Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Berezkin Pleiades As Path of Birds and Girl in The Moon

Uploaded by

szaman10Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Berezkin Pleiades As Path of Birds and Girl in The Moon

Uploaded by

szaman10Copyright:

Available Formats

ARCHAEOLOGY, ETHNOLOGY & ANTHROPOLOGY OF EURASIA

Archaeology Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 37/4 (2009) 100113 E-mail: Eurasia@archaeology.nsc.ru

100

ETHNOLOGY

Yu.E. Berezkin

Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, Russian Academy of Sciences, Universitetskaya Nab. 3, St. Petersburg, 199034, Russia. E-mail: berezkin1@gmail.com

THE PLEIADES AS OPENINGS, THE MILKY WAY AS THE PATH OF BIRDS, AND THE GIRL IN THE MOON: NORTHERN EURASIAN ETHNO-CULTURAL LINKS IN THE MIRROR OF COSMONYMY*

The Baltic-Finnish and the Baltic cosmonyms mostly coincide, while the Baltic and Slavic ones are different. Baltic-Finnish variants nd parallels in texts of the peoples of the Middle Volga. The interpretation of the spots in the Moon as a girl or young woman with water-pails is widespread across all of Northern Eurasia, being also typical of the North American Northwest Coast, the Algonquians to the north of the Great Lakes, and of the Maori. Part of Siberian, North American and Maori texts include a motif of a bush clutched by the person. The interpretation of the Pleiades as a sieve can be a variation of an Eurasian image of stars as openings in the sky. The Milky Way as the path of birds is typical of the Balts, Finno-Ugrians, and some Turkic peoples, as well as of the Amur Evenki and the Algonquians. These cosmonyms spread from the East to the West. They are almost completely unknown among the Samoyeds. Keywords: Cosmonymy, the Pleiades, the Milky Way, lunar spots, Samoyeds, Turks, Siberian peoples, Indians of the North American Northwest Coast, Algonquians, Salish.

Seven objects of the night sky attracted most of the attention of Eurasian cultures outside of the Tropical zone. These are the Moon with its dark spots on its disc, Venus, the Milky Way, the Big Dipper, the Pleiades, the Belt of Orion, and Polaris. Other planets, stars, and constellations were singled out by some cultures but ignored by others. Though the number of Eurasian cosmonyms is great, most of them are either rare or mere variants of a few dominant forms of interpretation. The conservatism of cosmological vocabulary and of corresponding mythopoetic ideas makes them a source of data on ethno-cultural development in the remote past.

*This work was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (Project 07-06-00441-a), INTAS (Project 0510000008-7922), and the programs of the Presidium of the Russian Academy of Sciences: Adaptation of Peoples and Cultures to Environmental Changes, Social and Technogenic Transformations and Historical and Cultural Heritage and Spiritual Values of Russia.

The areal distribution of several cosmonyms recorded recently or preserved in the written sources do not coincide with the borders of linguistic families. In particular, cosmonymic vocabularies of the Balts and the Baltic Finns are identical even though the languages of these peoples belong to two unrelated families. Everywhere in the Eastern Baltic, the Milky Way is the path of (migratory) birds, the Pleiades are a sieve, a girl with pails in her hands is seen in the Moon. However, everywhere to the south and west of the Baltic Sea (excluding those areas of Poland and Belarus where Baltic languages were relatively recently replaced by Slavic languages (G adyszowa, 1960: 19, 28, 30; Niebrzegowska, 1999: 149; Vaik nas, 2004: 169170), the Eastern Baltic-type cosmonymy is absent. Exceptions are few. The path of birds is known to the Luzhitsa Sorbians (Azimov, Tolstoi, 1995: 118); the interpretation of the Pleiades as a sieve was recorded among the Hungarians (Mndoki, 1963: 519520; Zsigmond, 2003: 434) and northern Italians (Volpati, 1933a: 206); the girl in the Moon is typical

Copyright 2010, Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.aeae.2010.02.012

Yu.E. Berezkin / Archaeology Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 37/4 (2009) 100113

101

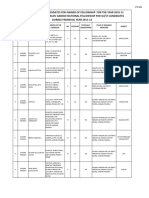

of most of Bulgaria and Macedonia, with an isolated case in Romania (Cenev, 2004: 47; Marinov, 2003: 28; Mladenova, 2006: 137, 263264, map 29). Despite these exceptions, there is no doubt that a basic cosmonymic border divides the Balts and the Slavs, but is absent between the Balts and the Baltic Finns. What historical processes could have produced such a boundary? The Pleiades as openings in the sky Putting aside the association of the Pleiades with a group of people (images of this sort are recorded in various areas but are very different from each other), three basic variants of interpretation of this star cluster are widespread in Europe (Fig. 1). The cosmonyms a hen with its chickens, brood, chickens, pullets and the like are typical of Western, Southern and Central Europe, the Balkans, and Western Ukraine (Andree, 1878: 106; Boneva, 1994: 12; Chubinsky, 1872: 14; Jankovich, 1951: 141; Krappe, 1938: 152; Lszl, 1975: 604; Mati etov, 1972: 49; Mladenova, 2006: 8993; Niebrzegowska, 1999: 145; Smith, 1925: 124; Svjatskii, 1961: 120; Volpati, 1932: 194205; 1933a: 507). Inside this zone, they are absent only across most of the territory of the former Yugoslavia and among the peoples of the Pyrenees

(other than the Basques). Outside of Europe, a hen with its chickens is typical of West Africa and Sudan (Hirschberg, 1930: 326327; Meek, 1931: 200; Schwab, 1947: 413; Spieth, 1906: 557; Volpati, 1933a: 507), Northeast India, and of Southeast Asia (Andree, 1878; Smith, 1925: 114; Vathanaprida, 1994: 3941). It is possible that in the past the same cosmonym was known in the Near East and North Africa (Volpati, 1933a: 195), though now the Arabic Suraia (chandelier) is the only word that is used for the Pleiades. The Touaregs call the Pleiades chickens (Rodd, 1926: 226). Because this cosmonym is absent in ancient sources and because it is related to the domestic hen, one can suggest its relatively late spread in Europe. Cosmonyms that mean a nest (or an egg, eggs) of wild duck, a ock of ducks are typical of the Nenets (Khomich, 1974: 232), Komi-Zyryans (Svjiatskii, 1961: 120), Udmurts (Wichmann, 1987: 214, 273), as well as of the Ob Ugrians (Munkcsi, 1908: 255; 1996; Steinitz, 19661993: 1412, 1636). In Siberia and in Northeast Europe, a correlation of this cosmonym with Uralic languages is noticeable, although there are a number of exceptions. Among the Selkups, the Pleiades are hares shelves or hares droppings (Tuchkova, 2004: 212). The meaning of this name has been lost, no parallels in other traditions are known. Among the Nganasans, the Pleiades are hunters who catch the souls of dead men and reindeer (Popov, 1984: 48). The Enets name Kondiku (Dolgikh, 1961: 24) either has no Samoyed etymology

1 2 3

Fig. 1. Major variants of folk-names for the Pleiades in Europe.

1 hen and chickens; 2 brood or nest of (wild) duck; 3 sieve.

102

Yu.E. Berezkin / Archaeology Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 37/4 (2009) 100113

or was so distorted during the recording that it became unrecognizable*. Among the Khakas who speak a Turkic language, the Pleiades are also a ducks nest or a ock of ducks (Butanaev, 1975: 238). The ducks nest among northern Russians (Potanin, 1883: 730; Rut, 1976: 15) is a clear legacy of the pre-Slavic substratum. Moving to the east of the Urals, the Russians brought the ducks nest to Siberia. Citing U. Harva, some authors claimed the existence of such an image among the Yakuts and the Kamchadals (Lundmark, 1982: 105; Mladenova, 2006: 196), but these statements result from a misunderstanding: Harva mistook the Russian cosmonym ducks nest for a translation of the name of the Pleiades from native languages (Harva, 1933: 135). M. Rut seems to have made a similar mistake discussing Enets materials (1987: 47). A continuous and compact area of the ducks nest that is basically located inside the territory of the former spread of Uralic languages but crosses the language borders of both the Samoyeds and the Finno-Ugrians allows us to suggest a connection of this cosmonym with some extinct people. If this people spoke a language of the Uralic family, no direct language descendents remained from them. The designation of the Pleiades as a sieve is characteristic, as was mentioned, for the Eastern Baltic where it was recorded among ancient Prussians, Lithuanians, Letts, Livonians, Estonians, Finns (Allen, 1899: 397; Andree, 1878: 107; Kerbelite, 2001: 65; Kuperjanov, 2003: 183185; Mndoki, 1963: 519; Nepokupnyi, 2004; Vaik nas, 1999: 167; 2004: 169). There is no data on the Votians and Vepses (Votian ideas probably did not differ much from Estonian ones), while for the Saami the Pleiades are girls (Charnolusky, 1930: 48; Lundmark, 1982: 105). In the Middle Volga region, sieve as a name for the Pleiades has been recorded among the Chuvash (Mndoki, 1963: 520; Sirotkin, Ivanov, 1970: 128; Yuhma, 1980: 266; Zolotnitsky, 1874: 22), Mari (Aktsorin, 1991, No. 37: 83), Tatars (Potanin, 1883: 729; Vorobyev, Hisamutdinov, 1967: 316), Bashkirs (Maksyutova, 1973: 383), and Udmurts, probably the southern groups only (Nikonov, 1973: 376; Wichmann, 1987: 107). In the Volga region, only the Mordvinians name the Pleiades a beehive (Svyatsky, 1961: 121). Such an interpretation or variants which are similar to it (an apiary, a nest of wasps) is also known to the Russians, Ukrainians, Bulgarians, and Hungarians (Mladenova, 2006: 115). Among the Russians, a sieve as a name for the Pleiades has been recorded in Vologda Province and among Russian migrants in areas beyond the western border of the Russian ethnic territory (Rut, 1987: 15; Svyatsky, 1961: 121). The sieve is typical not only of the Eastern Baltic and Middle Volga areas but also for Dagestan where it is recorded among the Kumyks, Laks, Avars, Andi, Dargins, and Tavli (Gamzatov, Dalgat, 1991: 304305; Potanin,

*Personal communication of I.P. Sorokina (2008).

1883: 729730). G. Potanin found a sieve as a name for the Pleiades among the Kazakhs of the Middle Zhuz and among Astrakhan Tatars (1881: 126; 1919: 84). A suggested Persian parallel (Nepokupnyi, 2004: 80) is not correct: the words Parvin (the Pleiades, from the rst) and parvizan (sieve) are not from the same root*. Among the Chukchi and Koryak of the Asian northeast, W. Bogoras and W. Jochelson recorded cosmonyms Ketmet and Ktmc (Bogoras, 1939: 29; Jochelson, 1908: 122) and translated them as a small sieve, though at least among the Chukchi the basic image of the Pleiades was a group of women (Bogoras, 1939: 24). A word similar to Ketmet really means sieve (for washing salmon roe) though not in the Paleoasiatic but in the Yukaghir language**. There are two basic, compact, and large areas for the Pleiades as a sieve, the Eastern Baltic and the Middle Volga. Historically, they have in common a Baltic substratum or Baltic in uence (Napolskikh, 1997: 158 161), and the Battle-Axe and Corded Ware cultures spread there in the earlier period (I do not here address the question as to whether there was a continuity between the bearers of these archaeological cultures and the proto-Balts). Later in the Volga region, this cosmonym was transmitted from the Finno-Ugrians to the Turkic peoples. The sieve could have reached Dagestan and Kazakhstan from the Volga region in times of the Golden Horde (Napolskikhs suggestion) though so late a diffusion does not fit well with a specific parallel between the Lithuanians and the Laks: the sky sieve was used by God to winnow cereal grains (Halidova, 1984: 160; Nepokupnyi, 2004: 77). Unfortunately, the Lithuanian mytheme is known only from A. Mitskevics poem Pan Tadeusz, which is not suf cient for drawing reliable conclusions. The position of Hungarian materials is also unclear. Though the Hungarian word szita for the Pleiades is borrowed from Slavic (Mndoki, 1963: 519520), the constellation in the sky is really viewed as something that has openings (Zsigmond, 2003: 434). The fact that the Hungarians are the only people in the Balkans who have this concept makes it doubtful that such an interpretation of the Pleiades was borrowed from the Slavic population of Pannonia. And if the Hungarians brought it from the East, what was the source? In Western Europe, the cosmonym sieve (crivello) is recorded only in the Alto Adige district of Northern Italy (Volpati, 1933a: 206; 1933b: 21). It deserves to be mentioned that crivello is both a sieve and shovel for winnowing grain. To sum up, the origins of sieve as a designation of the Pleiades in Europe is far from obvious. It is not clear whether all versions had a single source. But if we look at the names of the star objects in the pan-Eurasian perspective, the given cosmonym can be interpreted as a particular case of a more

*Personal communication of I.M. Steblin-Kamensky (2008). **Personal communication of O.A. Mudrak (2008).

Yu.E. Berezkin / Archaeology Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 37/4 (2009) 100113

103

general and more widely known image, i.e. the conception of stars as openings. 1 Siberian parallels are important, which include not only 2 the Paleoasiatic data mentioned above. The etymology of the name of the Pleiades in Turkic languages (Ulker, Yurker, Yurkar, etc.) is disputable. According to one of the hypotheses, it is a vent, to pierce (Nikonov, 1980b: 296). A. Dybo, the leading specialist in Altaian languages, does not consider this suggestion to be substantiated*. At the same time, it is supported for the Yakuts by a folklore text: the hero makes mittens of wolf skin to stop up holes in the sky from which an icy wind blows and these holes are the Pleiades (Holmberg, 1927: Fig. 2. Areal distribution of the interpretation of stars as openings in the rmament. 418). Among the Orochi and the 1 continuous distribution is probable; 2 particular areas where data has been received. Uilta (the Oroki) of Sakhalin, the Pleiades in some cases also 1976: 79; Dulzon, 1966: 1517; 1972: 8386), Yakuts are seven openings (Podmaskin, 2006: 432) though the (Ergis, 1967: 134; Gurvich, 1977: 199), Evenki (Vasilevich, seven women are more usual for the Lower Amur region. 1959: 161162; Voskoboinikov, 1960: 296), Lamut No special narratives exist related to this name but the (Burykin, 2001: 114), and Negidals*. Indirect or vague same word is used to denote the branchial openings of the information of a similar nature exists for the Chukchi and lamprey**. Beyond Northern Eurasia, the conception of Kamchadal (Ergis, 1974: 134; Jochelson, 1961: 7174). In the Pleiades as stars surrounding an opening can be found North America, the concept of stars as openings is typical among the Ojibwa (Speck, 1915: 48). Given that there are of the Arctic where it is registered among the Central Yupiq, other Asiatic North American parallels in mythology including Nunivak Island, Inupiat, the Mackenzie Delta, (Berezkin, 2006), a historic connection between this image Caribou, Netsilik and Iglulik Eskimo (Lantis, 1946: 197; and the Siberian ideas is not excluded. MacDonald, 1998: 33; Nelson, 1899: 495; Ostermann, If we consider not just the Pleiades but any stars 1942: 56, 58; 1952: 128; Rasmussen, 1930: 79). This regarded as openings in the sky, such a motif is known in fact should be considered in relation to a hypothesis of a Africa, particularly in Liberia, the mouth of the Congo and relatively recent Siberian origin of the Eskimo, different South Africa (Koekemoer, 2007: 75; Pechul-Loesche, from the origins of other American natives. The image of 1907: 135; Schwab, 1947: 413), in western Indonesia, a particular star (usually Polaris) as an opening through particularly among the Mentawei, Klemantan and Kayan which one can penetrate into the Upper World is known (Hose, MacDougall, 1912: 142, 214; Schefold, 1988: to many American Indians, but the general concept of 71), and in Southern China among the Miao (Its, 1960: stars as holes in the rmament is only rarely recorded in 107). Nevertheless, the conception of stars as openings is North and South America among groups isolated from predominant only in Northern Eurasia, in the American each other such as the Thompson River Salish, Totonac, Arctic, and possibly in Borneo (Fig. 2). As isolated cases Tucuna, and Tupari (Boas, 1895, No. 4: 1718; Caspar, it is recorded among the Estonians (Kuperjanov, 2003: 1975: 188; Ichon, 1969: 36; Nimuendaju, 1952: 123124). 125), Mari (Aktsorin, 1991, No. 26: 5960), Komi (Ariste, An absolute majority of American natives as well as the 2005, No. 136: 163), and seems to be a norm among the peoples of Africa, Australia, Oceania, and the Indo-Paci c Nenets (Nenyang, 1997: 214, 224; Helimski, 1982: 399), borderlands of Asia interpreted stars taken as a particular Nganasans (Popov, 1984: 45; Simchenko, 1996: 191), class of objects in only one way, i.e. as persons, spirits, or Khanty (Lukina, 1990, No. 8: 6769), Kets (Alekseyenko, living creatures of some kind.

*Personal communication of A.V. Dybo (2008). **Personal communication of A.M. Pevnov (2008). *Personal communication of A.M. Pevnov (2008).

104

Yu.E. Berezkin / Archaeology Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 37/4 (2009) 100113

1883: 740; Vereschagin, 1995: 81), Komi (Erddi, 1968: 110; Napolskikh, 1992: 6; Potanin, 1883: 943), Kazakhs The second cosmonym whose western limit coincides (Karutc, 1911: 35; Potanin, 1881: 126127; Sidelnikov, approximately with the border between the Lithuanians 1962: 268), Kirgiz (Abramzon, 1946: 65; Fielstrup, 2002: and Poles is the designation of the Milky Way as the path 217, 227; Potanin, 1881: 127), and Karakalpak (Nikonov, of birds (Fig. 3) or, more precisely, of migratory birds like 1980a: 248). The Turkmen preserved a cosmonym of geese, ducks, swans or cranes. Researchers sometimes see in a path of birds up to the middle of the 19th century the path of birds a variant of a more general interpretation (Nikonov, 1980a: 248; 1980b: 293). It was known also to of the Milky Way as the route of dead souls (Kuperjanov, the Khanty and Mansi (Erddi, 1968: 109110; Munkcsi, 2001). The two ideas are quite similar in meaning (Azimov, 1908: 254; Napolskikh, 1992: 8), and up to the 16th century Tolstoy, 1995: 118), but the cosmonym path of birds is to the Hungarians (Nikonov, 1980: 248) who seem to have still speci c enough and sometimes coexists with the route brought it from their eastern homeland. Another name for of dead souls as a distinct image (Aichenwald, Petrukhin, the Milky Way which is widespread among the Ob Ugrians Helimski, 1982: 164). The area of its spread covers only is ski trail, connected to the myth about the hunt of the part of the territory where seasonal migrations of birds is a sky elk (Erddi, 1968: 116). It is either the only or the particular theme in folklore traditions. most dominant name among Samoyeds and the peoples of The path of birds (path of cranes, birds path, Eastern Siberia, Lower Amur, and Alaska. Among the Ob trace of the route of birds, etc.) is known mainly to Ugrians, both names are found, but they are connected with peoples from three language families, i.e. the Balts, Finnodifferent cycles of mythological ideas. Ugrians (but not Samoyeds), and Turks. These include The Russians called the Milky Way, a path of geese the Letts and Lithuanians (G adyszowa, 1960: 7778; in Vologda, Vyatka, Perm, Tula, Smolensk, and Kaluga Kerbelite, 2001: 57; Vaik nas, 1999: 173), Livonians Provinces and in Siberia (Gura, 1997: 671; Rut, 1987: 13), (Toivonen, 1937: 123), Estonians (Kuperjanov, 2003: as did the Belorussians in Polesie near Pinsk (Gura, 1997: 150151; Pustylnik, 2002: 268), Finns (Erddi, 1968: 658), and the Ukrainians in Volyn near Lutsk (Chubinsky, 110111), Saami (Erddi, 1968: 111; Toivonen 1937: 123), 1872: 15; Moshkov, 1900: 205). Across approximately Mari (Aktsorin, 1991: 5556; Erddi, 1968: 110; Vasiliev, the same areas of Polesie and Volyn, the designation of 1907: 12), Mordvin (Devyatkina, 1998: 118), Chuvash the Pleiades as a sieve has been recorded. At the same (Ashmarin, 1984: 26; Rodionov, 1982: 168; Zolotnitsky, time, the areal correlation of sieve and path of birds is 1874: 22), Volga Tatars (Vorobyev, Hisamutdinov, 1967: not complete; the spread of the latter cosmonym is wider. 316), Bashkirs (Barag, 1987: 33; Rudenko, 1955: 315), Important is the addition not so much of the Saami but Udmurts (Erddi, 1968: 110; Moshkov, 1900: 197; Potanin, especially of the Turks beyond the Volga region, i.e. the Kazakhs, Kirgiz, Karakalpak, and Turkmen. However not all of the Turkic people share this concept. The absence of the path of birds across the Sayan-Altai region as well as among the Uzbeks (and most probably the Uigurs) makes it doubtful that this cosmonym had a proto-Turkic origin. In Southern Russia, across most of the Ukraine and among Southern Slavs, this cosmonym is absent. The path of birds is known to the Evenki of the Middle Amur area (Vasilevich, 1969: 210) and in America to the Algonquians who live to the north of the Great Lakes, in particular to the Ojibwa, including two groups near Huron Lake (Miller, 1997: 60; Speck, 1915: 79) and the Saulteax (Hallowell, 1934: 394). It is not clear if the materials of Fig. 3. Areal distribution of the interpretation of the Milky Way as the path the Tutchone Athabascans who of migratory birds.

The Milky Way as the path of birds

Yu.E. Berezkin / Archaeology Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 37/4 (2009) 100113

105

live in Canada near the border with southern Alaska are related to the same concept. Among the Southern Tutchone, the Milky Way marks the path of the loon the personage of a myth about a hunter who became blind and then received his sight again (McClelland, 1975: 78). Taking into consideration the areal distribution of the path of birds, there are no reasons to connect the origin of this cosmonym with the Balts or Turks. To the Finno-Ugrians the path of birds most probably was known from ancient times. However, the lack of this motif among the Samoyeds makes a proto-Uralic attribution dif cult. At the same time, if this motif did not emerge independently among the Evenki and Algonquians, it had to appear in Eurasia long before the split between the two major branches of Uralic languages. The water-carrier in the Moon

The third cosmonym whose western limits in Europe coincide approximately with the border between the Balts and the Slavs is the girl with pails in the Moon (Fig. 4). Two tales related to it are widely known. According to one, the Moon takes pity on an orphan girl, a poor stepdaughter, or the like, who was sent to fetch water and takes her up to him. According to the other, the Moon does this as a punishment for a girl or young woman who was arrogant and boastful. Since then the gure of a girl with pails can be seen in the Moon. Among Balts and Baltic Finns, in particular the Lithuanians (Kerbelite, 2001: 70; Laurinkene, 2002: 365; Vaik nas, 2006: 158), Letts (Pogodin, 1895: 440), Estonians 1 (Kuperjanov, 2003: 72; Peebo, Peegel, 1989: 282; Sullv et al., 2 1995: 94), and Votians (Ariste, 1974: 5; 1977: 175; Ernits, Ernits, 1978: 579) both variants are recorded together with other, more rare, explanations. For example, among the Karelians, the girl holds in her hands a milk-pail (Evseev, 1981: 313). No details of the Vepsian legends are provided by the source (Egorov, 2003: 129). Among the Saami, the Sun takes the girl to give her in marriage to his son and throws her into the Moon where she is now seen with her yoke and pails (Charnolusky, 1962: 6879). In the Volga-Permian region, the water-carrier in the Fig. 4. Areal distribution of the interpretation of spots on the Moon as of a person Moon is present among the who went to fetch water, holds a water pail in her or his hands. 1 girl or young woman; 2 two children, small boy, lad, or man. Komi-Zyrians (Ariste, 2005,

No. 109: 105; Limerov, 2005, No. 58: 5556), KomiPermiaks (Konakov et. al., 2003: 312), Udmurts (Potanin, 1883: 776; Vereschagin, 1995: 8586; Vladykin, 1994: 322), Chuvash (Ashmarin, 1984: 25; Denisov, 1959: 1516; Egorov, 1995: 120; Vardugin, 1996: 260), Mari (Aktsorin, 1991, No. 3742: 8387; Moshkov, 1900: 197), Bashkirs (Nadrshina, 1985, No. 6, 7: 12, 13; Rudenko, 1955: 315), and Volga Tatars (Vorobyev, Hisamutdinov, 1967: 314315). In this area, the version with an orphan girl is widely known, while the version with the woman who made fun of the Moon is absent. The Bashkirs and Tatars have a story of the Moon who carried away the girl because he fell in love with her. As with the sieve, the Mordvinians represent an exception; a search for the motif of the water-carrier in the Moon in their folklore was unsuccessful. Among the Russians, the motif of the water-carrier as a poor orphan-girl seems to be recorded only in Vyatka Province (Belova, 2004, No. 1305: 521), while the motif of a young boy and girl who went after water and were looking at the Moon too intently was recorded in Arkhangelsk Province (Gura, 2006: 462). This data concerning the northern Russians is hardly exhaustive because this part of regional cosmonymy has never been in the focus of research. The Ukrainian watercarrier in the Moon was recorded only once, in the Volyn region (Gura, 2006: 262), i.e. in the same area where the path of birds was also present. Just as the path of birds, the water-carrier in the Moon in its poor stepdaughter version is present among the Kirgiz (Brudny, Eshmambetov, 1968: 1113) and the

106

Yu.E. Berezkin / Archaeology Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 37/4 (2009) 100113

Kazakhs. The Kazakh materials were recently obtained in Ak Tba Province*. Previously, the Kazakh ideas about the spots in the Moon were not investigated, so the lack of data on eastern groups of Kazakhs as well on Karakalpak is not signi cant. From the Kirgiz the motif of a poor stepdaughter who was sent to fetch water and was taken up into the Moon may have spread to the Pamir region, where it is known at least to the Vakhan**. The water-carrier in the Moon (in its two variants, the poor stepdaughter and the woman of indecent behavior) is recorded among the Siberian Tatars (Valeev, 1976: 329; Urazaleev, 2007: 4). The motif is not known either among the Northern Samoyeds or among the Northern Selkup. Among the Southern Selkup, it is a small girl who went to fetch water, or a young girl who teased the Moon (Golovnev, 1995: 330331; Pelikh, 1972: 322323). Among the Khanty, it is a small girl (alone or together with a boy) who teased the Moon (Kulemzin, Lukina, 1978, No. 4, 5: 15, 16) and among the Mansi it is a girl with pails; explanations for this image seem to be lost***. Among the Kets, the Moon was teased by a young girl or woman (Alekseyenko, 1976: 84). Among the Khakas, the story about a poor stepdaughter was widespread; the same is among the Kirgiz, Kazakhs, and Siberian Tatars (Butanaev, 1975: 232). For the Altai region, the motif is not typical. In only one of many narratives that describe how the ogre Tilbegen (Jelbegen, etc.) got to the Moon, the Moon took him when he went to fetch water and had a yoke and pails in his hands (Anokhin, 1997: 56). Data on the Shor and Tuvans are absent, and among the Tofa, the person who ended up in the Moon is an orphan boy sent to fetch water (Rassadin, 1996, No. 3: 10). In a tale of the Darkhats who live in Mongolia near Lake Khubsugul, two boys went for water and ended up in the Moon****. Three texts with such a plot were recorded, one of them from an informant whose parents were Halha Mongolians but lived among the Darhats of Hubsugul Aimak. The motif is unknown in other areas of Mongolia, and it seems that it is connected only with Siberia, not with Central Asia. The Hubsugul Darhats relatively recently shifted to use of the Mongolian language, and their culture is similar to that of Todzha Tuvans

*Personal communication of I.V. Stasevich (2006). **Personal communication of B. Lashkarbekov (2006). ***Personal communication of O.S. Ivanova (2009). ****Arkhipova A.S, Dorj D., Kozmin A.V., Neklyudov S.Yu. (head), Sanjahand I., Solovyeva A.A. Materials of the Russian-Mongolian Folklore Expedition of the Center of Typology and Semiotics of Folklore of the Russian University for the Humanities and Institute of Language and Literature of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences in Hubsugul and Bulgan Aimaks, August 2007 (within the framework of the project Mongolian Mythological Traditions: Areal and ComparativeTypological Aspects; Project 07-01-92070e/G sponsored by the Russian Foundation for the Humanities and the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science of the Mongolian Peoples Republic.).

(Zhukovskaya, 1980: 151). In the early 20th century, the Darhat shamans still used the Tuvan language to address spirits (Sanzheev, 1930: 7). Different groups of Buryats also seem to inherit the water-carrier in the Moon from a pre-Mongolian substratum. Among them this tale was recorded many times in a form which was near to the poor stepdaughter: a girls stepmother or her own mother who married another man sends her to fetch water and expresses a wish that the Moon would take her (Galdanova, 1987: 17; Hangalov, 1958: 319; 1960: 14; Potanin, 1883: 190193; Sharakshinova, 1980: 4950). Among several groups of Yakuts (Alekseyev, Emelyanov, Petrov 1995: 197199; Gurvich, 1948: 130; 1977: 199; Hudyakov, 1969: 279, 372373; Ovchinnikov 1897, No. 5, 6: 179181; Popov, 1949: 260261; Seroshevsky, 1896: 667; Tolokonsky, 1914: 89), Evenki (Potanin, 1893: 385; Rychkov, 1922: 83 84; Vasilevich, 1936: 7374; 1959: 165; Voskoboinikov, 1967: 159), and Lamut (Novikova, 1987: 4344), the water-carrier in the Moon is known mainly in its poor stepdaughter variant though in rare cases the motif of two children who looked at the Moon and were drawn to it is also recorded (Hudyakov, 1969: 279). The watercarrier in the Moon, in a variant identical to the poor stepdaughter of the Evenki, is present among the Negidal (Hasanova, Pevnov, 2003: 5556; Lopatin 1922: 330) and Nanai (Arsenev, 1995: 152; Chadaeva, 1990: 34, 35; Lopatin, 1922: 330), but not among peoples of Primorye and Sakhalin. This is an argument in favor of a connection of this motif in this region with the Tungus and not with a pre-Tungus substratum. To the Udige and the Nivh the very image of a girl or a woman seen in the Moon and holding a pail or a scoop was, however, known (Ishida, 1998: 24; Kreinovich, 1973: 32, 33; Podmaskin, 1991, No. 17: 125). The Ainu of Sakhalin and Hokkaido see in the Moon a girl who went to fetch water and was taken by the Moon to become his wife (Pilsudski, 1912, No. 3: 73-74; 1991, No. 3: 7072) or who was envious and insulted the Moon, accusing her of being idle (Ishida, 1998: 2425), or else the Ainu see in the lunar disc a boy who insulted the Moon in the same way (Batchelor, 1927: 260). The motif of a woman seen in the Moon with pails in her hands (no other details) is known in southern Japan*, while myths recorded on the Ryukyu Islands (Miyako and Okinawa) explain how a man with a water-pail ended up in the Moon (Nevsky, 1996: 267269). In Northeast Asia, the poor orphan variant of the water-carrier in the Moon is recorded among the Yukaghirs (Nikolaeva, Zhukova, Demina, 1989, No. 2: 21 23) and among Russian-speaking dwellers of the village of Markovo who have Yukaghirs (the Chuvan) among their ancestors**. The water-carrier is absent among

*Personal communication of K. Inoui (2005). **Hakkarainen M.V. Interview with Yury Dyachkov. Markovo. 02.06.1999.

Yu.E. Berezkin / Archaeology Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 37/4 (2009) 100113

107

Paleoasiatic peoples, though the Chukchi (Bogoras, 1928, No. 2: 301302; 1939: 2223), Koryak (Beretti, 1929: 36), and Kamchadal (Porotov, Kosygin, 1969: 33) have a less speci c motif of a girl who ended up in the Moon. A special detail is typical of many Siberian texts (the Khakas, Tofa, Buryat, Ket, Selkup, Khanty, Yakut, southeastern Evenki). When the water-carrier was taken up to the Moon, he or she tried to hold a bush and now is seen on the lunar disc holding both the pails and the bush. The same detail is present among the Vakhan of Pamir and the Koryak. In the Koryak story (Beretti, 1929: 36), there is no mention of pails, but the entire episode with a girl whom her evil stepmother drove to a river to fetch water is similar to the Yakut and Evenki variants. In Southern Siberia, among the Teleuts, Altaians, and Khakas, this motif is not linked to the water-carrier motif, and it was an ogre who attempted to hold a bush to prevent being pulled up to the Moon. We can summarize that the motif of a girl or young woman who went to fetch water and ended up in the Moon is widespread across Eurasia from the Eastern Baltic to the Sea of Okhotsk. In the variants registered beyond this area but territorially adjacent to it, either the motif of water to be fetched by a person is lost, or else the actors are a boy, a man, or two children instead of a girl. Nowhere in this periphery, with the exception of the Koryaks, does the Moon take the water-carrier up to the sky because he feels sorry for her. In addition to the Mongolian, Japanese, and Paleoasiatic materials, the Scandinavian and Western European variants should be mentioned among these peripheral traditions. Thus in Ireland, people saw in the Moon two boys who carried a stick with a pail of water on it (Krappe, 1938: 120), while in Northern Germany it was a man with a pitcher in his hands, a child with a pail, a thief who carried two stolen pails with water, or two men who hold yokes with water-tubs (Ishida, 1998: 2021; Krappe, 1940: 168; Wolf, 1929: 5556). Also in Scandinavia (The Younger Edda), it was two children with a yoke and a pail (Mladshaya Edda, 1970: 20) or two old men who tried to drown the Moon with water (Krappe, 1938: 120). In the New World, the water-carrier in the Moon is present in the folklore of most of the Indians of the North American Northwest Coast and of the Frazer River valley of the neighboring Plateau area. Some texts are similar to the woman insults the Moon version that is typical of Eurasia. Tlingit. One of two girls says that the Moon is like her grandmothers labret. Immediately both girls are in the Moon. The one who insulted the Moon falls to the earth and is shattered, while her friend is now seen on the lunar disc with a pail in her hand (Swanton, 1908b: 453). Haida. A woman goes to fetch water and points at the Moon. It seems to her that somebody is sitting in the well and she points at this gure. At night she gets thirsty, returns to the well, somebody grasps her hand and pulls her up. She tries to hold onto a bush of berries and now is

visible in the Moon carrying the bush and a pail (Swanton, 1908a: 450452). Tsimshian (Ness River). A woman points at the Moon and at its re ection in the water. The Moon takes her to the sky while she is carrying a berry-bush. Now she is seen in the Moon with the bush and the water-pail in her hands (Boas, 1916: 864). Bella Coola. A woman with a pail of water in her hands is seen in the Moon (McIlwraith, 1948: 225). Oowekeeno. A little boy is crying, his sister puts him outdoors, and gives him a toy pail to play with. He keeps crying; she warns him that the Moon will take him away. The Moon descends and takes him; now he is seen in the Moon with a little pail in his hand (Boas, 1895: 217; 2002: 457). Kwakiutl. The Moon descends to earth, and asks for some water. A girl goes out with a pail, and he abducts her. When he descends again to abduct another girl, the mother of the rst one warns her of the danger. Nevertheless she comes out with a pail of water and is now seen in the Moon holding the pail in her hands (Boas, 1895: 191; 2002: 409). Shuswap. In the wintertime the Moon travels constantly. His wife asks where they are going to camp. The Moon suggests that she camps on his face. She jumps on it and is still seen there with her buckets and shovel, with which they melt snow (Teit, 1909: 653). Thompson. The Moon sends his sister to fetch water. Coming back she nds no place to sit and he suggests that she sit on his face. Now a woman with pails in her hands is seen in the Moon (Teit, 1898: 9192). Quinault. The Moon was as bright as the Sun. Many girls desired him but he chose a Frog. Now she is seen on the lunar disc holding a box with her property and a pail in her hands (Thompson, Egesdal, 2008: 207209). In the latter three texts, the motif of water-carrier typical of the Northwest Coast is combined with the motif, typical of the Salish, of a person, usually a Frog-woman, clinging to the face of the Moon and seen now as spots on the lunar disc. Beyond the Northwest Coast, the water-carrier is recorded among the Algonquians to the north of the Great Lakes. In a myth of Sandy Lake Cree, a woman, sending her son to fetch water, warns him not to look at the Moon. The lad disappears and is now seen in the Moon holding a ladle and a pail (Ray, Stevens, 1971: 81). In an Ojibwa myth, a woman cooks maple syrup and pours it from one pail into another. The Moon sees that the woman urinates on the same place. The Moon is offended and takes her to the sky. When the Sun, who was the Moons husband, learned of this, he punished his wife, making her carry the woman eternally. Now the woman with a pail is seen in the Moon (Jones, 1919: 637). The water-carrier in the Moon is known to the Maori of New Zealand. As soon as Hina scooped water with her gourd vessel, clouds hid the Moon, Hina stumbled

108

Yu.E. Berezkin / Archaeology Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 37/4 (2009) 100113

and the water poured out. Hina scolded the Moon, the Moon seized her and Hina clutched at a bush. Now she is seen in the Moon with a bush and a gourd vessel in hand (Ishida, 1998: 26). In another variant, it was a man, Rona by name, who ended up in the Moon (Reed, 1999, No. 16: 190192). In yet another version, Rona is the name of a woman (Dixon, 1916: 8788). It seems that the variant was predominant which had a female person end up in the Moon. Some incomplete parallels for this myth are found on other Polynesian islands, and water containers are seen in the Moon together with a woman (Beckwith, 1970: 220221; Dixon, 1916: 88; Williamson, 1933: 100). Though New Zealand is extremely remote from Siberia, the ultimate sources of the Maori myth should be looked for at a probable Austronesian homeland in East Asia because nothing of the kind is present in Melanesia and Indonesia. The motif of a bush grasped by a woman who came to the river and was pulled up to the Moon rmly links the Maori variant to those found among the Haida and Tsimshian and among many Siberian peoples. To attribute the spread of tales with such speci c details to the in uence of the Europeans or to think that they emerged independently would be unrealistic. Conclusions Distributions of the three cosmonyms described above largely coincide. Here are major tendencies. All three motifs are typical of the Eastern Baltic and Middle Volga regions. In two cases out of three (the Pleiades as a sieve and the water-carrier in the Moon) the southernmost of the Middle Volga groups, i.e. the Mordvin, is the only one in this region for which no data on these images are found. All these motifs are typical of some or of many of the northern Russian provinces and not typical of southern Russia or of the Ukraine except for a small enclave at Volyn. It is clear that these motifs came to the Eastern Slavs from a substratum population. Northern Samoyeds (Nenets, Enets, and Nganasans) are not familiar with these three motifs, while the Selkups, more precisely only the southern Selkups, have just one of them, the watercarrier in the Moon. The path of birds is known to all Finno-Ugrians and the water-carrier in the Moon is known to most of them other than the Mordvin and the Hungarians. The path of birds and the water-carrier in the Moon are present among the Kazakhs and the Kirgiz, while the Altai-Sayan Turks lack them. Among the Kazakhs of the Middle Zhuz, a sieve is recorded as a name for the Pleiades. To the east of the Yenisei River, only the motif of the water-carrier in the Moon is widespread, and among the Yakuts, Evenki, and Buryats it was recorded many times. However, considering a sieve as a particular variant, applied to the Pleiades, of the motif of stars as openings in the rmament, the sieve still

connects Eastern Europe with Siberia. In addition, the path of birds was also known to the Amur Evenki. The Algonquians to the north of the Great Lakes have the path of birds and the water-carrier in the Moon, and also a possible parallel for the image of the Pleiades as an opening in the sky. The water-carrier in the Moon is also typical of different Indians of the Northwest Coast and of the Salish in the southern Northwest Coast and northern Plateau areas. Taking into consideration the complete absence of such motifs among American Indians who lived further to the south than the Salish and the Ojibwa, a Siberian source of these images is plausible. If so, we have to push the dating of their spread in Eurasia back to the Early Holocene at the latest. When the ice caps melted, people of the northern territories of Eastern Europe came mainly from the south. Archaeologists trace the rst post-glacial cultures of the Eastern Baltic back to the Final Paleolithic Swiderian culture and this conclusion corresponds well to data from craneology and population genetics (Niskanen, 2002: 144 147). The spread of some mythological motifs also ts such a scenario (Napolskikh, 1990). However, the areal patterns of the motifs reviewed above make us suggest that some migration from the East also took place. Even if the Evenki and Algonquian data concerning the path of birds are ignored and the motif of stars as sky-openings is not considered speci c enough, the pattern of the spread of the water-carrier in the Moon makes the hypothesis of trans-Eurasian migration plausible. Remembering the detailed American and Polynesian parallels for the Eastern and Southern Siberian variants, the Northern Eurasian East, rather than the West should be suggested as the earliest zone of the spread of this motif. The Bulgarian-Macedonian enclave of the water-carrier clearly cannot be a source for Siberian, not to speak of Amerindian or Polyneisan myths, and Bulgarian materials rather demonstrate the existence of some late Baltic-Balkan links*. During the Final Pleistocene Early Holocene, more detailed ideas about the objects of the night sky probably had been forming in Northern and Central Eurasia. From Eurasia the corresponding ideas were brought to North America. In the Indo-Pacific borderlands of Asia, in Australia, South and Central America, the cosmonymy developed independently and does not demonstrate parallels with the North Eurasian North American

*To determine the origins of the water-carrier in the Moon in the Balkans it would be desirable to compare the BulgarianMacedonian materials with Serbian ones. Unfortunately, Serbian interpretations of the spots in the Moon are of late origin and include only variants typical of most of Christian Europe (Jankovich, 1951: 108109). A version which is speci c to Bulgarian variants (a boy and a girl come to a well and end up in the Moon) is found elsewhere only among northern Russians (Gura, 2006: 462).

Yu.E. Berezkin / Archaeology Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 37/4 (2009) 100113

109

set of images and plots, while in sub-Saharan Africa its development was minimal. Because new images in Siberia and Eastern Europe did not displace earlier ones but were added to them, small groups of migrants from the East probably were enough for spreading the new cosmonymy across most of Eurasia. If such migrants were forest hunters and shermen, the natural limit of their western spread had to be the Baltic Sea. I think that this is the ultimate reason for differences between sets of cosmonyms in the Eastern Baltic area and in Central Europe. It is possible that the set of three interpretations of the celestial objects discussed above which have transEurasian spread and which most probably penetrated Europe from the East, included still another celestial image, i.e. the interpretation of the Big Dipper as a group of hunters who pursued game (Berezkin, 2005). In the Baltic area, however, this image was replaced with the image of the Great Dipper as a cart. References

Abramzon S.M. 1946 Ocherk kultury kirgizskogo naroda. Frunze: Izd. Kirgiz. liala AN SSSR. Aichenwald A.Yu., Petrukhin V.Ya., Helimski E.A. 1982 K rekonstruktsii mifologicheskikh predstavlenii finnougorskikh narodov. In Balto-slayanskie issledovaniya 1981 g. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 162192. Aktsorin V.A. 1991 Mariiskii folklor. Ioshkar-Ola: Mariisk. knizh. izd. Alekseyenko E.A. 1976 Predstavleniya ketov o mire. In Priroda i chelovek v religioznykh predstavleniyakh narodov Sibiri i Severa. Leningrad: Nauka, pp. 67105. Alekseyev N.A., Emelyanov N.V., Petrov V.T. 1995 Predaniya, legendy i mify sakha (yakutov). Novosibirsk: Nauka. Allen R.H. 1899 Star-Names and Their Meanings. New York, Leipzig: G.E. Stechert. Andree R. 1878 Ethnographische Parallelen und Vergleiche. Stuttgart: Maier. Anokhin A.V. 1997 Legendy i mify sedogo Altaya. Gorno-Altaisk: Ministerstvo kultury Respubliki Altai. Ariste P. 1974 Vadja muinasjutte ja muistendeid. Tid Eesti Filoloogia Alalt, No. 4: 334. Ariste P. 1977 Vadja muistendid. Tallinn: Valgus. Ariste P. 2005 Komi folklor. Tartu: Eston. literat. muzei. Arsenev V.K. 1995 Iz nauchnogo naslediya V.K. Arseneva. Kraevedchesky bull. Obschestvava izucheniya Sakhalina i Kurilskikh ostrovov, iss. 4: 151183.

Ashmarin N.I. 1984 Vvedenie v kurs chuvashskoi narodnoi slovesnosti. Cheboksary: NIYLIE, pp. 348. Azimov E.G., Tolstoy N.I. 1995 Astronomiya narodnaya. In Slavyanskie drevnosti, vol. 1. Moscow: Mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya, pp. 117119. Barag L.G. 1987 Bashkirskoe narodnoe tvorchestvo. Vol. 2: Predaniya i legendy. Ufa: Bashkir. knizh. izd. Batchelor J. 1927 Ainu Life and Lore. Tokyo: Kyobunkwan. Beckwith M. 1970 Hawaiian Mythology. Honolulu: Univ. of Hawaii Press. Belova O.V. 2004 Narodnaya Bibliya. Moscow: Indrik. Beretti N.I. 1929 Na Krainem Severo-Vostoke. Vladivostok: Vladivostok. otdel. gos. rus. geograf. obschestva. Berezkin Y.E. 2005 Cosmic hunt: Variants of Siberian North American myth. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, No. 2: 141150. Berezkin Y. 2006 The cosmic hunt: Variants of a Siberian North-American myth. Folklore (Tartu), vol. 31: 79100. Boas F. 1895 Indianische Sagen. Berlin: Asher. Boas F. 1916 Tsimshian mythology. In 31th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 291037. Boas F. 2002 Indian Myths and Legends from the North Paci c Coast of America. Vancouver: Talonbooks. Bogoras W. 1928 Chuckchee tales. Journal of American Folklore, vol. 41: 297452. Bogoraz V.G. 1939 Chukchi. Vol. 2: Religiya. Leningrad: Izd. Glavsevmorputi. Boneva T. 1994 Naroden svetogled. In Rodopi. Traditsionna duhovna i socialno-normativna kultura. Sofia: Etnografski Institut s Muzei, pp. 750. Brudnyi D., Eshmambetov K. 1968 Kirgizskie skazki. Moscow: Khudozh. literatura. Burykin A.A. 2001 Malye zhanry evenskogo folklora. St. Petersburg: Peterburg. vostokovedenie. Butanaev V.Y. 1975 Predstavlenie o nebesnykh svetilakh v folklore khakasov. Uchenye zapiski Khakasskogo Naucho-Issledovatelskogo Instituta yazyka, literatury i istorii. Ser. lolog., iss. 20, No. 3: 231240. Caspar F. 1975 Die Tupar. Berlin, NewYork: de Gruyter. Cenev G. 2004 Neboto nad Makedonija. Skopje: Mladinski kulturen centar. Chadaeva A.Ya. 1990 Drevnii svet. Skazki, legendy, predaniya narodov Khabarovskogo kraya. Khabarovsk: Knizh. izd.

110

Yu.E. Berezkin / Archaeology Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 37/4 (2009) 100113

Charnolusky V.V. 1930 Materialy po bytu loparei. Leningrad: Izd. Gos. rus. geograf. obschestva. Charnolusky V.V. 1962 Saamskie skazki. Moscow: Gos. Izd. khudozh. literatury. Chubinsky P.P. 1872 Trudy etnogra chesko-statisticheskoi ekspeditsii v Zapadnorusskii krai, vol. 1. St. Petersburg: Imper. rus. geograf. obschestvo. Denisov P.V. 1959 Religioznye verovaniya chuvash. Cheboksary: Chuvash. Gos. izd. Devyatkina T.P. 1998 Mifologiya mordvy. Saransk: Krasnyi Oktyabr. Dixon R.B. 1916 Oceanic Mythology. Boston: Marshall Jones. Dolgikh B.O. 1961 Mifologicheskie skazki i istoricheskie predaniya entsev. Moscow: Izd. AN SSSR. Dulzon A.P. 1966 Ketskie skazki. Tomsk: Izd. Tomsk. Gos. Univ. Dulzon A.P. 1972 Skazki narodov sibirskogo severa. Tomsk: Izd. Tomsk. Gos. Univ. Egorov N.I. 1995 Chuvashskaya mifologiya. In Kultura Chuvashskogo kraya, pt. 1. Cheboksary: Knizh. izd., pp. 109146. Egorov S.B. 2004 Predaniya, legendy i mifologicheskie rasskazy vepsov. In Mifologiya i religiya v sisteme kultury etnosa. St. Petersburg: Ros. etnograf. muzei, pp. 128129. Erddi J. 1968 Finnisch-Ugrische Gestirnnamen. Annales Universitatis Scientiarum Budapestiensis. Philologica, T. 8: 105121. Ergis G.U. 1967 Yakutskie skazki, vol. 2. Yakutsk: Knizh. izd. Ergis G.U. 1974 Ocherki po yakutskomu folkloru. Moscow: Nauka. Ernits T., Ernits E. 1984 Vadjalaste ja isurite thelepanekuid taevakehale kohta. Eesti Loodus, No. 9: 577581. Evseev V.Ya. 1981 Karelskoe narodnoe poeticheskoe tvorchestvo. Leningrad: Nauka. Fielstrup F.F. 2002 Iz obryadovoi zhizni kirgizov nachala XX veka. Moscow: Nauka. Galdanova G.R. 1987 Dolamaistskie verovaniya buryat. Novosibirsk: Nauka. Gamzatov G.G., Dalgat U.B. 1991 Traditsionnyi folklor narodov Dagestana. Moscow: Nauka. G adyszowa M. 1960 Wiedza ludowa o gwiazdoch. Wroclaw: Zaklad narodovyim ossoli skich. Golovnev A.V. 1995 Govoryaschie kultury. Traditsii samodiitsev i ugrov. Ekaterinburg: UrO RAN. Gura A.V. 1997 Simvolika zhivotnykh v slavyanskoi narodnoi traditsii. Moscow: Indrik.

Gura A.V. 2006 Lunnye pyatna: Sposoby konstruirovaniya mifologicheskogo teksta. In Slavyanskii i balkanskii folklor. Moscow: Indrik, pp. 460484. Gurvich I.S. 1948 Kosmogonicheskie predstavleniya u naseleniya Olenekskogo raiona. Sovetskaya etnogra ya, No. 3: 128131. Gurvich I.S. 1977 Kultura severnykh yakutov-olenevodov. Moscow: Nauka. Halidova M.R. 1984 Folklornye teksty. Primechaniya k folklornym tekstam. In Mifologiya narodov Dagestana. Makhachkala: Dagestan. lial AN SSSR. pp. 160187. Hallowell A.I. 1934 Some empirical aspects of northern Saulteaux religion. American Anthropologist, vol. 36: 389404. Hangalov M.N. 1960 Sobranie sochinenii, vol. 1, vol. 3. Ulan-Ude: Buryat. knizh. izd. Harva U. 1933 Altain Suvun Uskonto. Porvo, Helsinki: Werner Sderstrm. Helimski E.A. 1982 Samodiiskaya mifologiya. In Mify narodov mira. Moscow: Sovetskaya entsiklopediya, pp. 398401. Hirschberg W. 1929 Die Plejaden in Africa und ihre Beziehung zum Bodenbau. Zeitschrift fr Ethnologie, Bd. 61: 321337. Hasanova M.M., Pevnov A.M. 2003 Mify i skazki negidaltsev. Kyoto: Nakanishi Printing Co. Holmberg (Harva) U. 1927 The Mythology of All Races. Vol. 4: Finno-Ugric, Siberian. Boston: Marshall Jones. Homich L.V. 1974 Material po narodnym znaniyam nentsev. In Sotsialnaya organizatsiya i kultura narodov Severa. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 231248. Hose C., McDougall W. 1912 The Pagan Tribes of Borneo, vol. 2. London: MacMillan. Hudiakov I.A. 1969 Kratkoe opisanie Verkhoyanskogo okruga. Leningrad: Nauka. Ichon A. 1969 La Religion des Totonaques de la Sierra. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scienti que. Ishida E. 1998 Mat Momotaro. St. Petersburg: Peterburg. vostokovedenie. Its R.F. 1960 Myao. Istoriko-etnogra cheskii ocherk. Moscow, Leningrad: Izd. AN SSSR. Iuhma M.N. 1980 Zametki o chuvashskoi kosmonimii. In Onomastika Vostoka. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 264269. Jankovich N.Ch. 1951 Astronomija u predanima, obichajima i umotvorinama srba. Beograd: Srpska Akademija Nauka. Jochelson W. 1908 The Koryak. Leiden: E.J. Brill; New York: G.E. Stechert. Jochelson W. 1961 Kamchadal Texts. S-Gravenhage: Mouton.

Yu.E. Berezkin / Archaeology Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 37/4 (2009) 100113

111

Jones W. 1919 Ojibwa Texts. New York: Stechert. Karutc R. 1911 Sredi kirgizov i turkmenov Mangyshlaka. St. Petersburg: Izd. A.F. Devriena. Kerbelite B. 2001 Tipy narodnykh skazanii. St. Petersburg: Evropeisky dom. Koekemoer G.P. 2007 Lightning Design in an African Content. Pretoria a.o.: Tshwane Univ. of Technology. Konakov N.D., Ilina I.V., Limerov P.F., Ulyashev O.I., Shabaev Yu.P., Sharapov V.E., Vlasov A.N. 2003 Komi Mythology. Budapest: Akadmiai Kiad; Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society. Krappe A.H. 1938 La Gense des Mythes. Paris: Payot. Krappe A.H. 1940 The lunar frog. Folk-Lore, vol. 51: 161171. Kreinovich E.A. 1973 Nivhi. Moscow: Nauka. Kulemzin V.M., Lukina N.V. 1978 Materialy po folkloru khantov. Tomsk: Izd. Tomsk. Gos. Univ. Kuperjanov A. 2001 Linnutee. Metagused, No. 16: 107116. Kuperjanov A. 2003 Eesti taevas. Tartu: Eesti Folkloori Instituut. Lantis M. 1946 The social culture of the Nunivak Eskimo. In Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 35, pt. 3: 153323. Lszl G. 1975 Orosz-magyar kzisztr. Russko-vengerski slovar. Budapest: Akadmiai kiad. Laurinkene N. 2002 Predstavleniya o mesyatse i interpretatsiya vidimykh na nem pyaten v baltiiskoi mifologii. In Balto-slavyanskie issledovaniya, iss. 15. Moscow: Indrik, pp. 360385. Limerov P.F. 2005 Mu puksom Sotvorenie mira. Syktyvkar: Komi knizh. izd. Lopatin I.A. 1922 Goldy amurskie, ussuriiskie i sungariiskie. Vladivostok: Vladivostok. otdelenie Priamurskogo otdeleniya Rus. geograf. obschestva. Lukina N.V. 1990 Mify, predaniya, skazki khantov i mansi. Moscow: Nauka. Lundmark B. 1982 Sol-och mnkult samt astrala och celesta frestningar bland samerna. Umea: Vsterbotens Museum. MacDonald J. 1998 The Arctic Sky. Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum. Maksyutova N.H. 1973 Bashkirskaya kosmonimiya. In Onomastika Povolzhya. Ufa: Bashkir. Gos. Univ., pp. 382384. Mndoki L. 1963 Asiatische Sternnamen. In Glaubenswelt und Folklore der sibirischen Vlker. Budapest: Akadmiai Kiad, pp. 519 532. Marinov D. 2003 Narodna vjara. So a: Iztok-Zapad.

Mati etov M. 1973 Zvesdna imena in izro ila o zvezdah med slovenci. Traditiones. Zbornik Instituta za Slovensko Narodopisie, vol. 2: 4390. McClelland C. 1975 My Old People Say. An Ethnographic Survey of Southern Yukon Territory, pt. 1. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada. McIlwraith T.F. 1948 The Bella Coola Indians, vol. 2. Toronto: Univ. of Toronto Press. Meek C.K. 1931 A Sudanese Kingdom. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner. Miller D.S. 1997 Stars of the First People. Boulder: Pruett. Mladenova D. 2006 Zvezdnoto nebe nad nas. So a: Prof. Mariya Drinov. Moshkov V.A. 1900 Mirosozertsanie nashikh vostochnykh inorodtsev: Votyakov, cheremisov i mordvy. Zhivaya starina, God 10, iss. 1/2: 194 212. Munkcsi B. 1908 Die Weltgottheiten der Wogulischen Mythologie. Revue orientale pour les tudes ouralo-altaques, vol. 9. No. 3: 206 277. Munkcsi B. 1986 Wogulisches Wrterbuch. Budapest: Akadmiai Kiad. Nadrshina F.A. 1985 Bashkirskie predaniya i legendy. Ufa: Bashkir. knizh. izd. Napolskikh V.V. 1990 Paleoevropeiskii substrat v sostave zapadnykh nnougrov. In Uralo-Indogermanika: Balto-slavyanskie yazyki i problemy uralo-indoevropeiskikh svyazei, vol. 2. Moscow: Inst. slavyanovedeniya i balkanistiki AN SSSR, pp. 128134. Napolskikh V.V. 1992 Proto-uralic world picture: A reconstruction. In Northern Religions and Shamanism. Budapest: Akadmiai Kiad; Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, pp. 320. Napolskikh V.V. 1997 Vvedenie v istoricheskuyu uralistiku. Izhevsk: UrO RAN. Nelson E.W. 1899 The Eskimo about Bering Strait. Washington: Smithsonian Institution. Nevsky N.A. 1996 Luna i bessmertie. In Peterburg. vostokovedenie, iss. 8: 265301. Nenyang L.P. 1997 Khodyachii um naroda. Krasnoyarsk: Fond severnykh literatur HEGLEN. Nepokupnyi A.P. 2004 Ot prus. BAYTAN E.346 SITO k PAYCORAN E.6 PLEYADY kak sootvetstviyu lit. SIEEYNAS to je. In Baltoslavyanskie issledovaniya, iss. 16. Moscow: Indrik, pp. 6582. Niebrzegowska S. 1999 Gwiazdy w ludowym j zkowym obrazie wiata. In J zykowy obraz wita. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marie CurieSk odowskiej, pp. 137154. Nikolaeva I.A., Zhukova L.N., Demina L.N. 1989 Folklor yukagirov verkhnei Kolymy, pt. 1. Yakutsk: Yakut. Gos. Univ.

112

Yu.E. Berezkin / Archaeology Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 37/4 (2009) 100113

Nikonov V.A. 1973 Kosmonimiya Povolzhya. In Onomastika Povolzhya. Ufa: AN SSSR, pp. 373381. Nikonov V.A. 1980a Geografiya nazvanii Mlechnogo Puti. In Onomastika Vostoka. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 242261. Nikonov V.A. 1980b Materialy po kosmonimike Srednei Azii. In Onomastika Srednei Azii. Frunze: Ilim, pp. 290306. Nimuendaju C. 1951 The Tukuna. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press. Niskanen M. 2002 The origin of the Baltic-Finns from the physical anthropological point of view. The Mankind Quarterly, vol. 43, No. 2: 121153. Novikova K.A. 1987 Evenskie skazki, predaniya i legendy. Magadan: Knizh. izd. Ostermann H. 1942 The Mackenzie Eskimos. Copenhagen: The Fifth Thule Expedition. Ostermann H. 1952 The Alaskan Eskimos as Described in the Posthumous Notes of Dr. Knud Rasmussen. Copenhagen: The Fifth Thule Expedition. Ovchinnikov M.P. 1897 Iz materialov po etnografii yakutov. Etnograficheskoe obozrenie, No. 3: 148184. Pechul-Loesche E. 1907 Volkskunde von Loango. Stuttgart: Strecker & Schrder. Peebo K., Peegel J. 1989 Igal puul oma juur. Murdetekste Jakob Hurde kogust. Tallinn: Eesti raamat. Pelikh G.I. 1972 Proishozhdenie selkupov. Tomsk: Izd. Tomsk. Gos. Univ. Pilsudski B. 1912 Ainu folk-lore. Journal of American Folklore, vol. 25: 7286. Pilsudski B. 1991 Folklor ainov. Kraevedchesky bulleten Obschestva izucheniya Sakhalina i Kurilskikh ostrovov, iss. 3: 6984. Pogodin A. 1895 Kosmicheskie legendy baltiiskikh narodov. Zhivaya starina, God 5, iss. 3/4: 428448. Podmaskin V.V. 1991 Dukhovnaya kultura udegeitsev. Vladivostok: Izd. Dalnevostoch. Gos. Univ. Podmaskin V.V. 2006 Narodnye znaniya tunguso-manchzhurov i nivkhov. Vladivostok: Dalnauka. Popov A.A. 1949 Materialy po istorii religii yakutov byvshego Vilyuiskogo okruga. Moscow, Leningrad: Izd. AN SSSR, pp. 255323. (Sb. MAE; vol. 11). Popov A.A. 1984 Nganasany. Leningrad: Nauka. Porotov G.G., Kosygin V.V. 1969 V strane Kutkhi. Petropavlovsk-Kamchatski: Dalnevostoch. knizh. izd. Potanin G.N. 1881 Ocherki Severo-Zapadnoi Mongolii, iss. 2. St. Petersburg: [Tip. Kirshbauma].

Potanin G.N. 1883 Ocherki Severo-Zapadnoi Mongolii, iss. 4. St. Petersburg: [Tip. Kirshbauma]. Potanin G.N. 1893 Tangutsko-tibetskaya okraina Kitaya i Tsentralnaya Mongoliya, vol.2. St. Petersburg: [Tip. A.S. Suvorina]. Potanin G.N. 1919 Mongolskie skazki i predaniya. Zapiski Semipalatinskogo podotdeleniya Zapadno-Sibir. otdeleniya Rus. geograf. obschestva, iss. 13: 197. Pustylnik I. 2002 Astronomicheskoe nasledie drevnikh estov. In Astronomiya drevnikh obschestv. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 283285. Rasmussen K. 1930 Observations on the Intellectual Culture of the Caribou Eskimos. Copenhagen: The Fifth Thule Expedition. Rassadin V.I. 1996 Legendy, skazki i pesni sedogo Sayana. Tofalarskii folklor. Irkutsk: Komitet po kulture Irkutsk. oblast. admin. Ray C., Stevens J. 1971 Sacred Legends of the Sandy Lake Cree. Toronto: McClelland & Steward. Reed A.W. 1999 Maori Myths and Legendary Tales. Aukland, Sydney, London, Cape Town: New Holland Publishers. Rodd F.R. 1926 People of the Veil. London: MacMillan & Co. Rodionov V.G. 1982 K obrazu lebedya v zhanrakh chuvashskogo folklora. In Chuvashskii folklor. Cheboksary: NIYLIE, pp. 150170. Rudenko S.I. 1955 Bashkiry. Moscow, Leningrad: Izd. AN SSSR. Rut M.E. 1987 Russkaya narodnaya astronimiya. Sverdlovsk: Ural. Gos. Univ. Rychkov K.N. 1922 Eniseiskie tungusy. Zemlevedenie, bk. 1/2: 69106. Sanzheev G.D. 1930 Darkhaty. Leningrad: Izd. AN SSSR. Schefold R. 1988 Lia: Das gro e Ritual auf den Mentawai-Inseln. Berlin: Dieter Reimer Verlag. Schwab G. 1947 Tribes of Liberian Hinterland. Cambridge: Peabody Museum. Seroshevsky V.L. 1896 Yakuty, vol. 1. St. Petersburg: Imper. Rus. geograf. obschestvo. Sharakshinova N.O. 1980 Mify buryat. Irkutsk: Vostochno-Sibir. knizh. izd. Sidelnikov V.M. 1962 Kazakhskie skazki, vol. 2. Alma-Ata: Kazakh. Gos. Izd. khudozh. literatury. Simchenko Y.B. 1996 Traditsionnye verovaniya nganasan, pt. 1. Moscow: IEA RAN. Sirotkin M.Ya., Ivanov M.I. 1970 Chuvashi, pt. 2. Cheboksary: Knizh. izd. Smith W.C. 1925 The Ao Naga Tribe of Assam. London: MacMillan & Co.

Yu.E. Berezkin / Archaeology Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 37/4 (2009) 100113

113

Speck F.G. 1915 Myths and Folklore of the Timiskaming Algonquin and Timagami Ojibwa. Ottawa: Canada Department of Mines. Spieth J. 1906 Die Ewe-Stmme. Berlin: Reimer. Steinitz W. 1966-1993 Dialektologisches und etymologisches Wrterbuch der ostjakischen Sprache, Lfg. 115. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. Sullv J., Kauksi ., Kivupuu M., Reimann N., Hagu P. 1955 ABC kiroppus ja lugmik algkooli latsil. Vro: Vro Instituut ja Vro Selts. Svyatsky D.O. 1961 Ocherki istorii astronomii v Drevnei Rusi. Istorikoastronomicheskie issledovanija, iss. 7: 75128. Swanton J.R. 1908a Haida Texts, Masset Dialect. In Jesup North Pacific Expedition, Publ. 10. Leiden: E.J. Brill; NewYork: G.E. Stechert, pp. 273812. Swanton J.R. 1908b Social conditions, beliefs, and linguistic relationship of the Tlingit Indians. In 26th Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 391485. Teit J.A. 1898 Traditions of the Thompson River Indians of British Columbia. Boston, NewYork: The American Folklore Society. Teit J.A. 1909 The Shuswap. Memoires of the American Museum of Natural History, vol. 4: 443813. Mladshaya Edda. 1970 Leningrad: Nauka. Thompson T., Egesdal S.M. 2008 Salish Myths and Legends. Lincoln, London: Univ. of Nebraska Press. Toivonen Y.H. 1937 Pygmen und Zugvgel. Alte kosmologische Vorstellungen. Finnisch-Ugrische Forschungen, Bd. 24, H. 1/3: 87126. Tolokonsky N. 1914 Yakutskie poslovitsy, zagadki, svyatochnye gadaniya, obryady, poverya, legendy i drugoe. Irkutsk: [Tip. t-va M.P. Okunev i K.]. Tuchkova N.A. 2004 Mifologiya selkupov. Tomsk: Izd. Tomsk. Gos. Univ. Urazaleev R. 2005 Natsionalnyi folklor sibirov Srednego Priirtyshya. URL: http://sybyrlar.narod.ru/folklor.html. (30.09.2009). Vaik nas J. 1999 Etnoastronomia litewska. Etnolingwistika, vol. 11: 165 175. Vaik nas J. 2004 Narodnaya astronomiya belorussko-litovskogo pogranichya. In Balto-slavyanskie issledovaniya, iss. 16. Moscow: Indrik, pp. 168179. Vaik nas J. 2006 The Moon in Lithuanian folk tradition. Folklore (Tartu), vol. 32: 157184. Valeev F.T. 1976 O religioznykh predstavleniyakh zapadnosibirskikh tatar. In Priroda i chelovek v religioznykh predstavleniyakh narodov Sibiri i Severa. Leningrad: Nauka, pp. 320331.

Vardugin V.I. 1996 Mify drevnei Volgi. Saratov: Nadezhda. Vasilevich G.M. 1936 Materialy po evenkiiskomu (tungusskomu) folkloru. Leningrad: Izd. Inst. narodov Severa. Vasilevich G.M. 1959 Rannie predstavleniya o mire u evenkov. TIE, iss. 51: 157 192. Vasilevich G.M. 1969 Evenki. Leningrad: Nauka. Vasiliev M. 1907 Religioznye verovaniya cheremis. Ufa: [Gub. tip.]. Vathanaprida S. 1994 Thai Tales. Englewood: Libraries Unlimited. Vereschagin G.E. 1995 Votyaki Sosnovskogo kraya. Izhevsk: UrO RAN. Vladykin V.E. 1994 Religiozno-mifologicheskaya kartina mira udmurtov. Izhevsk: Udmurtiya. Volpati C. 1932 Nomi romanzi degli astri Sirio, Orione, le Pleiadi e le Jadi. Zeitschrift fr romanische Philologie, Bd. 52: 151211. Volpati C. 1933a Nomi romanzi delle Orse, Boote, Cigno e altre costellazioni. Zeitschrift fr romanische Philologie, Bd. 53: 449507. Volpati C. 1933b Nomi romanzi della Via Lattea. Revue de linguistique romane, No. 9: 151. Vorobyev N.I., Hisamutdinov G.M. 1967 Tatary Srednego Povolzhya i Priuralya. Moscow: Nauka. Voskoboinikov M.G. 1960 Evenkiiskii folklor. Leningrad: Uchpedgiz. Voskoboinikov M.G. 1967 Folklor evenkov Pribaikalya. Ulan-Ude: Buryat. knizh. izd. Wichmann Y. 1987 Wotjakischer Wortschatz. Helsinki: Socit Finnoougrienne. Williamson R.W. 1933 Religious and Cosmic Beliefs of Central Polynesia, vol. 1. Cambridge: Univ. Press. Wolf W. 1929 Der Mond in deutschen Volksglauben. Bhl (Baden): Konkordia. Zhukovskaya N.L. 1988 Darkhaty. In Narody mira. Moscow: Sovet. entsiklopediya. Zolotnitsky N.I. 1874 Otryvki iz chuvashsko-russkogo slovarya. No. 14: Chuvashskie nazvaniya Boga, neba i svetil nebesnykh. Kazan: [Gub. tip.]. Zsigmond C. 2003 Popular cosmology and beliefs about celestial bodies in the culture of the Hungarians from Romania. Acta Ethnographica Hungarica, vol. 48, No. 3/4: 421439.

Received April 18, 2008.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Chisholm EddaDocument217 pagesChisholm EddaOthroerir100% (3)

- Celtic Dreams & EuropeDocument8 pagesCeltic Dreams & Europeork6821No ratings yet

- Carnivale - Pitch DocumentDocument61 pagesCarnivale - Pitch Documentszaman10No ratings yet

- Red ViennaDocument281 pagesRed ViennaphilipglassNo ratings yet

- Crawley Tree of LifeDocument101 pagesCrawley Tree of Lifeszaman10No ratings yet

- Conflict in Colonial OrinocoDocument44 pagesConflict in Colonial OrinocoEmiliano GarciaNo ratings yet

- Indian Art History TimelineDocument1 pageIndian Art History TimelinePranit Rawat100% (1)

- Brooks Uluru InvertedDocument7 pagesBrooks Uluru Invertedszaman10No ratings yet

- Eric - Csapo PublicationsDocument2 pagesEric - Csapo Publicationsszaman10No ratings yet

- Schneider CosmogonicTheater Public Performance in Evolution ControversiesDocument158 pagesSchneider CosmogonicTheater Public Performance in Evolution Controversiesszaman10No ratings yet

- Fox Explorations in Semantic ParallelismDocument448 pagesFox Explorations in Semantic Parallelismszaman10No ratings yet

- Abbie Australian Aborigine 1Document14 pagesAbbie Australian Aborigine 1szaman10No ratings yet

- Museum of Bihar in PatnaDocument3 pagesMuseum of Bihar in PatnaAbhishekGaurNo ratings yet

- Cultural Identity in Monica Ali - S Brick Lane A Bhabhian PerspectiveDocument16 pagesCultural Identity in Monica Ali - S Brick Lane A Bhabhian PerspectiveMahdokht RsNo ratings yet

- Poem AnalysisDocument6 pagesPoem AnalysisSanjukta ChaudhuriNo ratings yet

- Conklin 1978 (The Revolutionary Weaving Inventions of The Early Horizon)Document19 pagesConklin 1978 (The Revolutionary Weaving Inventions of The Early Horizon)José A. Quispe HuamaníNo ratings yet

- Next Edition: Councillor Christine Henderson, Dot Pollard and Reverend Anne MckennaDocument12 pagesNext Edition: Councillor Christine Henderson, Dot Pollard and Reverend Anne MckennaAmityNo ratings yet

- A Level Urdu Specification11 PDFDocument56 pagesA Level Urdu Specification11 PDFMohammad HasnainNo ratings yet

- Arduin Eternal - Country of ChorynthDocument15 pagesArduin Eternal - Country of ChorynthT100% (1)

- 1st Summative USCPDocument2 pages1st Summative USCPNezel100% (2)

- Synthesis PaperDocument6 pagesSynthesis Paperapi-404874946No ratings yet

- KaveripoompatinamDocument2 pagesKaveripoompatinamSindhu SundaraiyaNo ratings yet

- Hip HopDocument29 pagesHip HopJohn WickNo ratings yet

- MestizoDocument3 pagesMestizoEva GalletesNo ratings yet

- Developing Culturally Responsive Programs to Promote International Student Adjustment: A Participatory Approach. By Laura R. Johnson, Tanja Seifen-Adkins, Daya Singh Sandhu, Nadezda Arbles, & Hitomi Makino, pp. 1865–1878 [PDF, Web]Document14 pagesDeveloping Culturally Responsive Programs to Promote International Student Adjustment: A Participatory Approach. By Laura R. Johnson, Tanja Seifen-Adkins, Daya Singh Sandhu, Nadezda Arbles, & Hitomi Makino, pp. 1865–1878 [PDF, Web]STAR ScholarsNo ratings yet

- Wallet Phrase CardDocument2 pagesWallet Phrase CardRenie ArcegaNo ratings yet

- Address of The CandidateDocument201 pagesAddress of The CandidateKathleen MaeNo ratings yet

- Lalita Ashtottara Sata Namaavali in KannadaDocument5 pagesLalita Ashtottara Sata Namaavali in Kannadashiva kumarNo ratings yet

- NEW YORK CITY Lesson Plan Test b1Document7 pagesNEW YORK CITY Lesson Plan Test b1NataliaNo ratings yet

- The Genealogy of Japanese Immaturity PDFDocument12 pagesThe Genealogy of Japanese Immaturity PDFjorgeNo ratings yet

- The World of Piano Competitions Issue 1 2019Document44 pagesThe World of Piano Competitions Issue 1 2019buenamadreNo ratings yet

- Avenue Q CastDocument1 pageAvenue Q Castapi-173052549No ratings yet

- Virtual VacationDocument2 pagesVirtual Vacationapi-261853457No ratings yet

- English Commentary LunalaeDocument4 pagesEnglish Commentary LunalaeAkshat JainNo ratings yet

- Division Advisory No. 266 S. 2023Document82 pagesDivision Advisory No. 266 S. 2023Jussa Leilady AlberbaNo ratings yet

- Cuadernillo de Preguntas: COMPRENSIÓN DE LECTURA (Duración: 1 Hora)Document4 pagesCuadernillo de Preguntas: COMPRENSIÓN DE LECTURA (Duración: 1 Hora)Maria BNo ratings yet

- Individualism in American CultureDocument3 pagesIndividualism in American CultureMadalina CojocariuNo ratings yet

- Schein (1984) - Coming To A New Awareness of Organizational CultureDocument2 pagesSchein (1984) - Coming To A New Awareness of Organizational CulturenewsNo ratings yet

![Developing Culturally Responsive Programs to Promote International Student Adjustment: A Participatory Approach. By Laura R. Johnson, Tanja Seifen-Adkins, Daya Singh Sandhu, Nadezda Arbles, & Hitomi Makino, pp. 1865–1878 [PDF, Web]](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/393843061/149x198/0939085fd3/1542865274?v=1)