Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dolomites

Uploaded by

oliversmithwriting0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

248 views5 pagesThe Italian Dolomites are rich in legends - dwarves, witches, ogres and dragons are said to stomp about the slopes. Lofty peaks conceal hidden passages to the underworld.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe Italian Dolomites are rich in legends - dwarves, witches, ogres and dragons are said to stomp about the slopes. Lofty peaks conceal hidden passages to the underworld.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

248 views5 pagesDolomites

Uploaded by

oliversmithwritingThe Italian Dolomites are rich in legends - dwarves, witches, ogres and dragons are said to stomp about the slopes. Lofty peaks conceal hidden passages to the underworld.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

The Italian Dolomites are rich in legends dwarves,

witches, ogres and dragons are said to stomp about

the slopes, and lofty peaks conceal hidden passages

to the underworld

WORDS OLIVER SMITH l PHOTOGRAPHS MATT MUNRO

Legends

of the Pale Mountains

TheSassolungo

mountainrange, as

viewedfromtheAlpedi

Siusi cablecar station

abovethetownof Ortisei

Lonely Planet Traveller August 2012 78 August 2012 Lonely Planet Traveller 79

HE CHURCH BELLS

chime noon in the Val

Badia, and Michil

Costa sits outside his

hotel in his home

village of Corvara,

studying a tattered

road map through a

cloud of cigar smoke.

The whirring of cable

cars sounds in the

distance as he leans forward and rings a point on

the map with a blunt blue crayon. This is where

witches were said to gather on summer nights,

he says. Whether youll see them there these days,

I couldnt say...

With a felt ower in his top pocket, a penny-

farthing in his backyard, a penchant for quoting the

Dalai Lama and fondness for hiking long distances

barefoot, Michil Costa certainly isnt your average

Italian hotelkeeper. And yet somehow, amid the

fantastical landscapes of the Dolomites, this eccentric

behaviour seems to have its own curious logic.

The mountains around us might have been

Tolkiens blueprint for Middle Earth this is a land

of soaring rock spires seemingly suspended above

the clouds and ramshackle farmsteads huddled

fearfully on the pastures below. For centuries, these

peaks served as mighty ramparts, shielding valley

dwellers from invaders, protecting ancient customs

and, above all, preserving legends as old as anyone

might dare to guess. Passed down over generations,

the legends of the Dolomites read like fairytale

accident reports. To leave your front door was to risk

getting bludgeoned by an ogre, harassed by a dragon

or transformed into something rather unsavoury by

The mountains

around us might

have been Tolkiens

blueprint for

Middle Earth

The village of Santa

Maddalena inVal di Funes,

withthe Odle range seen

rising above the clouds

a witch. Long before Christianity arrived here, they

were a way of explaining the origins of the

landscape; one famous story tells how the mountains

acquired their pale colour after a visiting princess

from the moon required that they be whitewashed

to ease her homesickness. Another tells of a clumsy

wizard who caused a rainbow to collapse into the

Lago di Carezza, a lake which still glows a luminous

green to this day. These tales offered glimpses of a

hidden life in the mountains above of summits that

were always in sight of humans living in the valleys,

but were forever out of reach.

Im not saying I believe in these stories, says

Michil. But theres always an element of reality to

the myths. Its a connection with the land that most

of us have lost these days.

He grins mischievously, before reaching into

his pocket to produce two small r cones. Ive

borrowed these from the elves. I put them in my hat

for good luck, but if I ever think bad thoughts I must

return them else the elves will play tricks on me.

For most locals, however, the practical

application of these stories has diminished over

time. Since tourism came to the Dolomites in the

19th century, skiers have displaced sorcerers and

elves have lost ground to exclusive resorts.

Grandparents grumble that youngsters today are too

preoccupied with PlayStations to be scared by the

witches who roam the slopes outside their bedroom

windows. Yet the stories are still an indelible part of

the landscape: to walk almost anywhere in the

Dolomites is to trespass on a witches coven, or to

unwittingly scale mountains hollowed out by

communities of dwarves.

Michil swoops down on the map and marks out

a lake at the northern edge of the Parco Naturale

above Michil Costa, anauthorityonthecultureandtraditions

of theDolomites, outsidethe Hotel LaPerlainCorvara

Lonely Planet Traveller August 2012 80 August 2012 Lonely Planet Traveller 81

THE DOLOMI TE S

M

A

P

IL

L

U

S

T

R

A

T

IO

N

: A

L

E

X

A

N

D

R

E

V

E

R

H

IL

L

E

. C

O

P

Y

IL

L

U

S

T

R

A

T

IO

N

S

: K

A

T

E

M

C

L

E

L

L

A

N

D

di Fanes-Sennes-Braies a windswept plateau rearing

up behind sheer walls of rock, a few miles to the

northeast of Corvara. Legend tells that Lago di Braies

hides a secret gateway into the underworld. They say

if you visit when the moon is full, the mountains shall

open up and a boat will appear carrying a princess...

I dont know if thats true, he says with a shrug,

pocketing the r cones. Ive never tried to nd out.

RICA CLEMENT

drops a stful of dough

onto her kitchen table

with a satisfying

thwack. Nonsense,

she says. We dont

believe in fairytales

we are sensible folk

up here.

A half-timbered

farmhouse standing

on an outcrop further up the valley from Corvara,

Sotciastel does indeed look like a sensible place:

piles of logs are stacked neatly by the porch, while

tidy lawns sparkle with the morning dew. Inside,

little has changed since Ericas ancestors built their

home in these mountains more than two centuries

ago. Pious sentiments are inscribed on creaking

doors and wooden oorboards groan wearily

underfoot. For the past two decades, Erica has

opened the doors of her home to staying guests.

Wednesday mornings see visiting cookery students

joining them, shufing into a small kitchen to take

notes as Erica prepares stews, dumplings and

doughnuts on an old wood-burning stove.

It doesnt matter what sort of cheese you use for

dumplings, Erica sagely tells her students, reaching

A legend tells of a wizard who caused a rainbow to collapse

into the Lago di Carezza, which still glows a luminous green

Fed by underground springs, Lago di Carezza is known inthe Ladin language as The RainbowLake

for a cheese grater. Just as long as the cheese stinks.

Food here is intended as fuel for long days slogging

up steep inclines protein-rich staples served in

mountain-like portions. It represents a culture distinct

from Mediterranean Italy. Despite living in a largely

German-speaking corner of the country, Erica counts

herself as Ladin a community whose mother tongue

descends from the Latin spoken by Roman legionaries

who marched through these valleys millennia ago.

Europe was once a jigsaw puzzle of smaller

languages like Ladin. As others disappeared, Ladin

clung on a tiny Romance language that evolved in

parallel to French and Italian, wedged between the

Italian- and German-speaking worlds. Ladin history

celebrates deant heroes, such as a 16th-century

nobleman who rescued villagers from a marauding

dragon, and a 19th-century housewife who

defended her village against Napoleons armies,

wielding a pitchfork. Bolstered by a ve-minute

Ladin daily slot on TV and a page in the regional

newspaper, native speakers today number more

than 30,000. A peculiar mix of Italian-sounding

cadences and glottal Germanic stops, it is the

language in which many of the Dolomites most

famous legends are preserved.

Were not like the Italians were much more

practical, says Erica, heaping splinters of wood onto

a raging re beneath the stove. For instance, whats

the point in wasting time eating lots of different

courses for dinner? You may as well eat everything

all in one go!

Ladin legends also seem sternly pragmatic. One

tale tells of a amboyant peasant who drank too

much grappa and marched up a mountain to

vanquish an ogre. The disgruntled monster

catapulted him across a mountain for his cheek.

fromleft EricaClement making afresh batchof doughnuts in her kitchen inSotciastel; Erikas home, perched onthe slopes

above Val Badia a Ladin-speakingvalley that serves as the settingfor many legends

August 2012 Lonely Planet Traveller 83 Lonely Planet Traveller August 2012 82

THE DOLOMI TE S

The peasant learned never to try anything so daft

again. I step out of Sotciastel farmhouse and into the

morning sunshine. Cows watch eecy clouds pass

along the valley below, and old tractors wheeze their

way up the hillsides. Erica dusts her hands on her

apron as she bids me farewell. If you really are

looking for witches and the like, she says, Im afraid

youll have to go much higher up.

HE LANDSCAPE

turns crueller as I climb

into the Fanes National

Park and towards Lago

di Braies. Meadows

rise to barren

precipices, and pine

trees begin to lose their

foothold in the scree.

Traces of civilisation

become scarcer: I pass

a wooden crucix clinging to a wind-battered

outcrop, and ruined cottages where wildowers

sprout among the stones. Black clouds hover grimly

around the summits, periodically sending

thunderclaps booming down the valleys below.

Hard though it may be to believe, these mountains

were once coral reefs, prised up from the seabed

when the European and African tectonic plates

collided more than 50 million years ago. Today,

fossilised sea creatures are sometimes found at

altitudes where humans rarely venture. It was only

in the mid-19th century that climbers rst began to

explore the Dolomites in earnest. Early mountaineers

encountered what they described as petried castles

and Gothic cathedrals built of rock buttress-like

ridges, and towers of biblical proportions. The Swiss

fromleftAwoodencrucix standingon a hilltopclose to the townof Selva inVal Gardena; woodcarver Siegfried Meyr

whittles away at atree trunk by the side of a mountain road

architect Le Corbusier even went so far as to call them

the nest natural architecture in the world.

Yet for generations of valley dwellers, going for a

walk in these mountains was asking for trouble to

risk man-guzzling crevices and falling rocks that

could bowl humans off the mountainside like

skittles. It was against this backdrop of fear that

legends of the Dolomites took root.

My ears pop as the trail wriggles its way up the

mountainside and into the clouds. I pass upturned

trees whose roots claw ominously towards the sky,

and spy a bird of prey gliding about the crags below.

In this landscape, it takes little imagination to trace

wrinkled faces in the rock or to hear the rustle of

a chamois in the undergrowth and mistake it for

something decidedly more sinister.

The plateau up ahead was the setting for one of the

oldest and strangest of all the Ladin legends.

The story goes that long ago the Fanes inhabited this

region a people besieged by enemies from all sides,

but loyally defended by a warrior princess with a

quiver of unstoppable arrows. After many battles,

the princess lost her arrows, and the king

of the Fanes betrayed his people to their enemies

in exchange for a hoard of treasure. Their castles

captured and their kingdom lost, a small band of the

Fanes were rescued by marmots animals said to be

the guardians of the underworld and taken down

into the bowels of the Earth.

Experts date this tale as far back as the Bronze Age,

when warmer climates meant people could survive

high up on the Alpine plateau. Until little more than

a century ago, hunters from these valleys would

make a point of refusing to kill marmots,

and shepherds were said to shelter these creatures

beneath their huts.

For valley dwellers,

going for a walk

in the mountains was

asking for trouble

Asummer storm gathering above the

forested slopes of Val Badia

Lonely Planet Traveller August 2012 84 August 2012 Lonely Planet Traveller 85

THE DOLOMI TE S

IGHT SETS IN AS I

approach Lago di

Braies a cauldron-

like body of water

with the mountain

of Sass dla Porta

hunched at its

southern edge. The

Fanes legend has it

that once every

hundred years, a

princess emerges from the Sass dla Porta to row

around the lake beneath the full moon. She awaits

the day when someone will return the unstoppable

arrows to the Fanes people when trumpets will

sound across the Dolomites and the glory of her

kingdom will be restored for eternity. Sass dla Porta

translates from Ladin as Gate Mountain. Some say a

cavern once stood at its foot before landslides buried

the passage presumably grounding the princess,

and postponing forever the return of her kingdom.

The torches of departing shermen fade on the

lakes far side, and all is still. Except for the distant

clunking of cowbells sounding from the darkness,

nothing stirs. Seeing the phantom-like outline of the

Dolomites against the night sky, it feels harder to

sneer at stories of witches, sorcerers and secret gates

to the underworld. Perhaps these legends are the

last reminders of a time when we didnt need to

believe in heaven and hell the landscape was

mysterious enough in itself. I swim out into the lake,

and only the plop of leaping sh and the murmur of

a faraway waterfall break the silence.

Once every hundred years, a princess emerges to row

around the lake beneath the full moon

Lago di Braies at midnight, withthe Sass dla Porta mountain rising into the skies

OliverSmithis staff writer at LonelyPlanetTraveller. After

swimming in Lagodi Braies for two minutes, he got into his car,

put onthe heating and spent two hours tryingtowarmup.

aboveAsculpture mounted on a house inVal Gardena, a Ladin

valley renowned for its wood-carving artisans

Andrew Graham-Dixon and Giorgio Locatelli look at

art, culinary culture and landscapes in NorthernItaly

Unpacked, coming soon to BBCTwo.

August 2012 Lonely Planet Traveller 87 Lonely Planet Traveller August 2012 86

THE DOLOMI TE S

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- ARCHITECT PHILIPPINES Outline Spec For ArkiDocument39 pagesARCHITECT PHILIPPINES Outline Spec For ArkiBenjie LatrizNo ratings yet

- TunisiaDocument5 pagesTunisiaoliversmithwritingNo ratings yet

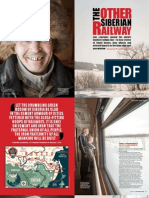

- The GhanDocument4 pagesThe GhanoliversmithwritingNo ratings yet

- Take Back Roads Past Deep Green Paddy FieldsDocument6 pagesTake Back Roads Past Deep Green Paddy FieldsoliversmithwritingNo ratings yet

- PolandDocument4 pagesPolandoliversmithwritingNo ratings yet

- OmanDocument12 pagesOmanoliversmithwritingNo ratings yet

- IcelandDocument4 pagesIcelandoliversmithwritingNo ratings yet

- Beyond: The Perfect TripDocument6 pagesBeyond: The Perfect TripoliversmithwritingNo ratings yet

- Of The Lunatic ExpressDocument6 pagesOf The Lunatic ExpressoliversmithwritingNo ratings yet

- RussiaDocument5 pagesRussiaoliversmithwritingNo ratings yet

- Vietnam: The Perfect TripDocument7 pagesVietnam: The Perfect Tripoliversmithwriting100% (1)

- Indah Water QADocument5 pagesIndah Water QAliewkitkongNo ratings yet

- Saying Hello and Good Bye: Formal and Informal WayDocument6 pagesSaying Hello and Good Bye: Formal and Informal WayPatricia RojasNo ratings yet

- Chirag BhoirDocument77 pagesChirag BhoirSanchit PawarNo ratings yet

- Rephrasing+2014 2015Document4 pagesRephrasing+2014 2015Aída MartínezNo ratings yet

- Greater Romulus Chamber of Commerce September 2012 NewsletterDocument8 pagesGreater Romulus Chamber of Commerce September 2012 NewslettergordhoweNo ratings yet

- RP 48.000.000 For 300 Pax: Buffet SelectionDocument2 pagesRP 48.000.000 For 300 Pax: Buffet SelectionGrida ViantiskaNo ratings yet

- 162 Sample-ChapterDocument24 pages162 Sample-ChapterQayes Al-QuqaNo ratings yet

- Croatia 5 KvarnerDocument37 pagesCroatia 5 KvarnermumikaNo ratings yet

- PMR English Language Module 1 Paper 1Document21 pagesPMR English Language Module 1 Paper 1eric swaNo ratings yet

- Banquet Liability Form 2023Document1 pageBanquet Liability Form 202321 Cafe IloiloNo ratings yet

- Ermita Malate Hotel and Motel Operators Vs City of ManilaDocument2 pagesErmita Malate Hotel and Motel Operators Vs City of ManilaWilliam Azucena100% (1)

- Prepare Beds and Handle LinenDocument21 pagesPrepare Beds and Handle Linenddmarshall2838No ratings yet

- North Coast 5-23Document32 pagesNorth Coast 5-23mdola518No ratings yet

- India in MapsDocument2 pagesIndia in MapsRenu SehraNo ratings yet

- Public Area Cleaning: Institute of Hotel Management KolkataDocument8 pagesPublic Area Cleaning: Institute of Hotel Management KolkataNaruto UzumakiNo ratings yet

- How To Relax and Where To StayDocument16 pagesHow To Relax and Where To StaydanikNo ratings yet

- English IV: Than BillDocument3 pagesEnglish IV: Than BillJuan RosalesNo ratings yet

- Ra 7160Document49 pagesRa 7160Eriellynn LizaNo ratings yet

- Pierre Jeanneret Private ResidencesDocument21 pagesPierre Jeanneret Private ResidencesKritika DhuparNo ratings yet

- CV Bhavuk Singhal PDFDocument2 pagesCV Bhavuk Singhal PDFMahesh Jajoo0% (1)

- Previous Paper DMRCL Asst Manager Section Officer General English Paper IIDocument6 pagesPrevious Paper DMRCL Asst Manager Section Officer General English Paper IISatyendra ShgalNo ratings yet

- Opera Training For Front OfficeDocument18 pagesOpera Training For Front OfficeHichem LaouerNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 IBS Integrated Building SystemDocument34 pagesChapter 2 IBS Integrated Building SystemMohd Afzal0% (2)

- The Response To Our New Employee Seminar Was Very Encouraging - The Management Decided To Offer Another Session Next WeekDocument40 pagesThe Response To Our New Employee Seminar Was Very Encouraging - The Management Decided To Offer Another Session Next WeekQúy TỏiNo ratings yet

- Tour Package 01Document24 pagesTour Package 01Dinithi NathashaNo ratings yet

- WP 2 2 1 Energy ManagementDocument57 pagesWP 2 2 1 Energy ManagementVidyanand ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Business Etiquette in BriefDocument4 pagesBusiness Etiquette in BriefdahmailboxNo ratings yet

- Yangon Property Market Report 1 H 2012Document71 pagesYangon Property Market Report 1 H 2012Colliers International Myanmar100% (1)

- Mathematics in The Modern World: Relationship of Tourism and HospitalityDocument5 pagesMathematics in The Modern World: Relationship of Tourism and HospitalityJen Jane Estrella PardoNo ratings yet