Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Encoding and Decoding

Encoding and Decoding

Uploaded by

RFrearsonOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Encoding and Decoding

Encoding and Decoding

Uploaded by

RFrearsonCopyright:

Available Formats

Y 2 ENCODTNG AND DECODING

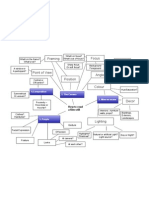

l<ey issues in audience studies concerns the relationship between producer, text and audience. In many ways this equation is about a balance of power: assessing the extent to which audiences are influenced and swayed by media texts, and to what extent they appropriate them in ways quite different to the producers' intentions.

0ne of the

programme as

discourse

a/'meaningful'

encoding

meanrng

\

decoding.

structures

meaning structures 2

frameworks of knowledge relations of production technical infrastructure

frameworks

:1_l!eY99e:

relations of

PI-"9Tl19!

technical infrastructure

Extract 29

Source: S.

Hall, 'Encoding/Decoding', in S. Hall et al. (eds), Culture, Media, Language, Hutchinson, I 980, p. I 30

MEDI.A Si.UDlES: THE ESSENTIAL RESOURCE

0ne of the earliest explorations of this relationship comes in Stuart Hall's Encoding/ Decoding model. In the diagram reproduced above, he represents the two sides: encoding, which is the domain of the producer, and decoding, the domain of the audience. The process of communicating a message requires that it be encoded in such a way that the receiver of the message is able to decode it. For example, a televisual message is encoded through the use of camera technology, transmitted as a signal and then decoded using a television set. If you do not have a television set, then you don't have the means to understand or decode the televisual message. Examine the symmetry between the two sides in the diagram above. Both encoding and decoding tal<e place within the similar contexts, which ultimately provide the means by which the message can be transmitted and received. 0ne reason that the encoded and decoded messages may not be the same is the capacity of the audience to vary its response to media messages. Hall identified three possible types of response that an audience might make to a media message, as Bell, Joyce and Rivers also point out in the extract below.

The encoding/decoding model put forward by Stuart Hall and David Morley centred on the idea that audiences vary in their response to media messages. This is because they are influenced by their social position, gender, age, ethnicity, occupation, experience and beliefs as well as where they are and what they are doing when they receive a message. In this model, media texts are seen to be encoded in such a way as to present a preferred reading to the audience but the audience does not necessarily accept that preferred reading. Hall categorised three kinds of audience response.

I r I

Dominant - the audience agree with the dominant values expressed within the preferred reading of the text Negotiated - the audience generally agree with the dominant values expressed within the preferred reading but they may disagree with certain aspects according to their social background Oppositional - the audience disagree with dominant values expressed within the preferred reading of the text

A. Bell, M. Joyce and D. Rivers, Advanced Media Studies, Hodder & Stoughton, 1999, p. 2l

0ne concept that has been challenged subsequently by theorists is the notion of Hall's 'preferred reading'. This refers to the way the encoder would prefer the audience to interpret a media message, above all other possible readings. However, it could be argued

that some texts are deliberately created to remain open to interpretation. The films of David Lynch/ such as Lost Highway or Mulholland Drive, are examples of texts that deliberately leave it up to the audience to mal<e their own individual readings.

A theorist who developed the ideas behind Hall's Encoding and Decoding model was John Fiske. He explained the distinction between the two sides of the model as an opposition

IVI

EDIA.AUDIENCES

between the 'power bloc' of a dominant cultural, political and social order and'the people'. The power bloc produces mass products that the people change by their resistance to them. As Nicl< Stevenson explains in his essay, 'Critical Perspectives with Audience Research': 'popular culture is made by the people, not produced by the cultural industry'.

From this perspective, the audience is empowered in a way that might not be readily

observed. Stevenson goes on to cite Fisl<e's use of Madonna's music to exemplify the way in which'the act of consumption always entails the production of meaning'.

The circulation of meaning requires us to study three levels of textuality while teasing out the specific relations between them. First there are the cultural forms that are produced along with the new Madonna album to create the idea of a medla event. These can include concerts, books, posters and videos. At the next level, there is a variety of media talk in popular magazines and newspapers,

television pop programmes and radio shows all offering a variety of critical commentary upon Madonna. The flnal level of textuality, the one that Fiske claims to be most attentive to, involves the ways in which Madonna becomes part of our everyday life. According to Fiske, Madonna's career was launched by a rockvideo of an early song'Lucky Star'. She became established in 1985 as a cultural icon through a series of successful LPs and singles, the film Desperateltl Seekinq Sasan, nude shots that appeared in Penthouse and Plaqboy, as well as the

successful marketing of a certain 'look'. Fiske argues that Madonna symbolically plays with traditional male-dominated stereotypes of the virgin and the whore in order to subtly subvert patriarchal meanings. That is, the textuality of Madonna ideologically destabilises traditional representations of women. Fiske accounts for Madonna's success by arguing that she is an open or writerly text rather than a closed readerly one. In this way, Madonna is able to challenge her fans to reinvent their own sexual identities out of the cultural resources that she and patriarchal capitalism provides. Hence Madonna as a text is polysemic, patriarchal and sceptical. In the final analysis, Madonna is not popular because she is promoted by the culture industry, but because her attempts to forge her own identity within a male-defined culture have a certain relevance for her fans.

N. Stevenson, 'Critical Perspectives within Audience Research' in T. O'Sullivan and Y. lewkes (eds), Tlie Media Studies Rea.ler, Arnold , 1997 , p. 235

Choose a more u,p,'to-dlte e xar:npls :sf 6:product of mass culture that you think has been appropr.iated by peo,ple as 'alcultural rresoutce'. Explain how you,think that

audiences may have used it differentlyfrom the way the producers intended.

MEDI:A ST.UDlES: THE ESSENTlAL RESOURCE

You might also like

- Open Closed TextsDocument6 pagesOpen Closed TextsRedAlert06No ratings yet

- Constructing The Popular Cultural Production and ConsumptionDocument16 pagesConstructing The Popular Cultural Production and Consumptionlistyaayu89No ratings yet

- Media Discourse PDFDocument209 pagesMedia Discourse PDFCyth Rhuf92% (12)

- Essays in Celebrity Culture: Stars and StylesFrom EverandEssays in Celebrity Culture: Stars and StylesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Active AudienceDocument38 pagesActive AudienceAgustine_Trily_7417No ratings yet

- Crazy About You - Reflections On The Meanings of Contemporary Teen Pop MusicDocument15 pagesCrazy About You - Reflections On The Meanings of Contemporary Teen Pop MusicAkhmad Alfan RahadiNo ratings yet

- Answer No 4Document4 pagesAnswer No 4Anamta KhanNo ratings yet

- Iglesia Assignment2 PDFDocument4 pagesIglesia Assignment2 PDFAriane Dale IglesiaNo ratings yet

- Stuar Hall and Reception TheoryDocument2 pagesStuar Hall and Reception Theoryrmelshn.1No ratings yet

- Shuker, R., Understanding Popular Music, Key Concepts, Routledge, London, 2001 (pp.1-7)Document8 pagesShuker, R., Understanding Popular Music, Key Concepts, Routledge, London, 2001 (pp.1-7)benjaminpnolanNo ratings yet

- Popular Culture and Critical Media Literacy in Adult Education: Theory and PracticeDocument9 pagesPopular Culture and Critical Media Literacy in Adult Education: Theory and PracticeLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Theories of An Active Audience-1Document14 pagesTheories of An Active Audience-1Shadow Knight 022No ratings yet

- Audience IdeasDocument2 pagesAudience IdeasRFrearsonNo ratings yet

- Harrington Popular Culture Chapter 001Document16 pagesHarrington Popular Culture Chapter 001Cristina CherryNo ratings yet

- Module 18: Audience/Reception StudiesDocument16 pagesModule 18: Audience/Reception StudiesOluwaseun AkapoNo ratings yet

- Kloet VanZoonen DevereuxDocument20 pagesKloet VanZoonen DevereuxElusinosNo ratings yet

- Reception Theory PhillipsDocument13 pagesReception Theory PhillipsLori WitzelNo ratings yet

- Chapter3 PDFDocument77 pagesChapter3 PDFSushobhit HarshNo ratings yet

- PhilPopCulture Module 1Document5 pagesPhilPopCulture Module 1gray grayNo ratings yet

- Comm Analysis PaperDocument12 pagesComm Analysis Paperapi-340960893No ratings yet

- Media and GlobalizationDocument43 pagesMedia and GlobalizationjerimieNo ratings yet

- By of by of Be: Notes For To A Discussion of Popular Culture I IDocument8 pagesBy of by of Be: Notes For To A Discussion of Popular Culture I ILata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Anthropology Meets Something!!Document2 pagesAnthropology Meets Something!!Rifqi KhairulNo ratings yet

- Toward A Cultural Studies That Is Critica1Document2 pagesToward A Cultural Studies That Is Critica1Darvi Earl MelanoNo ratings yet

- Media and GlobalizationDocument41 pagesMedia and GlobalizationMariz Bañares Denaga75% (4)

- Tan, Understanding The "Structure" and "Agency" Debate in The Social Sciences (& FULL JOURNAL)Document52 pagesTan, Understanding The "Structure" and "Agency" Debate in The Social Sciences (& FULL JOURNAL)hoorieNo ratings yet

- Popular Culture and GenderDocument5 pagesPopular Culture and GenderelizabethpelaezNo ratings yet

- Commercial CultureDocument9 pagesCommercial CultureSaurav DattaNo ratings yet

- Children and Media A Cultural Studies ApproachDocument29 pagesChildren and Media A Cultural Studies ApproachMatheus VelasquesNo ratings yet

- Weekn 10 Contemporary WorldDocument7 pagesWeekn 10 Contemporary WorldMona CampanerNo ratings yet

- Weight Making A Monkey Look Good The Case For Consumer Ethics of Entertainment MediaDocument32 pagesWeight Making A Monkey Look Good The Case For Consumer Ethics of Entertainment MediajoeNo ratings yet

- Advertising and Design: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on a Cultural FieldFrom EverandAdvertising and Design: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on a Cultural FieldBeate FlathNo ratings yet

- 1 Digital Theory: Theorizing New Media: Glen CreeberDocument12 pages1 Digital Theory: Theorizing New Media: Glen CreeberMaria Camila OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Media Culture, Mass Culture and Popular Culture, Critical ReflectionDocument4 pagesMedia Culture, Mass Culture and Popular Culture, Critical Reflectionmaria joão sousaNo ratings yet

- Social Injustice Revision - EditedDocument5 pagesSocial Injustice Revision - EditedCalvi JamesNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 Popular Culture & ICDocument8 pagesChapter 10 Popular Culture & ICAdelinaHocaNo ratings yet

- CDA Analysis - The MediaDocument24 pagesCDA Analysis - The Mediafede37No ratings yet

- Course Lecture 1Document39 pagesCourse Lecture 1Melisa DragotaNo ratings yet

- Critical Studies TheoryDocument20 pagesCritical Studies TheoryTiaraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Defining Pop CultureDocument5 pagesChapter 1 - Defining Pop CultureGreen GeekNo ratings yet

- Theories On Culture Unit I MGCDocument8 pagesTheories On Culture Unit I MGCsnehal khadkaNo ratings yet

- Book ReviewDocument5 pagesBook ReviewHoney MoonNo ratings yet

- A Cultural Studies Approach To Gender, Race, and Class in MediaDocument7 pagesA Cultural Studies Approach To Gender, Race, and Class in MediaLinda LangitshabrinaNo ratings yet

- 205 GRCM PP 1-33Document32 pages205 GRCM PP 1-33loveyourself200315No ratings yet

- Media Studies Theory (Classic)Document3 pagesMedia Studies Theory (Classic)Steph HouseNo ratings yet

- Cinema and Cultural Studies PDFDocument6 pagesCinema and Cultural Studies PDFCristina CherryNo ratings yet

- "Voices Offstage:": How Vision Has Become A Symbol To Resist in An Audiology Lab in The U - SDocument18 pages"Voices Offstage:": How Vision Has Become A Symbol To Resist in An Audiology Lab in The U - SHarshit AmbeshNo ratings yet

- Transcendental Influence of K-PopDocument9 pagesTranscendental Influence of K-PopAizel BalilingNo ratings yet

- EDM Pop A Soft Shell Formation in A NewDocument21 pagesEDM Pop A Soft Shell Formation in A NewZulfiana SetyaningsihNo ratings yet

- Cultural Studies 1Document29 pagesCultural Studies 1moebius70No ratings yet

- What Is Popular Culture? A Discovery Through Contemporary ArtDocument41 pagesWhat Is Popular Culture? A Discovery Through Contemporary ArtleiNo ratings yet

- Paper 1Document13 pagesPaper 1Brennan VaughnNo ratings yet

- Duwende Ee-1aDocument4 pagesDuwende Ee-1aBright Light ServicesNo ratings yet

- JEP 1 2008 05 WANG Reconceptualizing The Role of Culture in Media Globalization Reality Television in Greater ChinaDocument19 pagesJEP 1 2008 05 WANG Reconceptualizing The Role of Culture in Media Globalization Reality Television in Greater ChinaAbidahyeNo ratings yet

- Popular CultureDocument6 pagesPopular CulturemishrinNo ratings yet

- Krishna Article 1Document16 pagesKrishna Article 1Ellie SmithNo ratings yet

- Unit II: A World of Ideas: Cultures of Globalization: Lesson OpeningDocument6 pagesUnit II: A World of Ideas: Cultures of Globalization: Lesson OpeningNikhaella Sabado100% (1)

- Research Paper GuoDocument22 pagesResearch Paper Guoapi-609103971No ratings yet

- 2 - 2 Prasad 2018Document25 pages2 - 2 Prasad 2018Kushal TekwaniNo ratings yet

- StauarthallDocument12 pagesStauarthallhari kiranNo ratings yet

- Audience IdeasDocument2 pagesAudience IdeasRFrearsonNo ratings yet

- Uses Gratifications Why Do People Watch TVDocument8 pagesUses Gratifications Why Do People Watch TVRFrearsonNo ratings yet

- Songs of Innocence and ExperienceDocument52 pagesSongs of Innocence and ExperienceRFrearsonNo ratings yet

- Narrative Patterns in GenreDocument1 pageNarrative Patterns in GenreRFrearsonNo ratings yet

- Manipulating TimeDocument2 pagesManipulating TimeVishal RajNo ratings yet

- Sound Sound Sound Sound Sound Sound Sound: Diegetic and Non-Diegetic SoundDocument3 pagesSound Sound Sound Sound Sound Sound Sound: Diegetic and Non-Diegetic SoundRFrearsonNo ratings yet

- How To Read A Film StillDocument1 pageHow To Read A Film StillRFrearsonNo ratings yet

- Camera Angles2Document1 pageCamera Angles2RFrearsonNo ratings yet

- DistributionDocument1 pageDistributionRFrearsonNo ratings yet

- Hot Fuzz NotesDocument1 pageHot Fuzz NotesRFrearsonNo ratings yet

- Film Distribution WorksheetDocument1 pageFilm Distribution WorksheetRFrearsonNo ratings yet

- Yr 12 Schedule 201112Document2 pagesYr 12 Schedule 201112RFrearsonNo ratings yet

- Avatar Mind MapDocument1 pageAvatar Mind MapRFrearsonNo ratings yet

- Section BDocument2 pagesSection BRFrearsonNo ratings yet

- Budget CostsDocument1 pageBudget CostsRFrearsonNo ratings yet

- Selected Key Terms For Institutions and AudiencesDocument7 pagesSelected Key Terms For Institutions and AudiencesRFrearsonNo ratings yet

- This Is England MindmapDocument1 pageThis Is England MindmapRFrearsonNo ratings yet

- Key Quotes What It's About: Thematic LinksDocument1 pageKey Quotes What It's About: Thematic LinksRFrearsonNo ratings yet