0% found this document useful (0 votes)

496 views6 pagesCommon Intention Under BNS

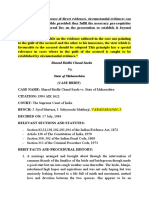

Section 3(5) of the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 establishes a rule of joint liability for criminal acts committed with a common intention, replacing Section 34 of the Indian Penal Code. It outlines essential elements such as prior meeting of minds, shared mental intent, active participation, and a causative link between the intention and the act. The provision emphasizes that mere presence or passive involvement is insufficient for liability, requiring rigorous proof of collective action and intent.

Uploaded by

abhinav.rao1510Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

496 views6 pagesCommon Intention Under BNS

Section 3(5) of the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 establishes a rule of joint liability for criminal acts committed with a common intention, replacing Section 34 of the Indian Penal Code. It outlines essential elements such as prior meeting of minds, shared mental intent, active participation, and a causative link between the intention and the act. The provision emphasizes that mere presence or passive involvement is insufficient for liability, requiring rigorous proof of collective action and intent.

Uploaded by

abhinav.rao1510Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd