Understanding Anthropometry in Nutrition

Uploaded by

2begeniusUnderstanding Anthropometry in Nutrition

Uploaded by

2begenius2

Anthropometry

3

Introduction

Anthropometrythe study and technique of human body measurement is the most commonly used method for the assessment of two of the most widespread nutrition problems in the world: (1) protein-energy malnutrition, especially in young children and pregnant women; and (2) obesity, or overweight, in all age-groups (Jelliffe and Jelliffe, 1989). Measurements of weight, height (or length) and, less frequently, subcutaneous fat and muscle, are the usual data collected. This chapter covers the basic indiceslow birth weight, height-for-age, weight-for-height, weight-forage, mid-upper arm circumference, body mass indexderived from anthropometric measurements related to body size and composition, as well as standard cut-offs for indicators, and their application to decisionmaking at individual and population levels. At the individual level, anthropometry is used to assess compromised health or nutrition well being, need for special services, or response to an intervention. A one-time assessment is used during emergency situations to screen for individuals requiring immediate intervention. Under nonemergency conditions, single assessments are used to screen for entry into health or nutrition intervention programs either as an individual or as a marker for a household or community at risk. Trend assessments for individuals, such as periodic monitoring of weight gain in children three years and younger, are used to detect growth problems, to intervene early enough to prevent growth failure, or to assess an individuals response to some type of intervention. At the population level, anthropometric data from a single assessment provide a snapshot of current nutrition status within a community, and should help to identify groups at risk of poor functional outcomes in terms of morbidity and mortality (Gorstein, et al., 1994). Under emergency conditions, these static measurements are used to identify priority areas for assistance. In non-emergency situations, one-time anthropometric assessments are used for geographic targeting and as the basis for

resource allocation decisions. Repeat survey results allow analysis of trends, with anthropometric data possibly serving as concurrent indicators of impending food shortages in the context of an early warning system, as indication of service delivery problems or successes, and as an indicator of population-based response to interventions.

Advantages

Anthropometric measurements are: (1) non-invasive and relatively economical to obtain; (2) objective; and (3) comprehensible to communities at large. They produce data that can be graded numerically, used to compile international reference standards, and compared across populations. They can also supply information on malnutrition to families and health care workers prior to the onset of severe growth failure (or excessive weight gain).

Disadvantages

The disadvantages of anthropometry lie in: (1) the significant potential for measurement inaccuracies; (2) the need for precise age data in young children for construction of most indices; (3) limited diagnostic relevance; and (4) debate over selection of appropriate reference data and cut-off points to determine conditions of abnormality (adapted from Jelliffe and Jelliffe, 1989).

Selecting indicators and cut-off points

Task managers are frequently faced with decisions about which anthropometric data should be collected and which indices constructed for a particular purpose. They can be used as a proxy for household poverty, to describe the overall picture of nutrition in a region or country, to determine target areas for delivery of nutrition/health interventions, to monitor project progress or to evaluate project impact (see Box 2-1). While every context warrants individual consideration of the range of anthropometric indicators and an evaluation of logistical constraints and the specific

objectives of the exercise, some indicators are used frequently. For example, 2Z weight-for-age is the most common index of childhood malnutrition for children under 3 years. (See Annex A for a related discussion of indicator sensitivity and specificity and for an explanation of Z scores.) It is important to note that each index delivers unique informationin children, weight-for-height does not substitute for height-for-age or weight-for-age, as each reflects a particular combination of biological processes. Guidance on the range of uses for each indicator and target group is included in the text beginning on page 13. Refer to Annex A for summary recommendations on survey design issues for various policymaking and program management purposes.

Box 2-1: Potential Objectives for Use of Anthropometric Indicators

Identification of individuals or populations at riskindicators must reflect past or present risk, or predict future risk. Selection of individuals or populations for an intervention indicators need to predict the benefit to be derived from the intervention. Evaluation of the effects of changing nutritional, health, or socioeconomic influences, including interventionsindicators need to reflect response to past and present interventions. Excluding individuals from high-risk treatments, from employment, or from certain benefitsindicators predict a lack of risk.

(WHO Expert Committee, 1995)

Measurement issues

Weight (in grams or kilograms) Various types of scales are available to measure the weight of a child, including spring scales (Salter) or beam balance scales. Hanging scales are commonly used in many countries because they can be transported easily, can be used in almost any setting (particularly where a flat surface is not available) and are relatively inexpensive. Direct recording scales have been developed by Teaching Aids at Low Cost (TALC)1 where a growth chart is inserted into the scale and a pointer indicates the spot on the chart. A family member can mark the chart, which encourages participation in the growth promotion activity. Balance beam scales are commonly used in health centers, as they need to be positioned on a flat surface for accurate measurement and are not easily transported. Standing beam scales are used to measure weight of adults, particularly in health centers. UNICEFs UNISCALE is a new nonbeam or digital scale that allows for the calculation of both adult and infant weight. An adults weight is measured, then the adult accepts an infant in her/his arms on the scale and the additional weight is automatically calculated. Standing scales (both beam and digital) must be placed on a flat horizontal surface. Weight is usually measured to the nearest 100 grams (see Table 2-1 for available measurement tools).2

1. TALC can be contacted at PO Box 49, St. Albans, Herts, UK, AL14AX. Telephone (44 1) 727 853869, Fax (44 1) 727 846852. Information on low cost educational materials, books, slide sets, and newsletters is available at www.talcuk.org. 2. Weighing scales can be procured through UNICEFs supply services in Copenhagen. Contact the Customer Service Officer at telephone: (45) 35.27.35.27, Fax: (45) 35.26.94.21, email: supply@unicef.dk or customer@unicef.dk, or on the web at www.supply.unicef.dk/. UNICEF-New York telephone: 212-366-7000; fax: 212-887-7465.

Anthropometric Assessment Tools

Height/Length (in centimeters) Height is measured as recumbent length for the first two years of life. After the age of two, a childs stature can be measured in the standing position. Measurement of length requires a Shorr-Board or locally produced length board (specifications for constructing such a board are available from UNICEF, CDC and others and can be constructed easily). To measure height, a fixed, non-stretchable tape measure marked by 0.5 centimeter intervals (to the millimeter is desirable), a carpenters triangle or substitute to ensure the childs head is at a right angle to the wall, a straight wall and an even floor surface are necessary to collect accurate height measurements (see Table 2-1 for available measurement tools). Arm Circumference (in centimeters) Special tape measures (Shakir strip or insertion tape) have been developed to measure arm circumference. A non-stretchable centimeter tape or finger and thumb measurement (for children) can also be used. Measuring tapes will be cut and marked differently depending upon the population (children or women) being measured. With the arm hanging relaxed, the circumference at the midpoint between the shoulder and elbow is measured to the nearest 0.1 cm or the color (e.g., red indicates severe wasting, yellow is moderate, and green signals adequate nutrition status) on the tape noted. See Figures 2-1 and 2-2, for more detailed information on measuring arm circumference. Accuracy of these measurements is influenced by the type and condition of the equipment and the qualifications and training of the individual taking the measurements. The equipment should be routinely calibrated by regularly measuring something of known weight or height. Measurements are recorded in a health card, on a growth chart, or in another reporting system. Detailed instructions for taking weight, height and arm

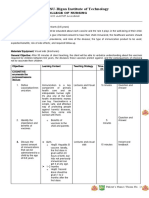

Table 2-1: Comparison of Different Types of Measuring Tools

Use

UNICEF , and TALC : Subject to observer Tapes as well as error, may pull instructions for tape too tight making and using these available

a b

Measuring Tool

Convenient, but not of much use in measuring arm circumference in children under the age of one. Exact age of child is required to interpret results. Sturdy, easy readability, can be tared, but heavy and not easily portable Is easy to use, but slow. Durable, good readability, but may not be very portable. Accurate and can be standardized Sturdy, durable, and also portable. Can be difficult to read with a swinging needle. Accurate and standardized Very easy to use. Can be tared to mothers weight to measure weight of infants. Sturdy, durable and portable. Scale needs

Source

Accuracy/ Standardization

Advantages and Disadvantages

Cost

UNICEF: Pack of 50 for $ 4.25. TALC: $ 0.25 0.40 each

Mid-Arm Circumference Tape (MUAC)

Measures the circumference of the upper arm to assess current nutritional status

Single Beam clinic scales

Used to measure weights of children

CMSc Weighing Equipment (UK), UNICEFa UNICEFa, local manufacturers

Accurate and can be standardized

CMS: $150300 UNICEF: $85.52 $1525

Single Beam free hanging scales

Used to measure weight of children

Accurate and can be standardized

Dial Spring Scales

Used to measure weights of very young children and older children UNICEFa

CMS (UK)c

$3560

Electronic Scale (UNIscale)

Measures weight of children and adults

$90

to be replaced when batteries are exhausted (10 year life span) TALCb Very accurate and easily standardizable Sturdy, and highly durable, easy to understand (even by nonliterate populations). Are sturdy and durable, with good readability. Accurate measuring may require two people Needs two people for for accurate measuring. Subject to tearing. Good readability and portability Needs to be mounted on the wall, not portable, but easy to use. Measures height up to 2 m $25

TALC Direct Recording Scale

Measures growth of children by directly recording weight on a childs growth chart Can be locally Should be accurate manufactured (inand easy to structions available standardize from CDCd and TALC)b, and UNICEFa TALCb, and UNICEFa Accuracy depends on the accuracy of height and weight measures taken from other sources (Scale, board) Accurate, and standardizable

Length/height boards

Used to measure recumbent length in children under the age of 2, and standing height of older children

Price varies between locally manufactured or purchased, $10285 UNICEF: $350 TALC: $27.50, UNICEF: NA

Weight/height Chart (Thinness Measure)

Used to distinguish between stunting and acute malnutrition. Color-coded to identify nutritional status UNICEFa

Height Measuring Instrument

Measures height of children and adults

$NA

a. UNICEF Supply Division, UNICEF Plads, Freeport; DK-2100, Copenhagen, Denmark. Tel: (45) 35-27-35-27; fax (45) 35-26-94-21; e-mail: supply@unicef.org; website: www.supply.unicef.dk; or contact UNICEF field office: www.unicef.org/uwwide/fo.htm. b. Teaching Aids at Low Cost (TALC), PO Box 49, St Albans, Herts AL14AX, England; Tel: (44) 01727-853869; fax: (44) 01727-846852; website: www.talcuk.org. Payments from overseas must be made by 1) International money order, National Giro or UK postal order; 2) Sterling cheque drawn on UK bank; 3) Eurocheque made out in Sterling; 4) US dollar check drawn on US bank using correct rate of exchange; or 5) UNESCO coupons. c. CMS (UK) Weighing Equipment Ltd., 18 Camden High Street, London NWI OJH, U.K.; Tel: (44) 01 387-2060 or (44) 020 7383-7030. d. Center for Health Promotion and Education of the Centers fo Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Rd., NE, Atlanta, GA 30333; website: www.cdc.gov. (Adapted from Griffiths, 1985)

10

Figure 2-1: Measuring Arm Circumference with a Tape Measure

Source: Savage-King & Burgess, 1993.

circumference measures are provided in several other resource manuals: UNICEF: Growth Monitoring, 1986; FAO Supplementary Feeding Programs, 1990; and I. Shorr, How to Weigh and Measure Children, 1986 and in Annex 2 of the WHO Expert Committee Report (1995) Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry. Age (in months) Age is often the most difficult measurement to obtain. The first step is to examine reliable birth records if available for the child. If this source is not available, it will be necessary to estimate birth date and age. It is important to know the traditional calendar if age is to be imputed from talking with the mother. An example of a local calendar is provided in Figure 2-3. Using the triangulation method (asking information in several

11

Figure 2-2: Measuring Arm Circumference with a Shakir Strip

Midpoint between tip of shoulder and elbow

Straight arm

Source: Savage-King & Burgess, 1993.

different ways) to confirm the birth date/age of the child will improve the accuracy of the measurement. For example, after estimating the age of a child with a local calendar compare dental eruption, height, and motor development with a separately assessed child of similar age (Jelliffe and Jelliffe, 1989).

International references

The current international reference, adopted by the World Health Organization, uses data from the US National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS)

12

Figure 2-3: Seasonal Calendar of a Community in The Philippines

(FAO, 1993b)

13

as a benchmark of growth in infants and children. The NCHS compiled the weights and heights of thousands of healthy children with reference data derived from several sources. Information on infants from birth to 36 months of age was collected between 196075 using a population of middle-class, white, bottle-fed Americans. Data for children ages 218 years are from the Health Examinations Survey and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), and are representative of all socioeconomic, ethnic, and geographical groups. There is continuing debate about the appropriateness of these references for children in developing countries. The NCHS reference is composed of several different sample populations and as a result, the curves are disjointed at 24 months. The majority of the study population was bottle/formula fed, reflecting inadequately, the growth patterns of breastfed infants.3 In addition, measurements were taken at three rather

3. In 1995, the WHO Working Group on Infant Growth concluded that to adequately reflect growth patterns consistent with WHO feeding recommendations (i.e., exclusive breastfeeding through 6 months, with continued breastfeeding combined with adequate complementary foods through two years), new growth curves based on reference data from exclusively breastfed infants from a variety of countries/regions should be developed. A consistent, distinct pattern of growth for infants breastfed for at least 12 months emerged from an analysis of multiple, geographically diverse growth studies by the Working Group. Typically, breastfed infants grew as or more rapidly than the NCHS-WHO reference for 2 to 3 months, but showed a relative deceleration, particularly in weight, from 3 to 12 months. Mean head circumference on the other hand, was above the NCHS-WHO median throughout the first year. In the studies that went through the second year, there was a reversal of the trend, with weight-for-age, lengthfor-age, and weight-for-length returning toward the current NCHS-WHO reference means between 12 and 24 months of age. In the absence of a revision of the current reference growth curves, health workers can easily misdiagnose thriving breastfed babies as growth faltering, and wrongly counsel mothers to introduce solids and breastmilk substitutes unnecessarily early on. In many environments, the risk of morbidity and mortality due to contaminated feeding utensils and foods is high (Dewey, et al., 1995 and WHO Working Group on Infant Growth, 1995). The new growth curves are anticipated in late 2004 or early 2005.

14

than one month intervals, which is less than ideal for characterizing the shape of the growth curve. However, various studies have shown that the growth standards achieved by children under 5 years of age in the NCHS reference population can be attained by children in developing countries if they are given adequate food and a relatively clean environment. Therefore, WHO has endorsed these as a universal reference. The development of country-specific references is time consuming and costly, and use of a global reference has the advantage of permitting cross-country comparisons.

Low Birth Weight (LBW)

Inadequate fetal growth (often approximated by low birth weight) is a proxy indicator of poor maternal nutritional status as well, as a predictor of risk for neonatal, infant, and young child (through at least 4 years) morbidity and mortality. There is some evidence that over the long term, growth-retarded infants may experience permanent deficits in growth and cognitive development. Determinants of LBW include inadequate maternal protein-energy consumption, anemia, malaria, tuberculosis, and smoking. The newborns weight (in grams) is generally taken immediately after delivery or within the first 24 hours of life. Although weight at birth by gestational age is the best measurement (to differentiate between infants who are small because they are pre-term and full-term infants who are underweight), gestational age is difficult and often impossible to assess or obtain in developing country settings. Thus under most circumstances, incidence of low birth weight (defined as birth weight < 2500 gms) is assessed and used as a proxy for small for gestational age (SGA). Table 2-2 provides a summary of currently established cut-offs for LBW in individual newborns and for signaling when LBW is a problem of public health significance. At the individual level, in order to reduce morbidity and mortality and optimize long-term growth and performance, LBW can be used for

15

Table 2-2: Recommended Cut-offs for Low Birth Weight

Indicator Low Birth Weight (LBW) Small for Gestational Age (SGA) Chest Circumferencec

a

Individual Newborn Birth weight < 2500gms 10th percentile < 29 cm

Estimate of Population Risk Prevalence > 15%

b

Prevalence > 20% Prevalence > 15%

a. The 1990 World Summit for Children set as an end-of-century goal the reduction in the incidence of low birth weight to less than 10 percent. However in 2003, incidence was 14 percent (UNICEF). b. Populations with LBW prevalence of >15% (approximately twice the level of high income settings) are at risk of long-term adverse effects on childhood growth and performance. c. Not yet established as an official indicator of fetal growth. (WHO Expert Committee, 1995)

screening, diagnosis, risk referral, and surveillance purposes (WHO Working Group on Infant Growth, 1995). At the population level, LBW information is used to generate population estimates of the public health significance of the problem, for targeting of interventions, to stimulate public health action, and to monitor and evaluate health and development progress. See Table 2-3 for global LBW prevalence rates. Keep in mind that LBW data are prone to bias for several reasons. Birth weights are generally collected in hospitals and clinics, introducing the possibility of bias in areas with poor health care coverage and where the majority of non-emergency births occur at home.

Weight-for-age (W/A)

Weight is influenced both by height and thinness. Low W/A (underweight) is a combination indicator of height-for-age (H/A) and weight-for-height (W/H). W/A is the most commonly reported anthropometric index and used frequently for monitoring growth, identifying children at risk of growth failure, and assessing the impact of intervention actions in growth promotion programs. It is as sensitive an indicator as H/A in children

16

Table 2-3: Percentage Prevalence Babies Born with Low Birth Weight (< 2500 grams)

Region/ Country Percent Prevalence LBW

12 10 19 14 11 13 25 12 17 21 15 11 12 22 11 14 14 16 23 42 13 14 16 17 12 9 18 31 9 13 15 7 12 10 11

Region/ Country

Percent Prevalence LBW

Region/ Country

SOUTH ASIA Bangladesh India Maldives Pakistan Sri Lanka

Percent Prevalence LBW

30 30 22 19 22

AFRICA Angola Botswana Burkina Faso C.A.R. Cameroon Cape Verde Comoros Congo, Dem. Rep. Cte dIvoire Eritrea Ethiopia Ghana Guinea Guinea-Bissau Kenya Lesotho Madagascar Malawi Mali Mauritania Mauritius Mozambique Namibia Niger Nigeria Rwanda Senegal Sudan Swaziland Tanzania Togo Tunisia Uganda Zambia Zimbabwe

E.EUROPE and CENTRAL ASIA Albania Armenia Azerbaijan Belgium Bulgaria Croatia Czech Republic Hungary Kazakhastan Kyrgyztan Romania Russian Federation Turkey Turkmenistan LATIN AMERICA and CARRIBEAN Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Barbados Belize Bolivia Brazil Chile Columbia Costa Rica Cuba Dominica Dominican Rep. Ecuador El Salvador Guatemala Guyana Haiti Honduras Jamaica Mexico Nicaragua Panama Paraguay Peru Suriname Trinidad/Tobago Uruguay Venezuela

3 7 11 8 10 6 7 9 8 7 9 6 16 6

8 7 10 6 9 10 5 9 7 6 10 14 16 13 13 12 21 14 9 9 13 10 9 11 13 23 8 7

MIDDLE EAST and NORTH AFRICA Algeria Bahrain Egypt Iran Iraq Jordan Lebanon Morocco Oman Saudi Arabia Tunisia Yemen EAST ASIA China Fiji Indonesia Korea, Rep. of Malaysia Mongolia Myanmar Papua New Guinea Philippines Solomon Is. Thailand Vietnam TOTALS Sub-Saharan Africa Middle East and North Africa South Asia Latin America and the Caribbean East Asia and the Pacific World Least Developed

7 8 12 7 15 10 6 11 8 11 7 32 6 10 10 4 10 8 15 11 20 13 9 9 14 15 30 10 8 16 18

(UNICEF, 2004)

17

under three years, and it has the advantage of requiring only one relatively simple physical measurement (i.e., weight). However, because it is dependent upon accurate age data availability, rounding of age is the frequent cause of substantial systematic bias (Gorstein, et al, 1994). Different age groups also affect sensitivity of W/A. Among the three most common indices (W/H, H/A, W/A)while none of them have high predictive capacitiesweight-for-age has the highest predictive ability for childhood mortality (Pelletier, 1991). The assessment of early growth deficits in an individual childoften detected during monthly growth monitoring sessionsis equally if not more important than identifying the already malnourished child. W/A (or gainsee Box 2-2), can be used to identify children at better, weight gain risk of becoming malnourished, and guide preventive measures such as

Box 2-2: Rate of Weight Gain

In addition to assessing growth patterns through charting serial W/A measurements, Savage-King and Burgess (1993) suggest the following indicators of inadequate rate of weight gain in children < 24 months: A child who has lost weight 06 month old is gaining less than .5 kg/month 612 month old has no weight gain for 2 months 1224 month old has no weight gain for 3 months, especially if a weight is below the 3rd centile Tool #4 discusses alternative definitions of adequate growth patterns using a combination of minimum monthly weight gain for different ages with other indicators of health and nutrition status.

18

nutrition counseling and entry into short-term food supplementation programs. (See Promoting the Growth of Children: What Works [Tool #4] for a complete discussion of growth promotion.) At the population level, W/A can be used to identify areas of highest need for interventions and to assist in the allocation of resources among communities or regions. Weight-for-age is also used to gauge response to program interventions and to predict the health consequences of anthropometric deficits for populations (based on the predictive relationship between W/A and childhood mortality). The younger the child, the better the use of W/A as an indicator of nutritional status. As described earlier, the international reference standard uses data from the NCHS. To identify underweight, a childs actual weight is compared with that of a reference child of the same sex at exactly the same age. Annex B, Tables B-1ac contain the reference data for children 05 years. See Annex A for a discussion of the presentation of W/A data as Z-scores. Table 2-4 contains the proposed classification of malnutrition in a population using prevalence of low W/A. The classification of severity of malnutrition is useful for targeting purposes, but is not based on functional outcomes. Even low levels of underweight may be a cause for concern

Table 2-4: Classification of Malnutrition by Prevalence of Low Weight-for-Age

Degree of Malnutrition Low Medium High Very high

(WHO Expert Committee, 1995)

Prevalence of Underweight (% of children < 60 months, below 2 Z-scores) < 10 1019 2029 30

19

because only 2.3% of children in a well-nourished population would be expected to have W/A < 2Z scores.

Height-for -age (H/A) is a measure of cumulative linear growth and is Height-for-age often influenced by long-term food shortages, chronic and frequent recurring illnesses, inadequate feeding practices, and poverty. This index is used primarily with children under five years of age, with low H/A commonly not appearing before 3 months of age. Children who are short for their age relative to a reference standard are classified as stunted. The prevalence of stunting among children generally increases with age up to 2436 months and then remains relatively constant thereafter.

For individual children, H/A is not used to monitor growth because of errors in measurement of relatively small changes in the short-term. In regions where there is a known high prevalence of stunting such as South Asia, H/A can be used to screen individual children under two years of age for intervention. In areas with low prevalence of low H/A, short children are more likely to be genetically short, making it inappropriate to assume a pathological basis for low H/A or to use the index as a screening tool. (This can often be ascertained by looking at the height of the childs parents.) At the population level the prevalence of stunting is useful for long-term planning and policy development, for targeting a range of interventions to a community(s), and for monitoring malnutrition at the community, regional, or national level. H/A is frequently used as a reflection of socioeconomic status and equity. For example, height measurements of similar age groups at intervals of years can demonstrate positive or negative secular change within a community, region, or country. Poverty analyses often use stunting as a nutritional indicator since it is cumulative and cannot be compensated by fatness. To identify whether a child is stunted, his/her actual height is compared with that of a reference child of the same sex at exactly the same age.

20

Annex B, Tables B-2ae contain the NCHS reference tables for H/A for children ages 060 months. Stunting data are presented as Z-scores, comparing a child or group of children with a reference population to determine relative status. See Annex A for a full discussion of Z-scores. To assess or estimate the prevalence of malnutrition in a population, results are presented as the prevalence of children who fall below the standard cut-off. Table 2-5 contains the proposed classification of malnutrition in a population using prevalence of stunting. The classification of severity of malnutrition is useful for targeting purposes, but is not based on functional outcomes. Interpret low and medium with cautiononly 2.3% of children in well-nourished populations would be expected to fall below 2Z-scores, making even low levels of stunting cause for concern. All cut-offs are merely indicators of risk, not necessarily of actual malnutrition.

Weight-for -height (W/H) measures body weight relative to height. Beeight-for-height cause weight can fluctuate rapidly in children due to illness or inadequate food intake, W/H reflects the current nutritional status of a child, with low W/H (wasting) indicating current acute malnutrition with failure to gain weight or actual weight loss. However, low W/H can also be a result of a chronic condition in some communities. Weight in individual children

Table 2-5: Classification of Malnutrition by Prevalence of Low Height-for-Age

Degree of Malnutrition Low Medium High Very high

(WHO Expert Committee, 1995)

Prevalence of Stunting (% of children < 60 months, below 2 Z-scores) < 20 2029 3039 40

21

and population groups may exhibit marked seasonal patterns associated with changes in food availability or disease prevalence. In non-emergency situations, the highest prevalence of wasting generally occurs in young children 1224 months of age. Among individual children, W/H is a useful index for assessing nutrition status under famine conditions and for identifying short-term nutrition problems in non-emergency situations. Wasting is the usual indicator of choice for targeting treatment of diarrheal and other diseases. High W/H (> +2 Z-scores) is used to screen children at risk for developing obesity and future related morbidity such as heart disease. Given that a childs weight should be more or less the same for a given height regardless of age, W/H has the advantage of not requiring knowledge of childrens ages (Gibson, 1990). At the population level under non-emergency conditions, W/H is usually relatively constant at less than 5% with the exception of the Indian subcontinent where prevalence rates are substantially higher (e.g., in Bangladesh). W/H is used for determining seasonal stresses and allocating resources to vulnerable areas and population groups. In the case of disasters, the W/H index can help to determine the severity of the emergency, and the need for relief food rations. At the opposite extreme, W/H is used to identify priority areas for interventions to reduce rates of overweight and obesity. As described earlier, the international reference standard uses data from the NCHS. To identify whether a child is wasted or overweight, a childs actual weight is compared with that of a reference child of the same sex at exactly the same height. Annex B, Tables B-3ae contain the NCHS reference tables for weight-for-length and weight-for-height. See Annex A for a discussion of the presentation of W/H data as Z-scores. Table 2-6 contains the proposed classification of malnutrition in a population using prevalence of wasting. As is the case with height-for-age and

22

Table 2-6: Classification of Malnutrition by Prevalence of Low Weight-for-Height

Degree of Malnutrition Low Medium High Very high

(WHO Expert Committee, 1995)

Prevalence of Wasting (% of children < 60 months, below 2 Z-scores) <5 59 1014 15

weight-for-age, the classification of severity of malnutrition is useful for targeting purposes, but is not based on functional outcomes. Because only 2.3% of children in well-nourished populations would be expected to fall below 2Z-scores, even low levels of wasting may be cause for concern. See sections on overweight under Body Mass Index (see page 26) and Adolescent Anthropometry (see page 34) for further discussion of cut-offs and population-based prevalence rates.

Mid-Upper Ar m Cir cumfer ence (MUAC), the measure of the diameter of Arm Circumfer cumference fat, bone, and muscle tissue of the upper arm, is an alternative index to consider in situations where it is difficult to collect weight and height measurements. For example, in settings where health workers are illiterate or under emergency conditions, when screening is more important than counseling, MUAC is useful. MUAC offers the operational advantages of a simple, easily portable measurement device (the arm band/ tape) and the use of a single cut-off for children under five years of age (12.5 or 13.0 cm) as a proxy for low W/H or wasting. MUAC has also been used as a screening device for pregnant women; because MUAC is generally a stable measure throughout pregnancy, it is used as a proxy of prepregnancy weight, and therefore an indicator of risk for low birth weight babies. One type of color-coded measuring tape, the Shakir strip, is made from locally available materials and is appropriate for illiterate/

23

innumerate workers; red signifies severe malnutrition, yellow is moderate malnutrition, and green signals adequate nutrition. (See discussion on p.7 for more information on measuring tools.) Disadvantages of the index are the large variability in MUAC measurements (a 0.5 cm error in MUAC has greater implications than a 0.5 cm error in height) and the increased time/effort necessary for training and standardization of MUAC measurements. Comparisons of MUAC with a fixed cut-off and low W/H derived from the same population have demonstrated poor correlation of the two indicators when used for determining individual nutrition status. More children were identified as malnourished by MUAC (false positives), with the attendant implications for diminished cost-effectiveness of an intervention program. However, at the community level, MUAC has been found to be a superior predictor of mortality risk, and thus could serve as an effective screening tool (WHO Expert Committee, 1995). At the individual level, MUAC-for-age is recommended for screening purposes to identify infants/children and pregnant women who need supplementary food or therapeutic feeding, and possibly treatment for disease. It is not recommended for assessing response to interventions (WHO Expert Committee, 1995). At the population level, MUAC-for-age or MUAC is useful for targeting purposes (WHO Expert Committee, 1995) including determining the severity of a disaster or emergency situation, the need for/type of relief rations, and priorities for allocation of resources. Because of the high correlation between low MUAC and mortality in under-fives, this index is potentially useful for predicting the consequences of malnutrition identified by anthropometric deficits in populations. WHO Expert Committee (1995) proposed that MUAC with a fixed cut-off be used as an additional screening tool in non-emergency situations (but not as a substitute for weight- and height-based indices), and suggests

24

that MUAC-for-age is an acceptable substitute for W/H in the context of population-level nutritional surveillance. The reference data for MUACfor-age are based on US children aged 6 to 60 months from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES). Annex B, Tables B-4ac contain reference tables for MUAC measurements (median and standard deviations) for boys and girls ages 660 months. Table 2-7 contains the cut-offs and classifications recommended for MUAC in children ages 1 to 5 years. Cut-offs for pregnant women are determined on the basis of local reference data; measurements between 2123.5 cm have been used in the past to determine risk of LBW infants.

Height-for-Age in School Children

Used solely for population-level analysis, this index captures the earlier health and nutrition histories as well as the broader socioeconomic and environmental factors affecting school-age children four to six years after the fact. A height census is the measurement of height of all entering first graders at schools throughout a country. Experience in Latin America (PAHO/WHO/UNICEF, 1997) suggests that the results from a height-forage census can be used to advocate for allocation of social programs, to identify particularly needy geographic areas, and to plan and target poverty alleviation and other types of social welfare programs. Height-for-age

Table 2-7: Classification of MUAC in Children 1260 Months

Classification Normal Moderate wasting Severe wasting

(FAO, 1993a)

Cut-Off Value > 13.5 cm 12.513.5 cm < 12.5 cm

25

in school children is not the most appropriate indicator to target individual or population level nutrition intervention strategies, but rather to advocate for increased resources to the education sector. It is useful for targeting school-based interventions designed to increase enrollment, promote attendance, and prevent dropouts (PAHO/WHO/UNICEF, 1997). As with most anthropometric indicators, it is important to use the school height census findings as part of a more complete set of data about the physical, economic, and sociocultural context of a community or region. Height-for-age data will not answer questions about the determinants of earlier poor health and nutrition conditions. The primary objective of height censuses is the construction of a classification scale and not exact prevalence estimates of height retardation in a specific population (PAHO/WHO/UNICEF, 1997). A school census provides relatively easy access to a population, and may well furnish greater coverageparticularly at first gradethan surveying health center clients. It can be implemented in a few months and is relatively cheap. The technology for obtaining the measurements is simple and inexpensive, and teachers can readily be trained to carry out the survey. The first grade of school is often the point at which the greatest numbers of individuals of similar age from different socioeconomic backgrounds in the country are brought together, allowing for interregional comparisons to be made. It is important that age data are collected rather than making the assumption that all first year students are the same age. And while school-based data may capture high percentages of the school-age population in middle-income countries, the most common source of bias in height-for-age surveys is population coverage. Problems are related either to the exclusion of a large number of schools from the sampling frame because of accessibility issues, or a high percentage of children missing from school enrollments because of gender bias,

26

health status, household poverty and so forth. Typically, the lack of coveragegenerally in economically disadvantaged areasresults in underestimation of stunting prevalence and the distortion of regional classification/prioritization systems. Information on height is usually collected at the level of the individual school. Data are presented as mean Z-scores and estimates of prevalence of low height-for-age, stratified by sex and by age group. Ideally, local school prevalence estimates will be aggregated to correlate with a countrys political or administrative units; the small sample sizes provided by the individual schools have the problem of large standard errors. The Family Assistance Program/Women Head of Household Food Coupon Program (PRAF) in Honduras used an annual nationwide school nutrition census of all 6 to 9 year-old students entering the first grade of public schools to improve targeting of the food coupon distribution system. Recommended references for height-for-age values for school-age children are the NCHS/WHO data in Annex B Tables B-5ab. For a more detailed discussion of the height-for-age census, refer to the joint technical report by PAHO/WHO/UNICEF (1997).

Body Mass Index (BMI)

BMI is defined as: (weight in kilograms)/(height in meters2). For adults in developing countries, anthropometry has largely been used to identify chronic energy deficiency (thinness) and at the opposite extreme, to classify problems of obesity. BMI is highly correlated with fat mass and is therefore a reasonably good index of body energy stores as fat. As an index of nutritional status, BMI accounts for the fact that weight is influenced by height and is therefore less biased by this association than other indices.

27

Chronic energy deficiency According to WHO Expert Committee (1995), at the individual level, onetime measurement of weight or BMI in men and non-pregnant women is of limited use for predicting health risks or benefits from nutrition or health interventions. The degree of unintentional weight loss of an adult is a better predictor of individual morbidity and mortality risk related to low weight or thinness. Nonetheless, the WHO Expert Committee (1995) has published BMI tables (Annex B Table B-6) and established cut-offs for use in determining degrees of chronic energy deficiency in individuals (see Table 2-8 ). With pregnant women, pre-pregnancy or first trimester BMI can be used to screen for food supplementation, and to identify women at risk for delivery of a low birth weight or preterm infant (see page 31 for more information). At the population level, monitoring adult nutritional status with BMI in nonemergency situations can be a useful tool for assessing nutritional or other socioeconomic deprivation. Low BMI data can be used as the basis for targeting services to a community; a changing BMI profile may be indicative of a population undergoing adverse social or economic change.

Table 2-8: Proposed BMI Cut-Offs for Chronic Energy Deficiency in an Individual Adult

BMI Range Chronic Energy Deficiency < 16 1616.9 1718.4 18.524.9

(WHO Expert Committee, 1995)

Diagnosis Grade 3 thinness (severe) Grade 2 thinness (moderate) Grade 1 thinness (mild) Normal

28

Table 2-9: Adult Thinness as a Public Health Problem

Population prevalence BMI < 18.5 59% 1019% 2039% > 40%

(WHO Expert Committee, 1995)

Classification Low prevalence: warning sign, monitoring required Medium prevalence: poor situation High prevalence: serious situation Very high prevalence: critical situation

BMI is also a general indicator of adult health status, particularly low BMI. Establishing a baseline picture of the BMI distribution for a population enables detection of threats to food security and the need for rapid intervention in an area undergoing either man-made or natural disaster emergency conditions. In an emergency feeding program, anthropometric monitoring of adults helps to discriminate between problems of adequate supplementary food supplies and other public health interventions because adults are less susceptible to epidemic infection than malnourished children. Adult BMI data are presumed to more directly reflect dietary adequacy rather than a complicated interplay of infection, appetite, feeding behaviors, and other factors that affect child nutrition status. Table 2-8 contains the recommended cut-offs defining varying degrees of thinness in an individual, and Table 2-9 suggests prevalence levels signifying a public health problem within a population. Overweight Overweight (excess energy stored as fat resulting from energy intake exceeding expenditure) is associated with increased risk of morbidity

29

(e.g., coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus, gallbladder disease, some cancers, and musculoskeletal disorders) in most populations. BMI is used to classify individuals in terms of overweight, with further testing necessary to identify individual risk factors (e.g., smoking, dietary and exercise habits, blood pressure, serum lipids, family history, etc.) for specific types of disease. According to the World Health Report (WHO, 2002), noncommunicable diseases accounted for almost 60% of the worlds 56 million deaths in 2001. Five of the six main risk factors are closely related to diet and physical activity. At the population level, overweight is a sensitive indicator of energy imbalance caused by a combination of excessive energy intake and insufficient energy expenditure. Because it is such a difficult condition to treat, usually begins in childhood, and is already a widespread problem in industrialized countries, interventions need to focus on prevention. Establishing needs and priorities for intervention programs is achieved through representative population surveys, with a prevalence of BMI> 30 (or > 85 percentile) suggested as the principal indicator (WHOTechnical Report Series No. 916, 2003). Age-specific and age-standardized proportions of the population above a certain BMI cut-off can also be used to evaluate health promotion and disease prevention programs in which weight control is one goal. To evaluate interventions for prevention of overweight in populations where prevalence of obesity is low, monitor longitudinal weight development. Efficacy of the intervention can be judged with a case-control study design and a follow-up period of at least five years. Anthropometric data are less useful for targeting specific interventions because of the interplay of genetics with obesity. Genetic differences between populations influence the degree of risk associated with overweight as well as the types of disease that may occur as a result of

30

excess body weight. For example, it appears that abdominal fatness may be less of a risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes in black women than in white, while Asians and Mexican-Americans appeared to have higher risks of developing non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus than Caucasians of similar BMI (WHO Expert Committee, 1995). Table 2-10 contains the recommended cut-offs defining varying degrees of overweight in an individual.

Anthropometry During Pregnancy

Anthropometric evaluation of pregnant women has the advantage of being a fairly widely used, low-technology procedure which generates information about the nutritional status of the mother and growth of the fetus (WHO Expert Committee, 1995). Useful application of anthropometric data from pregnant women depends on the availability of resources and the likelihood of intervening to avert negative pregnancy outcomes. For instance, when limited resources (i.e., no scales) make weight data collection impossible, short height or mid-upper arm circumference may be used as a screening tool. There may be over-classification of at-risk women. Setting cut-offs will similarly depend on availability of local resources for intervention.

Table 2-10: Classification of Overweight in Adults by BMI

BMI Range (kg/m2) 2529.9 3034.9 3539.9 40 and above

(National Institutes of Health, 2004)

Classification Overweight (pre-obese) Class I obese Class II obese Class III obese (extreme obesity)

31

The preferred indicators of pregnancy outcome are pre-pregnancy weight, body mass index (BMI) through the first 20 weeks of gestation, weight gain during pregnancy, or height. These indicators provide some assessment of risk for the woman during delivery and of potential health problems for the newborn child. The WHO Collaborative Study on Maternal Anthropometry and Pregnancy Outcomes (1995) found that anthropometric indicators are more strongly related to fetal growth than to complications of labor and delivery, although stature can be a relatively strong predictor of delivery complications and maternal mortality. For all of these indicators, selection of one or a combination of several will depend upon what is being assessed: maternal and/or infant risk of poor health/nutrition outcomes, selection of one or more interventions, or response to an intervention(s). And critically, the choice of cut-off for a particular indicator rather than the indicator itself, may be the issue of most importance for determining the optimal use of maternal anthropometry. For example, the cut-off for BMI best suited to predict risk for intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) might well be lower than the BMI cut-off that best indicates response to an intervention. The nature of the outcome (e.g., LBW, prematurity), the nature of the intervention (e.g., food or iron supplementation, reduced workload, child-spacing), the distribution of the anthropometric measurement in the population (e.g., percentage of the population below various cut-offs), the prevalence of the outcome, and the importance of the cause targeted for intervention relative to other causes, will influence the selection of indicator and cut-offs. Pre-pregnancy weight Weight prior to pregnancy or within the first 20 weeks of pregnancy is a measurement frequently used to indicate the need for maternal weight gain during pregnancy and to target women for supplementary feeding. It is currently the most useful screening indicator for risk of low birth weight (due to IUGR) in infants. Weight assessment after 20 weeks

32

gestation is used for referring women to facilities where small for gestational age (SGA) and preterm infants can receive specialized care. Population-specific cut-offs for pre-pregnancy weight should be established within the range of 4053 kg. Body Mass Index (BMI) The WHO Expert Committee recommends the use of BMI with pregnant women for prevention of preterm delivery or referral for neonatal care in populations at risk of preterm delivery. Measured during the first trimester, a population-specific cut-off between 17 and 21 has moderate sensitivity and specificity for predictive purposes. Low BMI (population-specific cut-offs) has also been used to determine which women should receive counseling on diet and/or supplementary feeding. It is important to note that there are several assumptions concerning causality of low BMI and the efficacy of the feeding intervention implicit in this choice of targeting indicator: 1) Low maternal BMI is caused by chronically low energy intake and not by morbidity; 2) Low intake is caused by inadequate access to food at the household level, and not by detrimental intrahousehold allocation patterns; and 3) Supplementary food will be preferentially available to pregnant and/or lactating women and will not substitute for the home diet (WHO Expert Committee, 1995). Height/Stature Height in adults is a combination of genetic potential for growth and environmental effects that influence growth. Specifically for pregnancy, it is an estimate of pelvis size and the only anthropometric measure that

33

serves (with moderate accuracy) as a predictor of need for an assisted delivery. In several studies short maternal height has been associated with poor growth of the fetus (intrauterine growth retardation or IUGR) and subsequently, low birth weight. Current recommendations suggest setting population-specific cut-offs between 140150 cm; height less than 145 cm is a cut-off associated with increased risk of maternal mortality (Krasovec and Anderson, 1991). Height should not be used to target a narrow intervention such as supplementary feeding because it does not reflect current nutrition status, nor will it capture maternal response to feeding in most cases. Height is probably best employed as a screening instrument in situations of limited resources, bearing in mind that considerable misclassification of cases will result. Weight gain during pregnancy Although this indicator is most reflective of the pregnancy period (generally 20+ weeks), its findings come at a point when intervention options for the mother or fetus are limited. It is useful for referral for specialized labor and delivery and neonatal care, and for selecting individuals for intervention during lactation. Changes during pregnancy are relative to height and to initial nutritional status; therefore some clinicians suggest that the percentage weight gain relative to pre-pregnancy weight be used (setting a 1525 percent increase as desirable) versus an absolute gain of 10 kg over the course of the pregnancy. Another weight gain cut-off used frequently is 1 kg/month over the last two trimesters.

Mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) may also be considered for screening (not monitoring) purposes as a predictor of low birth weight, particularly in cases where program resources limit equipment options and/or women have only one or very few contacts with the healthcare system during their pregnancy. Because MUAC increases only minimally if at all during pregnancy, it is used as a proxy for maternal pre-pregnancy and early pregnancy weight. The disadvantages of MUAC are the possibility for

34

measurement error, the greater impact of that error for misclassification in comparison to other measurements such as weight, and the increased effort necessary for training and standardization of MUAC measurements. Population-specific cut-offs will need to be determined based on local reference data and availability of resources for intervention. MUAC cut-offs between 2123.5 cm have been used for identification of women likely to have LBW infants (Krasovec and Anderson, 1991). Identification of individuals or population groups at risk for poor pregnancy outcomes is only the first step. An assessment of possible determinants (see Box 2-3) will help to understand the cause of poor maternal weight gain and/or problematic fetal growth during pregnancy as well as direct efforts at intervention.

Adolescent Anthropometry (children 1019 years of age)

Use of anthropometry for diagnostic and screening purposes in adolescents is constrained primarily by the difficulty of capturing the subjects.

Box 2-3: Possible Determinants of Poor Growth during Pregnancy

Some of the pertinent issues to look at include: Availability and access to key foods Cultural perceptions of appropriate diet during pregnancy Estimates of physical work/energy expenditure Prevalence and type of maternal infections

(WHO Expert Committee, 1995 )

35

And while it is a critical time for the development of many health and nutrition risks (e.g., obesity, short stature in girls), it is a pointless exercise unless specially-targeted intervention strategies (nutrition, life skills education, family planning, and STDs/AIDS) prevention will be planned and implemented. It is important to disaggregate adolescent anthropometric data by sex because of the differences in size and timing of the growth spurt between the sexes. Due to the transient nature of adolescent growth patterns and wide variability in timing of maturational changes, age intervals for collecting data should be shortened to six months (as opposed to one-year intervals during middle childhood), for the period two years after the growth spurt until adult height is attained. Height-for-age (H/A), body mass index (BMI), and BMI-for-age are the most commonly constructed indices for this population group. Weight-for height (W/H) is no longer useful because the relationship between weight and height changes with age and maturational stage during adolescence. BMI-for-age is recommended as the best indicator during adolescence, incorporating information on age, providing continuity with adult indicators, and applicable to both underweight and overweight conditions. Provisional references for adolescent anthropometry use NCHS data, which include standard deviations and percentiles of height and weight through the adolescent years. While BMI-for-age percentiles are acknowledged to be skewed toward higher values, they are currently recommended as the best option for uniform reporting purposes until other data are compiled. H/A and BMI-for-age percentiles are presented in Annex B, Tables B-7ab. For individuals, stunting (H/A < 2 Z-scores) is used to identify adolescents who could benefit from improved nutrition or treatment of other underlying health problems, with the greatest impact expected for premenarcheal girls and pre- or early pubertal boys. Particularly for girls,

36

stunting is related to poor reproductive outcomes (low birth weight, cephalopelvic disproportion,5 dystocia,6 and increased risk of cesarean section and possible postmenopausal osteoporosis). Menarche in girls and the attainment of an adult voice in boys indicates that peak stature velocity has already occurred, and the effect of nutrition interventions on stunting will be minimal. Thinness (low BMI-for-age) in adolescents is useful for determining need for supplementary feeding, nutrition education, and referral to medical care, with a suggested cut-off of BMI-for-age < 5th percentile. Adolescents with BMI 85 percentile are at risk of overweight. Generally, in populations where there are large numbers of overweight individuals, it is recommended that adolescents with high BMI have additional screening to identify obesity-related risk factors such as high blood pressure, family history of cardiovascular disease or diabetes mellitus. Use of adolescent anthropometry at the population level is similar to that for individuals. It is helpful to determine median ages for maturational indicators (menarche, breast and genitalia development, attainment of adult voice) for a population in order to facilitate cross comparison with other populations after adjusting for maturational age (WHO Expert Committee, 1995). Summary statistics for thinness should be reported for targeting purposes (mean, SD) by age and sex groups, as well as the frequency below the 5th percentile of BMI-for-age. Identifying regions with a high proportion of thin adolescents will help to guide decisions about design of intervention programs and the allocation of resources. Premenarcheal

5. Cephalopelvic disproportion is a condition in which the maternal pelvis is too small for the size of the fetal head. 6. Dystocia denotes a difficult labor due to fetal or maternal causes.

37

girls and pre-pubescent boys are the at-risk groups that will derive the greatest benefit from intervention. To assess response to interventions directed at excess thinness among adolescents, evaluate frequencies of BMI relative to either the NCHS reference data or local reference standards. Secular change in thinness prevalence can be a useful indicator of overall social or economic improvement (or decline). It is recommended that surveillance of adolescents (usually a component of surveillance covering other population groups as well) occur every five years during periods of socioeconomic change or while programs are in progress. During periods of social upheaval or rapid positive (or negative) change, more frequent assessment is optimal. Ten-year intervals are sufficient otherwise (WHO Expert Committee, 1995). Again, report mean and SD of BMI and frequencies of BMIfor-age < 5th percentile. In areas where overweight is an identified problem, prevalence can be estimated by an anthropometric survey. Survey results will also assist with the design or modification of intervention programs. Based on BMI reference data (Annex B Table B-6), report frequencies of adolescents with BMI 85 percentile, mean, median, and SD of BMI and frequency of BMI 30, disaggregated by age and sex. To determine obesity (excessive body fat), the WHO Expert Committee recommends combined use of three indices: BMI-for-age, triceps and sub scapular skinfold thicknesses (TRSKF and SSKF). BMI alone is an inexact measure of total body fat and obesity (implying knowledge of body composition) is limited to those adolescents both at risk of overweight (high BMI) and characterized by high levels of subcutaneous fat (high TRSKF- and SSKF-for-age). The suggested cut-off values in Table 2-11 are provisional, and are based on limited evidence of universal applicability. See Tables B-8a to B-8b and B-9a to B-9b in Annex B for reference percentiles of triceps and sub-scapular skinfold thicknesses for adolescents.

38

Table 2-11: Proposed Cut-Off Values for Adolescent Anthropometry

Indicator Stunting/low H/A Thinness or low BMI for age At risk of overweight Obese (simultaneous use of all three indicators is recommended)

(WHO Expert Committee, 1995)

Indices H/A BMI for age BMI for age BMI for age TRSKF for age SSKF for age

Cut-Off Value < 2 Z-score; 3rd percentile < 5th percentile 85th percentile 85th percentile and 90 percentile and 90th percentile

You might also like

- Understanding Anthropometry in NutritionNo ratings yetUnderstanding Anthropometry in Nutrition36 pages

- Technical Skills of Anthropometric Measurements and Value of Growth Chart - 124057No ratings yetTechnical Skills of Anthropometric Measurements and Value of Growth Chart - 12405728 pages

- Nutritional Assessement Anthropometric Methods100% (1)Nutritional Assessement Anthropometric Methods77 pages

- Comprehensive Guide to Anthropometry AssessmentNo ratings yetComprehensive Guide to Anthropometry Assessment7 pages

- Nutritional Assessment Techniques GuideNo ratings yetNutritional Assessment Techniques Guide71 pages

- Nutritional Assessment Methods ExplainedNo ratings yetNutritional Assessment Methods Explained78 pages

- Understanding Anthropometry in NutritionNo ratings yetUnderstanding Anthropometry in Nutrition84 pages

- Nutritional Assessment Methods ExplainedNo ratings yetNutritional Assessment Methods Explained70 pages

- Understanding Anthropometric MeasurementsNo ratings yetUnderstanding Anthropometric Measurements31 pages

- Understanding Anthropometry MeasurementsNo ratings yetUnderstanding Anthropometry Measurements44 pages

- Anthropometric Indicators Measurement GuideNo ratings yetAnthropometric Indicators Measurement Guide9 pages

- Anthropometric Indicators Measurement GuideNo ratings yetAnthropometric Indicators Measurement Guide92 pages

- Pediatric Anthropometric Measurements GuideNo ratings yetPediatric Anthropometric Measurements Guide65 pages

- Understanding Anthropometry MeasurementsNo ratings yetUnderstanding Anthropometry Measurements44 pages

- Nutritional Assessment For Children and AdolescentsNo ratings yetNutritional Assessment For Children and Adolescents32 pages

- Anthropometric Standards in Nutrition RisksNo ratings yetAnthropometric Standards in Nutrition Risks98 pages

- Anthropometric Indicators Measurement GuideNo ratings yetAnthropometric Indicators Measurement Guide92 pages

- Assessment of Children's Physical GrowthNo ratings yetAssessment of Children's Physical Growth9 pages

- IJMRHS VOl 3 Issue 3 With Cover Page v2No ratings yetIJMRHS VOl 3 Issue 3 With Cover Page v2272 pages

- Anthropometric Standards For The Assessment of Growth and Nutritional Status by Andrés Roberto Frisancho100% (1)Anthropometric Standards For The Assessment of Growth and Nutritional Status by Andrés Roberto Frisancho196 pages

- Nutrition Assessment & Surveillance HandoutNo ratings yetNutrition Assessment & Surveillance Handout71 pages

- 03 FINAL - Module 2 - NiE - Nutrition AssessmentNo ratings yet03 FINAL - Module 2 - NiE - Nutrition Assessment26 pages

- Assessment of Nutritional Status (Group 3)No ratings yetAssessment of Nutritional Status (Group 3)20 pages

- Adhesion of Bacteria and Diatoms To Surfaces in The Sea: A ReviewNo ratings yetAdhesion of Bacteria and Diatoms To Surfaces in The Sea: A Review10 pages

- Nes Et Al Bacteriocin Review 2007 With YoonNo ratings yetNes Et Al Bacteriocin Review 2007 With Yoon16 pages

- Bacteria in The Global Atmosphere - Part 1: Review and Synthesis of Literature Data For Different EcosystemsNo ratings yetBacteria in The Global Atmosphere - Part 1: Review and Synthesis of Literature Data For Different Ecosystems18 pages

- Microbial Production of Biodegradable Polymers and Their Role in Cardiac Stent DevelopmentNo ratings yetMicrobial Production of Biodegradable Polymers and Their Role in Cardiac Stent Development11 pages

- Microbial Production of Biodegradable Polymers and Their Role in Cardiac Stent DevelopmentNo ratings yetMicrobial Production of Biodegradable Polymers and Their Role in Cardiac Stent Development11 pages

- Biosurfactants in Food Industry ApplicationsNo ratings yetBiosurfactants in Food Industry Applications8 pages

- Case Study, Chapter 20, Assessment of Respiratory FunctionNo ratings yetCase Study, Chapter 20, Assessment of Respiratory Function11 pages

- Community-Based Tuberculosis Preventive Treatment Among Children and Adolescent Household Contacts in EthiopiaNo ratings yetCommunity-Based Tuberculosis Preventive Treatment Among Children and Adolescent Household Contacts in Ethiopia15 pages

- 1010224 - 成大急診超音波教學 - Low abdominal pain & Soft tissueNo ratings yet1010224 - 成大急診超音波教學 - Low abdominal pain & Soft tissue123 pages

- CPG Management of Heart Failure (4th Ed) 2019No ratings yetCPG Management of Heart Failure (4th Ed) 2019161 pages

- A Look at The History of The Development of Medical Care in Uzbekistan Before The October RevolutionNo ratings yetA Look at The History of The Development of Medical Care in Uzbekistan Before The October Revolution4 pages

- Drug Induced Liver Toxicity Minjun ChenNo ratings yetDrug Induced Liver Toxicity Minjun Chen500 pages

- Principles of Epidemiology Lecture-3-5 FinalNo ratings yetPrinciples of Epidemiology Lecture-3-5 Final108 pages