Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Egypt - African Economic Outlook

Uploaded by

Andre' EaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Egypt - African Economic Outlook

Uploaded by

Andre' EaCopyright:

Available Formats

Egypt

Economic growth has softened, the scal and balance-of-payments decits have deteriorated, and foreign

exchange reserves have fallen to a critical minimum level.

Two years after the Arab Spring uprising, Egyptians many of whom are living below the poverty line are still

waiting to reap the full benefits of lasting social, political and economic change.

Egypt has potential both for structural transformation towards a more productive economy and for optimal use

of its immense resource wealth, provided that vital policy reforms are introduced.

Overview

After toppling Hosni Mubarak in February 2011, Egyptians celebrated the election of Muslim Brotherhood

candidate Mohammed Morsi on 24 June 2012, as the countrys rst democratically elected president. A new

constitution, drafted by an Islamist-dominated assembly and narrowly approved in mid-December 2012 by

voters, has dramatically divided the country. A new parliament is expected to be in place later in 2013,

following elections starting in April to replace the Islamist-dominated body that was dissolved by the Supreme

Constitutional Court in June 2012.

As Egyptians wait to complete the transition to democratic government, they still face a number of challenges.

The real gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate fell to 2.2% in the scal year ending June 2012, down from

5.1% in 2009/10, before the revolution. Continued political instability has undermined inows from tourism and

foreign direct investment (FDI). Economic growth is expected to remain depressed, at about 2% as of June

2013.

Delay in agreement about USD 4.8 billion in nancing from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which would

be subject to conditions to increase taxes and reform subsidies and public employment, has pushed Egypt to the

verge of a full-blown currency crisis. By end-January 2013, the Egyptian pound (EGP) had depreciated by over

12.5% of its value since the uprising. The market expects the pound to depreciate further, to between EGP 7

and EGP 7.50 to the US dollar, and a black foreign exchange market is emerging. In June 2012, Egypts

domestic debt and scal decit reached 80.3% and 10.8% of GDP respectively, narrowing the room for scal

manoeuvre.

Poverty remains high, with 25.2% of the population living on less than USD 1.5 per day in 2010/11. The

illiteracy rate is high at 27%, and there are wide income disparities. The Egyptian statistical agency reported

that unemployment was 12.5% in the third quarter of 2012, although several sources indicate that the

unemployment rate may actually be above 18%. Over 3.3 million Egyptians are unemployed, while the

unemployment rate for 20- to 24-year-olds is 46.4%.

The government is working to address several of the structural and institutional problems that beset Egypt. It

has developed a home-grown programme to reform the inecient energy subsidy system and is promoting

policies to ght corruption, foster societal inclusion and enhance equality of opportunity. However, the

governments reluctance to accept the IMF conditions before the elections of April 2013 reects the diculty of

implementing necessary but unpopular entitlement reforms in a heavily divided society.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932805213

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932808196

Figure 1: Real GDP Growth 2013 (North)

Figures for 2012 are estimates; for 2013 and later are projections.

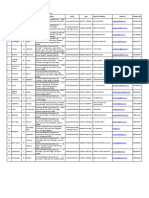

Table 1: Macroeconomic indicators

2011 2012 2013 2014

Real GDP growth 1.8 2.2 2 3.5

Real GDP per capita growth 0.1 0.5 1.2 3

CPI inflation 11.1 8.7 10.6 11.7

Budget balance % GDP -9.7 -10.8 -11.4 -9.9

Current account % GDP -2.6 -3.3 -3.1 -2.4

Figures for 2012 are estimates; for 2013 and later are projections.

Real GDP growth (%) Northern Africa - Real GDP growth (%) Africa - Real GDP growth (%)

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

-2%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

R

e

a

l

G

D

P

G

r

o

w

t

h

(

%

)

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932809184

Recent Developments & Prospects

Table 2: GDP by Sector (percentage of GDP)

2007 2012

Agriculture, forestry & fishing 14.1 14.8

Agriculture, hunting, forestry, fishing - -

Construction 4.1 4.6

Electricity, gas and water - -

Electricity, water and sanitation 1.9 1.7

Extractions 15.5 15.5

Finance, insurance and social solidarity 10.4 9.6

Finance, real estate and business services - -

General government services 9.8 10.4

Gross domestic product at basic prices / factor cost 100 100

Manufacturing 17 16.2

Mining - -

Other services - -

Public Administration & Personal Services - -

Public Administration, Education, Health & Social Work, Community, Social & Personal Services - -

Public administration, education, health & social work, community, social & personal services - -

Social services 2.8 3.9

Transport, storage and communication - -

Transportation, communication & information 10.3 9

Wholesale and retail trade, hotels and restaurants - -

Wholesale, retail trade and real estate ownership 14.2 14.4

Since the revolution of 25 January 2011, Egypt has experienced major political challenges and a period of

transition to democracy. Despite the election of Mohammed Morsi in June 2012, as the rst democratically

elected president, political stability remains elusive. Riding high on the praise he earned at home and abroad for

brokering a truce between Israel and Hamas in Gaza, President Morsi issued a constitutional declaration in

November 2012, awarding himself broad powers above judicial scrutiny. This led to nationwide protests by his

opponents, which were in turn violently countered by his supporters. Although the president later retracted

that decision, a new constitution drafted by an assembly dominated by the Muslim Brotherhood and its allies,

and approved by a narrow majority of 63.8% in a referendum that saw a voter turnout of 32.9% left the

country deeply divided politically.

Despite the political upheaval, Egypts stock market performed relatively well compared to other emerging

markets, posting returns of over 45% in 2012. However, the prolonged political transition has hindered

economic growth. Real GDP growth has not returned to the pre-revolution rate of over 5.1% in scal year

2009/10. The growth rate accelerated slightly in 2011/12 to 2.2%, as against 1.8% in the previous scal year.

Although the parliamentary elections scheduled for early 2013 will mark the end of the transition period,

economic growth is expected to remain subdued at about 2% when the scal year ends in June 2013 and pick

up to 3.5% by June 2014. On the demand side, economic activity during 2011/12 was driven by private and

public consumption, which compensated for declining investment and a widening trade decit. Total private and

public consumption accounted for 90.9% of GDP and investment for 15.3% in 2011/12, compared to 87% and

16.7% respectively in the previous year. Egypts economic growth was driven in particular by private

consumption, which rose to 79% of GDP in 2011/12 compared to an average of 73.7% over the 2005-11 period.

Finally, exports and imports stood respectively at 12.9% and 22.2% of GDP in 2011/12, compared to 11.7% and

23.5% in 2010/11.

At the sectoral level, the main contributors to GDP growth in 2011/12 were agriculture (2.9% growth, 14.8% of

GDP), construction (3.3% growth, 4.6% of GDP), telecommunications (5.2% growth, 4.4% of GDP) and real

estate (3.2% growth, 2.9% of GDP). In contrast, poor performance in the manufacturing and tourism sectors,

which expanded weakly at 0.7% and 2.3% respectively, weighed heavily on GDP growth in 2011/12; in

2009/10, before the revolution, these sectors had posted growth of 5.1% and 12% respectively.

Egypts foreign income earning has been undermined by Europes economic distress, unfavourably impacting

the balance of payments. Merchandise exports, which went primarily to Europe, Egypts main trading partner,

decreased by about 0.1% to USD 27 billion in both 2010/11 and 2011/12, more than 8% below the level

achieved in 2007/08. Tourism has been hard hit by political instability, security problems and border attacks in

Sinai. As a result, tourism revenues decreased by 11% to USD 9.4 billion (3.1% of GDP) in 2011/12. Suez Canal

receipts stabilised at about USD 5 billion (2.1% of GDP) in 2010/11 and 2011/12, a rather positive development

given the downward trajectory in canal revenues in the four previous fiscal years.

Net foreign direct investment (FDI) inows declined for the fourth year in a row, levelling o at about

USD 2.1 billion (0.8% of GDP) in both 2010/11 and 2011/12, down from a peak of USD 13.2 billion (8% of GDP)

in 2007/08 prior to the global nancial crisis. In 2011/12, net private transfers (mainly Egyptian workers

remittances) amounted to USD 18 billion (7% of GDP), up 43% from the previous scal year. Remittances from

Egyptian workers abroad have been on an upward trend since 2007/08.

Total investment (excluding changes in inventory) reached USD 39 billion (15.3% of GDP) in 2011/12. Crude oil

and natural gas attracted the largest investments (approximately 25% of the total), followed by transportation

and communication (19%) and housing and real estate (16.7%). Manufacturing and petroleum products attracted

8.7% of total investment, while health and educational services received only 1.6% and 2.4% respectively.

The economy has suered from the climate of uncertainty as the political crisis has deepened and the stando

between the executive and judiciary has worsened. Crucial tax increases and austerity measures that are

conditions for the IMF loan were postponed because of the political unrest that followed President Morsi's

decision to fast-track implementation of the new constitution. While such adjustments could depress domestic

demand, their postponement means that Egypt will continue to be unattractive for foreign direct investment.

Furthermore, the economy is suering from high interest rates on government bonds: the three-month treasury

bill (T-bill) rate spiked to a monthly average of 13.1% in June 2012, up from 11.5% a year earlier. These high

rates are partly to blame for driving the fiscal deficit to unsustainable levels.

Furthermore, a currency crisis is looming. Egypts net international reserves have dropped to a critical minimum

that barely covers three months of imports (USD 13.6 billion as of end-January 2013). Foreign reserves

averaged USD 35 billion during the three scal years preceding the revolution. The local currency shed over

4.5% of its US dollar value in a few weeks in January 2013 and has fallen by more than 10% since the

revolution. As anxious Egyptians rush to buy dollars in the wake of the currencys fall, the dollarisation ratio in

households is bound to rise above the 15.5% level it had reached at end-October 2012.

In January 2013, Qatar bolstered the Egyptian pound (EGP) by providing USD 2.5 billion, over and above an

earlier nancial package of the same amount. Nevertheless, the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE) ran down over

USD 20 billion of reserves over 2010/11 and 2011/12 to defend the local currency. The CBE has limited options

as it attempts to control a slow depreciation of the pound.

As social unrest persists and the population continues to grow, Egypts social and human development

challenges continue to mount. About 20 million Egyptians live on less than USD 1.5 a day, and over 3.3 million

are unemployed.

Egypts need for external nancing is urgent. The IMF estimates the gap at USD 14.5 billion. In January 2013,

the IMF and Egypt resumed talks to move forward a November 2012 sta level agreement that had been

postponed due to the political unrest that emerged when President Morsi fast-tracked the contentious new

constitution. The IMF nancing package amounts to USD 4.8 billion and would mobilise additional lending from

other multilateral and bilateral development partners. The scal reforms demanded from Egypt as conditions for

the loan have proven challenging for the government, owing to the countrys current state of social and political

division. It is unlikely that an agreement will become effective before the new parliament is in place.

Macroeconomic Policy

Fiscal Policy

Egypts scal decit widened by 24% in 2011/12 to USD 27.5 billion (10.8% of GDP), from USD 22.6 billion

(9.7% of GDP) a year earlier, as the government increased spending in response to the social and political

demands of the revolutionary movement. While revenues increased by 14.5% to USD 50 billion in 2011/12,

they were outstripped by year-on-year expenditures, which rose by 17.2% to USD 77.7 billion over the same

period.

Taxes increased by 8.2% year-on-year to USD 34.2 billion in 2011/12. The main components of taxation are

taxes on incomes and prots (45%) and on consumption (40%). In 2011/12, state-owned enterprises contributed

76% of all taxes on income and prots the Egyptian General Petroleum Corporation (EGPC) alone paid 37%

while individuals contributed only 24%. Grants from foreign governments, which are part of non-tax revenue,

increased substantially in 2011/12 to USD 1.5 billion, compared to USD 0.15 billion in 2010/11.

About 80% of government spending is allocated to recurrent expenditures interest payments on public debt

(22%), wages and salaries (26%), and subsidies, grants and social benets (32%) rather than to capital goods.

Public investment spending, which averaged 4% of GDP in 2009/10, before the revolution, contracted to 2% of

GDP (USD 6 billion) by end-June 2012. As of June 2012, interest on government debt had risen by

USD 2.8 billion year-on-year to USD 17 billion (8.9% of GDP). Interest on domestic debt accounts for 97% of

total interest payments paid by the government. Subsidies to consumers (71% of which are for energy products,

the rest for food items), increased by USD 3.9 billion year-on-year to reach USD 22.4 billion by end-June 2012.

To contain the growing scal decit to about 9.9% of GDP in 2013/14, the government is cutting energy

subsidies and raising taxes. The 2012/13 budget proposed a USD 12 billion reduction in petroleum products

subsidies, but midway through the scal year much of this reduction has not yet been implemented. Electricity

rates have been raised, however, and the subsidy on high-grade 95-octane petrol was eliminated in November

2012. Cutting this subsidy may bring only negligible savings, as users could shift demand to subsidised 92-octane

petrol, but it is a positive development that Egyptians are now openly discussing the need for reforms to the

inecient energy subsidy system (the low eciency of subsidies generally is discussed below, in the Social

Context and Human Development section).

Egypt is mobilising further tax revenues as well. Taxes on cigarettes have been raised. The government has

announced increases in the progressivity of income taxes and aims to broaden the general sales tax into a full-

edged value added tax. However, implementation of such economic reforms remains uncertain because of the

ongoing political turmoil. A capital gains tax has been introduced on initial public oerings on the stock

exchange.

In its eort to diversify nancing away from the domestic banking sector, the government is seeking an IMF

package that would mobilise about USD 14.5 billion in loans and deposits from the IMF itself (USD 4.8 billion)

and from other bilateral and multilateral lenders. This would provide scal relief from the high interest rates on

government T-bills: the rate for three-month T-bills, for example, averaged 13.1% in June 2012, up from 11.5%

a year earlier.

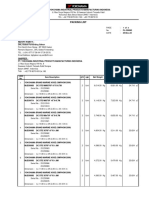

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932810172

Table 3: Public Finances (percentage of GDP)

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Total revenue and grants 27.1 21.6 18.9 18.6 18.2 18.1

Tax revenue 15.3 13.4 13.8 13.3 13.1 12.7

Oil revenue 10.7 7.5 4.8 4.8 4.8 4.8

Grants - - - - - -

Total expenditure and net lending (a) 33.7 29.4 28.6 29.4 29.7 28

Current expenditure 29.6 25.5 25.8 26.6 26.8 25.2

Excluding interest 24.5 19.7 17.6 17.7 18.1 17.4

Wages and salaries 7.3 6.9 6.9 6.7 6.3 5.8

Interest 5.1 5.8 8.3 8.9 8.8 7.8

Primary balance -1.6 -2.1 -1.4 -1.9 -2.6 -2.1

Overall balance -6.6 -7.9 -9.7 -10.8 -11.4 -9.9

Figures for 2012 are estimates; for 2013 and later are projections.

Monetary Policy

Since 2004, Egypt has pursued a managed oat exchange rate regime that aims to hold the rate at EGP 6 to the

US dollar. With the onset of the political crisis, this policy has been increasingly dicult to maintain in the face

of a sharp drop in foreign earnings and capital inows. As a result, in January 2013 the exchange rate fell to

over EGP 6.5 to the dollar, and net international reserves (used by the CBE to support the exchange rate),

dropped by end-January 2012 to USD 13.6 billion, from USD 26.6 billion in June 2011.

Current foreign reserves held by the CBE cover just about three months of imports, which the central bank

considers to be a critical minimum. The CBE has said that the remaining reserves would be used only to nance

external debt service, cover strategic imports and respond to emergencies. The central bank therefore

introduced currency auctions and other foreign currency controls in December 2012. Support from the IMF is

now needed urgently if Egypt is to avoid a disorderly domestic currency devaluation that would trigger higher

food prices and further social unrest.

Interest rates have been maintained at their November 2011 level (overnight deposit rate, 9.25%; discount

rate, 9.5%; overnight lending rate, 10.25%; and seven-day repo rate, 9.75%). This represents a delicate trade-

o between the need to revitalise growth (with lower interest rates) and the need to curtail inationary

pressures (with higher interest rates). The interest rate adjustments of November 2011 caused the above-

mentioned spike in the three-month T-bill rate. As of June 2012, yields on one-year T-bills were about 14.8%,

compared to 11.5% a year earlier, and they have continued to rise, reaching 15.8% by end-August 2012. The

CBE cut reserve requirements on deposits in local banks from 14% to 12% in April 2012, and further to 10% by

end-June 2012, but this accommodative monetary policy appears to have had little impact in terms of curtailing

the rise in interest rates.

The year-on-year headline ination rate, as measured by the urban consumer price index, slowed from 11.8%

in June 2011 to 4.66% in December 2012 as economic activity continued to contract because of political unrest.

Core ination also dropped from 8.94% year-on-year to 4.44% over the same period. However, the central

bank foresees local supply bottlenecks for food and butane, and distortions in the distribution channels for food

products as inationary risks and wants to take a more proactive role in managing them. It has formed an inter-

ministerial persistent inflation group with a mandate to address directly the structural causes of inflation.

Economic Cooperation, Regional Integration & Trade

Egypts trade decit increased slightly, from USD 27.1 billion (11.8% of GDP) in 2010/11 to USD 31.7 billion

(9.2% of GDP) in 2011/12, and is no longer oset by tourism and investment receipts, now in decline. Driven by

the depreciation of the Egyptian pound and (despite incipient reforms) an inexible subsidy system for fuel and

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932811160

food, the mounting import bill of USD 58.7 billion, up 8.5% from the previous year, continued to be the driving

factor behind the decit. Overall export growth was at, as exports totalled USD 27 billion in both 2011 and

2012. Within that total, however, non-petroleum exports declined and petroleum exports increased. The

services trade balance was positive (USD 5.4 billion) but continued its stark downward trend from

USD 10.3 billion in 2009/10 and USD 7.9 billion in 2010/11. The driving factors here were declining receipts

from tourism and investment. The current account decit widened from 2.6% of GDP in 2011 to 3.3% in 2012.

Remittances from Egyptians working abroad increased by about 43% to USD 18 billion in 2012, preventing

further deterioration of the current account position.

The European Union (EU) continues to be Egypts major trading partner, absorbing USD 11 billion of Egypts

exports and supplying USD 19.3 billion of its imports in 2011/12. Within the EU, Italy accounts for the largest

share (20.7%) of merchandise exports. Between 2007/08 and 2010/11, the EU accounted for an average of 36%

of merchandise trade, the United States for 10%, and the Arab world and Asia for a fth, while Africa (excluding

Arab countries) accounted for only 2% of exports and 1% of imports. Since the revolution, the authorities have

stepped up eorts to deepen the Egyptian private sectors participation in infrastructure projects in the rest of

Africa and to support training and capacity-building initiatives on the continent.

Investment has suered from heavy short-term and long-term capital outows. Net portfolio investment

doubled its negative balance in 2011/12 to USD 5 billion. The net FDI balance remained positive at USD 2 billion

(0.8% of GDP), but outows have doubled over the last two years to USD 9.7 billion, compared to inows of

USD 11.8 billion. The EU accounted for 82% of gross FDI inflows to Egypt in 2011/12.

Table 4: Current Account (percentage of GDP)

2004 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Trade balance -10 -13.4 -11.4 -11.8 -9.2 -8.1 -7.3

Exports of goods (f.o.b.) 13.4 13.4 10.8 11.7 12.9 13 12.8

Imports of goods (f.o.b.) 23.4 26.8 22.2 23.5 22.2 21.1 20.1

Services 9.6 6.6 6.7 6 3.6 3.4 4.3

Factor income -0.3 0.1 -2 -2.6 -2.6 -2.6 -2.8

Current transfers 5 4.4 4.7 5.8 5.2 4.4 3.9

Current account balance 4.3 -2.3 -2 -2.6 -3.1 -2.9 -2

Figures for 2012 are estimates; for 2013 and later are projections.

Debt Policy

Egypts gross domestic debt had risen to 80.3% of GDP (USD 205 billion) by end-June 2012, from 76.2% of GDP

(USD 176 billion) a year earlier, as the government continued its policy of nancing the widening budget decit

by issuing T-bills. The stock of T-bills and bonds reached USD 178.7 billion (87% of gross domestic debt) by end-

June 2012, an increase of 18% year-on-year.

Yields on T-bills rose in 2011/12 to an average of 15%, compared to an average of 12% in 2010/11. As a result,

interest payments rose by 24% (USD 3.2 billion) to reach USD 17 billion by end-June 2012, and total

government debt service increased from USD 19.4 billion in 2010/11 to USD 23.4 billion over 2011/12. To

mitigate the increased costs of borrowing and enhance foreign reserves, the government in August 2012

launched auctions of one-year euro T-bills. The August auction saw the major banks buying EUR 513 million of

T-bills at an average yield of 3.245%, exceeding the governments expectations of EUR 400 million.

Foreign debt levels remain manageable, however, at about USD 5.7 billion in both the 2010/11 and 2011/12

scal years. The ratios of debt service to exports and debt service to current receipts stood at 6.1% and 4.4%

respectively at the end of June 2012, compared to 2005-12 historical averages of 6.6% and 5.5% respectively.

The IMF package under discussion could enable Egypt to diversify its borrowing away from reliance on

increasingly unsustainable domestic debt. Furthermore, it could enhance investor condence in the Egyptian

economy, and the rating agencies Moodys, Standard and Poors, and Fitch are expected to reverse their

downgrades of the countrys sovereign ratings.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932805213

Figure 2: Stock of total external debt and debt service 2013

Figures for 2012 are estimates; for 2013 and later are projections.

Debt/GDP Debt service/Exports

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

Economic & Political Governance

Private Sector

The private sector has accounted for 62% of GDP and employed 70% of Egypts workforce over the past ve

years. Before the revolution, Egypt suered from an overburdening bureaucracy, corruption and insucient

competition in many sectors. Favouritism, lack of transparency and protection of market segments prevailed.

Consequently, one of the demands of the revolution was an overhaul of the relationship between government

and the private sector. Although crucial for Egypts competitiveness in the long run, this demand has linked the

government-business relationship to the drawn-out process of political and legal transition, resulting in

widespread uncertainty and timid private sector investment.

Standard measures of competitiveness reflect some of these problems and uncertainties. Egypt ranked 107

th

out

of 146 economies on the World Economic Forums Global Competitiveness Index in 2012/13, down from 81

st

position in 2010/11. In the World Bank report Doing Business 2013, Egypt ranked 109

th

out of 183 economies,

down from 108

th

in 2011 but up from 110

th

in 2012. The reliability of contracts and the capacity to have them

enforced through the legal system rank among the chief concerns. Egypt ranked 144

th

out of 184 countries on

the enforcing contracts sub-index. Other major weaknesses were noted in paying taxes (145

th

place), dealing

with construction permits (155

th

) and resolving insolvency (137

th

). Egypt continues to have the highest share of

complaints about corrupt practices as major obstacles to business. Customs clearance delays have been cut,

though perceptions associated with trade facilitation remain negative. Import and export procedures remained

time-consuming in 2011 (12 days for each, according to Doing Business 2012).

Since the revolution, steps have been taken to change the situation reected in these indicators. A large

number of corruption investigations have been started and several high-prole indictments made against

business and former high-ranking ocials and ministers. Several land allocations made by the former

government through direct contracts have been withdrawn, and privatisations of former state-owned companies

in the oil and manufacturing sectors have been reversed. A special committee established to settle land disputes

with investors expects to net about USD 3.3 billion by the end of 2013. In addition, the new constitution

establishes a national anti-corruption commission.

Financial Sector

Egypts nancial sector has recovered markedly from its overextended position in 2007, but it remains

inecient at providing credit to the private sector. In 2012, the problem was the opposite of that in 2007:

uncertainty over the speed of recovery and transition led to a build-up of liquidity in banks. The loans-to-

deposits ratio stood at 49.8% by end-September 2012, and non-performing loans amounted to a comfortable

9.9% of total loans at end-June 2012. The government remains the largest borrower, squeezing credit for

private sector investment.

Accommodative monetary policy has had some eect in getting the liquidity in banks into the real sector of the

economy: credit to the private sector grew by about 7.3% between 2011 and 2012. However, deposits also

rose by 6.4% to USD 172.7 billion. Insucient access to nance was rated among the top obstacles to business

growth by rms in the 2008 Enterprise Survey of Egypt. The government has sought to increase nancing for

the private sector. In 2010, access to credit information was expanded with the addition of retailers to a private

credit bureau database. At the time of writing, the deposit requirement for lending to small- and medium-sized

enterprises (SMEs) was 0%. The central banks training institute works with banks to build capacity for lending

to small rms, and the Bedaya Center of the General Authority for Investment is working to develop SMEs in

Egypt.

The banking sector is struggling with both fragmentation and a lack of competition between institutions. Eorts

to privatise state-owned banks have stalled owing to the nancial crisis and subsequently the revolution. As a

result, sizeable amounts of money are tied up in ineciently small institutions. To counteract further

fragmentation of the banking sector, the CBE has capped the number of operating licences for commercial

banks. Thus, acquisition of an existing bank is the only way to enter the sector. At the same time, however,

high yields and insucient access to nance, especially for smaller rms, suggest that competition between

banks for loan and investment opportunities is insucient. Allowing small banks with new business models

focusing on SMEs to enter the market without requiring a joint venture or purchase of an existing bank might

address these shortcomings.

Egypts stock market is lively and active, but its capitalisation is low compared to deposits in the banking

system. Market capitalisation was USD 71 billion before the revolution (end-June 2010) and had fallen by 4% to

about USD 64.8 billion as of October 2012

1

. The latter gure corresponds to 33% of total deposits in the

banking system, indicating the comparatively low importance of equity stocks.

Public Sector Management, Institutions & Reform

Revamping Egypts public sector to transform it from a post-socialist provider of large-scale employment with a

presence in most parts of the economy into a modern, ecient administration oriented towards service delivery

is among the most important and dicult challenges facing the government. Egypt has a large, inecient,

underpaid civil service subject to political pressure. In the long run, the size of the public administration is to be

restrained by replacing only those who retire. However, post-revolutionary governments have continued to use

the public sector as a tool to meet social pressure and demands for job creation, including increases in minimum

wages, making future reform even more difficult. Egypts public sector employs around 5.8 million persons, with

an additional 0.5 million temporary workers.

Egypt has more state-owned enterprises than the average for developing countries. Many of these public

entities are overstaed and underequipped, needing investment and sta reductions if they are to become

competitive. In addition, the Egyptian military holds a substantial share of state economic corporations, but little

is known about the extent or productivity of these holdings. Privatisation, which could transform these

companies, is hampered by the legacy of high-prole corruption cases in past (Mubarak-era) privatisation

projects. The new constitution explicitly makes it difficult to sell state assets.

Decentralisation could help make public sector management more ecient. A national strategy for

decentralisation, launched in July 2009, is based on ensuring the rights of local communities to decide on their

own needs and priorities. The nance ministry is developing a scal decentralisation plan, but in the meantime

local communities have no authority to raise revenue or create revenue sources on their own.

In enacting the new constitution, Egypt has taken the rst step in the arduous process of transforming its

political, social and economic institutional frameworks. Successful completion of the elections scheduled to begin

in April 2013 would be another step forward. In the future, it will be imperative for the government to work in

partnership with empowered civil society and private actors to build more accountable state institutions that

deliver efficient basic public services and enforce the rule of law.

Natural Resource Management & Environment

Egypt was ranked 60

th

out of 132 countries in the 2012 Environment Sustainability Index, a slight improvement

over the 2010 ranking of 68

th

out of 142 countries. With its numerous world cultural heritage sites and

renowned biodiversity hotspots, and given the economic importance of tourism, Egypt carefully conserves its

natural and cultural heritage.

Only 3.45% of Egypts land area is arable. The encroachment of urban areas into farmland, which has only

accelerated since the revolution, is therefore a worrisome trend. In the absence of eective land management,

farmland is being increasingly enclosed and divided up by urban sprawl, undermining productivity in the

agricultural sector. Climate change risks, including rising sea levels in the Nile Delta area, are another source of

concern.

Deteriorating water quality and decreasing quantity are major concerns. Population growth has reduced per

capita water use to less than 1 000 m

3

per year, while demand from households, agriculture and industry has

increased. This heightens the potential for conict with the Nile Basin riparian countries, as Egypts annual share

of Nile water resources remains fixed at 55.5 billion m

3

.

Egypts energy strategy, adopted in 2008, aims to increase the share of renewable energy sources to 20% by

2020. This increase will be obtained mainly by scaling up wind power to 12% (7 200 MW), as solar power

remains costly and internal hydropower capacity is nearly exhausted.

Collection of municipal solid waste covers only 65% of the 55 000 tonnes of waste that accumulate daily, posing

serious environmental challenges.

Political Context

In 2012, Egypt held its rst free parliamentary and presidential elections in more than 60 years, although the

parliamentary elections were later annulled by the Supreme Court and rescheduled for early 2013. Mohammed

Morsi of the Freedom and Justice Party (Muslim Brotherhood) was the victor of the presidential election. The

transition from a de facto military regime to a democratically legitimised one has been an important step. The

year closed in a less conciliatory tone with the adoption of a contested new constitution by referendum on

15 December 2012. The referendum was preceded by two weeks of sometimes violent protest by both

opposition and government supporters. The opposition considered that the constitution did not suciently

protect individual and religious freedoms.

The conict over the drafting of the constitution brought to the fore the rifts in the political landscape. The

initial anti-Mubarak coalition gave way to a strong opposition made up of liberal and conservative forces.

Considering the re-emergence of severe violence between protesters and government forces in January 2013,

the political camps seem bent on a strategy of confrontation. The 2013 parliamentary elections will mark an

important milestone and determine the new balance of power between, on one hand, the Muslim Brotherhood

and other Islamists, and on the other, the secular, liberal camps in the opposition.

Social Context & Human Development

Building Human Resources

By international standards, the government allocates a substantial amount of public spending to education (3.6%

of GDP and 12% of total spending in the 2012/13 budget), and universal primary education, one of the

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), has been achieved. Nonetheless, the existing system is arguably of low

quality and does not respond to the needs of the labour market: only two out of ten higher education graduates

nd jobs after graduation. Furthermore, the system exacerbates inequalities between the well-o, who can

aord access to high-quality education from private providers, and the poor, who cannot. The new constitution

commits the state to eradicating illiteracy (which currently affects 27% of the population) within ten years.

The 2012/13 budget allocates about 5.4% of total public expenditure (1.6% of GDP) to health. Despite an

extensive network of health facilities, there are urban-rural inequalities in access to health care. Egypts Health

Insurance Organisation covers only half the population, providing incentives for the growth of private sector

providers, which remain unregulated. HIV/AIDS prevalence among 15- to 49-year-olds is low about 0.03%

according to the World Health Organization, or 0.10% in 2009 according to the World Development

Indicators but there is a dearth of information on people living with HIV/AIDS.

High turnover in the civil service is slowing the change in social policies demanded by Egyptians. As a result,

poverty and unemployment rates remain high, and public service delivery in health and education remains

weak. To overcome these challenges, the government in March 2012 proposed an 18-month National Plan for

Priority Economic and Social Measures, the central objective of which is a New Social Contract that guarantees

higher social protection, better education and health services, and inclusive growth. Furthermore, to remove

constraints on public service delivery, the new constitution commits the state to provide improved health care

and education services, free of charge for those who are unable to pay, and guarantees sucient allocation of

public spending to these services.

Poverty Reduction, Social Protection & Labour

Egypt has made progress on human and social development and is on track to achieve the Millennium

Development Goals. Nevertheless, much remains to be improved and regional gaps are widening. The 2011

UNDP Human Development Index ranked Egypt 113

rd

out of 182 countries. Extreme poverty and hunger have

been curtailed; infant mortality and malnutrition have been halved; life expectancy has risen from 64 to 71

years; and there has been demonstrable improvement in maternal health and the ght against HIV/AIDS.

According to World Bank estimates, however, some 22% of Egyptians have incomes lower than USD 2 per day

per person, while rural poverty rates reach 44%. There are large regional disparities in income, infrastructure,

access to nance, education and labour markets. The rural-urban gap has been widening, with Cairo alone

producing over half of Egypts GDP. The World Bank estimates that Upper Egypt, with only 40% of the

population, accounts for 60% of poverty and 80% of the severely poor. Dependence on low-value agriculture

and disparities in the investment climate are major contributors to the rural-urban divide.

Egypt spent USD 22 billion (9% of GDP) during the 2011/12 scal year on social safety nets, mainly for subsidies

on energy (USD 16 billion, 6% of GDP) and food (USD 5 billion, 2% of GDP). These expenditure items have

been relatively constant over several decades. While social safety nets could make a measurable dierence to

the poor, less than 25% of Egypts subsidies actually reach their intended targets, while the subsidy system

contributes to unsustainable scal decits. Distribution mechanisms are untargeted and disproportionate across

regions. As a result, the top 40% of the population enjoys about 60% of energy subsidies, leaving the bottom

40% with only 25% of the benets. These disparities are wider in urban areas: the top 40% of the urban

population receives about 75% of energy subsidies and over 90% of petrol subsidies. The government has

initiated steps to reform the inecient energy subsidy system through the introduction of smart cards that

would cap the amount of petrol available to a consumer over a given period of time.

The situation of labour in post-revolutionary Egypt is uncertain. Since the revolution, strikes have become a

regular occurrence across sectors and regions. Although the government has taken sporadic measures to

address structural labour market problems, weak labour rights and standards remain a source of concern.

Unemployment protection schemes and social insurance laws protect only workers in the formal sector. The

governments minimum wage policy shows a lack of clarity and progress. In June 2011, Egypts interim

administration set the monthly wage rate for civil servants at USD 120 (EGP 700) per month. Some sources

suggest that this minimum rate will be raised to USD 200 (EGP 1 200) monthly within three years under

President Morsis Renaissance Project, yet even the implementation of the earlier rate of EGP 700 has proven

problematic: over half a million temporary workers in government have not received the promised minimum

wage, and it was unclear whether the minimum wage also applies to the private sector. If it had been fully

implemented in the civil service, the upward adjustment to the wage structure could have added

USD 1.5 billion to government spending in scal year 2011/12. The new constitution requires the government

to establish a minimum wage, a pension scheme, social insurance and health care that would guarantee decent

livelihoods for workers and in some cases the unemployed. Labour laws need to be strengthened in turn.

Gender Equality

In post-revolutionary Egypt, the economic and political empowerment of women is uncertain and their status

may be deteriorating. Womens participation in the democratic process remains challenged by the emerging

agenda of Islamist political forces. Recent political developments in the country demonstrate that it is dicult to

guarantee the enforcement of measures to promote gender equity in the current climate. Interim governments

after the revolution were criticised for not protecting womens rights, particularly concerning crimes against

women that occurred during the protests at Tahrir Square. Sexual harassment is a major concern and, given

Egypts international commitments, a liability. The National Council for Women is addressing this issue, but it

needs stronger political support.

Women remain marginalised in economic activities. Data from Egypts statistical agency show an unemployment

rate of 24% among women during the third quarter of 2012, more than double that of men (9.1%). Although

women make up 30% of the professional and technical workforce, only 9% of Egypts administrators and

managers were women in 2007.

Thematic analysis: Structural transformation and natural resources

Egypts economy is among the most diversied in Africa and does not depend on a single abundant natural

resource for future growth. Nevertheless, energy resources have played an increasingly important role over the

last decade relative to agriculture, manufacturing and services. Between 2000 and 2011, agriculture,

manufacturing and services each lost 2 to 3 percentage points of their contribution to Egypts GDP, whereas

extractive activities gained 7.6 percentage points. The weak performance of services is largely explained by the

sharp decline in tourism following the revolution. Financial services gained about 1 percentage point of GDP and

telecommunications doubled its contribution to 4%. Public administration gained 2 percentage points.

Structural reforms that opened the country up for investment and improved the business climate drove

economic expansion before the revolution. FDI reached USD 10 billion in 2006, up from USD 1 billion in 2000.

Investments largely went into oil and gas exploration and extraction, leading to a signicant expansion of

reserves, as well as into various service industries, especially tourism, nance and telecommunications. In

contrast, much of the manufacturing sector suered from trade liberalisation following Egypts accession to the

World Trade Organization in the late 1990s. The textile sector in particular suered heavily, as this largely

inecient state-owned sector began to face competition from cheaper imports, in both domestic and export

markets. Egypt has also managed to attract a signicant car manufacturing industry, but it produces largely for

the domestic market, which enjoys high import barriers.

Oil, natural gas and derivative products are the most important items in Egypts natural resource basket. Egypt

has also begun to mine and export gold, but so far only in small quantities. Extractive industries accounted for

15.6% of GDP in 2011/12. Exports of oil products and derivatives amounted to USD 13.5 billion in 2011/12,

accounting for just over half of all exports. Soft commodities come a far second, with USD 2.5 billion in

agricultural exports in 2010. The biggest line items are oranges (16% of exports in 2010), onions (7%) and

cotton (6%). Gas production has expanded signicantly over the last decade, thanks to foreign investment into

the sector. In 2011, gas production reached 2.17 trillion cubic feet (tcf), up from 0.74 tcf in 2000. According to

the Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company (EGAS), known reserves increased from 53 tcf in 2000 to 77 tcf in

2011 (quoted in Oxford Business Group). Yet-to-nd reserves that should be discovered by 2040 are estimated

at 90 tcf. Despite this strong growth, existing production capacity is insucient to meet both export and

domestic demand. As its export commitments to European and Asian markets are set in long-term contracts,

Egypt intends to build infrastructure for gas imports.

The oil sector presents a similar, if more mature, picture. Proven reserves increased from 3.7 billion barrels

(bbl) in 2010 to 4.4 billion barrels in 2012, due to exploration activity by international investors (Oil and Gas

Journal, January 2012 estimate). Despite these new nds, Egypts oil production has been in decline. The US

Energy Information Administration (EIA) reports that production in 2011 (727 000 bbl/day) was only 78% of its

1996 peak (EIA, International Energy Statistics). Domestic oil consumption, in contrast, has grown by over 30%

over the last decade and reached 815 000 bbl/d in 2011 (www.eia.gov/cabs/Egypt/Full.html), surpassing

production since 2008.

The puzzling contradictions of high and growing domestic demand, abundant natural resources and insucient

production are explained by articially distorted prices. Egypt has established a massive energy price subsidy

scheme that now carries the risk of undermining the very resource wealth whose benets it was meant to

spread. As a result of the subsidy, Egypts energy consumption is well above that found in comparable

economies and continues to grow much faster than elsewhere. Consumption of natural gas grew by 15% in

2011, a year of economic contraction. As world market prices for oil have risen, the governments losses from

providing cheap fuel to industry and households have become increasingly heavy, exceeding USD 1 billion per

year as of 2010 (Egypt Independent, www.egyptindependent.com/news/egypt-joins-list-mazut-importers). The

supply-side instrument of the energy pricing system is the monopsony of Egyptian Petroleum Corporation

(EGPC). Oil producers are required to sell their production to EGPC at a price below the world market price.

EGPC then feeds the crude oil into its reneries or sells it on international markets. Existing oil elds have

delivered sucient margins under this system, but these elds are maturing and newly discovered reserves are

increasingly dicult and expensive to access. As a result, investment in new production has been insucient, as

potential investors expect better returns. This situation is exacerbated by the current economic and political

uncertainty, which further deters investment.

Up the value chain, Egypt prides itself on having the largest petroleum rening sector in Africa. Rening crude

oil to higher-grade petroleum products is the rst step in the petroleum value chain and could be an important

stepping-stone to other higher value-added industries in the sector. Like most government-run industries in

Egypt, however, rening suers from underinvestment and outdated capital. Most of Egypts rening capacity is

at a low technological level and cannot meet domestic demand for rened petroleum products such as diesel

and fuel oil. An important improvement to the situation will be Egyptian Rening Corporation, the rst

internationally nanced (USD 3.7 billion) and privately run rening plant on a modern scale, which will supply

50% of Egypts diesel demand. Construction of the renery began in 2012. Given Egypts sizeable domestic

market for rened petroleum products, further upgrading of the rening sector through public-private

partnerships (PPPs) could ensure the sectors survival.

Egypt boasts substantial potential for both structural transformation towards more productive activities and for

making the most of its immense resource wealth. To achieve these goals, it must tackle two challenges. First,

liberalising the energy prices facing producers, reners, households and businesses would do much to bring

incentives back into line with the long-run objective of sustainable investment-driven growth. Second, attracting

much-needed investment to upgrade capital-intensive industries is crucial to making Egyptian industry

competitive. The biggest obstacles are the ossied market structures in these sectors, which are often

dominated by a few oligopolistic or monopolistic rms that are either government-owned or in the hands of

oligarchs following privatisation during the former regime.

Notes

1. The US dollar value of market capitalisation captures the eect of a lower exchange rate. As of early February

2013, the Egyptian pound had lost over 18% of its value compared to June 2010.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Fundamentals of Materials For Energy PDFDocument771 pagesFundamentals of Materials For Energy PDFws33% (3)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Load LetterDocument1 pageLoad LetterHutchings76No ratings yet

- A Guide To Calculating Your Boiler Emissions: A Step-By-Step Manual For Your ConvenienceDocument22 pagesA Guide To Calculating Your Boiler Emissions: A Step-By-Step Manual For Your ConvenienceRamon CardonaNo ratings yet

- AstraSR2018 CompressedDocument104 pagesAstraSR2018 CompressedShaniaNo ratings yet

- Rural ElectrificationDocument322 pagesRural ElectrificationArbaya's PageNo ratings yet

- Modificat de Art - Unic pct.8 DinDocument35 pagesModificat de Art - Unic pct.8 DinAndre' EaNo ratings yet

- MM 2014 Engleza PDFDocument7 pagesMM 2014 Engleza PDFAndre' EaNo ratings yet

- Marat NurgaliyevDocument37 pagesMarat NurgaliyevAndre' EaNo ratings yet

- S 2013 Egypt Agricultura EtcDocument28 pagesS 2013 Egypt Agricultura EtcAndre' EaNo ratings yet

- NaveleDocument1 pageNaveleAndre' EaNo ratings yet

- Its2013 eDocument208 pagesIts2013 eAndre' EaNo ratings yet

- 0 - Project 1 FINAL PDFDocument53 pages0 - Project 1 FINAL PDFShree ShaNo ratings yet

- Paper 19 Revised PDFDocument520 pagesPaper 19 Revised PDFAmey Mehta100% (1)

- Working Capital MGTDocument76 pagesWorking Capital MGTNSRanganathNo ratings yet

- MR Mansoor Islamabad ASU 160DVC QUOTATIONDocument12 pagesMR Mansoor Islamabad ASU 160DVC QUOTATIONMansoor Ul Hassan SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Ivan Resume 2017Document6 pagesIvan Resume 2017Sachi SinghNo ratings yet

- REC GST Registration Details25072017 PDFDocument1 pageREC GST Registration Details25072017 PDFJagadamba RealtorNo ratings yet

- 1.5-2wood Pellet Production LineDocument6 pages1.5-2wood Pellet Production LineddtyuriNo ratings yet

- Lock Out Tag Out: Review QuestionsDocument37 pagesLock Out Tag Out: Review QuestionsMansoor AliNo ratings yet

- GCC Petrochemical and Chemical Construction ProjectsDocument8 pagesGCC Petrochemical and Chemical Construction Projectslezz_coolNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Design of An Electric BikeDocument22 pagesConceptual Design of An Electric BikemehmetNo ratings yet

- 21200Document2 pages21200Talha TariqNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Plug - Finding Value in The Electric Vehicle Charging EcosystemDocument44 pagesBeyond The Plug - Finding Value in The Electric Vehicle Charging EcosystemAlfredo González NaranjoNo ratings yet

- CarrierDocument49 pagesCarrierJAMSHEER67% (3)

- FilmDocument2 pagesFilmDhileepan KumarasamyNo ratings yet

- Demand FactorDocument17 pagesDemand Factorkatiki216100% (1)

- Welspun Group Corporate PresentationDocument39 pagesWelspun Group Corporate PresentationAli SuhailNo ratings yet

- UL Low Voltage BuswayDocument56 pagesUL Low Voltage BuswaysicarionNo ratings yet

- Havells Sustainability Report 2012 13Document60 pagesHavells Sustainability Report 2012 13Karan Shoor100% (1)

- 4.1.9. Sektor Energetyczny W Polsce. Profil Sektorowy EN PDFDocument7 pages4.1.9. Sektor Energetyczny W Polsce. Profil Sektorowy EN PDFShubham KaklijNo ratings yet

- Duke Energy Fast FactsDocument2 pagesDuke Energy Fast FactsetggrelayNo ratings yet

- GE Steam Bypass System Ger4201Document18 pagesGE Steam Bypass System Ger4201Utku Kepcen100% (1)

- PL-230082 - Perenco Oil and Gas GabonDocument4 pagesPL-230082 - Perenco Oil and Gas GabonAdolfusNo ratings yet

- Poster 'I Want To Be ' - Rev0Document4 pagesPoster 'I Want To Be ' - Rev0hafizahmad84No ratings yet

- Thermal Power StationDocument18 pagesThermal Power Stationkamal_rohilla_1No ratings yet