Professional Documents

Culture Documents

My TBR Saraf

Uploaded by

gjuiolpOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

My TBR Saraf

Uploaded by

gjuiolpCopyright:

Available Formats

This is the first of a five part series on how to differentiate stroke from inner ear disease in acute vertigo.

The main symptoms of cerebellar stroke (CS) are dizziness, nausea, vomiting, gait instability (unsteadiness while walking) , and headaches. This presents some difficulty because these symptoms are most often associated with common benign disorders such as migraine or peripheral vestibular (inner ear) disease. Differentiation between these benign disorders and cerebellar stroke (CS) can be aided by quick and simple examination including evaluation of control of eye movements, presence and pattern of nystagmus ( an involuntary rhythmic eye movement), and examination of gait and coordination (more on that later). Stroke and TIA (transient ischemic attack) account for approximately 3% of dizziness complaints in the Emergency Department. Cerebellar strokes (CS) are uncommon and account for only 3% of all strokes. When the complaint of dizziness is isolated (e.g. no additional neurological complaints) stroke and TIA are responsible for less than 1% of patients with dizziness (Kerber, et al., 2006). The average age of CS patients is 65 years, with two-thirds being male. Risk factors for CS are similar to those associated with other stroke, and include: hypertension, diabetes, cigarette smoking, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, and history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (Edlow, NewmanToker, & Savitz, 2008). Consequences of CS include death and permanent disability (Savitz, Caplan, & Edlow, 2006). Retrospective studies of misdiagnosis of Cerebellar Stroke (CS) reveal that the most common medical errors include failure to perform appropriate screening exams, choosing a diagnosis that does not explain all the presenting symptoms, failure to consider CS as a differential diagnosis based on the patients age, and the ordering of the inappropriate neuro-imaging study . When the risk factors, symptoms and clinical signs suggest the possibility of cerebellar or brainstem infarction, specific neuro-imaging (CT or MRI scanning) can help verify this suspicion, but are pretty poor at ruling them out. Imaging Patients presenting with dizziness and vertigo are often referred for Computerized Tomographic (CT) scan of the brain. CT scans are frequently normal in the first few hours following acute ischemic stroke, therefore, a normal CT scan cannot rule out CS. As many as 50% to 74% of CS patients may be missed if the diagnosis is dependent on CT scanning (Simmons, Biller, Adams, Dunn, & Jacoby, 1986; Chalela et al., 2007). CT studies are particularly poor for ruling out brainstem stroke as that area is often poorly visualized due to surrounding bone structures. The American College of Radiology recommends MRI of the head without and with contrast as the appropriate test for the complaint of vertigo with no hearing loss (ACR, 1996). Although MRI has significantly higher sensitivity than CT, the examiner must not rely totally on MRI findings to identify or rule out cerebellar stroke. Twelve percent of CS patients had normal MRI exams on initial presentation, with abnormal exams a few days later (Kattah et al. 2009). Similarly, Chalela et al. (2007) report that 17% of patients diagnosed with acute stroke had normal MRI exams on initial presentation, commenting that there is a higher likelihood of a false-negative MRI exam when the stroke is located in the brainstem. So the old adage, Lets get an MRI just to be sure, isnt such a sure bet after all. Because of the low incidence of dizziness caused by Cerebellar Stroke (CS), as well as the increased cost and reduced availability of MRI scanners, screening protocols to determine which patients require MRI scanning should be developed and followed in both Emergency Departments and primary care settings. David Solomon, a noted neurologist at Johns Hopkins University, offers the following suggestions: Note: The items in quotes are from Dr. Solomon, the additional comments are mine (ALD).

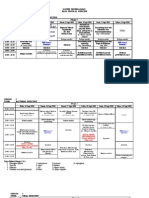

A patient presenting with acute vertigo should be referred for emergent neuro-imaging (MRI) when accompanied by: 1. Unilateral or asymmetrical hearing loss Unilateral hearing loss may be the result of labyrinthine disorders such as Menieres disease or labyrinthitis, but may also be the result of vestibular schwannoma or infarction of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA). 2. Brainstem or cerebellar symptoms other than vertigo 3. Stroke risk factors (diabetes, hypertension, history of Myocardial Infarction). 4. Acute onset associated with neck pain Neck pain associated with vertigo is considered a sign of possible vertebral artery dissection . 5. Direction changing spontaneous nystagmus Additionally, nystagmus that are vertical or do not diminish with visual fixation suggest central involvement. 6. New onset severe headache Migraine is known to cause episodic vertigo accompanied by headache, however, Migraine patients typically have a history of prior headache . 7. Inability to stand or walk This is often the most obvious clinical sign differentiating the patient with acute labyrinthine vertigo from a patient with cerebellar or brainstem stroke. Even the most severely vertiginous labyrinthine patient can typically walk a few steps. If the patient cannot stand or walk unassisted, stroke should be suspected . This checklist is something I came up with at the suggestion of a local family practice physician that said, Can you give me a checklist of the things I should be looking for, with management recommendations? A word of caution, this checklist is currently just an idea and has not been validated in any way. Since the sensitivity and specificity of categorizing a patient as peripheral versus central is greatly increased when the screening tests are viewed in combination, it is helpful to use a checklist. As you view the checklist will note two columns. The column on the left represents findings considered to be highly specific to peripheral vestibular (labyrinthine) disorders. The column on the right represents physical signs associated with brain stem or cerebellar dysfunction. As the screening exam is carried out, the examiner should mark the appropriate box. If the examiner finds that items on the left are marked, and the right column is unmarked, it is highly likely that the patient suffers from a peripheral labyrinthine disorder. To a large degree, a brain stem or cerebellar pathology has been effectively ruled out by identifying that the patients complaints are most likely of peripheral labyrinthine origin. Conversely, if any of the physical signs listed in the right column are noted, brain stem or cerebellar stoke should be investigated by neuro-imaging or neurologic consultation. Physical findings in the left column suggest peripheral labyrinthine etiology. Findings in the right column suggest cerebellar or brain stem etiology. Note: My apologies for the formatting below. The columns should be side by side., but I am posting this on Memorial Day and decided not to bother the IT folks. You get the idea. A properly formatted checklist can be found in my new book on page 58. Initial Examination Checklist for Vertigo Peripheral versus Central Name _______________________________________________ Date ___________________ Equivocal No nystagmus Peripheral Central

Direction Fixed Nystagmus Nystagmus decrease w/ fixation Ambulates unassisted Positive Head Thrust exam Headshake nystagmus Transient Positional Nystagmus (positive Dix-Hallpike) Direction Changing Nystagmus No decrease w/ fixation Ataxia unable to walk unassisted Ocular Misalignment Vertical Skew Deviation Focal Neurologic Deficit (hemiplegia, dysarthria, limb ataxia) New Onset Severe Headache Refer for vestibular exam Refer for Neuro-Imaging Refer for Neurologic Consult HINTS to diagnosing cerebellar stroke A simple eye exam more sensitive than MRI? Part VFinal Installment Kattah et al. (2009) describe a bedside eye movement exam thought to be very sensitive in differentiating acute vertigo patients with CS from those with peripheral vestibular disorders. The brief exam includes a combination of Head Impulse (Head Thrust) testing as described below, a review of nystagmus pattern , and examination for ocular misalignment (vertical skew deviation) using the cross cover test. The cross cover test involves having the patient look at an object in the distance, then alternately covering each eye. If there is a consistent eye movement to regain fixation on the object, then ocular misalignment is suspected. Some physicians use a Maddox Rod to

provide a more objective evaluation of ocular misalignment.

This combination of eye exams, described asHINTS (Head Impulse test - Nystagmus Test ofSkew) is reported to be more sensitive than MRI in early identification of CS. Head Thrust testing is almost always positive in patients with acute vertigo of labyrinthine origin, and almost always (approximately 90%) negative in patients suffering vertigo related to CS. Direction changing horizontal nystagmus is sometimes (approximately 20%) present with CS, but nystagmus is almost always direction fixed in acute labyrinthine disorders. Vertical skew deviation (ocular misalignment) is present in some (25%) of CS patients, but very rare (4%) in labyrinthine patients. When a patient presents with the combination of: 1. Normal Head Thrust exam, 2. Direction changing horizontal nystagmus, and 3. Positive Skew Deviation, there is a high probability (100% in the recent study) of brain or brainstem abnormality. Conversely, when this combination of exams is considered benign (e.g. positive head thrust, no nystagmus or direction fixed nystagmus, and negative test for skew deviation) there is a very small chance (4%) of central involvement. This exam has significantly better sensitivity (100% versus 72%), and comparable specificity (96% versus 100%) when compared to immediate MRI (Kattah et al., 2009). Because this exam can be done in one or two minutes and requires minimal equipment (infrared video or Frensel glasses), there is great interest in expanding and independently duplicating these findings. This concludes the five part series on acute vertigo and stroke. Next week we will take a look at recording techniques for nystagmus. References: Kattah, J., Talkad, A., Wang, D., Hsieh, Y., & Newman-Toker, D. (2009). HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke, 3504-3510 v

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- W SW 2Document192 pagesW SW 2gjuiolpNo ratings yet

- W SW 2Document192 pagesW SW 2gjuiolpNo ratings yet

- Height Increase JournalDocument63 pagesHeight Increase JournalgjuiolpNo ratings yet

- GTA CodeDocument5 pagesGTA CodegjuiolpNo ratings yet

- Jadwal TROPMED 10Document6 pagesJadwal TROPMED 10Ryan HendryNo ratings yet

- Seminar Ketahanan Pangan Sapi Perah 2Document10 pagesSeminar Ketahanan Pangan Sapi Perah 2gjuiolpNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Thesis 97Document109 pagesThesis 97shahzadanjum333100% (1)

- Transient Ischemic Attacks: Rodney W. Smith, MDDocument58 pagesTransient Ischemic Attacks: Rodney W. Smith, MDNatalija TomićNo ratings yet

- Vestibular Neuritis HandoutDocument3 pagesVestibular Neuritis HandoutPrisilia QurratuAiniNo ratings yet

- The Efficacy of Venlafaxine, Flunarizine, and Valproic Acid in The Prophylaxis of Vestibular MigraineDocument5 pagesThe Efficacy of Venlafaxine, Flunarizine, and Valproic Acid in The Prophylaxis of Vestibular MigraineagustianaNo ratings yet

- Primary Care Guidelines VertigoDocument1 pagePrimary Care Guidelines VertigoSyahidatul Kautsar NajibNo ratings yet

- Central VertigoDocument9 pagesCentral VertigoDiayanti TentiNo ratings yet

- Soap Notes 101Document45 pagesSoap Notes 101CELINE MARTJOHNSNo ratings yet

- ENT CourseDocument29 pagesENT Coursetaliya. shvetzNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical Gerontology & Geriatrics: Pradnya Dhargave, PHD, Ragupathy Sendhilkumar, MSC, MPTDocument5 pagesJournal of Clinical Gerontology & Geriatrics: Pradnya Dhargave, PHD, Ragupathy Sendhilkumar, MSC, MPTAlfianGafarNo ratings yet

- The Body MeridiansDocument61 pagesThe Body MeridiansAnonymous NKGMQv9100% (9)

- اسئلة neuroDocument30 pagesاسئلة neuroSoad RedaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Persistent Geotropic and Apogeotropic Positional Nystagmus of The Lateral Canal Benign Paroxysmal Positional VertigoDocument6 pagesAnalysis of Persistent Geotropic and Apogeotropic Positional Nystagmus of The Lateral Canal Benign Paroxysmal Positional VertigoRudolfGerNo ratings yet

- Course 3 - Trauamt UrechiiDocument13 pagesCourse 3 - Trauamt UrechiiLiviu LivaxNo ratings yet

- Dizziness and VertigoDocument27 pagesDizziness and VertigoPutriAyuWidyastutiRNo ratings yet

- MeniereDocument5 pagesMeniereMayls Sevilla CalizoNo ratings yet

- Vertiginous EpilepsyDocument5 pagesVertiginous Epilepsyzudan2013No ratings yet

- AnatoFisio VestibularDocument17 pagesAnatoFisio VestibularRocío YáñezNo ratings yet

- Article 1519801601Document4 pagesArticle 1519801601Graziela SpadariNo ratings yet

- ENT Notes CrakDocument52 pagesENT Notes CrakGrant KimNo ratings yet

- Clinical Practice Guideline - Ménière's Disease PDFDocument56 pagesClinical Practice Guideline - Ménière's Disease PDFCarol Natalia Fonseca SalgadoNo ratings yet

- Nausea and Vomiting in Adolescents and AdultsDocument30 pagesNausea and Vomiting in Adolescents and AdultsPramita Ines ParmawatiNo ratings yet

- Finals Reviewer and Activities NCM 116 LecDocument24 pagesFinals Reviewer and Activities NCM 116 LecMary CruzNo ratings yet

- Talley & O'Connor Quiz SampleDocument5 pagesTalley & O'Connor Quiz SamplefilchibuffNo ratings yet

- 2011-Visual Analog Scale To Assess Vertigo and Dizziness After Repositioning Maneuvers For Benign Paroxysmal Positional VertigoDocument7 pages2011-Visual Analog Scale To Assess Vertigo and Dizziness After Repositioning Maneuvers For Benign Paroxysmal Positional VertigoPingShun ChenNo ratings yet

- Cerebellar InfarctionDocument23 pagesCerebellar InfarctionShane LuyNo ratings yet

- Family Medicine 33: 28-Year-Old Female With Dizziness: Learning ObjectivesDocument6 pagesFamily Medicine 33: 28-Year-Old Female With Dizziness: Learning ObjectivesAndrea Kristin OrigenesNo ratings yet

- The Positive Times Newspaper - Wadsworth June 2011Document20 pagesThe Positive Times Newspaper - Wadsworth June 2011positivetimesNo ratings yet

- Neurologic Disorders - NCM 102 LecturesDocument12 pagesNeurologic Disorders - NCM 102 LecturesBernard100% (4)

- ENT AyaSalahEldeenDocument147 pagesENT AyaSalahEldeenFatma ShnewraNo ratings yet

- Otorrino ContinuumDocument220 pagesOtorrino ContinuumRafaelNo ratings yet