Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Demeter and Persephone

Uploaded by

Eleanor OKellCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Demeter and Persephone

Uploaded by

Eleanor OKellCopyright:

Available Formats

Demeter (and Persephone)

For younger participants (because of the way the story is told – with no

abduction or rape – in schools) LightNight imagines that the story of Demeter and

Persephone has already happened – i.e. Demeter and Persephone are already used to

spending part of the year apart. However, Demeter is reluctant to see her daughter go

every year and this year has come down to the underworld to isit her – but she doesn’t

know the way and Persephone isn’t epecting her. Hence, she is searching for

Persephone and Pluto’s palace, where Persephone is happily living with her husband

Hades, although she still misses her mother terribly.

This enables Persephone more easily to interact with Orpheus as if she is the

established Queen of the Underworld, without having to engage in swift temporal

shifts if Demeter finds her at the same time as Orpheus.

Otherwise, stick with the sources – including abduction (but not rape). I’e left

out Ovid (Met. 5) on the grounds that Ovid does everything to erradicate any hint of

marriage or betrothal and emphasise seual desire and the violence of Pluto’s attack.

Alternatively, some later sources (e.g. Claudian) show Hades’ emotions and go so far

as to subtly suggest the Proserpina falls in love with him.

Demeter starts in City Square among the Eleusinian initiates and asks for help

to find Persephone, who is located in the portico of the Town Hall.

All interactions are improvised, based on the following sources.

Demeter (and Persephone)..........................................................................................1

The Story in Brief.......................................................................................................1

The Eleusinian Mysteries...........................................................................................2

The Value of being an Initiate....................................................................................3

Homeric Hymn to Demeter (trans. H. P. Foley)........................................................3

Claudian, The Rape of Proserpina (extracts of an incomplete epic poem, trans. D.

R. Slavitt).................................................................................................................13

The Story in Brief

Apollodorus, The Library 1.5

Pluto fell in love with Persephone and with the help of Zeus carried her off secretly.

But Demeter went about seeking her all over the earth with torches by night and day,

and learning from the people of Hermione that Pluto had carried her off, she was

wroth with the gods and quitted heaven, and came in the likeness of a woman to

Eleusis. And first she sat down on the rock which has been named ‘Laughless’ after

her, beside what is called the ‘Well of Fair Dances’; thereupon she made her way to

Keleos, who at that time reigned over the Eleusinians. Some women were in the

house, and when they bade her sit down beside them, a certain old crone, Iambe,

joked with the goddess and made her smile. For that reason they say that the women

break jests at the Thesmophoria.

But when Zeus ordered Pluto to send up the Maid [i.e. Persephone], Pluto gave her a

seed of a pomegranate to eat, in order that she might not stay long with her mother.

Not foreseeing the consequence, she swallowed it; and because Askalaphos, son of

Acheron and Gorgyra, bore witness against her, Demeter laid a heavy rock on him in

Hades. But Persephone was compelled to remain a third of every year with Pluto and

the rest of the time with the gods.

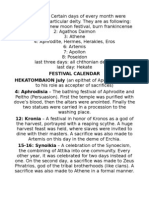

The Eleusinian Mysteries

Little Mysteries (Anthesterion = Jan./Feb.)

Washing in the river Ilissos

Great Mysteries (Boedromion = Aug./Sept.)

14th – procession from Eleusis to the Athenian Eleusinion, with hiera (‘holy things’)

in kistai (round boes), accompanied by ephebes

15th – ‘Gathering’ at the Athenian Eleusinion

16th – ‘To the sea, initiands!’ – a procession to the sea; sacrifice of a pig; bathing;

return to Athens

17th – ‘Hither the ictims’ – state sacrifice in Athens

18th – Epidauria festival from 420BCE (arrial of Asclepius)

19th – procession to Eleusis, with statue of Iacchos and heira, accompanied by

ephebes

20th – fasting and all-night initiation ceremony in the Telesterion at Eleusis

21st – Plemochoai (‘water-carrying jugs’) – water ritual; dedication of clothing

Varro Antiquities fragment

Of these [the rites of Eleusis] he (arro) makes no interpretation except in relation to

Demeter’s discovery of corn and her loss of Persephone when Pluto seized her. He

says Persephone signifies the fertility of the seeds: for, when it failed on one occasion

and the earth mourned at this sterility, the opinion arose, so he says, that the daughter

of Demeter – i.e. the actual fertility – had been stolen away by Pluto and detained in

the Underworld. This was marked by public mourning. Then, since the fertility came

back again, joy arose at the restoration of Persephone and as a result a festival was

instituted. He proceeds to say that much is passed on in her mysteries which refers to

nothing other than the discovery of corn.

Aelius Aristides, Eleusinian Discourse

What Greek, what non-Greek has been so pererse, so ill-informed… that he did not

consider Eleusis a shrine common to the earth, and of all man’s divine possessions

both most fearsome and most gladdening? For what other places have the utterances

of myths made hymns more astounding, have the dromena had greater impact, have

the things seen been more of a rial to what is heard? As for the things which may be

obsered go, they have been seen by countless generations of happy men and women

in showings which may not be spoken of. But what is public, poets and chroniclers

and historians, all of them, hymn: how Demeter’s Maid anished for some time, how

Demeter went over the whole earth and sea searching for her daughter, how for a

while she could not find her, but when she came to Eleusis she gave the name to the

place and, having found the Maid, created the Mysteries.

Lactantius Divine Institutes, Epitome 23

The mystery of Demeter too is similar to these (the rites of Isis). In it torches are lit,

and through the night Persephone is searched for; and when she is found, the whole

rite ends with celebration and shaking of torches.

From Christian writers (Clement and Arnobius) we know that the synthema

(formula/password) of the Eleusinian Mysteries is: ‘I fasted; I drank the kykeoin; I

took from the chest. I enacted; I returned to the basket, and from the basket to the

chest.’

The Value of being an Initiate

Homeric Hymn to Demeter 480-82

Blessed is he who of men on the earth has seen these things,

But he who is uninitiated in the rites, who has no share, never has

for his portion similar things when he is perished beneath the squalid dark.

Pindar frag. 121

Blessed is he who having seen these things

Goes beneath the earth:

He knows the end of life;

He knows its beginning god-given.

Sophocles frag. 753

…Thrice blessed

Are they of mortals, who having beheld these rites

Come to Hades: for them alone is it possible there

To live; for the others everything there is bad.

Isocrates Panegyricus 28

Demeter gave these two gifts, the greatest in the world – the fruits of the earth, which

have enabled us to rise above the life of beasts, and the telete (Mystery-Rite) which

inspires in those who partake of it sweeter hopes regarding both the end of life and all

eternity…

Homeric Hymn to Demeter (trans. H. P. Foley)

Demeter I begin to sing, the fair-tressed awesome goddess,

herself and her slim-ankled daughter whom Hades

seized; Zeus, heavy-thundering and mighty-voiced, gave her,

without the consent of Demeter of the bright fruit and golden sword,

as she played with the deep-breasted daughters of Ocean,

plucking flowers in the lush meadow – roses, crocuses,

and lovely violets, irises and hyacinth and narcissus,

which Earth grew as a snare for the flower-faced maiden

in order to gratify by Zeus’ design Hades, the Host-to-Many,

a flower wondrous and bright, awesome for all to see,

for the immortals above and for mortals below.

From its root a hundredfold bloom sprang up and smelled

so sweet that the whole vast heaven above

and the whole earth laughed, and the salty swell of the sea.

The girl marvelled and stretched out both hands at once

to take the lovely toy. The earth with its wide ways yawned

over the Nysian plain; Hades, the Host-to-Many, rose up on her

with his immortal horses, the celebrated son of Chronos;

he snatched the unwilling maid into his golden chariot

and led her off lamenting. She screamed with a shrill voice,

calling on her father, the son of Chronos highest and best.

Not one of the immortals or of humankind

heard her voice, nor the olives bright with fruit,

except the daughter of Persaios; tender of heart

she heard it from her cave, Hekate of the delicate veil.

And lord Helios, brilliant son of Hyperion, heard

the maid calling for her father the son of Chronos. But he sat apart

from the gods, aloof in a temple ringing with prayers,

and received choice offerings from humankind.

Against her will Hades took her by the design of Zeus

with his immortal horses – her father’s brother,

Commander- and Host-to-Many, the many-named son of Chronos.

So long as the goddess gazed upon the earth and starry heaven,

on the sea flowing strong and full of fish,

and on the beams of the sun, she still hoped

to see her dear mother and the race of immortal gods.

For so long hope charmed her strong mind despite her distress.

The mountain peaks and the depths of the sea echoed

in response to her divine voice, and her goddess mother heard.

Sharp grief seized Demeter’s heart, and she tore her veil

on her ambrosial hair with her own hands.

She cast a dark cloak on her shoulders

and sped like a bird over dry land and sea.

searching. No one was willing to tell her the truth,

not one of the gods or mortals;

no bird of omen came to her as truthful messenger.

Then for nine days divine Demeter roamed over the earth,

holding torches ablaze in her hands;

in her grief she did not once taste ambrosia

or nectar sweet-to-drink, nor bathed her skin.

But when the tenth Dawn came shining on her,

Hekate met her, holding a torch in her hands,

to give her a message. She spoke as follows:

‘Divine Demeter, giver of seasons and glorious gifts,

who of the immortals or mortal men

seized Persephone and grieved your heart?

For I heard a voice but did not see with my eyes

who he was. to you I tell at once the whole truth.’

Thus Hekate spoke. Demeter, daughter of fair-tressed Rhea,

said not a word, but rushed off at her side

holding torches ablaze in her hands.

They came to Helios, observer of gods and mortals,

and stood before his horses. The most august goddess spoke:

‘Helios, respect me as a god does a goddess, if ever

withy word or deed I pleased your heart and spirit.

The daughter I bore, a sweet offshoot noble in form –

I heard her voice throbbing through the barren air

as if she were suffering violence. But I did not see her with my eyes.

With your rays you look down through the bright air

on the whole of the earth and the sea.

Tell me the truth about my child. Have you somewhere

seen who of gods or mortal men took her

by force from me against her will and went away?’

Thus she spoke and the son of Hyperion replied:

‘Daughter of fair-tressed Rhea, mighty Demeter,

you will know the truth. For I greatly revere and pity you

grieving for your slim-ankled daughter. No other

of the gods was to blame but cloud-gathering Zeus,

who gave her to Hades his brother to be called

his fertile wife. With his horses Hades

snatched her screaming into the misty gloom.

But, Goddess, give up for good your great lamentation.

You must not nurse in ain insatiable anger.

Among the gods Hades is not an unsuitable bridegroom,

Commander-to-Many and Zeus’ own brother of the same stock.

As for honour, he got his third at the world’s first division

and dwells with those whose rule has fallen to his lot.’

He spoke and called to his horses. At his rebuke

they bore the swift chariot lightly, like long-winged birds.

A more terrible and brutal grief seized the heart

of Demeter, angry now at the son of Chronos with his dark clouds.

Withdrawing from the assembly of the gods and high Olympus,

she went among the cities and fertile fields of men,

disguising her beauty for a long time. No one of men

nor deep-girt women recognised her when they looked,

until she came to the home of skilful Celeos,

the man then ruler of fragrant Eleusis.

There she sat near the road, grief in her heart,

where the citizens drew the water from the Maiden’s Well

in the shade – an olive bush had grown overhead –

like a very old woman cut off from childbearing

and the gifts of garland-loving Aphrodite.

Such are the nurses to children of law-giving kings

and the keepers of stores in their echoing halls.

The daughters of Celeos, son of Eleusis, saw her

as they came to fetch water easy-to-draw and bring it

in bronze vessels to their dear father’s halls.

Like four goddesses they were in the flower of youth,

Callidike, Cleisidike, fair Demo, and Callithoe,

who was the eldest of them all.

They did not know her – gods are hard for mortals to recognise.

Standing near her, they spoke winged words.

‘Who are you, old woman, of those born long ago?

From where? Why have you left the city and do not

draw near its homes? Women are there in the shadowy halls,

of your age as well as others born younger,

who would care for you both in word and in deed.’

They spoke, and the most august goddess replied:

‘Dear children, whoever of womankind you are,

greetings. I will tell you my tale. For it is not wrong

to tell you the truth now you ask.

Doso’s my name, which my honoured mother gave me.

On the broad back of the sea I have now come from Crete,

by no wish of my own. By force and necessity pirate men

led me off against my desire. Then they

put in to Thorikos in their swift ship, where

the women stepped all together onto the mainland,

and the men made a meal by the stern of the ship.

My heart did not crave a heart-warming dinner,

but racing in secret across the dark mainland

I escaped from my arrogant masters, lest

they should sell me, as yet unbought, for a price overseas.

Then wandering I came here and know not at all

what land this is and who lies here.

But may all the gods who dwell on Olympus

give you husbands to marry and children to bear,

such as parents wish for. Now pity me, maidens,

and tell me, dear children, with eager goodwill,

whose house I might come to, a man’s

or a woman’s, there to do for them gladly

such tasks as are done by an elderly woman.

I could nurse well a newborn child, embracing it

in my arms, or watch over the house. I could

spread out the master’s bed in a recess

of the well-built chamber and teach women their work.’

So spoke the goddess. To her replied at once Callidike,

a maiden unwed, in beauty the best of Celeos’ daughters.

‘Good mother, we mortals are forced, though it hurt us,

to bear the gifts of the gods; for they are far stronger.

To you I shall explain these things clearly and name

the men to whom great power and honour belong here,

who are the first of the people and protect with their counsels

and straight judgements the high walls of the city.

There is Triptolemos subtle in mind and Diocles,

Polyenos and Eumolpus the blameless,

Dolichus and our own lordly father.

And all those who have wives to manage their households.

Of these not one at first sight would scorn

your appearance and turn you away from their homes.

They will receive you, for you are indeed godlike.

But if you wish, wait here, until we come to the house

of our father and tell Metaneira our deep-girt mother

all these things straight through, in case she might bid

you come to our house and not search after others’.

For her only son is now nursed in our well-built hall,

a late-born child, much prayed for and cherished.

If you might raise him to the threshold of youth,

any woman who saw you would feel envy at once,

such rewards for his rearing our mother will give you.’

Thus they spoke and she nodded her head. The girls

carried proudly bright jars filled with water and

swiftly they reached the great house of their father.

At once to their mother they told what they saw and heard.

She bade them go quickly to offer a boundless wage.

Just as hinds or heifers in the season of spring

bound through the meadow sated with fodder,

so they, lifting the folds of their shimmering robes,

darted down the hollow wagon-track, and their hair

danced on their shoulders like a crocus blossom.

They found the famed goddess near the road

just where they had left her. Then to the house

of their father they led her. She, grieved in her heart,

walked behind with veiled head. And her dark robe

swirled round the slender feet of the goddess.

They soon reached the house of god-cherished Celeos,

and went through the portico to the place where

their regal mother sat by the pillar of the close-fitted roof,

holding in her lap a child, the young offshoot. To her

they raced. But the goddess stepped on the threshold. Her head

reached the roof and she filled the doorway with divine light.

Reverence, awe, and pale fear seized Metaneira.

She gave up her chair and bade the goddess sit down.

But Demeter, bringer of the seasons and giver of rich gifts,

did not wish to be seated on the shining seat.

She waited resistant, her lovely eyes cast down,

until knowing Iambe set out a well-built stool

for her and cast over it a silvery fleece.

Seated there, the goddess drew the veil before her face.

For a long time she sat voiceless with grief on the stool

and responded to no one with word or gesture.

Unsmiling, tasting neither food nor drink,

she sat wasting with desire for her deep-girt daughter,

until knowing Iambe jested with her and

mocking with many a joke moved the holy goddess

to smile and laugh and keep a gracious heart –

Iambe, who later pleased her moods as well.

Metaneira offered a cup filled with honey-sweet wine,

but Demeter refused it. It was not right, she said,

for her to drink red wine; then she bid them mi barley

and water with soft mint and give her to drink.

Metaneira made and gave the drink to the goddess as she bid.

Almighty Demeter received it for the sake of the rite.

Well-girt Metaneira spoke first among them:

‘Hail, lady, for I suppose your parents are not lowborn,

but noble. Your eyes are marked by modesty

and grace, even as those of justice-dealing kings.

We mortals are forced, though it may hurt us, to bear

the gifts of the gods. For the yoke lies on our necks.

But now you have come here, all that’s mine will be yours.

Raise this child for me, whom the gods have provided

late-born and unexpected, much-prayed for by me.

If you raise him and he comes to the threshold of youth,

any woman who saw you would feel envy at once,

such rewards for his rearing would I give you.’

Rich-crowned Demeter addressed her in turn:

‘Hail also to you, lady, my the gods give you blessings.

Gladly will I embrace the child as you bid me.

I will raise him, nor do I expect a spell or the Undercutter

to harm him through the negligence of his nurse.

For I know a charm more cutting than the Woodcutter;

I know a strong safeguard against baneful witching.’

So speaking, she took the child to her fragrant breast

with her divine hands. And his mother was glad at heart.

Thus the splendid son of skilful Celeos, Demophon,

whom well-girt Metaneira bore, she nursed

in the great halls. And he grew like a divinity,

eating no food nor sucking [at a mother’s breast];

[For daily well-crowned divine] Demeter anointed

him with ambrosia like one born from a god

and breathed sweetly on him, held close to her breast.

At night, she would bury him like a brand in the fire’s might,

unknown to his parents. And great was their wonder

as he grew miraculously fast; he was like the gods.

She would have made him ageless and immortal,

if well-girt Metaneira had not in her folly

kept watch at night from her fragrant chamber

and spied. But she shrieked and struck both thighs

in fear for her child, much misled in her mind,

and in her grief she spoke winged words.

‘Demophon, my child, the stranger buries you

deep in the fire, causing me woe and bitter cares.’

Thus she spoke lamenting. The great goddess heard her.

In anger at her, bright-crowned Demeter snatched

from the flames with immortal hands the dear child

Metaneira had borne beyond hope in the halls and,

raging terribly at heart, cast him away from herself to the ground.

At the same time she addressed well-girt Metaneira:

‘Mortals are ignorant and foolish, unable to foresee

destiny, the good and the bad coming on them.

You are incurably misled by your folly.

Let the god’s oath, the implacable water of the Styx, be witness,

I would have made your child immortal and ageless

forever, I would have given him unfailing honour.

But now he cannot escape death and the death spirits.

Yet unfailing honour will forever be his, because

he lay on my knees and slept in my arms.

In due time as the years come round for him,

the sons of Eleusis will continue year after year

to wage war and dread combat against each other.

For I am honoured Demeter, the greatest

source of help and joy to mortals and immortals.

But now let all the people build me a great temple

with an altar beneath, under the sheer wall

of the city on the rising hill above Callichoron.

I myself will lay down the rites so that hereafter

performing due rites you may propitiate my spirit.’

Thu speaking, the goddess changed her size and appearance,

thrusting off old age. Beauty breathed about her and

from her sweet robes a delicious fragrance spread;

a light beamed far out from the goddess’ immortal skin,

and her golden hair flowed over her shoulders.

The well-built house flooded with radiance like lightning.

She left the halls. At once Metaneira’s knees buckled.

For a long time she remained voiceless, forgetting

to pick up her dear only son from the floor.

But his sisters heard his pitiful voice and

leapt from their well-spread beds. Then one took

the child in her arms and laid him to her breast.

Another lit the fire; a third rushed on delicate feet

to rouse her mother from her fragrant chamber.

Gathering about the gasping child, they bathed and

embraced him lovingly. Yet his heart was not comforted,

for lesser nurses and handmaidens held him now.

All night they tried to appease the dread goddess,

shaking with fear. But when dawn appeared,

they explained to wide-ruling Celeos exactly

what the bright-crowned goddess Demeter commanded.

Then he called to assembly his innumerable people

and bid them build for fair-tressed Demeter

a rich temple and an altar on the rising hill.

Attentive to his speech, they obeyed at once and did

as he prescribed. It grew as the goddess decreed.

But once they finished and ceased their toil,

each went off home. Then golden-haired Demeter

remained sitting apart from all the immortals,

wasting with desire for her deep-girt daughter.

For mortals she ordained a terrible and brutal year

on the deeply fertile earth. The ground released

no seed, for bright-crowned Demeter kept it buried.

In ain the oxen dragged many cured ploughs down

the furrows. In ain much white barley fell on the earth.

She would have destroyed the whole mortal race

by cruel famine and stolen the glorious honour of gifts

and sacrifices from those having homes on Olympus,

if Zeus had not seen and pondered their plight in his heart.

First he roused golden-winged Iris to summon

fair-tressed Demeter, so lovely in form.

Zeus spoke and Iris obeying the dark-clouded

son of Chronos, raced swiftly between heaven and earth.

She came to the great citadel of fragrant Eleusis

and found in her temple dark-robed Demeter.

Addressing her, she spoke winged words:

‘Demeter, Zeus, the father, with his unfailing knowledge

bids you rejoin the tribes of the immortal gods.

Go and let Zeus’ word not remain unfulfilled.’

Thus she implored, but Demeter’s heart was unmoved.

Then the father sent in turn all the blessed immortals;

one by one they kept coming and pleading

and offered her many glorious gifts and whatever

honours she might choose among the immortal gods.

Yet not one could bend the mind and thought

of the raging goddess, who harshly spurned their pleas.

Never, she said, would she mount up to fragrant

Olympus nor release the seed from the earth,

until she saw with her eyes her own fair-faced child.

When Zeus, heavy-thundering and mighty-voiced,

heard this, he sent down the Slayer of Argos to the Underworld

with his golden staff to wheedle Hades with soft words

and lead back holy Persephone from the misty gloom

into the light to join the gods so that her mother

might see with her eyes and desist from anger.

Hermes did not disobey. At once he left Olympus’ height

and plunged swiftly into the depths of the earth.

He met lord Hades inside his dwelling,

reclining on a bed with his shy spouse, strongly reluctant

through desire for her mother. [Still she, Demeter,

was brooding on revenge for the deeds of the blessed gods].

The strong Slayer of Argos stood near and spoke:

‘Dark-haired Hades, ruler of the dead, Father Zeus

bids me lead noble Persephone up from the Underworld

to join us, so that her mother might see her with her eyes

and cease from anger and dread wrath against the gods.

For she is devising a great scheme to destroy

the helpless race of mortals born on the earth,

burying the seed beneath the ground and obliterating

divine honours. Her anger is terrible, nor does she go

among the gods but sits aloof in her fragrant temple,

keeping to the rocky citadel of Eleusis.’

Thus he spoke and Hades, lord of the dead, smiled

with his brows, nor disobeyed king Zeus’ commands.

At once he urged thoughtful Persephone:

‘Go, Persephone, to the side of your dark-robed mother,

keeping the spirit and temper in your breast benign.

Do not be sad and angry beyond the rest;

in no way among immortals will I be an unsuitable spouse,

myself a brother of father Zeus. And when you are there,

you will have power over all that lies and moves,

and you will possess the greatest honours among the gods.

There will be punishment forevermore for those wrongdoers

who fail to appease your power with sacrifices

performing the proper rites and making due offerings.’

Thus he spoke and thoughtful Persephone rejoiced.

Eagerly she leapt up for joy. But he gave her to eat

a honey-sweet pomegranate seed, stealthily passing it

around her, lest she once more stay forever

by the side of revered Demeter of the dark robe.

The Hades commander-to-many yoked

his divine horses before the golden chariot.

She mounted the chariot and at her side the strong

Slayer of Argos took the reins and whip in his hands

and dashed from the halls. The horses flew eagerly;

swiftly they completed the long journey; not sea nor

river waters, not grassy glens nor mountain peaks

slowed the speed of the immortal horses,

slicing the deep air as they flew above these places.

He brought them to a halt where rich-crowned Demeter

waited before the fragrant temple. With one look she darted

like a maenad down a mountain shaded with woods.

On her side Persephone, [seeing] her mother’s [radiant face],

[left chariot and horses,] and leapt down to run

[and fall on her neck in a passionate embrace].

[While holding her dear child in her arms,] her [heart

suddenly sensed a trick. Fearful, she] drew back

from [her embrace and at once inquired:]

‘My child, tell me, you [did not taste] food [while below?]

Speak out [and hide nothing, so we both may know.]

[For if not], ascending [from miserable Hades],

you will dwell with me and your father, the

dark-clouded [son of Chronos]. honoured by all the gods.

But if [you tasted food], returning beneath [the earth,]

you will stay a third part of the seasons [each year],

but two parts with myself and the other immortals.

When the earth blooms in the spring with all kinds

of sweet flowers, then from the misty dark you will

rise again, a great marvel to gods and mortal men.

By what guile did the mighty Host-to-Many deceive you?’

Then radiant Persephone replied to her in turn:

‘I will tell you the whole truth exactly, Mother.

The Slayer of Argos came to bring fortunate news

from my father, the son of Chronos, and the other gods

and lead me from the Underworld so that seeing me with your eyes

you would desist from your anger and dread wrath

at the gods. Then I leapt up for joy, but he stealthily

put in my mouth a food honey-sweet, a pomegranate seed,

and compelled me against my will and by force to taste it.

For the rest – how seizing me by the shrewd plan of my father,

Chronos’ son, he carried me off into the earth’s depths –

I shall tell and elaborate all that you ask.

We were all in the beautiful meadow –

Leucippe; Phaino; Electra; and Ianthe;

Melite; Iache; Rhodeia; and Callirhoe;

Melibosis’ Tyche; and flower-faced Okyrhoe;

Chryseis; Ianeira; Acaste; Admete;

Rhodope; Plouto; and lovely Calypso;

Styx; Ourania; and fair Galaxaura; Pallas,

rouser of battles; and Artemis, sender of arrows –

playing and picking lovely flowers with our hands,

soft crocus mixed with irises and hyacinth,

rosebuds and lilies, a marvel to see, and the

narcissus that wide earth bore like a crocus.

As I joyously plucked it, the ground gaped from beneath,

and the mighty lord, Host-to-Many, rose from it

and carried me off against my will. And I cried out at the top of my voice.

I speak the whole truth, though I grieve to tell it.’

Then all day long, their minds at one, they soothed

each other’s heart and soul in many ways,

embracing fondly, and their spirits abandoned grief,

as they gave and received joy between them.

Hekate of the delicate veil drew near them

and often caressed the daughter of holy Demeter;

from that time this lady served her as chief attendant.

To them Zeus, heavy-thundering and mighty-voiced,

sent as mediator fair-tressed Rhea to summon

dark-robed Demeter to the tribes of gods; he promised

to give her what honours she might choose among the gods.

He agreed his daughter would spend one-third

of the revolving year in the misty dark and two-thirds

with her mother and the other immortals.

So he spoke and the goddess did not disobey his commands.

She darted swiftly down the peaks of Olympus

and arrived where the Rarian plain, once life-giving

udder of earth, now giving no life at all, stretched idle

and utterly leafless. For the white barley was hidden

by the designs of lovely-ankled Demeter. yet as spring came on,

the fields would soon ripple with long ears of grain;

and the rich furrows would grow heavy on the ground

with grain to be tied with bands into sheaves.

There she first alighted from the barren air.

Mother and daughter were glad to see each other

and rejoiced at heart. Rhea of the delicate veil then said:

‘Come, child, Zeus, heavy-thundering and mighty-voiced,

summons you to rejoin the tribes of the gods;

he has offered to give what honours you choose among them.

He agreed that his daughter would spend one-third

of the revolving year in the misty dark, and two-thirds

with her mother and the other immortals.

He guaranteed it would be so with a nod of his head.

So come, my child, obey me; do not rage overmuch

and forever at the dark-clouded son of Chronos.

Now make the grain grow fertile for humankind.’

So Rhea spoke, and rich-crowned Demeter did not disobey.

At once she sent forth fruit from the fertile fields

and the whole wide earth burgeoned with leaves

and flowers. She went to the kings who administer law,

Triptolemos and Diocles, drier of horses, mighty

Eumolpus and Celeos. leader of the people, and revealed

the conduct of her rites and taught her Mysteries to all of them,

holy rites that are not to be transgressed, nor pried into,

nor diulged. For a great awe of the gods stops the voice.

Blessed is the mortal on earth who has seen these rites,

but the uninitiated who has no share in the never

has the same lot once dread in the dreary darkness.

When the great goddess had founded all her rites,

the goddesses left for Olympus and the assembly of the other gods.

There they dwell by Zeus delighting-in-thunder, inspiring

awe and reverence. Highly blessed is the mortal

on earth whom they graciously favour with love.

For soon they will send to the hearth of his great house

Ploutos, the god giving abundance to mortals.

But come, you goddesses, dwelling in the town

of fragrant Eleusis, and sea-girt Paros, and rocky Antron,

revered Demeter, mighty giver of seasons and glorious gifts,

you and your very fair daughter Persephone,

for my song grant gladly a living that warms the heart.

And I shall remember you and a new song as well.

Claudian, The Rape of Proserpina (extracts of an incomplete

epic poem, trans. D. R. Slavitt)

….

O gods of the world of shadows, whom ghosts attend, to whom

mortality owes its all in a debt you wait to foreclose,

let me see those fields and meadows the Styx surrounds;

let me hear Phlegethon’s murmur and rush and feel the cold

spray of its rapids and eddies; and confide in me with your stories –

how with a torch the god of love overcame the god

of shadows, and tell the tale of his passion for Proserpina,

the innocent maiden he stole to trouble the land of the living

as Ceres, enraged, pursued her lost little girl. That passion,

that rape, and that long search transformed the lies of mortals

forever. No longer would acorns and such windfalls suffice us,

but now, with the secret of grains, and of cultivation, we moved

out of Dodona’s grove and into our sunlit fields,

away from the beasts and closer, at least a little, to gods.

Angry, Erebus’ lord blazed forth in complaint, to threaten

war with the gods of the air, if need be, to right this wrong:

that only he of the deities had no wife at his side,

none of the comforts and pleasures, none of the satisfactions

of the divine and even mortal husbands and fathers. No longer

would he suffer such unfairness, but summoning up the monsters

and the rest of his hellkite band he rules, and recruiting the Furies,

he bound them by oath to defy the imperious gods of the light

and the Thunder-god himself. …

But it was not fated to happen. The Fates themselves, in fear

for the world they care for, approached him, lowered their heads, and implored

with suppliants’ streaming tears and touched his knees with their hands.

Lachesis first, her hair a crazy tangle, called out

to the lord of the night, ‘Great ruler at whose command we spin,

and who knows the ends and beginnings of all things that live and die,

do not undo this work you have given into our keeping.

Do not abandon the sacred treaties you have with your brothers

on which the world’s survival depends. Do not make war

and loose the impious titans into the air. But go

to your brother Jove and ask. He will grant you that wife

you want and deserve.’ Pluto’s severe expression changed

at the words she spoke. His heart was eased and his anger soothed.

….

‘You, Mercury, alone are free to cross and recross these thresholds

of heaven and hell; I bid you to bear to my brother above

my greetings and my complaint, for if his domain is the air

and the earth, I am not without power here below. This darkness

bristles with weapons and strength. Let love, honour, and prudence

speak with a single voice to prompt him to pay me heed!

Let him consider our brother, Neptune, who lolls in the sea

with Amphitrite, his bride. With Juno, our sister, his wife,

Jove finds connubial comfort. We need not allude to the others,

those brief encounters whose issue is nieces and nephews of mine

I can hardy reckon. Long life to him and to his heirs forever!

But shall I not share these pleasures? Shall I not also have children

to offer me reverence and love here in the land of shadows?

I cannot accept so unfair or endure so unjust a portion

but must, for the sake of honour, redress this legitimate grievance

at whatever cost – if my words should fall on deaf ears, then trumpets

will sound through the chasms of hell to call forth attendant monsters

who shall reappear in the light to shroud the face of the sun

in eternal gloom. The world’s foundations will be overthrown

for all time and the cosmos itself be wholly undone.’

… The lord of Olympus heard [Mercury repeat the defiant words]

and considered this difficult question – a wife for Pluto? What woman,

noble or common, rich or poor, would consider exchanging

her portion of light and air to preside on that dark throne?

And yet … He could see, beyond his brother’s demands for justice,

and beyond the not insignificant threats, a fundamental

rightness that he could feel in his bones’ marrow – how love

and death reach out to each other in honour and need to sit

side by side at the end of each soul’s watch, where the efforts

of doing and saying at last are all unsaid and undone.

He thought at once of Ceres, whom men revere at her temple

at Enna. The goddess had prayed for a child and at last had conceived

and borne a daughter, and then her womb was exhausted: she knew

this infant, Proserpina, was her first and last and only

child. Any child is dear to a parent, but one like this

is precious beyond all measure. As a cow looks after its darling

wobbly-legged wide-eyed calf, so Ceres tended

her daughter, gazed upon her and watched her grow into girlhood

and ripen into maidenhood. She played as all girls do,

imagined herself a bride, a wife, and then a mother… but then,

in the midst of her innocent play, she would stop in sudden dread

of leaving her mother and home to go and lie with some stranger.

In the halls of her mother’s palace, suitors from far and wide

assembled: the halls resounded as loud masculine voices

of princes and even gods exchanged their playful banter.

The rival gods who appeared were the valiant Mars and Apollo,

the skilful bowman. The former offered her Rhodope’s heights,

and the latter’s counter-proposal was the town of Amyclae

and the island of Delos, and also his temple at Clarors where Manto’s

tears collected to form the miraculous lake. (On Olympus,

Mars’ and Apollo’s mothers, Juno and her old rival

Latona, bickered and argued, each claiming this daughter-in-law

as properly hers.) Ceres couldn’t or wouldn’t choose,

but recognising the possible dangers of indecision,

decided to send her daughter somewhere safe – to discourage

any hothead from thinking of kidnapping Proserpina.

….

[Ceres installs Proserpina at Enna in Sicily, blesses the place and departs to spend

time with her own mother, Cybele, on Mt. Ida]

….

‘This is the time,’ [Jove] instructed the goddess of love. ‘The mother

has left her alone and unguarded. Go down and do your mischief,

summon her out to the meadows at the delicate hour when dawn

has turned the whole world to a pleasantly rumpled bed.’

He sighed remembering the beds he had rumpled. ‘Why should the lord

of darkness not share in your bounties and blessings? Your power

extends even there, to the depths of his dismal realm where cold

and unfeeling hearts grow tender and burn from your arrows’ wounds.’

….

[Venus, Minerva and Diana set out to Sicily and find Proserpina working on her

needlepoint – a depiction of the world and its creation]

…All this she put in her representation

of how things are in the world. She included the nether kingdom

where her uncle ruled over wistful or tormented souls, and her tears

welled up for their sad condition and the fate that waits for us all.

…

Proserpina ventured forth … Her mother had warned her not to,

but who can oppose what the stern Fates have already decreed?

As she opens the door to go out, its hinges shriek shrill warnings,

to which the volcano rumbles from out of its depths an endorsement,

but she seems deaf as the doorpost.

….

Her mother’s pride and joy, who is shortly to be the occasion

of bitterest grief, is walking along on the grass she takes

for granted as safe – as any child ought to be able

to do beneath a sky whose gentle blue she never

suspected or thought deceptive.

….

[Pluto arrives]

The nymphs scatter in flight, put to rout. Do any

see the chariot bearing down, the god leaning over

to snatch their companion up in the crook of his arm? …

…What can they do to defy

the power of their dark uncle? Virgins both, they feel for their friend,

a virgin and therefore a sister. Each of them thinks of herself

in the arms of some ravishing monster, struggling, breathless, helpless,

and wishing for death while knowing that worse is about to happen.

….

[Minerva speaks:]

…‘How do you dare

intrude into the ream of your brothers? Return to your proper

place, and find there the wife you are seeking. To share your rule

in darkness, you shouldn’t require such beauty or youth.’

…She froze as the understanding

suddenly dawned in her mind that Jove had agreed to the union.

Proserpina’s father, he signalled consent to the match to which no

lesser god or mortal could now make further objection.

After the flash of lightning, the crash of thunder confirmed

the judgement of fate and the gods in an ear-splitting amen.

Minerva stepped aside. Diana too put down

her weapon and called to her friend. If she could not say adieu,

at least she could bid her farewell. ‘We must yield to greater power.

What our father commands we must all obey, albeit in sorrow,

mourning that you are thus betrayed to darkness and silence,

never more to behold your sisters or play in these fields

of innocence and delight. e who remain here shall weep,

think of you and recall the pleasures we shared together –

for the gods have sundered heaven and earth and so mocked your trust;

of your child-like faith in the world’s benevolence nothing remains,

and the woods will be darker now, the pathways along the cliffs

more fraught with peril, and beasts we chase more savage and fierce.

My moon will not shine so bright, and my brother’s fiery son

will be sicklied over; his Delphic shrine will turn thick-tongued…’

There might have been more, but the lord of Hades lashed his horses

that hurtled by; the girl in his grip in that flying car

was swept away, her hair flying out behind in the slipstream.

She waved her arms for help, or in protest and lamentation

and cried in ain to the gods in heaven to come to her rescue:

‘Oh father, sae me! or else send down your thunderbolt

to undo this dreadful thing: obliterate this wrong.

Destroy if you must both crime and victim, but do not leave me,

do not abandon me so. How can a father’s love

for a daughter dwindle and dry like a stream in the summer’s meanness?

What have I done to deserve such anger? Where was my sin?

I look to you for love, or at least for an even-handed

justice, but you desert me, and I am bereft and despair.

Other girls may be seized, carried away and ravished,

but still they are left alive to heal in the light of the sky.

I shall be robbed of each of the joys of life on earth

and thrust into darkest Hell, having done nothing, nothing…’

Words failed, but her heart and throat kept on with a pure

keening in which the cold winds joined in crazed agreement.

The flowers, she thought, had betrayed her. All those innocuous blossoms

the goddess had offered – as bait! She felt a pang of remorse

for not having obeyed her mother who, now it turned out,

was no over-protective parent but properly wary

of bad things that can happen no maiden would ever imagine.

At the thought of her mother she wailed the louder and then called out

in desperation: ‘Mother, wherever you are, oh, mother,

hear me, find me, forgive me. Come to me and sae me.’

But how could she hope her mother could hear, way off at the end

of the earth in those Phrygian mountains where cultists dance in their frenzies

and cut their flesh with knives as a sign of divine madness?

But someone heard her. Closer at hand, stern Pluto was moved

by her fear, her grief, and her beauty. He wiped away her tears

with the hem of his rough cloak and, as well as he could, assured her,

‘Stop your crying, child. You shall rule with me as queen

of the realm below. I am not after all so bad a husband,

but a son of Saturn, whose order the cosmos obeys, and the brother

of mighty Jove and Neptune. You fear my kingdom, I know,

but calm yourself. We too have stars, meadows, and flowers

that never fade but bloom forever and send their delicate

fragrances into the ever-temperate air. I promise

mysterious wonders and simple pleasures. The Champs Elysees (Elysian Fields)

await to delight you, brighten your life, admire, adore you.

I promise that I shall try to make you happy. You leave

the world of the living behind, but all that is mortal will come

at last to present itself to us and bow before us.

you shall be queen of the autumn! A tree, which shall be your tree,

produces leaves and branches and fruit of solid gold!

Beneath that tree you shall sit, or better say, preside,

reaping its precious harvest as, barefoot, the kings of the world

march before you in fear to hear you pronounce your judgements

on the deeds of their just completed lies, and what their rewards

or punishments ought to be. The three fates will be ladies

in waiting attending upon you, and Lethe shall flow to your wish.’

Intrigued? Horrified? Pleased? Most likely, she was struck dumb,

by this bizarrerie, the noise of the horses’ hoofs,

and the quiet throng of souls that collected about the cart

to welcome their master. Thick as leaves on a hill in autumn

after a wind has passed to shake the boughs, as many

as waves on the sea, or grains of sand in the desert wastes,

the souls of men and women hastened on noiseless feet

for a glimpse of the bride, eager to pay their respects and homage

to Pluto’s queen. Their stern master is smiling broadly,

which is most unlike him: they stare from him to her and back,

and are happy but ill at ease, unwilling to trust, or unable,

this unaccustomed mollification.

…. [household servants] bedeck

the halls, arches, and doorways with tapestries, floral hangings,

and all the appropriate symbols for such an occasion of …joy?

What else would one think to call it? The maidens and matrons are gathered

to sere, to share her delight, to welcome her, to braid

her beautiful hair and then place on her head the traditional veil.

It’s a festival, after all, a great occasion – the ghosts

in a moment of rare recreation perform a series of dances,

elaborate figures they weave in the courtyards and halls.

The disembodied wraiths, the Manes, sit down to the banquet

with delicate garlands that wreath their all but substantial brows,

and the usual silence gives way to the faint humming of tunes

recalled from another life – humming, or even singing,

with the various voices harmonising in rare concord.

….

… On earth

nobody dies, no one is killed, neither parent nor child.

Nowhere in all the world does the glare of a funeral pyre

highlight grotesque contortions of grief. Sailors come home

and soldiers return to their sweethearts, every one sage and alive

in the countryside and the towns. Charon has no one to ferry

but festoons himself and his skiff and sings like a gondolier.

The evening star is ablaze and Night in her gorgeous raiment

richly bejewelled is the matron of honour who leads the bride

into the vaulted chamber and touches the nuptial bed

that awaits the pair. She recites the blessings to consecrate

their union and also the dawn of the new age each marriage

ought to portend but this one truly does, a hope

and fresh beginning. The numberless shades have assembled outside

and raise their voices to sing. The palace corridors ring

to the strains of their stately anthem: ‘Proserpina, our queen,

and Pluto our lord and master, brother and son-in-law

of Olympian Jove who carries the thunderbolts, you join

two souls intertwined to one in sleep and in waking,

to the end of time and beyond. May your union be rich and fruitful,

with offspring, goddesses, gods, yet to be born, the heirs

of Ceres and Jove that all in Nature in awe awaits..’

….

[Demeter after a nightmare flies to Sicily]

…There, below, she espies

the island, the castle walls… But the gate is ajar, the courtyard

deserted, the doors wide open. Inside, the hallways are empty.

Where are the guards? The servants? She tears from her head the wreath

of grain and shudders and moans. She rends her clothing. She cannot

speak or even breathe, but staggers from room to room:

each doorway’s empty vista assaults, reproaches, accuses,

condemns… She remembers her dream and the arduous effort of every

step she took, and takes. She feels it again in her calves

and ankles. She reaches her daughter’s bedroom. The little loom

on which the girl had been working waits in the corner, the weaving

a terrible thing to behold left off that way. But worse,

Ceres sees above it the web of a spider, the only

sign in the desolate room of weaving, work, or life.

Its fragile weigh is too much: she draws a painful breath,

but will not weep. She will not. She kisses the frame of the loom

her daughter’s hand had touched. She touches the delicate threads

as if they were strands of her daughter’s beautiful hair. The spindle

she recently used hangs down like a dead thing. Ceres sits,

or in fact collapses, upon her daughter’s now empty bed,

touches the pillow that often touched the young girl’s cheeks,

and strokes it as if it were flesh. She is not mad but wishes

madness might come to bring her relief, as it can for desperate.

…. [Electra, Proserpina’s nurse, tells Ceres about the goddesses’ arrival and tempting

out of Proserpina and its disastrous result – Proserpina’s disappearance. None of the

gods will tell Ceres what happened…]

…. ‘very well! Damn you all! I will search

to the ends of the earth to find her, will scour the hidden places

from the furthest shores of the Red Sea to the frozen Alpine crags.

I will ignore extremes of heat and cold, and pursue

day and night through dust and mud in cities and towns,

meadows, deserts, and forests, while you look down and laugh

in scorn … But I will succeed. I swear that I shall find her

if it takes me the rest of eternity. Ceres is not yet vanquished!’

… [Ceres cuts down trees and lights them in pools of lava to light her search]…

…she sets out on her journey, moaning aloud, addressing

her daughter – but knowing perfectly well that no one can hear:

‘These are not the torches I dreamt I would one day carry.

I had thought – as every mother does – of the wedding torch

I’d hold to light your way from a happy nuptial feast

to the bridal chamber and bed and the start of a decent life.

Look at me now! A garish vision of rage and woe,

with distorted shadows I cast behind me of how the fates

can sport even with the gods, turning the commonplace

into a sudden horror. What men must feel, I feel –

puzzled and hurt that my brief moments of peace and contentment

should have so piqued their envy, or invited such brutal redress.

Those peasant women who never smile, lest the gods impose

a tax on their miniscule pleasures, are right after all. I admitted

my joy and pride in my daughter, my only child, but enough

to satisfy whatever maternal dreams I’d had.

With you I was truly content, the equal even of Juno;

now I am less than the least human beggar or outcast.

My case is worse, for mortals’ suffering sooner or later

comes to an end, but mine will go on and on, forever.

I rage against Jupiter’s will, but still a part of me knows

it wasn’t his doing but mine, my own mistake, my folly

leaving you here while I was gallivanting elsewhere,

in the train of the mother goddess. I knew there was danger: I took

precautions, but not enough. I should never have gone in the first place.

It’s me the fates want to punish: they are only using you,

knowing how much worse your pains are for me to endure.

‘Where have you gone, my baby? Where are you hidden? In what

part of the earth or sky or sea cave? Where shall I look?

Someone must help me, pity me, or pity you, who have done

nothing, nothing at all! But I shall do what it takes

to find some trace, some clue, some faint hoofprint or rut

of those wheels, a bent grass blade, a broken twig. I will comb

the terrain, with unflagging persistence, and, sooner or later, discover

some hint of who it was, god, demigod or mortal,

and hate shall bear me up, for I shall imagine …HER!

Dione, Venus’ mother, reduced to this sorry condition.

She deserves this, not me. And the day will arrive when my labours

succeed, or luck, or a dream that will speak to me and give me

my beautiful daughter, happy and healthy, once more in my arms.’

You might also like

- Hecate Witchcraft, Death & Nocturnal MagicDocument218 pagesHecate Witchcraft, Death & Nocturnal MagicJesse92% (13)

- Pagan HolidaysDocument7 pagesPagan HolidaysSonofMan100% (3)

- A Complete List of Greek Underworld GodsDocument3 pagesA Complete List of Greek Underworld GodsTimothy James M. Madrid100% (1)

- Euripides ElectraDocument45 pagesEuripides ElectraEleanor OKellNo ratings yet

- Who Is The Black MadonnaDocument6 pagesWho Is The Black MadonnaTalon Bloodrayn100% (2)

- The Secret History of The Triple Goddess, Part 1Document17 pagesThe Secret History of The Triple Goddess, Part 1Lorac ArievlisNo ratings yet

- Greek God of WarDocument4 pagesGreek God of WarMher BuenaflorNo ratings yet

- Demeter and PersephoneDocument5 pagesDemeter and PersephoneSantiago Iregui RuizNo ratings yet

- Apollo Is A Greek God With ManyDocument4 pagesApollo Is A Greek God With ManyCatherine Magpantay-MansiaNo ratings yet

- Flood Stories From Around The World Mark IsaakDocument99 pagesFlood Stories From Around The World Mark IsaakDaniel SultanNo ratings yet

- HekatesiaDocument8 pagesHekatesiaKa Jose100% (1)

- Satis (Goddess)Document4 pagesSatis (Goddess)Geraldo CostaNo ratings yet

- 1988 The Eleusinian Mysteries of Demeter and Persephone Fertility, Sexuality, and RebirthDocument29 pages1988 The Eleusinian Mysteries of Demeter and Persephone Fertility, Sexuality, and RebirthJorge Hantar Touma LazoNo ratings yet

- Seth as a Divine TricksterDocument4 pagesSeth as a Divine TricksterDaniel Arpagaus100% (1)

- The Chthonic Gods of Greek ReligionDocument20 pagesThe Chthonic Gods of Greek ReligionJorge Carrillo100% (1)

- Carl Jung - Psychological Aspects of The KoreDocument5 pagesCarl Jung - Psychological Aspects of The KorekarinadapariaNo ratings yet

- Some Cults of Greek Goddesses and Female Daemons of Oriental Origin PDFDocument591 pagesSome Cults of Greek Goddesses and Female Daemons of Oriental Origin PDFJeffrey Robbins100% (1)

- Olympian GODS and GoddesSesDocument4 pagesOlympian GODS and GoddesSes이고양No ratings yet

- The Sorcery of Hekate - Strategic SorceryDocument5 pagesThe Sorcery of Hekate - Strategic SorceryJohn RootNo ratings yet

- Tales of Anatolia From Hekatesia To AphrDocument18 pagesTales of Anatolia From Hekatesia To AphrSimonida Mona VulićNo ratings yet

- Societe D'etudes Latines de BruxellesDocument11 pagesSociete D'etudes Latines de BruxellesMarcela RistortoNo ratings yet

- Circe: ScriptDocument2 pagesCirce: ScriptEleanor OKell0% (2)

- Eng 312: Mythology and Folklore Characters of Greek MythologyDocument8 pagesEng 312: Mythology and Folklore Characters of Greek Mythologyvinayak vatsNo ratings yet

- Persephone, Psyche, and The Mother-Maiden Archetype PDFDocument7 pagesPersephone, Psyche, and The Mother-Maiden Archetype PDFDylan ThomasNo ratings yet

- Dianic Wicca Research ProjectDocument6 pagesDianic Wicca Research Projectmellatrix100% (2)

- Nyx's ChildrenDocument2 pagesNyx's ChildrenKim CanichNo ratings yet

- Hermes the Thief: Remembering Norman O. BrownDocument25 pagesHermes the Thief: Remembering Norman O. Brown4453poetNo ratings yet

- Medusa Other SideDocument19 pagesMedusa Other SideCaesarRRZNo ratings yet

- The Many Faces of Hecate: Epithets of the Greek GoddessDocument1 pageThe Many Faces of Hecate: Epithets of the Greek GoddessBranislav Djordjevic100% (1)

- Circe and PenelopeDocument14 pagesCirce and Penelopepierrette1No ratings yet

- IS Conference Theurgy Ritual DynamicsDocument5 pagesIS Conference Theurgy Ritual Dynamicsblavska100% (1)

- CUPID and PSYCHE - Mythological AnalysisDocument28 pagesCUPID and PSYCHE - Mythological Analysisrolz986100% (2)

- To Lock of EleusisDocument37 pagesTo Lock of EleusisTeatro RelacionalNo ratings yet

- About Melinoe and Hekate Trimorphis in TDocument7 pagesAbout Melinoe and Hekate Trimorphis in Ttroy thomsonNo ratings yet

- Hekate: Theoi Project - Greek MythologyDocument9 pagesHekate: Theoi Project - Greek MythologyLele Potrif0% (1)

- We Are Not The First by Andrew Tomas 1972 - OCRDocument240 pagesWe Are Not The First by Andrew Tomas 1972 - OCRBS13No ratings yet

- Module in Eng 11Document9 pagesModule in Eng 11Gretchen Tajaran100% (1)

- Goddess of the Harvest, Agriculture, Fertility and Sacred LawDocument19 pagesGoddess of the Harvest, Agriculture, Fertility and Sacred LawmagusradislavNo ratings yet

- Madea's Ritual of the Mandrake CharmDocument1 pageMadea's Ritual of the Mandrake CharmBrian SimmonsNo ratings yet

- Artemis-Hekate A. Artemis and Hekate: Ek I, 11 Eknttti) 6A.ODocument2 pagesArtemis-Hekate A. Artemis and Hekate: Ek I, 11 Eknttti) 6A.OIan H GladwinNo ratings yet

- ? Hades - Greek God of The UnderworldDocument3 pages? Hades - Greek God of The UnderworldFranchezka ArnejoNo ratings yet

- HekateDocument7 pagesHekateSelena Rumba100% (1)

- ANCIENT GREECE'S CREATION MYTHDocument37 pagesANCIENT GREECE'S CREATION MYTHmayNo ratings yet

- Athenian Festival CalendarDocument13 pagesAthenian Festival CalendarBrian SimmonsNo ratings yet

- Ares: The God of WaDocument3 pagesAres: The God of WajafjfsjsajfNo ratings yet

- The Lesser Mysteries of EleusisDocument5 pagesThe Lesser Mysteries of EleusisMónica GobbinNo ratings yet

- The Black Rite of HekateDocument6 pagesThe Black Rite of HekateTurgut TiftikNo ratings yet

- A Portrait of HecateDocument19 pagesA Portrait of HecateDenisa MateiNo ratings yet

- The Two Great Gods of Earth: Demeter and DionysusDocument23 pagesThe Two Great Gods of Earth: Demeter and DionysusNeiNo ratings yet

- The Two Great Gods of Earth: Demeter and DionysusDocument23 pagesThe Two Great Gods of Earth: Demeter and DionysusNeiNo ratings yet

- PythiaDocument13 pagesPythiaEneaGjonajNo ratings yet

- The Sibyl of CumaeDocument6 pagesThe Sibyl of CumaeEleanor OKellNo ratings yet

- Hephaestus - GodDocument11 pagesHephaestus - GodAvocadoraNo ratings yet

- Antony - Funeral OrationDocument3 pagesAntony - Funeral OrationEleanor OKell100% (1)

- Reconstructing The Sacred Experience at The HekateDocument17 pagesReconstructing The Sacred Experience at The HekateDenisa MateiNo ratings yet

- AidonaeaDocument15 pagesAidonaeaLjubica NedicNo ratings yet

- The Concept, Origins and Types of FestivalsDocument33 pagesThe Concept, Origins and Types of FestivalsRicardo MuñozNo ratings yet

- Persephone and The PomegranateDocument3 pagesPersephone and The PomegranateLíviaNo ratings yet

- Report: HephaestusDocument16 pagesReport: HephaestusMichelle Anne Atabay100% (1)

- The Abduction of PersephoneDocument3 pagesThe Abduction of PersephonePrinceroy DavisNo ratings yet

- Dionysos Mystes by G. Rizzo Zagreus, Studi Sull' Orfismo by v. MacchioroDocument6 pagesDionysos Mystes by G. Rizzo Zagreus, Studi Sull' Orfismo by v. MacchioroSandra Torres MartínezNo ratings yet

- Greek Athletic Sports and Festivals: With the Extract 'Classical Games' by Francis StorrFrom EverandGreek Athletic Sports and Festivals: With the Extract 'Classical Games' by Francis StorrNo ratings yet

- DemeterDocument1 pageDemeterLemon XhinetteNo ratings yet

- Comparing The Themes in The Epic of Gilgamesh and The Hebrew BibleDocument4 pagesComparing The Themes in The Epic of Gilgamesh and The Hebrew BibleBrian RwigiNo ratings yet

- HeraDocument12 pagesHeraJacquelin Santana100% (1)

- Edwards, C. M. (1986) - The Running Maiden From Eleusis and The Early Classical Image of Hekate. American Journal of Archaeology, 90 (3), 307.Document17 pagesEdwards, C. M. (1986) - The Running Maiden From Eleusis and The Early Classical Image of Hekate. American Journal of Archaeology, 90 (3), 307.Denisa MateiNo ratings yet

- The Muses and Three Graces of Greek MythologyDocument3 pagesThe Muses and Three Graces of Greek Mythologydeus_primus100% (1)

- Literary ArchetypesDocument8 pagesLiterary ArchetypesRaine CarrawayNo ratings yet

- Apollo: by Ron LeadbetterDocument61 pagesApollo: by Ron LeadbetterAshvin WaghmareNo ratings yet

- Hades, Greek God of The UnderworldDocument6 pagesHades, Greek God of The UnderworldyourlifelineNo ratings yet

- Info AconiteDocument8 pagesInfo AconiteAndreea Cúrea100% (1)

- Leaflet - Routes and MapDocument2 pagesLeaflet - Routes and MapEleanor OKellNo ratings yet

- Euripides OrestesDocument59 pagesEuripides OrestesEleanor OKellNo ratings yet

- Egyptian Info PointsDocument6 pagesEgyptian Info PointsEleanor OKellNo ratings yet

- Greek and Roman Info PointsDocument9 pagesGreek and Roman Info PointsEleanor OKellNo ratings yet

- AeneasDocument3 pagesAeneasEleanor OKellNo ratings yet

- CharonDocument11 pagesCharonEleanor OKellNo ratings yet

- Horus and Lector PriestDocument7 pagesHorus and Lector PriestEleanor OKell100% (1)

- OrpheusDocument2 pagesOrpheusEleanor OKellNo ratings yet

- OrpheusDocument2 pagesOrpheusEleanor OKellNo ratings yet

- The Sirens in Greek MythologyDocument4 pagesThe Sirens in Greek MythologyQuan NguyenNo ratings yet

- Hades and PersephoneDocument11 pagesHades and PersephoneMarvin RinonNo ratings yet

- Symbols RitualsDocument22 pagesSymbols RitualsMartina BilbaoNo ratings yet

- List of Greek Gods and GoddessesDocument3 pagesList of Greek Gods and GoddessesAna Leah ContridasNo ratings yet

- PDF Version of DemeterDocument8 pagesPDF Version of Demeterpierrette1No ratings yet

- Types of MythDocument3 pagesTypes of MythRejelle CosteloNo ratings yet

- 2) Literary CriticismDocument26 pages2) Literary CriticismArtchie BurcaNo ratings yet

- Mythos I - The Shaping of Our Mythic Tradition - 05 - The Mystical LifeDocument36 pagesMythos I - The Shaping of Our Mythic Tradition - 05 - The Mystical LifexlspnnvxdfNo ratings yet

- Greek MythologyDocument2 pagesGreek MythologyMerchel JavienNo ratings yet

- Four Functions of MythDocument2 pagesFour Functions of MythJoshua Benedict CoNo ratings yet

- Literature Reader: Class-ViDocument14 pagesLiterature Reader: Class-ViIndrajit GhoshNo ratings yet

- Narrative Text SamplesDocument21 pagesNarrative Text SamplesDwi Rahmiati HasyarNo ratings yet

- Demeter and Persephone by Anne Terry WhiteDocument4 pagesDemeter and Persephone by Anne Terry WhiteDerek David Rouch33% (3)

- Feminist ViewDocument22 pagesFeminist ViewAhmed EidNo ratings yet

- Greek Gods and GoddessesDocument4 pagesGreek Gods and Goddessesdanes cheeseballsNo ratings yet

- Zeus Turns Into Bill to Impress EuropaDocument89 pagesZeus Turns Into Bill to Impress EuropaMadock BikusNo ratings yet

- Main Gods I OlympiansDocument76 pagesMain Gods I OlympiansMary Cesleigh BlancoNo ratings yet

- Classical Gods and Myths ExplainedDocument15 pagesClassical Gods and Myths ExplainedYuki IshidaNo ratings yet

- Greek Mythology Midterm ReviewDocument8 pagesGreek Mythology Midterm ReviewFlonja ShytiNo ratings yet