Professional Documents

Culture Documents

War of The Welles PDF

Uploaded by

Patrick LeeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

War of The Welles PDF

Uploaded by

Patrick LeeCopyright:

Available Formats

War of the Welles, a new documentary by R.H.

Greene for Southern California Public Radio 2013

INTRODUCTION While almost every other byproduct of the "golden age" of American radio drama has been forgotten, The War of the Worlds, from Orson Welles Mercury Theatre, is still broadcast today, 75 years later, all over the world. We remain fascinated not only because of the broadcast's dramatic impact, but because of the story behind the story. By sending terrified masses into the streets, convinced a Martian attack had been launched, the Mercury Theatres War of the Worlds taught us something deeply disturbing about ourselves: that no matter how sophisticated the tools of communication become, the trust we place in them and the limitations of human perception can make people believe just about anything. Myths and legends have accrued around this mythic and legendary broadcast from the start. Now, Southern California Public Radio and documentarian R. H. Greene separate fact from fancy, with a fresh look at a classic called War of the Welles. ACT ONE Halloween morning, 1938. The year's scariest holiday isn't even underway, but it's already been trumped in the fear department. Last night, on Halloween Eve, Orson Welles directed a live radio adaptation of HG Wells' The War of the Worlds, science fiction's first epic about invaders from Mars, published in 1898. To freshen it up, Welles and his collaborators presented a portion of their broadcast as bogus news bulletins, mapping the invasion's destructive path.

By the next morning, all hell has broken loose. You can hear it in Welles' voice. The magnificent bass-baritone that will soon come to dominate the entire medium of the radio drama has gone flutish. Adenoidal. Welles: When I left the broadcast last night, I went into dress rehearsal for a play thats opening in two days, and Ive had almost no sleep. And I know less about this than you do. Reporter: Were you aware of the terror? Welles: Oh, no. Of course not. We did Dracula and I had high hopes that people would react as they would at a movie. Naturally, we will have to sit down and think very carefully about future broadcasts. For all his already vast accomplishments, the Orson Welles of 1938 is still a precocious 23 year old man-child, one who has been a working showbiz professional from the age of 16. It will be said -- forever after and somewhat inaccurately -- that Orson Welles and his Mercury Theatre on the Air have just terrorized an entire country. What is apparent, as Welles faces a hostile press corps on the cold grey morning after the War of the Worlds broadcast, is that Orson Welles has just frightened himself. This documentary is not, as an Edward R. Murrow broadcast labeled it twenty years later, the story of "the night America trembled." It is instead a sort of Frankenstein story. The tale of a mad genius who inadvertently assembles a monster out of discarded bits and pieces. Welles and his collaborators, many of whom you are about to meet, surely pilfered a grave or two in creating their War of the Worlds. But the key difference between Victor Frankenstein and George Orson Welles is this: in building his nightmare creation, Welles frequently carved parts off himself. On April 11, 1937, 18 months before the Mercury War of the Worlds broadcast, radio listeners heard these lines:

You! Are you free? Will you fight? There are still inches for fighting! There is still a niche in the streets! You can stand on the stairs and meet him! You can hold in the dark of a hall! You can die! These lines are from The Fall of the City, an original anti-fascist radio play by poet Archibald MacLeish, was only the second credited broadcast of Orson Welles' long radio career. No less an authority than legendary CBS founder William Paley would later cite The Fall of the City as a pivotal event in the rise of Orson Welles. "The play was a sensation," Paley wrote fifty years later, "which helped point the way to what radio could achieve. It also made the actor, Orson Welles, an overnight star." Much of The Fall of the City is in verse, courtesy of MacLeish, a poet and dramatist with whom Welles has already worked in the theatre. But the framing device, meant to lend currency and urgency to a portentous work, is to use an actor playing a newsman to present events as if they're actually happening. That actor is Orson Welles. With its tone of slowly escalating terror, Welles' performance is of a piece with the ersatz newscasts used so masterfully in the Mercury War of the Worlds. Welles apocalyptic description of the slow, armored approach of The Fall of the Citys fascist superman eerily anticipates the Mercury's reportage of Martian death machines. No one mistook The Fall of the City for anything other than a radioplay. But it was an important stylistic precursor to The War of the Worlds, and Welles' central role in The Fall of the City broadcast makes it likely he remembered the show for at least the next year and a half. Then again, few entertainers have seen as hectic an interval as Welles' next 18 months. And there was another program at least as pivotal as The Fall of the City in making Welles a radio star: The Shadow, one of the Mutual

Broadcasting Network's flagship programs, an energetic crime melodrama with deep roots in the world of pulp fiction. It arrived on radio in 1930 as a spooky anthology program hosted by a cackling, omniscient narrator. In September 1937, Mutual recast the lead, and brought the Shadow into conformity with his pulp fiction persona as a prototypal comic book superhero: a millionaire playboy by day Lamont Cranston - and a cold-hearted vigilante by night the Shadow. The Shadow was Batman before there was Batman--without the cowl, but with a sort of superpower: a kind of mental telepathy rendering the Shadow invisible to his enemies. To add to the air of mystery, the actor playing the new vigilante version of the Shadow remained anonymous for six months . But on May 20, 1938 --163 days before the War of the Worlds broadcast, the mask was pulled off at last, when the Mutual announcer intoned, And now ladies and gentlemen, that interesting message we promised you. The part of Lamont Cranston in The Shadow has been played by one of the most distinguished figures in the theatre today, Mr Orson Welles. Till this moment and nevermore again, anonymity has been a key ingredient in the rise of Orson Welles. As a man of the theatre, a filmmaker and a radio producer, Welles repeatedly gave the impression of springing up like Athena, fully formed and armed for battle, whenever he addressed a new creative medium. But there were crucial and unheralded apprenticeship periods in every instance. In radio, where a great voice was worth its weight in Blue Coal, Welles became found entry as a busy and uncredited journeyman almost from his arrival in New York in December, 1934. The easy camaraderie Welles encountered would prove crucial to his development as a sonic artist, and pivotal to The War of the Worlds. He was a working actor in radio, which meant that he might do several or even several dozen shows in the course of a week. This work that he did in radio was not only often uncredited but unheralded. He was just one figure in a large pool of talent that

worked on everything from soap operas to prime time dramatic shows. -- Radio historian Leonard Maltin. Welles first radio job came in 1935 as an anonymous player on The March of Times, a show that greatly influenced War of the Worlds. Where War of the Worlds was a radio drama done as news of the day, The March of Time was news of the day, done in the style of a radio narrative. As Welles remembered in his 1973 film F for Fake, Welles was hired by Paul Stewart for The March of Time, and Stewart became a pivotal figure in the Mercury broadcasts. Welles said Paul was a real capo mafia in the Martian caper. Maltin says Stewart was a versatile actor who also apparently functioned as Orsons rehearsal director for the weekly Mercury broadcast. Orson would be busy with six other things, and so Paul Stewart would run the actors through their lines, and do his best to second guess Orson until the last minute sometimes sometime the very last minute -- and then Orson would step in and do the final directing, and often change what Stewart had come up with, but at least he had something to work with, a solid first draft. But Stewart wasnt the only far from the only core member of the Mercury assembled out of pieces of Orson Welles fragmentary radio career. Agnes Moorehead found fame as Margot Lane, the Shadow's Girl Friday. Welles adored her. And she would later attain screen immortality under his direction in Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons. Ray Collins, a top radio star, worked with Welles on The March of Time and then became a critical player in nearly every incarnation of the Mercury Theatre on the Air, including Welles wartime propaganda shows, and his doomed attempt at a comedy variety program. Their professional relationship lasted twenty years. March of Time was just one program in a radio schedule so busy Welles allegedly hired an ambulance to drive him, with sirens blaring, from job to job. Welles was a fast learner, and as he bounced from studio to studio, he experienced every genre, director, actor,

conductor and sound effects artist in Manhattan. He enjoyed himself immensely, but he was also forging an aesthetic, gauging what techniques worked best -- for him, and for radio. By 1937, Orson Welles had spoken into nearly every microphone in New York. And he had learned every lesson a great medium at a high watermark could teach him. All that remained were the lessons he was about to teach Radio itself. ACT TWO The Mercury Theatre on the Air took its name from the theatre company Welles launched in 1937 with his collaborator John Houseman. The volatile Welles/Houseman producing partnership was one of the most storied in theatre history. Their all-black Macbeth was set in a seething post-colonialist Haiti. Their anti-Fascist Caesar wore the modern dress of Mussolini's Italy. For audiences, it was as if warhorse classics were written again, in lightning. Mercury member George Coulouris, told actor Astor Sklair in 1978, It was a time of fascism. And it seemed to be in tune with the period. Welles was immediately acclaimed as a genius for his direction and playing the part of Brutus. Depending on whose stories you believed, Houseman was either the leveling influence, who tried to keep show on time, on budget, and on point, or a thorn in Mr. Welles side. Id imagine the truth was between those two extremes. -- Radio historian Leonard Maltin. Almost singlehandedly, Welles and Houseman popularized what came to be called "concept' production, where a director violently alters a text's setting, casting and even the lines themselves to make radical new statements. And recasting The War of the Worlds, British Victorian science fiction, into the context of American news radio would make The War of the Worlds the biggest Welles/Houseman "concept production" of them all.

In a 1988 interview for the audio documentary Theatre of the Imagination, Mercury actress Geraldine Fitzgerald gave perhaps the most eloquent description of the Welles/Houseman creative codependency. He was like a busted water main, his talent, Fitzgerald said. It went all over the streets and down alleys, and filled up holes and made shapes and patterns. That was Orson. Then, John comes along and then with buckets and jugs and pots and pans he collects all this wonderful, wonderful material, and allows it to have more shape than perhaps Orson would have bothered to give it. But he had too much talent to be careful with it. By 1936, Welles was earning gold rush money as an anonymous radio actor. But his name was becoming legendary on the New York stage, and synonymous for daring. It was that Orson Welles -- the stage innovator, and enfant terrible -- CBS hired to produce a live weekly radio show. The hyperbolic opening of the first Mercury broadcast -- Orson Welles has come to be the most famous name of our time in American drama. -- conveyed New York's intoxication with Welles to a national audience unfamiliar with him. As Welles told the New York Times, experimentation was the Mercury's brief. "The Mercury has no intentions of reproducing its stage repertoire in these broadcasts," Welles said. "We plan to bring to radio the experimental techniques that have proven so successful in another medium, and to treat radio itself with the intelligence and respect such a beautiful and powerful medium deserves." June 12, 1938. 140 days before the War of the Worlds broadcast. The Mercury company hit the airwaves July 11 in a program initially called First Person Singular, a nod to Welles "key man" status. This first Mercury broadcast is the only one Welles mentions by name in his famous post-War of the Worlds news conference, and for good reason: It is Dracula. Bram Stoker's vampire tale is a collage of diary entries, letters between characters, and yes, even news reports and telegrams. It strives on the page for documentary realism, and in that way is a precursor to the Mercury War of the Worlds.

By a quirk of programming, Welles is almost entirely free to create his little weekly masterpieces. His show is unsponsored and in Welles' era of broadcasting, "unsponsored" means all but unsupervised. It may be difficult to understand because its so different from the way television is run today, Leonard Maltin says, but in those days the programming was controlled by the sponsor. When a network had time to fill, and no sponsor, the network had to produce a show of its own. On September 11, 1938, the Mercury comes very close to the structural premise of its War of the Worlds while adapting its Caesar stage show for radio. You cannot adapt Shakespeare as realistic sounding news bulletins-the heightened vocabulary and rolling iambic pentameter refuse to take the shape. But on a one hour show, the Bard needs compressing. So Welles had gave the links to H. V. Kaltenborn, radio's leading political commentator, throw the action back and forth from Brutus to Caesar to Antony, just as Kaltenborn would soon bridge stories of Hitler, FDR and Hirohito after the outbreak of World War II. Chaos was an essential precondition of Welles' process. Struck by a new idea, he always pursued it. For the exacting and precise John Houseman, it was maddening. There was a time when I never got out of bed, because I never had time to get out of bed, he said in Theatre of the Imagination, So I would lie in bed and administer the Mercury Theatre because I had no time to get up. As a buffer, Houseman hired Howard Koch, a struggling playwright with no radio experience who came to Houseman's attention through the Federal Theatre Project. The War of the Worlds was Koch's third Mercury broadcast. I stopped at a gas station, they gave me a Jersey map, and I spread the map out, closed my eyes, put the pencil down, landed on Grovers Mills. Well, I thought, it has a good sound. American, and real. -- Howard Koch, NPR, 1988.

Koch would have less than a week to deliver his 60-page War of the Worlds radio play. Though he demanded script changes, Welles was something of an absentee landlord that week. He was engaged, round the clock, in rehearsing a Mercury stage show. But Welles input was still crucial, and even his absence proved critical. Presented with Paul Stewart's rehearsal recording at mid-week, Welles and his dejected radio troupe concluded the script was a turkey--corny and improbable. The machine had malfunctioned in Welles absence. It needed his electricity. It would have to settle for his notes. Welles told Koch to fragment the action with more bulletins, Paul Stewart to work harder on the sound effects. Maybe they could bluff their way out. We must consider now the formidable figure of Welles the radio director. The Mercury productions are frequently praised as innovative, but rarely examined much beyond the musical contributions of show composer Bernard Herrmann and Welles striking use of overlapping voices. The Mercury broadcasts are, in fact, symphonic in construction, and this is rooted in Welles formative creative experiences, which were musical. A child prodigy first profiled in a Wisconsin newspaper article titled "Cartoonist, Actor, Poet -- And Only Ten!," Welles was raised to be a concert pianist and painter by his mother, Beatrice. Welles' mother died just four days after his ninth birthday. He set aside the piano; he would remain an amusing caricaturist to the end of his life. But if Welles didn't have a musician's fingers, he had a musician's ear. On radio, Welles is always searching for the sonic element that communicates mood or psychology, to act as a kind of score. In the Mercury's non-fiction masterpiece "Hell on Ice," he uses wind -- a stock radio effect -- to strangle the prayers of a doomed arctic expedition. Manipulated realism was fundamental to Welles' approach, and could have unintended consequences. His first important pre-Mercury radio

production was a massive adaptation of Les Miserables, and to change the sonic palette, Welles ran a live microphone into the echoey mens room. The predictable accident came at about seven minutes into Episode One, when a squeaking stall door announces what is very likely radio's first toilet flush. Welles directed his shows from the studio -- an unheard of placement for a radio man, but one maestro Bernard Herrmann would have recognized. In photos taken during live Mercury broadcasts, his posture is unmistakable. Orson Welles didnt direct radio shows the way most of his colleagues did, Maltin says. Most of them were behind soundproof glass in the control room. None of that for Orson. He stood on a podium, like a conductor, in the studio, with his ensemble. The energy of the broadcasts, their animal vigor, flowed from Welles into the ensemble as from Leonard Bernstein's baton to the New York Phil. In that sense, the Mercury broadcasts are shared achievements that are also uniquely personal works. And the realism of the War of the Worlds broadcast is central to Welles aesthetic. He's a magician at heart--he wants to make the audience believe the illusion, in order to leave them stunned and gasping when the twist comes. ACT THREE Radio was the only medium that imposed a discipline that Orson would recognize. And that was the clock. He knew every week that clock was ticking. That red light would come on and say, On the Air." -- Richard Wilson to Frank Beacham, Theatre of the Imagination, 1988 October 30, 1938. 8 pm Eastern. Zero hour. The War of the Worlds broadcast begins with a brief disclaimer explaining clearly its a Mercury Theatre adaptation of the H.G. Wells novel. This saved Welles' career once the lawsuits started to fly.

Then comes Welles in omniscient narrator mode, his bread and butter radio role, giving the setup. Its followed by generic dance music, badly performed, supposedly by Ramon Raquelo and his orchestra, but its really the great Bernard Herrmann, under protest, in what Paul Stewart recalled as "one of the most hilarious musical moments in radio history." But listeners just tuning in have already missed the disclaimer. To their ears, its just one more mediocre music show. The band plays "Stardust," an inside joke. Then comes a news bulletin. Then another. At this time in the 1930s, Leonard Maltin says, There were increasing numbers of live news broadcasts. The Hindenburg disaster, Hitler marching through Europe. People were conditioned to believe what they heard on the radio. Next, a reporter speaks to an expert who sounds like Orson Welles, and then we learn theres a meteorite in New Jersey. The newsman traverses 10 miles in 93 seconds of air time to get to the meteorite. Some listeners keep believing anyway. The newsman is played by Frank Readick, a versatile radio actor. Readick preceded Welles as the Shadow, and stayed with the show to cackle and spout catchphrases when Welles' heroic bass baritone proved wrong for the task. Readick has spent the week listening over and over to reporter Herb Morrison's famed recording of the Hindenburg catastrophe. Readick's mission, to assimilate Morrison's progression from awe to terror to empathetic horror--to feel the recording in his bones. Back at CBS, The Martians show themselves at 8:15pm. And Frank Readick gives the performance of his life as the Martians point a heat ray at the hapless earthlings, and they burst into flame. At this moment, fate intervenes in the form of a wooden dummy. The unsponsored Mercury Theatre exists on CBS largely because of the Chase and Sanborn Hour on NBC. The show, starring ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and his puppet Charlie McCarthy,

commands a staggering 35% of the radio audience, which is why CBS can't find a sponsor for Orson Welles. Like the Mercury, Bergen and McCarthy are celebrating Halloween. Then, 15 minutes into The War of the Worlds, Bergen and McCarthy toss it to Dorothy Lamour, who begins to sing Two Sleepy People. Bored NBC listeners start to channel surf. When they get to CBS, they wake up when they hear newsman Carl Phillipss death on The War of the Worlds. According to a CBS survey, 63% of listeners who tune in after the show began believe it to be true. Meanwhile, CBS is inundated with panicked and angry calls. Telephone exchanges throughout the US start to explode with traffic. CBS Chairman William Paley told NPR in 1988, I wasnt listening to it. I was at home playing cards, and these telephones calls were coming in. I get these calls all the time and Im sick and tired of it. Then I got a call from my office saying a terrible thing has happened. 29 minutes into The War of the Worlds, actor Kenny Delmar is introduced as Secretary of the Interior, performing as a very recognizable President Franklin Roosevelt, in direct defiance of CBS Legal, which excised FDR from the bit, for fear it would seem too real. The lawyers were right. Multiple accounts of the panic will cite "the President" as the man who convinced the listener the Martians had come. Panicked itself now, the network wants to pull the plug on the show. In 1955, for the BBC, Welles remembered the view from the studio floor: About halfway through the show, we saw that in the control room there were a great number of policemen, and every moment more. And we thought, well somethings gone wrong. Some few people have complained and have swallowed what we told them about Martians having come to the world. Unaware of the scope of the crisis, Welles refuses to halt in the midst of what he now realizes is brilliant radio. In the booth, John

Houseman remembered that he physically blocked an anxious CBS underling from entering the studio to stop the show. Then, on the broadcast, Ray Collins climbs onto the imaginary roof of the non-existent Manhattan "Broadcasting Building," and describes the Martians release of poison gas. Sociologist Hadley Cantril, the distinguished sociologist, compiled testimonials of the panic for his 1940 book The Invasion from Mars. When the gas was spreading, I got scared... "I knew it was some Germans trying to gas all of us. Hitler had sent them all!" "We were in as safe a place as possible. The higher you are, the safer you are from the gas!" This phobia is traceable, almost to the second. Gas is not released by the War of the Worlds Martians until 31 minutes into the show, when it wipes out a unit of the National Guard. 8 minutes later, Martian gas pours through Manhattan and takes down Ray Collins, in perhaps the show's most terrifying scene. Many of the listeners who take flight from their homes will wear improvised gas masks. Panic captured them here. Just 55 seconds later, at minute 40 of a one hour show, the spell is broken at last, when CBS takes a station break, re-explaining that its the Mercury Theatres adaptation of the Wells book. But the spell refuses to break. In Theatre of the Imagination, Houseman said, But by then of course, everyone was rushing around, no one was listening. Of all the stories surrounding The War of the Worlds, a key claim is that many millions believed that Martians were actually attacking. In truth, nothing like the entire 99-million population of the US is in a state of panic. But a frightening proportion of it is.

Best estimates give The War of the Worlds an audience of 6 million-double the Mercury's usual numbers, in a show that gained listeners as it ran. Prof. Cantril analyzed two contemporaneous polls, including one by the company we now call Gallup. His conclusion: 1.7 million people believed the broadcast was real, and 1.2 million were frightened by it. Cantril speculates that the other 500,000 believers surveyed were too embarrassed to admit they were frightened by a radio show. Terrified listeners will later sue CBS for damages. The FCC will slap radio's wrists. And the entire industry will impose practices to insure panic won't come to us again. But it will of course. Panic will find George Takei, this program's presenter, interned at age four by the US Government at the start of WW2. I was only one year old in 1938 when The War of the Worlds was broadcast, Takei remembered, but I remember my parents and their friends talking about it. And when you think about how many Americans honestly believed the Martians were invading, its not hard to understand why Americans would just a few years later be so paranoid as to think Japanese American citizens, whod lived here for generations, could suddenly become Americas enemy simply because they happened to look like the people who bombed Pearl Harbor. Then to Howard Koch, and dozens of other Welles' collaborators, blackballed as alleged communists during the McCarthy witch hunts. Panic never really leaves again. It just sleeps. But the immediate effect of the War of the Worlds broadcast on Welles and the Mercury will be to make them household names. And to gain them a sponsor. Campbells Soup. They will get away with it all. Welles played coy for years about whether he meant to incite a national panic. But he was more forthright remembering events for his BBC TV series Orson Welles Sketchbook in 1955. I had no idea

that Id suddenly become a national event. We didnt know it wasnt a few people, (that) it was in fact nationwide. In Theatre of the Imagination, actress Arlene Francis gave an eyewitness account of Welles' attitude when he and Houseman escaped the chaos at CBS and hurried to their theatre for rehearsal, hours late. He said, I dont know whats going to happen. Police are going to be after me. All hell has broken loose now because I did the War of the Worlds so well. The evening ended with a walk by Welles and several Mercury cast members down to Time Square, where the famed Moving News ticker read: "ORSON WELLES FRIGHTENS THE NATION." In light bulb letters 20 feet high. It was already Halloween.

"War of the Welles," a 75th anniversary celebration of the Orson Welles/Mercury Theatre broadcast of "The War of the Worlds," was written, directed, edited and narrated by R. H. Greene, with help from Alana Rinicella; and produced by R. H. Greene and John Rabe for Southern California Public Radio. It was introduced by George Takei. Re-enactments were read by Tim Cogshill, Darroch Greer, Alana Rinicella, and John Rabe. Engineering help from SCPR's Dave McKeever and Doug Gerry, and NPR's New York bureau. For more information, go to kpcc.org/waroftheworlds.

You might also like

- Orson Welles's The Trial Film Noir and The Kafkaesque - J. AdamsDocument19 pagesOrson Welles's The Trial Film Noir and The Kafkaesque - J. AdamsTheaethetus0% (1)

- Best Seat in the House - An Assistant Director Behind the Scenes of Feature FilmsFrom EverandBest Seat in the House - An Assistant Director Behind the Scenes of Feature FilmsNo ratings yet

- Where the Boys Are: Cinemas of Masculinity and YouthFrom EverandWhere the Boys Are: Cinemas of Masculinity and YouthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Prestige Television: Cultural and Artistic Value in Twenty-First-Century AmericaFrom EverandPrestige Television: Cultural and Artistic Value in Twenty-First-Century AmericaNo ratings yet

- Screening the Stage: Case Studies of Film Adaptations of Stage Plays and Musicals in the Classical Hollywood Era, 1914-1956From EverandScreening the Stage: Case Studies of Film Adaptations of Stage Plays and Musicals in the Classical Hollywood Era, 1914-1956No ratings yet

- Playing Lear: An insider's guide from text to performanceFrom EverandPlaying Lear: An insider's guide from text to performanceNo ratings yet

- The Hollywood War Film: Critical Observations from World War I to IraqFrom EverandThe Hollywood War Film: Critical Observations from World War I to IraqRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- “Aren’t You Gonna Die Someday?” Elaine May's Mikey and Nicky: An Examination, Reflection, and Making OfFrom Everand“Aren’t You Gonna Die Someday?” Elaine May's Mikey and Nicky: An Examination, Reflection, and Making OfNo ratings yet

- Perpetual Outsider: An Unofficial, Unauthorised Fan Guide To Doctor Who: Vol 3 1982-1996From EverandPerpetual Outsider: An Unofficial, Unauthorised Fan Guide To Doctor Who: Vol 3 1982-1996No ratings yet

- Kick Ass Production NotesDocument45 pagesKick Ass Production NotesMrSmithLCNo ratings yet

- Magnificent Obsession: The Outrageous History of Film Buffs, Collectors, Scholars, and FanaticsFrom EverandMagnificent Obsession: The Outrageous History of Film Buffs, Collectors, Scholars, and FanaticsNo ratings yet

- Naturals Vol. 1: A Pictorial Essay of Filmed Female IntensityFrom EverandNaturals Vol. 1: A Pictorial Essay of Filmed Female IntensityNo ratings yet

- Other People's Shoes: Thoughts on ActingFrom EverandOther People's Shoes: Thoughts on ActingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Silent Serial Sensations: The Wharton Brothers and the Magic of Early CinemaFrom EverandSilent Serial Sensations: The Wharton Brothers and the Magic of Early CinemaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Transnationalism and Genre Hybridity in New British Horror CinemaFrom EverandTransnationalism and Genre Hybridity in New British Horror CinemaNo ratings yet

- It's All True Orson Welles Pan-American JourneyDocument417 pagesIt's All True Orson Welles Pan-American Journeyleretsantu100% (3)

- Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens: Video Spectatorship From VHS to File SharingFrom EverandKiller Tapes and Shattered Screens: Video Spectatorship From VHS to File SharingNo ratings yet

- CinemaScope 3: Hollywood Takes the Plunge: A Detailed Survey of 164 Wide-Screen MoviesFrom EverandCinemaScope 3: Hollywood Takes the Plunge: A Detailed Survey of 164 Wide-Screen MoviesNo ratings yet

- A Daily Dose of the American Dream: Stories of Success, Triumph, and InspirationFrom EverandA Daily Dose of the American Dream: Stories of Success, Triumph, and InspirationNo ratings yet

- Reform Cinema in Iran: Film and Political Change in the Islamic RepublicFrom EverandReform Cinema in Iran: Film and Political Change in the Islamic RepublicNo ratings yet

- LAUSD Arts BudgetDocument1 pageLAUSD Arts BudgetPatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- I405 80HrClosure MapDocument1 pageI405 80HrClosure MapPatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- LASD - Piquette Weapons IndictmentDocument3 pagesLASD - Piquette Weapons IndictmentPatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- LASD - Visiting Center IndictmentDocument15 pagesLASD - Visiting Center IndictmentPatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- Cicinelli ResponseDocument10 pagesCicinelli ResponsePatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- Trouble in Toyland 2013Document41 pagesTrouble in Toyland 2013Patrick LeeNo ratings yet

- Preventing The Nightmare 2003Document8 pagesPreventing The Nightmare 2003Patrick LeeNo ratings yet

- Text of President Barack Obama's State of The Union AddressDocument14 pagesText of President Barack Obama's State of The Union AddressPatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- Kelly Thomas Amended ComplaintDocument17 pagesKelly Thomas Amended ComplaintPatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- Preventing The Nightmare 2003Document8 pagesPreventing The Nightmare 2003Patrick LeeNo ratings yet

- LASD - Mortgage Fraud ComplaintDocument22 pagesLASD - Mortgage Fraud ComplaintPatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- LASD - Obstruction IndictmentDocument18 pagesLASD - Obstruction IndictmentPatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- CVM Jerky Pet Treats FS 1013Document1 pageCVM Jerky Pet Treats FS 1013Patrick LeeNo ratings yet

- US Residential and Foreclosure Sales Report PDFDocument15 pagesUS Residential and Foreclosure Sales Report PDFPatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- Coliseum Minute OrderDocument1 pageColiseum Minute OrderPatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- Coliseum Decision OrderDocument16 pagesColiseum Decision OrderPatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- Charged Up: Southern California Edison's Key Learnings About Electric Vehicles, Customers and Grid ReliabilityDocument7 pagesCharged Up: Southern California Edison's Key Learnings About Electric Vehicles, Customers and Grid ReliabilityPatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- New $100 Bill DetailsDocument1 pageNew $100 Bill DetailsPatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- H. R. LL: A BillDocument32 pagesH. R. LL: A BillSouthern California Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Powerhouse Fire Map June 1Document2 pagesPowerhouse Fire Map June 1Patrick LeeNo ratings yet

- Covered California: Health Plans & Rates For 2014Document86 pagesCovered California: Health Plans & Rates For 2014Tim McGheeNo ratings yet

- Pasadena Unified School District Free Meal SitesDocument1 pagePasadena Unified School District Free Meal SitesPatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- The Supersizing' The U.S. Catholic Parish LifeDocument4 pagesThe Supersizing' The U.S. Catholic Parish LifePatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- Anaheim Police Department Press Release, May 29, 2013Document1 pageAnaheim Police Department Press Release, May 29, 2013Patrick LeeNo ratings yet

- Integrated Voter EngagementDocument48 pagesIntegrated Voter EngagementPatrick LeeNo ratings yet

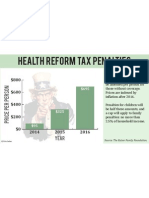

- Health Reform Tax PenaltiesDocument1 pageHealth Reform Tax PenaltiesPatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- Anaheim Police Department Press Release, May 29, 2013Document1 pageAnaheim Police Department Press Release, May 29, 2013Patrick LeeNo ratings yet

- DORNER Dispatch LogsDocument30 pagesDORNER Dispatch LogsGina DvorakNo ratings yet

- KCET Press ReleaseDocument2 pagesKCET Press ReleasePatrick LeeNo ratings yet

- Homologation Form Number 5714 Group 1Document28 pagesHomologation Form Number 5714 Group 1ImadNo ratings yet

- Lantern October 2012Document36 pagesLantern October 2012Jovel JosephNo ratings yet

- Ferret Fiasco: Archie Carr IIIDocument8 pagesFerret Fiasco: Archie Carr IIIArchie Carr III100% (1)

- WSP - Aci 318-02 Shear Wall DesignDocument5 pagesWSP - Aci 318-02 Shear Wall DesignSalomi Ann GeorgeNo ratings yet

- RTS PMR Question Bank Chapter 2 2008Document7 pagesRTS PMR Question Bank Chapter 2 2008iwan93No ratings yet

- RQQDocument3 pagesRQQRazerrdooNo ratings yet

- The 4Ps of Labor: Passenger, Passageway, Powers, and PlacentaDocument4 pagesThe 4Ps of Labor: Passenger, Passageway, Powers, and PlacentaMENDIETA, JACQUELINE V.No ratings yet

- AMU2439 - EssayDocument4 pagesAMU2439 - EssayFrancesca DivaNo ratings yet

- 1 Chapter I Translation TheoryDocument19 pages1 Chapter I Translation TheoryAditya FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- 1995 - Legacy SystemsDocument5 pages1995 - Legacy SystemsJosé MªNo ratings yet

- Fernando Medical Enterprises, Inc. v. Wesleyan University Phils., Inc.Document10 pagesFernando Medical Enterprises, Inc. v. Wesleyan University Phils., Inc.Clement del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Natural Science subject curriculumDocument15 pagesNatural Science subject curriculum4porte3No ratings yet

- January 2008 Ecobon Newsletter Hilton Head Island Audubon SocietyDocument6 pagesJanuary 2008 Ecobon Newsletter Hilton Head Island Audubon SocietyHilton Head Island Audubon SocietyNo ratings yet

- Bullish EngulfingDocument2 pagesBullish EngulfingHammad SaeediNo ratings yet

- Arraignment PleaDocument4 pagesArraignment PleaJoh SuhNo ratings yet

- Destination Management OverviewDocument5 pagesDestination Management OverviewMd. Mamun Hasan BiddutNo ratings yet

- North South University: AssignmentDocument14 pagesNorth South University: AssignmentRakib HasanNo ratings yet

- Visual AnalysisDocument4 pagesVisual Analysisapi-35602981850% (2)

- Legal Aspect of Business Course Outline (2017)Document6 pagesLegal Aspect of Business Course Outline (2017)Sulekha BhattacherjeeNo ratings yet

- Condicional Perfecto Continuo interrogativo guíaDocument2 pagesCondicional Perfecto Continuo interrogativo guíaMaxi RamirezNo ratings yet

- TOTAL Income: POSSTORE JERTEH - Account For 2021 Start Date 8/1/2021 End Date 8/31/2021Document9 pagesTOTAL Income: POSSTORE JERTEH - Account For 2021 Start Date 8/1/2021 End Date 8/31/2021Alice NguNo ratings yet

- Present Tense Exercises. Polish A1Document6 pagesPresent Tense Exercises. Polish A1Pilar Moreno DíezNo ratings yet

- इंटरनेट मानक का उपयोगDocument16 pagesइंटरनेट मानक का उपयोगUdit Kumar SarkarNo ratings yet

- Final Portfolio Cover LetterDocument2 pagesFinal Portfolio Cover Letterapi-321017157No ratings yet

- Cek List in House BakeryDocument20 pagesCek List in House BakeryAhmad MujahidNo ratings yet

- History of Early ChristianityDocument40 pagesHistory of Early ChristianityjeszoneNo ratings yet

- Public Relations & Communication Theory. J.C. Skinner-1Document195 pagesPublic Relations & Communication Theory. J.C. Skinner-1Μάτζικα ντε Σπελ50% (2)

- Terrestrial EcosystemDocument13 pagesTerrestrial Ecosystemailene burceNo ratings yet

- Connotative Vs Denotative Lesson Plan PDFDocument5 pagesConnotative Vs Denotative Lesson Plan PDFangiela goc-ongNo ratings yet

- Mechanics of Solids Unit - I: Chadalawada Ramanamma Engineering CollegeDocument1 pageMechanics of Solids Unit - I: Chadalawada Ramanamma Engineering CollegeMITTA NARESH BABUNo ratings yet