Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Victor Bout

Uploaded by

dadplatinumCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Victor Bout

Uploaded by

dadplatinumCopyright:

Available Formats

November

|

December 2006 39

I

n many ways, Viktor Bout is a prototypical,

modern-day, multinational entrepreneur. He

is smart, savvy, and ambitious. Hes good

with numbers, speaks several languages, and

knows how to seize opportunities when they arise.

According to those whove met him, hes polite, pro-

fessional, and unassuming. Bout has no known his-

tory of violence, and no political agenda. He loves his

family. Hes fed the poor. And through his hard work,

hes become extraordinarily wealthy. During the past

decade, Bouts business acumen has earned him hun-

dreds of millions of dollars. What, exactly, does he do?

Former colleagues describe him as a postman, able to

deliver any package virtually anywhere in the world.

Not yet 40 years old, the Russian national also

happens to be the worlds most notorious arms

trafficker. He, more than almost anyone else, has

succeeded in exploiting the anarchy of globalization

to get goodsusually illicit goodsto market. Hes

a wanted man, desired by those who require a small

military arsenal and pursued by law enforcement

agencies who want to bring him down. Globe-trotting

weapons merchants have long flooded the Third

World with AK-47s, rocket-propelled grenades, and

warehouses of bullets and landmines. But unlike his

rivals, who tend to carve out small regional territories,

Bouts planes have dropped off his tell-tale military-

green crates from jungle landing strips in the Congo

to bleak hillside runways in Afghanistan. He has

developed a worldwide network of logistics, maneu-

vering through a maze of brokers, transportation

companies, financiers, and weapons manufacturers

both illicit and legitimateto deliver everything from

fresh-cut flowers, frozen poultry, and U.N. peace-

keepers to assault rifles and surface-to-air missiles

across four continents.

His client list for weapons is long. In the 1990s,

Bout was a friend and supplier to the legendary Ahmed

Shah Massoud, leader of the Northern Alliance in

Afghanistan, while simultaneously selling weapons

and aircraft to the Taliban, Massouds enemy. His

fleet flew for the government of Angola, as well as for

the unita rebels seeking to overthrow it. He sent an

aircraft to rescue Mobutu Sese Seko, the ailing and cor-

Russian entrepreneur Viktor Bout has made millions as the worlds most

efficient postman, able to deliver any kind of cargoespecially illicit

weaponsanywhere in the world. How was he able to build his

intricate underground network? By exploiting cracks in the anarchy of

globalization.

|

By Douglas Farah and Stephen Braun

Douglas Farah, a former Washington Post foreign corre-

spondent, is a terror finance consultant and author of Blood

from Stones: The Secret Financial Network of Terror (New

York: Broadway Books, 2004). Stephen Braun is a national

correspondent for the Los Angeles Times. The authors are

writing a book about Viktor Bout, which will be published

in 2007. I

L

L

U

S

T

R

A

T

I

O

N

B

Y

R

O

B

D

A

Y

F

O

R

F

P

The

Merchant

of

death

40 Forei gn Poli cy

[

The Merchant of Death

]

rupt ruler of Zaire, even though he had supplied the

rebels who were closing in on Mobutus last strong-

hold. He has catered to Charles Taylor of Liberia, the

Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, and Libyan

strongman Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi.

Bouts customers are not exclusively corrupt Third-

World leaders. He built his fortune by flying tons of

legitimate cargo, too. These included countless trips for

the United Nations into the same areas where he sup-

plied the weapons that sparked the humanitarian

crises in the first place. Hes done business with West-

ern governments, including the United States. Over the

past several years, the U.S. Treasury Department has

tried to put Bout out of business by freezing his assets

and imposing other sanctions on him, his business

associates, and his companies. But the Pentagon and

its contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan have simulta-

neously paid him millions of dollars to fly hundreds

of missions in support of post-war reconstruction in

both countries. In an age when the U.S. president has

divided the world into those who are with the United

States and those who are against it, Bout is both.

International officials believe that Bouts business

practicesin particular, his refusal to discriminate

among those who are willing to pay the right price

are, in fact, illegal. Peter Hain, then the British For-

eign Office minister responsible for Africa, stood in

Parliament in 2000 to lash out against those violat-

ing U.N. arms sanctions. He singled out Bout, dub-

bing him Africas merchant of death. But Bouts

deals often fall into a legal gray area that global

jurisprudence has simply failed to proscribe. Its not

for lack of trying. His peripatetic aircraft appear in

little-noticed U.N. reports documenting arms embar-

go violations in Liberia, the Democratic Republic of

the Congo, Angola, and Sierra Leone. U.S. spy satel-

lites have photographed his airplanes loading crates

of weapons on remote airstrips in Africa. American

and British intelligence officials have eavesdropped on

his telephone conversations. Interpol has issued a

red notice, requesting his arrest on Belgian weapons

trafficking and money-laundering charges.

Yet Bout has managed to elude authorities over and

over again. Laws simply do not address transnational,

nonstate actors such as Bout. His most egregious ille-

gal acts have included multiple violations of U.N. arms

embargos, a crime for which there is no penalty and for

which there is no enforcement mechanism. Today,

Bout lives openly in Moscow, protected by a Russian

government unconcerned by the international outcry

that surrounds him and his business empire.

I NTERNATI ONAL MAN OF MYS TERY

Much of Viktor Bouts early history is either

unknown or of his own making. He is married and

has at least one daughter; that much is true. His

older brother Sergei works for him. But any other

personal information is clouded in mystery. Even

his place of birth is unclear. According to his offi-

cial Russian passport, Bout was born on Jan. 13,

1967, in the faded Soviet outpost of Dushanbe,

Tajikistan. But during a 2002 radio interview in

Moscow, Bout said he was born near the Caspian

Sea in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan. A 2001 South

African intelligence report lists him as Ukrainian.

He is known to carry more than one passport and

use an array of aliases, including Vadim S. Aminov,

Victor Anatoliyevitsch Bout, Victor S. Bulakin,

and the sardonic favorite of his American pur-

suers, Victor Butt.

The deliberate obfuscation has made it diffi-

cult to track Bout, his partners, and his business. He

says he was an Air Force officer

and has acknowledged graduating

from the prestigious Soviet Mili-

tary Institute of Foreign Languages

in Moscow in the late 1980s. He

reportedly speaks fluent English,

French, Portuguese, Uzbek, and

several African languages. U.N.

officials say he worked as a trans-

lator for peacekeepers in Angola

in the late 1980s. Several reports tie him to Russ-

ian organized crime. Although British and South

African intelligence reports say that Bout was sta-

tioned in Rome with the kgb from 1985 to 1989,

he has strenuously denied any intelligence back-

ground. But military language school was a known

training ground for the gru (or Main Intelligence

Directorate)the vast, secretive, Soviet military

intelligence network that oversaw the Cold War

flow of Russian arms to revolutionary movements

and communist client states in the Third World.

Viktor Bout is a wanted man, desired by those who

require a small military arsenal and pursued by law

enforcement agencies who want to bring him down.

November

|

December 2006 41

Whether or not he was a secret agent, by the time

the Cold War ended, Bout had struck out on his own

and was ready to salvage the remaining scraps of the

Soviet empire. The entire Soviet Air Force was on life

support, as money for maintenance and fuel evap-

orated. Thousands of pilots and crew members were

suddenly unemployed. Hundreds of lumbering old

Antonov and Ilyushin cargo planes sat abandoned

at airports and military bases from St. Petersburg to

Vladivostok, their tires frayed and their worn frames

patched with sheet metal and duct tape.

Moving quickly, Bout acquired cargo planes des-

tined for the junkyard. By his own account, Bout,

then 25, bought his first trio of old Antonovs for

$120,000, hiring crews to fly cargo on a maiden

flight to Denmark, then on longer-distance routes to

Africa and the Middle East. But his business and

financial associates tell a different version. The

gru gave him three airplanes to start the business,

said one European associate who knew Bout in Rus-

sia and worked with him in Africa. He had finished

language school, but he had learned to fly. The

planes, countless numbers of them, were sitting

there doing nothing. They decided, lets make this

commercial. They gave Viktor the aircraft and in

exchange collected a part of the charter money.

Bouts initial stock in trade was the supply of guns

and ammunition abandoned in arsenals around the

former Soviet bloc. Many had airstrips built inside their

compounds, making loading easy. Guards were often

unpaid and their commanders were willing to sell the

weapons for a fraction of the market value. This avail-

ability of weapons was married to an instant clientele

of former Soviet clients, unstable governments, dicta-

tors, warlords, and guerilla armies clamoring for

steady supplies across Africa, Asia, and Latin Ameri-

ca. He had a logistics network, the best in the world,

says Lee S. Wolosky, a former staff member at the

National Security Council (nsc) who led the United

States interagency efforts to track Bout in the late

1990s. There are a lot of people who can deliver arms

to Africa or Afghanistan, but you can count on one

hand those who can deliver major weapons systems

rapidly. Viktor Bout is at the top of that list.

By the late 1990s, Bout had perfected his modus

operandithe ability to move his aircraft ahead of gov-

ernment efforts to ground them. To obtain permission

to fly internationally, an aircraft must be registered in

a country where its maintenance records and airwor-

thiness are certified. Each country in the world has a

series of call letters assigned to it, so the country of ori-

gin of any aircraft should be immediately identifiable

by matching call letters on a planes tail. By repeated-

ly registering planes in different countries, Bouts air-

craft were able to avoid local aviation rules, inspec-

tions, and oversight. According to a December 2000

U.N. investigation, Bout often registered his planes in

Liberia, a nation that had sold its aircraft registry to

Up in arms: One of the only known photographs of Viktor Bout, left, was taken with a zoom lens in central Africa.

C

O

U

R

T

E

S

Y

O

F

W

I

M

V

A

N

C

A

P

P

E

L

L

E

N

42 Forei gn Poli cy

business associates who helped Bout set up the avia-

tion and holding companies he used for arms traf-

ficking. Run from Kent, England, the Liberian Air-

craft Registration Bureau offered a full range of

services, without anyone ever inspecting the air-

craft. This included the creation of a company

name; air operators certificate (no restrictions); full

aircraft/company documentation; ferry permits and

crew validations, the U.N. report noted. That same

group controlled the registry of Equatorial Guinea,

so when international pressure mounted on Liberia

to decertify Bouts aircraft, he simply reregistered

them, a process that took only a few hours through

a series of phone and computer transactions.

Although Bouts aircraft were registered and rereg-

istered in far-flung corners of the world, they almost

all operated out of Sharjah, a small desert sheikdom

in the United Arab Emirates (uae) that serves as a cen-

tral base for flights to and from the former Soviet bloc,

the Middle East, Central Asia, and Africa. There,

Bout continued to muddle his company structures.

The aircraft registered in Equatorial Guinea operat-

ed under the name Air Cess, and those registered in

the Central African Republic flew for Central African

Airlines. Although the two airlines had different

addresses, they had the same Sharjah phone numbers.

Bouts first known weapons flights were to

Afghanistans Northern Alliance in 1992. Three

years later, a MiG fighter jet, flown by the Taliban,

intercepted a hulking freighter leased by Bout for

delivery of several million rounds of ammunition

to the government in Kabul. Taliban soldiers seized

the aircrafts cargo and imprisoned its crew. Bout

negotiated with the mullahs for months. Finally,

after a year, the crew pulled off what appeared to

be a miraculous escape, outwitting their captors by

flying the Ilyushin out of Kandahar. But skeptical

Western intelligence officials and Bouts rivals later

suggested the crews release was tied to Bouts

secret work for the mullahs. After all, in 1995,

Sharjah had established a free trade zone that soon

became known for its lax oversight and close ties

to Islamist radicals. Because the uae was one of

only three countries (along with Pakistan and Saudi

Arabia) to recognize the Taliban government in

Afghanistan, Sharjah became the main shopping

center for the regime, where it was able to purchase

everything from weapons and satellite telephones

to refrigerators and generators.

Soon a covert business relationship was estab-

lished between the Taliban and Bouts network. Bouts

avionics and maintenance crews serviced planes flown

by Ariana Afghan Airways, the national carrier then

controlled by the mullahs. Starting in 1998, accord-

ing to aircraft registration documents found in Kabul

by Afghan officials, Bouts operation and allied air

firms based in Sharjah sold the Taliban military a fleet

of cargo planes that was used to haul tons of arms and

material into Afghanistan. U.S. officials concluded that

the planes also ferried militant operatives, narcotics,

and cash. It was a lucrative venture. Western officials

estimate the Taliban paid Bout more than $50 million

during the years it ruled Afghanistan.

BOMBS AND RI CE

While developing his ties with the Taliban, Bout was

also perfecting his sanctions-busting business to the

south. Throughout the 1990s, his aging fleet was I

L

L

U

S

T

R

A

T

I

O

N

B

Y

K

E

V

I

N

H

A

N

D

F

O

R

F

P

crisscrossing Africa with weapons for all sides of

some of the continents most gruesome conflicts.

[There was] Sierra Leone and Liberia, a real bleed-

out across West Africa, recalls Gayle Smith, who

was senior director for African Affairs at the nsc at

the time. The Congo and Angola were still unre-

solved. And Sudan was heating up. Any one of these

conflicts would have been all-consuming by itself. But

they were happening all at once, and Bout was a com-

mon denominator.

U.N. investigators uncovered a small slice of his

activities in Angola. From July 1997 to October

1998, Bouts airplanes flew 37 flights from Burgas,

Bulgaria, to Lom, Togo, with weapons destined for

the unita rebels in Angola. The cargo included

20,000 82-mm mortar bombs, 6,300 antitank rock-

ets, 790 AK-47s, 1,000 rocket launchers, and 15

million rounds of ammunition. The total value of the

shipments was estimated at $14 million.

Bouts real money came when he realized he

could fly lucrative commercial cargo on the flights

back from the weapons deliveries. His most prof-

itable enterprise was flying gladiolas purchased for

$2 in Johannesburg and resold for $100 in Dubai.

Ever on the lookout for a good business oppor-

tunity, Bout even took part in humanitarian oper-

ations. In 1993, he flew Belgian peacekeepers to

Somalia as part of Operation Restore Hope,

using TransAvia Export Cargo Company, one of

his first ventures. A year later, his aircraft flew

2,500 French troops into Rwanda to help slow the

ethnic slaughter there. In 2000, he transported

hostage negotiators to the Philippines, where Euro-

pean tourists were being held by the terrorist group

Abu Sayyaf. He also frequently carried relief supplies

from the World Food Programme to impoverished

areas in Africa. And in the wake of the massive

Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004, his planes delivered

humanitarian goods and services to Sri Lanka.

THE HUNT FOR VI KTOR BOUT

Ironically, it was Bouts humanitarian flights

delivering European aid that eventually led

authorities to his illicit activities. Bout decid-

ed to expand his network northward in

1995, setting up several airfreight opera-

tions in Ostend, Belgium, where Belgian

intelligence began investigating him for pos-

sible gunrunning. Meanwhile, the cia was

picking up the first reports of his activities

in the Great Lakes region of East Africa.

And British intelligence officials in Sierra Leone,

worried about how their growing peacekeeping

force there would contend with the countrys steady

weapons flow, quietly set their sights on him, too.

The difference between Bout and the others was

that Bout was an integrated operation, says Johan

Peleman, a Belgian researcher who was hired by

the United Nations to help investigate Bout. He can

source the arms, he organizes the transport, and he

can source the financing. His genius was his abil-

ity to provide a door-to-door operation from the

arsenal to the buyer.

By the late 1990s, Bout had emerged as the per-

sonification of the new transnational threata high-

ly mobile global enabler, skilled at leveraging his

November

|

December 2006 43

assets and loyal to no country, deftly operating in

several continents and shrugging off international

standards. The U.S. government, in particular, grew

frustrated by the limitations of international law.

After all, domestic laws could not extend to Bouts

foreign arms deliveries. To apply pressure, U.S. offi-

cials turned to South Africa, where some of Bouts

planes had been based, and to Belgium, where police

had targeted his companies as part of a wide-rang-

ing money-laundering investigation. But despite

high-level requests, South African officials declined

to prosecute Bout due to lack of evidence, and the

Belgians and Americans failed to find common

ground on how to build a case.

Finally, in February 2002, the Belgian government

issued an international arrest warrant for Bout, charg-

ing him with laundering $325 million between 1994

and 2001. But by then, Bout was safe in Moscow.

Asked if Bout was in the country when the arrest

warrant was issued, the Russian foreign ministry said

no, even though Bout was giving live radio interviews

from studios in downtown Moscow. The next day, offi-

cials grudgingly acknowledged he might be in Russia

but said they had seen no evidence that he had com-

mitted any crime, and therefore could not act.

FLYI NG UNDER THE RADAR

Any momentum to scuttle Bouts business empire

quickly fizzled in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist

attacks. The Bush administration was almost imme-

diately preoccupied by its invasion of Afghanistan

and its wider war on terror. In April 2003, soon

after the United States invaded Iraq, American offi-

cials began laying the groundwork for a massive

commercial airlift. The U.S. military and the thou-

sands of private contractors hired to restore Iraqs

shattered infrastructure needed supplies for their

mission. By the summer, Antonovs were roaring into

Baghdads cratered airport, ferrying everything from

tents and video players to armored cars and refur-

bished Kalashnikovs.

But to their embarrassment, U.S. officials later

learned that many of the Russian planes were operated

by companies and crews working for Viktor Bout. His

planes were flying Federal Express shipments for the

U.S. Air Force, tents for the U.S. Army, and oil field

equipment and personnel for kbr, a Halliburton sub-

sidiary. In the months that followed, Bouts flagship

firm flew hundreds of sorties in and out of Baghdad,

earning millions of dollars from U.S. taxpayers.

How Bouts empire forged its secret U.S. con-

tacts is unclear. But, as U.S. intelligence and mil-

itary officials believe, the reason may be as simple

as Bout having the foresight to position his aircraft

in the region. He was able to make his services

available in the massive confusion that surround-

ed the supply operation, when no one had time to

check the credentials of the many air operations

vying for contracts.

As Bouts contracts became public, and the pos-

sible legal implications of continuing to deal with

him were explained by the U.S. Trea-

sury Department, the military

lurched toward a response. Air Force

officials reacted quickly, revoking

the fuel allowance and persuading

Federal Express to sever its contract.

But the U.S. Army and other defense

agencies insisted they had no respon-

sibility to scrutinize second-tier sub-

contractors. Bouts flights for kbr

continued well into late 2005, and even expanded to

include flights into Bagram Airfield in Afghanistan.

Several well-known Bout firms were finally banned

from Iraq early this year by military officials. But

Bout was suspected of shifting his operations to new

firms, and U.S. officials fear that those companies may

try to land lucrative U.S. contracts again.

On April 26, 2005, then Assistant Treasury Sec-

retary for Terrorist Financing Juan Zarate announced

new U.S. economic sanctions against 30 companies in

Bouts financial orbit. Although Bout was not desig-

nated as a terrorist himself, Zarate noted that he had

profited from supplying the Taliban with military

equipment when it ruled Afghanistana relation-

ship that connected Bout, at least indirectly, to Osama

bin Laden and al Qaeda. Therefore, U.S. entities were

now banned from doing business with any of Bouts

companies, even indirectly. Eight months later, the U.S.

list was adopted by the full U.N. Security Councils

Liberia committeea move not impeded by the Russ-

ian delegation. In theory, the international sanctions

should have put an end to Bouts trafficking.

44 Forei gn Poli cy

[

The Merchant of Death

]

Bout has said that he did not knownor did he

have any obligation to knowthe contents of the

long, green crates he ferried into war zones.

November

|

December 2006 45

Yet investigators have discovered several newly

formed Bout enterprises operating aircraft that are

still registered to Air Cess and other companies.

Human rights monitors have heard that his planes

flew into the northern part of the Democratic Repub-

lic of the Congo this year. And in January, one of

Bouts carriers, Irbis Air Company, bid on a contract

with Halliburton in Iraq. Despite the uaes assur-

ances that it has grounded his fleet, Bout often

exploits the fact that U.S. military air controllers on

duty in Sharjah, who control traffic into Iraq, rotate

jobs every six months. His businessesincluding

new shell companies registered in Moldova and

elsewhere in Eastern Europeapply for contracts

before the new person has time to find out who is

designated or what to watch for. It is a constant

I

f Viktor Bouts empire were put out of business, the flow of

weapons to the worlds trouble spots would not grind to a halt.

But it is unlikely that a similar networka large, vertically

structured organization capable of door-to-door delivery of

advanced weapons and hardwarewould emerge in its place.

Instead, the world of arms trafficking would return to the way

it was during the Cold War. No single weapons broker could offer

the full range of services that Bout does. There are several rea-

sons why. For starters, the world is more aware of transnation-

al threats today, and a new Bout would likely be spotted and

stopped earlier in his career. Although Russia is still awash in

weapons and aircrafts, it is no longer the Wild West it was when

Bout staked his claim in the early 1990s. Many areas of Africa

are now so saturated with weapons (many of which were pro-

vided by Bout) that their value has dropped markedly. For exam-

ple, the price of an AK-47 in the Niger Delta region has dropped

from $250 to $75 in the past 18 months.

Future operators will likely have to create business models

with more middlemen and fewer profits. The more steps there are

between acquiring weapons and transporting them, the more

opportunities there are for law enforcement or intelligence agen-

cies to break up international weapons cartels. If the

profitability of the weapons trade diminishesin part

because of the success of traffickers such as Bout in

meeting the market demandtransporting weapons will

be just one of several portfolios for illicit air merchants.

Like Bout, future gunrunners will probably have to

rely on both legal and illegal cargoes. There is a severe

airlift capacity deficit across the world, making owner-

ship of aircraft as valuable as the weapons they carry.

That means legitimate business should be economically

viable and more competitive with illegal cargoes, though

it will not do away with illicit transport networks. The

transportation of valuable commodities such as dia-

monds, coltan, and timber will likely remain lucrative.

Nowhere will that prove more true than in Africa, where

corruption is endemic, the need to skirt the law for

personal profit remains high, and the viability of truly legitimate

operations is precarious.

That is not to say the weapons business will disappear; there

are already people positioned to keep the arms pipeline moving. The

leading arms smugglers of the future are likely to include some of

Bouts former business partners. One such person is Sanjivan

Ruprah, who allegedly helped Bout broker several major weapons

deals for Liberias former dictator Charles Taylor and arms for

Sierra Leones Revolutionary United Front. The 40-year-old Kenyan

national is on the United Nations asset freeze list and travel ban

for those deals. He was arrested twice (once in Belgium in Febru-

ary 2002 and then in Italy that August), but he skipped bail both

times. Ruprah is currently at large (and back in business) in Africa.

He is only one of the many arms traffickers who would try to

pick up where Bout left off. Dozens more are waiting in the wings.

But none will have the clout or reach of Viktor Bout. On their best

days, [other arms dealers] couldnt influence a war either way. They

were peanuts, says one U.S. official who asked not to be identi-

fied because of ongoing investigations of Bout. Bout could make

or break a country. It may be some time before we see the likes

of him again. DF

What would the global flow of weapons look like without Viktor Bout? Dozens of traffickers wait in the wings.

Arms Around the World

J

E

H

A

D

N

G

A

/

C

O

R

B

I

S

Shell game: If Bout were gone, other traffickers would pick up the pieces.

fight, because the military wants to fly stuff and

the new people are under pressure, and tracking

aircraft ownership is, frankly, not a priority, said

a U.S. official involved in the Bout hunt.

Conceding their difficult straits, U.S. officials

admit that there is no clear evidence that Bouts air

fleet has been diminished or his activities slackened

as a result of the sanctions. You never can say with

100 percent certainty that he is gone, says

Zaratewho is now President George W. Bushs

chief counterterror deputy at the nsc. He is very,

very good at doing his business. The Europeans

find it equally hard. He doesnt go away. He just

keeps changing his aircraft and registrations, hop-

ing that he will outlast the interest in following

him, says a European military intelligence source.

So far, he is right.

THE S I EVE OF GLOBALI ZATI ON

Today, international efforts to pursue Bout have large-

ly been abandoned. The cia no longer has personnel

specifically tasked with following his activities. The Bel-

gian money-laundering investigation has stalled over

internal feuding and lack of government interest. Only

the British maintain an active intelligence effort to

track him, and even that effort is greatly reduced.

In the meantime, Bout lives in a luxury apartment

complex in Moscow, where he is occasionally spotted

eating out at fancy sushi bars. Richard Chichakli,

Bouts American business partner, also moved to

Russia, using frequent flier miles to buy a ticket out

of Texas after his assets were frozen in April 2005

by U.S. officials, who suspected he was running

some of Bouts businesses from the United States. In

theory, neither of them is allowed to go abroad

because of a U.N. travel ban. But U.S. officials

involved in the Bout hunt say there were credible

Bout sightings earlier this year in Beirut. Mean-

while, the Russian government declines to answer

any questions about Bout, who reportedly has cul-

tivated close ties with senior military and other

government officials in Moscow.

Bout himself has said that he did not knownor

did he have any legal or ethical obligation to

knowthe contents of the long, green crates he

ferried into war zones. Strict economic calcula-

tions, not ideology, have been the guiding star of

Bouts operations. But what motivates a man to

shove such moral implications aside? Is it the quest

for wealth? The adrenaline rush of operating in

dangerous circumstances? The knowledge that some

of the worlds most powerful people rely on you?

No one else would deliver the packages, says

46 Forei gn Poli cy

[

The Merchant of Death

]

F

A

I

S

A

L

M

A

H

M

O

O

D

/

R

E

U

T

E

R

S

A force for good and evil: Relief supplies for tsunami survivors are loaded onto one of Bouts planes in Pakistan.

November

|

December 2006 47

one of Bouts South African associates. You never

shoot the postman.

Perhaps the existence of the merchant of death

says more about the world today than it does about

the man himself. The halting efforts to disrupt his

activities tell a chastening story of the failure of

nations. Indeed, Viktor Bout is a product of the

convergence of history and opportunity, an entre-

preneur who saw a chance to turn an incredible

profit in a rapidly changing world. In the Cold

War, each side was able to enforce adherence to ide-

ological imperatives by controlling the supply and

demand of just about everything. When the Berlin

Wall came down, so did the controls, and the mar-

ket was thrown open to those who could seize the

moment. Bout grasped that his services could be

useful to any party desperately seeking the weapons

he could provide. With a growing number of failed

and failing states dependent on inexpensive and

readily available weapons, Bout was able to craft

a transglobal network to meet this market. If you

look at all of Bouts various escapades, how easy

it was for him to move weapons, get end-user cer-

tificates, and change aircraft registration, says

Michael Chandler, a retired British colonel who led

a U.N. panel on the Taliban and al Qaeda, you get

an amazing picture of how corrupt many parts of

the world are.

Even in todays new world order, where the Unit-

ed States is the sole superpower and old ideologies are

diminished, governments have yet to come to grips

with the emergence of transnational criminal groups.

These armed, nonstate actors disregard borders,

dispassionately working with the Taliban and the

U.S. military and other unlikely bedfellows, breed-

ing instability and violence for personal profit, not

ideology. Traffickers like Bout invented new rules as

they went along. Rather than being impediments to

the flow of weapons, arms embargos simply allowed

them to jack up prices. International name and

shame campaigns, with no enforcement ability,

served only to advertise their services.

Many arms control experts say that if Bouts

empire were finally brought to heel, the interna-

tional weapons business would simply fragment into

smaller fiefdoms, similar to the way that the Colom-

bian Cali and Medelln cocaine cartels dissembled in

the 1990s after their leaders were killed. What they

fail to mention, though, is that the net production of

cocaine did not diminish, and the shrunken, tight-knit

cartels proved equally difficult to dismantle. Indeed,

in todays world, any attempt to halt illicit activities

whether its trafficking by Viktor Bout or by some-

one elsecan truly be read as the second labor of

Hercules. Whenever the hydras head is cut off, two

more grow in its place.

Journalist Peter Landesman scored a rare interview with Viktor Bout for his profile of the notorious

trafficker in Arms and the Man (The New York Times Magazine, Aug. 17, 2003).

For information about the rise of weapons dealers and their operations, read The Arms Fixers: Con-

trolling the Brokers and Shipping Agents (Washington: basic Publications, 1999) a report by arms

trafficking experts Brian Wood and Johan Peleman. The International Consortium of Investigative Jour-

nalists spent years scouring intelligence reports, government documents, court records, and other

public documents for its book about post-Cold War illicit economies, Making a Killing: The Business

of War (Washington: Center for Public Integrity, 2003). Foreign PolicyEditor in Chief Moiss Nam

examines illegal trade in the global economy in his book Illicit: How Smugglers, Traffickers and Copy-

cats are Hijacking the Global Economy (New York: Random House, 2005).

In May 2002, pbs produced a documentary called Gunrunners for its show Frontline. The film

features several weapons smugglers, including Viktor Bout, and can be accessed online at pbss Web

site. For Hollywoods take on the world of arms trafficking, watch the 2005 movie Lord of War, star-

ring Nicolas Cage, a fictional account partially based on Bouts imagined life.

For links to relevant Web sites, access to the FP Archive, and a comprehensive index of related

Foreign Policy articles, go to www.ForeignPolicy.com.

[

Want t o Know More?

]

You might also like

- South Africa and United Nations Peacekeeping Offensive Operations: Conceptual ModelsFrom EverandSouth Africa and United Nations Peacekeeping Offensive Operations: Conceptual ModelsNo ratings yet

- Urban Warefare Case StudiesDocument52 pagesUrban Warefare Case StudiesswdgeldenhuysNo ratings yet

- Patton Vs GuderianDocument25 pagesPatton Vs GuderianGreg JacksonNo ratings yet

- Morgan Richard Tsvangirai's Legacy: Opposition Politics and the Struggle for Human Rights, Democracy and Gender SensitivitiesFrom EverandMorgan Richard Tsvangirai's Legacy: Opposition Politics and the Struggle for Human Rights, Democracy and Gender SensitivitiesNo ratings yet

- 1940-44 Insurgency in ChechnyaDocument4 pages1940-44 Insurgency in ChechnyaAndrea MatteuzziNo ratings yet

- What Lies Across the Water: The Real Story of the Cuban FiveFrom EverandWhat Lies Across the Water: The Real Story of the Cuban FiveNo ratings yet

- The Mansur NetworkDocument4 pagesThe Mansur NetworkRobin Kirkpatrick BarnettNo ratings yet

- Congo 20021031Document59 pagesCongo 20021031Leon KukkukNo ratings yet

- Hard Cases – True Stories of Irish Crime: Profiling Ireland's Murderers, Kidnappers and ThugsFrom EverandHard Cases – True Stories of Irish Crime: Profiling Ireland's Murderers, Kidnappers and ThugsNo ratings yet

- 2000-07-01 Grozny 2000 - Urban Combat Lessons Learned (Thomas)Document14 pages2000-07-01 Grozny 2000 - Urban Combat Lessons Learned (Thomas)Claudiu Ionut RusuNo ratings yet

- Taliban and Their Manifesto: Assignment TopicDocument9 pagesTaliban and Their Manifesto: Assignment TopicZuHaJamEelNo ratings yet

- Spies and Secret Service - The Story of Espionage, Its Main Systems and Chief ExponentsFrom EverandSpies and Secret Service - The Story of Espionage, Its Main Systems and Chief ExponentsNo ratings yet

- Tactical Observations From The Grozny Combat ExperienceDocument127 pagesTactical Observations From The Grozny Combat ExperienceMarco TulioNo ratings yet

- Imaginary Crimes: The Never Ending Viktor Bout StoryDocument15 pagesImaginary Crimes: The Never Ending Viktor Bout StoryGeorge MappNo ratings yet

- We Were Blackwater: Life, death and madness in the killing fields of Iraq – an SAS veteran's explosive true storyFrom EverandWe Were Blackwater: Life, death and madness in the killing fields of Iraq – an SAS veteran's explosive true storyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 12 Baluch in 1971 WarDocument9 pages12 Baluch in 1971 WarStrategicus Publications100% (1)

- Operation Relentless Chapter ExtractDocument25 pagesOperation Relentless Chapter ExtractQuercus BooksNo ratings yet

- Deception in High Places: A History of Bribery in Britain's Arms TradeFrom EverandDeception in High Places: A History of Bribery in Britain's Arms TradeNo ratings yet

- After Nisman ReportDocument64 pagesAfter Nisman ReportEl EstímuloNo ratings yet

- The Soul of Boston and The Marathon BombingDocument271 pagesThe Soul of Boston and The Marathon BombingTony ThomasNo ratings yet

- Hunting Bin Laden: How Al-Qaeda is Winning the War on TerrorFrom EverandHunting Bin Laden: How Al-Qaeda is Winning the War on TerrorNo ratings yet

- Romeo SpyDocument247 pagesRomeo SpygichuraNo ratings yet

- Who Is Vladimir Putin?: Fiona HillDocument9 pagesWho Is Vladimir Putin?: Fiona HillZineil BlackwoodNo ratings yet

- Taking on Iran: Strength, Diplomacy, and the Iranian ThreatFrom EverandTaking on Iran: Strength, Diplomacy, and the Iranian ThreatNo ratings yet

- State Secret: PrefaceDocument47 pagesState Secret: PrefacebsimpichNo ratings yet

- Faces of Terrorism and The Ultimate Solution. By: Prit Paul Singh BambahFrom EverandFaces of Terrorism and The Ultimate Solution. By: Prit Paul Singh BambahNo ratings yet

- T4 B18 Saudi Connections Generally FDR - Entire Contents - Press Reports - 1st Pgs Scanned For Reference - Fair Use 688Document53 pagesT4 B18 Saudi Connections Generally FDR - Entire Contents - Press Reports - 1st Pgs Scanned For Reference - Fair Use 6889/11 Document ArchiveNo ratings yet

- Peculiar Liaisons in War Espionage and Terrorism in The Twentieth CenturyDocument264 pagesPeculiar Liaisons in War Espionage and Terrorism in The Twentieth CenturyKamahllegend67% (3)

- The Ideological-Political Training of Iran's BasijDocument10 pagesThe Ideological-Political Training of Iran's BasijCrown Center for Middle East StudiesNo ratings yet

- Kandahar Assassins: Stories from the Afghan-Soviet WarFrom EverandKandahar Assassins: Stories from the Afghan-Soviet WarNo ratings yet

- The Citys Many FacesDocument680 pagesThe Citys Many FacesusnulboberNo ratings yet

- Power Struggle Over Afghanistan: An Inside Look at What Went Wrong--and What We Can Do to Repair the DamageFrom EverandPower Struggle Over Afghanistan: An Inside Look at What Went Wrong--and What We Can Do to Repair the DamageRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Pakistan Army in KashmirDocument80 pagesPakistan Army in KashmirStrategicus PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Iran's Hollow VictoryDocument18 pagesIran's Hollow VictoryArielNo ratings yet

- British Governance Of The North-West Frontier (1919 To 1947): A Blueprint For Contemporary Afghanistan?From EverandBritish Governance Of The North-West Frontier (1919 To 1947): A Blueprint For Contemporary Afghanistan?No ratings yet

- Intelligence Failure or Design? Karkare, Kamte and The Campaign For 26/11 TruthDocument27 pagesIntelligence Failure or Design? Karkare, Kamte and The Campaign For 26/11 TruthSukumar MuralidharanNo ratings yet

- 6 Undercover ArmiesDocument598 pages6 Undercover ArmiesDanel GrigoriNo ratings yet

- The Prosperity Agenda: What the World Wants from America--and What We Need in ReturnFrom EverandThe Prosperity Agenda: What the World Wants from America--and What We Need in ReturnNo ratings yet

- Lebanon at Risk: Conflict in Bekaa ValleyDocument10 pagesLebanon at Risk: Conflict in Bekaa ValleyLinda LavenderNo ratings yet

- The Five FamiliesDocument52 pagesThe Five FamiliesjuliamagisterNo ratings yet

- Countergangs1971 76 PDFDocument37 pagesCountergangs1971 76 PDFClayton RobertsonNo ratings yet

- Our Eyes: Counter Terrorism Intelligence NetworkFrom EverandOur Eyes: Counter Terrorism Intelligence NetworkNo ratings yet

- Terror and Social MediaDocument112 pagesTerror and Social MediaAnonymous wZIExzg50% (2)

- Superstitious Beliefs of MaranaoDocument13 pagesSuperstitious Beliefs of MaranaoKhent Ives Acuno SudariaNo ratings yet

- A Life for a Life: A Memoir: My Career in Espionage Working for the Central Intelligence AgencyFrom EverandA Life for a Life: A Memoir: My Career in Espionage Working for the Central Intelligence AgencyNo ratings yet

- 2015 ACI Airport Economics Report - Preview - FINAL - WEB PDFDocument12 pages2015 ACI Airport Economics Report - Preview - FINAL - WEB PDFDoris Acheng0% (1)

- How To Write A Cover Letter For A Training ProgramDocument4 pagesHow To Write A Cover Letter For A Training Programgyv0vipinem3100% (2)

- Drama For Kids A Mini Unit On Emotions and Character F 2Document5 pagesDrama For Kids A Mini Unit On Emotions and Character F 2api-355762287No ratings yet

- Keyboard notes to Fur Elise melodyDocument2 pagesKeyboard notes to Fur Elise melodyReji SarsalejoNo ratings yet

- Electrical Power System Protection BookDocument2 pagesElectrical Power System Protection BookHimanshu Kumar SagarNo ratings yet

- DC Rebirth Reading Order 20180704Document43 pagesDC Rebirth Reading Order 20180704Michael MillerNo ratings yet

- RTS PMR Question Bank Chapter 2 2008Document7 pagesRTS PMR Question Bank Chapter 2 2008iwan93No ratings yet

- Mixed-Use Proposal Dormitory and Hotel High-RiseDocument14 pagesMixed-Use Proposal Dormitory and Hotel High-RiseShanaia BualNo ratings yet

- OutliningDocument17 pagesOutliningJohn Mark TabbadNo ratings yet

- PCC ConfigDocument345 pagesPCC ConfigVamsi SuriNo ratings yet

- Recommender Systems Research GuideDocument28 pagesRecommender Systems Research GuideSube Singh InsanNo ratings yet

- Bullish EngulfingDocument2 pagesBullish EngulfingHammad SaeediNo ratings yet

- RITL 2007 (Full Text)Document366 pagesRITL 2007 (Full Text)Institutul de Istorie și Teorie LiterarăNo ratings yet

- SubjectivityinArtHistoryandArt CriticismDocument12 pagesSubjectivityinArtHistoryandArt CriticismMohammad SalauddinNo ratings yet

- Chippernac: Vacuum Snout Attachment (Part Number 1901113)Document2 pagesChippernac: Vacuum Snout Attachment (Part Number 1901113)GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Design and Construction of Food PremisesDocument62 pagesDesign and Construction of Food PremisesAkhila MpNo ratings yet

- 3 CRIM LAW 2 CASES TO BE DIGESTED Gambling Malfeasance Misfeasance Bribery Graft Corruption and MalversationDocument130 pages3 CRIM LAW 2 CASES TO BE DIGESTED Gambling Malfeasance Misfeasance Bribery Graft Corruption and MalversationElma MalagionaNo ratings yet

- The Apostolic Church, Ghana English Assembly - Koforidua District Topic: Equipping The Saints For The MinistryDocument2 pagesThe Apostolic Church, Ghana English Assembly - Koforidua District Topic: Equipping The Saints For The MinistryOfosu AnimNo ratings yet

- Issues and Concerns Related To Assessment in MalaysianDocument22 pagesIssues and Concerns Related To Assessment in MalaysianHarrish ZainurinNo ratings yet

- Prof 7 - Capital Market SyllabusDocument10 pagesProf 7 - Capital Market SyllabusGo Ivanizerrckc100% (1)

- CLNC 2040 Reflection of Assistant ExperiencesDocument4 pagesCLNC 2040 Reflection of Assistant Experiencesapi-442131145No ratings yet

- NAS Drive User ManualDocument59 pagesNAS Drive User ManualCristian ScarlatNo ratings yet

- TAFJ-H2 InstallDocument11 pagesTAFJ-H2 InstallMrCHANTHANo ratings yet

- Accounting Notes - 1Document55 pagesAccounting Notes - 1Rahim MashaalNo ratings yet

- 2005 Australian Secondary Schools Rugby League ChampionshipsDocument14 pages2005 Australian Secondary Schools Rugby League ChampionshipsDaisy HuntlyNo ratings yet

- PERDEV - Lesson 3 ReadingsDocument6 pagesPERDEV - Lesson 3 ReadingsSofiaNo ratings yet

- APEC ArchitectDocument6 pagesAPEC Architectsarah joy CastromayorNo ratings yet

- The Magnificent 10 For Men by MrLocario-1Document31 pagesThe Magnificent 10 For Men by MrLocario-1Mauricio Cesar Molina Arteta100% (1)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

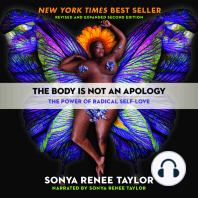

- The Body Is Not an Apology, Second Edition: The Power of Radical Self-LoveFrom EverandThe Body Is Not an Apology, Second Edition: The Power of Radical Self-LoveRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (365)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (44)

- Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldFrom EverandPrisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1143)

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndFrom EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndNo ratings yet

- If I Did It: Confessions of the KillerFrom EverandIf I Did It: Confessions of the KillerRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (132)

- Selling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansFrom EverandSelling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedFrom Everand1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (109)