am the progenitor of the entire enchilada."

But it was more than just enthusiastic "early adopters" that drove the popularity of the 9/11 conspiracy theory. Early factsseemingly inconsequential nuggets passed around the Web soon after the attacks occurredalso played a major role. By the time these facts were debunked, the theory they were adduced to support had already gained widespread acceptance. The first noticeable road sign as you enter Sebastapol, Calif., a small town two hours north of San Francisco, is for the city's fortune teller. Driving along the main drag one is similarly struck by rows of crunchy, hippie organic shops and advertisements for an interactive dinner murder mystery. It's almost clich that down a winding back road in such a place lives another founder of the 9/11 conspiracy theory, Michael Ruppert. But much about Ruppert fits the stereotype of the full-time conspiracy theorist. When I arrive at his two-acre country property, Ruppert gives me the tour of his personal garden and chicken coop, plucking an organic raspberry, a piece of lettuce, and a leaf of basil as a welcome offering. His upstairs hallway and office are adorned with photos of fellow conspiracy theorists such as Cynthia McKinney, the former Democratic member of Congress and 2008 Green Party presidential candidate. Ruppert gained a minor degree of celebrity himself two years ago after writing and starring in the critically acclaimed documentary Collapse, about his current twin obsessions of economic crisis and peak oil. He boasts that the movie made him friends with Mel Gibson and Leonardo DiCaprio, and is also a proud marijuana user. ("I used to have a column in High Times!") He is prone to bizarre rants about having predicted the current economic crisis. "I am America's Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn," he tells me in a typical non sequitur. "I'm in a gulag. Not like he was, not physically. I'm in a gulag of invisibility. The United States government and the mainstream media do not dare mention my name. I predicted all of these events, not all, but most of them, with alarming clarity." Before 9/11, Ruppert had been working on other conspiracy theoriesabout a government supercomputer program, about accusations that AIG was laundering drug money, about alleged drug-running by the CIA. He had been obsessed with the CIA and drugs ever since he says the agency tried to recruit him through his ex-fiancee, "Teddy," while he was an LAPD narcotics officer in 1976. The dramatic tale of his descent from up-and-coming cop into career paranoiac is told in Jonathan Kay's chapter on the psychology of conspiracists in his book Among the Truthers: "Within two years of meeting 'Teddy,' Ruppert checked himself into a psychiatric hospital, complaining about death threats. Soon thereafter, he left the LAPD, and began peddling different versions of his storyincluding the contention that the CIA tried to recruit him to protect its L.A.-area drug operationsto whatever credulous journalists would listen." It was Ruppert's website From the Wilderness that was one of the first to start questioning the official account of 9/11. On the morning of 9/11, Ruppert was exchanging emails with his ex-wife, who witnessed the attacks from her 35th floor Battery Park apartment. As Ruppert attempted to hold her hand virtually while she watched the North Tower burn, he watched live on TV as the second plane struck the South Tower. "As soon as the second plane hit, I knew that this was totally wrong," he told me. "I may not have reported it right away, but I was in full investigative mode from the second I saw the

second airplane hit the tower." And when the Pentagon was struck by Flight 77, it was all the confirmation Ruppert needed that the government had been complicit. Ruppert then interrupts his story to show me a closet that houses his knife collection and "personal emergency survival supplies." He pulls out a framed photo of an Air Force pilot alongside assorted combat medals and ribbons. "This is my father," he says. "He was a radar intercept officer in F-89 and F-90 interceptors stationed in Alaska waiting for the Russian bombers to come over the pole. I was raised into this culture. It's impossible under NORAD and Air Force scramble procedures for that plane to have ever hit the Pentagon. We were prepared for that from the 1950s." For Ruppert, it was inconceivable that the most expensive air defense system in the world could possibly have failed that day. Never mind that it was a system whose primary mission was to guard against Soviet encroachment for 40 years and which continued to focus exclusively on external threats in the decade following the end of the Cold War. It should have been ready, and if it wasn't, then it had to be because of internal sabotage. Lending credence to this conspiracy, the official timeline issued by military commanders in the wake of the attacks was incorrect. At first NORAD claimed that fighters were notified that Flight 77 was hijacked, and that the fighters were scrambled toward Washington in what should have been enough time to intercept the third plane before it struck the Pentagon. Eventually, using subpoena power, the 9/11 Commission was able to piece together the actual timeline of events that day, which demonstrated that contrary to previous claims, the military had not been aware of any of the hijackings before it was much too late. Though military officials were exonerated of intentionally misleading the 9/11 Commission, some staff members of the commission would later go on to describe the testimony as deliberately untrue. So the seed of one key 9/11 conspiracy theory was based on a government-propagated falsehood. The tapes of the day's events from NORAD's Northeast headquarters, eventually released to the public in 2007, would prove that there was little the fighters could have done. But by then it didn't matter. As early as November 2001, Ruppert was lecturing in front of 1,000 people at Portland State University on the "Truth and Lies of 9/11," which he recorded and soon started marketing. He went on to catalog his From the Wilderness reports into a book, Crossing the Rubicon: The Decline of the American Empire at the End of the Age of Oil, which has sold more than 100,000 copies. *** In the weeks and months after 9/11, Jones and Ruppert were already formulating a vast conspiracy theory that would take several years to reach peak popularity. There was another theory, however, that spread more widely and died more quickly, at least in the West. As such, it serves as a lesson in how and whereif not whyconspiracy theories work: by taking a small nugget of truth and constructing entire mythologies around it. It took less than 24 hours for vague theories attributing the attacks to Israel to begin to circulate. Four days after 9/11, the first piece of evidence linking Israel to the attacks was reported in

Syrian newspaper Al Thawra. The government paper stated that "4,000 Jews were absent from their work on the day of the explosions," the implication being that 4,000 Jews were forewarned about the attacks by the actual plotters, fellow Jews. The story spread through the Middle East. The original source of that precise 4,000 number was the Jerusalem Post, which reported on the day of the attacks that "[t]he Foreign Ministry in Jerusalem has so far received the names of 4,000 Israelis believed to have been in the areas of the World Trade Center and the Pentagon at the time of the attacks." Slate and popular myth-busting site Snopes.com were two of the first outlets to debunk the rumor. Yet 10 years later, morphed versions of the discredited "Jewish foreknowledge" stories are still being repeated by fringe anti-Semitic 9/11 conspiracy theorists, including Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The theory does not have much traction in America, even among 9/11 conspiracy theorists, but it has maintained consistent popularity on the Arab street, where according to the New York Times it is conventional wisdom that Jews were warned to stay home that day. A 2008 World Public Opinion poll showed that 43 percent of Egyptian respondents blamed Israel for 9/11, while 31 percent in Jordan blamed Israel, and 36 percent in Turkey pinned the attacks on the United States government. In the Palestinian territories, 27 percent thought the United States was responsible, while 19 percent said Israel had carried out the attacks. Arabic editions of the original anti-Semitic conspiracy theory, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, have been best-sellers in Syria and Lebanon, while the famous forgery was adapted for Egyptian television in a 41-part "historical drama" in 2002. In the Middle East, says Charles Hill, a 32-year veteran of the foreign service, there is a deep undercurrent of belief that just about everything that happens in the worldgood and badis due to an American-led international Jewish conspiracy. "America is kind of Jewry writ-large because 'the Jews control the media, they control committees of Congress, and they control the universities,' and such," he says. In the case of the 4,000-Jews rumor, Hill says, the very specificity of the charge lent it credibilityeven as it also allowed it to be quickly debunked. Conspiracists like a fact "that is concocted to be plausible because it is highly specific," Hill says. "And because it is highly specific, and because it has been, they claim, discovered, because it had been covered up, designed not to be known, and it was revealed by an error or by someone who stumbled across it, and therefore that proves or adds credibility to the overall charge." *** The prominence of the 4,000-Jews rumor in the Middle East to this day and its failure to catch on in the United States is illustrative of a crucial fact of the popularity of conspiracy theories: They need fertile ground in order to flourish. In the early days after 9/11 in the United States, the fields were relatively fallow. But within 18 months of 9/11, that would begin to change.

Part 2: The rise of 9/11 conspiracism.

The Rise of "Truth"

How did 9/11 conspiracism enter the mainstream?

By Jeremy Stahl|Updated Tuesday, Sept. 6, 2011, at 7:01 AM ET

George W. Bush gets word of the 9/11 attacks while reading a book to schoolchildren In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, conspiracists started to create and spread what would ultimately become the foundational mythology of the 9/11 conspiracy movement: In order to suppress civil liberties and benefit their allies in the oil and gas industry, hawkish neoconservatives in the Bush administrationalong with their partners in the CIA and FBI, of courseorchestrated a massive terror attack that killed 2,977 innocent civilians and mobilized the American populace behind otherwise unsupportable wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. There is no consistent polling about the popularity of this theory. But in the early years of the decade, at least, it was relegated to the far reaches of the American political spectrum, a place memorably described in Richard Hofstadter's Paranoid Style in American Politics. In May 2002, with Bush's approval rating still well over 70 percent, fewer than one in 10 Americans in a CBS News poll said that the Bush administration was lying about what it knew regarding possible terror attacks prior to 9/11. By April 2004, 16 percent of respondents in a CBS Newspoll said that the Bush administration was "mostly lying" about what it knew about possible terrorist attacks against the United States prior to 9/11, while 56 percent said it was telling the truth but hiding something and 24 percent said it was telling the entire truth. By the five-year anniversary of the attacks, one in three Americans would tell pollsters that it was likely that the government either had a hand in the attacks of 9/11 or allowed them to happen in order to go to war in the Middle East. What caused these ideas, by the middle of the decade, to enter the political mainstream? It's hard to say whether widespread discontent and mistrust makes people more willing to listen to ideas

they previously considered absurd. But it seems plausible. And there can be little doubt that by the middle of 2006, 9/11 conspiracy theorists had a new base to draw from. That base was general unhappiness with the war in Iraq and a small but deep strain of Bush hatred. *** The 9/11 conspiracy theories got a hearing in Europe and among liberal intellectuals like Gore Vidal before they rose in popularity in America. French author Thierry Meyssan's 9/11: The Big Lie, which postulated that the Pentagon was not struck by a jetliner but by a smaller military aircraft or a missile, was the No. 1 best-selling book in France for six weeks in the spring of 2002. By October, Vidal was seriously exploring a wide range of conspiracy theories that the Bush administration had been complicit in 9/11 for geostrategic reasons in an essay in Britain's Observer. At home, such talk remained on the fringes of political life even as the war got under way. But fueled in part by anger over the deceptions of the war, the lack of accountability or disclosure on the part of the Bush administration with respect to the 9/11 Commission, and civil liberties abuses in the aftermath of the attacks, the popularity of conspiracy theories was steadily growing in 2003 and 2004. Then, in the summer of 2004, Michael Moore's Fahrenheit 9/11 was released, earning more than $100 million to become the top-grossing documentary of all time. While Fahrenheit 9/11 does not allege any sort of Bush-led conspiracy concerning 9/11, the film does depict a government hell-bent on covering up how much it knew prior to 9/11 and using the attacks as a false pretext for a war with Iraq. In 2004, more and more Americans were willing to raise these kinds of questions. Bush derangement syndrome, as Charles Krauthammer would famously call the emerging trend of Bush hatred, had not yet reached a boiling point. But it would. Within three years of his film's release, Moore himself would start giving credence to some of the more outthere conspiracy theories.

When I asked several leading 9/11 conspiracists who or what inspired them to join, they did not nameself-proclaimed founding father Alex Jones.As popular as Jones is, and as much influence as he has had in spreading the 9/11 conspiracy theory, the 37-year-old Texan new-media provocateur is not the movement's intellectual leader. That title belongs to the grandfatherly 72year-old academic David Ray Griffin. On 9/11, Griffin was a well-respected professor of philosophy at the Claremont School of Theology in Southern California. Believing that the attacks had been prompted by overly interventionist American foreign policy, Griffin shortly thereafter began working on a book about American imperialism. He was two-thirds of the way through with the project when, in March 2003, a colleague sent him a link to Paul Thompson's terror timeline, a go-to source among 9/11 researchers of all stripes. The timeline includes more than 5,000 reports that catalog every mainstream media account that could be cited as demonstrating inconsistencies in the official story or the possibility of government foreknowledge. It describes dozens of warnings about an upcoming terror attack prior to 9/11, all reported in mainstream media, and points to allegations that members of the Pakistani-ISI had aided the 9/11 attackers, strongly implying that the CIA also knew. At the time that Griffin picked up the timeline, it also pointed to inconsistencies in NORAD's story and wondered aloud why the planes had not been intercepted. All of this was simmering in Griffin's mind in March 2003. "We realized how important 9/11 was when we saw it wasn't just attacking Afghanistan, but then using that to go into Iraq," Griffin told me. When one of his students asked him to put together a presentation about 9/11 as the pretext for the war in Iraq, Griffin obliged. Soon after he began working on a magazine article based on the presentation, which would eventually become too sprawling for a periodical. It became The New Pearl Harbor, published in 2004, the first of more than 10 books Griffin has written about 9/11. Although it relies upon factual inaccuracies, leaps of logic, and selective quotations to create a complex web of conspiracy leading to the top of the Bush administration, Griffin's work is still held up by 9/11 conspiracy theorists as a masterpiece of the genre.

*** Former University of Wisconsin lecturer Kevin Barrett, who is the leading advocate of theories that Israel's Mossad orchestrated the 9/11 attacks, is one of the conspiracists who cites Griffin as his inspiration for joining the movement. Barrett came to renown in 9/11 conspiracy circles in 2006 after being castigated on Fox News by Sean Hannity and Bill O'Reilly during a national debate about the 9/11 conspiracy theory and academic freedom on the Madison campus. Though he had his doubts about the mainstream account, Barrett had dismissed 9/11 conspiracy theories as ridiculous speculations prior to 2003. But after hearing that Griffin was "marshalling the evidence" for the case that the Word Trade Center had been brought down by a controlled demolition and the Pentagon had been attacked by a military aircraft, Barrett decided to do more research. After two weeks of reading the work of Ruppert, Meyssan, and others, he was convinced. "I kind of went from saying, 'Well, this is really interesting that somebody as sensible and careful and empirical as David Ray Griffin would give credence to these pretty bizarre speculations,' to two weeks later, 'My God, this is absolutely right.' " Over the next several months he held teach-ins on the Madison campus. But he never took his activism beyond that until just days after President Bush's re-election. It was the second battle of Fallujah, which took place during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, that caused Barrett, who had converted to Islam years before, to become a full-time activist. "The images and the stories coming out of Fallujah were so atrocious," he said. "That actually was the moment when I said, 'Well, I need to take this to the next level. What can be done to stop this growing war?' " After Fallujah, Barrett decided to start a group called the Muslim-Jewish-Christian Alliance for 9/11 Truth. After losing his teaching job, in 2007, he turned his attention to conspiracism full time, and he continues that work to this day. *** In mid-2002, an 18-year-old from upstate New York named Dylan Avery discovered Paul Thompson's timeline of terror. Like David Ray Griffin, Avery was impressed, and he soon became convinced that the government was not revealing the whole story of 9/11. Avery started working on the screenplay for a feature film about a group of three friends who discovered a government cover-up. The Bush administration's lack of complete cooperation with the 9/11 Commission, along with the powerlessness of anti-war protesters to slow the march to war in Iraq, drew him to the community of 9/11 conspiracists in 2003 and 2004. "It was just so easy to believe anything terrible about your government because you were seeing all of these terrible things," Avery told me. "They were doing all of these terrible things right in front of our faces, so why wouldn't they do terrible things behind closed doors?" After realizing that a full-budget action feature was too ambitious for an 18-year-old director, Avery decided to turn his film into a documentary. Working with his childhood friend Korey Rowe, who had just returned from a tour of duty in Iraq, Avery cut together an 82-minute documentary that compiled many of the more out-there conspiracy theories about 9/11, including the charge that the South Tower was not struck by a United Airlines commercial flight but rather a military drone.

The film, produced for $2,000, was released in April 2005. At the time, Avery was working as a waiter at Red Lobster. It didn't do spectacularly well. Avery struggled to get Alex Jones to cover it on his website, and the movie was attacked by others in the movement for its factual problems. In response to the criticism, Avery cut a new edition and released it at the end of 2005, which turned out to be "the perfect time." Discontent with the Iraq war, and the Bush administration generally, spiked in 2006 as sectarian violence tipped into civil war. A majority of Americans consistently said that the Bush administration had deliberately misled the public about whether Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, while 58 percent said the government was misleading the public about how the war was going. Bush's approval rating sunk to new lows. "The distrust built up over time," Avery said. "It led, I think, to the culmination of the movement in 2005, 2006, which is when a lot of people had these doubts that were building up over years, but didn't really have an outlet for it." In July 2006, a Scripps-Howard poll found that 36 percent of Americans said it was "somewhat likely" or "very likely" that federal officials assisted in the 9/11 attacks or took no action to stop them because they wanted the United States to go to war in the Middle East. A Zogby poll one year later found 31 percent saying that elements of the government either orchestrated the attacks or let them happen for geopolitical reasons. The re-cut version of Avery's film became the most influential piece of 9/11 conspiracy agitprop, attracting tens of millions of views or downloads on YouTube and other sites. Mainstream media outlets started hounding Avery and Rowe for interviews. In the summer of 2006, Avery says, "Vanity Fair came to our house. CNN came to our house. MSNBC. CNN. Calls would not stop." But Avery's faith in the theory, like the intensity of Bush hatred in the population generally, has faded with time. "Nobody really seems to care anymore," he says. "I don't know what it was, but I guess that climate of fear during the Bush administration, while it certainly was oppressive and made us feel like Big Brother was literally lurking around the corner, it got people off their ass. It made people active, it made people want to join the anti-war movement." Since 2006 Avery has re-cut the film twice more, removing some of the more outrageous accusations, like the claim that Flight 93 had been diverted to Cleveland Hopkins Airport rather than crashing in Pennsylvania and that calls made from the plane had been faked using "voicemorphing" technology. After interviewing some of the Pentagon witnesses in person, Avery has even backed away from the stance that it was a missile and not a plane that hit the Pentagon. "It's easy to come to conclusions when a) you don't have a lot of information at your disposal and b) you haven't had a chance to actually talk to people who were there," Avery says. *** What does Avery think of 9/11 conspiracy theories now? He thinks that while orchestrating the attacks was beyond the scope of the Bush administration, there was "considerable foreknowledge" within the government so that it should have been able to prevent them. Why it did not is his new focus. "Where I am now is, I've whittled it down to a very basic statement that I think a lot of people can agree on: There was a cover-up of some kind," Avery says. "The only

question is what they were covering up, how far [up] it goes, how deep it runs, and how many asses would be on the line if the truth actually came out." He says he still "support[s] the movement," but he also acknowledges getting "sucked in" deeper than he should have been, into a "hardcore mentality that it was almost too easy to get into back then, because the war had just started and everybody was just so pissed off." "It was easy to distrust everything," he says, "because there was nothing you could trust."

The Theory vs. the Facts

9/11 conspiracy theorists responded to refutations by alleging more cover-ups.

By Jeremy Stahl|Updated Wednesday, Sept. 7, 2011, at 7:31 AM ET

Thomas H. Kean, chairman of the 9/11 Commission It's difficult to pinpoint a precise moment when the popularity of the 9/11 conspiracy theory peaked, though it was probably sometime in 2006. In tracking its decline, however, three dates stand out: July 22, 2004, when the 9/11 Commission released its final report; Feb. 3, 2005, when Popular Mechanics published its 5,500-word article dismantling the movement's claims; and Aug. 21, 2008, when the National Institute of Standards and Technology issued the final portion of a $16 million study investigating the cause of the collapse of the Twin Towers and a third World Trade Center skyscraper that was not hit by a plane. Facts alone are insufficient to destroy a conspiracy theory, of course, and in many ways a theory's appeal has more to do with the receptiveness of its audience than the accuracy of its details. The popularity of the 9/11 conspiracy theory would continue to ebb and flow after each

of these reports. But their responses to these challenges show how followers of the 9/11 conspiracy theory changed their emphases and argumentsor, more often, did notwhen presented with new information. *** The Popular Mechanics article may never have been published were it not for a $3 million national ad campaign by an eccentric millionaire to promote a self-published book called Painful Questions. The campaign posited that the World Trade Center was brought down in a controlled demolition and that the Pentagon was never hit by a jetliner, and asked questions about whether the fires in the Twin Towers were sufficiently hot to bring about their collapse or whether the hole in the Pentagon was big enough to fit a commercial airplane. When Popular Mechanics Editor James Meigs saw the ad, he says, "I thought, well, we're Popular Mechanics and we've been reporting about what happens when planes crash, how skyscrapers are built, for 100 years. Let's actually answer the questions." So the magazine went about reporting out some of the most interesting and serious conspiracy theories, and responding to them based on interviews with more than 70 experts in aviation, engineering and the military. Its article found that all of the supposedly scientific evidence for government involvement in 9/11 was based on shoddy research and, to a large extent, manipulated and misleading argumentation. The piece remains the most widely read story the magazine has ever published, with more than 7.5 million page views. "We were the first people to actually take the conspiracy theory claims seriously and address them very directly," Meigs says. "And the reaction was so overwhelmingly hostile, and kind of scary, that it was a real education in how these groups work and think." Among the responses was a report by anti-Zionist conspiracist Christopher Bollyn, who claimed to have discovered why the 100-year-old engineering magazine would take part in a government cover-up of the crime of the century: A young researcher on the magazine's staff named Benjamin Chertoff was a cousin of then-Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff, and the magazine was seeking to whitewash the criminal conspiracy with its coverage.

Never mind that Chertoff had not been in his position when the story was being written, and Benjamin Chertoff had never met the man who he said might be a distant cousin. The mere mention of the connection was sufficient for conspiracists to dismiss the report. "That was interesting. A little bit scary I think for Ben, but also kind of comical," Meigs said. "Imagine the scenario. Let's say somebody at Slate is related to Dick Cheney and all of a sudden he said, 'Hey guys, I need everybody to work with me on this: We're going to all get together to cover up the biggest mass murder in American history. Are you with me?' " The Popular Mechanics article was turned into a book called Debunking 9/11 Myths, which came to include interviews with more than 300 sources and eyewitnesses. David Ray Griffin responded with his own book, Debunking 9/11 Debunking in 2007, in which he reiterated theories that he said had not been adequately debunked, claimed that the only successful debunking Popular Mechanics had done was of straw men, and repeated the Chertoff cover-up accusation. It's worth lingering over Griffin's response to illustrate a typical reaction among conspiracy theorists to refutation. One of the bedrocks of the conspiracy theory is that U.S. military planes should have been easily able to intercept any of the four hijacked airplanes on 9/11 to prevent the attack. The Popular Mechanics article notes that only one NORAD interception of a civilian airplane over North America had occurred in the decade before 9/11, of golfer Payne Stewart's Learjet, and that it took one hour and 19 minutes to intercept before it ultimately crashed. Based on initial reports that misread the official crash report, conspiracists had previously cited the Stewart case as evidence that it normally only took NORAD 19 minutes to intercept civilian aircraft. "That's a very debated thing," Griffin told me. "It looks like somebody has kind of changed the story there. I don't know what happened, but I've read enough about it to look like that's not true

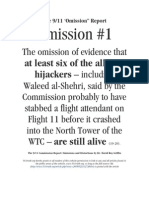

that it took that long." And what about other physical evidence that debunks the interception theory, specifically the NORAD tapes, which document the chaos and confusion of American air defenses that morning in painstaking detail? Griffin's response is that the tapes have likely been doctored using morphing technology to fake the voices of the government officials and depict phony chaos according to a government-written script. It's not surprising, he says, that after 9/11, mainstream historical accounts would be revised to fit the official narrative. "This is a self-confirming hypothesis for the people who hold it," Meigs says. "In that sense it is immune from any kind of refutation and it is very similar to, if you've ever known a really hardcore, doctrinaire Marxist or a hardcore fundamentalist creationist. They have sort of a divine answer to every argument you might make." *** Another article of faith among conspiracy theorists is that the conspiracy would not have to have been very large. In Crossing the Rubicon, Michael Ruppert writes that there didn't have to be any more than two dozen people with complete foreknowledge of the attacks to orchestrate 9/11, and that they would all be "bound to silence by Draconian secrecy oaths." But those numbers begin to balloon out of control if all of the people and institutions accused of playing a part in the cover-up are counted. They would have to have included the CIA; the Justice Department; the FAA; NORAD; American and United Airlines; FEMA; Popular Mechanics and other media outlets; state and local law enforcement agencies in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and New York; the National Institute of Standards and Technology; and, finally and perhaps most prominently, the 9/11 Commission. Of the alleged conspirators in the cover-up, few play a greater role than Philip Zelikow, the 9/11 Commission's executive director. A career academic and diplomat, he was asked to resign from his post in 2004 by representatives of 9/11 families because of an alleged conflict of interest stemming from his role on George W. Bush's transition team. Zelikow recused himself from any part of the investigation dealing with the time period that he worked with the transition team, but his presence on the commission is all the conspiracists needed to discredit the entire report. "I play a very prominent part in their demonology of the world, but the people themselves don't come across like raving lunatics," Zelikow says. "They're often people who in many respects seem quite sincere, very concerned, very patient. They just are fixated." The obsessive nature of conspiracism makes it very difficult to discuss or debate issues with some of the more hardcore believers. "They're not really able to listen to you," Zelikow says. "It's almost like you'll say something and then the tape will just replay its loop again." In 2007 a conspiracist confronted Zelikow in public with the "fact" that many of the hijackers are still alive. Zelikow responded that the 9/11 Commission had looked into the claims and found nothing to them but could not fit every single debunked conspiracy theory into the final version of the report. The questioner's reply was to repeat his accusation. I had a similar experience on the same topic when questioning Griffin, who begins his book The 9/11 Commission Report: Omissions and Distortionswith the "hijackers are still alive" theory. I sent him an email pointing out that this theory relied on discredited media reportsthe "hijackers" they had found were just

people with the same names as the hijackers. In response, he emailed me a chapter on the topic from one of his books and said he was too busy to discuss the issue further. Another common conspiracist tactic is to obsess over minor points of contention and exaggerate the importance of often easily explained inconsistencies in very hard evidence, such as phone calls victims made to family members on the ground describing the hijackings. For example, Griffin says that the phone calls, records of which were made public as part of the 9/11 Commission, were faked by "voice-morphing" technology that fooled family members on the ground. *** All the same, some conspiracy theorists have actually retreated from their more difficult-to-prove claims, such as the argument that no commercial plane hit the Pentagon. "They are focusing most of their attention on the World Trade Center stuff, where they're clinging to a few of these now pretty well-rebutted engineering hypotheses," Zelikow says. The most successful purveyor of these hypotheses is Architects and Engineers for 9/11 Truth founder Richard Gage. In March 2006 Gage heard Griffin argue on the radio that quotes from firemen provided evidence of controlled explosions in the World Trade Center. Gage was floored. "I couldn't even get back to the office, I had to pull the car over," he says. Gage tried to attend a Griffin lecture in Oakland the very next day, but the 600-person hall was full and he had to settle for listening to a live webstream. Within a couple of weeks he had created a PowerPoint presentation about this theory and started proselytizing to co-workers. Two months later he started Architects and Engineers for 9/11 Truth, and soon after that he became a full-time activist, spreading his message that the World Trade Center investigation by the National Institute of Standards and Technology was a fraud and that there needed to be an "independent" investigation. The petition he started at the time now has signatures from more than 1,500 licensed or degreed architects and engineers, and he is considered one of the movement's most persuasive leaders. Like Griffin, Gage argues that the three-year-long, $16 million NIST investigation, the work of nearly 100 NIST investigators, staff, and independent experts and consultants, was part of the criminal cover-up. "We're calling for a federal grand jury investigation of the lead investigator and his co-project leader," Gage says. "Whoever's names are on those reports need to be investigated." Dozens of peer-reviewed papers have been written that support the official hypotheses, but those are dismissed as well. Both Gage and Griffin do, however, point to the movement's own peerreviewed paper, published by former BYU professor Steven Jones and Danish scientist Niels Harrit. Because traditional controlled demolitions would have been audible throughout lower Manhattan had they actually occurred on 9/11, conspiracists have been forced to posit a very obscure scientific explanation for their central thesis: that the demolitions used an incendiary chemical called nano-thermite. Jones and Harrit argued in their paper that they found traces of a thermitic reaction in particles of dust found at the World Trade Center. Griffin and Gage hold this up as mainstream validation of the movement's work, but the peer-

review process of the paper is suspect. (The editor of the journal resigned over the paper after it was published without her approval, for example, and one of the paper's peer reviewers is a 9/11 conspiracist who has speculated that the passengers on the four flights are actually still alive and living off of Swiss bank accounts.) "Since they can't attack the science, they attack the peerreview process," Gage responds. "Let's have them attack the science." The science has been addressed by Popular Mechanics and others. At a certain point, though, debating science and theory and ideas is an exercise in futility, because the hypotheses of conspiracy theorists are not grounded in any kind of a larger understanding of the real world. "This sounds really mean," says Erik Sofge, a reporter on the original Popular Mechanics piece and an occasional contributor to Slate. "But really, it's like arguing over the marching speed of hobbits." Part 4: Paranoia and apostasy.

You're Not Paranoid if It's True

What happens when believers in 9/11 conspiracy theories change their minds.

By Jeremy Stahl|Updated Thursday, Sept. 8, 2011, at 7:14 AM ET

Nano-thermite figures heavily in some 9/11 conspiracy theories

The man who created the single most influential piece of propaganda about the 9/11 conspiracy is now ambivalent about the movement he helped make popular. "There's a certain thing called tact that you need when you're dealing with the public," says Dylan Avery, director of the film Loose Change, released in 2005 and since viewed tens of millions of times online. "And I think that is a certain approach that a lot of people lack." Avery should know. He has been accused of being a traitor, a spy, orslightly more charitablyjust plain "sloppy." According to 9/11 conspiracy proponent Michael Ruppert, the movement has been hurt by its acceptance of some of the (relatively speaking) more absurd notions that were featured prominently in the early versions of Loose Change, notions that he says were planted as disinformation by those looking to discredit conspiracists. "That's one of many reasons why I completely cut myself off from the 9/11 Truth movement in 2004," Ruppert says. "They just swallowed too many poison pills." That's the thing about conspiracy theories and the people who believe in them: One man's poison pill is another's smoking gun. For much of the decade, 9/11 conspiracy theorists were united by (and benefited from) opposition to the war and hatred of George Bush. Not even direct assaults on the facts underlying their theories had much impact. As it turns outas it usually turns out with conspiracy theoriesthe people most adept at weakening the "9/11 Truth" movement were the truthers themselves. Because conspiracy theorists can't just have disagreements. If you disagree with a conspiracy theorist, then you probably belong to the conspiracy. *** In 2008, Alex Jones' website alleged that young New York-based conspiracist Nico Haupt was actually an undercover agent. Haupt was one of the very first conspiracy theorist leaders, starting to research and organize on the morning of 9/11. He was the first to report some of the military training exercises that were going on during the attacks, which Ruppert called "the holy grail" of 9/11 research and which the movement would use to argue that the military had been sabotaged from within. But in 2005, Haupt started preaching a theory, referred to disparagingly by other conspiracists as the "no-planer" hypothesis, that the footage of jetliners hitting the WTC seen live on TV that morning was actually of holograms. Around that time, he started accusing other leaders in the movement, including Jones and David Ray Griffin, of being government plants themselves. At the end of 2006 he nearly got in a fist fight with Rolling Stone columnist Matt Taibbi, and by May 2008 he was accused of assaulting fellow conspiracists protesting at Ground Zero. He has not really been heard from since, says Ruppert, who calls him "a fringe guy who had a good heart who went crazy." Jones would disagree. He and Luke Rudkowski, a young activist who has been described as a Jones protg, took Haupt's increasingly outlandish behavior and violence as evidence that he was co-opted by the government. "This is a classic COINTELPRO operation, straight out the 1960s," Jones' website reported.

Conspiracists are not being entirely irrational when they express their fears of government infiltration. The FBI's counterintelligence operation, known as COINTELPRO, spied on and sometimes infiltrated suspected Communist groups, civil rights groups, anti-war activists, and hate groups, among others, until the program was exposed and shut down in 1971. The FBI was using some of these tactics, including surveillance of journalists, as late as 1987. COINTELPRO has become shorthand in the 9/11 conspiracy world for almost any source of information that a conspiracist disagrees with. Because there are so many disparate elements in the 9/11 conspiracy theory world, the charges will often be lodged against fellow conspiracy adherents. The key piece of evidence cited to allege that government still spies on conspiracy groups is a 30-page 2008 paper titled "Conspiracy Theories" co-written by Cass Sunstein, the current administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. In it, Sunstein says that domestic and foreign conspiracy theories pose "real risks to the government's anti-terrorist policies" and argues that the government should be "cognitively infiltrating" groups that purvey these theories. Sunstein proposes having the government send undercover operatives and paid "independent" contractors onto online message boards and websitesand into some real-life groupsin order to undermine the theories. There's no evidence that such a program is currently being undertaken by the Obama administration, but the paper set the conspiracy world aflame. "Cognitive infiltration" has become the latest buzz phrase in conspiracy circles. (Griffin devoted his last book to the topic.) In late June, one of the first alleged "cognitive infiltrators" was uncovered. *** Charlie Veitch is a 31-year-old British anarchist living in London. On 9/11, he happened to be on vacation in Thailand and remembers watching a TV in a beachside bar as the towers burned. He cut his trip short and soon took a job in the City, London's Wall Street. He did not encounter his first 9/11 conspiracy theory, he says, until 2006, when he watched Alex Jones' TerrorStorm, which describes a history of alleged false-flag terror attacks and then makes the case that 9/11 was such an event. Veitch was instantly hooked. He started to watch all of the 9/11 conspiracy videos he could find on the Internet, which turns out to be quite a few. In 2009, Veitch lost his job. By then he had started occasionally posting videos to YouTube of himself and friends heckling Scientologists or breaking out into song during the "People's Question Time" with London Mayor Boris Johnson. After losing his job, Veitch started making the guerilla videos on a full-time basis and launched an activist group called the Love Police devoted to "confronting the authority state" in the United Kingdom.

Nineteen days after starting the Love Police, Veitch caught the attention of Alex Jones with a video of himself being confronted by police officers after trying to film the U.S. Embassy in London. Jones invited Veitch onto the show to discuss what they described as the U.K. police state, and Veitch became an occasional guest. Veitch's site gained a following, which in turn allowed him to solicit enough donations to afford to pay the rent. He also started appearing occasionally on Russia Today, the Russian-sponsored propaganda TV network that traffics heavily in conspiracy theories. In June 2010, Veitch was arrested while doing his provocateur thing at the G-20 summit in Toronto, and he was arrested again the day before the royal wedding in April on suspicion of "conspiracy to cause a public nuisance." He remained a relatively minor figure in the 9/11 conspiracy world. Then he was selected as a subject in a documentary called 911 Conspiracy Road Trip, to be broadcast on the BBC this week. The documentary shows five British 9/11 conspiracy theorists as they travel to Ground Zero, the Pentagon, and Shanksville, Pa., where they meet people directly affected by the attacks. Veitch was given the chance to grill controlled-demolition experts, professors of metallurgy, some of the people who helped build the World Trade Center in the 1970s, retired CIA analysts, eyewitnesses, and aviation experts. In Pennsylvania they also spoke with Alice Hoagland, the mother of Mark Bingham, one of the passengers on Flight 93 who helped fight the hijackers. By the third day of actually speaking with people he had believed responsible for covering up mass murder, Veitch was starting to believe he was wrong about 9/11. "After meeting all of these alleged conspirators that were supposed to be in on it, I realized they were normal family men," Veitch said. "There wasn't anything conspiratorial about them." It was when he questioned a demolitions expert atop the rebuilt World Trade Center 7 that he finally changed his mind about 9/11.

"It's not so much a matter of technical evidence, it's more of a change in mindset that I've had," Veitch said. "Going from a paranoid mindset to a less paranoid mindset." *** Veitch announced his "conversion" on June 29, 2011, on his blog and YouTube channel, saying that he hadn't been wrong to believe that the government was capable of orchestrating 9/11, but he had been wrong about the facts: I think because the government has lied about the weapons of mass destruction in Iraq and hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians have been killed, we do suspect foul play when other terrible events [happen] and if governments can lie and kill half a million people, why wouldn't they lie about killing 3,000? It doesn't take an incredible leap of fantasy or faith or gullibility. We're not gullible, we're just truth seekers. And the 9/11 Truth movement is trying to find out the truth about what happened. [But you should] not hold onto religious dogma. If you're presented with new evidence, take it on, even if it contradicts what you or your group might be believing or wanting to believe. You have to give the truth the greatest respect, and I do. This relatively mild renunciation by a relatively minor advocate of 9/11 conspiracy theories was treated as major news in the conspiracy community. Veitch received threatening phone calls and emails. Donations to his site dried up. He was accused of having taken a payoff from the BBC, of having been subject to mind control by "neuro-linguistic programming experts," of being under hypnosis by British illusionist Derren Brown, and of being a Sunstein-sent cognitive infiltrator. "The best theory I heard has been that I have been deep undercover MI6 or CIA agent," Veitch said. "[They say] I was basically a one-man sleeper cell waiting to discredit the 9/11 Truth movement and destroy what they call 'the resistance' from within." Last month, Veitch's site was hacked and a message was sent to his 15,000 subscribers calling him a child abuser. "When your mom phones you saying, 'Why have you sent me something admitting to being a child molester?' it's not very good," Veitch said. "People went ape-shit over this Charlie Veitch, I couldn't believe it," says Avery, director of Loose Change. "I was like, 'Really?' I mean, I had never even heard of this guy until now." But in the 9/11 Truth movement, apostasy at any level just provides another excuse to unleash paranoia. It's this mentality that has pushed Avery away from the movement over the last four years. "Maybe he just changed his mind," Avery said, referring to the Veitch hysteria. "I mean, people change their minds." Avery has had his own issues with Jones and his audience over the years, and speculated that some of the death threats that Veitch received came from Jones' listeners. "That kind of mob mentality [is] the very thing that we were claiming to fight, the 'You're with us or with the terrorists' mentality," he said. "That's one of the reasons I had to back away from the movement in general," he said. "I was afraid I was becoming one of themsomeone who sees conspiracy around every corner."

Tomorrow: Why the 9/11 conspiracies live on.

Why Trutherism Lives On

The 9/11 conspiracy movement has faded, but the conspiracy theory will never die.

By Jeremy Stahl|Updated Friday, Sept. 9, 2011, at 7:17 AM ET

President Barack Obama announces that the U.S. has killed public enemy No. 1, Osama Bin Laden When Navy SEALs killed Osama Bin Laden in a nighttime raid on May 2, many in the media wondered whether a new conspiracy group of "deathers" would rise up to replace the recently deflated bubble of "birthers." The number of potential "deathers"those who doubt Bin Laden is deadranged between 12 percent and 15 percent, according to a pair of May polls from Fox News and Zogby. Among 9/11 conspiracy theorists, though, it is practically a given that the May raid was a hoax. Many believe that Bin Laden died long ago, probably in 2001, and that the video and audio recordings of him broadcast over the years were government-manufactured fakes. The May 2 raid "was Barack Obama saying we're getting our ass kicked in Afghanistan, the empire is collapsing, let's do a phony show to kill Osama, declare victory, and go home," said early 9/11 conspiracy theorist Michael Ruppert. Ruppert believes that Obama needed Bin Laden

killed in order to be able to justify his Afghanistan troop withdrawal plan. The new plan, according to Ruppert, is to send those troops to Iraq, "or to get them back home for civil unrest here. Which is going to happen, like real soon." Meanwhile, David Ray Griffin, another leading conspiracist, says the raid story "sounds fishy" because Bin Laden's body was buried at sea before it could be positively identified to Griffin's satisfaction. And so it goes. The decade since 9/11 has given rise to a panoply of conspiracy theories accusing the government of complicity in the attacks. These theories remained on the fringes of political life in the first few years after 9/11, grew in popularity with the unpopularity of Bush and the war in Iraq in the middle of the decade, and faded with the end of the Bush administration. But they have not died completely. As long as there is public distrust of governmentand with the financial crisis, the collapse of the economy, and the recent debt ceiling debate, public opinion of Washington is at a record lowthere will be conspiracy theories.

More specifically, there will probably always be 9/11 conspiracy theories. "I think that it was inevitable that a conspiracy, maybe many conspiracy theories, would arise, because inordinate tragedy is almost always accompanied by such conspiracies," says Lawrence Wright, whose Pulitzer Prize winning Looming Tower is the definitive account of the rise of al-Qaida. "People have a view of the world and they want to make the facts conform to that view." *** Professional conspiracists like radio host Alex Jones and Ruppert preached conspiracy theories for years before 2001. But for many "truthers," as they would call themselves, the 9/11 conspiracy was a kind of gateway drug. Most of the leading activists I spoke with became involved in the movement because of the Iraq war, but their anger at the Bush administration soon spread to all major institutions of government and media. "In order to maintain the bubble of the conspiracy, it needs to get more demonic, and it needs to include more people," explains

9/11 conspiracy apostate Charlie Veitch. "You need more and more evil until you hit the wall of absurdity." The theory that Veitch gave the most credence to was that there was an ancient order of freemasons, or illuminati, or an extremely rich central banking family that had been in control of all world events since the time of Babylon. According to this theory, 9/11 was a propaganda spectacle orchestrated to make the common man fearful. "There's something about it which appeals to the ego in people," Veitch said. "You suddenly feel empowered by having secret knowledge." A more typical theory about who is behind world events like 9/11, espoused by Alex Jones, is that a hodgepodge of disparate banking, corporate, globalization, and military interests are working together to bring about a New World Order of centralized "globalist" government. Jones' "world government" bogeyman has been around for decades. In his quintessential essay on the psychology of paranoia in American political life, The Paranoid Style in American Politics, Richard Hofstadter describes an episode from 1964: Shortly after the assassination of President Kennedy, a great deal of publicity was given to a bill, sponsored chiefly by Senator Thomas E. Dodd of Connecticut, to tighten federal controls over the sale of firearms through the mail. When hearings were being held on the measure, three men drove 2,500 miles to Washington from Bagdad, Arizona, to testify against it. Now there are arguments against the Dodd bill which, however unpersuasive one may find them, have the color of conventional political reasoning. But one of the Arizonans opposed it with what might be considered representative paranoid arguments, insisting that it was "a further attempt by a subversive power to make us part of one world socialistic government" and that it threatened to "create chaos" that would help "our enemies" to seize power. In the case of 9/11, Bush's policies in Iraq and the administration's guardedness with the 9/11 Commission helped create conditions that allowed the conspiracy theory to get a hearing. But the conspiracy theory was always going to exist. "Like in the case of the Kennedy assassination, [when] you have a horrible tragedy that seems absurd and it's hard to account for the fact that a single individual could inflict so much grief on the nation, there's a natural tendency to believe that there must be more at work," says Lawrence Wright. "In the case of 9/11 there was a sense of disbelief that a man in a cave in Afghanistan could reach out and humiliate the most powerful nation in the history of the world. How could that happen? It must be that something else was at work and because we are so powerful, we must have done it to ourselves." When Wright was touring the country with his book, he would regularly be confronted by conspiracy theorists who hadn't read the book but thought that, through clever questioning, they could demolish a case he had arrived at by five years of research and interviews with 600 sources. "I spent a lot of time trying to reason with various people who had these kinds of perspectives. And it was very frustrating," he said. "There was absolutely no way to argue with them because they rejected any kind of factual evidence."

After his book came out, Wright had occasion to discuss the alternative view of 9/11 with Alex Jones. Both men live in Austin, and both are friends with director Richard Linklater, who featured Jones as a street prophet in two of his films, A Scanner Darkly and Waking Life. During a party at Linklater's home near the Lost Pines of East Central Texas, the Slacker director put these two avatars of opposing 9/11 thought together. The conversation was similar to others Wright had had with other conspiracy theorists. "What they call facts aren't typically facts," Wright said. "They sound like facts. They're asserted. But basically, at the root of the conspiracies are these unproven theories." *** While the 9/11 conspiracy theory is based on conjecture, it has a stubbornness. The overall number of conspiracy believers has dipped since Bush left office, but the numbers believing the most radical version of the theory have been fairly steady. In 2006, 16 percent of respondents in a Scripps-Howard poll said it was either somewhat or very likely that the collapse of the Twin Towers was aided by explosives secretly planted in the buildings. That number was virtually unchanged in an Angus Reid Public Opinion poll this month. This was despite a 12 percent drop between 2007 and 2009 in the number of respondents who agreed with the statement that the Bush administration let the attacks take place in order to go to war in the Middle East. And although overall faith in the theories has subsided, general doubts about some kind of government cover-up have not. In the most recent Angus Reid survey, 66 percent of respondents said they believed the official version of events as presented by the 9/11 Commission, while only 12 percent did not. But 22 percent were undecided. Veitch compared being a believer in the theory to being in a cult. "There's so many people with so much of a vested political and psychological interest in maintaining, what I call the 'Conspiranoia,' view of the worldthat there are these demons just behind the scenes where we can't see, running everything," Veitch told conspiracy theorist Max Igan. Veitch is one of the rare cases of a conspiracy theorist going back on his views. Sites like 911myths.com, debunking911.com, and Screw Loose Change provide a valuable service in offering answers to rebut conspiracy theories. Conspiracy theories are "a little like sexually transmitted diseases," says Wright. "You have to take precautions and know that it's always going to be out there, but you should never succumb to the theories without actually thinking them through. I'm really dismayed to see very intelligent people often times taken in by what are really very absurd propositions." Which brings me back to the college friend who introduced me to a 9/11 conspiracy theory just one day after 9/11. I caught up with him last month, finding him the same bright, politically minded person I remembered. When we spoke on the phone, he remembered our conversation from 10 years ago as clearly as I did. And he was still convinced that he had been right to argue the point, even while acknowledging that the facts had proved him wrong. To him, there are always good reasons to be skeptical of any government version of events. This lack of faith in the government epitomized by the conspiratorial worldview has only become more widespread in the last 10 years. While the theories that Bush let 9/11 happen

intentionally were slowly dissipating in popularity on the left, they were replaced by the growth of "birther" theories on the right holding that President Obama was not a natural born American citizen, nor a legal president. The birther theory peaked in April when one in four Americans and 45 percent of Republicans told pollsters that they believed Obama was not born in the United States. Unlike the "truther" theories, the birther theory actually declined precipitously in the face of refutation. Still, it shows that a large portion of the American public, on both ends of the political spectrum, is capable of telling pollsters it agrees with irrational conspiracy theories. One likely explanation for this trend may be the record numbers of Democrats and Republicans who say they distrust the government. According to a Fox poll in July, the number of people who said they generally did not trust the government was at an all-time high of 62 percent, double what it was in June 2002. The number was highest among Republicans, with 76 percent saying they did not trust the government, but a plurality of Democrats also said they distrusted the government, as did 68 percent of independents. Nobody understands this distrust better than the conspiracy theorists themselves. That distrust is what has allowed these theories to gain credence on such a wide scale. Their viability has more to do with pessimism, anger, distrust, or some other psychological or emotional need than with evidence or even paranoia. These desires are universal, as evidenced by the popularity of 9/11 conspiracy theories in the Middle East. "One of the things I find particularly sad is that the conspiracy theorists in the U.S. have augmented this tendency in the Middle East to deny any cultural responsibility," Wright says. Jamal Khalifa, a source in The Looming Tower who Wright became friends with during the book's writing, was Osama Bin Laden's brother-in-law and his closest friend before Bin Laden founded al-Qaida. In the wake of 9/11, Wright says, Khalifa had a hard time accepting any kind of cultural blame as a Saudi for the attacks. And then he did. But toward the end of his life Khalifa was assassinated in Madagascar in 2007he began to doubt again. "He'd been watching things like Loose Change and so-on," Wright said. "He thought, 'well, why should I accept any responsibility. Americans are saying they did it themselves.' " "I remember being incredibly dismayed that he had changed his mind and especially why he had changed his mind," Wright recalls. "Middle Easterners are so susceptible to conspiracy theories, but it seems that Americans aren't much better."

You might also like

- 911 InsidejobDocument75 pages911 InsidejobCraig Darryl Skull PeadeNo ratings yet

- Was 911 MossadDocument8 pagesWas 911 MossadThorsteinn ThorsteinssonNo ratings yet

- The 9/11 Mystery Plane: And the Vanishing of AmericaFrom EverandThe 9/11 Mystery Plane: And the Vanishing of AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- 911 HoaxDocument34 pages911 HoaxDasNo ratings yet

- The Deep State: How an Army of Bureaucrats Protected Barack Obama and Is Working to Destroy the Trump Agenda by Jason Chaffetz | Conversation StartersFrom EverandThe Deep State: How an Army of Bureaucrats Protected Barack Obama and Is Working to Destroy the Trump Agenda by Jason Chaffetz | Conversation StartersNo ratings yet

- PDF About 9/11 CommissionDocument24 pagesPDF About 9/11 CommissionWilliam Giltner100% (2)

- Russia Has Presented Evidence Against US, UK and Israel As Being The Actual 911 TerroristDocument15 pagesRussia Has Presented Evidence Against US, UK and Israel As Being The Actual 911 TerroristAbdul Haadi Butt100% (1)

- Exposing the Russia Hoax: How the Deep State Conspired to Frame a Sitting PresidentFrom EverandExposing the Russia Hoax: How the Deep State Conspired to Frame a Sitting PresidentNo ratings yet

- 9/11 UnveiledDocument84 pages9/11 UnveiledNoel Jameel Abdullah80% (5)

- 911 Crash Test 911 PLANES HOAXDocument95 pages911 Crash Test 911 PLANES HOAXpanikos20040% (1)

- 10 Solid Facts About 9-11Document5 pages10 Solid Facts About 9-11scriberoneNo ratings yet

- All The Proof You Need.Document42 pagesAll The Proof You Need.escanquema100% (1)

- 9 - 11 Insider Trading Who Made Money From The WTC and Pentagon TragediesDocument3 pages9 - 11 Insider Trading Who Made Money From The WTC and Pentagon TragediesAnonymous yjwN5VAjNo ratings yet

- The Twin Towers Tragedy: A Look at the 9/11 Terrorist AttacksDocument51 pagesThe Twin Towers Tragedy: A Look at the 9/11 Terrorist AttacksYamilNo ratings yet

- 911 Israel's Grand DeceptionDocument14 pages911 Israel's Grand DeceptionJohn Pierce100% (1)

- The Truth Israel Did 11th Sept 2001 AttacksDocument104 pagesThe Truth Israel Did 11th Sept 2001 AttacksLloyd T Vance0% (1)

- 9 11 EvidenceDocument10 pages9 11 EvidenceHafsa HafsaNo ratings yet

- Behind The Smoke CurtainDocument198 pagesBehind The Smoke CurtainDizietSma100% (2)

- Timeline of Zionist False Flag Terror and DeceptionsDocument14 pagesTimeline of Zionist False Flag Terror and DeceptionsVictoriaGilad100% (3)

- The Latest on the Greatest: The False Flag Operation of 9/11 and BeyondDocument229 pagesThe Latest on the Greatest: The False Flag Operation of 9/11 and BeyondniNo ratings yet

- JFK Assassination Conspiracy TheoriesDocument5 pagesJFK Assassination Conspiracy Theoriesapi-500738459No ratings yet

- 911 Story 9-14Document37 pages911 Story 9-14api-63155250No ratings yet

- Sandy Hook - Huge Hoax and Anti-Gun "Psy Op" - Veterans TodayDocument13 pagesSandy Hook - Huge Hoax and Anti-Gun "Psy Op" - Veterans TodayGordon Logan67% (9)

- Boston Marathon Bombing Hoax ExposedDocument29 pagesBoston Marathon Bombing Hoax ExposedScott Odam100% (1)

- The Sandy Hook Elementary School Shooting Hoax Is Now A Verified CrimeDocument18 pagesThe Sandy Hook Elementary School Shooting Hoax Is Now A Verified Crimetired_of_corruption50% (2)

- The Seven Seals 5Document7 pagesThe Seven Seals 5api-3711938No ratings yet

- The REAL Obama An INDONESIAN, Muslim, Socialist PuppetDocument8 pagesThe REAL Obama An INDONESIAN, Muslim, Socialist PuppetMoBique50% (2)

- The 9/11 Commission Report: Omissions and Distortions by Dr. David Ray GriffinDocument115 pagesThe 9/11 Commission Report: Omissions and Distortions by Dr. David Ray GriffinQuickSpin92% (13)

- September Conspiracy: Valeska Lira Catalina Marín Pía Marín Daniela Valenzuela Javiera VallejosDocument10 pagesSeptember Conspiracy: Valeska Lira Catalina Marín Pía Marín Daniela Valenzuela Javiera VallejosCatalina Marín AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Conspiracy TheoriesDocument1 pageConspiracy TheoriesYourGoddessNo ratings yet

- CIA COLUMBIA OBAMA Sedition and Treason TRIAL-PRESS RELEASE 27oct2010Document11 pagesCIA COLUMBIA OBAMA Sedition and Treason TRIAL-PRESS RELEASE 27oct2010Neil B. Turner0% (2)

- Erasing 9:11 Truth: VT Restores One Key Evidentiary Piece - Veterans Today - Military Foreign AffairDocument13 pagesErasing 9:11 Truth: VT Restores One Key Evidentiary Piece - Veterans Today - Military Foreign AffairmkultNo ratings yet

- SpyGate 101: A Primer On The Russia Collusion Hoax's Years-Long Plot To Take Down TrumpDocument8 pagesSpyGate 101: A Primer On The Russia Collusion Hoax's Years-Long Plot To Take Down TrumpBursebladesNo ratings yet

- Articles On Conspiracies, 9/11, Prophecy, The Illuminati, and The NWO.Document30 pagesArticles On Conspiracies, 9/11, Prophecy, The Illuminati, and The NWO.Jerry SmithNo ratings yet

- Clinton Body Count-5 PDFDocument5 pagesClinton Body Count-5 PDFKeith Knight100% (2)

- The Top 40 Reasons To Doubt The Official Story About 9-11Document15 pagesThe Top 40 Reasons To Doubt The Official Story About 9-11api-3747231100% (1)

- 9-11 by Robert SteeleDocument101 pages9-11 by Robert Steeletoski_tech5051100% (3)

- The Underground 911 ReportDocument70 pagesThe Underground 911 ReportinnocentbystanderNo ratings yet

- Sandy Hook Truth Shadow Banned On TwitterDocument107 pagesSandy Hook Truth Shadow Banned On Twittertired_of_corruption0% (1)

- 9-11 Truth MovementDocument13 pages9-11 Truth MovementRizky Muhammad Faris PrakosoNo ratings yet

- The 9-11 Deception & False Flag TerrorDocument222 pagesThe 9-11 Deception & False Flag TerrorTerence Smart57% (7)

- T7 B16 Flight 11 Gun Story FDR - Zelikow Facts V Fiction Email - Notes (Paperclipped - See Alt Version T7 B7)Document18 pagesT7 B16 Flight 11 Gun Story FDR - Zelikow Facts V Fiction Email - Notes (Paperclipped - See Alt Version T7 B7)9/11 Document ArchiveNo ratings yet

- Voices Rowland MorganDocument321 pagesVoices Rowland Morgananthonyjthorne1379100% (1)

- Lynne Cheney's 9/11 Notes From The White House BunkerDocument6 pagesLynne Cheney's 9/11 Notes From The White House Bunker9/11 Document Archive100% (1)

- 911 UnveiledDocument84 pages911 UnveiledJulius Gbenga Abiodun100% (1)

- The Truth About Osama Bin Laden PDFDocument42 pagesThe Truth About Osama Bin Laden PDFLloyd T Vance100% (2)

- False Flag OpsDocument15 pagesFalse Flag OpsTheDetailer100% (4)

- 9 - 11 Links PDFDocument118 pages9 - 11 Links PDFjoelyNo ratings yet

- Duke, DavidDocument19 pagesDuke, DavidfutarouNo ratings yet

- Sandy Hook: Fleecing The SheepleDocument6 pagesSandy Hook: Fleecing The SheepleGordon Duff40% (5)

- American HolocaustDocument134 pagesAmerican HolocaustEditor 1100% (2)

- 11 Sept. 2001Document58 pages11 Sept. 2001Tatiana StanciuNo ratings yet

- The Truth About 11th Sept 2001 AttacksDocument70 pagesThe Truth About 11th Sept 2001 AttacksLloyd T Vance100% (1)

- Insider Trading 911..unresolved, by Lars SchallDocument36 pagesInsider Trading 911..unresolved, by Lars Schalljkim3334270100% (2)