Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kerlerec's Cipher

Uploaded by

Donald E. PuschCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kerlerec's Cipher

Uploaded by

Donald E. PuschCopyright:

Available Formats

2008 by Donald E. Pusch. Some rights reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA.

[This article was originally published in Louisiana History, the quarterly publication of the Louisiana Historical Association (www.lahistory.org), vol. 49:46380.]

Kerlrec's Cipher: The Code Book of Louisiana's Last French Governor

By D O N A L D E. P U S C H

Louis Billouart de Kervasgan, chevalier de Kerlrec, was governor of French Louisiana from April 1752 to February 1763. During his tenure, Kerlrec sent several hundred dispatches to his superiors in France, particularly the Minister of the Marine, who at the time had broad administrative control over colonial affairs and was Kerlrec's primary link to the court of Louis XV. Many of these dispatchessome in codehave survived and are part of the French Archives Nationales series Colonies C13a, Correspondance l'arrive en provenance de la Louisiane, held today at the Centre des Archives d'Outre-Mer, Aix-en-Provence.1 During Kerlrec's term as governor, colonial affairs were heavily influenced by the Seven Years' War (1756-63) and its North American component, the French and Indian War (1754-63), and much of the governor's correspondence to the minister dealt with matters related to colonial defense. Because of the sensitivity of such matters and the danger of interception by the English,

The author is a retired lieutenant colonel, USAF, and former avionics integration manager for the Space Shuttle Orbiter secure communications system. He would like to thank colleague Pierre Mommessin for his many helpful suggestions during the preparation of this article. 1All references to documents in the Archives Nationales, Colonies C13a series are to the 1970 Library of Congress microfilm edition, referred to as the Louisiana Colonial Records Project (LCRP) and hereinafter cited as AN, C13a with register and folio number followed by LCRP reel number.

packets of official correspondence were, where possible, entrusted to the captains of departing French vessels. When this was not possible, dispatches were placed in the care of trusted passengers, often military officers returning to France. 2 These couriers had standing orders to throw the packets into the sea should their ships come into imminent danger of capture.3 For ships bearing French colors during this era, the peril of capture on the high seas was especially high. Between 1757 and 1762, the Marine Royale lost to the English some fifty-six of her ships-of-line and light frigates; almost three fourths of these vessels were captured intact. Losses among the Marine Royale's heavy supply ships (fltes, gabarres, and senaux) and freighted transports were at least as severe; and, owing to their light defenses, the great majority of those lost were captured intact. 4 On the circuit to and from Louisiana, significant captures included those of the Aimable Marthe, Marguerite, Trois Maries, and Fortun in 1756; the Marquis de Conflans, Concorde, and Bien Acquis in 1757; and the Victoire in 1758.5 Sensitive pieces of correspondence, especially those that could not be sent on ships of the king, were sometimes given the added protection of full or partial encryption, that is, the conversion of their original text into numerical cipher. Because encoding and decoding were time-consuming tasks, the use of cipher was reserved primarily for correspondence dealing with diplomatic or military matters. In the case of Kerlrec's dispatches, cipher was most often used to protect information dealing with Louisiana's defenses, the shortage of provisions and manufactured goods especially those needed as gifts for the Indiansor with military intelligence related to the English or their Indian allies. In a few

2In cases where returning French ships were not available, Kerlrec is known to have sent dispatches by way of Spain, Holland, and Denmark or through other French colonies such as Saint Domingue. Kerlrec to Minister, New Orleans, December 8, 1759. AN, C13a 41, folio 147-49vo, LCRP reel 48. 3The officer Duplessis, captured by an English corsair soon after sailing from New Orleans on the brigantine Flicit, mentions this orderand the execution of itin a report to the Minister of the Marine made soon after his release. Duplessis to Minister, Havana, January 25, 1757. AN, C13a 39, folios 302-03, LCRP reel 46.

statistics are based on data presented in Alain Demerliac, La Marine de Louis XV: Nomenclature des navires franais de 1715 1774 (Nice, 1995).

5Prize Papers, National Archives of the UK, Public Record Office, High Court of Admiralty (HCA 32); microfilm, Library and Archives Canada.

4These

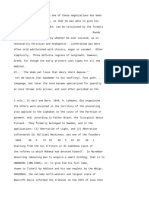

instances, cipher was also used to cloak Kerlrec's reports on the alleged misdeeds of other colonial officials and military officers. In their original form, Kerlrec's encoded dispatches pose an interesting problem: Aside from an occasional line or paragraph of readable text, their content appears simply as rows of numbers separated into groups of one, two, or three digits. An example of this can be seen in Kerlrec's dispatch no. 215 to the Minister of the Marine, the first several lines of which are reproduced below.6

A portion of Kerlrec's encoded dispatch no. 215

When a letter like this reached France, it was processed by a cipher clerk at the Ministry of the Marine and converted into lines of readable text, which were then added as interlineations on the original document. Most of Kerlrec's encoded dispatches bear such annotations. Encoding or decoding a dispatch required the use of a code book containing the cipher. The one used by Kerlrec has not survived; however, clues as to what it contained can be found by carefully examining examples of the governor's encoded dispatches. For this article, the author analyzed thirty-three such dispatches, all that could be found in the Colonies' C13a series and elsewhere, and from that analysis was able to recreate most of

6Kerlrec to Minister, New Orleans, September 17, 1759. AN, C13a 41, folio 111-11vo, LCRP reel 48.

Kerlrec's code book.7 This was then reapplied to the encoded dispatches to produce the author's own decoded versions of the originals.8 A listing of the dispatches used in this analysis is shown in Table 1. To understand the encoding system used in the Kerlrec dispatches, it is helpful to consider a few basic concepts of cryptography, the first involving a simple system of substitution. For example, if one wanted to encode the message, "Les Anglais viennent," one scheme might be to assign every letter of the alphabet a number: A = 1, B = 2, C = 3, etc. Through this scheme, the original "plaintext" message could be converted into an encoded message containing only code numbers, referred to as "ciphertext" or "codetext." L-E-S A-N-G-L-A-I-S V-I-E-N-N-E-N-T

12-5-19 1-14-7-12-1-9-19 22-9-5-14-14-5-14-20 The specific assignment of numbers to letters is referred to as the "cipher code." To enhance the security of such a scheme, the cipher code could be changed from time to time, so long as both the sender and the receiver used identical code books. The sciencesome would say artof "cracking" such codes is referred to as "cryptanalysis." As one might suspect, a simple coding scheme such as that given in the example would be highly vulnerable to cryptanalysis. It is known, for example, that in a thousand words of typical French text of the type appearing in the Kerlrec dispatches, the letter e (diacritics ignored) will occur approximately 805 times; the letter a, 326 times and so on for the entire alphabet.9 Thus, given enough ciphertext, one could use frequency analysis of the code numbers to decipher many of the letter-number pairs that make up the cipher code. Other characteristics of the language can also aid the cryptanalyst; for exam-

7One dispatch, no. 144, which was also included in the analysis, was found in Manuscrit no. 31 du catalogue de La Roncire, folio 299-300, Bibliothque du port de Brest, now held at the Archives Nationales. LCRP reel 1.

author is indebted to colleague C. David Lodge for development of the software filter used in the decoding process.

9These statistics are based on the author's own analysis of documents from the AN, C13a series, the sample set consisting of 10,276 words.

8The

ple, in English as well as in French, the letter q will almost invariably be followed by the letter u. The coding scheme used in Kerlrec's dispatches was considerably more complex than the scheme used in the example; however, its basic structure was fairly easy to determine, as similar schemes (with different cipher codes) were in use at the same time by French officials in Canada and had been used a decade earlier in Louisiana by Kerlrec's predecessor, Pierre Franois de Rigaud, marquis de Vaudreuil.10 The scheme used in all of Kerlrec's encoded dispatches was found to be of a type known as a two-part nomenclator, a system invented by Antoine Rossignol, cryptographer to the court of Louis XIV. According to traditional accounts, one version of Rossignol's encoding scheme was lost to historians until the latter part of the nineteenth century, when tienne Bazeries, a member of the French army's cryptographic service, managed to crack the code, illuminating a number of the Sun King's previously unreadable documents.11 In the particular two-part nomenclator used in the Kerlrec dispatches, code numbers were assigned to individual letters, word fragments, or entire words of plaintext, for example:12 btiment ....... 293 tre................ 147 Hollande ....... 459 pas................... 20 prsent............ 68 s ...........49 or 207 secours............ 81 fi.................... 570 u.................... 258 votre ............. 278

10Code tables created in 1757 for Vaudreuil, then governor-general of New France, and in 1758 for the Marquis de Montcalm are in AN, C11e 10, folio 28590vo (Centre des Archives d'Outre-Mer), microfilm, Library and Archives Canada, reel F-408. Code tables created in 1742 for Vaudreuil, then governor of Louisiana, are in Maurepas to Vaudreuil, October 22, 1742, Vaudreuil Papers, Loudoun Collection, Huntington Library, Art Collection, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California), microfilm. These latter code tables fell into the hands of the English in 1755 when the sixty-four-gun warship Alcide was captured. Bill Barron, The Vaudreuil Papers: A Calendar and Index of the Personal and Private Records of Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, Royal Governor of the French Province of Louisiana, 1743-1753 (New Orleans, 1975), xi. 11Simon Singh, The Code Book: The Science of Secrecy from Ancient Egypt to Quantum Cryptography (London, 1999), 55-8. 12In the two-part nomenclator system, the code elements need not be numbers. Letters or a combination of letters and numbers could also be used. The code elements used in Kerlrec's correspondence were always numbers.

Coding and decoding documents each requires a separate table: The firstthe table chiffreris an alphabetically ordered list of the plaintext elements (the letters, word fragments, or whole words) shown with their code-number counterparts (the one-, two-, or three-digit numbers). The secondthe table dchiffrercontains all of the same data but is sorted on the code numbers. As the names imply, the first table is used for encoding; the second, for decoding. Determining the exact cipher code used by Kerlrec could be quite difficult were it not for the fact that plaintext versions decoded at the Ministry of the Marineexist for most of the governor's encoded dispatches from the Colonies C13a series. Each such dispatch provides what is essentially a Rosetta Stone for the cryptanalyst, offering up bits and pieces of the cipher code for collection into the recreated code book. Of the thirty-three encoded dispatches analyzed by the author, plaintext versions exist for thirty, and these could be used to support recreation of the code book. It was then possible to use the code book to verify the decoding performed by the ministry and to decode the three dispatches for which no plaintext versions are extant.13 Kerlrec's cipher contained 700 pairs of code numbers and their corresponding plaintext letters, word fragments, whole words, or nulls, the latter arising from the existence of code numbers that had no corresponding plaintext.14 The elements of the code identified by the authora total of 547are displayed in Table 2 at the end of this article in the form of a table dchiffrer (decoding table). To find the 153 missing code pairs would simply require the examination of more coded, annotated documents, if such could be found. In addition to the basic protection afforded by encoding, there were other useful security features of Kerlrec's two-part nomenclator. First, to confound frequency analysis, some of the more commonly used letters of the alphabet could be encoded in

13The dispatches that contain code for which no corresponding plaintext exists are nos. 206 (Kerlrec to Minister, New Orleans, July 3, 1759, AN, C13a 41, folio 81-82), 207 (Kerlrec to Minister, New Orleans, July 13, 1759, AN, C13a 41, folio 87-98vo), and 215 (Kerlrec to Minister, New Orleans, September 17, 1759, AN, C13a 41, folio 111-11vo). 14Vaudreuil's 1742 code tables cited at note 10 provided for fifteen such null code numbers.

two ways. The letter s, for example, could be encoded as either 49 or 207; the letter a, as either 114 or 366. Altogether, double codes were available for nine letters: a, c, d, e, l, n, o, r, and s. A second security feature permitted whole words to be encoded in different ways. For example, the word particulier could be represented by a single code number (124), or it could be broken into fragments (parti-cu-li-er) and each fragment encoded (568.208.260.495). A third feature had to do with the existence of null code numbers. Having no corresponding plaintext, these nulls could be inserted in the encoded document at random locations, providing false clues to the would-be code breaker. Finally, spaces between words were not coded and there was no separate coding for capital letters, punctuation, or diacritics, making difficult the task of picking out individual letters, words, phrases, or sentences. The reason why this particular scheme was used arises from a very practical consideration: In general, the selection of an encoding system is a compromise between ease of use and security, and the two-part nomenclator is a fairly balanced compromise.15 It is easy to use, requiring only a simple look-up in the table chiffrer (for encoding) or the table dchiffrer (for decoding). Also, a single error made during encoding would result in the corruption of only one letter, word fragment, or word in the decoded document, something that was not the case with other, more complex, encoding schemes.16 The two-part nomenclator could also be quite secure provided that occasional changes were made to the cipher code and full advantage was taken of the various security features inherent in the system. In practice, however, it was found that Kerlrec's two-part nomenclator was not always used to its best advantage. First, it was discovered that all of the encoded dispatches examined in this study were encrypted using the same cipher code. This was a serious weakness. If, in 1755, the English had gained access to even a few plaintext versions of the governor's encoded documents, the cipher could have been broken and any such document

15Much more secure systems than the two-part nomenclator existed, for example, the polyalphabetic substitution systems of Blaise de Vigenre introduced a hundred years earlier. Their use, however, was much more tedious and timeconsuming. David Kahn, The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing, rev. ed. (New York, 1996), 146-50. 16In systems such as Vigenre's, a small error made during encoding could result in total corruption of the document during decoding. Ibid.

intercepted through 1762 would have been compromised. 17 Why the cipher code was not changed during a period of over seven years remains a mystery. Perhaps creating, distributing, and administering new code tables was simply too much of an administrative burden for the Ministry of the Marine. A second, very serious, weakness had to do with the manner in which Kerlrec's cipher clerk used the code book to construct the encoded dispatches. As mentioned previously, certain letters of the alphabet could be represented by two different code numbers. The idea was to alternate between the two numbers so as to mask the frequency of occurrence of the corresponding letters. In practice, the cipher clerk almost always used both code numbers together, one atop the other. This is why, in the dispatch extract shown at the beginning of this article, one finds the code number 178 atop the code number 660 (representing the letter e), 114 atop 366 (representing the letter a), 49 atop 207 (representing the letter s), and 180 atop 230 (representing the letter r). Apparently, when the cipher clerk looked up these letters in the table chiffrer and found two numbers listed, he simple wrote down both of them and in this way unwittingly nullified the intent of this security feature. Also, although it is strongly suspected that null code elements were included in Kerlrec's code book, none was used in any of the encoded documents examined in this study. Poor security practices were not limited to the encryption process. At the ministry, when an encoded dispatch was received and decrypted, the resulting plaintext was annotated directly onto the original ciphertext version, and evidence suggests that such parallel texts were then circulation within the ministry. 18 For an enemy, having access to these parallel texts would have been the next best thing to having access to the code book. A more secure practice would have been to decode each dispatch into a separate document and then to destroy or separately archive the encoded version.

17The author was able to recover about 45 percent of Kerlrec's cipher code through the analysis of just one, six-page document.

of Kerlrec's encoded dispatches were circulated to Commissaire de la Marine Jean Augustin Accaron and others, as evidenced by their names or initials on the documents. Also, the presence of abstracts at the top of some dispatches suggests that they were screened by lower-level officials prior to reaching the Minister. See, for example, Kerlrec to Minister, New Orleans, June 24, 1755. AN, C13a 39, folio 104-6vo, LCRP reel 46.

18Several

The analysis and recreation of Kerlrec's cipher allows, for the first time, a way to verify the accuracy with which the Ministry of the Marine decrypted the subject dispatches. In the course of this investigation, the author, using the recreated code table, independently decrypted each of the thirty-three dispatches and then compared the results to the plaintext versions prepared by the ministry. This brought to light a number of errors in the ministry's versions. In dispatch no. 86, dated October 9, 1755, Kerlrec describes the location of newly established English posts in Georgia.19 The ministry's decoded version reads, in translation, "They have just established settlements on a river two day's [journey] from the Kaoitas. . . ." An examination of the code, however, reveals a more exact description: "They have just established settlements on the Okkonis River, two day's [journey] from the Kaouyta. . . ." In dispatch no. 91, dated October 18, 1755, Kerlrec speaks to the shortages of cannoneers in Louisiana. 20 The ministry's decoded version reads, "As for cannoneers, we have asked for them for the [lower Mississippi] river as well as for Mobile." The actual code conveys a very different message: "As for cannoneers, we have only one for the entire river and one other at Mobile." The mechanism by which some such decoding errors were made is often quite apparent. For example, while decoding the fourth page of dispatch no. 86, the ministry's cipher clerk lost his place in the document and skipped from the end of line 11 to the end of line 12, failing to decode the intervening ciphertext.21 The ministry's version reads, "I repeat to you again, Your Grace, the essential needs for artillery according to the table of the posts. . . ." The code, however, reads, "I repeat to you again, Your Grace, the essential needs of the colony, which consist of artillery according to the table of the posts. . . ." Translations of several of Kerlrec's encoded dispatches have been previously published. Most notably, seventeen of the thirtytwo contained in the Colonies C13a series appear in translation

19Kerlrec to Minister, New Orleans, October 9, 1755. AN, C13a 39, folio 6062vo, LCRP reel 46.

to Minister, New Orleans, October 18, 1755. AN, C13a 39, folio 6970vo, LCRP reel 46.

21Kerlrec to Minister, New Orleans, October 9, 1755. AN, C13a 39, folio 6062vo, LCRP reel 46.

20Kerlrec

10

in the fifth volume of Mississippi Provincial Archives.22 Those translations, however, were made from the decoded versions prepared by the Ministry of the Marine, not from the original ciphertext. Thus, decoding errors made by the ministry were carried forward in the translations. Consider, for example, Kerlrec's dispatch no. 150, dated October 21, 1757, in which the governor described the first work done at the site of Fort Ascension, later renamed Fort Massiac. 23 The translation appearing in Mississippi Provincial Archives indicates that the fort was "reinforced with stone."24 This is in agreement with the ministry's decoded version, which describes the fort as de pierre rendoubl. The ciphertext, however, is 116.169.347.230.567.642.497.483., which is de pieux rendoubl, meaning "reinforced with pickets." A similar error can be found in dispatch no. 135, dated January 28, 1757, in which Kerlrec speaks of his inability to provide trade goods to the Indians.25 The translation appearing in Mississippi Provincial Archives reads, "If the Abnakis keep their word with us, I shall be much more embarrassed." 26 This agrees with the ministry's decoded version but propagates an error involving the name of the Indian tribe. The code is 95.626.26.596, which is not Abnakis, but Cheraki (Cherokee). Another example is found in dispatch no. 308, dated June 24, 1762.27 In one part of the dispatch, Kerlrec speaks of having sent Sieur Lantagnac to the Cherokee nation. The translation appearing in Mississippi Provincial Archives reads, ". . . I ordered him to have my letters passed on to the Illinois so that he might carry out the same operations among the nations that surround it."28 This is in general agreement with the ministry's decoded

22Mississippi Provincial Archives: French Dominion, Dunbar Rowland, A. G. Sanders, and Patricia Kay Galloway, eds., 5 vols. (Baton Rouge, 1984), vol. 5. 23Kerlrec to Minister, New Orleans, October 21, 1757. AN, C13a 39, folio 27779vo, LCRP reel 46. 24Mississippi 25Kerlrec

Provincial Archives, 5:188-90.

to Minister, New Orleans, January 28, 1757. AN, C13a 40, folio 27-8, LCRP reel 47.

26Mississippi 27Kerlrec

Provincial Archives, 5:180.

to Minister, New Orleans, June 24, 1762. AN, C13a 43, folio 78-83, LCRP reel 51.

28Mississippi

Provincial Archives, 5:278-80.

11

version; however, the original ciphertext carries a slightly different meaning: ". . . I ordered him to have my letters forwarded to the Illinois [post] for M. de Neyon, who commands there, so that he takes the same action toward the nations that surround him." Decoding errors were not the only ones identified. In several of the dispatches, errors were made during the coding process. This is easy to understand when one considers that three or four copies of each dispatch might be produced, each involving the mindnumbing task of copying line after line of code numbers. The most frequent error was the transposition of digits, for example, 652 (ca) for 562 (ac). Another, somewhat less common, error was the omission or repetition of code elements. It also appears that some code elements were omitted on purpose, perhaps because the cipher clerk judged them unnecessary. For example, in dispatch no. 72, dated June 24, 1755, the code for s (49 or 207) was omitted at the end of almost all of the plural nouns and adjectives.29 For the most part, such transpositions, repetitions, or omissions were easily recognized and could be corrected by the ministry's cipher clerk during decoding. Despite the relatively unsophisticated nature of Kerlrec's cipher, the weaknesses in the way it was used, and the introduction of errors during the coding or decoding processes, the system seems to have worked well enough. If nothing else, it kept sensitive documents from being easily read by the couriers, ship's officers, clerks, and others who might have handled them while in transit. This was the case, for example, with correspondence dealing with internal issues not specifically related to the colony's security. Toward the end of 1758, a dispute arose between Kerlrec and the newly arrived ordonnateur, Vincent de Rochemore, that came to be known in France as the Affaire de la Louisiane, entailing the exchange of charges and countercharges between the two and the formation, among the military and civilian officers in New Orleans, of camps loyal to one or the other of the two belligerents.30 Four of Kerlrec's encoded dispatches deal with this subject. One in particular, dispatch no. 206, dated July 3, 1759, is devoted entirely to the behavior of Rochemore and

to Minister, New Orleans, June 24, 1755. AN, C13a 39, folio 10406vo, LCRP reel 46.

30For an exhaustive treatment of the subject, see Herv Gourmelon, Le Chevalier de Kerlrec, 1704-1770: L'affaire de la Louisiane . . ., 2nd ed. (Paris, 2004).

29Kerlrec

12

those loyal to him and requests their recall to France.31 For that particular dispatch, encoding was used because the document was to be entrusted to a Spanish priest bound for Havana and would, no doubt, have passed through many hands before reaching the Minister of the Marine. It is difficult to judge how effective Kerlrec's code was in keeping military matters secret, but there was certainly a need to do so. Early in the Seven Years' War, the English had made plans to invade Louisiana, and in February 1758 an actual authorization for such action had been conveyed to Gen. Jeffrey Amherst.32 Certainly the colony was ripe for such an invasion. It is evident, considering just the intelligence contained in Kerlrec's encoded dispatches that, throughout the period of the Seven Years' War, Louisiana was perpetually short of resources, constantly struggling to hold onto its Indian allies, and would have been all but defenseless against a determined English attack, especially one supported by naval forces directed at either Mobile or New Orleans. We find, for example, in Kerlrec's coded dispatch of July 13, 1759one of the three for which no plaintext annotations have been foundthat the Balize post, built originally to guard the primary entrance into the Mississippi River, had been stripped of all its cannons, save two for signaling, and the commander there had been directed to abandon the post in the event of an English attack.33 The fact that the English failed to exploit this and other such vulnerabilities may be due, at least in part, to the effectiveness of Kerlrec's cipher.

31Kerlrec to Minister, New Orleans, July 3, 1759. AN, C13a 41, folio 81-2, LCRP reel 48. 32Pitt to Amherst, Whitehall, February 10, 1759, published in Gertrude S. Kimball, ed., Correspondence of William Pitt, When Secretary of State, with Colonial Governors and Military and Naval Commissioners in America, 2 vols. (London, 1906), 2:37-8. 33Kerlrec to Minister, New Orleans, July 13, 1759. AN, C13a 41, folio 87-98vo, LCRP reel 48.

13

Table 1. Dispatches used in the author's analysis34

Dispatch number 72 86 87 91 103 117 127 135 138 141 143 144 145 146 150 194 194 206 207 215 226 228 236 245 247 256 263 277 279 284 308 332 Copy number 1 1 2 2 1 3 2 3 3 1 3 1 1 1 2 2 3 1 2 1 2 1 1 1 3 2 2 1 1 2 1 Date June 24, 1755 October 9, 1755 October 10, 1755 October 18, 1755 April 1, 1756 July 22, 1756 December 12, 1756 January 28, 1757 March 13, 1757 March 16, 1757 May 12, 1757 May 13, 1757 August 28, 1757 September 10, 1757 October 21, 1757 August 12 and 23, 1758 May 6, 1759 November 10, 175935 July 3, 1759 July 13, 1759 September 17, 1759 December 8, 1759 June 12, 1760 March 30, 1760 December 21, 1760 March 1, 1761 June 8, 1761 July 12 and 19, 1761 December 15, 1761 February 10, 1762 April 28, 1762 June 24, 1762 July 26, 1762 A.N., Colonies C13a reference 39, folio 104-6vo 39, folio 60-62vo 39, folio 63-64 39, folio 69-70vo 39, folio 146-48 39, folio 181-82 39, folio 190-91 40, folio 27-28 39, folio 258-59 39, folio 262-63 39, folio 246-46vo [See note 7] 40, folio 34-35vo 39, folio 247-49 39, folio 277-79vo 40, folio 31-33vo 41, folio 51-52vo 41, folio 144-45vo 41, folio 81-82 41, folio 87-98vo 41, folio 111-11vo 41, folio 147-49vo 42, folio 48-53 42, folio 10-11vo 42, folio 83-85vo 42, folio 203-4 42, folio 217-20 42, folio 229-30 42, folio 267-69 43, folio 25-25vo 43, folio 30-32vo 43, folio 78-83 43, folio 90-91 LCRP Reel no. 46 46 46 46 46 46 46 47 46 46 46 1 47 46 46 47 48 48 48 48 48 48 50 50 50 50 50 50 50 51 51 51 51

34All dispatches except no. 146 are those of Kerlrec. Dispatch no. 146 is a joint dispatch drafted with Jean Baptiste Claude Bob-Descloseaux, then performing the functions of ordonnateur in the colony. 35Except for its date and formatting, this dispatch is identical to Kerlrec's dispatch of May 6, 1759. It does not, however, contain plaintext annotations.

14

Table 2. Kerlrec's Cipher A partial recreation of the table dchiffrer used for Kerlrec's correspondence during the period 1755-176236

2 4 5 6 9 12 14 16 17 19 20 22 24 26 27 28 29 32 33 34 35 36 37 39 41 42 43 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 indispensable convenable obstacle semblable tour voyage ar ai entreprise el pas comman projet k force bi quand beaucoup guerrier vo peut feu pays praticable hiver homme opration roit ois cha du s ce op quelle dont son he sou idee le 60 61 62 63 64 65 68 71 72 73 75 76 78 79 80 81 82 84 86 87 88 89 90 92 93 95 96 97 98 99 100 102 103 104 105 106 108 109 111 113 114 p frappe grace to elle fort prsent im tu magazin gi l ete regle il secours prochain honneur ru tranquil isle c tant borne ennemi che marchandise nouvelle rend Chactas pour munition gout notre tout encore nos je prompt mouvement a 115 116 117 118 119 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 144 145 146 147 149 150 151 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 163 164 vi de ent qui la Louisiane usage qu particulier fais al franois plusieurs l seul poste terre place egal q vers troupe nt chose ailleurs pe suite h extraordinaire etre port habitant co ga oc la Vera Cruz di ir fe deffen sorte plan

36In reconstructing the code table, the author used word or word-fragment spellings that were consistent with the orthography of the time. Thus, franois instead of franais and anglois instead of anglais, the ending -ais(e) not being formally adopted until the sixth edition (1835) of the Dictionnaire de l'Acadmie franaise.

15 165 166 167 168 169 172 175 177 178 180 181 183 184 185 186 187 189 190 191 192 195 196 197 198 199 200 202 204 205 206 207 208 210 211 212 213 214 216 218 219 220 221 222 223 224 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 recu etat haut depuis pi service non nul e r fidlit verifi droit et fait z Espagne pre malheur interet bli savoir em considrable n objet corsaire ncessaire jamais puis s cu ecri genie impatience succes Anglois nation for fin sauvage la Jamaque lettre tien be libre g peu ils bon r dtachement m 233 235 236 237 238 240 241 242 243 244 245 247 249 250 252 253 254 255 256 257 258 259 260 261 262 263 264 265 266 267 268 269 271 272 273 274 275 277 278 279 281 283 284 285 286 288 289 290 292 293 294 296 297 aucun per meilleur hi ont Cuba bre assez tabli quel d ordre doi o effort difficulte Mexique infor at dj u St-Domingue li po incursion ouil t ho les oi enfin vu employ marque espagnol ge pris, prix par votre roy gouvernement paix se ton avec ex nu point nombre btiment trai in ve 298 299 300 301 302 303 304 305 306 307 308 309 310 311 313 314 315 316 318 320 321 323 325 327 328 329 330 331 334 335 336 337 339 340 341 342 344 345 346 347 349 350 351 352 353 356 358 361 362 363 365 366 367 la Mobile es France vaisseau ouvrage premier ment ngre cour go na autre so fusil decla monde on Nouvelle Orlans occasion nom batterie arme si conduite barri introdu fortifi allie f retard ordinaire depen faire eu querelle approuve aux vous do eux pu con ncessit depart y bou gnral loin mer charge affaire a aussi

16 368 369 370 371 374 375 376 378 379 380 381 383 384 385 387 388 389 390 391 394 395 396 398 399 401 402 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 412 414 415 416 417 419 420 421 423 426 427 428 430 431 432 433 434 435 440 lors hors ne fo flte celle fer monsieur jour obser disposition farine gagne faute juge vrai desti au escadre fois hu ro traite entre prcaution rivire appo main soin re que avis jusques te ja ri loi Illinois nous v danger ensemble transport tion oit habi garde moyen intelligence ville Danemark aprs pendant 441 442 443 444 445 446 447 448 449 450 452 455 456 457 458 459 461 462 463 464 466 467 468 469 470 471 473 474 476 477 478 479 480 481 482 483 484 485 486 487 488 490 492 493 494 495 497 498 499 500 501 502 503 soupon majest fleuve long un compte qu'il mi cas don oblige possible lo su pai Hollande voir habitation officier infini mal raison sujet quantit meme n tres quer quelque frgate vent va ordon certain fa ble prtexte canon vie bruit artillerie sur situation crainte aim er ou qualit ni des juste ressource garnison 504 505 506 507 509 510 511 512 513 514 515 516 517 518 519 522 523 524 525 526 528 529 530 531 532 534 535 536 537 538 539 540 541 542 544 546 547 549 550 551 554 555 557 558 559 562 564 565 566 567 568 569 570 arrangement om sans avant me rien blo manage ferme j coup ces x fu b ainsi attaque faveur oient bo os ap lui igno sentiment fier Chicachas ci uti hostilit conseil ab nouveau bla bu afin la est croi Alibamous mo besoin menace ma dans ac lieu concert question en parti guerre fi

17 572 573 574 575 577 578 579 580 581 582 583 584 588 589 590 592 593 594 595 596 597 599 600 601 602 603 604 605 606 607 608 609 610 611 612 614 chevelure ta demande fond faon soldat forme heure consquence or gens la Balize ti grand inaction vnement incessamment temps ob i environ sa mu quoique envoy no souvent expres jo gre suivant comme circonstance ustensiles quartier raport 615 616 617 619 620 621 622 623 625 626 627 628 629 632 635 636 637 638 639 641 642 644 645 647 648 649 650 651 652 653 654 655 656 657 658 660 gu risque liaison ba diffrent barque trahison an important ra mais vin Angleterre nanmoins mauvais voi da tous trop poudre d dernier Havanne c leur inconvnient am toujours ca ju bien voye colonie foible contre e 661 662 663 665 666 668 669 670 671 672 673 674 675 676 677 678 679 680 681 682 683 684 685 686 687 688 689 690 692 694 696 697 698 699 surplus favorable vain propos doute bateau chef brique ha pa ceux augmen quant fide lu doit rciproque tre moins laisse hazard o plus intention quoi egard livre dtail la Caroline endroit mesure secret gouverneur marchand

You might also like

- Fighting Instructions, 1530-1816: Publications of the Navy Records Society Vol. XXIXFrom EverandFighting Instructions, 1530-1816: Publications of the Navy Records Society Vol. XXIXNo ratings yet

- Early Aristocratic Seals: An Anglo-Norman Success Story : Jean-François NieusDocument25 pagesEarly Aristocratic Seals: An Anglo-Norman Success Story : Jean-François NieusIZ PrincipaNo ratings yet

- Acc7840 6411Document4 pagesAcc7840 6411Faith ViernesNo ratings yet

- Napoleon's Imperial Guard Uniforms and Equipment. Volume 1: The InfantryFrom EverandNapoleon's Imperial Guard Uniforms and Equipment. Volume 1: The InfantryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Cryptology of The German Intelligence ServicesDocument38 pagesThe Cryptology of The German Intelligence ServiceseliahmeyerNo ratings yet

- 'Napoleon is Dead': Lord Cochrane and the Great Stock Exchange ScandalFrom Everand'Napoleon is Dead': Lord Cochrane and the Great Stock Exchange ScandalNo ratings yet

- Econ1984 7251Document4 pagesEcon1984 7251Danny ZambranoNo ratings yet

- Snaassign9843 5679Document4 pagesSnaassign9843 5679Arsalan JahaniNo ratings yet

- Acc9070 8669Document4 pagesAcc9070 8669Sahil KumarNo ratings yet

- First Rate: The Greatest Warship of the Age of SailFrom EverandFirst Rate: The Greatest Warship of the Age of SailRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Bio4739 7389Document4 pagesBio4739 7389Jason MalikNo ratings yet

- With "The Thirty-Second" In The Peninsular And Other CampaignsFrom EverandWith "The Thirty-Second" In The Peninsular And Other CampaignsNo ratings yet

- Three Frenchmen in Bengal 1Document124 pagesThree Frenchmen in Bengal 1Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- The Classical Association, Cambridge University Press Greece & RomeDocument16 pagesThe Classical Association, Cambridge University Press Greece & RomeDominiNo ratings yet

- The Depot for Prisoners of War at Norman Cross Huntingdonshire 1796 to 1816From EverandThe Depot for Prisoners of War at Norman Cross Huntingdonshire 1796 to 1816No ratings yet

- Eco7636 1691Document4 pagesEco7636 1691Bayu AjiNo ratings yet

- History - 2023 - ROCHE - Elizabethan Catholic Intelligencers Spain and The Armada of 1597Document18 pagesHistory - 2023 - ROCHE - Elizabethan Catholic Intelligencers Spain and The Armada of 1597Vratislav ZervanNo ratings yet

- Psy5750 3693Document4 pagesPsy5750 3693Kathleen Ivy AlfecheNo ratings yet

- The Campaign of Trafalgar — 1805. Vol. II.From EverandThe Campaign of Trafalgar — 1805. Vol. II.Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Warships of the Napoleonic Era: Design, Development and DeploymentFrom EverandWarships of the Napoleonic Era: Design, Development and DeploymentRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Hist8728 4421Document4 pagesHist8728 4421Kimchee StudyNo ratings yet

- Acc8901 7955Document4 pagesAcc8901 7955John Paul CabreraNo ratings yet

- The Master Shipwright's Secrets: How Charles II built the Restoration NavyFrom EverandThe Master Shipwright's Secrets: How Charles II built the Restoration NavyNo ratings yet

- Ch00 (Cryptography History)Document40 pagesCh00 (Cryptography History)hunter nullNo ratings yet

- Eng9150 4358Document4 pagesEng9150 4358Muhammad FauzanNo ratings yet

- 13 Sharks: The Careers of a Series of Small Royal Navy Ships, from the Glorious Revolution to D-DayFrom Everand13 Sharks: The Careers of a Series of Small Royal Navy Ships, from the Glorious Revolution to D-DayRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Econ2971 8916Document4 pagesEcon2971 8916232.Komang Adi Sanjaya PutraNo ratings yet

- Science409 2834Document4 pagesScience409 2834ganetaNo ratings yet

- Fireship: The Terror Weapon of the Age of SailFrom EverandFireship: The Terror Weapon of the Age of SailRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Math6821 3873Document4 pagesMath6821 3873HayeNo ratings yet

- Phys617 4281Document3 pagesPhys617 4281Desiree QuiambaoNo ratings yet

- Eng8206 1023Document4 pagesEng8206 1023Hax MonNo ratings yet

- Soc819 6946Document4 pagesSoc819 6946Mandz MooreNo ratings yet

- Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period: Illustrative DocumentsFrom EverandPrivateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period: Illustrative DocumentsNo ratings yet

- Three Musketeers (Boys' & Girls' Library)From EverandThree Musketeers (Boys' & Girls' Library)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3812)

- Math 8464Document4 pagesMath 8464rizqi mirzaqulNo ratings yet

- Three Frenchmen in Bengal The Commercial Ruin of the French Settlements in 1757From EverandThree Frenchmen in Bengal The Commercial Ruin of the French Settlements in 1757No ratings yet

- History of CryptographyDocument40 pagesHistory of CryptographyMuhammad NadeemNo ratings yet

- Armada Guns: The Mariner's MirrorDocument24 pagesArmada Guns: The Mariner's MirrorVeratrin DyeNo ratings yet

- Psy1448 3732Document4 pagesPsy1448 3732Eric LimNo ratings yet

- Eng8384 1234Document4 pagesEng8384 1234Alyssa OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Soc5254 5428Document4 pagesSoc5254 5428aliaNo ratings yet

- Science2984 7818Document4 pagesScience2984 7818Rika MishaNo ratings yet

- Inflasi4433 7098Document4 pagesInflasi4433 7098FF ErizNo ratings yet

- Bio7288 4036Document4 pagesBio7288 4036oleNo ratings yet

- System4253 7187Document4 pagesSystem4253 7187faizin ahmadNo ratings yet

- Sos6229 1438Document4 pagesSos6229 1438Akbar RahmanNo ratings yet

- Bomag bw100 - 120 Ad - Ac 3 Bw125adh bw135 - 138 Ad Ac c747b c754b Circuit Diagram Drawing No 78100130 2003 eDocument22 pagesBomag bw100 - 120 Ad - Ac 3 Bw125adh bw135 - 138 Ad Ac c747b c754b Circuit Diagram Drawing No 78100130 2003 emorganweiss270691imz100% (68)

- Iberville's CanadiansDocument31 pagesIberville's CanadiansDonald E. Pusch100% (3)

- Vaudreuil's Code BookDocument6 pagesVaudreuil's Code BookDonald E. PuschNo ratings yet

- Duplessis' Report On Louisiana, 1757Document12 pagesDuplessis' Report On Louisiana, 1757Donald E. PuschNo ratings yet

- Le Mot NouvsteDocument4 pagesLe Mot NouvsteDonald E. PuschNo ratings yet

- The Service Dossier of Pierre Thiton de SillègueDocument4 pagesThe Service Dossier of Pierre Thiton de SillègueDonald E. PuschNo ratings yet

- Ship Logs at Clayton LibraryDocument2 pagesShip Logs at Clayton LibraryDonald E. PuschNo ratings yet

- Employees of The Marine in The Colony of Louisiana, 1759Document26 pagesEmployees of The Marine in The Colony of Louisiana, 1759Donald E. Pusch100% (2)

- The Capture of The Chariot Royal, 1756Document8 pagesThe Capture of The Chariot Royal, 1756Donald E. Pusch100% (1)

- ANOM, Colonies C13A 39, Fol. 302-3Document5 pagesANOM, Colonies C13A 39, Fol. 302-3Donald E. PuschNo ratings yet

- Detail Du Combat de La Flute Du Roy Le Chariot RoyalDocument3 pagesDetail Du Combat de La Flute Du Roy Le Chariot RoyalDonald E. Pusch100% (1)

- Log of The Torbay, November 30, 1758Document1 pageLog of The Torbay, November 30, 1758Donald E. PuschNo ratings yet

- A.N., Marine C7 280 - Rochemore Service RecordDocument2 pagesA.N., Marine C7 280 - Rochemore Service RecordDonald E. PuschNo ratings yet

- Deposition of Jean François Large, 1756Document3 pagesDeposition of Jean François Large, 1756Donald E. PuschNo ratings yet

- A.N., Marine B4 104, Fol. 228Document10 pagesA.N., Marine B4 104, Fol. 228Donald E. Pusch100% (2)

- A Review Paper On CryptographyDocument5 pagesA Review Paper On CryptographycikechukwujohnNo ratings yet

- CNS LabmanualDocument21 pagesCNS LabmanualakiraNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 - CSDocument86 pagesUnit 2 - CSyuydokostaNo ratings yet

- The Playfair CipherDocument2 pagesThe Playfair Ciphernav1991navNo ratings yet

- Cryptography, Network Security and Cyber Laws Notes 2019-2020Document23 pagesCryptography, Network Security and Cyber Laws Notes 2019-2020Himanshu KumarNo ratings yet

- Network Security & Cryptography Lecture 5 & 6Document66 pagesNetwork Security & Cryptography Lecture 5 & 6Udhay PrakashNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice E-CommerceDocument13 pagesMultiple Choice E-CommerceChaii Chai67% (3)

- Lect 2Document27 pagesLect 2abhs82No ratings yet

- Assignment 1-Vignesh Prasad VDocument14 pagesAssignment 1-Vignesh Prasad VVignesh Veera Prasad100% (1)

- COMP3334 Mid-Term 2223 Sample SolutionsDocument8 pagesCOMP3334 Mid-Term 2223 Sample SolutionsFouillandNo ratings yet

- Cryptosummary PDFDocument2 pagesCryptosummary PDFMichelleNo ratings yet

- Introduction, Basics of Cryptography, Secret Key CryptographyDocument48 pagesIntroduction, Basics of Cryptography, Secret Key CryptographySudha SreedeviNo ratings yet

- Polygraphic SubstitutionDocument2 pagesPolygraphic SubstitutionSiddhant GargNo ratings yet

- Quiz - 1 PDFDocument11 pagesQuiz - 1 PDFniviNo ratings yet

- Instructor: DR - Maaz Bin Ahmad. 0333-5264960: Maaz@pafkiet - Edu.pkDocument54 pagesInstructor: DR - Maaz Bin Ahmad. 0333-5264960: Maaz@pafkiet - Edu.pkSubhan50No ratings yet

- Is CombinedDocument566 pagesIs Combinedlolzcat3454No ratings yet

- CrypTool Lab F08Document6 pagesCrypTool Lab F08huyloccs0% (2)

- Data Encryption Techniques and StandardsDocument59 pagesData Encryption Techniques and StandardsRajan Jamgekar100% (1)

- CRYPTOGRAPHYDocument23 pagesCRYPTOGRAPHYAnnarathna ANo ratings yet

- UNIT-1: Cryptography & Network Security (3161606)Document75 pagesUNIT-1: Cryptography & Network Security (3161606)Ganesh GhutiyaNo ratings yet

- Cs8792 Cns Unit 1Document35 pagesCs8792 Cns Unit 1Manikandan JNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 AnsDocument39 pagesUnit 1 AnsVikramadityaNo ratings yet

- CS512 - CH03 Testbank Crypto6eDocument6 pagesCS512 - CH03 Testbank Crypto6eRaghad Al-MadiNo ratings yet

- Cryp Tool PresentationDocument115 pagesCryp Tool PresentationAbhishek KunalNo ratings yet

- CS461 09.cryptographyDocument60 pagesCS461 09.cryptographyGodwin Shekwoyiya AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Mod 2 Notes CryptoDocument66 pagesMod 2 Notes CryptoMahalaxmi GinnamNo ratings yet

- CNS New Unit 1Document31 pagesCNS New Unit 1sNo ratings yet

- Cryptography and Network Security Overview & Chapter 1: Fifth Edition by William StallingsDocument85 pagesCryptography and Network Security Overview & Chapter 1: Fifth Edition by William StallingsKazi Mobaidul Islam ShovonNo ratings yet

- 1st Assignment of CSE 403Document8 pages1st Assignment of CSE 403Harjeet SinghNo ratings yet

- 18cse381t - Cryptography Question Bank CseDocument33 pages18cse381t - Cryptography Question Bank CsealgatesgiriNo ratings yet