Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Primary Immune Deficiency

Uploaded by

Divya SoundarajanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Primary Immune Deficiency

Uploaded by

Divya SoundarajanCopyright:

Available Formats

Primary Immunedeficiency Disease: Introduction

When part of the immune system is either absent or not functioning properly, it can result in an immune deficiency disease. When the cause of this deficiency is hereditary or genetic, it is called a primary immunodeficiency disease (PIDD). Researchers have identified more than 150* different kinds of PIDD.

The immune system is composed of white blood cells. These cells are made in the bone marrow and travel through the bloodstream and lymph nodes. They protect and defend against attacks by "foreign" invaders such as germs, bacteria and fungi.

In the most common PIDDs, different forms of these cells are missing. This creates a pattern of repeated infections, severe infections and/or infections that are unusually hard to cure. These infections may attack the skin, respiratory system, the ears, the brain or spinal cord, or in the urinary or gastrointestinal tracts.

In some instances, PIDD targets specific and/or multiple organs, glands, cells and tissues. For example, heart defects are present in some PIDDs. Other PIDDs alter facial features, some stunt normal growth and still others are connected to autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Chronic Granulomatous Disease (CGD)

Common Variable Immunodeficiency (CVID)

DiGeorge Syndrome (DGS)

Selective IgA Deficiency

Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID)

X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia (XLA)

Chronic Granulomatous Disease (CGD)

CGD Overview

Chronic Granulomatous Disease (CGD) is an inherited primary immunodeficiency disease (PIDD) which increases the bodys susceptibility to infections caused by certain bacteria and fungi. Granulomas are masses of immune cells that form at sites of infection or inflammation.

People with CGD are unable to fight off common germs and get very sick from infections that would be mild in healthy people. This is because the presence of CGD makes it difficult for cells called neutrophils to produce hydrogen peroxide. The immune system requires hydrogen peroxide to fight specific kinds of bacteria and fungi.

These severe infections can include skin or bone infections and abscesses in internal organs (such as the lungs, liver or brain).

Aside from the defective neutrophil function in CGD, the rest of the immune system is normal. People with CGD can be generally healthy until they become infected with one of these germs. The severity of this infection can lead to prolonged hospitalizations for treatment.

Children with CGD are often healthy at birth, but develop severe infections in infancy or early childhood. The most common form of CGD is genetically inherited in an X-linked manner, meaning it only affects boys. There are also autosomal recessive forms of CGD that affect both sexes.

CGD Symptoms & Diagnosis

Symptoms People with CGD can easily fight off some infections, but not those that need the bodys natural ability to produce hydrogen peroxide to control disease. For this reason, symptoms of recurrent bacterial or fungal infections may be sporadic.

CGD may involve any organ system or tissue of the body, but infections are usually found in the: Skin Lungs Lymph nodes Liver Bones Occasionally the brain

Wounds may also have trouble healing and an inflammatory condition known as granuloma may develop.

Pneumonia caused by a fungus such as Aspergillus is a red flag for CGD and often results in testing.

Diagnosis The timing of diagnosing CGD is often dependent upon when an infant or child begins having recurrent bacterial or fungal infections associated with the disease.

The most accurate test to confirm CGD is made by measuring the amount of hydrogen peroxide produced by the bodys cells.

CGD Treatment & Management

The best treatment plan for CGD is to prevent infections from occurring. Special preventative antibiotics are a mainstay of treatment for CGD. These greatly reduce the chances of infection.

Bone marrow transplant is another treatment option for some people with severe symptoms of CGD.

Common Variable Immunodeficiency (CVID)

CVID Overview

Common Variable Immunodeficiency (CVID) is an antibody deficiency that leaves the immune system unable to defend against bacteria and viruses, resulting in recurrent and often severe infections.

The exact cause and genetic inheritance pattern of CVID is unknown in most cases. Both males and females are affected. It is one of the most common forms of primary immunodeficiency disease (PIDD), and the severity of symptoms varies from one person with the disease to another.

CVID can be associated with autoimmune disorders that affect other blood cells causing low numbers of white cells or platelets, anemia, arthritis and other conditions.

People with CVID are also at an increased risk for certain cancers.

CVID Symptoms & Diagnosis

Symptoms CVID can be diagnosed anytime from childhood through adulthood.

As with other antibody deficiencies, the most common types of recurrent infections involve the ears, sinuses, nose, bronchi and lungs. These include: Pneumonia Sinusitis

Ear infections Gastrointestinal infections

Recurrent pneumonia and chronic infections in the lungs can lead to lung damage called bronchiectasis, which can complicate treatment.

Diagnosis CVID may be suspected in children or adults with a history of recurrent infections involving the lungs, bronchi, ears or sinuses.

An accurate diagnosis can be made through screening tests that measure immunoglobulin levels or the number of B cells in the blood.

CVID Treatment & Management

CVID is treated with immunoglobulin replacement therapy (IRT), which most often relieves symptoms. IRT treatments must be given regularly and are life-long.

Antibiotics are used to treat most infections that result from CVID though patients may need treatment for a longer duration than a healthy individual.

DiGeorge Syndrome (DGS)

DGS Overview

DiGeorge Syndrome (DGS) is a primary immunodeficiency disease (PIDD) associated with susceptibility to infections due to poor T cell production and function. DGS is caused by abnormal cell and tissue development during fetal growth. In addition to possible immune system problems, this abnormal development can result in altered facial characteristics, abnormal gland development or defects in organs such as the heart.

While DGS is a lifelong condition, it mostly affects infants and children.

Depending on the severity of the syndrome, recurrent infections tend to decrease in late childhood and adulthood. Still, approximately one-third of affected adults will have mild recurrent infections.

Children with DGS differ in the organs and tissues affected, as well as in the severity of the disease.

Most cases result from a deletion of chromosome 22q11.2 (the DGS chromosome region). A small number of cases of DGS have defects in another chromosome, notably 10p13.

Some people with DGS are susceptible to infections due to poor T cell production and function. T cells are white blood cells that are important for protection against infections.

DGS Symptoms & Diagnosis

Symptoms Certain facial features are often seen with DGS - low set ears, underdeveloped chin, a short philtrum (the vertical groove on the upper lip), a bulbous nose tip, heavy eyelids and/or a small mouth.

Nasal-sounding speech can occur when a cleft palate is involved. Short stature, learning difficulties or certain psychiatric disorders are also common.

Based on which organs are affected by the syndrome, other symptoms may include: Frequent infections Low calcium levels Heart defects

Diagnosis DGS is often diagnosed at birth or in infancy based on clinical observation of multiple symptoms with various organs. A genetic test is used to confirm the diagnosis.

DGS Treatment & Management

As the organs and tissues involved and the severity of the abnormalities vary, treatment plans for DGS must be personalized.

For instance, mild T cell problems can often be managed with antibiotics and close follow-up. On the other extreme, cases of DGS in which T cell development is severely affected have been successfully treated with bone marrow or thymus transplant.

Severe problems involving the heart or facial features may require corrective surgery.

Children with DGS benefit from a multi-specialty approach to treatment, since this disease can be associated with a spectrum of disorders that fall under varying different medical specialties including ENT, immunology, cardiology, genetics and speech therapy.

Selective IgA Deficiency

Selective IgA Deficiency Overview

Selective IgA Deficiency is the most common primary immunodeficiency disease (PIDD). People with this disorder have absent levels of a blood protein called immunoglobulin A (IgA). IgA protects against infections of the mucous membranes lining the mouth, airways and digestive tract.

Although individuals with Selective IgA Deficiency do not produce IgA, they do produce all the other kinds of immunoglobulin. This is why many people with IgA deficiency appear healthy or only have mild reoccurring illness such as gastrointestinal infections.

A common problem in IgA deficiency is susceptibility to infections. A second major problem in IgA deficiency is increased occurrence of autoimmune diseases. Also, many people with Selective IgA Deficiency also have allergies or asthma.

Selective IgA Deficiency Symptoms & Diagnosis

The most common symptom of Selective IgA Deficiency is susceptibility to infections including: Pneumonia Sinusitis Ear infections Chronic diarrhea caused by gastrointestinal infections

IgA deficiency may also cause autoimmune disease, in which the immune system attacks itself. Common examples of these diseases are rheumatoid arthritis and lupus.

Diagnosis requires blood screening to show an IgA deficiency but normal levels of other immunoglobulins.

Selective IgA Deficiency Treatment & Management

The underlying cause for Selective IgA Deficiency is unknown and there is currently no way to replace IgA in the body.

Unlike many other immunoglobulin deficiencies, the condition is not treated with immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

In cases where recurrent infections are a problem, preventative antibiotics may be used to help diminish the frequency of infections. Individuals with IgA deficiency often require a longer course of antibiotics for infections to clear up.

Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID)

SCID Overview

Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) is a rare, inherited condition resulting in a weak immune system that is unable to fight off even mild infections. It is considered to be the most serious primary immunodeficiency disease (PIDD).

SCID is caused by a genetic defect that affects the function of T cells. Depending on the type of SCID, B cells and NK cells can also be affected.

These cells play important roles in helping the immune system battle bacteria, viruses and fungi that cause infections.

Symptoms of the disease are frequently first noticed very early in life. Infants with SCID often suffer from recurrent, severe respiratory infections. These infections are usually serious and may even be lifethreatening. Still, it may require several hospitalizations before SCID is diagnosed.

There are several forms of SCID. The most common type is linked to a problem in a gene on the X chromosome, affecting only males. Women may carry the condition, but they also inherit a normal X chromosome. Men, on the other hand, have only one X chromosome.

Other forms of SCID are caused by a deficiency of the enzyme adenosine deaminase (ADA) and a variety of other genetic defects.

SCID Symptoms & Diagnosis

Symptoms In addition to frequent and often very severe respiratory infections, other symptoms of SCID in infants include poor growth, rashes that look like eczema, chronic diarrhea and recurrent thrush in the mouth, although all of these symptoms may not be present.

Often, SCID is associated with recurrent viral infections and causes several hospitalizations before it is discovered.

One unusual infection that can be present with SCID early on is pneumocystis pneumonia. Presence of this infection is a red flag for the need to evaluate the immune system for SCID.

Diagnosis Early detection of SCID is extremely important. Treating the disease in the first months of life offers a very positive success rate in helping to combat SCID.

Learn about the IDF newborn screening initiative and view a United States map indicating where each state is in terms of newborn screening.

As with other PIDD, screening tests can measure blood lymphocytes levels. A diagnosis of SCID can be made in utero, which is especially helpful if there is a family history of immunodeficiency diseases.

SCID Treatment & Management

The only cure currently and routinely available for SCID is bone marrow transplant, which provides a new immune system to the patient. Gene therapy treatment of SCID has also been successful in clinical trials, but not without complications.

Research on gene therapy for SCID is continuing and may one day be a good option. If you think your child may have SCID, prompt evaluation by an immunology specialist is crucial for early treatment.

Other forms of combined immunodeficiency can occur that may not require bone marrow transplantation.

X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia (XLA)

XLA Overview

X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia (XLA) is an inherited immunodeficiency in which the body is unable to produce the antibodies needed to defend against bacteria and viruses.

Frequently called Bruton's Agammaglobulinemia, XLA is caused by a genetic mistake in a gene called Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase (BTK), which prevents B cells from developing normally. B cells are responsible for producing the antibodies that the immune system relies on to fight off infection.

The most common bacteria causing infection in XLA are Streptococcus, Staphylococcus and Haemophilus.

XLA Symptoms & Diagnosis

Symptoms XLA often becomes apparent in infancy due to recurrent and severe bacterial infections including: Ear infections Sinusitis Pneumonia Diarrhea due to a parasite called Giardia

When a baby is first born, it is protected from infection by IgG antibodies that are passed through the placenta from the mother. This maternal IgG only lasts for several months, and then the infant needs to start producing antibodies on its own. When affected by XLA, the infant cannot do this on his own, and becomes susceptible to these recurrent infections.

Diagnosis XLA can be detected through screening tests that measure immunoglobulin levels or the number of B cells in the blood.

XLA Treatment & Management

There is no cure for XLA, but the condition can be successfully treated. Immunoglobulin replacement therapy is a life-long and life-saving treatment that restores some of the missing antibodies. In addition, some people benefit from a daily course of oral antibiotics to prevent or treat infections.

Most individuals with XLA who receive immunoglobulin on a regular basis can lead relatively normal lives.

Live viral vaccines, such as those for polio, measles, mumps or rubella, are not considered safe for people with XLA. Though rare, these vaccines can infect the recipient with the very disease they were intended to prevent. This is true for most B and T cell immune defects.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Viral DiseasesDocument35 pagesViral DiseasesDivya SoundarajanNo ratings yet

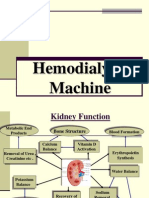

- Hemodialysis Machine12Document45 pagesHemodialysis Machine12Divya SoundarajanNo ratings yet

- ECE 301 - Digital Electronics: Flip-Flops and RegistersDocument36 pagesECE 301 - Digital Electronics: Flip-Flops and RegistersDivya SoundarajanNo ratings yet

- Someone You Know Has MS: A Book For FamiliesDocument19 pagesSomeone You Know Has MS: A Book For FamiliesDivya SoundarajanNo ratings yet

- Addressing Modes of 8085Document10 pagesAddressing Modes of 8085etfs4indiaNo ratings yet

- BmiDocument3 pagesBmiDivya SoundarajanNo ratings yet

- Mathematics 1 QB - PART - ADocument6 pagesMathematics 1 QB - PART - ADivya SoundarajanNo ratings yet

- Datis KharrazianDocument25 pagesDatis Kharraziangreym111100% (1)

- HashimotoDocument9 pagesHashimotoFrinkooFrinkoBNo ratings yet

- Vanderlugt 2002Document11 pagesVanderlugt 2002Hashem Essa QatawnehNo ratings yet

- Urticaria: Collegium Internationale Allergologicum (CIA) Update 2020Document13 pagesUrticaria: Collegium Internationale Allergologicum (CIA) Update 2020Ihdinal MuktiNo ratings yet

- The Lymphatic System and Body Defenses: Part BDocument67 pagesThe Lymphatic System and Body Defenses: Part BJovelle AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Immunotolerance and Autoimmune DiseasesDocument37 pagesImmunotolerance and Autoimmune DiseasesmulatumeleseNo ratings yet

- Autoimmunity and DisordersDocument54 pagesAutoimmunity and DisordersInjamam ul hossainNo ratings yet

- CK-12 Biology Chapter 24 WorksheetsDocument32 pagesCK-12 Biology Chapter 24 WorksheetsShermerNo ratings yet

- Warm Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia: Advances in Pathophysiology and TreatmentDocument8 pagesWarm Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia: Advances in Pathophysiology and TreatmentMishel PazmiñoNo ratings yet

- PD2Document15 pagesPD2DrShobhit RajNo ratings yet

- SerologyDocument33 pagesSerologyGEBEYAW ADDISUNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology Examination AnswersDocument205 pagesPathophysiology Examination AnswersFırat Güllü67% (6)

- International Journal of Immunology and Immunotherapy Ijii 9 064Document5 pagesInternational Journal of Immunology and Immunotherapy Ijii 9 064jongsu kimNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Multiple Sclerosis in Adults Uptodate3Document11 pagesEpidemiology and Clinical Features of Multiple Sclerosis in Adults Uptodate3Régulo RafaelNo ratings yet

- Medical AbbreviationDocument76 pagesMedical AbbreviationNajwa AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Autoimmune DiseasesDocument26 pagesAutoimmune DiseasesCherry Reyes-PrincipeNo ratings yet

- Microbiology: A Systems Approach, 2 Ed.: Chapter 16: Disorders in ImmunityDocument76 pagesMicrobiology: A Systems Approach, 2 Ed.: Chapter 16: Disorders in ImmunityJes OngNo ratings yet

- Specific and Non Specific Immmune System: DR Nova Kurniati, Sppd. K-Ai. FinasimDocument88 pagesSpecific and Non Specific Immmune System: DR Nova Kurniati, Sppd. K-Ai. FinasimamaliakhaNo ratings yet

- A Doctor's 4-Step Program To Treat Autoimmune Disease: THE IMMUNE SYSTEM RECOVERY PLAN by Susan BlumDocument65 pagesA Doctor's 4-Step Program To Treat Autoimmune Disease: THE IMMUNE SYSTEM RECOVERY PLAN by Susan BlumSimon and Schuster85% (26)

- Gel Formulation of Drug X Drug and Evaluate Its EfficacyDocument26 pagesGel Formulation of Drug X Drug and Evaluate Its EfficacyPriyanka YadavNo ratings yet

- Carbohydrate Metabolism Disorders Stom 10-11Document61 pagesCarbohydrate Metabolism Disorders Stom 10-11Artem GrigoryanNo ratings yet

- Anti-Inflammatory Injectable SolutionDocument6 pagesAnti-Inflammatory Injectable SolutionminunatNo ratings yet

- Topic 5 - Handbook of Medical Sociology Ch4 - 2Document23 pagesTopic 5 - Handbook of Medical Sociology Ch4 - 2AngellaNo ratings yet

- Rachmat Gunadi Wachjudi's resume and clinical relevance of vitamin DDocument38 pagesRachmat Gunadi Wachjudi's resume and clinical relevance of vitamin DNururrohmahNo ratings yet

- Eponyms SyndromesDocument23 pagesEponyms Syndromestekennn021No ratings yet

- Hemolytic AnemiaDocument1 pageHemolytic AnemiaTeus FatamorganaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Paediatric Autoimmune Hepatitis AIH. ESPGHAN Advice Guide. 2019. Ver1.Document4 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Paediatric Autoimmune Hepatitis AIH. ESPGHAN Advice Guide. 2019. Ver1.Carmen OpreaNo ratings yet

- Th1 - Th2 Dominance SymptomsListDocument3 pagesTh1 - Th2 Dominance SymptomsListikuus123No ratings yet

- Diabetes Ebook:Type 1 Diabetes in AdultsDocument88 pagesDiabetes Ebook:Type 1 Diabetes in AdultsHealthCare0% (1)

- Immunotoxicology EvaluationDocument38 pagesImmunotoxicology EvaluationVlad TomaNo ratings yet