Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Shakespeare in The Romanian Cultural Memory

Uploaded by

crisvodaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Shakespeare in The Romanian Cultural Memory

Uploaded by

crisvodaCopyright:

Available Formats

Shakespeare

in the Romanian

Cultural Memory

Monica Matei-Chesnoiu

Fairleigh Dickinson University Press

Shakespeare

in the Romanian

Cultural Memory

PAGE 1 ................. 11420$ $$FM 10-20-05 11:12:11 PS

This page intentionally left blank

Shakespeare

in the Romanian

Cultural Memory

Monica Matei-Chesnoiu

With a Foreword by Arthur F. Kinney

Madison Teaneck

Fairleigh Dickinson University Press

PAGE 3 ................. 11420$ $$FM 10-20-05 11:12:12 PS

2006 by Rosemont Publishing & Printing Corp.

All rights reserved. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use,

or the internal or personal use of specic clients, is granted by the copyright owner,

provided that a base fee of $10.00, plus eight cents per page, per copy is paid di-

rectly to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, Massachu-

setts 01923. [0-8386-4081-8/06 $10.00 8 pp, pc.]

Associated University Presses

2010 Eastpark Boulevard

Cranbury, NJ 08512

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American

National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials

Z39.48-1984.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Matei-Chesnoiu, Monica, 1954

Shakespeare in the Romanian cultural memory / Monica Matei-Chesnoiu ; with

a foreword by Arthur F. Kinney.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 0-8386-4081-8 (alk. paper)

1. Shakespeare, William, 15641616Translations into RomanianHistory and

criticism. 2. Shakespeare, William, 15641616Stage historyRomania.

3. Shakespeare, William, 15641616AppreciationRomania. 4. English

languageTranslating into Romanian. 5. Translating and interpreting

Romania. 6. TheaterRomania. I. Title.

PR2881.5.R6M38 2006

822.33dc22 2005014324

printed in the united states of america

PAGE 4 ................. 11420$ $$FM 10-20-05 11:12:12 PS

To my daughter, Joanna

PAGE 5 ................. 11420$ $$FM 10-20-05 11:12:12 PS

This page intentionally left blank

Contents

List of Illustrations 9

Foreword 11

Arthur F. Kinney

Acknowledgements 15

1. Mapping Shakespeares Globe in a Global World 19

2. Early Translations of Shakespeare in Romania 27

3. Shakespeares Decalogue: English Histories in Romania 67

4. Romanian Metamorphoses: Comedies 96

5. Shakespeare, Communism, and After: Tragedies 158

6. Staging Revenge and Power: Masks of Romanian Hamlets 194

7. Romanian Mental and Theatrical Maps: Romances 220

Notes 237

Bibliography 254

Index 266

PAGE 7

7

................. 11420$ CNTS 10-20-05 11:12:17 PS

This page intentionally left blank

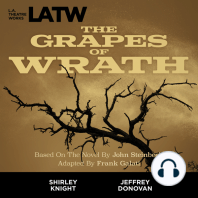

Illustrations

Richard III dircted by Ion S ahighian at the Nottara Theater

(1964). 76

Richard III directed by Horea Popescu at the Bucharest

National Theater (1976). 77

Twelfth Night directed by Anca Ovanez-Dorosenco at the

Bucharest National Theater (1984). 121

Twelfth Night (The Kings Night or What You Will ) directed by

Andrei S erban at the Bucharest National Theater (1991). 140

Hamlet directed by Vlad Mugur at the Cluj National Theater

(2001). 214

PAGE 9

9

................. 11420$ ILLU 10-20-05 11:12:22 PS

This page intentionally left blank

Foreword

Arthur F. Kinney

A catwalk traversed the stage; and lots of ropes hung from the state can-

opy, like lianas in a tropical forest. Like in a simple sentence, this setting

made a visible statement: the world was a jungle. This homo homini lupus

motto became an ad litteram declaration when the audiences could see

kings, princes, cardinals, and attendants hanging from these ropes like

monkeys, and jumping into the political world of the stage. As a theater

critic noticed about this production, had we lived during King Johns

reign, we would have felt avenged. This was an exceptionally daring

statement, because the critic clearly transposed the political situation

from British history to the contemporary Romania, regardless of the

Communist censorship.

MONICA MATEI-CHESNOIU IS DESCRIBING A PRODUCTION OF SHAKE-

speares King John at the Comedy Theater in Bucharest in 1988; and

she notes that the reviewer escaped without harm because the Com-

munist regime in Romania was already at the verge of collapse. But

it was anyones call at the moment. For her, the moral rectitude

and verticality of the play and this staging of it exposed the in-

credible heights of worldly ambition and political power. At the

end of the performance, a memorable ending created by pure

directorial invention, four of King Johns followers were left in ob-

scurity, sequestered by the higher conspiracy of history, vanishing

into the darkness of the stage.

This is only one of the countless memorable performances which

Matei-Chesnoiu records that illuminate what she calls a liminal

space at the cultural margin of Europe, . . . a place somewhere near

the Black Sea and the Danube, where Shakespeare has been per-

formed, translated, and interpreted successfully for almost two cen-

turies. The three provinces that constitute this marginthe

Romanian provinces of Wallachia, Moldova, and Transylvaniaare

the focus of this rich, substantial, and transformative study of the

potential meanings of Shakespeare and the political uses and social

purposes to which his plays have been put in our time. In the cur-

PAGE 11

11

................. 11420$ FRWD 10-20-05 11:12:24 PS

12 FOREWORD

rent critical climate, where cultural forces and performance theory

dominate our research and writing, this essentially groundbreaking

book expands our horizons, revealing to us in stark yet illuminating

detail just what Shakespeare has meant to Eastern Europe in the

dark days of World War II, its Communist aftermath, and, nally, its

liberationand how, throughout this time, it has managed to keep

a hold, however tenuous, on the Western world it has held up as

informant and paradigm.

For Matei-Chesnoiu, Romania remains an ineluctable site of cul-

tural memory which, like the ghost in Hamlet, seizes our attention

and will not let us go. She nds that Shakespearean performances

did vital and indestructible, if often indirect, cultural work because

Shakespearean performances were always interpretations negotiat-

ing the England of the 1500s and 1600s and the Romania of today

as well as the larger Eastern European network of countries. Geo-

graphically, she points out, many of the lands which we think of as

classical and which provided Shakespeare with substance, myth, and

metaphor were what we now know as East European soil, something

made clear in the maps of Ortelius circulating in the Tudor period.

Often exotic and eccentric facts and lands then were facts and lands

Romanians know all too well. Shakespeares utilization of them

indeed, his very interventiongives Romania a kind of just cause to

deploy his works metamorphosed through Fascist and Communist

regimes. Postwar Romanias view of Tudor England, she argues,

was seen as a passive form of resistance against the communist ide-

ology, and was one that, in time, the disintegrating regime was

propagating every more feebly.

The forces of history, dominated by the liberation of eastern Eu-

rope by the West, caused Communism to come to an end; but this

engrossing study suggests that Shakespeare too played a part. Early

on there was a need for a kind of escapism, an exorcism of what she

terms the spiritual demons of the totalitarian political pressure;

later, there was an investigation (through Shakespeare) of those very

demons. Initially, Shakespeares comedies were appropriated to

stress their abstraction, their theatrical self-referentiality, as subtle

means of critiquing the Romanian society and exposing its short-

comings. In 1964, for instance, Twelfth Night, renamed Noaptea Regi-

lor (The Kings Night) turned the world upside down into a kind of

carnival showing the ckleness of power in a disturbing and unpre-

dictable world. In 1978, As You Like It became politically parodic by

stressing uncertainty. The Taming of the Shrew, where complex per-

sonalities were buried in the incredible amount of cheap horseplay,

showed, underneath its surface, a process not unlike brainwashing,

PAGE 12 ................. 11420$ FRWD 10-20-05 11:12:25 PS

FOREWORD 13

which left the characters addicted only to the circus of farce. But by

1986, the banished Duke Senior began to look very much like the

Romanian dictator Ceausescu; as the political economy began to

fragment, the comedic attacks began to coarsen.

The incisive survey of Shakespearean comedy in the postwar years

nds its parallels in the deployment of the histories, tragedies, and

romances. It is no surprise that Shakespeares histories, especially

the Henriad, were at once the most decisive and the most dangerous,

often escaping punishment because they were constructed by show-

ing competing explanations of political events. Yet even here they

were forcing an audience to exercise choice. The tragedies at rst

seemed to support ideological and Socialist oppression, showing the

force of power and the need for clear rule; they were performed in

ways that seemed to signify the superiority of Communism over capi-

talism by applying idealized Marxist theories involving class struggle.

But they were also made to display consequent social decline, and

to take such weakening of the state and disintegration slowly. By as

early as the 1970s, imaginative directors were seizing on new ways to

present Shakespeares works: Macbeth, for instance, in a 1976 pro-

duction, had no weird sisters, but instead had the predictions and

prophecies as Macbeths own secret thoughts that haunted his con-

sciousness as they haunted his conscience. The king hereafter

prophecy became one of his multiple inner voices. In this way,

Macbeth both enacted and deconstructed the mind of the tyrant

and so educated playgoers in the forces of politics and its govern-

mental and social aftermaths. As the red curtain began to come

apart, Romanian actors increased their performances of the Roman

plays, showing the excesses in Coriolanus, Julius Caesar, and, espe-

cially, Titus Andronicus. Nor are the romances exempt. Calibans

cries for liberty were staged against an autocratic Prospero and,

more tellingly, Gower became the autocrat of Pericles, no only telling

the story of Pericles but commanding the audience when to sit and

how to behave.

The extraordinary strength of this book rests, nally, in the life of

the author herself. She has seen many of these productions and she

speaks from rsthand experience and knowledge. But she also

shows a canny way of recording earlier productions by seeing

through the censorship that caused reviewers, even those most sym-

pathetic to the cause of freedom, to mask their commentary. With

painstaking care and admirable caution, Matei-Chesnoiu picks

through the recent past cries of her own beloved country to show

Shakespearean inections in another place, but in our time. The

observations can be unnerving; but they are also energizing. If we

PAGE 13 ................. 11420$ FRWD 10-20-05 11:12:25 PS

14 FOREWORD

are ever to plumb the depths of Shakespeare, the performances re-

corded in this book will have to be a part of how we do it. They tell

us possibilities about the plays, and about ourselves, which we ignore

at the cost of inexcusable ignorance. And the nal lesson implied in

this book is that the subject is not the political and social forces of

Romania, or of eastern Europe, alone. As Matei-Chesnoiu says ex-

plicitly at one point, they were just as true of an England personied

by a torturer like Topcliffe and an absolutist king like James I. A

study, then, which seems to travel so far from Tudor and Stuart En-

gland always has that period, too, in its sights.

Arthur F. Kinney

PAGE 14 ................. 11420$ FRWD 10-20-05 11:12:25 PS

Acknowledgments

THIS BOOK HAS BENEFITED FROM SUGGESTIONS AND COMMENTS ON EARLY

drafts of specic portions by Frances Barasch and Douglas Brooks.

My thanks go to each of them for their time and efforts. In addition,

the comments and reactions of colleagues to papers based on sec-

tions of this study were also helpful. I have included in this book, in

somewhat different and re-contextualized form, the papers pre-

sented at the World Shakespeare Congress (Valencia 2001), the Interna-

tional Shakespeare Conference in Stratford-upon-Avon (2000, 2002,

2004), and the Shakespeare in Europe conferences (Four Centuries of

Shakespeare in Europe, Murcia, 1999; Shakespeare in European

Culture, Basel, 2001; Shakespeare in European Politics, Utrecht,

2003). The nal version responds to the comments and criticism of

anonymous readers for Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, whom

I thank. I am also grateful to Harry Keyishian, Director of FDU Press,

for the benevolent guidance in the nal stages of abridgement of

the manuscript, and especially for the much-needed urging to trim

the book for its gratuitous bulk and its infelicities of style. Many of

these still remain, I am afraid, despite my efforts, and these things

of darkness I acknowledge as mine.

The early research and initial drafting of this study were greatly

facilitated by a Jubilee Education Grant for research at the Shake-

speare Centre Library and Shakespeare Institute Library in Stratford-upon-

Avon and by some research time at the Shakespeare Library in Munich.

I was especially aided by a Fulbright Scholar Grant for the World

Shakespeare Bibliography at Texas A&M University. My special thanks

go to Roger Pringle, Susan Brock, Ingeborg Bolz, and James L.

Harner, without whose help none of this would have been possible.

Arthur F. Kinney has a special place in my appreciation order, and

this is not only for having accepted to write the foreword to this pa-

limpsest-like book, which is the result of extensive collaborative ac-

tivity.

Most of all, I am grateful to my family, who have been proud and

supportive of my academic successes, though at times they found it

hard to accept the apparently stronger relationship with my com-

PAGE 15

15

................. 11420$ $ACK 10-20-05 11:12:34 PS

16 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

puter. I thank all the people, Shakespeare colleagues and friends,

who have been beside me and have helped in the fashioning of ideas

and in sorting out the relevant matter. There is a signicant name

for my approach to Shakespeare in almost each country of Europe,

and I must mention Werner Bronnimann, Ton Hoenselaars, Jona-

than Bate, Mariangela Tempera, Angel Lu s Pujante, Andreas Hof-

fele, Manfred Pster, Krystyna Kujawinska, Holger Klein, and Ina

Schabert. My apologies to those I could not mention and to my Ro-

manian colleagues. The Bucharest National Theater, the Cluj Na-

tional Theater, and the Nottara Theater (Bucharest) provided me

with the copyright for the illustrations of Romanian Shakespeare

productions, for which I am very appreciative. For what I have stum-

bled upon and found, I am grateful to all.

PAGE 16 ................. 11420$ $ACK 10-20-05 11:12:34 PS

Shakespeare

in the Romanian

Cultural Memory

PAGE 17 ................. 11420$ HFTL 10-20-05 11:12:39 PS

This page intentionally left blank

1

Mapping Shakespeares Globe

in a Global World

THIS STUDY SEEKS TO EXTEND THE VIEW OF TRADITIONAL SCHOLARSHIP

regarding Eastern European space and the products of national cul-

tures by considering Shakespeare as a location of specic cultural

history, particularly in the Romanian conguration. As Stanley Wells

pointed out when writing about the integration of Shakespeare in

European culture, the study of Shakespeares impact in languages

other than those in which they originated can . . . be a two-way pro-

cess, blessing those who give as well as those who receive.

1

The ben-

et of studying Shakespeare, whose plays, for during at least the last

two centuries, have gradually permeated European culture in forms

and accents until recently yet unknown, can be equally rewarding to

Anglo-American scholars as it is to researchers whose native lan-

guage is not English. By partaking in the intellectual feast con-

structed around the Shakespearean paradigm, the diversied

European cultures and academics all over the world could experi-

ence a sense of unity while speaking the same language of the the-

ater and sharing a similar set of values. The result is, as Wells

observed in quoting Balz Engler, that Shakespeare takes on the

status of a maker, sometimes a transmitter of myths, in plays relating

no more directly to their ancestral texts than his own plays do to

Homer, Ovid, or Boccaccio.

2

In studying the representation of

Shakespeare elsewhere, we apply the same refurbishing and assimi-

lation method that he had used when constructing his dramatic rep-

resentations of the region of Eastern Europe under scrutiny. The

effect is a different structure, which would be as unrecognizable to

Shakespeare and his contemporaries as their understanding of these

regions must have been to their sixteenth-century inhabitants. How-

ever, this conceptual system of reconsidering cultural boundaries

using the Shakespeare criterion is a mental construction that grows

into something of great constancy.

Unable to resist the chiastic formulation of this chapters title, and

PAGE 19

19

................. 11420$ $CH1 10-20-05 11:12:57 PS

20 SHAKESPEARE IN THE ROMANIAN CULTURAL MEMORY

aware of the inationary usage of this semiotic concept

3

in cur-

rent critical discourse, I consider mapping as a cognitive attempt at

describing the theatrical world of Shakespeare both physically,

through an account of productions, and mentally, by critical inter-

pretation. The abstraction and materiality inscribed in the carto-

graphic activity is aligned here to the theatrical action. With similar

permeable boundaries between the metaphorical and the material,

the theater has a special way of negotiating physical and intellectual

space, showing, if needed, that a disconcerting innity of angels can

be seen dancing on the point of a pin. In the introduction to the

collection of essays debating the politics of space and its negotiation

in early modern Britain, the editors document the signicant

changes in European spatial consciousness brought about by the ex-

ceptional development of cartography from the fteenth century

onwards. As Gordon and Klein observed, A spatial model that re-

quired a geographical centre, an omphalos, in order to describe, in

degrees of civilization, its difference from a diffuse periphery, was

slowly replaced by a framed geometric image fully available for Eu-

ropean inscription.

4

During the process of slowly replacing a

classical and medieval conceptual paradigm of concentric spatial re-

lationship with a more liberal mental organization of human space,

there appear certain cultural shortcuts. The theater is one of these

instructive bypasses because it helps audiences visualize distant

places instantly, with the help of some trick of imagination.

When trying to dene the area of Southeastern Europe where Ro-

mania lies, I have encountered a serious difculty. The author of a

comprehensive Web page about this region seems to share my con-

fusion, which he/she intends to alleviate by invoking the plurality of

readings. K. Feig wonders about the different English names given

to what I will call generically Eastern Europe when he/she writes,

Eastern Europe? Central Europe? East Central Europe? Southwestern

Europe? Southeastern Europe? The Balkans? What name shall we use?

The groupings are illusive and changingbased on myth, tradition,

dreams, treaties, geography, trade-offs, history, symbols, perceptions,

prejudice, power politics, arrogance, ignorance, and HOPE. The con-

cepts of Balkans and southern bring erroneous or incomplete

images of unique civil wars, hatred, barbarism, primitive, poor, irre-

deemable. The concept of central brings the same erroneous or in-

complete images of uniquely civilized, developed, western values. Is

it any wonder that the nations bordering the western and civilized

nations such as Germany and Austria exert enormous effort to link

themselves to them and distance themselves from the other? Is it a

region? What is it? The reader will need to make his/her own distinc-

PAGE 20 ................. 11420$ $CH1 10-20-05 11:12:57 PS

1: MAPPING SHAKESPEARES GLOBE IN A GLOBAL WORLD 21

tions. Whatever else, the civilized nations of the world in the 20th cen-

tury have treated this area with disdain, indifference, frustration, and

reacted with ignorance, hubris, cruelty, and discrimination.

5

Despite the radicalness of such a statement, this is how things stand

about denitions and global assertions at the beginning of this mil-

lennium. Therefore, Eastern Europe and Romania, in my accep-

tance, are not necessarily exact geographic places. Rather, they are

sites, or areas set aside for some precise purpose, and more speci-

cally sites of European cultural memory conserved for the study of

Shakespeare.

Whatever the early modern British playwrights and theatergoers

knew about the south-eastern European territory containing the

Carpathians, toward the lower end of the Danube where it ows into

the Black Sea, was initially conditioned by the ancients writings

about these places. How these classical discourses were transferred

into the domain of common knowledge for the Elizabethans and

Jacobeans is still a matter of debate. However, the general idea for

the early modern readers and theatergoers was that this area of East-

ern Europe, under Turkish domination at the time, was off-limits for

the civilized nations. John Gillies applies a phenomenological cri-

tique to the scene of cartography in King Lear, linking map-reading

in the early modern period to the creation of a new experience of

the bourgeois domestic interior.

6

This expansive interiority,

7

as

Gillies puts it, can explain the dominantly positive mood of recep-

tion and the popularity of cartography in this period, but I see it as

the inherent source of many misconceptions. Since the far-seeing

body is comfortably at home,

8

much of the information conveyed

through the maps cannot be veried. Therefore the facts are often

unreliable, and some data is generally derived from the classics. Ab-

sorbing indiscriminately the information proceeding from the abun-

dant translations of the classics and spicing it with some extravagant

reports from the travelers in those regions, the majority of the Brit-

ish developed a dogmatic and vague notion about much of the land

that lay beyond their immediate center of vision. Despite the abun-

dance of geographical information and the plethora of discourses di-

gesting the works of the classics, early modern readers and audiences

still considered the distant Eastern European spaces as marginal, a

land of elsewhere full of dangers and disagreeable surprises.

Travelers and geographers only apparently succeeded in dissipat-

ing this informational obscurity. In dening the spatial and cultural

coordinates of distant regions more or less accurately, the travelers,

cartographers, and historiographers implicitly circumscribed their

PAGE 21 ................. 11420$ $CH1 10-20-05 11:12:58 PS

22 SHAKESPEARE IN THE ROMANIAN CULTURAL MEMORY

concepts to a strict delimitation between home and foreign. In

addition, not many of those who provided cartographic or ethno-

graphic data ventured farther than Western Europe, except for

those who did business with these countries or were involved in

some sort of extraordinary adventure in the region. Most early mod-

ern instructive accounts about Eastern European places, including

the popular Theatrum Orbis Terrarum by Ortelius, were inspired from

the writings of the classics and contained practical information

about this area of Eastern Europe adorned with splendid maps.

9

Lit-

tle attention was given to the fact that the references to these regions

were those used in classical Latin cartography, or that the names of

the peoples inhabiting them were extracted from ancient texts. It

seems that the visual component and the attraction of the interest-

ingly designed maps were more likely to determine the canon of

relevance for Shakespeares contemporaries than the accuracy of

authentic information. Similarly, the exotic and eccentric facts

about the foreign Eastern European territories, including the three

Romanian provinces, as derived from the classics, were more attrac-

tive to the early modern mind than the reality of those places and

the people who inhabited them. Thus, a myth-making process in-

stantly came into being, and the activity of mentally rewriting con-

ventional illusions about faraway places often replaced the accurate

report.

Unlike his contemporaries, who wrote apparently informative es-

says about various parts of the world, Shakespeare had the ability of

making foreign spaces immediately tangible to his audiences

through the materiality of the theater. Moreover, his plays show how

all the cultural or racial preconceptions can only be deceptive,

obliquely warning everyone not to take too much stereotypical infor-

mation for granted. The study of Shakespeares integration into

modern Romanian culture shows that the people in this part of Eu-

rope, like the other European nations, were ready to welcome the

Shakespeare concept almost at the same time and mostly for the

same reasons. Essentially, three kinds of questions are raised here.

Does the presence of Shakespeare in the discourse of various cul-

tures cast a light on both the history of Shakespeare production and

the respective cultures? How, in certain cases, did the process of

cultural inuenceif anyoperate? Was there an action of inter-

vention, propagation, and transformation of the itemized and stan-

dardized icons provided by the perception of Shakespeare at the

level of a particular country? If the theater is a site for the accumula-

tion of traditional symbols and metaphors, were these particularly

PAGE 22 ................. 11420$ $CH1 10-20-05 11:12:58 PS

1: MAPPING SHAKESPEARES GLOBE IN A GLOBAL WORLD 23

relevant for the Romanians understanding of ethnic, social, and po-

litical relations at a given time?

This informative theatrical tour documents the modern Roma-

nian perception of Shakespeare, seen as a prototype of British cul-

tural identity. A general account of Romanian cultural products and

stage history attempts to show how early translations from Shake-

speare or productions of plays belonging to each genre have con-

tributed to the shaping of a national theatrical selfhood that was

intimately related to the European reception of the English poet. In

analyzing the re-production of Shakespeare in Europe, Balz Engler

calls the early phase of Shakespeare reception Shakespeare beyond

the rules.

10

Linking the early history of European Shakespeares

with the increased signicance of what the English playwright stood

for, Engler comments, The national, even nationalistic, dimension

of Shakespeare re-production is certainly characteristic of Europe,

having to do with the association of language and nation and the

need to translate his works.

11

In surveying the nineteenth-century

translations of Shakespeare in Romania, it becomes visible how vari-

ous translators interpreted the allusions extant in the Shakespeare

text. The underlying inference is that the early Romanian transla-

tors addressed the complex philosophical issues in the tragedies in

a particularly orthodox mode. Despite the popularity of the Roman

plays with the theatrical audiences in the three provinces, and later

in the unied Romania, the four tragedies, Hamlet, Macbeth, Othello,

and King Lear, provided material that could satisfy the publics need

for interiority. In addition, the cultural authority of the Shakespeare

gure was perceived as a means of facilitating the countrys exit

from the status of a marginalized Balkan elsewhere. By promoting

mostly the translations of Shakespeares plays that they perceived to

raise the universal issues of humanity, Romanian intellectuals dur-

ing the 1848 revolutionary period and later hoped to advance the

peoples cultural interests and integrate them in the European fam-

ily of nations.

Considering the association between theater and history, my dis-

cussion follows the Romanian productions of Shakespeares history

plays during the 1980s and 90s. Seeing the theater as an escape

from the adversities of life, as well as a cultural space where pent-up

frustrations and fears could be exorcised, the Romanian audiences

in the Communist period expected political theatrical readings of

Shakespeares histories. During the eighties in Romania, there was

a severe split between what people thought and what they were told

to think. An unstable and ofcially constructed illusion of reality col-

lided with the social and moral disaster obvious to everyone. The

PAGE 23 ................. 11420$ $CH1 10-20-05 11:12:59 PS

24 SHAKESPEARE IN THE ROMANIAN CULTURAL MEMORY

Communist ideologists could no longer control peoples minds by

providing their fabricated version of history, in conict with an in-

creasingly unstable reality. The public developed an illicit taste for

resistance and subversion, which could be materialized in the theat-

rical encounter between author, director, and audience. In this

period, producing Shakespeare, and especially the plays about En-

glands past, was seen as a passive form of resistance against the

Communist ideology, which the disintegrating regime was propagat-

ing ever more feebly. The ensuing democratic mutation of the nine-

ties in Romania brought an increased interest in the production of

Shakespeares English histories by the theatrical companies. Being

no longer encumbered by the need to avoid political censorship or

to provoke latent disruptive meanings, Romanian directors focused

on staging the histories as effective cultural conjunctions between

nations. Directors in the nineties saw the international language of

the theater and politics as a convenient form of emerging from the

status of former cultural isolation. Consequently, the plays drawing

on English history tended to represent a form of multinational the-

atrical export. They became apolitical and ahistorical aesthetic

means of communication rather than instruments of political sabo-

tage.

In examining how Shakespeare has been initially appropriated

and gradually localized in Romanian theater, we see that he shaped

the national dramatic arts while his plays were being internalized.

Shakespeare becomes a paradigm of cultural evolution and the

theatrical maturity of this nation. In the early hard Communist pe-

riod (194960), when the power wanted to legitimize its control

over Romanias past and present in every possible way, producing

Shakespeare extensively was a form of elevating accreditation. In

this period, the production of the comedies was a viable cultural

project from the perspective of the authorities, because these plays

were less concerned with political issues and could be dramatized

successfully in social modes. In the decades of Communist rule be-

tween 1970 and 1990, however, Shakespeare was transparently put

to ideological uses, and directors at local and central theaters be-

came more involved in undermining the collapsing Communist re-

gime by reshaping mentalities about the prerogatives of power. In

this period, the productions of Shakespeares comedies and trage-

dies disclosed specic political agendas and were used explicitly with

subversive purposes. I would like to think that the Romanian the-

aters dissident inuence over two decades of producing Shake-

speare had somehow induced the psychological mood that led to

the 1989 political displacement of autocracy in the real world. In

PAGE 24 ................. 11420$ $CH1 10-20-05 11:12:59 PS

1: MAPPING SHAKESPEARES GLOBE IN A GLOBAL WORLD 25

the nineties, liberated from the straight jacket of political meanings,

theaters and directors concentrated on what the productions of

Shakespeares comedies and tragedies represented for the Roma-

nian theater. In an intensifying self-reexive enthusiasm, directors

paraphrased previous theatrical styles of producing Shakespeare

and devised their own translations and adaptations of the plays.

Thus, many productions have become sophisticated affairs that must

be decoded by specialists, armed with rened deciphering systems.

The history of producing Hamlet on the Romanian stage goes par-

allel with the reception of Shakespeare in Romania in different peri-

ods. However, a cogent discussion about this play needs a separate

chapter, not being included in the series of productions of trage-

dies, because of the exceptional popularity of this play with Roma-

nian audiences ever since the beginning of its translation and

production. The early twentieth-century productions replicated the

romantic-hero vogue derived from the French and German inter-

pretations, and the declamatory style of the actor interpreting the

main hero was directly proportional with the stars fame and posi-

tion in the national theater. Interpreting Hamlet at that time was

equivalent to an international passport to recognition and fame.

Producing Shakespeare in general, and Hamlet especially, came to

be regarded as a rapid way of emerging from the marginal status of

cultural provincialism. Entering through the grand gate of Hamlet

could secure a lasting place in the patrimony of world culture. Dur-

ing World War II, productions of Hamlet were scarcer than ever, be-

cause of the war crisis. However, the plays political cargo was

exploited in a barely recorded production of the play in a political

war prison, where anti-Nazi allusions were evident. The story of the

postwar Communist Hamlet in Romania, however, is a matter of cul-

tural sophistication, even audacity. The early Soviet-inuenced

Communist authorities thought that by producing Shakespeares

most admired play, they would gain the emblem of nobility in cul-

tural matters. In later years of totalitarian domination, however, di-

rectors used Hamlet to suit their personal political tentative of

undermining the Communist regime through the doublespeak of

Shakespeares tragedy. The Romanian Hamlet of the nineties, in a

period when political pressure and the need for subversion were no

longer valid, became once more a theatrical passport through which

a smaller culture intended to bring its tribute to the larger world

cultural heritage. Moreover, in a 2001 Romanian production of

Hamlet by Vlad Mugur, the director faced his own mortality in direct

relation to this play, thus introducing an element of intimately indi-

PAGE 25 ................. 11420$ $CH1 10-20-05 11:13:00 PS

26 SHAKESPEARE IN THE ROMANIAN CULTURAL MEMORY

vidual approach to Hamlet in the most eloquent, even aporetic,

presentist mood.

It is no wonder that a country belonging to a marginalized Eastern

European space has attempted to exit the peripheral status of a rela-

tively insignicant romance culture by adopting the literary values

of the Western world. Voting for Shakespeare in its Romanian ap-

propriations meant advancing toward the enriching caliber of a re-

ned Western culture, which had always regarded its Eastern relative

as alien and barely civilized, a thing of darkness that they could

hardly acknowledge as theirs. Ancient travelers noted that the lands

in the parts of the Black Sea were extremely unfriendly. Early mod-

ern writers highlighted the social, moral, and cultural decay of the

inhabitants of the three Romanian provinces because of the Otto-

man domination. The wars of the twentieth century and the calamity

of Communism did nothing to change this condition of a second-

rate place and culture among the nations of Europe. However, the

complex way in which this nation chose to adopt the cultural legacy

of Shakespeares dramatic formula has been an efcient manner of

exiting the marginal status and approaching the cultural and social

level of other countries of Europe. Dennis Kennedy calls Shake-

speare a cold warrior when he demonstrates that Shakespeare

was used in Western and Central Europe as a site for the recovery

and reconstruction of values that were perceived to be under threat,

or already lost

12

in the years from 1945 to 1965. Likewise, by adopt-

ing the banner of Shakespeare, Romania has intended and tended

to be no longer a liminal space at the cultural margin of Europe,

but a place somewhere near the Black Sea and the Danube, where

Shakespeare has been performed, translated, and interpreted suc-

cessfully for almost two centuries. Moreover, by evidencing close sim-

ilarities in the adoption of Shakespeare with the other countries of

Europe, Romanian culture received Shakespeare as a passport to

European integration long before the international visas were abol-

ished politically.

PAGE 26 ................. 11420$ $CH1 10-20-05 11:13:00 PS

2

Early Translations of Shakespeare in Romania

ENGLISH TRAVELERS AND GEOGRAPHERS IN THE RENAISSANCE PERCEIVED

the European zone around the Carpathians, the lower end of the

Danube, and the western side of the Black Sea as alien territory.

Here, dangers seemed to lurk from every corner of the rugged and

often inaccessible country, or monstrous and savage natives who

showed evil habits made any civil exchange impossible. Moreover,

this was the dominion of the Great Turke, and, therefore, most in-

auspicious for Westerners. All these cultural and racial preconcep-

tions were derived from or capitalized on the classical stories about

these places, available in a multitude of early modern translations.

The plethora of popular geographical texts and atlases, which

mostly took over the information about these regions from the clas-

sics, offered factual details and some basic data about a country that

signied next to nothing for the English traveler or theatergoer.

The merchants and adventurers, who had all sorts of experiences in

the eastern Mediterranean and went as far as the Black Sea or Rus-

sia, brought back and related especially the stories of wonder and

excess. They looked to the marketable value of their accounts in the

publishing business, which could only be increased if the title page

announced that the story was The true and most wonderful re-

port. In the meantime, the majority of the inhabitants of these

Eastern European regions had little knowledge of what happened

beyond the local area they lived in, and even less about the distant

British Isles. The local population in the three provinces of modern

RomaniaWalachia, Moldova, and Transylvaniawas busy farming

the land, extracting the gold from the mountains, or tending to

their sheep, and did not leave many written records of their activi-

ties.

In a post-Kleinian psychoanalytical study on Race as Projection

in Othello, Janet Adelman writes about a contaminated inner

world of envy in the play. According to Adelman, in Iago, Shake-

speare gives motiveless malignity a body

1

by incorporating the ele-

PAGE 27

27

................. 11420$ $CH2 10-20-05 11:12:58 PS

28 SHAKESPEARE IN THE ROMANIAN CULTURAL MEMORY

ment of envy and frustration of the morality tradition. In the case of

the anomalous and most always negative reports about the geo-

graphic area under discussion appearing in early modern texts, we

could speak of a cultural and ideological contamination of the

discourses about these places. Writings in the period were largely

contaminated with information from the classics about the customs

and habits of peoples in Eastern Europe and elsewhere, generally

either inexact or taken for granted from hearsay. Geographers and

historians in ancient times had few means of verifying the veracity of

the reports about this area, and they recorded information ltered

through other peoples consciousness. When certain classical men

of letters, such as Ovid, for example, had rsthand knowledge of the

western side of the Black Sea and the inhabitants of these regions,

they did not report favorably on them at all. Moreover, the fact that

these provinces were in the Ottoman Turks extending power in

early modern times, at the margins of their empire, was an addi-

tional source of anxiety and negativity in the perception of these

places by Western Europeans. Daniel J. Vitkus documents that the

fear of the Islamic bogey was well established in the European con-

sciousness

2

in the period. In this paradoxical geography of exclu-

sion, Shakespeare had no choice but to perceive this area as

marginal, when he did at all. The Shakespearean plays unusual to-

pography incorporates a note of liminality, which he adapted from

the classical and early modern geographical texts.

Analyzing the impact of foreigners on the early modern commu-

nity and culture in a study on Elizabethans and foreigners, G. K.

Hunter notes the large amount of information on physical geogra-

phy accessible to the Elizabethans, almost similar to the modern

availability of such knowledge. However, in point of the framework

of social, psychological, and cultural assumptions concerning for-

eigners and distant regions, Hunter observes an overlap

3

in the

early modern periods perception of people from other countries.

The medieval conception of the zones of the earth, centered on a

spiritual Christian geography as well as a physical one, converges

with the modern worldview. Hunter considers the fact that geogra-

phy was a marginal subject in comparison to classical history and lit-

erature in grammar schools, and that throughout the period there

was a strong ambivalence in the attitude to travel.

4

This overlap of

radically different and almost incompatible modes of thought in the

domain of geographical knowledge allows Shakespeare to explore,

swiftly and coherently, the image of the foreigner, the stranger, the

outsider in a dimension which is at once terrestrial and spiritual.

5

Similarly, A. J. Hoenselaars focuses on Hamlet in his examples of

PAGE 28 ................. 11420$ $CH2 10-20-05 11:12:58 PS

2: EARLY TRANSLATIONS OF SHAKESPEARE IN ROMANIA 29

Shakespeares perception of foreignness,

6

asserting that Shake-

speare makes careful distinctions between nationality and national

character. Hoenselaars argues that Shakespeare relies on stereotypes

of national character for stage characterization only. In addition, I

notice that Shakespeare demonstrates a special potential for staging

the tangibility of the national attributes of peoples in the world

through the physicality of the individual places, whether central or

marginal to the English shores. The stereotypes of national charac-

ter are subtly dismantled and turned to mean differently, in signi-

cant contrastive modes, while the audiences are given a glimpse of

the foreign spaces from the interior, from their inhabitants per-

spective.

All the knowledge the early modern English audiences and artists

had about the farther Eastern European space where Romania lies

was through the accounts of travelers (rsthand or reported) and

historians (classical and contemporary), and through the maps

about these places. Arthur F. Kinney discusses the impact of the rap-

idly growing chorography on mid-sixteenth-century European imag-

ination of foreign places. Seeing that maps, like poems, work with

images functioning as symbols, Kinney notes, Beyond the self-

referentiality within the mapthe chiasmus of meanings in its sym-

bolic corners, for instancethere is referentiality to the culture that

produces it, and to the reader who reads it.

7

Like in the art of the

surveyor or map-maker, in referring to foreign spaces, Shakespeare

produces a spatial triangulation including the mention of a distant

location, some vague knowledge his audiences might have about it

(gathered from classical or early modern sources), and a possible

allusion to his contemporary England. This is proleptically ap-

pended to the plays social and historical context, giving the audi-

ences a real glimpse into distant places that many would never be

able to see.

It is perhaps attractive to speculate on the fact that all the roman-

tic comedies, with the exception of The Merry Wives of Windsor, are

set in extrinsic locations with an exotic avor of elsewhere. So are

the romances, even Cymbeline, since this plays ancient Britain is as

eerie and displaced as many other items of Shakespeares errant ge-

ography. This may be a way of attracting his audiences attention to

the existence of the marginal territories, by making them as real and

tangible for the people coming to the theater as the encircled space

of the Globe they occupied. Considering the island space as a po-

tently image-making factor induced by the atlases and chorograph-

ies of that period, Jonathan Bate sees the island as a special

enclosed space within the larger environment of geopolitics, per-

PAGE 29 ................. 11420$ $CH2 10-20-05 11:12:59 PS

30 SHAKESPEARE IN THE ROMANIAN CULTURAL MEMORY

haps like the enclosed space of the theatre within the larger environ-

ment of the city.

8

Similarly, distant spaces from Eastern Europe,

Asia, or Africa function in Shakespeare as so many islands of geo-

graphic imagination, triggering connotations of alterity.

Unlike the hypothetical and highly conceptualized locations of

the otherwise very popular maps, chorographies, and atlases, or the

repetitive and often obscure geographical descriptive discourses,

Shakespeares theater shows the audiences that there are other par-

ticular, concrete, though distant, places to think or imagine about.

This process of theatrical geographic projection and visualization,

more efcient than any Mercator scientic system, will always work

on increasingly numerous and multinational audiences in the centu-

ries to follow. Each individual production of a Shakespeare play

brings on stage an often-exotic space of Europe or the Mediterra-

nean basin, but it also projects the audiences cultural assumptions

about that space. The larger the sphere of the spectators geographi-

cal and historical knowledge extends, the more efcient the theatri-

cal projection is. According to this imaginative spatial expansion,

like in Blaise Pascals

9

graphic image representing the extent of

human knowledge, we have a circle whose center is everywhere and

the circumference nowhere.

Such diffuse and multiple visualizations of foreign spaces in the

productions of Shakespeares plays can be paralleled with a no less

complex appropriation of Shakespeare in Eastern European cul-

tures. Before analyzing how the Shakespeare myth is implicated in

the fashioning of Romanian national culture, a survey of various per-

formance paradigms and their inection in the production history

of national cultures in the eastern area of Europe is required. Susan

Bassnett spoke about the new transformation and enculturation of

Shakespeare when she wrote, Shakespeare, that great national

icon, has been made and remade as often as ideas of Englishness

and Britishness have been refashioned.

10

Similarly, shedding light

on the category of quotation with relevance to Shakespeare, John

Drakakis noted that Shakespeare now is primarily a collage of fa-

miliar quotations, fragments whose relation to any coherent aes-

thetic principle is both problematical and irremediably ironical.

11

In the current context of Shakespearean appropriations in Europe

and the world, a large number of publications demonstrate that

each cultural milieu has attempted to redene and interpret Shake-

speare within their existing terms by injecting historical and local

aspirations, anxieties, and distancing motivations into the produc-

tion of plays. Joseph G. Price

12

treats Shakespeare as the cultural

phenomenon of the post-Renaissance world, which now extends be-

PAGE 30 ................. 11420$ $CH2 10-20-05 11:13:00 PS

2: EARLY TRANSLATIONS OF SHAKESPEARE IN ROMANIA 31

yond Western boundaries to comprise every culture, including pop-

ular culture. Only in the last decade, more than twenty book-length

studies, collections, and monographs have appeared to testify to the

interesting issue of various national appropriations of Shakespeare.

Dennis Kennedys collection of essays entitled Foreign Shakespeare

13

and the collection of articles edited by Michael Hattaway, Boika So-

kolova, and Derek Roper

14

opened the way for many creative critical

responses to Shakespeare in different cultures.

Shakespeare and National Culture edited by John J. Joughin

15

contin-

ues the project begun by cultural materialists of uncovering the po-

litical and social uses according to which the Shakespeare text has

been appropriated, adapted, and reinvented. Part I of the collection

of essays refers to colonial and anti-colonial appropriations of

Shakespeare, with focus on the Indian and South-African cultures,

and Part III (Shakespeare at the heart of Europe) is an extension

and sharpening of the debate concerning the question of nation-

hood and its associate fantasies. The meaningful contributions by

Thomas Healy

16

and Francis Barker

17

focus on nding the fault lines

and continuities between past and present in the representations of

the protean Shakespeare in Europe. Robert Weimann

18

gives an ac-

count of the contradictory uses to which Shakespeare was put in

postwar Germany, establishing the vexed relations of intellectual au-

thority and political power of Shakespeares appropriation in the

German Democratic Republic. Weimann argues that the Enlighten-

ment roots of a classicized version of Shakespeare resulted in a

literary intellectualized presentation rather than a popular interpre-

tation of the plays. The conservative approach became a national

icon that was employed by the Marxist-Leninist authorities of the

GDR to promote the idea of Shakespeares works as splendid pre-

gurations of their own Socialist-humanist ideals. This conscation

practice is largely similar, I would add, to the postwar reconsidera-

tion of Shakespeare in the other Communist countries of Central

and Eastern Europe, including Romania.

Speaking of the resistant and subversive signicance of a mimed

production of Romeo and Juliet in Bulgaria, in the same collection of

essays edited by John Joughin, Thomas Healy makes the analogy

with the hole in the Romanian ag during the 1989 revolution. As a

symbol of their rejection of the old Communist order, the Romani-

ans had cut the Communist coat of arms out of the center of the

ag. However, as the old order appeared in new guises only months

later, the signal of change was beginning to look increasingly sus-

pect. In asking about the signicance of a hole in the ag, a declara-

tion of change, a denial of the past, the answer Healy suggests is an

PAGE 31 ................. 11420$ $CH2 10-20-05 11:13:00 PS

32 SHAKESPEARE IN THE ROMANIAN CULTURAL MEMORY

acknowledgment of absence

19

and an uncertainty of meaning. I

would extend the analogy of absence by suggesting a Shakespearean

model of the cipher, which stands in a high place, but only ap-

pears to be nothing in itself, because its presence raises the value of

the unity neighboring it. Similarly, in the histories of incorporation

or, rather, dislocation and displacement of the Shakespeare text by

various national cultures, the vacuity, partial irrelevance, or even

total absence of the literary side of the plays texts only adds to the

dramatic eminence of performativity inherited from and inherent

in this theater. As Healy puts it, the multiple Shakespeares have de-

veloped their own hegemonic practices which silently assume Shake-

speare as a civilizing force, whose continuing presence, whether

drawn from English Renaissance, French Enlightenment, or Ger-

man romantic traditions, illustrates cultural advancement.

20

In

moving forward on this practice-paved theatrical way toward Roma-

nia, one of the inglorious areas of Eastern Europe once referred to

as elsewhere, it is increasingly evident that the way this country

appropriated Shakespeare, in both the theater and literature, quali-

es Romania as a landmark for European Shakespeare theater.

Russian Shakespeare scholarship and theater designates another

area of Eastern Europe that inherited and transformed the associa-

tions and inections of the Shakespearean tradition. The collection

of essays edited by Alexander Parfenov and Joseph G. Price

21

ex-

plains the origins of Shakespeares signicance to Russian theater in

the nineteenth century and his pervasive inuence through decades

of Communism. Alexei Bartoshevitchs essay on Soviet Shakespear-

ean productions in the 1960s and 70s charts how vigorously during

that period the Russian theater re-read Shakespeare in terms of

present-day Soviet life. Bartoshevitch states that, after the 1970s, Rus-

sian theater de-romanticized Shakespeare and instead offered politi-

cally charged productions of his plays.

22

The study interprets

Waldemar Pqnsos Richard III (1975) as depicting an anarchic world,

stripped of all signs of lofty tragedy, in which the stage is com-

pletely dominated by ruthless grotesques.

23

This theatrical de-

romanticization of Shakespeare grew out of the traditions of Brecht

and Beckett and out of Jan Kotts Grand Mechanism of history, seen

as a cynical sequence in which the end is the beginning and one

villain replaces another. In this implacable machinery, Richmond

follows in the footsteps of Richard, Macbeth is reincarnated in Mal-

com, Fortinbras takes over after Claudius.

24

The study is energized

by its vivid descriptions of sets, costumes, characters, and actions in

the Russian productions of Richard III, Hamlet, Macbeth, and King

Lear by Pqnso and Robert Sturua. This collection of essays provides

PAGE 32 ................. 11420$ $CH2 10-20-05 11:13:01 PS

2: EARLY TRANSLATIONS OF SHAKESPEARE IN ROMANIA 33

a commendable summary of evolving Russian interests in Shake-

speare in the twentieth century, and points to the fascinating range

of the ideological collisions between the post-Revolutionary Soviet

establishment and the popular resistance, as each has co-opted

Shakespeare for its own purposes.

In a study tracing the reception of Shakespeare in Eastern Eu-

rope, Zdenek Str brny

25

explains how writers, translators, critics, mu-

sicians, and theater personnel have contributed to the knowledge

and appreciation of Shakespeare and how his plays have been ap-

propriated for political purposes. The author pays extensive atten-

tion to Czech, Russian, and Hungarian productions, but this

meritorious study deals with the Romanian substantial contribution

to Eastern European Shakespeare in only three or four pages. More-

over, in an article published earlier, Str brny argues for a cultural

denition of Eastern European spaces mentioned in Shakespeare,

which points toward their perception as alien territory. Examining

Shakespeares allusions to Eastern Europe, the author makes the

case that this area appears mostly as a cold and mysterious wilder-

ness or otherness.

26

This peculiar land of indeterminate location,

however, has adopted Shakespeare in a most uncompromising way,

whatever nation acted as a foster parent. Whether Czech, Russian,

Polish, Hungarian, Serb, or Bulgarian, all Eastern European nations

have encoded Shakespeare in their national performative and liter-

ary presence.

An admirable study by Alexander Shrubanov and Boika Soko-

lova

27

examines the appropriation of Shakespeare in Bulgaria be-

tween 1944 and 1989. Attention is given to the impact of Soviet

aesthetics on productions, the creation in textbooks of a stereotyped

Shakespeare and its relation to the suppression of literary criticism,

the ideological use of productions of the tragedies and comedies,

and the debate about modernizing Shakespeare in the theater. The

authors present Bulgarian productions of Romeo and Juliet and Ham-

let as a Shakespearean mirror held to the fortunes of new Bulgaria,

and the early reception of a childrens version of The Merchant of Ven-

ice as illuminating the perception of the Jew in this country. After a

presentation of the teaching of Shakespeare in Bulgarian schools,

the authors focus intensely on East European uses of the great trage-

dies and the comedies in the Bulgarian context.

The recent collection of essays entitled The Globalization of Shake-

speare in the Nineteenth Century

28

explores the way in which Shake-

speares international reputation was constructed through the

appropriation and subversion of the plays in the canon to suit na-

tional demands and a variety of political and cultural agendas. In

PAGE 33 ................. 11420$ $CH2 10-20-05 11:13:01 PS

34 SHAKESPEARE IN THE ROMANIAN CULTURAL MEMORY

the foreword to this edition, Peter Holland gives an overview of the

nineteenth-century Shakespeare in England and abroad, noting that

the senses in which Shakespeare existed worldwide continually

changed as each country reinvestigated its own relationship with

Shakespeare.

29

We could detect, therefore, a continual process of

readjustment in the reception of Shakespeare in the nineteenth

century. While in Britain the bard was gradually growing into the

most precious of all British cultural objects and a symbol of national

achievement, in Europe and elsewhere in the world, each national

culture was redening itself by adopting the English national factor

as a criterion of cultural accomplishment. As the editors put it

briey and eloquently, Everyone, in short, wanted a piece of Shake-

speare, and these appropriations, in turn, created a tradition of

bardolatry that continues in many quarters until our own day.

30

The various essays in this collection show how in Romania, as in

Flanders and also in Argentina and Brazil in the early nineteenth

century, the neoclassical French adaptations were used to introduce

Shakespeares plays to the respective national cultures.

The history of Shakespeares adoption by Romanian culture is as

rich as any countrys in the Eastern European area. The domains of

Shakespeare scholarship/criticism, translations, literary adapta-

tions, and especially the theater have yielded impressive cultural

products. An early twentieth-century study by Marcu Berza

31

exam-

ines the causes of the attraction of the Romanian public for Shake-

speares plays. Undoubtedly, the elements of folklore contained in

the plays, some of which are taken over even from Balkan oral litera-

ture, constituted, as the author points out, one of the factors ex-

plaining the success of Shakespeare among the mass of the play-

going public in Romania. Alexandru Dutu

32

gives a comprehensive

study of Shakespeares reception in Romania and delineates stages

in this process of appropriation, namely, penetration through inter-

mediaries, contact with original texts, and original interpretation of

producers and critics. Dutu concludes that throughout these stages

Shakespeare contributed toward the development of a taste for

drama and of cultural progress in Romania. Aurel Curtui,

33

in a

book monograph, examines the reception of Hamlet in Romania

with emphasis on translations, criticism, and inuence on Roma-

nian literature and intellectual life. The Romanian critic and transla-

tor Dan Grigorescu

34

studies Shakespeare in the context of modern

Romanian culture and traces Romanian responses to Shakespeares

plays and their signicance, pointing to the specicity of Romanian

culture within the framework of European art. Leon Levitchis name

has long been connected with Shakespearean criticism

35

and transla-

PAGE 34 ................. 11420$ $CH2 10-20-05 11:13:02 PS

2: EARLY TRANSLATIONS OF SHAKESPEARE IN ROMANIA 35

tion,

36

and he edited the rst scholarly edition of the Complete Works

37

in Romanian.

A little while before Shakespeare had come to be perceived as

the epitome of Western culture and civility in modern Romania, in

early nineteenth century, the three provinces that formed this coun-

try had learned about the plays via the German and Viennese

troupes touring their capitals. The cultured elite in these cities, es-

pecially in Walachia and Moldova, were still inuenced by the Turk-

ish customs, but a fresh inux of Western values, especially the

French and German cultures, was a special way of afrming a na-

tional identity in the making. This nation has always aspired to the

values of Western cultures, while the vicissitudes of geography and

politics kept its legs of clay rmly glued to the viscous soil of Levant.

However, along the more than a century and a half since the theatri-

cal and literary dissemination of Shakespeare in the land around the

Carpathians and the Danube, the name has come to signify diverse

but always important issues related to a Western European aspira-

tion. Through the early translations and productions, the national

Romanian literature and the theater partially came to dene them-

selves and emerge as pillars of national culture adhering to Western

European values. In the cultural momentum between the two world

wars, when Romania steadied her cultural pace, the positive and

abundant reception of Shakespeare was always there to witness and

ascertain the authorized notion of high cultural achievement. In the

half-century interval of dire Communist oppression, the plays were

used as sophisticated tools of subversion. In times of democracy,

however, the Shakespeare emblem has become an epitome for the

theater in its excellent abstraction and international neutrality. Inso-

far as modern Romania can be seen as a special place somewhere,

in which Shakespeare is being played meaningfully and actively, the

following pages will try to point out only a few milestones in this het-

erogeneous theatrical atlas.

Early History of Romanian

Translations: Appropriation

In sketching the process by which their Shakespeare became

our Shakespeare in Romania, a non-English-speaking and Latin-

origin culture, the focus is on the appropriation, assimilation, and

transformation of Shakespeares language through translations in

the nineteenth century. When dealing with early translations, a

number of essential questions can be raised. How does Shakespeare

PAGE 35 ................. 11420$ $CH2 10-20-05 11:13:02 PS

36 SHAKESPEARE IN THE ROMANIAN CULTURAL MEMORY

translated into other cultures reveal dimensions of the plays not

apparent in their early modern origins? Is Shakespeare outside En-

glish still Shakespeare? How have the early translations of the plays

served as a vehicle for cultural domination and the dissemination of

ideas? In these terms, translation means both verbal literary treat-

ment, which is the object of this chapter, and more broadly, transla-

tion and interpretation in the theater. Early nineteenth-century

Romanian poets saw in Shakespeare a good vehicle for promoting

their revolutionary ideals, one of the insertion points of cultural

strategies within the political setting of the 1848 revolution. More-

over, the multiple questionings and the ethical issues raised in the

plays, explored mainly in the tragedies, were good ways of raising

the peoples awareness and developing a sense of national identity.

In a period when the three Romanian provinces were still under the

waning inuence of Ottoman rule, a strong moral discernment, de-

rived from the reading and dramatic encounter with Shakespeare,

could only help develop a sense of national identity. The Romanian

peoples sentiment of belonging to the Christian religion was a form

of defending their national identity against the centuries-old offen-

sive of Islam. So was the appreciation of this peoples Latin origin as

an asset against the inuences of both the Islamic south and the

Slavic East.

Examining the current situation of Shakespeare studies and trans-

lation, Dirk Delabastita makes the already famous comment that

translation was the Cinderella of Shakespeare studies,

38

which

had remained the almost exclusive property of the Anglo-American

academic establishment. While subscribing to the idea of the mar-

ginalization of translation studies in general, it seems important to

mention Delabastitas comment inscribing the interest in transla-

tion within a larger romantic concept in the nineteenth century,

which posited the text as a transparent self-representation of the au-

thors intention. From this perspective, the nineteenth century in

Europe was the period when Shakespeare gradually became inter-

national property,

39

playing a major role in the development of na-

tional identities. Translations in this interval were essential for the

dissemination of Shakespeare all over the world, and by translating

the plays, many European nations learned the lesson of intercultural

communication and civil tolerance. Delabastita explains the undis-

puted and indisputable canonized status of Shakespeare as the ulti-

mate icon of literary art,

40

arguing that many nations bestowed on

this literary gure a kind of wisdom and authority of almost meta-

physical depth, thus attributing his plays a transcendental quality. I

have identied a similar situation when surveying the state of nine-

PAGE 36 ................. 11420$ $CH2 10-20-05 11:13:03 PS

2: EARLY TRANSLATIONS OF SHAKESPEARE IN ROMANIA 37

teenth-century translations in Romania, since the translators, proba-

bly involuntarily, identied the moral issues dramatized in

Shakespeares tragedies with a universal ethical paradigm. This led

them to prefer mostly the four tragedies in their rst translation ap-

proaches, probably considering that these plays addressed general

human issues that were essential in the nations cultural advance-

ment during the crucial period of the mid and late nineteenth cen-

tury.

The European context of nineteenth-century translations is im-

mensely rich and has been the subject of extensive scholarship.

41

In

the circumstances of the Shakespearean translations in Western Eu-

rope, the French and German versions have played an important

role in the documentation of early Romanian translations, because

most nineteenth-century translators drew on these interpretations.

The early and popular Ducis versions of Hamlet (1769), Romeo et Julie-

tte (1772), Le Roi Lear (1783), Macbeth (1784), Jean sans Terre (1791),

and Othello (1792) did not inuence early Romanian translators as

much as Le Tourneur or Alexandre Dumas. Just as Ducis drew on

Le Tourneur and Antoine de La Place, Romanian translators did the

same. However, since the Ducis versions were adapted for the the-

ater, notable nineteenth-century Romanian directors drew on these

French versions to forge their own translation of the Shakespeare

text in performance. These Romanian directors translations are not

recorded in print, but there is evidence in the theatrical journals of

the time referring to their creation of personal texts for the theater,

or sometimes only for recitation in literary circles. Le Tourneurs

Shakespeare traduit de lAnglois (177683) in prose is not of very high

quality, but compared with that of La Place (1645) and other con-

temporary efforts, it marks a considerable advance. Voltaires Brutus

and La Mort de Cesar (1731) is inscribed in the French vogue of adap-

tations from Shakespeare, while his translation of Jules Cesar (1769)

was at the basis of a few Romanian translations of fragmentary texts

from this play.

Franc ois Guizot republished Le Tourneurs translation in a re-

vised form (Oeuvres comple`tes de Shakespeare 1821), enabling the

younger generation of poets and critics to investigate further those

enthusiastic eulogies of Shakespeare they found in German roman-

tic writers. Seduced by English romanticism, Alfred de Vigny greatly

contributed to the discovery of Shakespeare in France. In an admira-

ble translation, he transported the English success of Othello to the

stage of the Theatre Francais (1829). During his exile in England,

Benjamin Laroche studied Shakespeare with great enthusiasm, and

spent many years devising a translation into French. His Oeuvres com-

PAGE 37 ................. 11420$ $CH2 10-20-05 11:13:03 PS

38 SHAKESPEARE IN THE ROMANIAN CULTURAL MEMORY

ple`tes (1839) was a success, and he received a prize for the best ver-

sion of Shakespeare. The result of a similar exile to Guernesey,

Francois-Victor Hugos translation of Shakespeares Oeuvres comple`tes

(185772), written with an introduction by his father, Victor Hugo,

and especially his Hamlet, were important source texts for Romanian

translators. The French literary critic Emile Montegut produced the

Oeuvres comple`tes in ten volumes between the years 186873. His opus

is another landmark of inspiration for Romanian translators of

Shakespeare. The version of Hamlet by Euge`ne Morand and Marcel

Schwob (1899), despite being in prose, was considered to have a re-

markable delity to the original. It inuenced Romanian early twen-

tieth-century theater directors in forging their translations for

performance, when they did not use the already published literary

versions.

Like the French, the domain of nineteenth-century German criti-

cism and translation of Shakespeare is an extensive source for schol-

arship in the history of the appropriation of Shakespeare in Europe,

though it is manifested in less decorative forms. I cannot hope to

comprehend the entire province of German translations of Shake-

speare, but I will try to point out those translators that are likely to

have played a role in the selection of the inspiration source texts

for the Romanian Shakespeare translations. Most of these German

translators are not acknowledged on the front pages of the Roma-

nian versions. Extensive research is still needed to identify the exact

text on which each Romanian version is based. However, it is reason-

able to assume that some German translations were at the basis of

early Romanian productions of Shakespeare in the three provinces,

especially in Transylvania, where the German and Austrian inu-

ences were preeminent. Wieland (176266) and the Austrian Franz

Heufeld (1772) rst translated Hamlet into German. In 1776, Germa-

nys greatest actor, Friedrich Ludwig Schroder, produced Hamlet in

Hamburg, he himself playing the ghost. In the same year followed a

production of Othello, in 1777 The Merchant of Venice and Measure for

Measure, and in 1778 King Lear, Richard II, and Henry IV. Macbeth was

produced in 1779 and Much Ado about Nothing in 1792. The chief

impression we obtain from Schroders Shakespearean versions now-

adays is their inadequacy to reproduce the poetry of the originals.

However, compared with the travesties of Ducis a little later, they

may be seen as examples of scrupulous translation.

Schroder adapted the Wieland and Heufeld translations of Ham-

let, but he gave way to public pressure in adding a sixth act. This

contains, among other things, the gravediggers scene, which had

formerly been suppressed, presumably because it was felt to be out

PAGE 38 ................. 11420$ $CH2 10-20-05 11:13:04 PS

2: EARLY TRANSLATIONS OF SHAKESPEARE IN ROMANIA 39

of keeping with the tone of high tragedy. Schroder was obviously still

not fully comfortable with the additional scenes, because they are

dropped from the second edition (1778). Comparison shows that

Heufelds version is heavily indebted to Wieland, just as Schroders

is to Heufeld. However, Wielands text is more urbane than the

other translations, which are redolent of the incipient Sturm und

Drang movement. This literary trend, in its turn, owed much to the

inuence of Shakespeare. These early German translations of

Shakespeare were the models for the Romanian early nineteenth-

century versions, especially of the tragedies. August Wilhelm

Schlegel, Ludwig Tieck, Wolf Graf von Baudissin, and Friedrich

Schillers Macbeth (1801) and Goethes Romeo und Julia (1812) are

only two products of some of the renowned German scholars who

translated Shakespeare in the nineteenth century. Their books must

have existed in the private libraries of those Romanian intellectuals

who had been educated in the universities of Germany and Austria.