Approaches To Syllabus Design

Uploaded by

Edson Tomé VascoApproaches To Syllabus Design

Uploaded by

Edson Tomé Vasco- Approaches to Syllabus Design: Discusses the framework of syllabus design and theoretical perspectives underlying syllabus and curriculum definition.

- Syllabus Content and Definition: Explores the academic content in syllabuses, including theoretical basis and alternatives for designing course content.

- Models for Syllabus Design: Introduces various models used in creating syllabuses, including Tyler's and cyclical models, discussing their theoretical foundations.

- Ideological Approaches to Syllabus Design: Reviews ideological perspectives such as humanist, reconstructionist, and progressivist approaches impacting syllabus design.

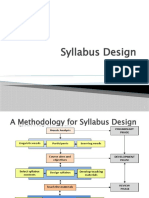

- The Process of Syllabus Design: Details the procedural aspects of designing a syllabus including analysis, objectives formulation, and content selection.

- Evaluation and Opportunities: Examines the methods of assessing syllabus effectiveness and the opportunities for learning improvements.

- Constraints on Syllabus Design: Analyzes the policy and pragmatic constraints affecting syllabus development and the impact on educational practices.

- Conclusion: Summarizes the major themes discussed, advocating for adaptable and learner-centered syllabus design in educational settings.

Common questions

Powered by AINeeds analysis for ESL learners faces several challenges. One primary issue is articulating needs that are often vague or based on immediate desires rather than long-term educational goals . Berwick notes teachers' concerns that not all learners can verbalize their language needs due to social or educational backgrounds . Clark emphasizes the divergent agendas and perceptions of the stakeholders involved, which can skew the needs analysis outcome . To address these, West advocates a balanced approach incorporating both objective data from observations and subjective insights through learner consultation . Additionally, a comprehensive, ongoing analysis process involving frequent evaluations is suggested to capture evolving language needs . These methods allow for accurate assessments despite the inherent complexity of identifying ESL learner requirements accurately.

In curriculum design, particularly for language learning, 'aims' and 'objectives' are distinct yet complementary concepts. Aims are broadly formulated, long-term aspirations that articulate the desired end-products of a course, often expressed philosophically . Van der Walt and Combrink distinguish between overarching 'ultimate aims' and more generalized aims from which specific course objectives derive . Objectives, in contrast, are detailed, specific descriptors of expected learner behavior and achievements by the end of an instructional cycle . Kaufman and English emphasize the importance of formulating measurable, actionable objectives to guide instructional planning . While aims provide a vision or direction for learning, objectives delineate concrete targets to measure progress and success within that framework.

The traditional syllabus design model is characterized by the top-down approach, where the curriculum is designed by policymakers and presented to educators and students, primarily following Tyler and Taba's objectives model . This model is heavily structured around pre-defined goals with little room for negotiation or flexibility. In contrast, modern participatory approaches emphasize consultational and informal decision-making. These approaches advocate involving teachers and learners directly in the syllabus decision-making process, as highlighted by Rodgers, who stresses informal consultational processes, and West, who promotes a triangular decision-making model involving teachers, learners, and communities . While traditional models are objective and administrative, modern approaches focus on collaboration, adaptability, and responsiveness to learner needs.

In syllabus design, 'negotiation' refers to the adaptability and flexibility of educational content and methods to meet the practical needs and theoretical aims of an educational context. White emphasizes that a syllabus must be negotiable and adjustable, reflecting both theoretical tenets and current practices . Theoretical justifications behind a syllabus often prioritize ideal learning outcomes and educational philosophies, whereas practical adaptability requires adjusting to real-world classroom constraints and learner needs . This involves balancing educational ideals with feasible teaching strategies and resources, ensuring both teachers’ and learners’ experiences are valued and including consultational processes where stakeholders influence syllabus adjustments based on emergent needs . Effective negotiation in syllabus design thus bridges the gap between aspirational educational goals and real-world teaching environments, fostering a dynamic and responsive educational framework.

Different authors provide varying definitions of a 'syllabus.' Steyn and Calitz see it as synonymous with 'subject curriculum' . Warwick views it as the academic content of a subject, whereas Nunan describes it as the specification and order of content taught in a language program . Steyn, Badenhorst, and Yule emphasize structuring content for specific subjects to organize yearly work . Van der Walt and Combrink describe it as a statement of learning objectives for a specific period . Herbst views it as outlining ESL teaching policy, aims, objectives, and content . White summarizes that it encompasses work distribution, negotiation adaptability, and administrative guidance . Johnson considers it from a cultural perspective, linked to learning outcomes and opportunities . These definitions reflect the multifaceted nature of syllabi, focusing on structure, objective formulation, content specification, teaching policies, and administrative roles.

Content selection and sequencing are crucial for the effectiveness of ESL programs as they directly influence motivation, engagement, and the development of language skills. Steyn and Dippenaar highlight the need for content that reflects cultural values and relevance, matching the learners' interests and entrance levels . Content should cater to the aims of the course and be applicable both in the short and long term . The sequencing of content, often guided by Bloom’s taxonomy, ensures that learning proceeds from simple recall to complex application and analysis, facilitating deeper cognition and understanding . Inappropriate content or poorly sequenced material can lead to disengagement and poor educational outcomes, undermining program effectiveness and student success in acquiring the language.

The cyclical model of syllabus design comprises steps like situation analysis, aims and objectives formulation, learning content structuring, presenting learning experiences, assessment, and evaluation, repeating these processes to refine outcomes . The spiral model, preferred by Kruger, builds on this by showing the progression and sophistication of learning as students revisit content over time . Malan and du Toit merge these on macro, meso, and micro levels, continuously recycling content at increasing levels of complexity . These models are significant in language learning as they allow for content to be revisited and deepened over time, facilitating better mastery and progression in language competencies. The spiral model ensures continuous development in fluency and understanding, critical for language acquisition.

Ideological approaches significantly influence language syllabus design. Skilbeck identifies three primary educational ideologies: classical humanist, reconstructionist, and progressivist, each with distinct impacts on syllabus design . The classical humanist approach emphasizes the transmission of established knowledge, often creating syllabuses centered on a set body of culturally valued knowledge . The reconstructionist approach aligns with adaptability and relevance, driving design to align academic content with societal needs and changes . Progressivist approaches focus on learner-centered and experience-based learning, promoting flexible, needs-based content selection that supports developmental learning and immediate applicability . Each ideology's influence dictates whether a syllabus will focus more on content mastery, societal relevance, or learner experience, impacting how materials are chosen and how educational goals are prioritized.

The 'communicative needs processor,' as proposed by Munby, aims to create comprehensive profiles of learners' communicative needs, influencing ESL syllabus development by focusing on target situation analysis . However, West identifies critical limitations of this approach: it neglects the methodological components and lacks adequate representation of teachers and learners, rendering it less practical for direct classroom application . The processor's heavy focus on predefined targets may overlook evolving and context-specific learner needs, potentially missing the nuanced adaptability necessary for dynamic language instruction . The model's emphasis on end-goals rather than the learning process presents challenges in real-time curriculum adaptation and responsiveness to learners' immediate educational environments.

Aligning ESL content selection with cultural values can offer several benefits and pitfalls. On the positive side, Cunningsworth suggests that culturally meaningful content can enhance learner motivation and engagement, fostering a sense of ownership and enthusiasm . Dippenaar argues that integrating content reflecting cultural values and ideals facilitates relevant and significant learning experiences, aiding in cultural literacy . However, Bassett notes potential pitfalls, where culturally prescriptive content may lead to fossilization, limiting exposure to diverse perspectives and contemporary relevance . Cox warns against content nostalgically tied to past eras, which may disengage modern learners . The challenge is to balance cultural reflection with inclusivity and forward-thinking content, ensuring educational material remains dynamic and applicable to diverse learner contexts.