0% found this document useful (0 votes)

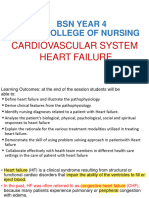

28 views24 pagesHeart Failure

The document provides a comprehensive overview of heart failure, specifically congestive heart failure (CHF), including its definition, classification, etiology, pathogenesis, morphology, and clinical features. It discusses the compensatory mechanisms of the cardiovascular system, the differences between left-sided and right-sided heart failure, and the associated morphological changes in various organs. The document emphasizes the progressive nature of CHF and its poor prognosis, outlining the clinical symptoms and systemic effects on the body.

Uploaded by

Aidam Love AtsuCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views24 pagesHeart Failure

The document provides a comprehensive overview of heart failure, specifically congestive heart failure (CHF), including its definition, classification, etiology, pathogenesis, morphology, and clinical features. It discusses the compensatory mechanisms of the cardiovascular system, the differences between left-sided and right-sided heart failure, and the associated morphological changes in various organs. The document emphasizes the progressive nature of CHF and its poor prognosis, outlining the clinical symptoms and systemic effects on the body.

Uploaded by

Aidam Love AtsuCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd