0% found this document useful (0 votes)

403 views4 pagesVap Care Bundle Final

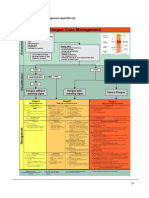

The document outlines a ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) care bundle developed by the West Yorkshire Critical Care Operational Delivery Network. It defines VAP and notes its occurrence in 10-20% of ICU patients is associated with increased mortality and costs. The bundle includes eight evidence-based elements aimed at reducing VAP incidence: 1) use of subglottic suction tubes for patients intubated over 72 hours, 2) maintaining endotracheal cuff pressure between 20-30 cmH2O, 3) daily sedation holds or targeted sedation, 4) semi-recumbent positioning, 5) avoiding unnecessary ventilator circuit changes, 6) judicious stress ulcer prophylaxis,

Uploaded by

Mother of Mercy Hospital -Tacloban Inc.Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

403 views4 pagesVap Care Bundle Final

The document outlines a ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) care bundle developed by the West Yorkshire Critical Care Operational Delivery Network. It defines VAP and notes its occurrence in 10-20% of ICU patients is associated with increased mortality and costs. The bundle includes eight evidence-based elements aimed at reducing VAP incidence: 1) use of subglottic suction tubes for patients intubated over 72 hours, 2) maintaining endotracheal cuff pressure between 20-30 cmH2O, 3) daily sedation holds or targeted sedation, 4) semi-recumbent positioning, 5) avoiding unnecessary ventilator circuit changes, 6) judicious stress ulcer prophylaxis,

Uploaded by

Mother of Mercy Hospital -Tacloban Inc.Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd