0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views6 pagesChapter 27 Mohanraj 2015

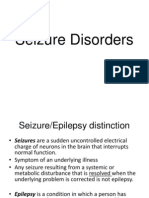

Refractory epilepsy affects 20-30% of epilepsy patients, defined by failure to achieve seizure freedom with two appropriate antiepileptic drug regimens. Management involves reviewing diagnosis, AEDs, considering non-pharmacological treatments, addressing co-morbidities, and optimizing quality of life. The chapter emphasizes the multifaceted nature of refractory epilepsy, highlighting the importance of a comprehensive approach that includes psychological and societal aspects.

Uploaded by

Ponni panteCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views6 pagesChapter 27 Mohanraj 2015

Refractory epilepsy affects 20-30% of epilepsy patients, defined by failure to achieve seizure freedom with two appropriate antiepileptic drug regimens. Management involves reviewing diagnosis, AEDs, considering non-pharmacological treatments, addressing co-morbidities, and optimizing quality of life. The chapter emphasizes the multifaceted nature of refractory epilepsy, highlighting the importance of a comprehensive approach that includes psychological and societal aspects.

Uploaded by

Ponni panteCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd