Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Environmental Review Tribunal Final Decision On Skydive Burnaby vs. Ministry of Environment

Uploaded by

Dave JohnsonOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Environmental Review Tribunal Final Decision On Skydive Burnaby vs. Ministry of Environment

Uploaded by

Dave JohnsonCopyright:

Available Formats

Environmental Review

Tribunal

Case Nos.: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

In the matter of appeals by Mikel Pitt and Skydive Burnaby Ltd., filed October 22, 2013

for a hearing before the Environmental Review Tribunal pursuant to s. 142.1 of the

Environmental Protection Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. E.19, as amended, with respect to

Renewable Energy Approval No. 7159-97BQAS issued by the Director, Ministry of the

Environment, on October 7, 2013 to Wainfleet Wind Energy Inc., under s. 47.5 of the

Environmental Protection Act, regarding the construction, installation, operation, use

and retiring of a Class 4 wind facility consisting of five turbines with a total name plate

capacity of 9 megawatts at a site located at 22211 Abby Road Lot 22, Concession 2,

Part 22, Township of Wainfleet, Regional Municipality of Niagara, Ontario; and

In the matter of a hearing held on January 6, 8, 10, 13,14, 17, 27, 28, 29, and February

28 , 2014 in Firefighters Memorial Community Hall, Township of Wainfleet, 31907 Park

Street, Wainfleet, Ontario, and continued by telephone conference calls on March 19,

20 and 27, and April 2, 4, 10, and 29, 2014.

Before: Dirk VanderBent, Vice-Chair

Appearances:

Eric Gillespie - Counsel for the Appellants, Mikel Pitt and Skydive

Burnaby Ltd.

Diane Tsang and - Counsel for the Director, Ministry of the Environment

Nadine Harris

Scott Stoll, - Counsel for the Approval Holder, Wainfleet Wind

Jody E. Johnson and Energy Inc.

Piper Morley

Terry Maxner - Presenter, on his own behalf

Dated this 14

th

day of May, 2014.

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

2

REASONS FOR DECISION

Background

[1] On October 7, 2013, Vic Schroter, Director, Ministry of the Environment (MOE),

issued Renewable Energy Approval No. 7159-97BQAS (the REA) to Wainfleet Wind

Energy Inc. (the Approval Holder), pursuant to s. 47.5 of the Environmental Protection

Act (EPA). The REA grants approval for the construction, installation, operation, use

and retiring of a Class 4 wind facility consisting of five wind turbines with a total name

plate capacity of 9 megawatts at a site (the Project Site) located at 22211 Abby Road

Lot 22, Concession 2, Part 22, Township of Wainfleet, Regional Municipality of Niagara,

Ontario (the Project).

[2] On October 22, 2013, Mikel Pitt and Skydive Burnaby Ltd. (Skydive),

collectively referred to as the Appellants, jointly filed a Notice of Appeal of the REA

pursuant to s. 142.1 of the EPA.

[3] A preliminary hearing was held in Wainfleet on November 20, 2013. The

Appellants requested and were granted a stay of the REA. Further background

respecting these matters is set out in the Tribunals Orders dated December 12, 2013,

March 11, 2014, and April 7, 2014.

[4] The Notice of Appeal indicates that Skydive operates a parachute skydiving

service which has been operating at its present location since 1948 and currently

provides approximately 10,000 skydives annually. Approximately 1,000 aircraft takeoffs

and landings are required to provide this service. Although the REA includes approval

of five wind turbines, and the Appellants appeal requests full revocation of the REA, it is

not disputed that the basis of their appeal is that wind turbines T4 and T5 will cause

serious harm to human health, because of the potential that airplanes or parachutists

will either collide with these wind turbines or be unable to safely manoeuver due to wind

turbulence generated by these wind turbines.

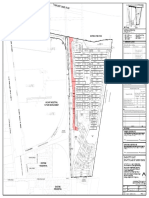

[5] Attached as Appendix A to this Decision, is a site map (Site Map) which shows

the location of wind turbines T4 and T5 (T4 and T5) in relation to the Port Colborne

Airport, which is where Skydive operates its skydiving service (the Skydive Site).

Skydive has two airplanes which transport parachutists, and the parachutist landing

area (PLA) is also located there. The map is oriented such that the top of the map is

north. Consequently, as the map shows, T4 and T5 are located west of the airport and

the PLA. The Site Map also shows a portion of Lakeshore Road which is south of the

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

3

airport. Although not shown on the Site Map, Lakeshore Road is in close proximity to

the shores of Lake Erie. T4 is the closer of the two turbines to the Skydive Site, being

1.5 kilometres (km) from the property boundary, and 1.7 km from the PLA.

[6] Pursuant to s.145.2.1 of the EPA, the onus is on the Appellants to establish that

engaging in the Project in accordance with the REA will cause serious harm to human

health (the Health Test) and/or serious and irreversible harm to plant life, animal life or

the natural environment (the Environmental Test). In this case, their appeal is in

respect of the Health Test only.

[7] In overview, the Director and the Approval Holder do not dispute that serious

harm to human health will occur if a plane or a parachutist were to collide with one of

these wind turbines, or if wind turbulence generated by the operation of T4 or T5 were

to cause a parachute to collapse. However, they assert that the probability of such

occurrence is so small, that the will cause aspect of the Health Test has not been met.

[8] Consequently, this case centres primarily on the issue of the likelihood that such

collision or parachute collapse will occur. The Approval Holder and the Director dispute

the Appellants assertion that wind turbulence generated by T4 and T5 will interfere with

the safe operation of airplanes taking off and landing at the Skydive Site. However,

they acknowledge that serious harm would result if wind turbulence prevented a plane

from taking off or landing safely. Consequently, this case focuses on causation.

[9] In their submissions, all parties agree that the Tribunal should first render a

decision on whether the Health Test has been met, and if it has been met, then allow

the parties an opportunity to make further submissions regarding which of the actions

the Tribunal may take pursuant to s.142.2.1(4), namely:

a. revoke the decision of the Director;

b. by order direct the Director to take such action as the Tribunal considers the

Director should take in accordance with this Act and the regulations; or

c. alter the decision of the Director.

[10] The parties also all agree that, although they would prefer to proceed by

submissions only, they also wish to provide additional evidence respecting remedy, as

they consider necessary.

[11] The hearing proceeded on the dates noted above, which included a visit of both

the Skydive Site, and the area within the Project site where wind turbines T4 and T5 are

located.

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

4

[12] As noted in the Tribunals Order dated April 7, 2014, the Tribunal granted an

adjournment which has the effect of excluding the period from April 5 to and including

April 9, 2014 from the calculation of time mentioned in s. 59(1) of Ontario Regulation

359/09 (which establishes the deadline for the Tribunal to dispose of the appeals). A

further adjournment was granted orally in a telephone conference call on April 10, 2014,

which also has the effect of excluding the period from April 11 to and including April 28,

2014, from this calculation of time. The net effect of these two adjournments is that the

deadline for disposition of the appeals is changed to May 15, 2014.

[13] After hearing and considering all of the evidence adduced at the hearing, and the

parties submissions, the Tribunal finds that the Appellants have not established that the

proposed location of T4 and T5 is such that they will cause serious harm to human

health. Consequently, the Appellants have not established that engaging in the Project

in accordance with the REA will cause serious harm to human health.

Relevant Legislation

[14] Environmental Protection Act

Directors powers

47.5 (1) After considering an application for the issue or renewal of a

renewable energy approval, the Director may, if in his or her opinion it is

in the public interest to do so,

(a) issue or renew a renewable energy approval; or

(b) refuse to issue or renew a renewable energy approval.

142.1(3) A person may require a hearing under subsection (2) only on

the grounds that engaging in the renewable energy project in accordance

with the renewable energy approval will cause,

(a) serious harm to human health; or

(b) serious and irreversible harm to plant life, animal life or the

natural environment.

145.2.1 (1) This section applies to a hearing required under section

142.1.

What Tribunal must consider

(2) The Tribunal shall review the decision of the Director and shall

consider only whether engaging in the renewable energy project in

accordance with the renewable energy approval will cause,

(a) serious harm to human health; or

(b) serious and irreversible harm to plant life, animal life or the

natural environment.

Onus of proof

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

5

(3) The person who required the hearing has the onus of proving that

engaging in the renewable energy project in accordance with the

renewable energy approval will cause harm referred to in clause (2) (a)

or (b).

Powers of Tribunal

(4) If the Tribunal determines that engaging in the renewable energy

project in accordance with the renewable energy approval will cause

harm referred to in clause (2) (a) or (b), the Tribunal may,

(a) revoke the decision of the Director;

(b) by order direct the Director to take such action as the Tribunal

considers the Director should take in accordance with this Act

and the regulations; or

(c) alter the decision of the Director, and, for that purpose, the

Tribunal may substitute its opinion for that of the Director. .

Same

(5) The Tribunal shall confirm the decision of the Director if the Tribunal

determines that engaging in the renewable energy project in accordance

with the renewable energy approval will not cause harm described in

clause (2) (a) or (b).

Issue

[15] The issue is whether engaging in the Project in accordance with the REA will

cause serious harm to human health.

Discussion, Analysis and Findings

Introduction

Overview

[16] Much of the evidence adduced in this proceeding is not in dispute. The

Appellants assert that engaging in the REA, specifically the physical presence of T4 and

T5, and the wind turbulence generated by them when they are operating, will cause

serious harm to human health. They assert that the harm will be caused to pilots who

operate Skydives airplanes and to skydivers. As the circumstances for airplane pilots

differ from those of skydivers, the Tribunal has structured its analysis to separately

consider the application of the Health Test to each of them. Before turning to each of

these areas, the Tribunal begins with general findings respecting the opinion evidence

adduced in this proceeding, as well as findings regarding the scope of the Health Test

as it is to be applied in this case.

[17] The Tribunal has considered all the evidence and the parties submissions in

detail. However, because this comprises a large volume of information, it is not feasible

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

6

to produce a full synopsis of the evidence and submissions within a written decision of

reasonable length. Consequently, in this Decision the Tribunal has only included a

summary of the more salient evidence and submissions provided to the Tribunal in this

proceeding.

Opinion Evidence

Witnesses who provided opinion evidence

[18] The following witnesses were qualified by the Tribunal to give opinion evidence

on behalf of the Appellants:

Mikel Pitt, Appellant, who was qualified to give opinion evidence in the areas

of parachute instruction and airplane piloting;

Joseph Chow, who was qualified to give opinion evidence in the areas of

parachuting and parachute instruction;

Ian Rosenvinge, who was qualified to give opinion evidence in the areas of

parachuting and parachute instruction;

Jim Crouch, who was qualified to give opinion evidence in the areas of

parachuting and parachute instruction;

Rick Epp, who was qualified to give opinion evidence in the area of

parachuting;

Scott Borghese, who was qualified to give opinion evidence in the areas of

parachuting and parachuting instruction; and

Bozkurt Eralp, who was qualified to give opinion evidence in the areas of

parachuting, parachute instruction and wake turbulence as it relates to

aircrafts.

[19] The following witnesses were qualified to give opinion evidence on behalf of the

Approval Holder:

Andrew Brunskill, who was qualified to give opinion evidence in the fields of

wind resource analysis, wind farm energy assessment and wind farm

modelling;

Jerry Baumchen, who was qualified to give opinion evidence in the field of

mechanical engineering, quality engineering, manufacturing of parachuting

equipment and in parachuting;

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

7

Raymond Cox, who was qualified to give opinion evidence in the area of risk

assessment in public safety, energy and transport; and

Terrance Kelly, who was qualified to give opinion evidence in the field of

aviation safety risk management, including the proactive identification of

aviation hazards and the development of mitigation strategies.

[20] In addition to their witness statements, Messrs. Baumchen, Cox, and Kelly

provided the following reports:

Mr. Baumchen conducted an analysis of wind turbulence intensity, as well as

wind speed and direction frequency distribution, the results of which are

detailed in a report dated August 29, 2013, entitled Preliminary Turbulence

Intensity and Wind Analysis at the Proposed Wainfleet Wind Project (the

Turbulence Analysis Report);

Dr. Cox conducted a risk assessment, the results of which are detailed in a

report dated December 9, 2013, entitled Risk Assessment of Interactions

between Wind Turbines and Skydive Operations (the Risk Assessment

Report); and

Mr. Kelly conducted a safety study, the results of which are detailed in a

report dated September, 2013, entitled Safety Study of the Potential Effect of

Wainfleet Wind Energy Project on Burnaby Skydiving Operations (the Safety

Study)

[21] The Director did not seek to have the Tribunal qualify any witnesses to give

opinion evidence.

Submissions and Findings Respecting the Weighing of Opinion Evidence on the

Grounds that a Witness is not Independent

[22] Each of the parties consented to all of the expert qualifications. Regarding the

Appellants expert witnesses, the Director and the Approval Holder indicated that their

consent was qualified, in that they reserved the right to challenge the independence of

these witnesses, in support of their position that the Tribunal should give their evidence

little or no weight.

[23] In respect of these witnesses, the Director and the Approval Holder maintain that:

Mr. Pitt is an appellant in this proceeding and owner/operator of Skydive. As

such, they assert that he has a personal interest in the outcome of this

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

8

proceeding as well as a financial interest in Skydive, which he maintains will

be negatively impacted if wind turbines T4 and T5 are approved. The

Approval Holder further asserts that Mr. Pitt has given inconsistent evidence

in this proceeding regarding his business income.

Mr. Chow conducts a skydive operation in Toronto and he acknowledges that

he is an advocate against wind turbines, and has spent four years from 2007

to 2010 opposing wind turbine development in the vicinity of his business

operations. Consequently, they assert that Mr. Chow is not impartial and his

opinions are not independent.

[24] The Approval Holder further maintains that:

Mr. Borghese is an employee of Skydive and, as such, the Approval Holder

asserts that he has a personal interest in the outcome of this proceeding.

Mr. Eralp works for Skydive and a large part of the fabric of his recreational

time revolves around Skydive. As such, the Approval Holder asserts that he

has a personal interest in the outcome of this proceeding.

[25] Consequently, the Director and/or the Approval Holder assert that the Tribunal

should give no weight to the opinions of these expert witnesses.

[26] In response, the Appellants submit the claims made by the Director and the

Approval Holder are unwarranted allegations with no credible foundation. In support of

this submission, the Appellants emphasize that each of their expert witnesses has

signed an Acknowledgment of Experts Duty Form stating that they will provide opinion

evidence that is fair, objective and non-partisan. The Appellants further assert that, in

signing this form, each of these witnesses also acknowledged that this duty prevails

over any obligation to a party on whose behalf they are engaged.

[27] In light of the Tribunals findings below, the Tribunal does not find it necessary to

make a determination respecting the positions advanced by the Director and the

Approval Holder. The Tribunal has proceeded on the assumption that the Appellants

expert witnesses have provided independent and impartial opinion evidence.

Therefore, the Tribunal has considered this evidence without ascribing reduced weight

to be given to the evidence of each of these witnesses on the ground that their evidence

is not independent or impartial.

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

9

Comment respecting Alleged Witness Interference

Background

[28] The following background is taken from the Directors submissions, which the

Tribunal finds is an accurate summary.

1. On December 18, 2013, the Instrument Holder raised concerns about

interference with one of its witnesses, Rob Warner, when e-mails came to

light in which Mr. MacNeill, the Chair of the Technical and Safety Committee

(the Committee) of the Canadian Sport Parachuting Association, first

threatens to remove Mr. Warner from the Committee and the rigger

instructors list (the List) if he testifies at this proceeding and then proceeds

to suspend him from the Committee and List.

2. At the request of the Approval Holder, the Tribunal issued a summons to

Mr. MacNeill.

3. Mr. MacNeill appeared before the Tribunal on January 28, 2014 and

testified that: he was the author of the e-mail exchange with Mr. Warner

between December 15

th

and December 17, 2013 in which he asked Mr.

Warner to bow out of appearing as a witness at this hearing; told Mr.

Warner that if he does not do so, he will drop him from the Committee and

the instructors list; and ultimately suspended Mr. Warner from the

Committee and List.

4. Mr. MacNeill testified that he learned about Mr. Warners involvement in this

hearing from Debbie Flanagan, President of the Association, and stated that

he did not know the origin of Ms. Flanagans information.

5. The Board of Directors gave Mr. MacNeill the option to fire Mr. Warner from

the Committee or suspend him and he decided to suspend him. Mr.

MacNeill is not part of the Board of Directors and was not involved in the

Boards decision-making process.

6. Mr. Warner was removed from the List because Mr. MacNeill as Chair of the

Committee has a requirement that, to be on the List, a person must also be

on the Committee.

7. At the time Mr. MacNeill sent the emails, he did not appreciate fully what

might come about because of them.

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

10

Submissions

[29] The Director made the following submissions:

1. The Tribunal should note that the emails provided by Mr. MacNeill include

an e-mail from Ms. Flanagan stating that this issue was time sensitive as

the Pitts are working with their lawyer on their defence. It is thus

reasonable to infer that Ms. Flanagans information came from the Pitts or

somebody associated with the Pitts.

2. Mr. Warner was proposed as a witness in this proceeding. Mr. MacNeill and

the Canadian Sport Parachuting Association attempted to dissuade him

from testifying, threatened to suspend him and then proceeded to suspend

him. These actions fall squarely within the list of actions often referred to as

contempt out of the presence of the court (i.e. contemptuous act which is

committed outside the court and by extension a tribunal).

3. Mr. McNeill and the Canadian Sport Parachuting Association might not have

intended to hinder or undermine the Tribunal process, but their actions did

so and as a result they undermined the administration of justice in the public

interest.

4. The Tribunal does not have the power to cite Mr. MacNeill and the

Canadian Sport Parachuting Association for contempt nor is it necessary to

do so in this case. The Tribunal should however include in its decision

strong wording condemning the actions taken by Mr. MacNeill and the

Association while a legal proceeding was underway because of the impact

those actions could have on the integrity of the Tribunal process.

[30] The Approval Holder endorses the Directors request. The Appellants written

submissions do not specifically respond to this request. However their submissions

include the following:

1. Mr. Warner had been suspended, pending the outcome of these

proceedings, from the Technical and Safety Committee for the Canadian

Sport Parachuting Association for representing himself as a member, to

obtain a benefit, without approval from the Associations Board of Directors.

2. Mr. Warner remains fully licenced. If he were an unbiased and independent

expert, the loss of his committee membership with the Canadian Sport

Parachuting Association would not have affected his testimony.

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

11

Findings

[31] Mr. MacNeills evidence certainly gives rise to a serious concern that the actions

of the Canadian Sport Parachuting Association influenced Mr. Warner not to testify in

this proceeding. However, the Tribunal notes that none of the parties sought to

summons Mr. Warner to give evidence in this proceeding, so the Tribunal does not have

the benefit of his evidence as to the extent of any influence or pressure placed on him,

which may have discouraged him from testifying in this proceeding. Furthermore,

Mr. MacNeill testified that he could not comment on the views of the Board of Directors

of the Canadian Sport Parachuting Association as he is not a member of the Board, and

is not invited to attend Board meetings. In such circumstances, the Tribunal is reticent

to fully censure the Canadian Sport Parachuting Association in the manner requested

by the Director, assuming that the Tribunal has the jurisdiction to condemn the

Associations actions, as has been requested by the Director. Nevertheless, the

Tribunal finds that it is fair to observe, that given its role as a non-legislated organization

which regulates sport skydiving activities in Canada, the Association has a responsibility

to conduct its affairs in an orderly and transparent manner that is fair to both its

members and the public. The Association certainly could have provided a more

comprehensive response to what are very serious allegations, and, in the Tribunals

view, its public reputation suffers for it not having done so.

Whether engaging in the Project in accordance with the REA will cause serious

harm to human health

[32] The Tribunal has divided its analysis and findings under three subject areas:

(i) the nature and extent of the wind turbulence generated by wind turbines T4 and T5;

(ii) harm to airplane pilots; and (iii) harm to skydivers. Although the Tribunal has also

organized the parties submissions under these subject areas, the Tribunal confirms that

it has considered the submissions in their entirety when make findings respecting each

of these subject areas.

Wind Turbulence

Introduction

[33] The Tribunal finds that it is not disputed that a wind turbine generates turbulence

in the air both immediately in front of the wind turbine blades, and for some distance

behind these blades. This turbulence has two components:

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

12

Blade tip vortices due to air counteracting the wind turbine blade torque, and

in part due to aerodynamic effects due to the finite extension of the blades;

and

Reduction in ambient wind speed as the wind turbine blades extract power

from the wind.

[34] In lay terms the vortices can be described as rotational or spinning pockets of air.

These vortices will mix with downstream air flow.

[35] The purpose of this section of the Tribunals Decision is to first address the

parties dispute as to the predicted extent of the turbulence that will be generated by

wind turbines T4 and T5. The Tribunals findings in this regard, will then be considered

elsewhere in this Decision when the Tribunal addresses how this turbulence will affect

airplanes and skydivers.

[36] The Tribunal notes that the Director did not call any witnesses to testify

respecting wind turbulence.

Evidence Adduced by the Appellants

Mr. Eralp

[37] Mr. Eralp is a commercial pilot, holds a degree in mechanical engineering, and

wrote an engineering thesis on Bluff body vortex shedding which refers to turbulent

wake behind a wing. Mr. Eralp states that a wing includes a wind turbine blade.

Mr. Eralp also explains that:

Modern parachutes are very effective non-rigid wings, designed such

that the weight of the suspended parachutist leads to sustained inflation

of an envelope of material shaped in section and span substantially, like

any aircraft wing, that can be glided and guided to a safe landing area.

The performance of these wings allows for a range of speeds, in large

part to allow for the landing noted.

[38] Mr. Eralp expresses his view that analytical models used to predict turbulence

are limited to a mere statistical evaluation, even with the benefit of well-defined

constraints. He describes atmospheric turbulence as a rapid change in intensity and

direction of air flow experienced by a body (or wing) subjected to its aerodynamic

effects. He expresses his view that modern computers have yet to solve for

turbulence analytically, though many models are used to approximate. He also

maintains that, as industrial wind turbine projects are sited with the expectation of a

successful wind field for exploitation, there is clearly such a field, which means that

there will be significant wake turbulence, models notwithstanding. In cross-

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

13

examination he stated that he defines the term significant as enough to affect

operations, for example, like a drop zone.

[39] Mr. Eralp relies on an article he obtained by internet search entitled Wind

Turbines Wake Turbulence and Separation (the Turbulence Article), which provides a

summary opinion of the author Ralph Holland, which is based on research of others

whom Mr. Holland has cited as references in this article. Mr. Holland uses data for the

wind turbines he was considering and states his conclusion in the summary section of

this article:

Wake turbulence behind a single wind turbine can extend beyond 16

blade diameters, being composed of both blade-tip vortices and the

reduction of wind speed due to power extraction. It takes time for the

airstream to become laminar, and further time for it to recover to the

original airstream velocity.

There is a tendency for the downstream to rotate at the blade rate and it

has been shown that this rotation moves downstream to extents that are

not insignificant. The near-field turbulence is coupled with a significant

down-stream reduction in wind velocity, which represents wind shear,

that is dangerous to flight. The wind velocity decreases to 2/3 of the

free-stream velocity just in front of the turbine and is further reduced to

1/3 of the free-stream flow behind the turbine when the turbine is

operating at maximum power extraction.

[40] Mr. Eralp states that the length of the turbulence wake has been seen and

measured at 10-16 times the diameter of the blades, and he asserts that it has been

posited to go well beyond by some researchers. As described below, Mr. Brunskill, an

expert witness who testified on behalf of the Approval Holder, has conducted a

turbulence intensity assessment for wind turbines T4 and T5. Mr. Eralp notes that this

assessment predicts that turbulence generated by these turbines will only increase free

stream turbulence by 1% on Skydive property. He states that this strikes me as

unlikely. Mr. Eralp also considers that the horizontal expansion of the turbulence wake

is wider than that described by Mr. Brunskill in his assessment. Mr. Eralp expressed his

opinion that a conservative estimate of this spread is 10 to 15%.

[41] In cross-examination, Mr. Eralp admitted that he did not model the turbulence

intensity himself. He acknowledges that he does not know the type of wind turbine

referenced in the Turbulence Article, other than the model number which indicates that

it has two blades, not three.

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

14

Mr. Chow

[42] Mr. Chow has 40 years experience in drop-zone operations and has skydived

11,000 times. He is a pilot and skydiving instructor and instruction ratings coach. His

evidence in his witness statement respecting turbulence states:

Turbulence, a deadly killer: Studies of wind turbines both off-shore and

on-shore in Europe have confirmed that the downwind effects of wind

turbines can be diagnosed for over 15 miles. Needless to say, these

huge structures will create unwanted turbulence that will affect the safety

of both landing parachutists and airplanes at the Skydive Burnaby site.

Evidence Adduced by the Approval Holder

Mr. Brunskill

[43] Mr. Brunskill is a mechanical engineer and a consultant employed by GL Garrard

Hassan Canada Inc. (GL), who was retained by the Approval Holder, through its

solicitor, to conduct an analysis of wind turbulence intensity, as well as wind speed and

direction frequency distribution. The results of this assessment are summarized in the

Turbulence Analysis Report. Mr. Brunskill states that he co-wrote this report, performed

technical and quality checking and co-approved this report. This report confirms that

WindFarmer software has been employed, using an industry standard model, to

estimate turbulence intensity. It also confirms that GL has validated the specific model

used, which assumes that the wake will spread equally in the horizontal and vertical

directions. This report also notes that: (i) the wake width at any downwind position is a

function of the distance downwind, the turbines thrust co-efficient and the ambient

turbulence intensity; and (ii) GL has used site specific predicted values when modeling

turbine wakes at the Wainfleet site.

[44] Mr. Brunskill stated the purpose of the study was to assess the increased level of

mean turbulence intensity, rather than trying to predict the length of the turbine wake.

He explained that very tiny effects can travel a great distance, and, therefore, it is more

appropriate to estimate magnitudes of any wake rather than specify a length of the

wake. He further stated that the level of increased turbulence intensity at any point in

the wake of a wind turbine will be site specific and depends on several factors including:

the distance of the point of interest from the wind farm,

the height of the point of interest,

the number of turbines inducing the wake,

the turbine locations,

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

15

the thrust co-efficient of the specific turbine model, and

the ambient turbulence intensity.

[45] Mr. Brunskill states that wind turbines induce turbulence through several

mechanisms including:

boundary layers which form on the rotor blades,

vortices shed by the blades,

flow separation from the wind turbines nacelle and tower, and

mean velocity shear of the wake.

[46] Mr. Brunskill notes that it does not appear that Mr. Eralp has carried out an

analysis or modelling to evaluate expected wake induced turbulence levels at the

Skydive site. He further expresses his view that it is not clear why Mr. Eralp implies that

a statistical evaluation of turbulence is insufficient for use in these circumstances, or

what alternate type of evaluation Mr. Eralp would suggest.

[47] Mr. Brunskill states that turbulence intensity decreases with distance from the

wind turbine. He notes that the modelling analysis conducted confirms that the

horizontal spread of the wake is at most a few degrees wider than the diameter of the

wind turbine, much less than Mr. Eralps estimate that the spread is in the range of 10 to

15%.

[48] Mr. Brunskill describes the near wake region as the distance up to five rotor

diameters from the wind turbine, which in this case is up to 500 metres (m). He states

that, in this region, the turbulence intensity is the highest. He describes the far wake

region as the distance beyond 500 m, where he states that the magnitude of wind

turbine wake effects, such as increased mean turbulence intensity and reduced mean

wind speed, decay with downwind distance. He testified that these wake effects will

gradually become marginal or undetectable by standard wind measurement technology.

[49] The Turbulence Analysis Report provides data on the predicted change in

turbulence over distance, calculated for several ambient wind speeds. The results are

shown in Figures 3 to 7 of the Report, each of which is a graph showing predicted

turbulence generated by the wind turbine against the ambient turbulence predicted for

each wind speed in the absence of the wind turbine. The Report indicates that the data

represents average turbulence intensity statistics presented at the hub height of the

wind turbines.

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

16

[50] As this information is more readily comprehensible in graph form, Figure 3 is

attached to this Decision as Appendix B, as an example. Figure 3, which is based on

an ambient wind speed of 3 metres per second (m/s) indicates that: (i) there will be

increased turbulence intensity as compared to ambient turbulence levels; and (ii) this

increase varies from 6% in the range up to approximately 400 m from the turbine, to

less than 1% at approximately 1,200 m from the turbine, and then decreases very

slightly at the Skydive Site property line, which is 1,500 m from the turbine, and within

this Site area. The other graphs for ambient wind speeds of 5, 7, 9, and 11 m/s, show

similar patterns, although the distance at which the difference in turbulence intensity is

less than 1% becomes shorter (e.g. for wind speed of 11 m/s, this distance is

approximately 700 m from the wind turbine). Mr. Brunskill characterized the 1%

increase as a level that is very difficult and maybe impossible to detect with standard

measurement equipment.

[51] Mr. Brunskill testified that ambient turbulence intensity is the most important input

to the model. He notes that ambient conditions vary from project to project, and they

can also vary for the same project at different times. He also testified that ambient

turbulence is the most important factor in how far a wake will extend, noting that higher

levels of turbulence in the atmosphere will result in a wake that is shorter as compared

to the wake generated in lower levels of turbulence. Stated another way, he indicates

that there will be a longer wake in stable conditions than in unstable atmospheric

conditions.

Submissions made by the Appellants

[52] The Appellants make the following submissions:

Mr. Brunskill admitted that one of the main purposes of the WindFarmer

software modelling is to help minimize the decrease in turbine efficiency and

physical damage as a result of wake effects from other turbines, as wake

turbulence from wind turbines can adversely affect other wind turbines in their

wake.

The study predicted that, regardless of wind speed, the changes in turbulence

intensity either in the ambient condition and/or as result of the spinning blades

of the proposed wind turbines would be essentially insignificant across most

of the areas leading to, and including, all of the Skydive airfield. In essence,

there would be no variation in either ambient or wind turbine turbulence at

ground level and no changes in turbulence at higher wind speeds.

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

17

A model that fails to demonstrate the influence of ground structures and wind

speed on turbulence intensity can be of no relevance to the question of

whether the wake turbulence of wind turbines will cause serious harm to

human health, in this case to parachutists. Both ground structures and wind

speed are well known sources of great turbulence which pose life threatening

hazards to all skydivers. The WindFarmer model provides no information

regarding either and is, therefore, of no value to this hearing.

In his evidence, Mr. Kelly affirmed that the effects of wind turbines on aviation

and in particular skydiving operations have not been fully studied.

Consequently, there is little information on air turbulence downstream of

turbine blades, and that which exists is sometimes contradictory.

Submissions made by the Approval Holder

[53] The Approval Holder makes the following submission:

Mr. Brunskill was the only witness qualified to provide expert opinion evidence

on turbulence from wind turbines; his was the only evidence of turbulence that

pertained to the Project, was detailed and provided a clear path for his

conclusions. His evidence regarding turbulence should be preferred to that of

the Appellants' witnesses.

Submissions made by the Director

[54] The Director makes the following submission:

Mr. Brunskill remained within his area of expertise and provided a detailed

pathway for his conclusions including data, assumptions and analyses. As a

result, his evidence and opinions should be given considerable weight by the

Tribunal.

Findings on Turbulence generated by Wind Turbines T4 and T5

[55] The Tribunal observes that there is little disagreement in the evidence of

Mr. Eralp and Mr. Brunskill. They both agree that wind turbulence will be generated by

wind turbines T4 and T5. The Tribunal finds that Mr. Eralps evidence can be fairly

characterized as being more general in nature, as compared to the evidence provided

by Mr. Brunskill, as Mr. Eralp does not provide a site specific analysis. Instead he relies

on an article that relates to another project proposal. The Appellants did not dispute

Mr. Brunskills evidence that turbulence analysis must be site specific, both in terms of

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

18

the specifications of the wind turbine model and location, and site specific ambient

environmental conditions. However, Mr. Eralps evidence is not inconsistent with the

more detailed analysis provided by Mr. Brunskill. Both agree that turbulence will be

generated and its intensity will decrease with distance from the wind turbines.

[56] The Appellants assert that the model used by Mr. Brunskill, in essence, provides

that there will be no variation in either ambient or wind turbine turbulence at ground

level and no changes in turbulence at higher wind speeds. They maintain, therefore,

that the model fails to demonstrate the influence of ground structures and wind speed

on turbulence intensity. The Tribunal does not accept this submission. The intent of

Mr. Brunskills analysis is to predict the increase in average turbulence intensity levels

caused by the wind turbines, as compared to average turbulence intensity predicted for

the various ambient wind speeds. Mr. Eralp acknowledges that many computer

software models are used to approximate turbulence. To the extent that increased

turbulence intensity is created by wind flowing over ground structures at ambient wind

speeds, it is Mr. Brunskills uncontradicted evidence that higher levels of atmospheric

turbulence will shorten the length of the turbulence wake generated by the wind

turbines. Consequently, the Tribunal does not accept the Appellants assertion that the

WindFarmer model is of no value to this hearing.

[57] Regarding the evidence of Mr. Chow, the Tribunal finds that his opinions are only

conclusory in nature. He refers to studies conducted in Europe, but does not provide

any reference or discussion of these studies. Even if the Tribunal accepts his assertion

that these studies show that downwind turbulence extends for over 15 miles, he does

not provide any analysis of the change, if any, in turbulence intensity over this distance,

nor does he address whether these European studies are based on projects whose

profiles are similar to the Project in this case. Consequently, the Tribunal does not find

that he has provided sufficient analysis to support his conclusions that turbulence is a

deadly killer, and that engaging in the Project in accordance with the REA will generate

turbulence that will affect the safety of both landing parachutists and airplanes at the

Skydive Burnaby site.

[58] The Tribunal notes Mr. Kellys observation that the effects of wind turbines on

aviation and in particular skydiving operations have not been fully studied, and,

consequently, there is little information on air turbulence downstream of turbine blades,

and that which exists is sometimes contradictory. However, the Health Test is

predictive in nature in that the Tribunal must determine if an event (serious harm to

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

19

human health) will occur if the Project proceeds. Therefore, the Tribunal must proceed

on the best evidence available.

[59] In light of the above findings, the Tribunal concludes that the analysis provided in

the Turbulence Analysis Report provides a reasonable prediction of the percentage

increase in turbulence intensity caused by wind turbines T4 and T5.

Harm to Skydives Airplane Pilots

Background

[60] The following evidence is not in dispute.

[61] Skydives operations are located at the Port Colborne airfield, which is a

registered aerodrome under Canadian Air Regulations, which are passed pursuant to

the federal Aeronautics Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. A-2. Under the Aeronautics Act, certified

airports are subject to Airport Zoning Regulations, which regulate the use of lands

adjacent to or in the vicinity of a Transport Canada airport or airport site. The Port

Colborne airfield is not a certified airport, and, therefore, there are no Airport Zoning

Regulations.

[62] The Canadian Air Regulations require that pilots taking off or landing at an

aerodrome fly their airplanes following Visual Flight Rules (also referred to as VFR),

which means that pilots are required to visually identify objects in their flight space in

order to safely navigate their planes. More specifically, pilots are required to maintain

their own separation from each other and from obstacles, remain clear of clouds, fly

when they have a minimum flight visibility of three miles, and fly at a minimum of 500

feet (ft) vertically and/or 500 ft laterally spaced around all obstacles.

[63] The Canadian Air Regulations also require that pilots adopt a standard circuit

pattern to approach and land on a runway which is described as rectangular box

landing pattern. The particulars regarding the current flight pattern at Skydive are

described by Mr. Pitt in the Appellants evidence below.

[64] Skydive has two single engine airplanes which it uses to transport skydivers.

Skydive conducts approximately 1,000 aircraft take-offs and landings each year. The

proposed locations for wind turbines T4 and T5 are 1.5 km from the property boundary

of the Port Colborne aerodrome and 1.7 km from the location on the aerodrome

property which is the target area for a skydivers final touch down when landing.

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

20

Evidence Adduced by the Appellants

Mr. Pitt

[65] Mr. Pitt is a licenced pilot. In his witness statement, he provide an aerial map on

which he super-imposed a coloured diagram showing the legs of box pattern and the

typical direction of the parachutist jump run area, a copy of which is attached to this

Decision as Appendix C (the Flight Pattern Diagram). As the colours will not be

reproduced in a black and white copy, the Tribunal has added numbers to the diagram

and legend. In his oral testimony, Mr. Pitt referred to this Diagram when describing the

rectangular box flight pattern currently used by Skydive. He states:

So you fly off, we turn at 500 feet, 90 degrees, because we don't want

to be flying off into the water, if we lose an engine, then we're swimming.

So we turn 500 feet, which is a safe altitude for 90 degrees, climb up

from 5,800 feet. Now we turn. We're going to say it's our "downwind,"

that's the red line. We call it downwind, that's what we do on our

downwind for landing, but as we're climbing out, and that is

approximately one mile past the airport. And we climb out from there

and climb up to a 1,000 feet. We're all safe, 1,500 feet, we now take off

our seatbelts and continue our climb up.

Q. Where do you do your climb up?

A. Upwind of the airport.

[66] Mr. Pitt testified that Skydives current landing circuit, along the downwind leg

(shown as Number 3, the red line on the Flight Pattern diagram) would place an

airplane within 300 ft of T4 or T5. He states that this is not safe, and is in direct conflict

with Transport Canada Safety Regulations. In this regard, he refers to s. 602.14 of the

Canadian Air Regulations which provides that, except when flying over a built-up area

or an open-air assembly, the airplane is required to maintain a distance of at least 500 ft

from any persons, vessel, vehicle or structure.

[67] Mr. Pitt also stated his opinion that erection of wind turbines 1.7 km from the

landing strip would immediately impact the landing pattern. He stated that, under

present circumstances, regardless of where a parachutist is in the flight pattern, in the

event of an emergency, he, as the pilot, would be able to proceed directly to the airport

and attempt to land the plane. He expressed his view that this will no longer be the

case if the wind turbines are erected, as, depending on the situation, he would be forced

to determine some other, considerably less safe place to attempt a landing.

[68] Mr. Pitt observes that Transport Canada, in a letter sent to him dated January 26,

2011, stated that the proposed wind turbines may adversely affect Skydives operations

and aircraft operating the circuit at the Port Colborne airfield. Mr. Pitt expressed his

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

21

opinion that safe and efficient use of an aerodrome can be seriously eroded by the

presence of obstacles within or close to the take-off or approach areas. In support of

this observation he provided an excerpt from s. 4 of the Aeronautical Information

Manual which speaks to obstacle restrictions.

[69] In cross-examination, Mr. Pitt explained that, when flying the box pattern, the

plane flies each leg to achieve the required altitudes before turning to the next leg,

noting that climb rates can vary based on factors such humidity and the temperature of

the day. He further explained that the actual ground level distance the plane travels to

achieve these altitudes varies depending on the rate of the planes ascent/descent and

ambient wind speed conditions. He alternatively described this as the air speed

remaining the same, but the ground speed varying. He stated that the

upward/downward leg, as shown on the Flight Pattern diagram, is approximately one

mile (1.6 km) from the aerodrome, which he described as their safe practice. However,

he also explained that this pattern would be adjusted if skydivers were in this area on

their return path descending to the landing area.

[70] When asked, in terms of this basic flight procedure, what, if anything, would be

different if those turbines are erected as proposed, Mr. Pitt stated:

Well, that would just that would put us approximately 5 to 600 feet

above the turbines right there, it doesn't give you a lot of room for error.

And we need to be at least a mile out, because [of] the glide angle of the

airplane. We can't be right over on top of the airport if the engine quits.

We need to be sort of upwind of the airport to glide back, and having

500-foot -- sorry, 475-foot spinning blades up there is going to be

turbulent and, you know, possible collision hazard.

[71] In his oral evidence Mr. Pitt testified regarding the concern relating to an engine

failure. He explained:

That's why we fly that pattern, because if there is a problem with the

plane, we can always get back to the airport at those altitudes. Which,

from a thousand feet to the ground, it's -- you know, that's the area of

sketchiness. Once you're above a thousand feet, you can glide places

and things like that. That's why we want to maintain, put a mile under

the drop zone, that you do have an engine out, you can go there.

We come off the ground, you know, come up, we turn right at 500 feet,

then we turn right again to go to the downwind. At any one of those

points when you make that first turn, now we are looking for alternates,

because we're not going to make the airport if the engine quits now.

We need to, you know, 500 feet if we're straight off, we're going straight

off. When we turn to that right out, now we have fields there that we

might be able to land into where the turbines are, there are other fields

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

22

that we can make. Once we get to that thousand foot mark, we can

probably make the airport at that point. But there's a critical point, again,

from the time you leave the ground to get to a thousand feet.

Mr. Eralp

[72] Mr. Eralp testified that any wing needs a minimum speed to fly, and passengers

of aircraft in turbulence are subjected to chaotic bouncing as the wings generate varying

levels of lift associated with the changing localized speed of air moving over the lifting

surfaces, as well as responding to up and down drafts in the 3 dimensional turbulent

field. He indicates that the degree of discomfort can be compared to the percentage of

wing speed loss. He uses, as an example, a jetliner configured for approaching an

airport at 160 knots suddenly flying at only 125 knots. He states that even this 20%

reduction would result in very severe wind shear and justify aborting a landing. He

further states that much more than this range of speed loss becomes increasingly

unrecoverable, which occasionally closes airports to traffic. But a 5 knot loss would be

noted by a flight crew as minimal, and corrected.

[73] In comparing turbulence produced by aircraft to turbulence generated by a wind

turbine, Mr. Eralp testified:

Despite the fact that I've read in one of the reply statements, that wings,

turbines, etcetera, are different. I deny that. The wind tip vortex which is

generated by the difference of pressure below and above, and those are

loose terms, of the wing. And they look roughly the same on all wings,

granted that an elliptical formed at the end, a square end, other shapes

at the end change them. But they all have basically the same tip vortex.

Secondarily, in generating lift, which is what the turbines use to convert

wind energy to motion energy and then electrical energy, that has

consequence vortex; that is what I studied at the university.

The tip vortex I'm used to, every day in flight. The vortex generated as a

part of lift is specifically what I studied. So my consistent experience of

it, is equal to the task of speaking to wind turbulence. I think that if I flew

a large aircraft through the wake of a wind turbine, I would pay for it.

That's pilot speak for, I would die and I would kill 200 passengers. We're

not to be immoderate, we're paid to be somewhat task-termed. But I

can't hide from the fact, I just wouldn't do it.

[74] Mr. Eralp also testified that it would be highly unlikely that a plane would fly within

the near wake of a wind turbine.

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

23

Evidence Adduced by the Approval Holder

Mr. Kelly

[75] Mr. Kelly is a licenced pilot, a regulatory inspector, aviation accident inspector,

safety analyst, safety evaluator, and safety policy advisor. He conducted a safety study

and prepared the 2013 Safety Study.

a. Potential risks to aircraft: Collision with turbine

Loss of control while maneuvering to

avoid a turbine

Licensed pilots are responsible for (and commercially-licensed pilots are

experienced in) avoiding obstacles when operating under visual flight

rules (VFR). In the future pilots operating out of the aerodrome at Port

Colborne would be aware of the location of the turbines because of the

regulation required mitigation imposed on the wind turbine owner.

Specifically, the turbines will be:

known obstacles due to the requirement to publish their location

in NOTAMS (notice-to-airmen),which are read by all aviators;

physically lighted in accordance with Transport Canada (TC)

standards;

marked on local and regional aviation maps; and

highlighted in the Canada Flight Supplement (CFS).

[The CFS is a flight planning document that contains operating

information on all registered and certified aerodromes in Canada. In

addition to providing information on runways, operational procedures,

minimum altitudes, and communications, it cautions pilots on known

hazards in the vicinity of an aerodrome hazards such as the location

and height of communication towers, wildlife activity, areas where wind

shear is prevalent, and parachuting activity.]

Furthermore, the minimum visibility requirement for skydiving (5 statute

miles) is considerably more than TC visibility requirements for VFR pilots

(3 statute miles). Therefore, pilots carrying skydivers will be better able

to identify and avoid the lighted obstacles. Furthermore, visiting pilots

will continue to need prior permission to land or operate from the

aerodrome, and will likely be briefed before arriving or departing the Port

Colborne aerodrome on the presence and location of the turbines.

Nevertheless, there would be a potential risk of collision with a turbine, or

a loss of control while maneuvering to avoid the obstacle if a pilot

experienced an airborne emergency that required an immediate forced-

landing. Examples of such emergencies include an engine failure in the

climb, or an engine or cabin fire.

Assessment of risk to skydiving aircraft

The operational safety analysts determined that the risk of colliding with

one of the two turbines, or losing control of the aircraft while avoiding a

turbine during an emergency would be rare. They made this

determination because:

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

24

The relatively short runway length and the high aircraft operating

weights will require pilots to take-off into wind on runway 21 on a

heading that takes them away from the turbines;

The subsequent right-hand cross-wind turn will enable pilots to

climb on a track that avoids overflying the turbines while they

continue the climb to an altitude well above the turbines;

Once established in a climbing pattern, they will be able to see

the two turbines well below them, and in the event of an

emergency, find an acceptable field or landing area on which to

force land, clear of either of the two turbines, which are

separated by almost one-half a kilometer.

It was determined that if there were residual risks, they could be

mitigated by developing and adhering to local procedures that ensure

pilots remain vertically and laterally clear of the turbines after takeoff and

during descent for landing.

[76] In his witness statement Mr. Kelly states:

It is my opinion that pilots will seldom be exposed to air turbulence

generated by T4 and T5, and that the risk of a loss of aircraft control can

be effectively mitigated because:

(a) the prevailing winds are such that air turbulence will most often

exist in areas where aircraft will not operate;

(b) winds that potentially could cause turbulence in the low level

airspace near the runway (i.e., winds from 260 to 280) occur

only 12% of the time, and on average at speeds that would

generate minimal turbulence near the runway. Furthermore,

these westerly winds almost always occur during the months of

January and April, when there are few (April) or no (January)

skydiving aircraft operating at Port Colborne;

(c) terrain and buildings between the turbines and the runway will

deflect or dissipate turbulence, and pilots frequently deal with

turbulent air when landing aircraft; and

(d) turbulent air indicators could be positioned near the runway to

warn pilots who are approaching to land.

[77] In his response witness statement Mr. Kelly states:

The lateral and longitudinal dimensions of traffic patterns are not rigid,

and differ from aerodrome to aerodrome, and even at a single

aerodrome - depending on wind conditions, topography and the types

and number of aircraft flying in the circuit. Therefore, the VFR traffic

circuit should not be understood to be a rigid line over precise landmarks

that would require pilots to fly in the immediate vicinity of the turbines. In

fact, there are other safety regulations that require pilots to vertically and

laterally avoid obstacles. Consequently, the future traffic pattern at the

Port Colborne aerodrome would have longitudinal and lateral dimensions

that would keep pilots clear of the turbines.

Aircraft taking-off and leaving the traffic pattern as almost all aircraft

will do at Port Colborne will normally climb on runway heading to a

height of at least 500' above ground (or higher if the pilots choose)

before commencing a climbing turn of approximately 90 degrees to the

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

25

north. Pilots will climb on this track which provides considerable

horizontal clearance from the turbines until they exceed the circuit

altitude (see the paragraph below). They then will be free to maneuver

the aircraft as they continue to climb through altitudes that will provide

considerable vertical separation from the two turbines.

Furthermore, the circuit pattern is three dimensional (i.e., it contains an

"altitude component"). Consequently, a jump aircraft climbs out after

take-off, and as it climbs above circuit altitude (usually 1000 feet above

ground level), the pilot "leaves" the traffic circuit. As the aircraft climbs

above the circuit height, the pilot is no longer expected/required to fly the

rectangular pattern.

The pilot of the jump aircraft will not normally have reason to fly a

complete rectangular pattern at the circuit altitude, and therefore will not

be in proximity to any turbine. Furthermore, the regulations require a

pilot to operate an aircraft at a safe distance from any obstacle, including

a turbine, so when a pilot is in the circuit, the regulations will require the

pilot to fly the aircraft to avoid the obstacle. Future traffic patterns will

take this into account, just as they do in many locations where there are

topographically-based obstacles that influence the dimensions of the

traffic pattern. In the future, this information will be included in the

Canada Flight Supplement (CFS), published by NAV CANADA, and in

numerous other sources that exist to inform local and transient pilots of

the unique circumstances that are found at almost all aerodromes, small

and large.

The future presence of the turbines shall not contravene aviation

safety regulations and standards.

[78] Mr. Kelly testified that Transport Canada requirements are that pilots fly a

minimum of 500 ft away from structures and the proposed turbines placement would

allow aircrafts flying the existing circuit at Port Colborne aerodrome to be in compliance

with that requirement.

[79] Regarding Mr. Eralps evidence regarding turbulence, Mr. Kelly states in his

response witness statement:

The information regarding air turbulence presented by the witness is

confused. The comparisons of wakes generated by boats, aircraft and

wind-turbines are conflated, as is the comparison of turbulence

generated by wind turbines with the severe updraft and downdrafts within

and in the vicinity of thunderstorms (cumulonimbus clouds). To illustrate:

the characteristics of wing vortices and wake turbulence generated by

large aircraft in landing or take-off configurations significantly differ from

turbulent air generated by wind turbines in the way they are formed,

their dimensions, the subsequent directions of travel, and how they are

dispersed. Wakes from large aircraft configured for landing or take-off

are strongest and prevail the longest in low wind conditions; while we are

informed that turbulent air generated by wind turbines is strongest in high

wind conditions. Stated another way: strong winds disperse and break-

up aircraft-generated vortices, but perpetuate wind turbine generated

turbulence. Consequently, the comparison to different forms of air

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

26

turbulence and wakes especially by juxtapositioned analogies is

misleading and often incorrect.

[80] Dr. Cox is a mechanical engineer with expertise in industrial safety and risk

assessment. In response to Mr. Eralps evidence reference to a jet liner as an example,

Dr. Cox states:

There is no comparison with the wind turbines. In the case of a typical

heavy aircraft such as an airliner, the power generated by the engines in

propelling the airplane is ultimately absorbed in the turbulent disturbance

it creates in the atmosphere as it passes. That disturbance is largely

created by the lifting surfaces (i.e., wings) and takes the form of vortices

in the air. In the case of a wind turbine, similar phenomena are at work

but overall energy is extracted from the atmosphere. That is one reason

why the hazard of wind turbine wakes cannot be compared with that of

airliner wakes. The second reason is that the power levels are of a

totally different order: a typical large airliner injects into the atmosphere

the equivalent of 50,000 to 100,000 horsepower, while a single wind

turbine of the type proposed for Wainfleet absorbs from the atmosphere

about 3000 horsepower. There is no comparison.

Submissions of the Appellants regarding Harm to Airplane Pilots

[81] The Appellants rely on evidence adduced by their expert witnesses regarding

collision risks and the risks associated with turbulence. The Appellants maintain that it

is the collective view of the Appellants witnesses that the proposed wind turbines pose

a very real and serious threat to pilots and parachutists. According to the opinion of

Mr. Pitt, it is not a question of whether serious harm will occur, but when it will occur.

The Appellants submit that this appeal is not based on hypotheticals but, instead, what

will undoubtedly occur if the Project proceeds.

[82] In response to the evidence adduced by Mr. Kelly, the Appellants also make the

following submissions:

1. Mr. Kelly is an expert in aviation safety-risk management, not in skydiving or

piloting.

2. Based on the SMS Report, Mr. Kelly opined that the safety risks of the wind

turbines will be mitigated provided pilots operate their aircraft in accordance

with Transport Canada Regulations and Standards, and supplementary

procedures for skydiving operations are instituted.

3. In his erroneous opinion, pilots will not collide with the turbines if, among

other things, Skydive institutes procedures so that pilots remain vertically

and laterally clear of the turbines, even in an emergency.

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

27

4. In his erroneous opinion, pilots will also seldom be exposed to wake

turbulence generated by wind turbines because the winds that could

potentially cause turbulence, westerly winds, almost always occur during

January or April where there are no or few skydiving aircraft operating at the

airfield. The data does not support these conclusions.

5. Mr. Kelly admitted that accidents that would occur, either from a collision

with a turbine or turbulence, would fall within Category A of the SMS

Reports, which concludes that there is potential for loss of life or

destruction of property and equipment.

6. The SMS Report makes it clear, and Mr. Kelly affirmed as current, that the

Civil Aviation Daily Occurrence Reporting System (CADORS) information

relating to skydiving injuries used in the SMS Report is not complete and

rarely used by the skydiving community.

7. There were a number of other errors in his report and testimony that call into

question the reliability of his recommendations. As related to airplane

piloting, these include but are not limited to:

a. Improper referencing.

b. Misidentifying the kind of plane used at Skydive.

c. Erroneously suggesting the obtaining of weather data for 15,000 ft when

this type of reporting does not exist.

8. Mr. Kelly agreed that he expected that pilots would follow guidelines for

safety (best practices) and not because they were prescribed by any

regulatory regime.

Submissions of the Director regarding Harm to Airplane Pilots

[83] The Director makes the following submissions:

1. The only witnesses who were qualified to provide opinion evidence on

issues relating to the impact of wind turbines T4 and T5 on aircraft flying in

and out of the Port Colborne aerodrome were Mr. Pitt for the Appellants and

Mr. Kelly for the Instrument Holder. Dr. Cox, while qualified to give opinion

evidence in the area of risk assessment in transport, focused his testimony

on the risk to skydivers.

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

28

2. Mr. Kelly concluded that both under normal operations and in the case of an

aircraft emergency (e.g. loss of engine power), there is no additional risk to

aircrafts related to wind turbines T4 and T5.

3. Mr. Kellys evidence should be given considerable weight by the Tribunal

since he provided detailed pathways for his conclusions including data,

assumptions and analysis. In contrast, Mr. Pitts evidence should be given

no weight since he provided no evidence to support his opinion that wind

turbines T4 and T5 will leave the pilot with not a lot of room for error in an

emergency situation.

Submissions of the Approval Holder regarding Harm to Airplane Pilots

[84] The Approval Holder relies on Mr. Kellys evidence regarding Transport Canada

Regulations, and makes the following submissions:

1. The wind turbines are stationary objects which cannot be the cause of a

collision.

2. The only evidence put forward by the Appellants of a risk of collision with

the plane was through Mr. Pitt, whose evidence, for the reasons set out

above, should be given no weight. Nonetheless, even if given any weight,

the evidence provided by Mr. Pitt is not sufficient to demonstrate that the

turbines will cause harm with respect to airplanes.

3. The evidence clearly indicates that the airplanes engaged in normal flight

will have more than sufficient clearance from wind turbines T4 and T5. The

evidence demonstrates that the circuit flown can be, and is, altered on a

regular basis, depending on daily wind circumstances, which means that

when flying in the circuit the plane is further away from the area of wind

turbines T4 and T5 than first asserted by Mr. Pitt. The evidence also

demonstrates that there are more than enough alternate landing areas in

the event of an emergency such that there is no real evidence that the

turbines will cause harm in such circumstances.

4. The risks involved in take-off and landing are primarily due to engine or

mechanical failure or from incidents related to turbulence. The Appellants

presented no evidence that either of these circumstances is likely to exist or

that even if they do, that they are caused by turbines T4 and T5.

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

29

5. The Appellants, through Mr. Pitt, provided inconsistent evidence regarding

necessary plane movements. He confirmed that the circuit flown is variable,

even within the Visual Flight Rules and the diagram set out at as an

attachment to Mr. Pitt's witness statement, Mr. Pitt confirmed that

sometimes the airplane he pilots is actually flying in different locations, with

lots of clearance over the area of the turbines and that the circuit diagram

he prepared is simply what he "usually does". Mr. Pitt, in response to the

question of whether there is deviation in judgement involved in flying the

circuit, confirmed that the circuit flown depends on the wind.

6. It is a pilot's responsibility to avoid objects and for some reason the

Appellants, through these appeals and through their position, are

advocating to have that responsibility put on the proponent to require that

obstacles are not put in the way of pilots or their aircraft.

7. There is simply no evidence to support a finding that turbines T4 and T5

"can be" the cause of any harm let alone "will cause" harm to human health

with regard to airplanes and collision. As such, this element of these

appeals must fail.

Findings Respecting Serious Harm to the Health of Skydives Airplane Pilots

[85] It is not disputed that an airplane pilot would suffer serious harm to his/her health

in the event that the plane collides with another object or crashes into the ground. The

Appellants assert that such will occur if a plane collides with wind turbines T4 or T5, or if

a plane is unable to safely fly if exposed to wind turbulence generated by these wind

turbines. The Appellants also rely on the Aeronautical Information Manual in support of

their position that the safe and efficient use of an aerodrome can be seriously eroded by

the presence of obstacles within or close to the take-off or approach areas.

Aeronautical Information Manual

[86] The Tribunal begins with the excerpt quoted by Mr. Pitt from s. 4 of the

Aeronautical Information Manual which speaks to obstacle restrictions. It states:

4.1 GENERAL

The safe and efficient use of an aerodrome, airport or heliport can be

seriously eroded by the presence of obstacles within or close to the take-

off or approach areas. The airspace in the vicinity of takeoff or approach

areas (to be maintained from obstacles so as to facilitate the safe

operation of aircraft) is defined for the purpose of either:

a) Regulating aircraft operations where obstacles exist;

Environmental Review Tribunal Decision: 13-121/13-122

Pitt v. Director,

Ministry of the Environment

30

b) Removing obstacles; or

c) Preventing the creation of obstacles.

4.2 OBSTACLE LIMITATION SURFACES

An obstacle limitation surface establishes the limit to which objects may

project into airspace associated with an aerodrome and still ensure that

aircraft operations at the aerodrome will be conducted safely. It includes

a take-off/approach surface, a transitional surface and an outer surface.

[87] The excerpt also includes a diagram entitled Obstacle Limitation Surfaces which

maps, in three dimensions, the three surfaces referenced above. This diagram is

immediately followed by a new section 4.2.2, relating to heliports. Therefore, there is no

further explanation of how the diagram is to be used.

[88] In cross-examination, counsel for the Director put the following assertion to Mr.

Pitt, who made the following response:

Q. So really my point to you Mr. Pitt, nowhere in here does it say every