0% found this document useful (0 votes)

40 views38 pagesPressure and Diffusion

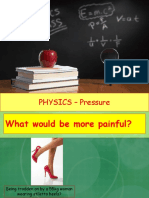

This chapter covers the concepts of pressure and diffusion, explaining how pressure is defined as force divided by area and how it relates to the arrangement of particles in gases and liquids. It includes practical examples such as the effects of pressure on different surfaces, the role of hydraulic systems, and the behavior of particles under pressure. Additionally, it discusses thought experiments and real experiments to explore the relationship between pressure and depth in liquids.

Uploaded by

hajbastarCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

40 views38 pagesPressure and Diffusion

This chapter covers the concepts of pressure and diffusion, explaining how pressure is defined as force divided by area and how it relates to the arrangement of particles in gases and liquids. It includes practical examples such as the effects of pressure on different surfaces, the role of hydraulic systems, and the behavior of particles under pressure. Additionally, it discusses thought experiments and real experiments to explore the relationship between pressure and depth in liquids.

Uploaded by

hajbastarCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd