Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Vesuvius: A Historical Approach To The 1631 Eruption "Cold Data" From The Analysis Ofthree Contemporary Treatises

Uploaded by

centroeedisOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Vesuvius: A Historical Approach To The 1631 Eruption "Cold Data" From The Analysis Ofthree Contemporary Treatises

Uploaded by

centroeedisCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 178 (2008) 347358

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w. e l s ev i e r. c o m / l o c a t e / j vo l g e o r e s

Vesuvius: A historical approach to the 1631 eruption cold data from the analysis of three contemporary treatises

Emanuela Guidoboni

Istituto Nazionale di Geosica e Vulcanologia, Sezione di Bologna, via Donato Creti, 12, 40128 Bologna, Italy

a r t i c l e

i n f o

a b s t r a c t

The 1631 Vesuvius eruption is one of its best known and most studied of its type. However, the historical approach performed within the framework of the Exploris project highlighted new evidence from previously unused or unknown historical sources. These consist of three treatises that were contemporary to the event; although written in Latin, they have been fully translated and analysed. To guarantee systematic use and open access to the large amount of information they contain, they have been provided as a small database. These treatises have provided new information on phenomena that preceded and accompanied the eruption of 1631, making possible the formation of a complex chronological prole, starting from around 6 months before the eruption. The anthropic impact is also outlined. The method applied has produced a chronology of cold data, which are not interpreted from the volcanological standpoint, but only derived directly from the analysed history and sequence of the texts. The analysis of the three treatises has not, however, solved all of the problems connected with the detailed knowledge of the event in 1631. Indeed, problems of two kinds persist: a) linguistic correspondence between the volcanological terms of today and those used in the texts; b) the lack of precision of the measures indicated. Here, the main results obtained from this analysis method are presented, along with a discussion of their limitations and some new perspectives. 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Article history: Received 15 March 2007 Accepted 26 September 2008 Available online 10 October 2008 Keywords: historical volcanology Vesuvius 1631 eruption chronology precursors treatises

1. Introduction On 16 December, 1631, a violent eruption of Vesuvius began, at the end of a long period of repose that had led people to forget the danger of this volcano. As is well known (Rosi et al., 1993; Rolandi et al., 1993; Marturano and Scaramella, 1998), the eruption lasted for several days in its most acute phase, which caused over a thousand deaths as well as major economic damage to the villages of the Vesuvius area. The eruption also left indelible signs on the landscape (e.g. changes in the coastline, the prole of the volcano), and also on the culture of the day, which suddenly felt more vulnerable and weak in confronting this volcanic activity. This eruption ended completely only after a few years, but by January 1632 a number of intellectuals from Naples and other places, were already engaged in drafting reports and treatises to describe and interpret that extraordinary reawakening of Vesuvius. Indeed, between 1632 and 1634, numerous pamphlets, notices, letters and reports were published, along with treatises, some of which were written in Italian, others in Latin, and one in Spanish. This large collection of edited works was already listed in the Vesuvian bibliography of Furchheim (1897), which was variously cited in the scientic works starting from Alfano (1924) and Alfano and Friedlnder (1929), and integrated by Cerbai and Principe (1996). The aim

of the present study was to develop a new critical reading of the apparently known texts, that have been often cited, but not analysed. The volcanological literature of the last 40 years has indeed concentrated more on the treatises and the reports drafted in Italian, sometimes also citing texts in Latin, but without actually consulting them. For this study, three contemporary treaties written in Latin were chosen, which owing to the difculty of the language, have not been adequately taken into consideration previously. 2. The methods and materials of the study: the role of cold historical data The aim of this study was two-fold: i) to attempt to reconstruct the eruption scenario as described by the witnesses in a new way, that has not been analysed previously, to provide new data for volcanologists; ii) to attempt to reconstruct a chronology inferred from these texts, with the separation of the textual and conceptual analyses of the treatises from our present-day scientic knowledge. This method is aimed at providing chronological succession of cold data: this is not intended in the sense of objective data, but in the sense of preinterpreted data from a volcanological point of view. Indeed, I believe that between the historical sources and their volcanological interpretation there is the need for an explanatory,

E-mail address: guidoboni@bo.ingv.it. 0377-0273/$ see front matter 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2008.09.020

348

E. Guidoboni / Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 178 (2008) 347 358

and easily checked, phase, explained from an exclusively critical, philological and historical point of view. In my opinion, this kind of explanatory interface should, on the one hand, favour increased transparency on the part of the volcanologists in the interpretation of historical data; on the other hand, it should make possible more interpretations and uses of the same data, although without necessarily avoiding critical problems relative to the interpretation of words, measures, sequences and durations, for example. In its present state, the volcanological literature of events in the past instead provides an already interpreted version. More like a story of a story rather than scientic use of the historical data, this type of analysis can create a closed circle, in which elements already noted and understood tend to be selected. A small workgroup of exclusively historians and philologists has therefore examined the three texts. The study lasted for over a year. The descriptions of the activity of Vesuvius (and of other volcanoes in the Mediterranean area) in the treatises of the last four centuries are especially rich in detail, and are inserted within a lengthy chronological development. Most of the phenomena described in these treatises can thus be pinpointed in time and in geographical space, and hence be analysed as a fully edged sequence of cold data before any scientic interpretation, as can only result from a historic and philological analysis. The separation of the two levels, i.e. historical and volcanological, which has instead has been followed here, obviously does not come without its surprises, as well as some problems, as it lays bare some unresolved aspects (and also at times some that are hard to resolve), some possible contradictions between the examined texts, or neglected elements that are of primary importance. As compared with the knowledge already gained in the literature, this appears to be a more realistic set of data, although also in some ways more problematic for anyone who has to interpret this data within the volcanological eld. The results presented here constitute a new way of using historical data in volcanology, which was applied for the rst time within the Exploris project. 3. The treatises examined and their cultural context A preliminary analysis of the available choices suggested one of three treatises: Carafa (1632), Mascolo (1634) and Varone (1634). These are only partially known and have been little used by volcanologists as they were written in Latin; the rst two have certainly been cited, while the third has remained virtually unknown. These three treatises are positioned within the Latin language used by the witnesses to the 1631 eruption. The liveliness and the immediacy of the descriptions made by these authors is accompanied by a substantial literary erudition, which was typical of the ecclesiastics and the men of law of those times. The authors were committed to describing and explaining everything they had observed before, during and after the 1631 eruption. This descriptive activity was made, as can be imagined, within the cognitive frameworks of the day, an element that demanded an all but supercial knowledge of the theories as to the origins of volcanoes and earthquakes of those times. In all three treatises, the description of the Vesuvius eruption in 1631 is preceded by dozens of pages of philological, etymological and historical disquisitions (often a discouragement for the volcanologists), which are an example of how the culture of the day addressed these great natural events. The most important element in the explanation of the natural phenomena was still the preponderant role of the tradition of the natural philosophers that had preceded them. So it can be said that there was a knowledge that reiterated itself, with very few variants, thereby forming a compact self-referential system. The knowledge of this context continually interacts with the

description of the events and it is an important background that cannot be ignored by those who analyse the texts. Each of the three treatises has a section concerning the historical activity of Vesuvius prior to 1631. The three authors recall prior eruptions of Vesuvius from very similar sources and literary traditions that are not totally independent, supporting them with their own personal classical culture, and forming some proto-catalogues, which were then at the root of the current catalogues. However, if the eruption of 79 AD was more or less known about from the ancient sources, for the medieval period their data appear to be very scanty. This is also because in the 17th century there was a scarce availability of printed medieval sources, and such texts were mostly manuscripts lying in monastic libraries or in collections of scholars and aristocrats. In the 17th century, many texts of a naturalist type (e.g. essays and treatises in early physics, medicine, astrology), and above all of a theoretical character, were written in Latin. However, Italian was also used for texts in major research: indeed, as is well known, the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems of Galileo was published in Italian, in Florence, in the very same year of 1632 (Galilei, 1632). Then, in October that year the dramatic events of the inquisition trial of Galileo started, an event that was held to be the start of modern science, and understood as research independent of theology. But the parallelism with the three treatises examined is only chronological: indeed, from the standpoint of scientic thought, these three Neapolitan treatises about the 1631 eruption constitute an example of pre-Galilean descriptions of nature, which was then still the exclusive domain of ecclesiastics and theologians, or of medical practitioners and physicists who were still searching for conrmation of ancient natural philosophy. These three texts indeed show how in the widespread knowledge of the day the theories as to the causes of the natural phenomena were practically closed to Aristotelian opinions and theories, which were assumed and elaborated by medieval philosophy, and coded in the Scholastic system. Our three authors ignore the great novelty that the 16th century naturalist thinking had instead articulated, with the doubts cast upon the Aristotelian interpretation of Nature. Mathematical physicists and naturalists, like Georg Bauer, Agricola (14941555), or philosophers like Bernardino Telesio (15091588) and Giordano Bruno (15481600) started an intellectual break-away movement towards a new observation of nature and its phenomena. Our three authors are not the representatives of that restless world of the philosophical researcher, but rather of the closed horizons of intellectual conformism that in those years was typical of church culture. However, when the three are treatises examined, albeit within the limits of the cultural framework and the interests of the authors, they accurately describe the phenomena that had preceded and accompanied the 1631 eruption, and the evolution of the events witnessed directly or reported by a collation of witness reports that they felt could be trusted. The treatise by Mascolo, for example, also contains two famous images of Vesuvius, before and during the 1631 eruption, which in the Europe of the day almost became an icon of that great event (Fig. 1A and B). The three treatises also reveal the devastating effects upon the Vesuvius area and the social responses that arose in the very early phases after the catastrophe. However, for these social and economic aspects there are other numerous coeval documents, more important and authoritative than the treatises, in the ecclesiastic, private and public administration (today in historic archives), that do not fall without the scope of the present study. 4. The authors of the three treatises As indicated above, the authors of these three treatises were typical spokesmen of the Neapolitan intelligentsia in the ecclesiastic and

Fig. 1. Views of Vesuvius A) before and B) after the 1631 eruption, from engravings by Nicolas Perrey, Table 1, included in the treatise by G.B. Mascolo (1634) examined here. These famous images almost became icons of that great event in the Europe of the day.

E. Guidoboni / Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 178 (2008) 347 358

349

350

E. Guidoboni / Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 178 (2008) 347 358

religious spheres. All three were erudite, cultured men, and authoritative rst-hand witnesses of the eruption, as they saw it in person. 4.1. Gregorio Carafa Carlo Marcello (later Gregorio) Carafa was born in Naples in 1588, the son of Marzio Carafa and Faustina, daughter of Fabrizio Sammarco, Baron of Rocca d'Evandro. Carafa undertook a scholastic path that was typical of his elevated social status, and was therefore of high prole. He dedicated himself to the study of theology and philosophy, and joined the Teatini fathers in the house of San Paolo Maggiore of Naples, where he took his vows on 18 November, 1606, taking the name of Gregorio. Still in the house of the Teatini of Naples, he held the Chair of Philosophy for 3 years, and that of theology for six. The fame he acquired among his contemporaries as a theologian, preacher and man of great culture, as well as the position of his family, the support of the Viceroy of Naples, and therefore of the Emperor Philip 4th of Spain, meant that Carafa reached the highest positions in his Order: he was the chief of the Teatini from 1641 to 1643, and the following year he was elected as the 12th general Head of the Order; in 1646 he was reconrmed. He was a rm supporter of ecclesiastical jurisprudence. On 24 August, 1648, he was elected Bishop of Cassano in Calabria; on 23 June, 1664, he became Archbishop of Salerno. He became the extraordinary diplomatic attach of Philip 4th of Spain to Pope Innocence 10th and held several other diplomatic ofces, although perhaps of an exclusively honorary nature. He died in Salerno, on 23 February, 1675. 4.2. Giovanni Battista Mascolo

ii) some of the terms that are commonly used in volcanology today, such as lava, magma and pyroclastic ow, did not have direct equivalents either in the Italian of the times, nor in Latin. The term lava, for example, appears to be used for the rst time only in 1663 (see Cortellazzo and Zolli, 1983, p. 656). Again, in 1779, lava meant a liqueed stone-like substance that is put into

Table 1 Example of a comparison between the current terms and those in Latin from the three treatises examined. Listed here are some technical terms most used today within the volcanological scope and their possible equivalents used in the three treatises examined. For each term the Author of the treatise and the page number is indicated, understood as the rst occurrence of the term in the examined works. Legend: C 1 = Carafa p. 1; M 2 = Mascolo p. 2; V 3 = Varone p. 3 English Volcano Latin and literal meanings mons [mount] mons ignivomus [re-spewing mount] mons ignigenus [re-producing mount] mons igniferus [re-bearing mount] Vulcanius [(mount) of Volcano] vorago [abyss] barathrum [precipice] cavernae [caves] viscera [bowels] os [mouth os ignem evomens [re-spewing mouth] faux [maw] crater [crater] vorago [abyss] hiatus [aperture] hiantis barathri fauces [maw of the wide-open precipice] caminus [chimney] uter [uterus] mugitus [bellowing] fragor [din] sonitus [sound] murmur [rumbling] fremitus [rustling] strepitus [clanging] rumor [noise] terraemotus [earthquake] motus [movement] tremor [tremor] [terrae] concussi [shaking (of the earth)] conagratio [conagration] incendium [blaze] eruptio [eruption] torrentes ignei? [igneous torrents] torrentes ignis? [torrents of re] torrentes ammarum? [torrents of ames] cinis [ash] arena [sand] nube [cloud] nebula [cloud] exhalatio [exhalare] [emission] spiritus [spirit (blowing)] spiritus inammatu [inamed s.] halitus [breath] halitus igneus [igneous breathing] afatus [blowing, breathing] fumus [smoke] exhalationes fumosae; exhalationes fumidae [smoky emissions] fumidi vortices [vortex of smoke] vapo [steam] vapor igneus [igneous steam] torrentes igniti cineris? [torrents of ery ash] torrentes liquati cineris? [torrents of melted ash] uvius cineris [river of ash] uidus cinis [uid ash] pumex [pumice] Source C 4; M 3; V 2 M 155 V 64 V 120 V 64 C 8; M 18; V 119 C9 C 10; M 11 C 11; M 13; V 64 C 8; M 15 C7 C 9; M 219 C 8; M 18; V 29 C 12; M 7; V 123 C 13; M 3; V 82 C9 M3 M 25; V 2 C 10; M 275; V175 C 10; M 275; V361 C 14; M 3; V 118 C 16; M 11 M3 C 89; M 156; V 45 C 15; M 4; V 65 C 9; M 19; V 79 C 10; M 8; V 58 C 11 C 9; M 2; V 119 C 5; M 34; V 3 C 6; M 2; V 2 C 9; M 283; V 4 C 42; M 17; V 253; M 15 M 15 C 6; M 1; V 133 C 28; M 11; V 159 C 12; M 3; V 139 V 159 C 11; M 155; V 63 C 11; M 155; V 63 C 11; M 8; V 63 M 70 C 11; M 12; V 64 M 12; V 64 M 21 C 10; M 3; V 84 C 44; C 87 M 14 C 13; M 21; V 196 M 21; V 196 C 30 C 31 C 31 C 38 C 29; M 219

Vent/bocca

Crater

Conduit

Giovanni Battista Mascolo was born in Naples on 24 June, 1583, and became a Jesuit in 1598. He taught theology and philosophy at the College of his Order, of which he was Rector for some time; subsequently, for 17 years, he held a school of rhetoric at his home. Famous as a good Latinist, he wrote elegant verses in Latin, with a rich and owery style. Pope Urban 8th, who held him in high esteem, made him several career offers, but being of modest and reserved character, Mascolo always refused. His works range across several topics. He died of the plague in Naples on 20 July, 1656. 4.3. Salvatore Varone There is very little information available about Salvatore Varone. He was born in Cinquefrondi (Reggio Calabria) in 1593. He joined the Company of Jesus on 7 October, 1612; he taught grammar, the humanities and rhetoric, and for six years, scholastic theology and morals. He was famed as a very learned intellectual, and two manuscripts in Italian of a rhetorical nature have been attributed to him. In the period of the Vesuvius eruption in 1631, Varone was staying at Portici, and he was thus an eye-witness to the whole eruption. His treatise was written in full maturity, probably using some of his previously unpublished works. He died in Barletta on 5 January, 1648. 5. Textual analysis: from the terms to the meanings One of the most interesting aspects brought to light by this study is perhaps that of the analysis of the terms used in the treatises. The linguistic aspect is relevant to the volcanological interpretation of these treatises, because some misreading may easily be possible, for two main reasons: i) Latin has some false analogies with Italian, the language-medium towards English, and the volcanologists who earlier analysed the literature of the 1631 eruption were mostly Italians;

Rumbling

Earthquake

Eruption

Lava

Magma Ash Cloud Gas Exhalation

Gas/Smoke

Vapour phreatic eruption Piroclastic ow Lahar

Pumice

E. Guidoboni / Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 178 (2008) 347 358

351

movement (una liquefatta lapidea sostanza che messa in movimento, Spallanzani, 1779). According to Cortellazzo and Zolli, the origin of the word lava is Neapolitan, being derived from the Latin labe (to ow), with the main meaning relating to a torrent of rainwater. In Sicilian, a language often used in the past to describe eruptions of Mount Etna, the word lavina refers to stream, and lavinaru to a large torrent canal. The meaning of volcanic ow later prevailed over that of torrent or landslide. Without delving deeper into the etymology and the use of this term, the interpretative problem posed by the three treatises examined is the following: does the fact that the term lava had never been used, nor could it have been by then, mean that the lava of the 1631 eruption did not exist? From the linguistic standpoint, we cannot claim that there was no lava just because it was not specically named as such; instead, the words or the replacement paraphrases must be analysed. In contrast, the more recent stratigraphic dating by Principe et al. (2004) excluded the presence of lava in the 1631 eruption: the authors discuss a variety of evidence in detail (not only paleomagnetic). The different lavas that have been dated to 1631 (Gialanella et al., 1993; Rolandi et al., 1993) have been attributed by Principe et al. (2004) to eruptions of the medieval or post-1631 period. From the historical and linguistic point of view, it may be useful to recall how in the 17th century there was a lack of scientic language

suited to describing the parts of the volcano and its activity with terms that had an univocal meaning, which often makes the recognition of the phenomenological reality that their contemporaries described rather problematic. Sufce it to recall, for example, that to indicate the lavas of Etna erupting in 1669, the mathematician Giovanni Alfonso Borelli (1670), the rst scientist to monitor a volcano and who was a part of the Galilean school, used terms such as: river of re (umen ignitus), torrent of re (torrens ignitus), profusion of re (prouvium ignis), and other similar ones, which we again nd in the three treatises examined. This does not necessarily mean that the rivers of re of Vesuvius in 1631 were lavas such as those of Etna in 1669. However, it is the use of terms that were the same or similar in different volcanological contexts that indicated the need to carry out a very careful and attentive identication of the terms in the current volcanological lexis. Making an intermediate phase explicit to the scientic user, in which the original words are preserved, may perhaps avoid a type of circular thinking between the use of historical data and volcanological interpretations. Perhaps, it would be useful in the rst instance to preserve the original linguistic form, and then only subsequently, through paraphrasing and noting the linguistic context that the authors themselves outline, to identify the present-day equivalent term. We have thus attempted to provide a cold lexis also from the point of view of word meanings, which we have not initially

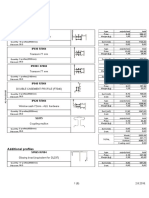

Table 2 Vesuvius, 1631: from the summer to December 16th 4.005.00h UT. Legend. The numbers indicate in succession: month day and hour; the time is approximated to the hour, notwithstanding precise indications by the authors. ex: 1119 22= November, 19th, hours 22 UT. The names of the villages are those currently in use. : indicates missing data. ? = uncertain or dubious date. numbers in italics = day and/or hours contained in the time range indicated in the preceding box, so the phenomena described constitute a specication.m = mount d = day/s h = hour/s. c. = circa Date or chronological range Duration mdh Summer/ 08 ? 09 01 09 10 09 01 12 16 05 10 01 11 30 11 19 22 11 20 07 12 01 ? 11 28 12 02 11 30 ? 12 07 17 12 08 17 12 08 12 08 12 09 12 09 17 12 09 17 17 12 15 [8 d before] 12 15 1m? 11 d 3 m 15 d 2m 9h 5d 5d 1d 1d 8d 7d 6 6 3 2 1 d d d d d4h Time before Source Summary of the description eruption c. 4 m c.3 m 15 d 3 m 15 d 2 m 15 d 27 d c. 18 d ? 18 d c. 16 d ? 10 d 9 9 8 8 7 7 6 3 5 1 d d d d d d d d d d 11 h V C V V V V V V VCM V VCM V V V V V C C V V VCM V M V C Fires visible at night at present-day Erculano (Resina in the texts) eastern slopes of the volcano Lowering of the ground; landslides; ground faulting; smoke emissions; ery emissions (north-eastern slope) Considerable anomalous restlessness among the domestic animals; ight of wild animals from the Vesuvius area Underground noises (from Portici) Rough seas; moderate seismic activity in the coastal region of Vesuvius Emissions, with effects on the herbaceous vegetation [wilting] (Vesuvius area) Darkening and variation in the water chemistry [salinity] (Vesuvius area); collapse of a great overhanging rock (eastern slope); major uplifting of the ground - (slopes, particularly western) Loud noises in the Vesuvius area Moderate seismic activity in the Vesuvius area; underground noises: in the Vesuvius area, and at Herculaneum for some days Underground noises in the western and south-western slopes of Vesuvius Underground noises (Vesuvius area; underground noises (Herculaneum and Vesuvius area) Underground noises and thunder in the Vesuvius area Restlessness among the domestic animals in the Vesuvius area;Small uplifting of the ground; emissions of hot vapours (Vesuvius area) Glowing, ery emissions (from the central crater; at Herculaneum) Tranquillity of the air (Vesuvius area); calm sea (sea facing the Vesuvius area) Moderate seismic activity (Vesuvius area) Darkening of the waters of the wells (Vesuvius area) Tranquillity of the air in the area of Vesuvius and in Naples Tranquillity of the air and restlessness of the animals in the Vesuvius area, calm sea in the coastal area of Vesuvius Calm sea (coastal area) Repeated seismic activity felt at Naples and in the Vesuvius area, for a range of c. 7.380 km Restlessness among the domestic animals (Vesuvius area, from Portici); moderate and repeated seismic activity (30 shocks); underground noises Vesuvius area Intense and repeated seismic activity in the area of Vesuvius and Naples Underground noises and seismic activity Vesuvius area Seismic activity; opening of faults and landslides; landslides between the Atria and the summit of the Veolo, just above the path that goes from Atria and circles the Veolo, in the middle of the mountain's slopes, closer to the one facing Atria Very loud underground noises in the Vesuvius area, ebbing of the sea in the Gulf of Naples, between Pozzuoli and the coast facing the mouth of the River Sarno; earthquakes, landslides, ground faulting; loud underground noises in the Atria; intense smoke emissions; ery emissions; rock expulsion (from the central crater, on the eastern slope, seawards) Fiery emissions; thunder, underground noises and lightening, rock expulsion, ash and smog, emission of a cloud (Vesuvius area), violent seismic activity Smoke emissions; loud underground noises; ground faulting; opening of a large chasm; cloud emission reaching about 37 km in height; haze (from the fracture appearing in the Atria)

12 10 12 15 12 10 12 15 21 12 11 17 12 13 17 12 13 12 16 12 13 12 15 20 12 14 17 12 15 21 12 15 20 12 16 01 12 15 20 12 16 04 12 15 20 12 16 05 12 15 20 12 16 07 12 15 21 12 16 04

5h 8h 8h 2d 7h ?

8h 8h 8h 8h 7h c. 1 h

12 16 04 12 16 05

c. 1 h

c. 1 h

12 16 04 12 16 05 12 16 05

c. 1 h ERUPTION

c. 1 h

VCM V

352

E. Guidoboni / Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 178 (2008) 347 358

Table 3 Vesuvius activity: from 1631, December 16, h. 05 to December 18. See legend in Table 2 Date chronological Duration Source range Mdh 12 16 12 18 2d V C M C C C V VM Hurling of rocks and lapillus; obstructions of the waterways and subsequent overowing; eruptions of re from the central crater, across a range of c. 9.225 km, with particular intensity on the northern slope, as far as Puglia Fiery gas emissions, underground noises and lightning, ash and dust, emission of a cloud, violent seismic activity and opening of a new eruptive mouth (from the crevasse that opened in the Atria) Seismic activity; underground noises; thunder; ery emission; cloud (Vesuvius area). Strong underground noises (Vesuvius area) Less frequent and less intense underground noises (Vesuvius area) Lowering of the ground owing to the collapse of the wall: Mount Veolo (central crater) lowered by about 450 m. Moderate and unceasing seismic activity in Campania; rocks hurled at Torre del Greco (Herculaneum), eruptions of re at Boscoreale (Boschi) Smoke emissions; strong underground noises; cracking of the ground; opening of a new eruptive mouth (western side of the crater); emission of a cloud that reaches around 37 km in height; darkness from the ssure opening in the Atria Cloud; suspension of ash and dust; smog; warm and sulphurous emissions (Vesuvius area) Smog; raining ash; cloud; thunder; lightening; re emissions; raining sand and ash; hurling of ery rocks; sulphurous emissions Moderate seismic activity (Vesuvius area; Naples) Lightning and thunder coming from a cloud of the crater?4; seismic activity; underground noises (Portici, Villa Nava, Torre del Greco, Ercolano) raining ash; dust suspension; darkness (Portici, Villa Nava, Torre del Greco, Herculaneum) Withdrawal of the sea between the coast of Campania and the Island of Capri (beach near Serino); ery waters in the coastal zone of Amal; territory around Serino; Ottaviano. Loud underground noises, emission of a cloud from the crater; hurling of rocks, lightning, emission of re from the ssure that opened in the Atria Raining ash in Campania, Puglia, Basilicata, and regions that face the eastern coast of the Adriatic and on the northern coast of the Aegean, as far as the current Strait of the Dardanelles; darkness; sulphurous emissions, dust suspension (Campania region) Moderate seismic activity; underground noises; cloud; darkness(in Naples) Falling ashes Rough seas in the Gulf of Naples, between Naples and the coast overlooking the cliff of Rovigliano/mouth of the Sarno [the stretch of the coast affected by the phenomenon is about 16 km long] Eruption of volcanic material; hurling of ery masses from the central crater in the direction of Ottaviano Warm emissions; strong underground noises; hurling of rocks; intense seismic activity: collapse of the wall of the central crater; ssure opening in the Atria, central crater and zone lying between the two craters Raining ash, hurling rocks and pomice stones from the ssure opening in the Atria as far as northern Puglia (Apulia Daunia); Arpaia (CE), eastern slope, in the direction of the city of Nola, Ariano Irpino (AV), Avellino Raining ash; hurling rocks and pumices from the ssure that opened in the Atria, eastern slope, in the direction of Nola, Ariano Irpino, Avellino Underground noises felt at a great distance Clouds of smoke; raining ash; sulphurous emissions; hurling rocks The rain of ash and rocks fell violently upon Nola, Palma Campania, Trocchia - Pollena and Ottaviano. The rst of these cities, in particular, was repeatedly hit by rocks hurled from the volcano. The rock fall-out above all affected the north-eastern side. The cities furthest away are Nola and Palma Campania, (at about 12 km from the crater) Seismic activity (Vesuvius area); raining ash and rocks from the central crater; particularly upon; eruption of re from the central crater, above all upon Torre del Greco (Herculaneum) and Torre Annunziata (Pompeii), as far as the sea Intense and continuing seismic activity in the Vesuvius area Increase in the eruptive activity; darkness (northern side of the volcano; Ottaviano, Palma Campania, Lauro, Trocchia-Pollena, Somma Vesuviana) Intense seismic activity felt at Naples Raining ash; increase in the seismic activity (Vesuvius area; Naples) Fiery vapour? (Torre Annunziata) re in the woodland area at Herculaneum Raining ash and earth at a great distance5, darkness in the Vesuvius area Unidentied luminous phenomenon Moderate seismic activity in the area of Vesuvius and Naples Darkness; cloud; lightning; underground noises (Vesuvius area); rough seas along the coast overlooking the Vesuvius area Darkness; sulphurous emissions; dust particle suspensions described in Naples); smog, raining ash (Vesuvius area; Naples) outow of ashes, darkness; lightning (Vesuvius area) Withdrawal of the sea and subsequent return wave in the sea facing the Vesuvius area, for c. 370.8 m Withdrawal of the sea facing Portici, Resina, Pompeii and Herculaneum (ancient site) for about 55.35 m from the coast, and the return of the water was not wholly complete Facing Castellammare di Stabia, Granatello for about 5070 m; length c. 550 m. At Torre del Greco, length c. 370 m; width c. 75 m. At Torre Annunziata length c. 180 m, c. 35 m Loud underground noises, intense and repeated seismic activity Abundant rainfall (Naples) Obstruction of the waterways and subsequent ooding that affected the following towns and areas: Pollena, Trocchia, Massa di Somma, the plain of Palma Campania, Lauro and its neighbourhoods, Nola, and the villages, Marigliano and Cicciano, Arienzio and Casalnuovo di Naples; south-eastern side, in particular along the bed of river Sarno, in the direction of Torre Annunziata; obstruction of the water pipes (pipes from Limatola to Maddaloni and Arienzo; north-western side and underlying soil, in the direction of Arienzo and Maddaloni) Underground noises (Vesuvius area) Underground noises, eruption of re from the central ssure of the Atria at Torre del Greco (some homes burned down and the church of the Carmelitani), direction Massa di Somma and San Giorgio a Cremano; raining ash, hurling of rocks6, strong seismic activity at Torre Annunziata Eruption of re; hurling of rocks; raining ash; obstruction of the waterways and subsequent ooding7; perhaps obstruction of the aqueducts in the south-eastern side, in particular along the bed of the River Sarno, in the direction of Torre Annunziata; north-western side, and underlying soil, in the direction of Arienzo (Argentia) and Maddaloni (Mataluni) Summary of the description

12 16 05 12 16 ?

12 16 05 12 16 07 12 16 05 12 22 12 16 05 12 18 12 16 05 12 18 12 16 05

2 7 2 2 ?

h d d d

12 16 05 12 16 08 12 16 07 12 17 05 12 16 07 12 17 12 16 08

3h 22 h 1d ?

V M VM V V

12 16 08 12 16 12 4 h

12 16 10 12 16 11 1 h 12 16 10 12 16 12 2 h 12 16 10 12 16 15 c. 6 h 12 16 12 ? 12 16 12 12 16 13 12 16 13 12 17 ? ? 2d

V C V V C V C VM V V

12 16 04 12 17 c. 1 d 12 16 04 12 17 1 d 12 16 15 12 16 ?

12 17 11:30 12 17 30' min 12 12 16 16 12 16 18 2 h 12 16 17 12 16 18 1 h 12 16 17 12 16 18 12 16 17 12 16 22 12 16 19 12 16 22 12 16 19 12 17 05 12 16 20 12 17 10 12 16 20 12 17 05 12 16 20 12 17 05 12 17 0512 17 08 1h 5h 3h 10 h 8h 9h 9h 3h

M V V C M V C VC C V VC C V

12 17 05 12 17 13 8 h 12 17 08 12 17 09 1 h 12 17 09 12 17 ?

C VM VCM

12 17 09 12 17 11 2 h 12 17 09 12 17 24 h 11-13 12 17 09 12 17 15 6 h

C C

E. Guidoboni / Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 178 (2008) 347 358 Table 3 (continued) Date chronological Duration Source range Mdh 12 17 09 12 17 11 2 h 12 17 10 ? VCM Summary of the description

353

12 17 10 12 17 12 2 h

12 17 10 12 17 10 12 31 12 17 09 12 17 11 12 17 09 12 17 11 12 17 10 12 17 13 12 17 10 12 28 12 17 10 01 14 12 17 13 12 17 15 12 17 17 12 17 21 12 17 12 18 12 17 20 12 18 05 12 7 20 12 18 05 12 18 05 12 18 07 12 18 06 12 18 08 12 18 06 12 18 13 12 18 17 12 19 17

? 15 d 2h 2h 3h 11 d 28 d 2h 4h 1d 9h 9h 2h 2h 7h 1d

Variations in the coastline, with the uprising of new wharves in the sea, created by the material transported by the ery river (Gulf of Naples, from the port of Naples to Castellammare di Stabia; sea facing Granatello, Torre del Greco and Torre Annunziata V Sudden stillness of the air and the sea at Naples and in the sea ahead Underground noises accompanied by hurling lapilli and followed by the emission of seven rivers of re coming from the central crater V 1st river of ery ash in the direction of Naples, passing along the bed of the Sebeto, the territories of Barra and San Giorgio a Cremano, the surroundings of Villa Nava, as far as owing into the sea, near the sanctuary of Santa Maria del Soccorso partially 2nd river of ery ash towards Portici and as far as the sea; variation in the coastline. From the central crater, deviating after 0.922 km, CM with a front of c. 0.553 km 3rd river of ery ash, deviates after 1.107 km, heading towards Ercolano, as far as the sea, with a front of at least c. 1.845 km 4th river of ery ash, from the central crater, deviating after c. 0.11 km, directing towards Torre del Greco, with a front of c. 5.535 km 5th river of re across the territory between Torre del Greco and Torre Annunziata, as far as the sea, with a front of c. 1.845 m 6th river of re in the direction of Torre Annunziata and Boscoreale as far as the sea 7th river of re, ash and ery bitumen in the direction of Ottaviano, PollenaTrocchia, Santa Anastasia, Massa di Somma and the small inhabited centres in the surrounding areas; suspension of ash and dust in the air V Underground noises, accompanied by hurling lapilli and followed by the emission of seven rivers of re (from the crater) V Repeated seismic activity C Raining ash; hurling rocks C Strong seismic activity (Torre Annunziata) raining ash as fare as the port of Vaissetun? V Sudden drying up of the waters in a basin in the territory of Ottaviano V Fire in the sea facing Portici V Repeated seismic activity in Naples C Cloud, seen from Naples V Fiery glows, seen from Naples V Obstruction of the waterways and subsequent ooding of the territory of Arienzo, Nola, Arpaio and Cicciano CM Seismic activity felt in the Vesuvius area felt and Naples; ery emissions; rocks hurled from the central crater M Boiling over of the waters of the sea in the coastal zone of the Vesuvius V Diminution in the eruptive activity C Cloud from the central crater C End of the ery emissions coming from ssure opening in the Atria; emissions from the central crater M Cloud, seismic activity, underground noises in the Vesuvius area and Naples

interpreted. Table 1, for instance, shows the complexity of these linguistic transfers and the variety and overlap of terms that were used to indicate words that today have a precise and unequivocal meaning. 6. The heart of the results: a chronology of the great eruption with individual memories compared On the grounds of the synoptic comparison of the three treatises, a chronology of cold data was prepared, in the previously dened sense. Tables 2, 3 and 4 provide the heart of the results. This operation has required the formation of a small database, which has allowed us to select the various phenomena described and arrange them according to various indicators, among which there is their occurrence in time. The time indications are provided by the treatises as canonical hours (i.e. from daybreak to sunset) or as hours all'italiana (i.e. from sunset to sunset): together, these local uses were transformed into the single time system of today (universal time). The hours are obviously approximate owing to a lack of recording of less than a half hour. In the three treatises, the phenomena that occurred are narrated in a way that is in accordance with the purposes of the narrator, and because of this, the phenomena observed are often not described in chronological order. The three authors, and in particular Varone (1634), often introduce fragments of personal memories to explain or contextualise some of the events, or to reinforce their theoretical links with ancient tradition: for this reason the narrative is discontinuous and is performed at different levels. The measures adopted by the authors to quantify various aspects of the reality that they describe also require some clarication. The problem is not so much the conversion of the ancient measures (into pertiche, passi, tumoli, miglia napoletane ecc) into the current metric ones, but rather to understand if these measures can be trusted. The impression one has is that some of the measures used are

exaggerated, not only because they were inuenced by the emotions surrounding the event, but also mainly because the forma mentis of precision was not widespread at the time. For example, the height of the pine-tree shaped cloud that rose into the sky from Vesuvius on 16 December, 1631, was indicated by Varone as equivalent to circa 37 km (but is instead considered to be circa 15 km by Rosi et al. (1993). Instead, the distances between the various locations, the paths of the rivers and the rivers of re, and the burnt surfaces almost always appear to be congruent. For the analysis of these rivers of materials erupting from Vesuvius that are described in the three treatises, it is necessary to note that this section is a rather complex one that has not yet been adequately analysed. For example, Varone listed seven rivers, while Carafa and Mascolo were less precise. A more direct comparison between the three authors will indeed be interesting to have a precise picture of the erupted materials at last and to provide a critical understanding of the relationships between these texts and the use that has been made of them by volcanologists in the literature. In this regard, Varone, who appears to be wholly independent from the other two authors, provides highly detailed chronological and topographical particulars, along with a description of the materials which the rivers consisted of. The descent of the seven rivers, which is summarised in Table 3, is an important part of the treatises; the treatise of Varone contains many details. From Varone, we can appreciate that there were seven rivers that were different in their directions and in the materials of which they were composed (at least as they were perceived through the eyes of a witness of the time). The rst river was described as being of ery ash, and as heading in the direction of Naples (see Table 3 for the routes); also the second river was of ery ash and in heading towards Portici it reached the sea, causing a variation in the coastline; this river arose from the main crater and it deviated after 0.922 km; its front was of circa 0.553 km. The third river, which was also of ery ash, deviated after 1.107 km, heading towards Ercolano, as far as the sea, with a front

354

E. Guidoboni / Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 178 (2008) 347 358

Table 4 Vesuvius activity: from midday on 18th December 1631 to 31st December 1632 see legend in the Table 2 Date/Chronological range 1631, 12 18 12 20 12 18 12 24 12 18 12 25 12 18 12 31 12 18 12 31 12 18 17 12 19 17 12 19 05 12 20 07 12 19 17 12 20 17 12 19 17 12 21 17 12 20 17 12 21 17 12 21 17 12 22 17 12 22 17 12 24 17 12 23 17 12 24 17 12 24 11 12 24 17 12 25 17 12 24 12 31 12 25 17 12 26 17 12 29 05 12 29 08 12 30 05 12 30 08 12 30 22 12 31 07 12 31 06 18 12 31 06 18 12 31 06 24 12 31 17 01 01 17 12 31 17 01 01 07 1632 01 01 01 14 01 01 20 01 02 17 01 01 17 01 02 17 01 02 03 12 01 05 17 01 06 17 01 06 22 01 07 07 01 06 02 23 00 01 07 07 01 09 05 01 09 12 01 15 17 01 16 17 01 30 17 01 31 17 02 04 17 02 05 17 02 12 17 02 13 17 02 16 02 16 03 12 02 18 17 02 19 17 02 19 17 02 20 17 02 20 17 03 01 17 02 23 17 03 01 03 12 03 02 17 03 03 17 03 11 17 03 12 17 03 13 22 03 14 07 03 21 17 03 22 17 04 01 04 20 04 18 17 04 19 17 05 19 17- 05 20 17 05 31 22 06 01 05 06 11 06 22 04 06 22 05 06 22 15 06 22 17 06 22 17 06 22 22 07 09 05 07 09 08 07 31 03 07 31 06 08 13 22 08 14 05 08 13 17 08 14 17 09 11 09 01 09 30 09 16 17 19 17 17 09 25 18 09 25 20 09 27 17 09 28 17 10 26 05 10 27 20 Duration 2d 6d 7d 13 d 13 d 1d 1d 1d 2d 1d 1d 2d 1d ? 1d 7d 1d 3h 3h 9h c. 5 m c. 5 m c. 6 m 1d 14 h 14 d 21 h 1d 2m 1d 9 1 ? 7 1 1 1 h m 18 d h d d d Source V V V V CM M M V C M M V M V M M M V V M M M V CM V V M V M CM C V M M M M M V V V M M C C M V M M C M VC M M M M C M M CM M C M M M M M M M M M M Summary of the description Collapse of part of the wall of the crater of Vesuvius; underground noises; seismic activity (also felt in Naples) Rocks hurled from the crater, onto the slopes; smoke emissions; warm emissions; thunderclaps (from the crater, Vesuvius area) Moderate and continuing seismic activity (in Naples) Moderate and repeated seismic activity, with at least 60 shocks (in Naples) rocks hurled (from the crater, on the slopes) underground noises (Vesuvius area, Naples) Moderate and repeated seismic activity, with at least 60 shocks (in Naples) Cloud Storm (Vesuvius area; Naples) Underground noises; rocks hurled; ery emissions from the central crater Fiery emissions; seismic activity, cloud (from the crater; visible in Naples) seismic activity (Vesuvius area; Naples) Violent storm (Vesuvius area Naples) Underground noises; seismic activity (in Naples); Darkness, suspension of ash and dust (Vesuvius area; in particular in Nola) Underground noises; seismic activities (in Naples) Flooding (Nola and outlying territories) Darkness(Vesuvius area) Rain of ash (Vesuvius area) Smoke emission (Vesuvius area) Falling of ery rocks? (the Church of Santa Maria di Pugliano was hit) Storm; underground noises; hurling of ery rocks; ash from the main crater, in the direction of Marano and the sea Intense seismic activity (Naples) Storms; eruption of water and re (Vesuvius area, above all in the vicinity of Herculaneum and Ottaviano) Moderate and repeated seismic activity, with at least 60 shocks (in Naples) rocks hurled (from the crater, on the slopes) underground noises (Vesuvius area, Naples) Moderate and repeated seismic activity, with at least 60 shocks (in Naples) Smoke emission (Vesuvius area) Underground noises; seismic activity (in Naples) Sulphurous emissions in Naples Repeated seismic activity Seismic activity, sulphurous emissions (Vesuvius area, Naples) Raining ash (Naples) Emissions of smoke (from the central crater), smoke emissions (sea facing Torre Annunziata) Underground noises; seismic activity (in Naples) Sulphurous and bituminous emissions (?) (Vesuvius area; Naples) Seismic activity (Vesuvius area; Naples) Fiery emissions; seismic activity (Vesuvius area; Naples) Falling of ery rocks (the Ospizio della Quercia was hit) Fiery emissions; dense smoke emissions; darkness (Vesuvius area; Naples) Seismic activity (in Naples) Smoke emissions; ery emissions (from the central crater; in Naples) Smoke emissions; ery emissions (from the central crater; in Naples) Seismic activity; ery and bituminous emissions (Vesuvius area; ooding due to the heavy precipitations (Mount Abella) Two strong shocks felt in the Vesuvius area and in Naples; eruption of incandescent ash from the crater Emissions of smoke and darkness, underground noises, sulphurous emissions (central crater) Progressive enlargement of the mouth of the crater, smoke emissions, sulphurous emissions, ery emissions (central crater); ssure opening in the Atria; moderate and continuing seismic activity (in Naples) underground noises, darkness (Vesuvius area) Underground noises; sulphurous and bituminous emissions (?); seismic activity (Vesuvius area) Underground noises; moderate seismic activity; sulphurous emissions; darkness(in Nola) Fiery emissions (Vesuvius area) Raining ash (Vesuvius area, Naples) Fiery emissions from the central crater Heavy rain; rocks from the volcano's crater; sulphurous emissions (Vesuvius area) Underground noises; smoke emissions (from the central crater; in Naples) Seismic activity; hurling of incandescent rocks (from the crater; Vesuvius area) Seismic activity (two shocks); ery and sulphurous emissions (Vesuvius area) Emissions of smoke from the sea; boiling over of the waters (coast of the Gulf of Naples, roughly from Naples to Castellammare di Stabia) Raining ash; underground noises (from the crater, as far as Naples) Underground noises (Vesuvius area)water eruption (slopes of the Vesuvius) Seismic activity (Vesuvius area) Seismic activity; sulphurous emissions (Vesuvius area; Naples) Strong seismic activity; underground noises (Naples) smoke emissions (from Naples) Moderate seismic activity (Naples) Smoke emissions Moderate seismic activity (Naples) Seismic activity (Naples) Seismic activity (Naples) Intense atmospheric precipitations (Campania region) Intense atmospheric precipitations (Vesuvius area) Repeated seismic activity of moderate intensity (Naples) Seismic activity (Naples) Seismic activity (Naples) Sulphurous emissions (from the crater; in Naples) Dense smoke emissions (from the crater)

1d ? 24 d 1d 1d 9d ? 11 d 1d 1d 9h 1d 19 d 1d 1d 1d c. 5 m 1h 2h 5h 3h 3h 7h 1d c. 2 m 29 d 1d 2h 1d c. 2 d

E. Guidoboni / Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 178 (2008) 347 358 Table 4 (continued) Date/Chronological range 1631, 12 18 12 20 11 09 06 11 09 08 11 28 17 11 29 17 11 19 05 11 19 07 12 02 05 12 02 08 12 08 05 - 12 08 08 12 08 22 12 09 07 12 15 22 12 16 17 12 18 12 20 Duration 2d 3h 1d 2h 3h 3h 9h 19 h 2d Source V M M M M M M M V Summary of the description Collapse of part of the wall of the crater of Vesuvius; underground noises; seismic activity (also felt in Naples) Moderate seismic activity (Naples) Darkness Seismic activity; dense smoke emissions (from the crater; in Naples) Moderate seismic activity (Naples and neighbouring territories) Seismic activity (Naples) Seismic activity (Naples) Heavy atmospheric precipitations; underground noises (?); seismic activity; sulphurous emissions (Vesuvius area, Naples) Collapse of part of the crater wall, underground noises, seismic activity

355

of at least circa 1.845 km. The fourth river was also described as being of ery ash that arose from the central crater, and it deviated after circa 0.11 km, heading towards Torre del Greco, with a front of circa 5.535 km. The fth and sixth rivers were instead described only as being of re; the fth crossed the territory between Torre del Greco and Torre Annunziata, as far as the sea, with a front of circa 1.845 km, and the sixth river headed in the direction of Torre Annunziata and Boscoreale, as far as the sea. Finally, the seventh river was formed of ash and ery bitumen, and it descended in the direction of Ottaviano and Massa di Somma. Fig. 2 shows an image, which was not a part of the treatises, but instead drawn by a contemporary, of some of the seven rivers that poured from the central crater, some of which reached the sea. Despite its limitations, the chronological reconstruction of the events has the purpose of providing the order, of correlating and integrating the observations of the various authors, as we follow the unfolding of the events. The earthquakes mentioned have been selected, recomposing the picture of the perceived seismicity, which is obviously less than the real one (which today can be obtained from instrumental detectors), which will have been well below the sensitivity of human perception. In Fig. 3 the landslips and landslides on Vesuvius are indicated; these might have been deformations that preceded the eruption, and the

various shocks before and after the eruption, from October 1631 to January 1632, according our three authors. Fig. 4 represents the felt seismicity from February 1632 to September 1633, as described in the three treatises. For this aspect, it can be seen that most of the events mentioned are of an intensity between III and IV degrees on the MCS; then there are periods of slight and incessant activity, which remain as an overall indication. There are also two events of more sustained intensity (VII MCS), that occurred soon after the eruption, on 17 December and 18 December, 1631, in Torre Annunziata (described by Carafa). The overall trend of the seismicity justies the state of alarm, panic and prostration that the population of the Vesuvius area underwent in the space of at least 3 months, even of only because of the continuing seismic activity: an element that today is not secondary with a view to information and prevention. From summer 1631 to 16 December, 1631, at 4.005.00 h UT (i.e. until the beginning of the explosive phase of the eruption), a countdown was also calculated, to give an immediate idea of the type of phenomena that we can today term as precursors. Some ideas as to how the contemporary people saw and experienced this eruption is also contained in the iconography of the times, which set the memory of particular aspects of that event. The availability of images of this eruption, as is known, is very

Fig. 2. Some of the seven rivers of re described in the treatises examined here, seen as a print by J. Passari (Bibliotque Nationale de France, Estampes et Photographies, VX46).

356

E. Guidoboni / Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 178 (2008) 347 358

Fig. 3. The Vesuvius area. Some of the phenomena reported in the examined treatises are indicated here, which occurred from September 1631 to January 1632: probable deformations, which are not specically detailed in the treatises, but are described as some visible effects, such as small landslides or landslips, on Vesuvius. Variations in the water chemistry, noise and seismicity are also indicated.

extensive. Here I have chosen some of the lesser known images that give a particular idea of the phenomenon and that in a certain sense also explain the chronological data (see Table 2). As regard to the social aspects and the anthropomorphic impact, the sources of the time are very many and very rich. To limit ourselves here to an immediate and synthetic suggestion, we can see Figs. 5 and 6: the former shows an image of the disaster as seen by the witnesses who saw the eruption from Naples: a dense and very dark cloud enveloped the Vesuvius area and the city itself, and Vesuvius was almost concealed behind an enormous mass of smoke and ash. In the latter Fig. (Fig. 6) the volcano is almost of secondary concern, with emphasis on the social unrest and the population movement that the event triggered: it was a true and proper exodus from the country villages towards Naples, an event of social unrest that the author placed in the foreground as

compared with the natural phenomenon. This image immediately conveys the implications of an eruptive event which, if it occurred today, would have far more devastating impacts in the current demographic and economic scale of the area (over 700,000 people). 7. Discussion and conclusions The analysis performed on the treatises of G.B. Mascolo, G. Carafa and S. Varone can be considered as the initial phases of a study and analysis that should include other Latin treatises and the ones written in Italian and Spanish, as well as other types of sources (administrative and scal). This rst analysis has made available a volcanological interpretation of a broad chronology and description of the phenomena that preceeded, accompanied and followed the 1631 violent

Fig. 4. The Vesuvius area. Perceptions and mentions of earthquakes are shown from the three treatises examined, from February 1632 to September 1633.

E. Guidoboni / Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 178 (2008) 347 358

357

Fig. 5. The great cloud and black smoke that enshrouded Vesuvius during the eruption on 16 December, 1631, as seen in a particular from a painting of Rocco Spataro, an eye-witness of this event (Naples, private collection).

eruption phase. Among the precursor phenomena, some new ones have also emerged that were previously unknown in the literature, and that are better analysed and interpreted in Bertagnini et al. (2006) on the base of the three treatises (Guidoboni, 2004). The analysis of the Latin terms used to describe the phenomenology of the eruption in the three treatises has paved the way to a series of considerations that can be summarised: i) there is no direct relationship between the terms in the treatises and the current volcanological lexis; ii) it has been possible to build a chronology of cold data from the treatises (as it would have been for other contemporary texts), with a signicance not of objective data as would maybe be equivalent to instrumental data but of data interpreted only from a historical and philological point of view; iii) the interpretative phase of the volcanologists should follow from the cold data and be performed in a transparent manner. The method of analysis applied in this study has shown, in my opinion, that it is possible to avoid apparent conicts in data in the phase of scientic interpretation. This aspect is strongly multidisciplinary: bearing this in mind avoids the risk of circular thinking, which can easily take shape between opinions (or hypotheses, or data) of the volcanologists and historical testimonies (see the problem of the presence or absence of lavas discussed above). An exact picture of the occurrence of the great 1631 eruption of Vesuvius presents some elements that are also relevant with a view to civil protection, such as the type of precursor phenomena perceived by the witnesses and the time that elapsed before the acute phase of the eruption. With a view to prevention, other interesting aspects include the extent of the area where the ashes fell, the overall human impact, the number of dead (which uctuates between 300 and 1000; far fewer than the gure reported in the literature), and the intense migratory ow towards the city of Naples that was triggered by the

eruption. To evaluate the last of these, we have made use of the historical demographic data available in the literature. As a whole, the analysis performed has allowed us to locate 126 villages or isolated buildings that underwent effects of various kinds due to this eruption (e.g. ashes, ery masses, water, mud) and the detailed picture should in any case be eventually better studied. For the social aspects and the economic impact in the villages of the Vesuvius area, there are, of course, many other types of sources of information that are more specic than these treatises, such as the administrative and scal records, the correspondence between the central power and the local administrations, and the feudal administrations (preserved in the State Archives and by the present-day Councils). Furthermore, the topography of Vesuvius and its changes following this eruption can now undergo further assessment through scanning the database for such manifestations and subjecting them to validation in the eld. Acknowledgements The textual analysis and critique of the treatises was carried out with a working group comprising a researcher from SGA Storia Geosica Ambiente, funded by the Exploris project in 20022003. We would like to thank the following for their participation in this study and analysis: Federico Sant'Angelo and Federica Foschi for the translations from Latin; Gaia Fanelli and Maria Giovanna Bianchi for the selection of the texts for the database; Dante Mariotti for the localisation and the geo-referencing of the cited toponyms and the volcanic effects. References

Alfano, G.B., 1924. Le eruzioni del Vesuvio tra il 79 e il 1631 (studio bibliograco). Scuola Tipograca Ponticia, Valle di Pompei, 58 pp. Alfano, G.B., Friedlnder, I., 1929. La storia del Vesuvio illustrata dai documenti coevi. Karl Hohn, Ulm, 69 pp., 107 plates.

358

E. Guidoboni / Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 178 (2008) 347 358

Fig. 6. The eruption of Vesuvius in 1631: the social unrest and the population movements that the event triggered off. Painting by Scipione Compagno (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum).

Bertagnini, A., Cioni, R., Guidoboni, E., Rosi, M., Neri, A., Boschi, E., 2006. Eruption early warning at Vesuvius: the A.D. 1631 lesson. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L18317. doi:10.1029/2006GL027297. Borelli, Giovanni Alfonso, 1670. Historia, et meteorologia incendii Aetnaei anni 1669, Regio Julio (Reggio Calabria), 176 pp.; reprinted. In: Morello, N. (Ed.), Storia e meteorologia dell'eruzione dell'Etna del 1669 (Biblioteca della Scienza Italiana). Giunti, Florence, 271 pp. Carafa, Gregorio, 1632. In opusculum de novissima Vesuvij conagratione, epistola isagogica, second ed. Egidio Longo, Naples. 95 pp. Cerbai, I., Principe, C., 1996. BIBV, Bibliography of Historic Activity on Italian Volcanoes. Istituto di Geocronologia e Geochimica Isotopica CNR Pisa IGGI Internal Report no. 6/96. 687 pp. Cortellazzo, M., Zolli, P., 1983. Dizionario etimologico della lingua italiana. vol. 3 (I-N). Zanichelli, Bologna, pp. 538815. Furchheim, F., 1897. Bibliograa del Vesuvio, compilata e corredata di note critiche estratte dai pi autorevoli scrittori vesuviani. F. Furchheim di E. Prass, Naples, xii+. 299 pp. Galilei, Galileo., 1632. Dialogue concerning the two chief world systems - Ptolemaic and Copernican, translated by Stillman Drake; foreword by Albert Einstein. Berkeley London, University of California Press, 1953, 524 pp.; 1967, xxvii+505 pp. Gialanella, P.R., Incoronato, A., Russo, F., Nigro, G., 1993. Magnetic stratigraphy of Vesuvius products. I. 1631 lavas. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 58, 211215. Guidoboni, E., 2004. Analysis of three coeval Treatises on the 1631 Vesuvius eruption, nalised to the evidence of the precursors: Gregorio Carafa, Giovan Battista

Mascolo, Salvatore Varonius, Internal Report, D2.4 of the EU Project: Explosive eruption risk and decision support for EU population threatened by volcanoes, EXPLORIS, Contract no. CT-EVR1-2002-40026, Coordinator Neri, A., INGV. Marturano, A., Scaramella, P., 1998. The role of primary sources in reconstructing the history of volcanoes: the eruption of Vesuvius in 1631. In: Morello, N. (Ed.), Volcanoes and History. Brigati, Genova, pp. 281299. Mascolo, Giovan Battista, 1634. De incendio Vesuvii excitato xvij. Kal. Ianuar. anno trigesimo primo sculi Decimiseptimi libri X. Cum Chronologia superiorum incendiorum; et Ephemeride ultimi. Secondino Roncagliolo, Naples, 350pp. Principe, C., Tanguy, J.C., Arrighi, S., Paiotti, A., Le Goff, M., Zoppi, U., 2004. Chronology of the Vesuvius activity from A.D. 79 to 1631 based on archaeomagnetism of lavas and historical sources. Bull. Volcanol. 66, 703724. Rolandi, G., Barrella, A.M., Borrelli, A., 1993. The 1631 eruption of Vesuvius. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 58, 183201. Rosi, M., Principe, C., Vecci, R., 1993. The 1631 eruption of Vesuvius reconstructed from the review of chronicles and study of deposits. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 58, 151182. Spallanzani, L., 1779. Viaggi alle Due Sicilie e in alcune parti dell'Appennino dell'abate Lazzaro Spallanzani, 6 vols. Turin. Varone, Salvatore, 1634. Vesuviani incendii historiae libri tres. Francesco Savio, 409 pp.

You might also like

- DeJong Ellis, M. 1983. Correlation of Archaeological and Written Evidence For The Study of Ian Institutions and ChronologyDocument12 pagesDeJong Ellis, M. 1983. Correlation of Archaeological and Written Evidence For The Study of Ian Institutions and Chronologyhera3651No ratings yet

- Third Thoughts: The Universe We Still Don’t KnowFrom EverandThird Thoughts: The Universe We Still Don’t KnowRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (5)

- Theories of the World from Antiquity to the Copernican Revolution: Second Revised EditionFrom EverandTheories of the World from Antiquity to the Copernican Revolution: Second Revised EditionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (9)

- The Abyss of Time: Unraveling the Mystery of the Earth's AgeFrom EverandThe Abyss of Time: Unraveling the Mystery of the Earth's AgeNo ratings yet

- Analogy in Archaeological Interpretation. AscherDocument10 pagesAnalogy in Archaeological Interpretation. AscherPaula TralmaNo ratings yet

- 10 1 1 494 5652 PDFDocument78 pages10 1 1 494 5652 PDFvalentinoNo ratings yet

- Times of History, Times of Nature: Temporalization and the Limits of Modern KnowledgeFrom EverandTimes of History, Times of Nature: Temporalization and the Limits of Modern KnowledgeAnders EkströmNo ratings yet

- Whose Science IsDocument26 pagesWhose Science Ismybooks12345678No ratings yet

- Paul Bahn Ed The History of Archaeology An IntroduDocument4 pagesPaul Bahn Ed The History of Archaeology An IntroduSoumitri SahaNo ratings yet

- The Nile: Natural and Cultural Landscape in EgyptFrom EverandThe Nile: Natural and Cultural Landscape in EgyptHarco WillemsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Man and Nature in The Middles AgesDocument27 pagesMan and Nature in The Middles AgesJorge CavalheiroNo ratings yet

- The Meaning of Fossils: Episodes in the History of PalaeontologyFrom EverandThe Meaning of Fossils: Episodes in the History of PalaeontologyNo ratings yet

- Arabic Astronomical and Astrological Sciences in Latin Translation: A Critical BibliographyFrom EverandArabic Astronomical and Astrological Sciences in Latin Translation: A Critical BibliographyNo ratings yet

- Ancient Egyptian ScienceDocument621 pagesAncient Egyptian Sciencekhaledgamelyan100% (4)

- Babylonian Astronomical Compendium MUL - APINDocument444 pagesBabylonian Astronomical Compendium MUL - APINNicolaNo ratings yet

- © 1936 Nature Publishing GroupDocument1 page© 1936 Nature Publishing GroupViorelDiorducNo ratings yet

- Geology in the Nineteenth Century: Changing Views of a Changing WorldFrom EverandGeology in the Nineteenth Century: Changing Views of a Changing WorldRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- History of ArchaeologyDocument25 pagesHistory of Archaeologyanon_714254531100% (1)

- Magli-JHA54 1Document2 pagesMagli-JHA54 1Ugo FanzisNo ratings yet

- Cosmology and Controversy: The Historical Development of Two Theories of the UniverseFrom EverandCosmology and Controversy: The Historical Development of Two Theories of the UniverseRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Studies in History and Philosophy of Science: Daniel SpeldaDocument10 pagesStudies in History and Philosophy of Science: Daniel SpeldaAldo MartínezNo ratings yet

- Ascher 1961 - Analogy in Archaeological InterpretationDocument10 pagesAscher 1961 - Analogy in Archaeological Interpretationpharetima100% (1)

- Wilson - An Alchemical Manuscript by Arnaldus de BruxellaDocument188 pagesWilson - An Alchemical Manuscript by Arnaldus de BruxellaRafael Marques GarciaNo ratings yet

- Fact, Truth, and Text The Quest For A Firm Basis For Historical Knowledge Around 1900Document29 pagesFact, Truth, and Text The Quest For A Firm Basis For Historical Knowledge Around 1900Jason Andres BedollaNo ratings yet

- Antiquarios Xvii Peter BurkeDocument25 pagesAntiquarios Xvii Peter Burkejulianamm28No ratings yet

- A Popular History of Astronomy During the Nineteenth Century Fourth EditionFrom EverandA Popular History of Astronomy During the Nineteenth Century Fourth EditionNo ratings yet

- (Hellenic Studies) Gregory Nagy - Plato's Rhapsody and Homer's Music - The Poetics of The Panathenaic Festival in Classical Athens (2002, Center For Hellenic Studies)Document21 pages(Hellenic Studies) Gregory Nagy - Plato's Rhapsody and Homer's Music - The Poetics of The Panathenaic Festival in Classical Athens (2002, Center For Hellenic Studies)yakarNo ratings yet

- Primitive Time-reckoning: A study in the origins and first development of the art of counting time among the primitive and early culture peoplesFrom EverandPrimitive Time-reckoning: A study in the origins and first development of the art of counting time among the primitive and early culture peoplesNo ratings yet

- William A. McDonald, George R., Jr. Rapp - Minnesota Messenia Expedition - Reconstructing A Bronze Age Regional Environment-Univ of Minnesota PR (1972) PDFDocument417 pagesWilliam A. McDonald, George R., Jr. Rapp - Minnesota Messenia Expedition - Reconstructing A Bronze Age Regional Environment-Univ of Minnesota PR (1972) PDFRigel Aldebarán100% (1)

- The New Archaeology and The Classical ArchaeologistDocument8 pagesThe New Archaeology and The Classical ArchaeologistMina MladenovicNo ratings yet

- Writing History in The AnthropoceneDocument27 pagesWriting History in The AnthropoceneJoão Francisco PinhoNo ratings yet

- Ancient Egyptian ScienceDocument621 pagesAncient Egyptian ScienceArtist Metu100% (9)

- Assignment 3Document13 pagesAssignment 3Diya VinodNo ratings yet

- New Directions in Cypriot ArchaeologyFrom EverandNew Directions in Cypriot ArchaeologyCatherine KearnsNo ratings yet

- Einstein Was Right: The Science and History of Gravitational WavesFrom EverandEinstein Was Right: The Science and History of Gravitational WavesNo ratings yet

- Annales and The Writing of Contemporary History - WesselingDocument11 pagesAnnales and The Writing of Contemporary History - Wesselingrongon86No ratings yet

- Making Natural Knowledge: Constructivism and the History of Science, with a new PrefaceFrom EverandMaking Natural Knowledge: Constructivism and the History of Science, with a new PrefaceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- Baucom - 2014 - History 4° Postcolonial Method and Anthropocene TDocument20 pagesBaucom - 2014 - History 4° Postcolonial Method and Anthropocene TGessica AlvesNo ratings yet

- When Historiography Met Episte - Bordoni, Stefano - 6288 PDFDocument347 pagesWhen Historiography Met Episte - Bordoni, Stefano - 6288 PDFFrederico Duarte100% (1)

- Ascher Analogy in Archaeology PDFDocument10 pagesAscher Analogy in Archaeology PDFMelchiorNo ratings yet

- Aims in Prehistoric Archaeology TriggerDocument12 pagesAims in Prehistoric Archaeology TriggersiminaNo ratings yet

- Georges Cuvier, Fossil Bones, and Geological Catastrophes: New Translations and Interpretations of the Primary TextsFrom EverandGeorges Cuvier, Fossil Bones, and Geological Catastrophes: New Translations and Interpretations of the Primary TextsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- 'John Donne's Verdict On Tycho Brahe' No Astronomer Is An IslandDocument18 pages'John Donne's Verdict On Tycho Brahe' No Astronomer Is An IslandManticora MvtabilisNo ratings yet

- The Oxford Handbook of The Bronze AgeDocument4 pagesThe Oxford Handbook of The Bronze AgeMisleine KreichNo ratings yet

- Ascher Analogy 1961Document10 pagesAscher Analogy 1961Francois G. RichardNo ratings yet

- World History For International Studies IntroductionDocument18 pagesWorld History For International Studies IntroductionJaskaran BrarNo ratings yet

- A History of Greek Mathematics, Volume I: From Thales to EuclidFrom EverandA History of Greek Mathematics, Volume I: From Thales to EuclidRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- History of Classical PhilologyDocument520 pagesHistory of Classical Philologypetitepik100% (1)

- Scenes from Deep Time: Early Pictorial Representations of the Prehistoric WorldFrom EverandScenes from Deep Time: Early Pictorial Representations of the Prehistoric WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- 4th International Conference On The Science of ComputusDocument16 pages4th International Conference On The Science of Computusa1765No ratings yet

- Rewriting The Past For The Changing PresentDocument12 pagesRewriting The Past For The Changing PresentSzilágyi OrsolyaNo ratings yet

- HotsDocument74 pagesHotsgecko195No ratings yet

- Lista Materijala WordDocument8 pagesLista Materijala WordAdis MacanovicNo ratings yet

- Rizal Course ReviewerDocument6 pagesRizal Course ReviewerMarianne AtienzaNo ratings yet

- The American New CriticsDocument5 pagesThe American New CriticsSattigul KharakozhaNo ratings yet

- SSP ReviwerDocument40 pagesSSP ReviwerRick MabutiNo ratings yet

- Recurrent: or Reinfection Susceptible People: Adult With Low Im Munity (Especially HIV Patient) Pathologic ChangesDocument36 pagesRecurrent: or Reinfection Susceptible People: Adult With Low Im Munity (Especially HIV Patient) Pathologic ChangesOsama SaidatNo ratings yet

- ERP Test BankDocument29 pagesERP Test BankAsma 12No ratings yet

- Schedule Risk AnalysisDocument14 pagesSchedule Risk AnalysisPatricio Alejandro Vargas FuenzalidaNo ratings yet

- Letters of ComplaintDocument3 pagesLetters of ComplaintMercedes Jimenez RomanNo ratings yet

- Richards and Wilson Creative TourismDocument15 pagesRichards and Wilson Creative Tourismgrichards1957No ratings yet

- PCA Power StatusDocument10 pagesPCA Power Statussanju_81No ratings yet

- Cap 1 Intro To Business Communication Format NouDocument17 pagesCap 1 Intro To Business Communication Format NouValy ValiNo ratings yet

- NUR 200 Week 7 Practice Case StudyDocument2 pagesNUR 200 Week 7 Practice Case StudyJB NicoleNo ratings yet

- The Passive Aggressive Disorder PDFDocument13 pagesThe Passive Aggressive Disorder PDFPhany Ezail UdudecNo ratings yet

- Instructional MediaDocument7 pagesInstructional MediaSakina MawardahNo ratings yet

- Gamma Ray Interaction With Matter: A) Primary InteractionsDocument10 pagesGamma Ray Interaction With Matter: A) Primary InteractionsDr-naser MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Conspicuous Consumption-A Literature ReviewDocument15 pagesConspicuous Consumption-A Literature Reviewlieu_hyacinthNo ratings yet

- Qsen CurriculumDocument5 pagesQsen Curriculumapi-280981631No ratings yet

- Malaria SymptomsDocument3 pagesMalaria SymptomsShaula de OcampoNo ratings yet

- Sigmund Freud 1Document3 pagesSigmund Freud 1sharoff saakshiniNo ratings yet

- Swimming Pool - PWTAG CodeofPractice1.13v5 - 000Document58 pagesSwimming Pool - PWTAG CodeofPractice1.13v5 - 000Vin BdsNo ratings yet

- Gesture and Speech Andre Leroi-GourhanDocument451 pagesGesture and Speech Andre Leroi-GourhanFerda Nur Demirci100% (2)

- BA BBA Law of Crimes II CRPC SEM IV - 11Document6 pagesBA BBA Law of Crimes II CRPC SEM IV - 11krish bhatia100% (1)

- Projectile Motion PhysicsDocument3 pagesProjectile Motion Physicsapi-325274340No ratings yet

- Mushoku Tensei Volume 2Document179 pagesMushoku Tensei Volume 2Bismillah Dika2020No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan1 Business EthicsDocument4 pagesLesson Plan1 Business EthicsMonina Villa100% (1)

- ContinentalDocument61 pagesContinentalSuganya RamachandranNo ratings yet

- Football Trading StrategyDocument27 pagesFootball Trading StrategyChem100% (2)

- Instructional Supervisory Plan BITDocument7 pagesInstructional Supervisory Plan BITjeo nalugon100% (2)

- Colour Communication With PSD: Printing The Expected With Process Standard Digital!Document22 pagesColour Communication With PSD: Printing The Expected With Process Standard Digital!bonafide1978No ratings yet