Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Methamphetamine Use in Japan After The Second World War: Transformation of Narratives

Uploaded by

Amy LewisOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Methamphetamine Use in Japan After The Second World War: Transformation of Narratives

Uploaded by

Amy LewisCopyright:

Available Formats

Contemporary Drug Problems 35/Winter 2008

717

Methamphetamine use in Japan after the Second World War: Transformation of narratives

BY AKIHIKO SATO

Scholars have argued that post-World War II domestic disorder in Japan caused a serious methamphetamine problem, which directly led to the establishment of the Stimulant Control Law of 1951. This paper examines the process through which that Law came into effect to argue the central significance of shifting discourses surrounding methamphetamine use, especially by users themselves, and nationalist dialogue concerning secret production and the smuggling of methamphetamine. These factors worked together in the 1950s to transform contemporary understandings of methamphetamine use, and to foster state efforts to regulate it.

AUTHORS NOTE: I express my gratitude to Professor David T. Courtwright

of the University of North Florida, who recommended me to present part of my book Drug and Discourse: Methamphetamine in Japan to the Global Approaches conference; to Dr. Kyoko Murakami of University of Bath, a specialist in discouse analysis, who commented on the first draft of this article; and to Dr. Norman Smith of University of Guelph (Canada), who encouraged me to write in English.

2009 by Federal Legal Publications, Inc.

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

718

METHAMPHETAMINE USE IN JAPAN AFTER WWII

Methamphetamine, popularly known as ice or crystal in the streets of Western countries today, was discovered in Japan in 1888.1 It was initially named M33N because it was the 33rd extract discovered by Nagayoshi Nagai (1845-1929) of Tokyo University in the course of his analysis of Maou (ephedrae herba). Nagai had worked as an assistant to August Wilhelm von Hofmann of Humboldt-Universitt zu Berlin before returning to Japan in 1884 in order to construct modern (i.e., Westernized) pharmaceutics (Nagai, 1893; Kanao, 1960; Yamashita, 1966, 1969). He was known for his research on Maou extract, and especially for the discovery of ephedrine in 1885. However, M33N sank into oblivion until the 1940s, when researchers argued that it might have medicinal applications (Horimi, Hashimoto, Inour, Soya & Egawa, 1940; Ariyama, 1941; Miura, 1941). In 1941 Kinnosuke Miura, a methamphetamine expert, wrote: The reason why I publish this research . . . is because I have read the article about the applications of Pervitin by P. Pllen, and find that it is suitable at this time to produce a medicine as useful as Pervitin in our country and make it available for our colleagues (Miura, 1941, p. 8). Pervitin was the name given to methamphetamine in Germany. Other researchers, Taro Horimi of Osaka University and Noboru Ariyama of Niigata Medical College, also referred to the useful features of methamphetamine and amphetamine, 2 as described in medical and pharmaceutical journals in Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States, where amphetamine was already commercialized by the 1930s. The reason why methamphetamine was re-evaluated and reintroduced in Japan was because of these Western precedents. Methamphetamine and amphetamine were then made available for commercial use in Japan; they were initially used in hospitals and by students for night-time study. However, as the phrase it is suitable at this time in the Miura quotation cited above suggests, methamphetamine was soon used in mil-

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

719

itary and related organizations after the start of the Pacific War in December 1941. Following Japans defeat, methamphetamine (and amphetamine as well) began to be used throughout Japan, especially in the urban areas, the users including novelists, dancers, and night-club comedians as well as ordinary office workers. However, it was soon demonized as a drug that was thought to produce addiction and psychosis. Why did such an abrupt change happen in Japan? And how? Some typical answers to these questions have been provided by medical doctors and criminologists (Tatetsu, Goto, & Fujiwara, 1956; Tamura, 1982; Suwaki, Fukui, & Komura, 1997). They argue that Japan had a recognizable methamphetamine problem immediately after the Second World War, when postwar disorder induced many people to use methamphetamine as a way of relieving mental stress and depression. This produced high numbers of methamphetamine psychosis, and subsequently the Stimulant Control Law of 1951 was established in response. The problem with this argument, however, is that many people continued to use methamphetamine regularly without developing psychosis, and, besides, there was no mention of the psychosis-producing effect of methamphetamine in the National Diet debate on the Stimulant Control Law. This article seeks to explain methamphetamine use in postwar Japan by describing the steps that led to the passage of the Stimulant Control Law and by analyzing contemporary narratives on methamphetamine and its use, especially in reference to two elements of the story that have not been previously discussed: transformations in the discourse of methamphetamine use, especially by users themselves, and nationalist dialogue concerning the secret production and smuggling of methamphetamine. Both are particularly relevant to post-war Japan, especially in the 1950s. Narrative analysis requires a distinct perspective. The narratives analyzed here will not be used as evidence of contemporary facts. Rather, they will be treated as factual accounts that

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

720

METHAMPHETAMINE USE IN JAPAN AFTER WWII

construct versions of variant realities. In other words, each narrative has the potential to realize what it implies, and those potentialities suggest the many possibilities of narratives with regard to the same thing. The questions above might be rephrased as follows: Why and how did some narratives come to dominate others, and what caused the abrupt change in the formation of narratives on methamphetamine in Japan in the 1950s? Methamphetamine use and condemnation Methamphetamine, once made available for commercial use in the 1940s by many pharmaceutical companies, was more popular than amphetamine. This is illustrated in Figure 1, below. One of the most famous and popular medicines was Philopon, which was extracted by Dr. Miura and the Dainippon Pharmaceutical Company and made available in 1941. Philopon is a coined word, combining the Greek philo (love) and ponos (labor), and was a synonym for stimulants until the 1970s.3 The Imperial Japanese Armed Forces used methamphetamine during the Second World War. For example, soldiers on sentry duty were supplied with tablets called Cat-Eye Tablet (Nekome-Jo). Most famously, it was used by the Special Forces, such as the kamikaze. The tablets for the Special Forces were blended with green tea powder, stamped with the emperors crest, and named The Storming Tablet (TotsugekiJo or Tokkou-Jo). After the war, the Armed Forces stockpiles of these medicines were dispersed through channels that are impossible to trace because of post-war disorder.4 However, elderly veterans have told the author that, once the war was over, they took their medicines home and used them as a way of staying awake while studying or working through the night. They claim that the medicines were very useful and did not cause

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

721

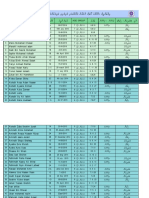

FIGURE 1

Patented medicines containing methamphetamine and amphetamine in the 1940s (Ikuta, 1951)

Patent Name Hospitan Takarapin Neopampron Methypamine Hinodedorine Neopamine Supermine Kobapon Methypron Fukuzedrin Neophilon Philopon Proamine Zedrin Aron Hospitan Agotine Neoagotine (Actamine) Propamine Okapron Methypron Parten Zandorman Company Santendo Pharmaceutical Company Takara Pharmaceutical Company Ono Pharmaceutical Company Manwa Pharmaceutical Company Hinode Chemical Company Toho Sangyo Corporation Nissin Chemical Corporation Kobayashi Pharmaceutical Industries Company Yodogawa Pharmaceutical Company Touzai Pharmacy Nitto Pharmaceutical and Chemical Industries Company Dainippon Pharmaceutical Company Ueno Fine Chemical Industry Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Shizuoka Caffeine Company Mita Pharmaceutical Company Toyama Chemical Company Toyama Chemical Company Naigai Seiyaku Company Okano Pharmaceutical Company Shiraimatsu Pharmaceutical Industries Company Shionogi and Company Doujin Pharmaceutical Company Content methamphetamine methamphetamine methamphetamine methamphetamine methamphetamine methamphetamine methamphetamine methamphetamine methamphetamine methamphetamine methamphetamine methamphetamine methamphetamine methamphetamine amphetamine methamphetamine methamphetamine amphetamine methamphetamine methamphetamine methamphetamine methamphetamine amphetamine amphetamine

Methylpropamine Taisho Pharmaceutical Company

any harm. They also expressed surprise upon being told that the medicines were stimulants which have been thought to produce addiction and even psychosis.5 Faulty memories may be at work here, making it difficult to assess the veracity of

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

722

METHAMPHETAMINE USE IN JAPAN AFTER WWII

the facts these veterans relate, especially as they pertain to methamphetamine. Nevertheless, their recollections are highly suggestive of the ways in which people viewed such medicines in the early post-war period. The fact that they did not associate the medicines with ill effects might astonish readers today because narratives concerning methamphetamine have altered so thoroughly that the positive features of these drugs are rarely discussed. Documentary evidence from the post-war period supports the veterans testimony. One prominent example can be found in the minutes of the National Diet for November 24, 1949. The Ministry of Health and Welfare (the current Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare) had issued administrative guidelines (in other words orders, even though they had no legal basis) and regulations to every pharmaceutical company to refrain from the production of methamphetamine and amphetamine, on the ground that some users, such as novelists, performers, and students, were said to abuse them. 6 However, Yuzo Ogawa, a representative of the Diet, called such administrative measures into question. I have some questions about the Philopon problem, he said. The Ministry of Health and Welfare, in the name of the undersecretary, asked every pharmaceutical company not to produce or to reduce the amount of production of Philopon and other stimulants. But the general working public and the industry as well have been suffering from such measures. According to medical and pharmaceutical points of view, the stimulants represented by Philopon are excellent medicines (National Diet, 1949, p. 1116). He added that the problems associated with Philopon were confined to a small group of users and that it would be better to enforce strict control over those abusers rather than over the entire population. Ogawas comments indicate that in the late 1940s people could still discuss the positive effects of methamphetamine even after it was claimed to be dangerous or at least problematic. Since positive narratives regarding methamphetamine

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

723

use remained in circulation, we can understand why Ogawa pleaded against the ministrys measures, arguing that methamphetamine was abused only by certain individuals.7 In other words, whatever problems were associated with methamphetamine should be attributed not to the medicine itself but to the specific groups or persons who abused it.8 On the other hand, the ministry had good reasons for taking the action it did. Two high-profile deaths had already contributed toward Philopons reputation as a dangerous drug. On October 14, 1946 Miss Wakana (Kikuno Kawamoto, 1910-1946), a famous comedienne, died from a heart attack suffered on the platform of the Nishinomiya Kitaguchi station near Kobe. Since she was known to have used Philopon regularly, her death was interpreted to have been caused by its use (Iwata, 1947). Then, on December 4, 1947, Sakunosuke Oda (1913-1948), a popular novelist, spat blood and entered Tokyo Hospital. He died on January 10, 1948. He was also well known for using Philopon, so many people thought that he died because of it.9 Incidents such as these led some people to condemn the use of Philopon and other stimulants. By 1949, significant condemnation of methamphetamine, or, to be more exact, its users, especially writers and performers, arose. For example, Imao Hirano, a poet and a scholar of French literature, writing in the monthly magazine Sekai Hyouron (World View), criticized the use of Philopon in the post-war literature movement (Hirano, 1949). He recounted that he had met a demonic man during the war who sold Philopon even though he was well aware of its effects on young kamikaze. Hirano argued that Philopon was a symbol of the darkness of wartime and attacked the post-war literature movement for ignoring this fact and thereby encouraging a mindset not worthy of the post-war era. His essay is but one example of contemporary condemnation of methamphetamine users, especially artists who were looked down upon as immoral (Suzuki, 1949; Takeyama, 1949).

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

724

METHAMPHETAMINE USE IN JAPAN AFTER WWII

Methamphetamine, therefore, was initially condemned not for its intrinsic features but for its symbolic meaning and for its association with users who were perceived to be deviants. However, such views were not so powerful as to win support for any law aimed at directly prohibiting or at least controlling the use of methamphetamine and amphetamine. The National Diet did not take any action along these lines. Rather, the ministry applied administrative guidelines and regulations to control the amount of production in order to prevent specific groups and persons from abusing the drug. In order to establish laws for methamphetamine control, more problematic aspects of the issue needed to arise. The stimulant control law The process of the legalization of methamphetamine control reflects how contemporaries viewed methamphetamine. In the National Diet, the first debate on methamphetamine use occurred in October 1949. Diet minutes demonstrate that the first step in calling methamphetamine into question related to circumstances around street children, most of whom had lost their parents in the war because of methamphetamine use. The following is an exchange between two Diet representatives:

Ms. Natsue Inoue: Now look, what I want to discuss is a problem about street children using Philopon that has been discussed in the newspapers.10 If there are any documents about it, I would like to get them. Or, if there seems to be discussion regarding control over narcotics these days, then Ill ask the chair of the committee to do something, to invite some government officials related to things like that. Chair (Mr. Juzo Tsukamoto): I have also been thinking of these important problems so I visited the Ministry of Health and Welfare, where I heard something from the Pharmaceutical Affairs Bureau and met the Chief of the Bureau to talk about it. He insisted that the Ministry was also anxious about the situation. He also mentioned that there were some committees for such matters. I think we will discuss this issue in another session. (National Diet, 1949, October 24, p. 6)

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

725

Subsequently, the Ministry of Health and Welfare sent administrative guidelines to every pharmaceutical company suggesting a production quota. As the discussions went on in the Diet, it became clear that the representatives and government staff shared the opinion that those who were to be blamed were not the street children using methamphetamine but the smugglers and other adults who gave methamphetamine to them. These people made the street children abuse it, and some of them encouraged the children to steal in exchange for methamphetamine, so that the children were thought to be victims in that sense as well (National Diet, 24 Oct. 1949; Asahi Shinbun, 1949, 19 Oct., 24 Oct., 22 Nov.). In fact, street children often needed something to keep their energy level high, since food was still being rationed and its distribution was often behind schedule.11 Yet, while the Diet and the Ministry of Health and Welfare paid attention to Philopon abuse in the streets, many people still used methamphetamine regularly. An editorial titled Where Does Philopon Go? (Philopon wa Dounaru?) in the Journal of the Japan Medical Association (Nihon Ishikai Zasshi) in 1950 stated:

Recently there is a decline in news about the addiction to Philopon and other stimulants, whereas it was once a considerable topic of news and conversation, even the National Diet discussing it. Because the main consumers of the medicine are media stars like popular novelists, actors, singers, prostitutes, rascals in the streets, and street children, the news was often exaggerated. Supposedly the use of the medicine has spread over all social classes. When I met many journalists in a meeting and asked them about its use, I was very surprised to find that almost all of them have been using it regularly. Of course, they suggested that its use is not due to addiction but to the need to make work productivity rise. They excused it as follows, If the companies pay well, we do not need to work until late at night and to use such stuff. One of the reasons for the prevalence of this medicine is seriously damaged social circumstances, that is to say, the poverty of post-war society and the lack of wholesome amusements and non-essential grocery items. (Japan Medical Association, 1950, p. 141)

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

726

METHAMPHETAMINE USE IN JAPAN AFTER WWII

An incident involving Toyama Chemical (Toyama Kagaku Kougyou) was one of the triggers for the legalization of methamphetamine control (Kondo, 1955). In October 1950 approximately 100 young people (men and women) were arrested in connection with what was called a Mass Sexual Assault Incident in Tsuchiai Village (Tsuchiai Mura, absorbed into Urawa City in 1955).12 Then it was brought to light that many of those arrested used Neoagotine (methamphetamine), produced by Toyama Chemical (see Figure 1). It was also revealed that Toyama Chemical produced over 10 million ampoules quarterly, whereas its production quota was only 51,000. However, the quota had no legal basis because it was just an administrative guideline, so that Toyama Chemical was fined only 5,000 yen (about 14 US dollars) for not reporting accurate production totals (National Council of Youth Problems, 1950; Asahi Shinbun, 1950, 10 Nov., 13 Nov., 15 Nov.).13 The National Police Headquarters and other official bodies stressed the need for laws to provide strict control of such activities.14 The issue of methamphetamine control was thus promoted on the basis that those to be blamed were the smugglers and people producing methamphetamine secretly. Two psychopathologists were called to the Diet to testify about what later came to be identified as the negative features of methamphetamine use, notably addiction and psychosis (National Diet, 1951, February 15) Still, the first purpose of methamphetamine control was not to punish users but to maintain strict control over smugglers (National Diet, 1951, February 22). Thus, government staff explained the clause prohibiting the possession of the stimulant as follows:

Clause number 14 prohibits possession. One of the most difficult matters that official control bodies have to deal with is the lack of a legal basis to control possession. They cannot prosecute those who possess stimulants to sell in the town like Ueno.15 The Pharmaceutical Affairs Law is only for the companies and persons who manufacture and deal in medicine by occupation. So the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law cannot be administered to those who just possess stimulant. Even if a person possesses stimulants to sell, s/he cannot be

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

727

arrested unless the crime is committed in the presence of an officer. (National Diet, 1951, May 23, pp. 14-15)

The Stimulant Control Law was passed in June 1951. It prohibited possession of the drug; however, as noted above, the clause containing this provision was designed to arrest smugglers, who often insisted that their drugs were just for their personal use and not for sale (National Diet, 1951, 25 May). New narratives The process whereby the Stimulant Control Law of 1951 came into being was driven by factors quite different from the conventional understanding of methamphetamine today, namely, that methamphetamine is a drug that often causes addiction and psychosis. In the early 1950s people could still talk about its positive values, even in public places such as the National Diet of Japan. And so, to understand how the perception of methamphetamine changed, we need to look at another process whereby new narratives on methamphetamine emerged following the passage of the 1951 law, and especially after 1954 when a campaign for the eradication of methamphetamine was launched. At this point, narratives on methamphetamine use began to converge into a new pattern, triggered in part by a famous homicide case. On April 20, 1954 an 11-year-old schoolgirl, Kyoko Hosoda, was sexually assaulted and murdered in the restroom of the primary school in the Bunkyo district of Tokyo. She had gone to the restroom during a class and never returned. The teacher did not notice her absence until her mother, who was visiting the school, asked where her daughter was. A school-wide search ensued; finally, her mother found her body in the restroom. The case was called the Kyoko-chan incident, after the victim (Kyoko-chan Jiken). The shock in the community was such that newspapers covered the investigation almost every day until May 6, when the suspect was arrested. In all, 667 people were questioned during that period.

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

728

METHAMPHETAMINE USE IN JAPAN AFTER WWII

At the beginning, and sometimes later as well, the girls murder was attributed to the teachers carelessness (National Diet, 1954, April 20, May 14). However, when the suspect, a 20-year-old man named Shukichi Sakamaki, who had been suffering from tuberculosis and used Philopon, was arrested, a new interpretation aroseone that underlines the role of newspapers in symbolically demonstrating the transformation of methamphetamine narratives. The newspaper Asahi Shinbun reported on May 6, just after the arrest, the suspects version of events. While walking by the school, he said, he had decided to use its restroom. One of the stall doors was open slightly, revealing the foot of a girl. With the intention of raping her, he entered the stall and locked the door. The girls screams as he assaulted her caused him to lose control, and he strangled her. He was now sorry for what he had done; in fact, the arresting officer related that Sakamaki had cried during his interrogation. The article also reported that Sakamaki had committed other sexual misconduct since he was teenager. In another newspaper article, Sakamakis father said that, while he had been sweet-tempered when very young, his character changed for the worse when his mother began occasionally cohabiting with her lover in Sakamakis lodging (Asahi Shinbun, 1954, May 6). Most of the reports attributed his murder of Kyoko Hosoda to his warped personality, as well as the environment in which he grew up. However, on May 7, 1954, Asahi Shinbun introduced a new theme: methamphetamine use was one of the main causes of the incident, far more important than personality and environment. An article headlined There Still Exists Another Sakamaki, Kyoko-chan Incident Tells Us (Mada Iru Dai Ni no Sakamaki, Kyoko-chan Jiken wa Oshieru) reported the view of a psychopathologist, who had testified to the fatal features of methamphetamine in the Diet in 1951, that Sakamakis behavior was typical of that of Philopon addicts.16 The article denounced Philopon and stressed the importance of eradicat-

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

729

ing it (Asahi Shinbun, 1954, May 7). And on May 8, the newspaper argued strongly in an editorial that stimulants made young people lose their reason and commit crimes, often psychopathic, and that the eradication of stimulants was urgently needed. The popular notion that many brutal crimes were caused by methamphetamine psychosis and that the problem was methamphetamine itself can be seen in the strong movement against the drug in 1954. That June, the Stimulant Control Law was amended to impose heavier punishments for violations of the law,17 and in October the government launched a campaign for the drugs total eradication. This campaign resulted in significant numbers of arrests: 55,664 in 1954, the largest number in the history of the Stimulant Control Law (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Number of arrests for violation of Stimulant Control Law (from White Papers)

60,000

50,000

40,000

Population

30,000

20,000

10,000

19

The same association of brutal crimes with methamphetamine psychosis resulted in the transformation of narratives surrounding users. Starting in 1954, almost all the narratives by users that appeared in government documents, newspapers,

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

6 19 3 65 19 67 19 69 19 71 19 73 19 75 19 77 19 79 19 81 19 83 19 85 19 87 19 89 19 91 19 93 19 9 19 5 97 19 99 20 01 20 03 20 05

Year

19

19

19

19

19

19

51

53

55

57

59

61

730

METHAMPHETAMINE USE IN JAPAN AFTER WWII

and magazines were recast into a new and single pattern. Consider, for example, a magazine article that appeared in October 1954 entitled The Actual Conditions of the Terrible Illness [Philopon] That Disrupts Our Country: The Devil Taking Aim at Young Peoples Bodies (Osorubeki Boukoku Byou [Philopon] no Jittai: Seishounen wo nerau nikutai no akuma). Claiming that methamphetamine use by young people posed a threat to Japanese society, the author (an ex-user of Philopon) pointed to his own experience as evidence. He said that, under the influence of the drug, his hallucinations reached the point that he mistook a dustbin for a policeman and a dog for a detective. Now 19 years old and in a reformatory, he was convinced that his troubles were the result of methamphetamine use. His account read as follows:

I found good effects from Philopon after using it for studying for my exams. I escalated my use up to 50 ampoules per day one month later. Nothing felt better than when I injected the needle into my blood stream. I felt as if I were in Heaven when I cut the top of an ampoule for preparation. When I could not get any Philopon, I sometimes felt good only when I injected just a needle without it. I took my school uniform to a pawnshop to buy it. In the meantime, I could not stand without shooting 5 cc every hour. One night, when I suffered from withdrawal pain, I rushed like a sleepwalker to the Korean village where I often bought it. But I found a policeman (it was a dustbin) crouching to apprehend me. I was surprised to see him and tried to go by another route, but the policeman chased me. I ran like mad and then a detective (a dog) jumped out suddenly in my path. I cried and returned to my house. Even then, I could not help thinking that the policeman was coming to catch me whenever I heard a sound at the gate and the kitchen . . . I could not stop worrying, so I went upstairs and hid myself in the closet. I chattered because I could not help thinking that the electric cable at the stairs looked like the telephone line with which my family called the police . . . I now find it was like I was crazy, but I spent such terrifying days that everything I heard and saw was the stuff for chasing me and even killing me. (Anonymous, 1954, pp. 107-108)

There are several interesting themes in this narrative. When we consider the above example from a sociological point of view, it can be thought of as an account that performs a discursive action to justify or excuse ones action (Scott &

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

731

Lyman, 1968; Buttny, 1993). In addition, from an ethnomethodological perspective, accounting is one of the main activities of our ordinary life, which people use to render their actions normal, understandable, proper, and the like. People account for their actions so that others can make sense of what they are doing for all practical purposes (Garfinkel, 1967) in interactions. Against this background, we can view the testimony quoted above as an example in which the narrator explains his actions to make himself understandable to othersthat he is using methamphetamine intoxication as a discursive resource to make sense of his actions. In other words, the narrator is presenting his actions as ones that were caused not by his inborn personality but by his use of methamphetamine. Additionally and interestingly, the narrators account of hallucinations shows the gap between the period of intoxication (insane in the past) and the period of recovery (sane at present), and makes his story persuasive. The reason why he can now describe his past actions so clearly is that he has now noticed the fact (i.e., his version of reality) that he experienced hallucinations in the past. His awareness that the policeman was actually a dustbin and the detective actually a dog became possible only after he reached the realization that he had been intoxicated and suffering hallucination. This realization demonstrates that he has recovered. In short, he finally understands what he did while under the influence of methamphetamine, and he can now (when he is narrating) discuss it rationally because he has stopped using methamphetamine and recovered from intoxication. His narrative itself functions to show that he is now normal. To use the terminology of Harvey Sacks (1970), his narrative shows him doing being ordinary.18 This type of narrative, then, argued that blame for misdeeds was to be applied not to users themselves but to methamphetamine. It showed that users were aware of their past problems (which are typically expressed in doubled descriptions of past

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

732

METHAMPHETAMINE USE IN JAPAN AFTER WWII

and present, as in the example above), but that, in their view, it was not they themselves but the methamphetamine that was responsible for these problems. Negative features of methamphetamine were used as discursive resources to show that users were victimized, thereby allowing them to avoid responsibility for past actions and show that they are now normal. When examining examples of methamphetamine narratives after 1954, the following common features emerge:

Users began to use methamphetamine not because they wanted to, nor because they wanted to do bad things. They found themselves unable to stop using it. Their use of methamphetamine was accompanied by many ancillary troubles, such as hallucination and violence. They finally became aware that they had been intoxicated.

This type of narrative provides the standpoint from which Japanese policy on methamphetamine has been justified since 1954, and especially in the 1970s, during the second prevalence of stimulants (Sato, 2006: Chapter 8). In the 1970s, the government published a booklet entitled Terrors of the White Powder (Prime Ministers Office (1977)), in which the same narrative was repeated but with the following variation: users often express their gratitude to police for their arrest at the end. This theme occurs throughout the narratives cited in Terrors of the White Powder, which was based mainly on testimony collected during police investigations. The booklet was often cited in books and magazines (e.g., Shukan Sankei [1977]; Muroo [1982a, 1982b]), which presumably made the narratives even more popular. The widespread prevalence of the booklet does not mean that the government was involved in a sort of conspiracy to shape narratives in certain ways. Rather, people arrested for using stimulants, mainly methamphetamine, explained their actions in such a way as to make themselves understandable to others, in this case police officers.

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

733

The narrative of methamphetamine users had been transformed so thoroughly that users could never talk about their experiences in the same terms as they had before 1954, at least in public places. These historical and interactional dynamics reveal how the meanings of methamphetamine underwent such an abrupt change and how many people reached the conclusion that those who used methamphetamine inevitably became insane and could not recovera belief that most Japanese hold today.19 There is now a consensus, including among official drug-control organizations, that methamphetamine has such fatal features that no one can escape them once she or he starts using the drug. This may explain why no institution for rehabilitation had developed until the Drug Addiction Rehabilitation Center (DARC) was organized in 1985 in Tokyo.20 Nationalist talk There is another aspect of this story which also accounts for the changing narratives of methamphetamine. That is the belief, which in part drove the anti-methamphetamine campaign of 1954, that methamphetamine abuse was caused by hostile forces originating from outside Japan. The state of Japanese society during the occupation directly relates to transformations in methamphetamine narratives. After losing the war, Japan was occupied by the United States military and controlled by General Headquarters/Supreme Commander for Allied Powers (GHQ), under the leadership of General Douglas MacArthur. In 1949 the Peoples Republic of China was founded by the Chinese Communist Party, and in May of the following year MacArthur argued that the Japanese Communist Party should be made illegal. Over the next month, 24 members of the Central Committee of the Japanese Communist Party and some officers of the party journal were expelled from the public service. Subsequently,

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

734

METHAMPHETAMINE USE IN JAPAN AFTER WWII

when the Korean War (19501953) broke out on June 25, 1950, the menace of communism began to be talked about publicly. The GHQ ordered the government, mass media, and other companies to expel all communists, starting in July. Approximately eleven thousand people were expelled (National Diet, 1950, November 17), launching the Red Purge. The authorities also felt threatened by movements which were thought to be under communist control. On May Day, 1952, large anti-government demonstrations and marches were organized in several big cities and many people were arrested; 253 had been prosecuted by January 1953 (Asahi Shinbun, 1953, January 28). The most infamous demonstration happened in Tokyo, in the park in front of the Imperial Palace. That demonstration led to the arrest of 1,206 people and the prosecution of 236 (National Diet, 1953, July 17). A plenary session of the Diet and several of its committees discussed the unrest and concluded that communists and their sympathizers were responsible (National Diet, 1952, May 6, May 7, May 9). And later the government officially announced that the turbulence had been engineered by foreign communist countries (National Diet, 1952, July 1). In the years afterwards, the menace of communismparticularly as embodied by the communist state of North Korea and the illegal manufacture and smuggling of methamphetamine gradually became intertwined. The connection was not so clear in 1952, though one newspaper, Asahi Shinbun, hinted at it for the first time in August of that year (Asahi Shinbun, 1952, 25 Aug.). The article reported that two Japanese men had illegally produced methamphetamine in Tokyo and transported it to Korean neighborhoods in Kawasaki (next to Tokyo). It also noted, interestingly, that one of the offenders was an ex-communist. One year later, in August 1953, the connection between Koreans, communism, and methamphetamines was made more explicit: Much of the illegal production of Philopon was done by Korean people, who cannot live by selling clothes, moonshine, and cigarettes in the under-

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

735

ground markets lately. They have changed their source of income to the manufacture of Philopon, which is relatively easy to produce in a small place, as reported by the Metropolitan Police. They also argued that it is difficult to control them because there are strong forces that plead against control on the ground that it threatens peoples right to live (Asahi Shinbun, 1953, 17 Aug.). In this statement, the term some strong forces was meant to suggest communists. The menace of communism could be discursively connected with methamphetamine illegal production and smuggling when mediated by Korean people. In other words, Korean peopleprobably because of the large number of marginalized Koreans in Japanwas a discursive resource which was an available and perhaps even necessary linkage between the contemporary perceptions of the menace of communism and the illegal production and smuggling of methamphetamine. In October 1953 the Metropolitan Police conducted inspections of Korean villages and other areas for suspected violation of the Stimulant Control Law, which resulted in the arrest of many Koreans for the illegal production of methamphetamine (National Diet, 1953, October 30).21 In total, there were 38,514 arrests, the second largest number of arrests in the history of the legislation, leading to an upward curve in the number of arrests in the 1950s (see Figure 2). The chief of the Metropolitan Police noted that 71% of the people arrested were Korean and that the police had conducted an intensive search of the places where there supposedly existed many sites for illegal production and smuggling, especially in the east of Tokyo.22 In other words, the figure of 71% pertained to the inspection of specific places, mainly Korean villages.23 These trends accelerated in 1954, especially after the Kyokochan incident. Illustrative in this regard was the debate in the Diet concerning amendments to the Stimulant Control Law, which started in May 1954, just after the murder of Kyoko

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

736

METHAMPHETAMINE USE IN JAPAN AFTER WWII

Hosoda. In that debate, the Stimulant Control Law was discussed in terms of revisions to the Immigration Law, including the enforced repatriation of Koreans (National Diet, 1954, May 25). This was because of public perceptions that Koreans smuggled stimulants and many of them were communists or communist sympathizers who were engaged in attacks on Japan and the Japanese people. However, the clause providing for enforced repatriation was not included in the final bill because of ongoing disagreement with the government of South Korea. Illegal production and smuggling of methamphetamine had already been discussed with the communist regimes of North Korea and China, explicitly and, almost always, because of Japanese fears of communist invasion after the Korean War was suspended on July 27, 1953. When the campaign against methamphetamine was launched in October 1954, the chief of the crime-prevention division of the Metropolitan Police commented in a newspaper that the police would tighten controls over the smugglers, even when Korean powers tried to interrupt their investigations (Asahi Shinbun, 1954, 15 Oct.). Similarly, the report of the Metropolitan Police on its campaign began on this nationalist note: In order to maintain the purity of Japanese ethnicity and, especially, to attempt to raise sound young people who will contribute to our future generations, now is the time when we have to pluck up our courage to eradicate stimulants (Metropolitan Police, 1955, p. 1). Later, the report made explicit reference to Koreans:

Seventy percent of these smugglers, unlawful producers, and bootleggers consist of Korean people and they gnaw at the bodies and spirits of approximately 1,500,000 of our fellow countrymen. At its most extreme, we seem to be living with a large crowd of people going insane and becoming brutal offenders. . . . Our fellow countrymen, especially young people, are the victims of Korean people seeking their own interests, and the result will be the destruction of our future generations, who will become sick and decline in health and finally turn into addicts who will destroy our entire social order. . . . Korean people who are well informed of the dangers of

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

737

stimulants rarely use it themselves nor do they allow their children to use it. (Ibid.. pp. 19-20)

The above could be considered nationalist rhetoric, because it distinguishes between we and they with negative attributes linked to stories inspired by them (Billig, 1995). As I have already suggested, this type of nationalist talk had been strong and popular since 1953. Further, its suggestion that methamphetamine users, especially young people, were victims of the smugglers had been popular since the late 1940s and early 1950s, when methamphetamine began to be treated as a problem. Such nationalist talk can be said to have emerged from arguments that young people were victims whereas the Koreans were assailants. I do not argue that claims regarding communism and Korean illegal production and smuggling were patently false, but rather that discussions over methamphetamine use were often fueled by perceived threats, real or implied, to the Japanese people. This type of discourse was so strong that it effectively functioned as an intellectual frame in which methamphetamine use could be critiqued, because such criticism of methamphetamine use implied not individual vice but a threat to the future of Japan.24 Closing remarks I have argued in this article that the abrupt change in the discourse of methamphetamine in 1950s in Japan was caused by the transformation of the narratives of methamphetamine use on the part of users themselves and by nationalist dialogue concerning illegal production and smuggling of methamphetamine. In support of this claim, I have outlined the events that led to the passage of the Stimulant Control Law and also analyzed the narratives on methamphetamine that emerged in subsequent years.

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

738

METHAMPHETAMINE USE IN JAPAN AFTER WWII

This argument has some theoretical implications. The process of extending legal control over methamphetamine production, as well as changes in the narratives and images of methamphetamine, can be seen as the result of a moral panic that arose in post-war situation Japan, a panic in which moral barricades (Cohen, 1972) were set up to prevent post-war disorder. Moral Panic theory is very useful in explaining transformations in methamphetamine narratives. However, there are important points that need to be made about Moral Panic theory. One of its main assumptions is that there should be some latent moral panic phenomena that precede the emergence of perceptions of a social problem. That is why most interpretations based on Moral Panic theory focus on the content of the panic and the timing of the emergence of the problem, which are often revealed by materials and descriptions in mass media (e.g., Ben-Yehuda, 1990). However, the link between the preceding panic and the following problem is not necessarily clear because the link itself is constituted by the description of the account by the researcher. In other words, the link between the panic and the problem is often described as the link between categories developed by the researcher to make sense of the causal relationship. The link between categories could be said to be a self-fulfilling prophecy. This caution does not mean that any interpretation based on Moral Panic theory is invalid. Rather, it is possible for us to develop points of view, such that streams of language games (to quote Wittgenstein) related to differing topics meet each other, and subsequently new or revised versions of reality emerge through the articulation of discourses. From this kind of viewpoint, methamphetamine and nationalism were discursively joined in Japan in the post-war period, and dialogue between them yielded a movement against external forces that were presumed to be hostile. The merit of this type of interpretation is that we can describe relationships between the discourses without assuming any causal relationship.

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

739

As stated at the outset of this article, it was widely believed immediately after the Second World War that Japan had a methamphetamine problem because of the then prevailing social disorder, which produced large numbers of cases of methamphetamine psychosis. However, through careful analyses of the historical record, an alternative interpretation becomes possible. Methamphetamine discourse and nationalism joined in the 1950s, articulated each other, and brought into being the dominant narratives of today. Notes

1. Nagai first mentioned methamphetamine (Phenyl-methylaminopropan) in an article published in 1893 (Nagai, 1893). However, according to Miura, Nagai discovered it while researching Maou (Ma Huang in Chinese) in 1888 (Miura, 1941). Miura experimented with Nagais extracts of Maou (Ibid. Yamashita, 1966). Methamphetamine (Phenyl-methylaminopropan) and amphetamine (Phenyl-aminopropan) both belong to a family of ephedrine-based stimulant drugs. However, their structural formulas are slightly different from each other. Methamphetamine has CH3 (a methyl group) instead of H at one end of the formula of amphetamine. This difference is thought to make methamphetamine more effective than amphetamine. Since the 1970s, stimulants, including methamphetamine, have been called Shabu in common parlance in Japan. In recent years, it has sometimes been called Speed or S (for Speed). Much of the stock of methamphetamine in the Armed Forces was confiscated by General Headquarters (GHQ) after the war. The GHQ subsequently returned it to the Ministry of the Health and Welfare (National Diet, 1949, November 30). The author conducted interviews with elderly people, including veterans, in March 1997 and January 2006. Interviews with younger people using stimulants and other drugs in Japan are also available in Sato (2000). The Ministry of Health and Welfare produced many administrative guidelines and regulations on stimulants (methamphetamine and amphetamine) after 1948. One of its most popular measures defined stimulants as strong medicine. Strong medicine means that identification and usage outline was needed at time of purchase; also, persons under fourteen years of age could not purchase it. On August 15, 1948 ministry regulation no. 37 under the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law defined any such medicine of over 1mg per tablet as strong

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

740

METHAMPHETAMINE USE IN JAPAN AFTER WWII

medicine. And on March 28, 1949 the ministry amended the regulation to define all tablets and powder containing methamphetamine and amphetamine as strong medicine. Before this amendment was put in place, the ministry had announced to pharmaceutical companies that it had a plan to control the sale of all stimulants, and that these medicines needed to alert consumers that they might cause habituation (Ikuta, 1951; National Diet, 1950, December 5). 7. Interestingly, people who were deemed to fall in this category could talk about their experiences of methamphetamine in the same terms. For example, the novelist Ango Sakaguchi (19061955) wrote: When the drug does not work so effectively, you could just get another one. It is important that you should start with a small amount. You must not accept the mundane belief that stimulants do not have any effect unless you increase the dosage; I did not experience any harm from those. It is sleeping tablets that harm your health (Sakaguchi, 1950, p. 7). Following his death, Sakaguchi has become famous for his use of stimulants, in part because of an essay written in 1958 by Shiro Ozaki, another novelist and one of Sakaguchis friends (Ozaki, 1958). At a time when claims were being made concerning the psychotic-inducing effects of stimulants, Ozaki stated that after 1949 Sakaguchi himself was psychotic. This type of discourse is called attribution talk in discourse analysis (Edwards & Potter, 1992). This was one among several possible interpretations. He had long suffered from tuberculosis and several times had experienced hemoptysis (spitting of blood), for which he had received medical treatment. His methamphetamine use might thus be interpreted as reflective of his character, a point that was made in some essays about him (Fujisawa, 1978). Inoues concern presumably was based on an article in Asahi Shinbun a week earlier, entitled Young Philopon Patients: Theft and Extortion to Earn Money for Philopon: Metropolitan Police Begins to Control (Shounen Philopon Kanja: Kusuridai Hosisa kara Nusumi ya Yusuri: Keishityo Torishimari ni Nori Dasu) (Asahi Shinbun, 1949, 19 Oct.). For example, an article entitled Juvenile Philoponia (Shounen Philoponia) in the magazine Shukan Asahi on December 12, 1949 stated that street children bought vitamin and dextrose ampoules because they needed something to keep their energy high when they could not get Philopon. For many children, especially those without parents in urban areas, food was difficult to obtain. Research study done in March 1947 showed that the number of runaway children had increased three times since 1945 and that most of them ran away from urban areas to countryside to get food (Akatsuka, 1982, pp. 17-18).

8. 9.

10.

11.

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

741

12.

On October 11, 1950 the newspaper Saitama Shinbun reported the incident under the headline Mass Sexual Assault by a Delinquent Group in Tsuchiai Village, Six People Including Women Arrested (Huryou Ren ga Shuudan Boukou, Tsuchiai Mura, Onna mo Mazaru Rokumei Kenkyo) (Saitama Shinbun, 1950, October 11). Two weeks later, Saitama Shinbun described the police investigations in the village and stated that over one hundred were raped (Okasareta mono Hyakunin Ijou) (Saitama Shinbun, 1950, October 23). The same report attributed the incident to the presence of only one policeman in the village and the indifference of parents to their childrens behavior. However, the police had a different view, claiming that Tsuchiai had long been famous for its brutality and that the cause of the incident was the stimulants that were used by almost all those arrested; further, they blamed the manufacturer of the stimulants, Toyama Chemical (National Council of Youth Problems, 1950: 98). In addition, in a debate in the Diet in November 1950, another culprit was identified: indecent magazines, known as Kasutori Zasshi, which were widely circulated in post-war Japan (National Diet, 1950, November 29). Kondo (1955) argued that the Mass Sexual Assault Incident was relatively more important than the actions of Toyama Chemical in the passage of the Stimulant Control Law because it showed that Neoagotin addiction and psychosis was at the root of such behavior. However, Kondo discussed it retrospectively in 1955. This suggests that the psychotic effects of methamphetamine were not an issue in 1950; certainly, they were not mentioned in Diet debates. These were elaborated upon mainly after 1954. Interestingly, in the ensuing debate in the Diet over stimulant-control legislation, one representative (who later became one of the authors of the final bill) stated that the bill should focus only on limiting use, on the ground that the New Police Force itself (which later became the Self-Defence Armed Forces of Japan) intended to use stimulants. This opinion was criticized by the psychopathologists who testified before the Diet (National Diet, 1951, February 15). Nevertheless, it suggests that the use of stimulants did not necessarily elicit strong reactions in all circles and that some could still talk about their positive effects. Ueno is a town in the Taito district, to the east of Tokyo, where many smugglers were alleged to have sold methamphetamine. This was Shou Hayashi, M.D., the director of Matsuzawa Hospital of Tokyo (Asahi Shinbun, 1951, May 7). However, addicts were not always treated as criminals, as they are today. The chief of the Metropolitan Police, responding to the Diet representative who argued that addicts should be arrested and treated as criminals, said that addicts should be treated as patients unless they committed crimes (National Diet, 1954, May 20).

13.

14.

15. 16. 17.

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

742

METHAMPHETAMINE USE IN JAPAN AFTER WWII

18.

See Sacks, 1970 (1992), pp. 215-221, and Edwards, 1997, pp. 71-72. Sackss discussion of doing being ordinary sees ordinariness as a concerted interactional accomplishment. For example, an opinion survey conducted in October 1983 showed that 94% of the respondents who said that that they knew the word stimulant answered yes when asked whether they realized the habit-forming nature of methamphetamine. And 94% of the subjects stated that one became paranoid after using the stimulant for some time (Cabinet Office, 1984). In a similar opinion survey in January 2006, 98.3% of the respondants said that methamphetamine was a drug terrifying in its effects; 89.4% said that it was terrifying because it led to intoxication; and 70.9% said that a person became addicted to it after using it only once (Cabinet Office, 2006). It was believed for a long time, even by recovered alcoholics and by those who supported recovery from alcoholism, that stimulant addiction could not be similarly overcome (Kondo, 1997, 2000). The inspection continued in the next month, November 1953, when, following the passage of the law for establishing the Council of Youth Problems that June, the campaign for protecting young people (Seishounen Hogo Ikusei Undou) was launched. The Chief of the Metropolitan Police and the director of the criminal-investigation division of the National Police related how they had scrutinized possible connections between the Japanese Communist Party, other communist activists, and Korean manufacturers and smugglers of illegal substances; however, firm evidence of such connections was still lacking (National Diet, 1954, 20 May). As time passed, the identity of the hostile forces discussed in methamphetamine narratives gradually changed, the new targets being Japanese gangs (1970s and 1980s), Iranian migrants to Japan seeking employment (1990s), and, currently, North Korean agents. Recall the article The Actual Conditions of Terrible Illness (Philopon) that Disrupts Our Country, cited above, in which an ex-user of methamphetamine narrated his past problems. As this example shows, nationalist discourse functions as the frame of the narrative of the user of methamphetamine.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

743

References Akatsuka, Y., ed. (1982). Seishounen Hikou Hanzai shi Shiryou (Materials for the

History of Juvenile Delinquency and Crime), Vol. 1. Tokyo: Kankando. Anonymous. (1954). Osorubeki Boukoku Byou (Philopon) no Jittai: Seishounen wo nerau nikutai no akuma (The Actual Conditions of the Terrible Illness [Philopon] That Disrupts Our Country: The Devil Taking Aim at Young Peoples Modies), King, October. 104-112. Ariyama, N. (1941). Shin Kouhun Zai B-Phenylisopropylamin (New Stimulant B-Phenylisopropylamin), Psychiatria et Neurologia Japonica, 45, 730-742. Asahi Shinbun. Ben-Yehuda, N. (1990). The Politics and Morality of Deviance. New York, NY: State University of New York Press. Billig, M. (1995). Banal Nationalism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Buttny, R. (1993). Social Accountability in Communication. Thousand Oaks, CA.: Sage. Cabinet Office. (1984). Hanzai oyobi Kakuseizai ni kansutu Yoron Chousa (Opinion Survey on Crime and Stimulant [October 1983]). Cabinet Office. (2006). Yakubutsu Ranyou Taisaku ni kansuru Yoron Chousa (Opinion Survey on Measures to Prevent Drug Abuse [January 2006]). Cohen, S. (1972). Folk Devils amd Moral Panics: The creation of the mods and rockers. London: MacGibbon and Kee. Edwards, D. (1997). Discourse and Cognition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Edwards, D. & J. Potter. (1992). Discursive Psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Fujisawa, T. (1978). Oda Sakunosuke no Omoide (Memories of Oda Sakunosuke), Geppou, 50, in the series Gendai Bungaku Taikei. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobou. Garfinkel, Harold. 1967. Studies in Ethnomethodology. Cambridge, U.K.: Polity Press. Hirano, I. (1949, December). Philopon Ka: Sengo Sakka no Seitai Philopon (Disaster: Modes of lives of post-war novelists), Sekai Hyouron (World View).pp. 68-71. Horimi, T., Hashimoto, S., Inoue, K., Soya, K. & Egawa, S. (1940). Seishin Joutai ni oyobosu Hospitan Sayou ni tsuite (On the effect of Hospitan on the state of mind), Mitteilungen der Medizinischen Gesellschaft zu Osaka, 39, 827-837.

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

744

METHAMPHETAMINE USE IN JAPAN AFTER WWII

Ikuta, B. (1951). Kakuseizai ni tsuite (On Stimulants), Kagaku to Sousa (Science and Crime Detection), 4(2), 28-53. Iwata, S. (1947). Philopon Renyou ni tsuite no Kaishin (Cautions on Regular Use of Philopon), Nihon Naikagakkai Zasshi (Journal of the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine), 36(5/6/7), 98-99. Japan Medical Association. (1950). Ronsetsu: Philopon wa Dounaru ditorial (Editorial: Where does Philopon go), Nihon Ishikai Zasshi Journal of Japan Medical Association, 24(2), 141. Kanao, S. (1960). Nagai Nagayoshi Den (Biography of Nagayoshi Nagai). Tokyo: Nihon Yakugaku (Pharmaceutical Society of Japan). Kondo, K. (1955). Kakuseizai Jihan no Kaiko to Tembo (Retrospective and Prospective Considerations on the Offenders of Stimilant Control Law), Keisatsu Gaku Ronshu, Journal of Police Science, 8(1): 40-51. Kondo, T. (1997). Yakubutsu Izon (Drug Addiction). Tokyo: Taikaisha. Kondo, T. (2000). Yakubutsu Izon wo Koete (Beyond Drug Addiction). Tokyo: Kaitakusha. Metropolitan Police Headquarters. (1955). Kakuseizai (Philopon) no Gaiaku to sono Taisaku (The Harm of Stimulants [Phipolon] and the Measures to Cope with it). Miura, K. (1941). Maou yori Seishutsu seru Joken Kakuseizai ni tsuite (On the stimulants derived from Ephedrae Herba), Jikken Ihou, Experimental Medical Review, 28, 7-12. Muroo, T. (1982a). Kakuseizai Jigoku kara no Kokuhaku (Confessions from the hell of stimulants), Gendai (Mondern Tmes), pp. 398-410. Muroo, T. (1982b). Kakuseizai: Shiroi Kona no Kyouhu (Stimulant: Terrors of white powder). Tokyo: San-ichi Shobou. Nagai, Nagayoshi. (1893). Kanyaku Maou Seibun Kenkyu Seiseki (Results of the Research of the Contents of Chinese Medicine Maou), Yakugaku Zasshi, Journal of the Pharmaceutical Society of Japan, 139, 901-33. National Council of Youth Problems. (1950). December 9 & 10, Minutes of National Council of Youth Problems. National Diet. (1949). October 24, Minutes of the Committee on Welfare of the 5th House of Councilors, no. 7. National Diet. (1949). November 24, Proceedings of the Plenary Session of the 5th House of Councilors, no. 18. National Diet. (1949). November 30, Minutes of the Committee on Budget of the 6th House of Councilors, no. 10.

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

745

National Diet. (1950). November 17, Minutes of the Committee on Local Administration of the 8th House of Councilors, no. 12 (closing). National Diet. (1950). November 29, Proceedings of the Plenary Session of the 9th House of Councilors, no. 5. National Diet. (1950). December 5, Minutes of the Committee on Welfare of the 9th House of Councilors, no. 3. National Diet. (1951). February 15, Minutes of the Committee on Welfare of the 10th House of Councilors, no. 6. National Diet. (1951). February 22, Minutes of the Committee on Welfare of the 10th House of Councilors, no. 8. National Diet. (1951). May 23, Minutes of the Committee on Welfare of the 10th House of councilors, no. 29. National Diet. (1951). May 25, Minutes of the Committee on Welfare of the 10th House of councilors, no. 31. National Diet. (1952). May 6, Proceedings of the Plenary Session of the 13th House of Representatives, no. 35. National Diet. (1952).May 7 , Minutes of the Committee on Local Administration of the 13th House of Representatives, no. 38. National Diet. (1952). May 9, Minutes of the Committee on Judicial Affairs of the 13th House of Representatives, no. 47. National Diet. (1952). July 1, Proceedings of the Plenary Session of the 13th House of Councilors, no. 59. National Diet. (1953). July 17, Minutes of the Committee on Judicial Affairs of the 16th House of Councilors, no. 15. National Diet. (1953). October 30, Minutes of the Committee on Welfare of the 17th House of Councilors, no. 1. National Diet. (1954). April 20, Minutes of the Committee on Education of the 19th House of Representatives, no. 26. National Diet. (1954).May 14 , Proceedings of the Plenary Session of the 19th House of Councilors, no. 14. National Diet. (1954). May 20, Minutes of the Committee on Welfare of the 19th House of Representatives, no. 48. National Diet. (1954). May 25, Minutes of the Committee on Welfare of the 19th House of Councilors, no. 45. Ozaki, S. (1958). Suimin Yaku to Kakuseizai (Sleeping Tablet and Stimulant), in Ozaki Shiro Zenshu dai 5 kan (The Complete Works of Ozaki Shiro Vol. 5). Tokyo: Kodansha, 294-326.

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

746

METHAMPHETAMINE USE IN JAPAN AFTER WWII

Prime Ministers Office. (1977). Headquarters for the Promotion of Measures to Prevent Drug Abuse. Shiroi Kona no Kyoufu (Terrors of the White Powder). Sacks, H. (1970). Lecture 1: Doing being ordinary. In H. Sacks, Lectures on Conversation, Vol. 2. London: Blackwell, 1992. 215-221. Saitama Shinbun. (1950,1 October 1, October 20, October 23. Sakaguchi, A. (1950) Mayaku, Jisatsu, Shukyo (Narcotics, Suicide, Religion), Bungei Shunjuu. Sato, A. (2000). Life with Drugs: Research on controlled use of drugs, Bungakubu Ronsou, 68, 39-65 Sato, A. (2006). Kakuseizai no Shakai shi: Drug, Discourse, Touchi Gijutsu (Drug and Discourse: Methamphetamine in Japan). Tokyo: Toshindo. Scott, M. B., & Lyman, S, M. (1968). Accounts, American Sociological Review, 33, 46-62. Shukan Sankei. (1977, May 2). Keisatsu Chou hen Kakuseizai Shudoku Sha no Koe ni Koubai Kibou ga Sattou shita Haikei (The Reason Why The Voices of Stimulant Addicts, by the National Police, had a Rush of Orders), pp. 188-190. Suwaki, H., Fukui, S., & Komura, K. (1997).Methamphetamine Abuse in Japan: Its 45 year history and the current situation, in H. Klee, ed., Amphetamine Misuse: International perspectives on current trends. New York: Harwood Academic Press. pp. 199-214. Suzuki, S, (1949). Geinin to Philopon (Performers and Philopon), Nihon Ishi-kai Zasshi, Journal of Japan Medical Association, 23(7), 474. Takeyama, T. (1949, December). Philopon Dangi (Philopon and Righteousness), Kaizo (Reconstruction), pp. 88-90. Tamura, M. (1982). Kakuseizai no Ryukou to Hou Kisei (Methamphetamine Epidemic and Law Enforcement), Hanzai Shakaigaku Kenkyu, Japanese Journal of Sociological Criminology, 7, 4-32. Tatetsu, S., Goto, A., & Fujiwara, T. (1956). Kakuseizai Chudoku (The Methamphetamine-Psychosis). Tokyo: Igaku Shoin. Yamashita, A. (1966). Nagai Nagayoshi ni tsuite no Ichi Kousatsu (A Consideration of Nagayoshi Nagai: His research on ephetrine), Kagakushi Kenkyu (Journal of History of Science), 76, 156-163. Yamashita, A. (1969). Nagai Nagayoshi ni tsuite no Ichi Kousatsu (Additional Notes to A Consideration of Nagayoshi Nagai), Journal of History of Science, Japan, 79, 149-150.

CDP Winter 2008 article by: Sato 09-09-2009 Rev.

You might also like

- Spatial Audio Processing: MPEG Surround and Other ApplicationsFrom EverandSpatial Audio Processing: MPEG Surround and Other ApplicationsNo ratings yet

- Paradox and Representation: Silenced Voices in the Narratives of Nakagami KenjiFrom EverandParadox and Representation: Silenced Voices in the Narratives of Nakagami KenjiNo ratings yet

- The Poison System in jAPANDocument14 pagesThe Poison System in jAPANMuhamad Erfan MaulidaNo ratings yet

- Widespread Zombification in the 21st Century and the Wars of the Zombie Masters: DRUGS: For Kids - and the Occasional Interested ParentFrom EverandWidespread Zombification in the 21st Century and the Wars of the Zombie Masters: DRUGS: For Kids - and the Occasional Interested ParentNo ratings yet

- Hand in Glove-The Burma Army and The Drug Trade in Shan StateDocument64 pagesHand in Glove-The Burma Army and The Drug Trade in Shan StatePugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Sex Tourism in ThailandDocument14 pagesSex Tourism in ThailandNil Ng100% (1)

- Solving Large Sparse Nonlinear SystemsDocument7 pagesSolving Large Sparse Nonlinear SystemslesutsNo ratings yet

- Quantum Computing An Emerging EcosystemDocument40 pagesQuantum Computing An Emerging EcosystemAmaratpal KaurNo ratings yet

- History of Mass Spectrometry of Organic MoleculesDocument67 pagesHistory of Mass Spectrometry of Organic MoleculesEmir Gerardo Monterrey GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- (+) NIST-monograph175 Funciones y Tablas de Referencia de Fem de Temperatura para Termopares Basados en ITS-90 PDFDocument640 pages(+) NIST-monograph175 Funciones y Tablas de Referencia de Fem de Temperatura para Termopares Basados en ITS-90 PDFLucio ArmasNo ratings yet

- Mems SyllabusDocument2 pagesMems SyllabusSony RamaNo ratings yet

- Lab ManualDocument39 pagesLab ManualAzlinda AdzarNo ratings yet

- Japan's Philopon ProblemDocument6 pagesJapan's Philopon ProblemAnnisa LarasatiNo ratings yet

- Japan and MethamphetamineDocument43 pagesJapan and MethamphetamineCaitlinRose100% (1)

- Neurologic Manifestations of Chronic Methamphetamine Abuse: Daniel E. RusyniakDocument15 pagesNeurologic Manifestations of Chronic Methamphetamine Abuse: Daniel E. RusyniakAlmas TNo ratings yet

- Amphetamine FaqDocument30 pagesAmphetamine FaqTowhidulIslamNo ratings yet

- History of StimulantsDocument4 pagesHistory of StimulantsMuhammad Taha SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- OrganicDocument35 pagesOrganicKristina CoeNo ratings yet

- History of MethamphetamineDocument3 pagesHistory of Methamphetaminegloria4966No ratings yet

- Drug Education and Vice ControlDocument12 pagesDrug Education and Vice ControlJhuan Paulo Aquino ClavecillasNo ratings yet

- Speed-Speed-Speedfreak: A Fast History of AmphetamineFrom EverandSpeed-Speed-Speedfreak: A Fast History of AmphetamineRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Journalism: in The Japan Times Post-War Japan in Photographs: Erasing The Past and Building The FutureDocument21 pagesJournalism: in The Japan Times Post-War Japan in Photographs: Erasing The Past and Building The FutureTolgaÖzbeyNo ratings yet

- MethamphetamineDocument6 pagesMethamphetamineallison12575% (4)

- Drug Use and Abuse Is As Old As Mankind ItselfDocument2 pagesDrug Use and Abuse Is As Old As Mankind ItselfCherryl Niqitha LahebaNo ratings yet

- Medical Ethics (3rd Edition) : Journal of The Royal Society of Medicine May 2002Document9 pagesMedical Ethics (3rd Edition) : Journal of The Royal Society of Medicine May 2002Muhammad AkibNo ratings yet

- OpiumDocument8 pagesOpiumcarlitog782No ratings yet

- Tattered Kimonos in Japan: Remaking Lives from Memories of World War IIFrom EverandTattered Kimonos in Japan: Remaking Lives from Memories of World War IINo ratings yet

- Chemistry of Opium CompleteDocument9 pagesChemistry of Opium Completecarlitog782No ratings yet

- The Red, White & Blue MethodDocument14 pagesThe Red, White & Blue MethodNeurule Somme-Yong Abdul Jalal75% (4)

- Methamphetamine: Its History, Pharmacology and TreatmentFrom EverandMethamphetamine: Its History, Pharmacology and TreatmentRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Contesting Precarity in Japan: The Rise of Nonregular Workers and the New Policy DissensusFrom EverandContesting Precarity in Japan: The Rise of Nonregular Workers and the New Policy DissensusNo ratings yet

- Mephedrone PDFDocument20 pagesMephedrone PDFStephan LewisNo ratings yet

- PD Drugs-EducationDocument21 pagesPD Drugs-EducationJohn PabloNo ratings yet

- Book Review On Made in Japan by Abhash PaneruDocument5 pagesBook Review On Made in Japan by Abhash Paneruabhash paneruNo ratings yet

- The Way of the Heavenly Sword: The Japanese Army in the 1920'sFrom EverandThe Way of the Heavenly Sword: The Japanese Army in the 1920'sRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Advances in BiophysicsDocument3 pagesAdvances in BiophysicsAnita RosdianaNo ratings yet

- Conveying Misinformation: Top-Ranked Japanese Books On TobaccoDocument6 pagesConveying Misinformation: Top-Ranked Japanese Books On TobaccoDenish MikaNo ratings yet

- Asia-Pacific Psychiatry - 2022 - Nakamura - A Century of Morita Therapy What Has and Has Not ChangedDocument8 pagesAsia-Pacific Psychiatry - 2022 - Nakamura - A Century of Morita Therapy What Has and Has Not Changeduri wernukNo ratings yet

- A Century of Morita Therapy What Has and Has Not ChangedDocument8 pagesA Century of Morita Therapy What Has and Has Not Changedm01.abousalehNo ratings yet

- UNIT731Document13 pagesUNIT731chan2030No ratings yet

- HayDocument22 pagesHayCường Sirôô100% (1)

- Social and Legal Factors Related To Drug Abuse in The United States and JapanDocument7 pagesSocial and Legal Factors Related To Drug Abuse in The United States and JapanVic BecerrilNo ratings yet

- Crystal Methamphetamine in The Philippines - Bosworth - 08 - 04Document16 pagesCrystal Methamphetamine in The Philippines - Bosworth - 08 - 04Andrew C BosworthNo ratings yet

- Made in Japan Akio Morita and SonyDocument3 pagesMade in Japan Akio Morita and SonyRohit Nerurkar100% (1)

- The Politics of Labor Legislation in Japan: National-International InteractionFrom EverandThe Politics of Labor Legislation in Japan: National-International InteractionNo ratings yet

- Japan's New Product Liability ADR Centers: Bureaucratic, Industry, or Consumer Informalism?Document42 pagesJapan's New Product Liability ADR Centers: Bureaucratic, Industry, or Consumer Informalism?Emeka NkemNo ratings yet

- Trigger Points and Muscle Chains 2nd EditionDocument259 pagesTrigger Points and Muscle Chains 2nd EditionDan100% (1)

- Chemical Warfare Agents Toxicology and TreatmentDocument2 pagesChemical Warfare Agents Toxicology and TreatmentMegitsu NavaNo ratings yet

- McLelland ShortHistoryHentai2005 PDFDocument13 pagesMcLelland ShortHistoryHentai2005 PDFmadadudeNo ratings yet

- Cultural Sociology of Mental Illness n28Document5 pagesCultural Sociology of Mental Illness n28Andi BintangNo ratings yet

- Manga Movies Project Report 1 PDFDocument45 pagesManga Movies Project Report 1 PDFtesth2No ratings yet

- Japanese Workers in Protest: An Ethnography of Consciousness and ExperienceFrom EverandJapanese Workers in Protest: An Ethnography of Consciousness and ExperienceNo ratings yet

- Japan68 PDFDocument32 pagesJapan68 PDFDon MetalNo ratings yet

- Vice and Drug Education and ControlDocument122 pagesVice and Drug Education and ControlJulie Ann EbaleNo ratings yet

- Kesari Tours and Travel: A Service Project Report OnDocument15 pagesKesari Tours and Travel: A Service Project Report OnShivam Jadhav100% (3)

- 99 Names of AllahDocument14 pages99 Names of Allahapi-3857534100% (9)

- Jurnal SejarahDocument19 pagesJurnal SejarahGrey DustNo ratings yet

- Form Audit QAV 1&2 Supplier 2020 PDFDocument1 pageForm Audit QAV 1&2 Supplier 2020 PDFovanNo ratings yet

- Philippine National Development Goals Vis-A-Vis The Theories and Concepts of Public Administration and Their Applications.Document2 pagesPhilippine National Development Goals Vis-A-Vis The Theories and Concepts of Public Administration and Their Applications.Christian LeijNo ratings yet

- CH 1 QuizDocument19 pagesCH 1 QuizLisa Marie SmeltzerNo ratings yet

- A Brief Ion of OrrisaDocument27 pagesA Brief Ion of Orrisanitin685No ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - AuditDocument26 pagesChapter 2 - AuditMisshtaCNo ratings yet

- Dda 2020Document32 pagesDda 2020GetGuidanceNo ratings yet

- A Study On Cross Cultural PracticesDocument56 pagesA Study On Cross Cultural PracticesBravehearttNo ratings yet

- In-CIV-201 INSPECTION NOTIFICATION Pre-Pouring Concrete WEG Pump Area PedestalsDocument5 pagesIn-CIV-201 INSPECTION NOTIFICATION Pre-Pouring Concrete WEG Pump Area PedestalsPedro PaulinoNo ratings yet

- Fatawa Aleemia Part 1Document222 pagesFatawa Aleemia Part 1Tariq Mehmood TariqNo ratings yet

- AJWS Response To July 17 NoticeDocument3 pagesAJWS Response To July 17 NoticeInterActionNo ratings yet

- Upcoming Book of Hotel LeelaDocument295 pagesUpcoming Book of Hotel LeelaAshok Kr MurmuNo ratings yet

- Calendario General 2Document1 pageCalendario General 2Santiago MuñozNo ratings yet

- Department of Mba Ba5031 - International Trade Finance Part ADocument5 pagesDepartment of Mba Ba5031 - International Trade Finance Part AHarihara PuthiranNo ratings yet

- HumanitiesprojDocument7 pagesHumanitiesprojapi-216896471No ratings yet

- Starmada House RulesDocument2 pagesStarmada House Ruleshvwilson62No ratings yet

- 5 15 19 Figaro V Our Revolution ComplaintDocument12 pages5 15 19 Figaro V Our Revolution ComplaintBeth BaumannNo ratings yet

- Ekotoksikologi Kelautan PDFDocument18 pagesEkotoksikologi Kelautan PDFMardia AlwanNo ratings yet

- 01-Cost Engineering BasicsDocument41 pages01-Cost Engineering BasicsAmparo Grados100% (3)

- Testamentary Succession CasesDocument69 pagesTestamentary Succession CasesGjenerrick Carlo MateoNo ratings yet

- 10th Grade SAT Vocabulary ListDocument20 pages10th Grade SAT Vocabulary ListMelissa HuiNo ratings yet

- Nef Elem Quicktest 04Document2 pagesNef Elem Quicktest 04manri3keteNo ratings yet

- The Mystical Number 13Document4 pagesThe Mystical Number 13Camilo MachadoNo ratings yet

- Vayigash BookletDocument35 pagesVayigash BookletSalvador Orihuela ReyesNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To The Catholic Charismatic RenewalDocument5 pagesAn Introduction To The Catholic Charismatic RenewalNoah0% (1)

- Insura CoDocument151 pagesInsura CoSiyuan SunNo ratings yet

- Open Quruan 2023 ListDocument6 pagesOpen Quruan 2023 ListMohamed LaamirNo ratings yet