Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Why Greater Equality Strengthens Society - The Nation

Uploaded by

readthisnotthatOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Why Greater Equality Strengthens Society - The Nation

Uploaded by

readthisnotthatCopyright:

Available Formats

The Nation.

Why Greater Equality Strengthens Society

by SaM PIzzIGaTI

or American progressives, looking at Britain can sometimes seem like looking in a mirror. The British face essentially the same economic crisis we do. A neverending recessionand never-ending windfalls for CEOs. Austerity budgets. Rising poverty. Young people without a future. Old people without security. But this mirror analogy cracks as soon as we start comparing progressive agendas. Some top priorities on Americas progressive to-do list simply dont show up on the British version. Theres no mystery why: British progressives already have in place a good chunk of what were still desperately seeking. A healthcare system that ices out profiteering insurers? Britain has one. Progressive tax rates up to 50 percent on income over $250,000? Check. A financial transactions tax on stock trades? The British even have that, too. These contrasts should give us pause. If the British are hurting even after achieving so much of what were seeking, were clearly not seeking enough. Maybe our transatlantic colleagues can help us here. What are they seeking? Can their visionsand strategiesinform and embolden ours? I spent some time in London in Octoberjust after Occupy Wall Street launched in Manhattan and just before British Occupiers set up shop at St. Pauls Cathedralposing these questions to an array of thoughtful campaigners against Britains top 1 percent. I didnt expect these activists to have any secret for plutocracy-busting success. But I was hoping to find some emphasis that I hadnt expected, and I found plenty. Take orientation, for instance. Unlike us, British progressives are not looking backward for ideas and inspiration. We do that all the time: contrasting Obama with FDR, demanding new CCCs, coveting New Deal tax rates. Britain has a similar heroic progressive pastthe years right after World War II, when the Labour Party, steeled by sacrifice and solidarity, laid the foundation for the modern British welfare state. Conventional Labour Party politicos still try to resuscitate that 1945 moment, notes Neal Lawson, the chair of Compass,

Britains largest independent progressive pressure group. But British progressives dont see that moment as a blueprint for the future, because the conditions that made it possiblean economy built on mass manufacturing, a heavily unionized working class, cold war rivalryno longer exist. British progressives also have a deeper point to make: the basic blueprint of their heroic past may be inherently flawed. The activists I met, young and old alike, sprinkled their analyses with dismissiveand disconcertingreferences to tax and spend policies. How could they, I wondered, so casually accept a basic conservative frame? Didnt they realize they were legitimizing a right-wing epithet? I eventually caught on. They dont consider tax and spend any sort of social engineering outrage. They simply consider it inadequate to the task of creating the just and sustainable society our future demands. Such policies take the corporate economy as a givenand accept that it will help some and hurt others. The tax-and-spend antidote to this inequality: tax the fortunate to fund programs that boost the disadvantaged. This notion of the redistributive state drove Labour Party policy from the mid-twentieth century to the 1990s, when New Labour added a perverse twist. To regain power in Thatcherite Britain, Tony Blair and friends argued, Labour would have to soothe the City, Britains Wall Street. New Labour, they insisted, could comfort the bankers and help poor people at the same timeby freeing the City to rev up the economy. If the City boomed, even modest levies on the rich would raise enough revenue to end child poverty. In effect, Blair was positioning British high finance as a cash cow for an improved welfare state, says Stewart Lansley, an award-winning analyst of British poverty. Once elected in 1997, New Labour followed through on this City soothing. Light touch regulation soon had the economy roaringand made the rich phenomenally richer. Growing inequality didnt seem to matter as long as poor people were getting some help. As Blair strategist Peter Mandelson famously put it: We are intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich, as long as they pay their taxes.

REUTERS/Toby MElvillE

12

The Nation.

December 26, 2011

Of course, growing inequality did matter. In Britain, as in the United States, the chase after grand fortune would crash the economy. The poor would be worse off. The rich, after a brief dip, would rebound.

he lesson in all this? We need to attack inequality at its rootsand not depend on redistribution at the end, says Faiza Shaheen, a young economist at Londons innovative New Economics Foundation. Shaheen makes a medical analogy. Over time, she explains, viruses can develop resistance to antiviral medications. The rich, over time, develop resistance to redistributive taxes. They use their wealth and power to carve out loopholes and lower rates. Their fortunes balloon. Inequality grows. Smart public health officials stress prevention. Smart social and economic policy, says Shaheen, would stress prevention, too. We shouldnt rely on our ability to tax income that concentrates at the top. We should prevent that income from concentrating in the first place. And the front line of any prevention struggle should be the corporate enterprise, where power-suited 1 per-

British progressives consider tax and spend policies inadequate to the task of creating a just and sustainable society.

centers are raking off a fantastically disproportionate share of the wealth our economies generate. Inequality simply matters too much, sums up Shaheen, to let it dig in. British progressives were never comfortable with New Labours intense relaxation about people getting rich. But they now have much more evidence to back up their instinctand a renewed sense of egalitarian confidence. Both the evidence and the confidence come in large part from a remarkable 2009 book, The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger, by British epidemiologists Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett.The authors explore the impact of inequality on modern societies and demonstrate in graphic detail that people in more equal nations live longer, healthier and happier lives. Wilkinson and Pickett took their stunning data slides to cities across Britain. If Britain had levels of inequality as low as those of Scandinavia and Japan, they explained, British murder rates would drop by half, mental illness by two-thirds, teen births by 80 percent. The Spirit Level became a bestseller, and two advocacy groups have formed to deepen its impact. One Society reaches out to policy-makers; the Equality Trust helps inspired readers organize locally. The campaigns seem to be having an impact. The Equality Trust has so far persuaded eighty-seven members of Parliament to sign a pledge to make Britain a more equal society. In the run-up to the May 2010 general election, the leaders of

Sam Pizzigati edits Too Much, an Institute for Policy Studies weekly on inequality and excess. His new book, The Rich Dont Always Win: The Forgotten Triumph Over Plutocracy That Created the American Middle Class (Seven Stories), will appear after the 2012 elections.

Britains three major parties jostled to claim the fairness mantle. Conservative Party leader David Cameron even favorably cited The Spirit Level. We all know in our hearts, he opined, that, as long as there is deep poverty living systematically side by side with great riches, we all remain the poorer for it. After the 2010 elections, Cameron, the new prime minister, moved quickly to burnish his fairness credentials. With considerable fanfare, he tabbed Will Hutton, a respected journalist and foundation executive, to conduct an official policy review of pay disparities within the public sector. The interim report pleasantly surprised progressives who considered the review little more than a cynical ploy to buttress right-wing claims about public sector fat cats. Hutton documented that public officials make up only a minuscule sliver of the top 1 percent. The private sector, he added, needs to get a grip on the CEO pay arms race in the name of a better, more productive and fairer capitalism. The recommendations of the final Hutton Review, released this past March, were toned down. But they sank out of sight anyway, as Conservatives prone to demonizing the public sector saw no value in them. British progressives, meanwhile, had already started down a different road. In August 2009 Compass rallied 100 progressive leaders and called on the then-ruling Labour Party to establish a High Pay Commission that would aim to help ensure that out of control rewards could never again fuel the excessive risk taking that can melt an entire economy. Labour ignored the call, and after the elections Compass decided to move ahead on its own. With foundation support, the group filled an independent High Pay Commission with a blueribbon cross-section of British civil society, business and labor. The new commission, chaired by a former Financial Times editor, quickly gained a high media profile. A poll unveiled at the launch revealed that only 1 percent of the public believed that CEOs should be making more than 4 million (about $6.4 million) a year. Britains top 100 execs were then averaging more than $7.7 million. A follow-up data release from this past spring divulged that in 2010 execs at bailed-out British banks took home more than double their compensation a decade earlier. We cant reverse this trend overnight, the commissions lead staffer, Zoe Gannon, admitted in October. But the commission, Gannon added, could challenge the assumptions framing the mainstream debate, and thats just what the commissions final report, released November 22, has done.

ntil now, in both Britain and the United States, the executive pay debate has revolved around protecting and empowering shareholdersso poorly performing CEOs dont walk away rich while share prices plummet. British lawmakers gave shareholders say on pay the right to take advisory votes on executive paynearly a decade ago. US shareholders didnt get that right until the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation passed last year. But say on pay hasnt ended runaway compensation in Britain, where executive bonuses have nearly tripled over the past

14

The Nation.

December 26, 2011

decade. Top exec pay at banking giant Barclays has gone from thirteen times average British worker pay in 1980 to 169 times the worker average today. Such stratospheric increases, the High Pay Commission report charges, are damaging the UK economyundermining productivity, distorting markets, draining talent from key sectors. Expecting only shareholders to end this executive excess makes no sense, the commission suggests, not when the excess imperils more than shareholders. We have all become stakeholders in the decisions that determine the distribution of corporate rewards. The report recommends a series of steps to empower this broader community of stakeholders. Real employees, not just CEO cronies, should sit on corporate board remuneration committees. And full disclosure must accompany every facet of the processnot just so shareholders can protect their investment but so that workers and consumers can mobilize and press against enterprises that contribute to greater inequality. How can stakeholders gauge corporate contributions to inequality? The commission recommends that every British

Mandatory disclosure of pay ratios would expose companies that contribute to inequality while boosting ethical narrow gap employers.

corporation be required to publish the ratio between top executive and median worker compensation. Pay ratios have been floating around British egalitarian circles for quite some time. Various progressive groups have called for a maximum wage set as a multiple of worker pay. David Cameron even asked his Hutton Review to consider limiting top pay in the public sector to twenty times bottom pay. That review, in the end, rejected ratio limits but endorsed disclosure, in both the public and private sectors. Progressive groups like One Society see much more organizing potential in pay ratios than in traditional tax and spend, mainly because three decades of right-wing pounding against government have left the public deeply wary about expanding the welfare state. Polls, by contrast, show widespread interest in limiting pay gaps. The idea that we have a lot of people at the top who get more than they earn and a lot of people at the bottom who earn more than they get, says One Societys Duncan Exley, has quite strong support. One Society and its sister campaign, the Equality Trust, like to invert the typical ratio formula. Instead of talking about executive pay as a huge multiple of worker pay, they stress worker wages as a tiny fraction of executive pay. Why the inversion? Talking in terms of multiples, explains Equality Trusts Bill Kerry, can play into the inequality apologist narrative. Corporations have no choice, CEO pay defenders argue; they have to pay high multiples to attract talent. But inverting the ratio forces apologists to defend the morally indefensible notion that workers and their work have virtually no value.

ritish activists have begun building a pay-ratio politics at the local level, too. Last year the Greater London Authority pledged to reduce the high-to-low pay gap to no more than 20 times, with a long term goal of no more than 10 times. Equality Trust activists are running a My Fair London campaign to tighten that commitment. Another locality is moving more boldly. Islington, a London borough that sits next to the financial district, formally adopted a ten-times pay commitment in early October. This past summer, the borough slashed the salary of its incoming chief executive by nearly 25 percent, to 160,000 (about $250,000). Its hard to lecture others about inequality, says Islington Labour Party council member Andy Hull, if we dont have our own house in order. Islingtons Labour Party activists won a council majority last year on a promise to narrow inequality in a jurisdiction home to both latte-sipping bank execs and 45 percent child poverty. To start making good on that promise, the new Labour majority created a Fairness Commission to prepare a gap-narrowing plan and invited Britains most celebrated egalitarian, Richard Wilkinson, to chair the panel. Hull served as vice chair, and his fellow commissioners even included the CEO of the Islington Chamber of Commerce. The Fairness Commission held a series of public hearings in sites as disparate as a former crackhaven housing project and the swank offices of an elegant Islington-based global law firm. Its final report, Closing the Gap, appeared in June, just as national austerity cutbacks were kicking in. In this climate, the panel argued, achieving greater equality has become more important than ever. Volunteer initiatives expected to pick up the slack can never gain traction in localities where social cohesion and community life have weakened under the impact of widening income differences. A local government, the panel acknowledged, has limited clout; it cant force private employers to narrow pay differentials. But a public employer like Islington can ensure its lowest-paid employees a living wage, limit pay ratios and encourage the councils 10,000 private employers to adopt similar benchmarks. The Islington council is implementing these proposals. Local employers who honor the fairness agenda will earn a kitemarka recognition symbol they can publicly display. And over the next year, Hull and his colleagues will be leading citizen delegations to meet with Islingtons 100 largest private employersa cohort that includes Arsenal, one of the worlds five top pro soccer franchises, where janitors make less than the London living wage. Imagine the pay differential there, says Hull. Im not kidding myself that were going to get Arsenal to agree to a oneto-ten pay ratio anytime soon. But Id like to think we could get their cleaners enough to have dignity. Other localities are ramping up fairness commissions on the Islington model. The wage ratios that emerge from these efforts, Equality Trusts Bill Kerry believes, will help stimulate an ethical consumer movement that champions narrow gap employers. Every consumer, in effect, will be able to become an advocate for more equitable workplaces. Maybe every taxpayer, too. The pounds average British fami-

December 26, 2011

The Nation.

15

lies pay in taxes regularly pour into the coffers of private contractors that lavish windfalls on their top execs. At Serco, a corporate giant that gets more than 90 percent of its revenue from public bodies, the CEO last year took in over 3.1 million (about $5 million). Public bodies can end these taxpayer subsidies for inequality by giving preferential treatment to narrow gap contractors, and by denying tax dollars to those with overpaid executives. They can even extend this denial to corporations that line up for tax incentives and subsidies. Leveraging the public purse in this way would require, as a first step, the mandatory disclosure of corporate pay gaps that progressives have been pressing for and the High Pay Commission report has recommended. Ironically, that mandate already exists, at least on paper, in the United States. Last year New Jersey Senator Bob Menendez outflanked corporate lobbyists and slipped into the Dodd-Frank bill a provision that requires publicly traded companies to reveal their CEOmedian worker pay ratios every year. The Securities and Exchange Commission hasnt yet articulated how it will enforce this mandate, and embarrassed corporate shills are pushing hard to get it watered downor repealed in Congress. So Americans have a ratio disclosure mandate with no political momentum behind itand no vision for making the most of it. Brits have no mandate but momentum and vision. They see how organizing consumer and procurement battles over pay ratios could help bring about a sea change in Britains polite political culture. Excessively high incomes, as the British Archbishop of York John Sentamu recently wrote, have to become as socially unacceptable as racism and homophobia. Thats not to say that British progressives feel they can tame inequality one enterprise at a time. Im patient, Compass chair Neal Lawson says with a smile, but not that patient. Compass recently released a planendorsed by 100 British economists that sets forth not just an alternative to the austerity cuts that hundreds of thousands of British workers protested on November 30 but an alternative to business as usual and all that means for growing inequality, climate change, and peoples well-being. To go beyond this business as usual, the plan demands national action on everything from creating a publicly accountable British investment bank to forging a new progressive tax structure. Such action, Compass continues, has to prioritize fairness over greed, the needs of productive capital over finance capital, the long term over the short, and the needs of people and the planet over the excessive and undeserved profits of a few. None of the British thinkers and activists I met see these reforms as imminent. But most share a feeling that the public must begin to see some indication that progressive approaches can actually curb the inequalities so rampant around them. Without this sense of progress, the danger remains that growing social cynicismparticularly among the youngmay erupt in more outbreaks of looting and burning, as London experienced this past summer. And then what? The response to crisis doesnt have to be left-wing, notes George Irvin, a retired British progressive economist steeped in continental European history. It can be right-wing as well. And incredibly ugly. Unless we get our acts togetheron both sides of the pond. n

THE NATION INSTITUTE and the PUFFIN FOUNDATION salute the 2011 winner of The Puffin/Nation Prize for Creative Citizenship

Playwright . Screenwriter . Activist

Tony Kushner

Previous Winners:

Robert Moses Dolores Huerta David Protess Barbara Ehrenreich Jonathan Kozol Amy Goodman Michael Ratner Van Jones Jim Hightower Cecile Richards Bill Mckibben

The Puffin/Nation Prize carries a $100,000 cash award and is given annually to an American citizen who has challenged the status quo through distinctive, courageous, imaginative, socially responsible works of significance. This is the first year in the history of the Prize that there are two prize recipients.

For more information visit: www.nationinstitute.org/puffinnation

Puffin/Nation Prize for Creative Citizenship The Nation Institute, 116 East 16th Street, 8th Floor, New York, NY 10003.

PN AD saluting 2011_01.indd 1

12/5/11 1:54 PM

You might also like

- Junk PoliticsDocument9 pagesJunk PoliticsreadthisnotthatNo ratings yet

- Politics of PLanned ParenthoodDocument12 pagesPolitics of PLanned ParenthoodreadthisnotthatNo ratings yet

- Dream MachineDocument8 pagesDream MachinereadthisnotthatNo ratings yet

- House PerfectDocument12 pagesHouse PerfectreadthisnotthatNo ratings yet

- Politics of PLanned ParenthoodDocument12 pagesPolitics of PLanned ParenthoodreadthisnotthatNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Application Form For Subscriber Registration: Tier I & Tier II AccountDocument9 pagesApplication Form For Subscriber Registration: Tier I & Tier II AccountSimranjeet SinghNo ratings yet

- InvoiceDocument2 pagesInvoiceiworldvashicmNo ratings yet

- 2023 DPWH Standard List of Pay Items Volume II DO 6 s2023Document103 pages2023 DPWH Standard List of Pay Items Volume II DO 6 s2023Alaiza Mae Gumba100% (1)

- Presentation NGODocument6 pagesPresentation NGODulani PinkyNo ratings yet

- DX210WDocument13 pagesDX210WScanner Camiones CáceresNo ratings yet

- BS Irronmongry 2Document32 pagesBS Irronmongry 2Peter MohabNo ratings yet

- Net Zero Energy Buildings PDFDocument195 pagesNet Zero Energy Buildings PDFAnamaria StranzNo ratings yet

- Business Economics - Question BankDocument4 pagesBusiness Economics - Question BankKinnari SinghNo ratings yet

- A Study On Green Supply Chain Management Practices Among Large Global CorporationsDocument13 pagesA Study On Green Supply Chain Management Practices Among Large Global Corporationstarda76No ratings yet

- Presentation On " ": Human Resource Practices OF BRAC BANKDocument14 pagesPresentation On " ": Human Resource Practices OF BRAC BANKTanvir KaziNo ratings yet

- Pandit Automotive Pvt. Ltd.Document6 pagesPandit Automotive Pvt. Ltd.JudicialNo ratings yet

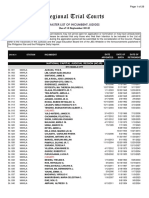

- Regional Trial Courts: Master List of Incumbent JudgesDocument26 pagesRegional Trial Courts: Master List of Incumbent JudgesFrance De LunaNo ratings yet

- Competition Act: Assignment ONDocument11 pagesCompetition Act: Assignment ONSahil RanaNo ratings yet

- Regional Policy in EU - 2007Document65 pagesRegional Policy in EU - 2007sebascianNo ratings yet

- Democratic Developmental StateDocument4 pagesDemocratic Developmental StateAndres OlayaNo ratings yet

- Patent Trolling in IndiaDocument3 pagesPatent Trolling in IndiaM VridhiNo ratings yet

- PT Berau Coal: Head O CeDocument4 pagesPT Berau Coal: Head O CekresnakresnotNo ratings yet

- DuPont Analysis On JNJDocument7 pagesDuPont Analysis On JNJviettuan91No ratings yet

- Bill CertificateDocument3 pagesBill CertificateRohith ReddyNo ratings yet

- Production Planning & Control: The Management of OperationsDocument8 pagesProduction Planning & Control: The Management of OperationsMarco Antonio CuetoNo ratings yet

- Trade Confirmation: Pt. Danareksa SekuritasDocument1 pageTrade Confirmation: Pt. Danareksa SekuritashendricNo ratings yet

- EU Regulation On The Approval of L-Category VehiclesDocument15 pagesEU Regulation On The Approval of L-Category Vehicles3r0sNo ratings yet

- International Financial Management 8th Edition Eun Test BankDocument38 pagesInternational Financial Management 8th Edition Eun Test BankPatrickLawsontwygq100% (15)

- GST Rate-: Type of Vehicle GST Rate Compensation Cess Total Tax PayableDocument3 pagesGST Rate-: Type of Vehicle GST Rate Compensation Cess Total Tax PayableAryanNo ratings yet

- Measure of Eco WelfareDocument7 pagesMeasure of Eco WelfareRUDRESH SINGHNo ratings yet

- Quasha, Asperilla, Ancheta, Peña, Valmonte & Marcos For Respondent British AirwaysDocument12 pagesQuasha, Asperilla, Ancheta, Peña, Valmonte & Marcos For Respondent British Airwaysbabyclaire17No ratings yet

- De Mgginimis Benefit in The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesDe Mgginimis Benefit in The PhilippinesSlardarRadralsNo ratings yet

- Belt and Road InitiativeDocument17 pagesBelt and Road Initiativetahi69100% (2)

- Traffic Problem in Chittagong Metropolitan CityDocument2 pagesTraffic Problem in Chittagong Metropolitan CityRahmanNo ratings yet

- Modified Jominy Test For Determining The Critical Cooling Rate For Intercritically Annealed Dual Phase SteelsDocument18 pagesModified Jominy Test For Determining The Critical Cooling Rate For Intercritically Annealed Dual Phase Steelsbmcpitt0% (1)