READING PASSAGE 1

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1–13, which are based on Reading Passage 1

below.

Sleeping on the Job

Can curling up under your desk, or in a purpose-built sleep pod, for a 10-minute sleep improve your

performance at work?

There are times, typically in the afternoon, when many office workers experience a feeling of

tiredness and may even drift off to sleep in front of their computers. Many workplaces consider

artificial stimulation, provided by coffee or a chocolate bar, more acceptable than a short sleep when

attempting to combat this daytime sleepiness. However, there is considerable evidence that trying

to work during a spell of daytime drowsiness can be costly. “Workplace accidents and errors peak at

the same time that our circadian rhythms (sleep–wake cycle) cause a drop in alertness,” says Dr.

Gerard Kennedy, a sleep specialist based in Melbourne, Australia. “That’s between about two and

five pm,” he says. These biologically based downturns in alertness are natural and occur even if

you’ve had a good night’s sleep. Most workers simply continue during the after-lunch decline or

reach for the nearest energiser: a strong coffee, a can of high caffeine soft drink, a cigarette or some

secretly stored chocolate in the top drawer.

However, a growing number of workers are taking very short sleeps, or “power naps” instead.

“Research shows that a nap can improve your mood and productivity, alleviate tiredness, increase

alertness and reduce errors at work,” says Kennedy. “A nap as brief as 10 minutes will produce

these results.” It seems that the length of the nap is significant. Professor Leon Lack, from the School

of Psychology at Adelaide’s Flinders University, has compared 5-, 10-, 20- and 30-minute naps; he

measured sleepiness, reaction time and cognitive performance before and immediately after a nap

and again during the next three hours. “The 5-minute nap delivered very few benefits,” says Lack.

“The 20- and 30-minute naps produced improvements but the subjects took at least half an hour to

wake up completely.” Lack explains that the longer the sleep, the deeper it is, which can lead to a

feeling called sleep inertia. “The 10-minute nap delivered immediate benefits that lasted for two to

three hours, including a small but significant increase in alertness.”

But how can just 10 minutes of sleep be ensured, when not in lab conditions? Most people take 5 to

10 minutes to fall asleep so they need to lie down for a total of 20 minutes to allow for 10 to 15

minutes of sleep. First, we need to change our attitudes to rest. Australians work an average of 1811

hours each year, according to 2005 figures from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD). This is the fifth highest figure from 20 nations surveyed. In addition, Dr.

Kennedy stated that 9% of 20- to 30-year-olds and 16% of 30- to 50-year-olds are reporting sleeping

problems. But in Australia, a culture where doing anything at all is considered better than doing

nothing, lying down for a while—in the face of deadlines and urgent requests—is regarded as

unacceptable by most companies. Some companies, however, are listening to experts who advise on

ways to help employees take quick naps.

Both low- and high-tech napping methods are available for those who want to try. Low-tech napping

can include the use of a basic relaxation room, or, in the case of the strategic public relations firm

Wordplay, a ‘CushoBed’. This combination of a very large cushion and a couch provides Wordplay’s

staff with a comfortable place to curl up for a short sleep. Then there's the high-tech

‘TechnoSnooze,’ an up-market sleeping pod that arrived in Australia from New York earlier this year,

and which has been leased out to several companies on trial, including advertising agencies State

Right Australia and Instant Publicity. Looking like a space-age reclining armchair, the TechnoSnooze

has a rounded hood that lowers over the head and headphones that play relaxation music. The pod

inclines forward to allow for easy entry, then reclines so that the user’s feet are slightly elevated.

This promotes blood circulation and reduces pressure on the lower back. After 20 minutes, the pod

vibrates gently to wake you.

Harry Baker, the managing director of another large company, doesn’t need such a high-tech

approach. He makes good use of his media company’s meditation room, which includes quiet music,

candles, and incense. He encourages his staff to use it too. “Napping is a good idea,” says Baker.

“It’s like a traffic signal that slows down your brain.”

However, employees need strong workplace support from their bosses and co-workers to feel they

have permission for a mini-sleep as a regular part of their working day. “Workplace napping made a

huge amount of sense to me very quickly, and I assumed the idea would sell itself, but that wasn’t

always the case,” says Kevin Hopkins from State Right Australia, which trialled pod-style napping for

a month. “For napping to be beneficial, you need to ensure good briefing of the managers so they

are clear about the positive outcomes and are equipped to endorse, role-model, and support staff,

� since staff will usually take their lead from managers.” He says staff response was positive: 43% of

those who booked themselves in for a pod nap said they felt ‘good’ and 21% ‘excellent’ afterwards.

Questions 1–4

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage

1? In boxes 1–4 on your answer sheet, write

● TRUE

● FALSE if the statement agrees with the information if the statement

contradicts the information

● NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

The majority of mistakes in the workplace happen in the afternoon.

A short nap of five minutes is enough to reduce errors at work.

People who work long hours are more likely to have sleeping problems.

Doing nothing is acceptable in Australian culture.

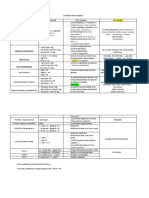

Questions 5–10

Complete the table below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS AND/OR A

NUMBER from the passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 5–10 on

your answer sheet.

Where nap takes place CushoBed TechnoSnooze Used by Wordplay State Right

Australia Instant Publicity 9 _______________ Harry Baker Description Blends features

of a giant 5 _______________ and a sofa. An ultra-modern lounger with a 6

_______________ at the top. Lessens stress on the 7 _______________. Allows you to

sleep for a maximum of 8 _______________. A sweet-smelling room with subtle

lighting and background 10 _______________

Questions 11–13

Answer the questions below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the

passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 11–13 on your answer sheet.

11. To what does Harry Baker compare napping?

12. Apart from their superiors, who do workers need consent from if they are

to feel comfortable taking a nap at work?

13. What do managers need to understand before they can support their staff

in 'sleeping on the job'?

� READING PASSAGE 2

Answer Questions 14–29, which are based on Reading Passage 2 on pages 6 and 7.

Why do singers lose their voices?

A

Singing is a tough business. Every vocal performance involves hundreds of thousands of micro-collisions

of a thin pair of muscular strips called the vocal cords, located in the larynx in the throat. When we are

breathing in, they remain apart; when we sing or speak, air is pushed up out of the lungs, and the edges

of the cords come together in a rapid chopping motion. The air causes the cords to vibrate, creating

sound. The greater the vibration, the higher the pitch, and when a soprano hits the highest notes her

vocal cords are vibrating 1,000 times per second. This transforms a burst of air from her lungs into a

sound powerful enough to shatter glass.

B

Beautiful singing requires flexible cords, but the friction caused by prolonged overuse can erode their

fine, spongy surface and lead to tiny bruises. Eventually, nodules, polyps or cysts form on the vocal

folds, distorting the sound they create. For a singer, the first sign of trouble is often the 'wobble': the

voice fluctuates on and off key because the damaged cords have lost the ability to resonate properly.

Often, there is a 'hole', a point on the musical scale where a singer's vibrating vocal cords fail to produce

the proper tone. The sound produced will be flat, or worse still, barely audible.

C

It was once unheard of for a singer to perform with a faulty voice. However, in recent times, it has

become more common for performances to be interrupted, or even cancelled due to the inability of the

performer to continue. Some opera singers complain of year-round cold symptoms, and steroid

injections and numerous other drugs are often used to get a struggling singer through a performance.

But continuing to sing can cause more damage and create voice-ruining scars, similar to when a football

player continues to play with a damaged knee and eventually needs surgery. There is no precise data on

the number of performers who have undergone surgical procedures, but it is estimated that thousands

have been under the knife. Dusty theatres, stuffy airplane cabins, erratic eating and sleeping patterns

and stress all affect the vocal cords. Add to all this the occupational hazard – at least in opera and

classical music – of taking on roles that require artists to sing beyond their natural range, and a singer's

cords become extremely susceptible to injury.

D

Will Crutchfield, a conductor and vocal coach, laments the fact that this vocal burnout is cutting short

careers and diminishing the power of opera, and he feels that audiences have become accustomed to

hearing voices which are not in peak condition. When he first highlighted the problem, he noticed that it

didn't affect singers until they were in their 30s, but now even singers in their 20s are undergoing

medical procedures to save their careers. These injuries have been linked to a shift in what we consider

quality singing. Across all genres, it has become normal to believe that louder is better, and singers are

pushing their vocal cords like never before. New waves of medical research into dysphonia, or the

inability to properly produce sound, bear this out. In the western world, vocal abuse is surprisingly

common in all professions that rely on the voice, from schoolteachers to opera singers.

E

Steven Zeitels, a specialist vocal cord surgeon, believes that pioneering surgery is the way forward. He

is working on a futuristic solution which will involve implanting a gel made of biomaterial in the tissue of

damaged vocal cords to restore pliability, and therefore the voice. However, some research studies

argue that surgery is not necessarily a lasting fix. According to Lisa Paglin, a singer turned voice coach,

Zeitels has simply found a temporary remedy. ‘Unless a singer makes major changes, “return to

performing” means a return to the vocal abuse that put him/her on the operating table in the first

place’. Her coaching partner Marianna Brilla agrees. ‘You cannot solve the problem by simply relieving

the symptom.’ One observation Paglin and Brilla have made from working with older, classically trained

singers is the way that they use the natural up-down release of the diaphragm to produce sound, rather

than relying on their vocal cords. For Brilla, this represents a real discovery: the root of the problem

today is in classrooms. She believes that students are graduating from music academies without having

learned this natural singing method. In her opinion, today’s students ‘don’t know how to sing, and it’s

leading to injury’.

F

Is it possible that teaching people to sing differently could cure damaged vocal cords forever? Zeitels is

dismissive of such an approach, and quick to deny that his clients’ vocal problems are caused by bad

�technique. ‘People used to think if you needed an operation it meant you don’t know how to sing. The

people I see – they know how to sing!’ Zeitels believes that medical specialists are becoming

increasingly important to the arts, given that any athletic endeavour will eventually take a toll if done for

long enough. Robert Sataloff, who has performed voice-corrective surgery on several award-winning

performers, also resents the notion that surgery is not a sensible way to keep singers healthy. He

believes that surgery, combined with proper education on the dangers of improper singing technique,

can keep people on stage for longer. He concedes that surgery is not a perfect solution, and it probably

never will be, but it is an option.

Questions 14–19

Reading Passage 2 has six sections, A–F. Which section contains the following information?

Write the correct letter, A–F, in boxes 14–19 on your answer sheet.

14. examples of some of the environmental factors which affect singers

15. a reference to a lack of awareness of a correct singing technique

16. details of the physical processes involved when a person sings

17. a defence of the use of surgery to treat vocal injuries

18. a description of the initial indications of vocal problems

19. a reference to modern perceptions of a good singing performance

Questions 20–24

Complete the sentences below. Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each

answer. Write your answers in boxes 20–24 on your answer sheet.

20. The ______________ of a sound is determined by the rate of vibration of the vocal cords.

21. The delicate surface of the vocal cords can be worn down by ______________ if they are

continually overused. 22. Singers with vocal cord damage are often unable to produce a

sound with the correct ______________ at a certain point on the musical scale. 23. Opera

singers are often given a variety of ______________ to make sure they can complete their

performances. 24. Opera and classical performers are at greater risk of injury if they

perform ______________ which place exceptional demands on their voices.

Questions 25–29

Look at the following statements (Questions 25–29) and the list of people below. Match

each statement with the correct person, A, B, C, or D.

Write the correct letter, A, B, C, or D, in boxes 25–29 on your answer sheet.

NB You may use any letter more than once.

25. Surgery provides performers with only a short-term solution to their

problems.

26. The public are now used to attending performances given by singers with

vocal injuries.

27. People are wrong to suggest that performers who undergo surgical

procedures to repair their voices lack singing ability.

28. Surgery works best when used in conjunction with re-training performers.

29. New and innovative surgical techniques hold the key to repairing damaged

vocal cords.

List of People:

Will Crutchfield

Steven Zeitels

Lisa Paglin

Robert Sataloff

��READING PASSAGE 3

The tuatara – past and future

The New Zealand species of lizard, the tuatara, is firmly embedded in the national psyche: an icon for

today which dates from the age of dinosaurs; an ancient reptile commemorated on the back of the five

cent coin. New Zealanders feel an affinity with the tuatara, and accept that active conservation

management is required to ensure it will be among the legacies left to future generations.

When European explorers reached New Zealand in 1769 they found two large islands, which together

they called the ‘mainland’, and many tiny offshore islands around the coast. The naturalists who came

with the explorers disregarded the tuatara, though it is improbable none were seen. Only several

decades later did a tuatara specimen reach the British Museum, where it was eventually classified as

just another type of lizard.

One of the first scientists who realized that aspects of tuatara anatomy were odd – unchanged for tens

of thousands of years – was Albert Gunther in 1876. Gunther believed the tuatara was one of the most

valuable objects in zoological anatomical collections, and also noted, in passing, the reptile was likely to

become extinct. From today’s perspective, it is striking that Gunther expressed no concern about the

probable demise of the tuatara. He and his contemporaries were products of their age, strongly

influenced by Charles Darwin’s theory, which had only recently been published. Their views were

something like this: ‘Extinction is a natural process. It is sad that species disappear, but that is part of

nature.’

There is a second important aspect of Gunther’s work. He recorded, correctly, that some of the

mammals introduced by Europeans were predators of the tuatara – particularly rats. But what he did not

realise was that New Zealand has two species of rat, both introduced, both with an appetite for tuatara:

the ship’s rat came with European explorers and settlers; but the kiore rat had already been in the

country for hundreds of years, brought by Polynesians from the Pacific Islands. Gunther failed to

recognise the distinction, believing all rats to be a relatively recent introduction.

Little further research was conducted until Ian Crook of the NZ Wildlife Service published his findings in

1973, which can be summarised as follows. Tuatara thrive on offshore islands with no rats. Tuatara

never survived on islands with ship’s rats. On a few islands, small and declining populations of tuatara

occur with the kiore. This should not be seen, however, as evidence that tuatara and kiore can coexist.

Rather, Crook proposed, kiore probably only arrived recently on such islands, and thus the small

populations represent extinctions in progress.

Throughout the 1990s, Richard Holdaway and his colleagues at Victoria University in Wellington

documented the surprising discovery that aloes probably arrived about 1800 years ago, although the

human population of New Zealand is thought to be no older than 800 years. How is this possible?

Presumably, Holdaway argued, the kiore were brought by Polynesian explorers who visited the country

but did not settle. Thereafter, the rats were agents of ecological warfare, exterminating perhaps 1000–

3000 species.

The human inhabitants – the Maori – arrived around 1300. This hypothesis is still being debated, but the

evidence continues to accumulate in its favour. Conservation practice has changed dramatically since

Crook’s findings were published in 1973. Eradication of rats from any given environment was believed to

be virtually impossible until about 1980, but since then has become routine. Enormous conservation

benefits are accruing as newly rat-free offshore islands are providing sanctuaries for the country’s rarest

species. In 1995, for example, Nicola Nelson of the Department of Conservation established 68 tuatara

on Titi Island. Since then, four more populations of tuatara have been established elsewhere under

similar conditions. Today, numbers of tuatara are still a fraction of what they once were, but for the first

time in 1800 years the decline has been reversed.

While the recovery of rare species is itself a good thing, the truly significant outcome of this research is

that it liberates the imagination. If we can remove predatory introduced mammals from islands, why not

from the mainland too? Perhaps the questions we ask should demonstrate even more visionary

ambition. Can non-mammalian pests also be removed from the mainland? Our rivers, for example, are

full of surrogate rats, in the form of introduced species of fish called trout. Some day more people will

understand that trout have replaced a whole native fauna in our waterways, just as rats replaced

tuatara on the mainland. Will such knowledge lead to the creation of mainland ‘aquatic islands’ where

�we can once again establish those species of indigenous fish that used to live in our rivers? Similarly,

can bellbirds and tuis replace birds like starlings and mynahs?

The answers to such questions are uncertain, and opposing sides will doubtless be fiercely debated. But

the role of scientific knowledge in illuminating the past will be crucial. Just as we now no longer tolerate

extinction, in the future we may no longer accept a mainland devoid of the biological wonders of our

past such as tuatara. Conservation is thus not primarily about the past but about imagining and then

creating the future we wish for our children and ourselves. For 80 million years until humans arrived,

tuatara occurred throughout New Zealand – might they do so again?

Questions 27–31

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D. Write the correct letter in boxes 27–31 on your answer

sheet.

27. What are we told about the Europeans who arrived in 1769?

They thought there was only one large island.

They had not come to study natural history.

They had no interest in the tuatara.

They sent a tuatara to the British Museum.

28. What does the aster say about Albert Gunther in paragraph 3?

He believed the tuatara could fetch a high price.

He was typical of his generation of scientists.

He disagreed with Charles Darwin’s theory.

He wanted to stop the tuatara becoming extinct.

29. What did Albert Gunther think about the rats in New Zealand?

They did not eat the tuatara.

There was one species of rat.

There had always been rats in New Zealand.

They were killed by Polynesians.

30. What did Ian Crook conclude from his research?

Tuatara are safe on small islands.

Ship’s rats kill more tuatara than kiore.

Kiore cannot swim to offshore islands.

Rats and tuatara cannot live together.

31. What were the findings of Richard Holdaway’s research?

Maori settled more recently than previously thought.

The first Polynesian explorers formed permanent settlements.

Ship’s rats are the oldest rat species in the country.

Rats caused extinctions before any humans settled.

Questions 32–35

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Reading Passage 3?

In boxes 32–35 on your answer sheet, write

● YES – if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

● NO – if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

● NOT GIVEN – if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

32. The available research supports Holdaway’s theory but it has not been proved.

33. Nowadays, it is possible to totally destroy a population of rats on a small island.

34. Crook was the first person to recognize the potential of offshore islands as sanctuaries.

35. Tuatara numbers are continuing to fall.

Questions 36–40

Complete the summary using the list of words, A–H, below. Write the correct letter, A–H, in

boxes 36–40 on your answersheet.

What conclusions can we draw? The most important result of the tuatara research is that it

frees our 36 _______________. For example, there are many similarities between rats and 37

_______________. Should we now go further and consider reintroducing 38 _______________ to our

mainland rivers? Perhaps our children will come to believe in the 39 _______________ of species,

in the same way that our generation refuses to accept 40 _______________.

A natural evolution

B creative thought

C indigenous plants

�D trout

E pollution

F restoration

G native fish

H extinction

�1. TRUE

2. FALSE

3. NOT GIVEN

4. FALSE

5. cushion

6. rounded hood

7. lower back

8. 20 minutes

9. meditation room

10. music

11. traffic signal

12. co-workers

13. positive outcomes

14. C

15. E

16. A

17. F

18. B

19. D

20. pitch

21. friction

22. tone

23. drugs

24. roles

25. C

26. A

27. B

28. D

29. B

27. C

28. B

29. B

30. D

31. D

32. Yes

33. Yes

34. Not given

35. No

36. B

37. D

38. G

39. F

40. H