0% found this document useful (0 votes)

56 views6 pagesUsing The Local Environment

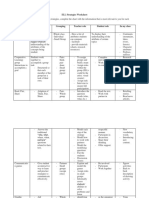

The document discusses the importance of using the local environment for language learning, highlighting activities such as learning walks and community mapping to enhance students' engagement and understanding of their surroundings. It emphasizes adapting these activities to the specific characteristics of the local area and ensuring student safety during outdoor learning. The author provides practical examples and reflections for educators to implement these strategies effectively.

Uploaded by

steelldaynaCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

56 views6 pagesUsing The Local Environment

The document discusses the importance of using the local environment for language learning, highlighting activities such as learning walks and community mapping to enhance students' engagement and understanding of their surroundings. It emphasizes adapting these activities to the specific characteristics of the local area and ensuring student safety during outdoor learning. The author provides practical examples and reflections for educators to implement these strategies effectively.

Uploaded by

steelldaynaCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd