Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Maximilian Hartmuth Tez

Uploaded by

stardi29Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Maximilian Hartmuth Tez

Uploaded by

stardi29Copyright:

Available Formats

1HL BALKANS IN AN AGL OI BAROQUL?

1RANSIORMA1IONS IN ARCHI1LC1URL,

DLCORA1ION, AND PA11LRNS OI

PA1RONAGL AND CUL1URAL

PRODUC1ION IN O11OMAN LUROPL,

J7J8-J8S6

by

MAXIMILIAN HAR1MU1H

A 1hesis Submitted to the

Graduate School o Social Sciences

in Partial lulillment o the Requirements or

the Degree o

Master o Arts

in

Anatolian Ciilizations and Cultural leritage Management

Ko Uniersity

December 2006

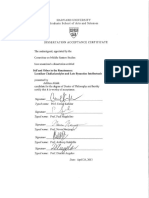

Ko Uniersity

Graduate School o Social Sciences

1his is to certiy that I hae examined this copy o a master`s thesis by

Maximilian lartmuth

and hae ound that it is complete and satisactory in all respects,

and that any and all reisions required by the inal

examining committee hae been made.

Committee Members:

Date:

Gnsel Renda, Ph. D. ,Adisor,

Alicia Simpson, Ph. D. ,Adisor,

Machiel Kiel, Ph. D.

Lucienne 1hys-Senocak, Ph. D.

\onca Koksal, Ph. D.

iii

Abstract

1his study aims to shed light on transormations in architecture and architectural

decoration in the Ottoman Balkans during the eighteenth and the irst hal o the

nineteenth century. 1hat this is a period linked to imperial decline on one hand, and to

national reials` on the other, has had a considerable impact on the interpretation and

assessment o the art o this period in modern historiography. It is the aim o this thesis

to challenge some o these interpretations and analyze this art primarily within its socio-

cultural context. Lxplanations will also be sought as to why Baroque orms exerted such

a strong inluence in the region when they had already aded out in \estern Lurope.

Rather than westernization`, decline, or national reial`, alternatie causes and

moties will be sought or the deelopment o the art o this period. As the agents o

change, actors such as merchants, notables, builders, decorators, bandits, and

guildspeople will be explored instead o the more traditional empires or nations. Rather

than mere descriptions o buildings, trends, and deelopments embedded in established

historical narraties, the art and architecture o this period will be analyzed in the

ramework o changing dynamics and patterns o patronage and cultural production,

centres and peripheries, the construction system, and mechanisms o exchange with the

non-Ottoman world.

i

zet

Bu alisma, onsekizinci yzyil e ondokuzuncu yzyilin ilk yarisinda Osmanli Donemi

Balkan topraklarinda mimarlik e mimari dekorasyon alanlarinda gorlen degisimlere

isik tutmayi amalamaktadir. Bu donemin, bir yandan imparatorlugun oksyle, diger

yandan ulusal canlanmalarla baglantili olmasi, soz konusu sanatin modern tarih

yaziminda yorumlanmasi e degerlendirilmesinde olduka etkili olmustur. Bu yorumlarin

bazilarinin sorgulanmasi e bu sanatin kendi sosyokltrel baglaminda analiz edilmesi

hedelenmektedir. Bununla beraber, Barok ormlarinin, Arupa`da oktan sona ermis

olmalarina ragmen, neden bu kadar kuetli bir etkiye sahip olduklari sorusuna ceaplar

aranacaktir. Bu donem sanatinin gelisimini ortaya koymak iin Batililasma`, oks ya da

ulusal canlanma` gibi tanimlamalar yerine, alternati nedenler e drtler

arastirilacaktir. Degisimin temsilcileri olarak imparatorluklar ya da uluslar yerine,

tccarlar, ayanlar, dlgerler, nakkaslar, eskiyalar e loncalar incelenecektir. \erlesmis

tarihi anlatimlarda gorlen yapilarin, akimlarin e gelisimin salt tanimlari yerine, donemin

sanat e mimarisi, degisen dinamikler e himaye modelleri, kltrel retim, birincil e

ikincil merkezler, insa sistemi e Arupa ile olan degisim mekanizmalari ereesinde

analiz edilecektir.

1able of Contents

PRLIACL..........................................................................................................................................VII

IN1RODUC1ION...............................................................................................................................1

J. A WINDOW 1O 1HL WLS1....................................................................................................10

1.1. 1lL POLI1ICAL PRLLUDL 1O CUL1URAL ClANGL: 1683-118......................................................10

1.2. 1lL 1ULIP LRA` ,118-130, AND I1S RLPLRCUSSIONS IN 1lL PROVINCLS...............................15

1.2.1. 1be .tavbvt of .bvet ava Davat brabiv Pa.ba15

1.2.2. 1be /vtti,e of atit erif Pa.ba at vvev 20

1.2.. 1be Davvbe Privciatitie. vvaer Pbavariote rvte 24

1.3. DLVLLOPMLN1S ON 1lL LDGL Ol 1lL O11OMAN \ORLD........................................................30

1..1. etgraae 111: frov Ottovav to aroqve cit, ava bac/30

1..2. Dvbrorvi/ ava tbe eregoriva34

1.4. RLCAPI1ULA1ION .......................................................................................................................38

2. O11OMAN BAROQUL AND BLYOND...............................................................................40

2.1. lIS1ORICAL lRAML\ORK...........................................................................................................40

2.2. 1lL O11OMAN BAROQUL`.......................................................................................................43

2.2.1. t. cbaracteri.tic. ava tace iv bi.toriograb, 43

2.2.2. 1be ivact of tbe Ottovav aroqve ov vovMv.tiv.` ava rorivciat arcbitectvre 48

2.3. ON OR1lODOX ClRIS1IAN CUL1URL IN 1lL LIGl1LLN1l CLN1UR\........................................52

2..1. 1be erbiav aroqve ava tbe icovo.ta.i. a. er.atfaaae 52

2..2. 1be ri.e ava fatt of Mo.cbooti.57

2.4. RLCAPI1ULA1ION .......................................................................................................................60

2.5. A NO1L ON 1lL O11OMAN lOUSL`.........................................................................................62

3. BANDI1RY, AYANLIK, AND A PRO1O-BOURGLOISIL: 1HL BALKANS BLIORL 1HL

RLIORMS...........................................................................................................................................66

3.1. 1lL K.RDZ.]11O AND 1lL lOR1IlILD lOUSL: D\LLLINGS AROUND 1800 AND 1lL PLACL Ol

AR1 IN AN AGL Ol INSLCURI1\..........................................................................................................66

3.2. PROVINCIAL NO1ABLLS AND MLRClAN1S AS NL\` PA1RONS Ol RLPRLSLN1A1IVL

ARClI1LC1URL..................................................................................................................................73

3.2.1. ARClI1LC1URAL PA1RONAGL Ol 1lL A\AN AND I1S PLACL IN O11OMAN AR1 .......................79

.2.1.1. oavviva vvaer .ti Pa.ba79

.2.1.2. 1iaiv vvaer O.vav Paravtogtv 85

.2.1... b/oaer ava Prirev vvaer tbe v.batti ava Rotvtta 88

.2.1.1. Pretivivar, covctv.iov ava a vote ov Mebvet .ti`. /vtti,e iv Karata 91

3.2.2. 1lL 1lLSSALO-LPIRO1L-MACLDONIAN RLGION IN 1lL LAS1 QUAR1LR Ol 1lL LIGl1LLN1l

CLN1UR\...........................................................................................................................................96

3.3. NL\ 1RLNDS IN ARClI1LC1URAL DLCORA1ION.......................................................................102

..1. 1rav.forvatiov. iv Ottovav art ava it. ai..evivatiov to tbe rorivce. 102

..2. 1be .tbaviav tava. at tbe ea/ of .tavic cvttvre iv tbe ovtbre.t at/av.110

3.4. ON 1lL ARClI1LC1S` AND PAIN1LRS` Ol MANSIONS AND MOSQULS IN 1lL LA1L O11OMAN

BALKAN PROVINCLS........................................................................................................................120

3.5. RLCAPI1ULA1ION .....................................................................................................................131

4. RLORGANIZA1ION (1ANZIMA1) AND RLBIR1H (VAZRAZDANL) ...........................135

4.1. 1lL BULGARIAN NA1IONAL RLVIVAL` AND I1S ARClI1LC1URAL MANIlLS1A1IONS ..............137

4.2. SLRBIA UNDLR MILOS OBRLNOVIC...........................................................................................157

4.3. 1lL BOSNIAN LXCLP1ION........................................................................................................164

4.4. 1lL RL1URN` Ol 1lL MONUMLN1AL ClURCl .......................................................................171

4.5. RLCAPI1ULA1ION .....................................................................................................................178

i

CONCLUSION.................................................................................................................................182

ILLUS1RA1IONS............................................................................................................................188

BIBLIOGRAPHY .............................................................................................................................226

MAP WI1H PLACLS MLN1IONLD IN 1HL 1LX1................................................................244

ii

Preface

1he prehistory o the idea or taking up this speciic topic as subject or a later thesis

began a ew years ago on a trip around Bulgaria. \ith a riend rom Soia insisting on

showing us her hometown, Sumen, haing arried there she directed us towards two

monuments she ound representatie o her town. One was a communist-period

memorial generously oerlooking the town, the other was the mosque o Seri lalil

Pasha, the only surior o more than 40 mosques still only a century ago. Now I had

been amiliar with the general characteristics o Ottoman mosques in the Balkans due to

a year-long stay in post-war Sarajeo and, admittedly, had ound them all to be airly

alike, but what I saw in the interior o the mosque at Sumen was dissimilar rom what I

had preiously come to know. Some o the decoration and motis elt oddly amiliar,

and in the concise lealet the keeper had proided us with upon entering, a preliminarily

satisactory answer was obtained in the classiication o the style as Islamic Baroque`.

Dierent rom the plain exteriors o 1urkish houses` I had preiously come across in

Bosnia and Serbia were then also some o the residences on the next stop on the

itinerary, Plodi. Lager to learn more about what I had seen back home, I stumbled

upon publications mentioning not only a Bulgarian Baroque`, but a 1urkish Baroque`

and Serbian Baroque` as well, all terms I had ell upon at some earlier point, but neer

had suspected a real correlation, them maybe orming part o a general, regional trend in

a speciic period. 1his, ater all, would also hae meant that what is so oten, i

indirectly, suggested in the histories o Southeast Lurope, namely an isolation o the

peoples o Ottoman Lurope rom the art and architecture o Lurope so as to explain

why the Balkans townscapes look so unamiliar to us`, would not be entirely accurate.

Beginning my research on this Baroque inluence`, soon came the realization that there

is much more to it than merely an occidentalist ad, akin to the 1urquerie in the west.

iii

In regional and national histories the Balkan societies` changeoer rom oriental` to

Luropean` is more oten than not portrayed as a reasonably clear break, as could be

expected rom someone supposedly breaking away rom the bondage o domination by

an alien ciilization, into reedom. Other than as an early stage in the liberation`

moements o subjected peoples, little space has been laished on the cultural history o

the eighteenth century Balkans. 1o declare nationalist-secessionist sentiment as the

deining entity in the eeryday lies o indiiduals at that period, howeer, is in all

probability delusional. labitually, as i requiring no urther periodization, the whole

hal-millennial period o Ottoman-Balkans culture is presented as a monolith.

lortunately, also a ast body o more enlightened literature exists, ew o which,

howeer, speciically dealing with the post-classical, pre-1anzimat cultural history o

Ottoman Lurope. Much o this thesis thus consists o piecemeal inormation, oten

rom quite unrelated sources, collected oer a period o three years. Only towards the

end o this research I could grasp the larger picture, the interrelation between dierent

actors ,and not only in terms o culture, art and architecture,, and eentually had to

reise many truths` that I had held or such through preious readings. It is the

purpose o this thesis to communicate and share these insights, and I am let to hope

that the arguments brought orward throughout this discussion will be conincing or

the reader.

1he necessary prerequisites or this enterprise I ound during my two-year residence at

Ko Uniersity in Istanbul. 1hat Gnsel Renda, an internationally renowned art

historian o the late Ottoman period came to be irst one o my proessors and

eentually one o my adisors proed a ortunate instance. Continuing the study o

established areas o interest in a preiously unamiliar enironment has also proided

ix

me with a new and dierent, maybe more Ottoman`, perspectie, which many works

on the Balkans produced in the region` or in the \est` perhaps lack. Occasional

stays in Vienna, on the other hand, hae enabled me to access an oten ery dierent

body o literature rom that ound in collections in Istanbul. It should also be noted that

throughout my research I hae, without exception, only made ery positie experiences

with the sta o libraries the collections o which proided the essentials or my work:

in Vienna these were the Austrian National Library, the main library o the Uniersity o

Vienna, the libraries at the departments or Art listory, Last- and Southeast Luropean

listory, 1urkology, Byzantine Studies, and een the city-run Public Library proided or

some surprising discoeries. In Istanbul, these were the libraries o the Ko, Bogazii,

Sabanci, Bilgi, and Mimar Sinan uniersities as well as that o the American Research

Institute in 1urkey ,ARI1, and the Institut lranais d`Ltudes Anatoliennes ,IlLA,.

Resources that otherwise could hae been located only with enormous eorts hae been

made aailable to me through the article- and inter-library loan request system at Ko

Uniersity`s Suna Kira Library, personiied by Ayla 1ekibasi, whose support and

switness, despite my seemingly neer-ending requests, must be commended. I am

urthermore indebted to Alicia Simpson, my second adisor, or giing this work a

thorough reading and making constructie suggestions or improements, and Ayse

Dilsiz or help with translations rom 1urkish and all other kinds o support during the

writing-process.

Next to publications in Lnglish, German, and lrench, considerable use has been made

o sources in the 1urkish, Serbian-Croatian-Bosnian, Bulgarian, and Macedonian

languages. 1here exist a ew interesting sources in Italian and a ast amount in Greek

x

which, regrettably, could not be accessed.

1

In the case o Greek publications, howeer,

now and then substantial summaries in Lnglish or lrench are included.

2

Gien the

inolement o such number o languages and scripts, a consistent transliteration or

consistent use o region-speciic terms in one o the releant languages is almost

impossible. lor much related to the Ottoman period, modern 1urkish terms hae been

gien preerence. In the transliteration o Bulgarian Cyrillic, which, unlike Serbian

Cyrillic, does not hae a generally accepted Latin equialent, the mode more accepted

among linguists o Slaic languages has been chosen oer the international` option

,much like Russian transliterated into Lnglish,. \here applicable, Bulgarian letters hae

been reproduced as what they would look like in other Slaic languages written in the

Latin alphabet ,m ~ s, u ~ c, ~ z,. 1he problematic` + ,equialent to the 1urkish t,

has been transliterated as , and not as u, a, i, or y, in order to be clear which original

character is being reerred to.

lor those not amiliar with the pronunciation o special characters ,diacritics, in the

Latin,ized, alphabets o the 1urks, Albanians, Romanians, and the south Slas, a small

,and simpliied, chart should proide guidance or the correct reading or reproduction

o words requently used in this work:

1

Among the works in Italian are studies o mosques in 1etoo, Samoko, and Kaala. lor reerence,

these can be ound in the bibliography as articles by Scarcia ,1981, and Curatola ,1981,, and the book by

Bruni ,2003,. Also Roskoska's concise book` ,46 pages, on the mosque at Samoko ,19,, although

published in German, lrench, and Lnglish, could not be located in libraries accessible to me. \hile all

these are key monuments on which inormation can be ound in greater detail also in the other sources I

used, the reader should keep in mind that the aorementioned works may include additional inormation.

2

1his was, or example, the case with Moutsopoulos ,196,. 1he citations rom this book thus reer to

the chapter-length Lnglish summary.

xi

Slaic languages 1urkish Lnglish

s sh

c ch or tch

c ,serb., - similar to the ch-sound in uture`

d ,serb., - similar to the dj-sound in orge`

,bulg., t ery short or other owel

- g not pronounced, lengthens preceding owel

Dz c dj as in jungle`

long a ,not used anymore,

1he Romanian is pronounced like the 1urkish t, the Albanian like a short German

, the gj like the Lnglish dj. In the case o Albanian place-names there exist two

simultaneously used ersions ,e.g. Kor ~ Kora,, which, i he,she is used to another,

should not surprise the reader. In the case o Gjirokastr, this ersion has been

preerred oer Gjirokastra`. In the case o 1irana, howeer, the internationally

accepted 1irana rather than 1iran` has been used. \here places hae accepted

equialents in Lnglish, such as Belgrade ,serb. Beograd, or Bucharest ,rom. Bucuresti,,

these orms hae been gien preerence. I will use both Istanbul and Constantinople,

gien that there neer was one name used by eeryone, and in rare occasions

Constantinople` seems more adequate. Mistakes and inconsistencies in transliterations

and translations, or any mistakes this work might possibly suer rom, are the sole

responsibility o the author.

1

Introduction

1his study aims to shed light on deelopments in architecture and architectural

decoration in the Ottoman Balkans in the pre-modern era. 1he period coered is

roughly the eighteenth and irst hal o the nineteenth century. As this thesis aims to

demonstrate, this is not a random choice but indeed a period o a reasonably distinct

isuality and dierent dynamics, and with a airly clear beginning and closing stage. As

the endpoint has been determined the year 1856, the year o the proclamation o the

Islahat edict, ater which the art and architecture o the Ottoman Christian subjects

reolutionarily change. In this age o already institutionalized westernization in the

Ottoman Lmpire, howeer, also in the architecture o mosques, residences, and

administratie buildings there are perceptibly new directions. At the beginning o the

narratie stands the year 118, the start o the 1ulip Lra`, in which among rulers and

administrators a noel approach to the non-Ottoman world deelops as a result o

incisie changes in Ottoman realities ater the ailed siege o Vienna in 1683, ultimately

resulting in a loss o substantial territory to a strengthened enemy in the north.

Both Kiel ,1985, and Bouras ,1991, justiy the year 100 as the chronological termini o

their respectie sureys arguing that it makes little sense to go beyond this date which,

taken symbolically, witnesses drastic breaches. \hile Kiel ,1985:1, assesses the

Ottoman iteenth, sixteenth, and seenteenth centuries as a period that stands out as

more or less homogenous`, the eighteenth century is stated to mark the beginning o

proound changes in society, thinking and art`. It is interesting that Kiel ,1990a:289-90,

urther seems to dierentiate between Ottoman art in the Balkans and art in the late

Ottoman Balkans: 1he ormer is said to witness a slow but steady decline` beginning

2

in the seenteenth century, while, writing more speciically o Albania, where only ater

that century a massie need or Islamic inrastructure arises, he explains the

subsequently dierent spirit o Albanian-Ottoman art by inerring that the imperial

centre could no longer guide the work in the proince` since Ottoman ciilization

had declined`.

3

\hat or whose art was it then \as it a genuinely Balkan art with its

own dynamics or simply a proincial relection o general post-classical Ottoman

trends

\hat concerns Christian architecture and art ,which otherwise will not be the at the

centre o this study,, Vryonis ,1991:30, similarly conirms a a certain decline in the

quality o the art` ater 100, which he explains by reerring to a rapid increase in the

number o artists, most o who were rom rural origins. In contrast to both the Muslim

and Christian religious art and architecture o this period, the residential structures

,traditional housing` or ernacular`,, usually receie a rather enthusiastic ealuation.

1his is, on one hand, certainly due to their classiication as traditional` ,whose tradition

notwithstanding,, and, on the other hand, likely also due to the act that we are simply

let with ery ew suriing examples predating the late eighteenth century, whereby a

comparatie assessment would not really be easible. Scholars, howeer, seem to agree

that the houses built in the century ater 150 show the most deeloped orm o this

type, while the mass o earlier dwellings are belieed to hae been much humbler ,as

conirmed in depreciatie accounts o western traellers,. But also in the late period

these buildings, while in almost all cases a ersion o what has come to be known as

3

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries most buildings, including mosques, were indeed not anymore

built by architects sent rom Istanbul but by Christian masters rom the wider region. 1he preiously

highly centralized process, which accounts or the region-wide uniormity o classical-period mosques in

the Balkans, is described by Kiel ,1990c:xi-xii,, based on the analysis o detailed registers, as ollows:

Architects and workleaders, trained in the capital, were dispatched to the proince. Models o what to

build were sent with them . \ith the help o these models the indiidual patrons, or the state

commission, could decide what kind o mosque or ortress they wanted.`

3

the Ottoman house` ,a concept which will later be explained, show not one but a

ariety o styles, some are more traditional`, some more Baroque`.

Nonetheless, in these two assessments by Kiel and Vryonis, and without een yet citing

the much more dismissie ealuations o 1urkish architectural historians about their`

architecture in the late period, we can already discern a common indication that the

study o the art o this period is somewhat less rewarding. 1o demonstrate that such a

conception is erroneous, aside rom not ery helpul, will be one o the objects o this

study. \e are dealing with a dierent kind o art, less classical` than its predecessor

and sometimes more a olk art` than an academic` one. Less stale and codiied, more

secular and personal, it also attests to the itality o its age, particularly ater the 10s.

Remarkable works o creatiity are patronized by increasing segments o society and

produced by a steadily increasing number o non-ormally trained builders-decorators,

whose role and histories hae, I beliee, not been ully appreciated. Instead,

historiography has eery so oten interpreted their works as the artistic component o a

nationalist renewal among the Balkan Christian societies, a notion which will be

challenged in the last two chapters o this study.

1he same authors hae endeaoured to explain a seemingly low leel o productiity in

Christian architecture or much o the period o Ottoman rule in the Balkans -

stretching oer hal a millennium hardly to be considered an occupation`, as is still the

paradigm - with two reasons: 1, the annihilation o a local ,Christian, class to patronize

their` art,s,, and 2, seere Ottoman-Islamic laws that orbade the building o new

churches and made een the repair o older churches ery diicult. Both claims are,

admittedly, not entirely alse, but we will also see that realities sometimes diered. 1his

also includes the conception o the Ottomans purposeully isolating their subjects rom

4

the achieements contemporary Lurope made in culture, the arts, and sciences, whereby

the 1urks hae been made the scapegoats or the modern Balkan nations`

backwardness`. It is true that major artistic moements in Lurope, like the

Renaissance, pass the Ottoman Christians` isual culture largely unnoticed, but we will

see that in some parts o the Ottoman Balkans, at dierent times, iid exchange with

the \est, not only in commerce but in cultural ocabulary as well, was indeed possible.

In no instance more than in the Age o Baroque is this noticeably in the Balkans, or

really in Ottoman culture as a whole. Baroque motis can not only be ound in the

decoration o Christian merchants` houses or paintings and iconostases o Orthodox

churches, but in Muslim ,and Jewish, residences and houses o worship as well. \hat

we see there is an Ottomanized` relection o Baroque ideas. But, then, is the Ottoman

art o that period to be considered part o a wider Baroque sphere, which would include

other exports to non-Luropean destinations, like the Mexican Baroque` which, despite

Spanish origins, takes ery indiidual orms in the process o dislocation

4

I yes, why

then does this Ottoman Baroque` ,or the Bulgarian Baroque`, or that matter, only

show at a point in time when the Baroque in much o Lurope has already come to and

end

1his study`s prime objectie will not be to discern western inluences on architecture in

the Ottoman Balkans, or to locate and position the Baroque in the region`s eidently

changing isual culture ater 100. Rather, it will be concerned with mechanisms o

exchange, not only between Last` and \est` but within the Balkans and between

centres` and proinces` in the Ottoman world. 1he aim is to describe, interpret,

and,or explain why, when, and how changes occur and materialize in the toci o public

4

On the surprising aterlie o Baroque beyond its natural boundaries`, see larbison ,2003, cit. x,, esp.

chapters VII and VIII.

5

and eeryday lies o Ottoman subjects in the way they did. 1his will mean to try to

understand the society that produced these works o art and architecture, and not

merely to point out to amiliar eatures in certain trends and sweepingly attribute them

to an increasing western inluence emerging rom an imbalance o power between two

societies, whereby one eentually begins to culturally dominate the other.

In such an endeaour, much o the historiography generated in the region under

discussion - a region which the outside world mainly associates with conlict and

contesting nationalisms - is not a natural ally. Next to the works o art and architecture

to be treated herein, historiography and its readings o the cultural past must thus take a

prominent place. listoriographically, one crucial problem seems that our knowledge o

the Ottoman Balkans in the eighteenth century is ery limited, particularly i compared

to the ast amount o scholarship produced on the nineteenth century. Much o what

has been written on the period oten ocuses on the resurgence ,or emergence, o

national sentiments among the Balkan peoples, and certainly much more than on their

eeryday lies. In this sense, it is more a history o nations rather than a cultural history.

But also rom the other, Ottomanist iewpoint, laroqhi ,1995:29-30, had identiied

particular diiculties` in the expansion o our knowledge o the cultural history o the

eighteenth century, a paradox being that it is ery well documented but at the same time

relatiely little research has been made, particularly or the period ater 130. She

attributes this in part to that the oreign-inluenced art o that century had been

dismissed in the writings o nationalist Republican-period art historians, who classiied

that style as an alien import by a court orgetting national` traditions and borne by a

society whose liestyle was rowned upon by many contemporaries. Luropean

historians, on the other hand, were too much concerned with national-cultural

peculiarities to really appreciate this cosmopolitan style`. Not anymore solely identiied

6

with cultural decline, more recent research eentually began to appreciate this age

representing, in laroqhi`s words, the itality and elegance o a late period.`

Particularly in the last two-three decades a considerable amount o studies hae ocused

on Ottoman eighteenth-century culture. Scholars such as Maurice Cerasi, Shirine

lamadeh, Gnsel Renda, or Dogan Kuban hae contributed a great deal to our

knowledge o the art and architecture o this period which now appears to ascinate a

growing number o people.

5

Regrettably, the same can not be said or contemporary

deelopments in the proinces. In act, and aside rom a ew case studies, close to

nothing has been published on late Ottoman mosques in the Balkans. \ere it not or

the many publications by Machiel Kiel, the works o some \ugosla scholars like Andrej

Andrejeic, or the inentory o Ottoman monuments in Lurope prepared by the

1urkish researcher Lkrem lakki Ayerdi, we would not know much about the classical-

period mosques either.

6

Despite these essential contributions, still no comprehensie,

synthetic, and critical work, coering the whole region, that is, the region that it was

when this architecture deeloped, has been created to coney to us the history and the

character o Ottoman architecture in the Balkans. In 1urkish works on Ottoman

5

\hile noting that the recent surge o interest in the artistic and architectural production o the

eighteenth century has rescued this period rom its earlier characterization as an era o decline`, lamadeh

,2004:33-4, also criticizes that the emphasis placed on the inluence o Luropean culture and aesthetics

and on the role o the Ottomans' westernizing aspirations in inorming architectural change has

considerably eclipsed the extensie and multiarious nature o the century's deelopments ... 1o regard the

eighteenth century as a turning point in Ottoman interaction with Lurope is to ignore oer two centuries

o irtually continuous cultural and artistic contact.`

6

Admittedly, there hae been a couple o books published in 1urkey on the 1urkish` cultural heritage in

the Balkans ,e.g. \enisehirlioglu 1989, 1uran and Ibrahimgil 2001, (am 2000,, but these are rather

photographic essays with only ery little inormation on the buildings. A prominent exception, on

Ottoman architecture in the Balkans, Ayerdi`s our-olume inentory rom around 1980 remains the

basic source. Despite its age and his obious dislike o anything produced ater the seenteenth century,

sometimes expressed in open disgust, it is still much more inormatie and contains ar less mistakes than

the more popularly written works written ater it. In deence o these well-meant attempts, it must be

noted that during the Socialist period in Southeast Lurope the research possibilities or sureying these

countries` suspicious Ottoman architectural heritage were limited. Len the Dutchman Kiel ,1990c:x,

reported o haing been arrested and conined` and haing had his notes or ilms coniscated` in each

o the Balkan countries, or no other reason than taking photographs o Ottoman buildings.`

architecture examples rom the Balkans are conspicuously absent, implicitly suggesting

that this region did not play a signiicant role in its deelopment, a iew with which Kiel

,1990c:x, would sharply disagree.

Less or political reasons, also the church architecture o the eighteenth century remains

airly little studied, although much has been done in this ield in the last ew decades as

well. In contrast, traditional` dwellings are extraordinarily well researched, whereby we

were able to rely on extensie studies by the likes o Nikolaos Moutsopoulos, \iannis

Kizis, Sedad lakki Lldem, lalk Sezgin, Christo Pew ,Pee,, Georgi Arbalie, Pejo

Berbenlie, Anna Roskoska, Dusan Grabrijan, or Aleksandar Deroko. \hile consulted,

not all o them needed to be cited in this study, as the dwellings they speak o, although

in their readings they are Serbian, Bosnian, 1urkish, Greek, Albanian etc.

traditional,ernacular architecture, really constitute one main type with minor regional

dierences, which ,Cerasi 1998:149, explains as due to epoch and social class rather

than to region, climate, or ethnicity. A useul proision has been the olume .rcbitectvre

traaitiovvette ae. a,. bat/aviqve. ,1993,, to which many o the aorementioned contributed

a well-researched piece. Indicatie o the questionably productie approach o studying

these structures in the context o modern nation states` borders, which appeared where

they had been none at the time when these houses were built, howeer, is that each

country is represented by a chapter, but no synthesis rom these cases has been

attempted by way o a concluding chapter. 1he readers o many works like this will also

notice that only seldom exact ,or any, dates are gien or the houses coered, which

brings us to the next problem: dating. Inscriptions indicating the construction dates o

houses are rare, and in many places seem to become common only toward the mid-

nineteenth century. Inescapably, this poses an obstacle or tracing the deelopment o

residential architecture and its regional ariations. But also in terms o both Muslim and

8

Christian religious architecture, where we typically ind inscriptions with dates, dating is

sometimes problematic. 1hey can reer to the ounding date o the institution as well as

to later re-building ,repair`,, but are seldom clear on when the building acquired a

characteristic shape.

A repair` can mean in some cases that only minor changes hae

been made to the structure, in others that it was completely built anew. 1he same is

alid or the decorations o interiors. Many iteenth century mosques hae been

redecorated in the early nineteenth century and thereby in the contemporary style. In

some cases we know the dates o these redecorations with certainty, i mentioned in

chronicles or inscriptions, in others we can only guess.

8

In such cases one is let to

compare the decoratie eatures with similar designs in Istanbul or other parts o the

southern Balkans where exact dates are aailable. But also the interest in interior

decoration is a more recent deelopment, whereby only ew more comprehensie

studies hae been produced, mostly by 1urkish scholars and hence oten only partly

accessible to academics in the rest o the region. An additional problem is that we can

only guess how widespread such elaborately painted interiors were, or so many

buildings hae been lost either through wanton destruction ,mosques, or requent ires,

which hae let us only with a small sample o the residences which, to a large extent,

were built rom wood and thereore highly ulnerable. 1hese and other inescapable

problems accounting or the proisional disposition o many eentual conclusions must

be kept in mind by the reader.

1he act that some Ottoman inscriptions only proide dates encoded as chronograms adds a degree o

obscurity, as they are not always easy to decipher and are thereore occasionally misconstrued.

8

In the case o the 1ombul mosque at Sumen ,Bulgaria,, or example, we know that the structure dates

rom the 140s. But the interior decoration, eaturing some baroque motis and patterns as well as painted

landscape-panels, apparently dates rom a later point, possibly rom the early nineteenth century. And

although this is one o the ew mosques in Bulgaria which hae attracted considerable attention, there was

ound no hint to this decoration haing taken place at a later date in the literature consulted.

9

laing so presented the topics to be coered in the present study, it may appear to

some that, in the context o the limitations o a Master`s thesis ,time aailable or

research, capacity o researcher, etc.,, both the period - one and a hal centuries - and

the ast region coered were an exaggerated, i not pretentious rame i the aim is to

produce a really conclusie architectural surey, whereby more wisely a speciic case or

sub-region would hae been chosen. loweer, both the actors erioa and regiov, as must

lastly be stressed, are key hypotheses o this study, which will be less concerned with

descriptions o indiidual structures than with the aim o understanding the cultural-

historical context in which the works in question materialized.

10

J. A Window to the West

J.J. 1he political prelude to cultural change: J683-J7J8

\ith the treaty o Karlowitz ,1699, a new phase in Ottoman history begins. lor the irst

time an Ottoman Sultan ormally acknowledged his deeat and the permanent loss o

lands conquered by his ancestors rather than temporary withdrawal rom them. In the

negotiations at Karlowitz, and again in 130, the Ottomans, urthermore, or the irst

time accepted the mediation o a Luropean power, namely lrance, an almost permanent

ally o the sultans, on their behal. 1he borders emerging rom this treaty - the Saa-

Danube-Carpathians line - proed to be exceptionally long-lied. \ith the exception o

some Austrian gains

9

and the creation o a Neo-lellenic state in 1830 - long conined to

the southern portion o modern Greece - and notwithstanding internal autonomies, the

borders drawn at Karlowitz suried until the 1reaty o Berlin in 188. Not incidentally,

it is exactly this area which is routinely thought o as culturally Balkans`. 1he

Ottomanization` to take place in these last two centuries o 1urkish presence in the

Balkans was a process aided not least by the Balkan Christians trying to emulate the

Muslim upper classes, their houses and liestyle, as soon as economic potency permitted.

As a result or the deastation caused by the Austrian army penetrating deep into the

Balkan peninsula ater the second Ottoman siege o Vienna ,1683, had ailed, eminent

cities like Sarajeo or Skopje did not recoer or one and a hal centuries.

10

It is thus not

9

1he Banat o 1emesar in 118 and the northern Moldaian region henceorth known as Bukoina

were lost to the labsburgs in 15.

10

Classical-period Skopje had enjoyed oer-regional importance due to the good reputation o its Isakiye

veare.e. Ater those in Istanbul, Bursa, and Ldirne, it was reported to be the best in the empire ,Adanir

1994:155,. But laroqhi ,1995:88, notes that by the eighteenth century also Bursa and Ldirne had lost their

11

in these centres o the classical Ottoman period in the western Balkans that the most

noteworthy expressions in art and architecture o the eighteenth century are to be

expected. Instead, new ocal points emerged, and urban hierarchies began to shit. But

the Austrian adances in the Balkans also triggered signiicant eents whose cultural

implications still echo today. \hen the labsburg army was orced to retreat to north o

the Danube-Saa border ater a lrench attack on the western borders o the loly

Roman Lmpire, it was ollowed by many Balkan Christians leeing their homes out o

ear o retaliation or collaboration with the oreign intruders. In what became known as

the great migration` ,reti/a .eoba, some 30,000

11

Serbs let the core territories o their

medieal states, most prominently Kosoo, to settle in the newly labsburg territories

north o the 1699 border.

12

1here they were integrated into a dierent cultural and

social mainstream than their kinsmen remaining under Ottoman rule or almost two

more decades, accounting or an intra-Serbian cultural diision which still reerberates

today. But also Romanians and Croats were henceorth ound on both sides o the long-

lied Austrian-Ottoman border.

As a consequence o the treaty o Karlowitz, eighteenth century Southeast Lurope came

to be diided between two multiethnic empires. But although the two empires shared

many similar problems, to the outside obserer at the time the dierences were

proound` noted Jelaich ,1983:166-,. She continued by drawing a undamentally

polarized picture, which became the paradigm o modern historiography`s imagery:

role as centres o theological and juridical education. On the signiicance o classical-period Skopje, see

also Kiel ,2002,, esp. the concluding remarks ,p.41,.

11

Lxaggerated estimates claim a migration o up to 500,000 people. See Malcolm ,1998:140,156,.

12

1he depopulated areas in the central Balkans are then repopulated by montagnards rom surrounding

areas, mostly Albanians gradually conerting to Islam, constituting a demographic shit which was to

become the core problem o iolent conlicts three centuries later.

12

Most obious were the outward orms o two contrasting ciilizations. In the eyes o

educated Luropeans the Ottoman Lmpire was a backward, een barbarous, state ... 1he

custom o collecting heads and o staking out bodies and heads in public places reolted

citizens o countries where such actiities belonged to the past. Moreoer, Ottoman

cities were dirty, congested, and primitie in comparison with those o the \est.

Conspicuous display o wealth could be dangerous, luxury and wealth were conined to

the homes, where they could not be iewed by oreign eyes. In comparison, in

questions o style the labsburg Lmpire was one o the great centers o Lurope. In an

age o baroque culture, labsburg ciilization was splendid. 1he nobility could aord to

maintain magniicent residences and to endow the arts. 1here was also a comortable

middle class. Law and order were assured, bands o robbers did not roam at will. Public

oicials were supposed to uphold certain standards. Although corruption exists in all

societies, the Austrian serice was relatiely honest and eicient. General standards or

sanitation, cleanliness, and order were maintained at a high leel. In contrast, corruption

was blatant and open in Constantinople.`

Ortayli ,1994:9, predictably only partly subscribes to the totality o such assessment:

Briely put, in the late seenteenth century the Ottoman Lmpire was in social and

economic chaos, and there is no doubt that practically all its institutions were moing

towards collapse. But on the other hand, the rulers o the empire were able to come up

with brilliant and interesting examples o bureaucratic manipulation to cope with this

imminent threat. 1he decline o the state did not mean cultural decline, o course.

Ottoman society was in search o a new lie-style, and a new art and social culture was

emerging, which would come down through successie changes and eolutions to the

present day.`

1he political decline emanating in this period is routinely linked to the decay o old

Ottoman institutions that had accompanied the empire during its expansie period,

which - ater a seenteenth century o stagnation without signiicant territorial losses or

gains, except or Crete - really comes to an end with Karlowitz. 1he aer,irve system o

recruitment o able boys rom the Balkans countryside - many o which had become

some o the most capable and respected Ottoman oicials ater being brought up as

13

Muslims - had already been abandoned under Murat IV. In the eighteenth century

iziers and military commanders were mostly o 1urkish extraction. At the beginning o

this century Mustaa II also somewhat shockingly` ,Quataert 2000:43, conirmed

hereditary rights to the tivar. ,ie-holders,, the inancial backbone o a caalry that was

already militarily obsolete. \hile the tivar-system had been a pragmatic solution

encouraging and rewarding indiiduals` commitment in military campaigns, once the

empire ceased to expand it became obsolete.

\hereas sultans o the classical period had looked towards Rome, Paris now became a

reerence or things western. \hile Petersburg was not yet to play a signiicant role in

the region, another centre in the north became a ital point o reerence or the Balkan

Christians in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Despite the eentual retreat rom

territories already conquered by Austria in the late seenteenth century. 1his was

Baroque Vienna, mythiied as a Christian bulwark against the Muslim threat, and gaining

immense attraction or the Christians under Ottoman rule, or whom it became a major

intellectual centre in the course o the century.

lor a perspectie on the architecture o the irst hal o the eighteenth century we will

start with the Istanbul o Ahmet III as a centre o dissemination o trends then relected

in buildings in three cities in the east o the region: Sumen in northeast Bulgaria, and

Bucharest and Iasi in the Danubian Principalities ,the later Romania,. 1hat almost no

new building rom the western hal o the peninsula merits inclusion in this chapter

must be explained with that ater the deastations in the late seenteenth century the

minds may hae been set on rebuilding rather than on the construction o new icons.

13

13

One remarkably large rebuilding` project in Lepanto ,Inebahti, has been brought to our knowledge by

Kiel ,1991b,. During the Venetian occupation o the town ,168-100, apparently all Ottoman buildings

were either totally demolished or ruined. \hen it was then regained by the Ottomans a new start had to

14

loweer, a short section will be deoted to the architectural interactions between the

Adriatic coast and its Ottoman hinterland, which also continued in this period. Cultural

impulses rom a dierent geographical direction will be treated at the end o this

chapter. lor two decades the ery north o the region in question is temporarily

annexed by labsburg orces, and the Ottoman Belgrade was redesigned as an Austrian

Baroque city until returned to Ottoman soereignty in 139. Despite large-scale

demolitions, the empire therewith inherited an actually Baroque tradition in monuments

that were to remain part o the Ottoman possessions or another century and a hal.

made, and the sultan and his grand izier Koprl Amcazade lseyin Pasha laid the oundations or the

reial o Islamic lie in the town by erecting a number o schools mosques, baths, and other public

works, ruins o the buildings o the lseyin Pasha complex surie.

15

J.2. 1he 1ulip Lra (J7J8-J730) and its repercussions in the provinces

J.2.J. 1he Istanbul of Ahmet III and Damat Ibrahim Pasha

1he so-called 1ulip Lra` ,Lale Deri, gained notoriety or its extraagant pleasure-

loing liestyle and disinterest in war. It is not the accession o Ahmet III ,103,, a ruler

usually portrayed as rather passie and romantic, that is considered the beginning o this

period, but the assumption o oice o the liberalist Grand Vizier ,Nesehirli, Damat

Ibrahim Pasha in 118. 1o claim this era as the beginning o westernization in the

Ottoman Lmpire would not only be an oerstatement but would also ignore the

contacts that well existed already in the classical period. Indubitably, howeer, it is in the

1ulip Lra during which the cultural exchange is considerably accelerated, not least

through an embassy sent to lrance in 121. 1he mission o the enoy, \irmisekiz

Mehmet (elebi, was not only purely diplomatic, he was also entrusted to obsere the

ways and technologies o the lranks. \ith a similar curiosity to that which he was

greeted with in Paris, his .efaretvve, a detailed documentation o his obserations, was

receied back in Istanbul. Next to noting the dissimilarities in dining manners and the

attitudes to women, he was also greatly impressed by the streets, buildings, and palaces

,and their interiors,, some o which he had had the opportunity to enter as a priileged

guest.

\ith the readiness to accept and absorb new ideas a characteristic o the 1ulip Lra, a

time o extraordinary experimentation in Ottoman history` ,Quataert 2000:44,, the

court o Ahmet III becomes a meeting place or artists, poets, and intellectuals. In 126

the irst printing press in Ottoman script is introduced by Ibrahim Mteerrika, a

lungarian-born conert. Reportedly commissioned in the style o Versailles, Ibrahim

16

Pasha had a leisure palace ,Sa`dabad`, |Ill.1.1| built by or his Sultan on the other`

side o the Golden lorn, in contrast to preious Sultanic projects ar rom the walled

city. Unortunately, nothing has suried o this monument so central or modern

historiography`s thesis o a gradual westernization complementing imperial decline. Our

present knowledge o this structure owes much to the attempted reconstruction by

Lldem ,19, and painted illustrations by oreigners isiting the Istanbul o Ahmet III.

\e note that the exterior o the palace looks typically Ottoman, and it is in the interior

that the supposed Luropean inluence must hae been more apparent. More reealing,

we ind geometrical garden arrangements with planned lower beds, a noelty in

Ottoman conduct, or which Luropean models seem apparent.

14

lor Goodwin

,19:33,, still, the complex was only a clumsy imitation o only partially understood

ideas.`

1hanks to pictorial and textual eidence that we can re-enact that the palace consisted

o harem and .etavti/ ,male quarters,, around which were grouped a mosque, a garden

pailion, a large pool, a small ountain, as well as some 10 residences and gardens or

state oicials, built in a hitherto unseen style`, as a contemporary source ,in lamadeh

2004:38, attests. Luropean traellers o the period reported that the palace was

modelled ater a contemporary lrench palace, a set o whose plans had been brought

back rom Paris by Mehmet (elebi in 121, nine months beore the construction o

Sa`dabad ,Abode o lappiness`, began. Depending on the author, the supposed

model was Versailles, lontainebleau, or Marley-le-Roi. But historians or poets o the

Ottoman court, deoting more space to Sa`dabad than to any other building o the time,

14

I we look at an engraing o the Moldaian prince Cantemir`s palace |Ill. 1.1|, built beore 111, we

notice that garden arrangements in Istanbul must actually hae predated Sa`dabad. On this engraing we

een see a classicistic garden portal with a triangular pediment. On the history o this palace, see also

Goek ,198:126, or, directly, Cantemir ,134,.

1

neither oer any clue that a western prototype had sered as model, nor that it may

hae been related in some way to the architectural knowledge Mehmet brought back

rom his embassy to lrance ,lamadeh 2004:38-40,. Goodwin ,19:33,, in act,

asserts that |n|othing was arther rom the ideas o permanence and oerwhelming

pomp that created Versailles`, as he identiies the Kagithane area as really no more

than a ield o 13 tents since the kiosks were built o lathe and plaster, their railty

adding to the delight.`

Despite an indubitably increased interest in things western, Cerasi ,199:42, reminds

that - despite wars and dynastic hostility - it was really Persia that was regarded by the

aerage Ottoman, educated or not, as the symbol o enjoyment o nature and literature

and o reinement, and became the real point o reerence or the innoatie imagery o

the irst hal o the century.` Also in terms o the building o the 1ulip Lra, lamadeh

,2004, is not the irst to juxtapose the westernization` thesis with the suggestion not to

disregard ostensible eastern` reerences, notably Saaid Persia. 1he noticeably altering

reception o Lurope in this period should also not lead to the conclusion that the

attitude towards Christians in the empire would considerably change. Ahmet III issued

fervav. that limited the height o non-Muslims` houses so as to not be higher than

Muslims` houses and orbade Muslims to sell their houses to Christians ,Karaca

1995:33,. le also prohibited Christian Ottoman subjects rom conerting to

Catholicism ,Girardelli 2005:242, and, noting that some good-or-nothing` women

had also adopted arious innoations in their clothing, imitating Christians in the

deliberate eort to lead the public astray on Istanbul`s streets`, the Sultan issued a

decree speciying the precise widths and measurements o the items used or coats and

headgear ,Quataert 199:409,.

18

1he 1ulip Lra`s most isible legacy in the ormer capital`s cityscape are not the palaces,

o which none has suried into the present, but the ountains |Ill.1.2|.

15

In principle a

utilitarian building type, it was the ountain in which creatie minds discoered an ideal

object or experimentation. Deoid o religious connotation, it is thus the ountains and

not ,yet, the mosques where outside inluence irst become most apparent. \hile the

interest in water and ountains itsel is a quality o the Baroque age, an important

transormation o the type in Ottoman architecture is that, rather than as preiously

typically integrated into a wall, the now oten ree-standing ountains increasingly

created their own public space, as quasi-monuments. Goodwin ,19:34, already noted

the contrast between the curular and the straight` in the 120s ountains, but not yet

the low essential to truly baroque monuments. |Only| one o the patterns is new to

Ottoman architecture: it is the quantity which contrasts with the sober lack o ornament

o sixteenth-century ideal.` Nonetheless, not only the gradual swell in noel decoratie

elements, including increasingly sculptured suraces, but also the sheer inlation o new

ountains and their locations attest to a certain change during the 1ulip Lra. Cerasi

,199:41, reports o 216 new ountains alone built during the reign o Ahmet III in the

newly popular suburbs, whereto the well-to-do had relocated, permanently or not.

In the perspectie o the social historian Quataert ,2000:44,, the court society`s

suburban pleasure palaces ,the building o which the court had encouraged, were not

primarily a matter o changed preerences but o new methods. Also he points to a

lrench parallel, yet not in style but in the means o propping up legitimacy employing

the weapon o consumption:

15

1he habitual translation o the 1urkish .ebit into the Lnglish ountain` is in act a misnomer. 1ypically,

a .ebit is a small kiosk with grilles, rom behind which an attendant dispensed water. 1he proper term or

an actual ountain or tap that proides drinking water is e,ve. \ater house` may be a more appropriate

translation o .ebit, but since ountain` is so incontestably established in the literature it has been used

here as well.

19

Like the court o King Louis XIV at Versailles, that o the 1ulip period was one o

sumptuous consumption - in the Ottoman case not only o tulips but also art, cooking,

luxury goods, clothing, and the building o pleasure palace. \ith this new tool - the

consumption o goods - the sultan and grand izier sought to control the izier and

pasha households in the manner o King Louis, who compelled nobles to lie at the

Versailles seat o power and join in inancially ruinous balls and banquets. Sultan Ahmet

and Ibrahim Pasha tried to lead the Istanbul elites in consumption, establishing

themseles at the social center as models or emulation.`

Almost predictably, the lamboyance o the 1ulip Lra` was not to last long. Giing

oice to the resentment long elt by the clergy and the lower classes at the waste, the

launted wealth and the innoations regarded as contrary to morality and religious

precepts` ,Cerasi 199:44,, the junk dealer lalil instituted an uprising which ultimately

succeeded in its goal to dethrone Ahmet III and hae his Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha

decapitated.

20

J.2.2. 1he klliye of Halil erif Pasha at Sumen

1he short-lied 1ulip Lra` had ew repercussions in the Balkans. Not only due to the

deastations caused in the wars o the late seenteenth century, the time o really

monumental endowments in the Luropean proinces was more or less oer.

16

An

exception is the /vtti,e o lalil Seri Pasha ,1ombul Mosque`, at Sumen

1

in northeast

Bulgaria |Ills.1.4-6|, the largest Ottoman religious building in Bulgaria ,and the only o

ormerly more than 40 mosques in Sumen spared demolition,. Built where the two main

lines o communication in the town crossed, and according to the designs o an

unknown architect ,Ianoa 2004a:503,, the ensemble comprises a mosque, a veare.e

,religious high school,, a library, and a ve/teb ,primary school,.

18

1he 40m high minaret

rises rom the centre o the complex enclosed by walls. In addition to the date o

construction generally gien as ,140-,144, which would be too early or the maturity

o some o the occidentalizing wall paintings dominated by loral and egetal moties

,including tulips,, in which Kiel ,1989:42, beliees to identiy a Central Luropean

16

Kreiser ,199:61, had generally noted that, sae or a ew exceptions, the endowments o the late

period are o small dimension, and een a sultan with a relatiely long and relatiely successul reign, like

Mahmut I ,130-154, endowed little, according to a ra/fi,e transcript only a ew schools and libraries

with limited ollow-up costs.

1

Sumen, while presently hardly amiliar to anyone outside Bulgaria, should briely be credited with its

historical role as a leading Islamic city in the Luropean proinces o the Ottoman Lmpire. Particularly in

the eighteenth century it emerged as an important urban centre or the region and expanded north- and

eastward. 1he town acquired strategic importance during the Russian-1urkish wars between 168 and

188, when it was part o the ortiied quadrangle o Ruse-Varna-Silistra-Sumen. As a consequence o

these wars and the /araati conlict, many illages around Sumen were ruined, whereby the Christian

population, preiously restricted to the eastern part o town, increased and ormed new quarters. 1owards

the end o the nineteenth century, and into the period o Bulgarian independence, Sumen became one o

the centres o 1urkish education and o the 1urkish intelligentsia in Bulgaria ,Ianoa 2004a,. It is due to

the patronage o Seri lalil Pasha, who endowed a post or a calligraphy teacher in his eighteenth century

religious complex, that Stanley ,2003:135, attributes the subsequent emergence o an important school o

Qur`an production. Between the seenteenth and nineteenth centuries Sumen also was a centre o Suism

in northeast Bulgaria, which Georgiea and Sabe ,2003:322, explain as due to the city haing been the

winter camp o Ottoman troops in the course o the wars in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. At

that period it was unsuccessully attacked by Russian orces thrice, in 14, 1810, and 1828.

18

1he oundation deed or lalil Seri Pasha`s complex has been published by Duda ,1949:115-126,.

21

inluence haing reached this proince ia Istanbul.

19

Most elaborate around the

windows |Ill.1.6| and especially around the vibrab |Ill.1.5.|, or these works also a much

later date could be suggested.

In terms o the architecture, Stajnoa ,1990,, or good reasons, has linked the 1ombul

mosque to the Lale style` o Ahmet III, although, completed in 144, it appears more

than a decade ater that period ended` in Istanbul. \hile irst explaining the belated

appearance o such mosque with that architectural trends rom Istanbul reached the

proinces usually a bit later, more plausible is her suggestion o seeing the style as a

preerence o its patron. lalil Seri Pasha - born either in the illage o Madara or in

Sumen proper at an unknown date, died in 152 ,Ianoa 2004a:503, - had been part o

the court society during the 1ulip Lra as one o the most erent participants in all the

innoations o the period` ,Stajnoa 1990:22,. \hen he became the /etbvaa ,high-

ranking assistant, o the Grand Vizier or the second time he constructed the 1ombul

complex as well as an ensemble o buildings around it. It was said that columns and

blocks o stone had been brought rom the nearby ruins o the medieal Bulgarian

capitals Pliska and Presla as well as rom the Sumen ortress. lrom the 140s also date

the clock tower, a stone prism with a built-in drinking-ountain with rich ornamentation,

but not the Kursum cesma ,trk. /vr,vvtv e,ve.i, |Ill.1.|, a drinking ountain ,so called

or its original aade coered with leaden plates,, which with its low-relie Baroque

ornament dates rom 14.

lalil Seri Pasha was an outspoken admirer o Damat Ibrahim Pasha, to whom he een

dedicated some odes ,Stajnoa 1990:229,. It thus may not be all that coincidentally that

19

Ianoa ,2004a:503, also mentions a new inscription rom 12, composed by the local poet Ni`met.

Could this also be the date or the painted decoration on the interior, or or at least a part o which

22

probably the closest relatie to his mosque at Sumen is the one the same Ibrahim Pasha

built in 126, in his hometown Nesehir ,preiously Muskara, |Ill.1.3|,

20

and not in

Istanbul, where the 1ulip Lra has let ew noteworthy religious buildings. \hile both

mosques still eoke the spirit o classical Ottoman mosque architecture in most aspects

- Goodwin ,191:30-1, also declares that it were diicult to deine why the building is

o its own period and not classical` and that |o|nly certain details point to change` - it

is the slender corner turrets that appear a remarkable eature.

21

Much o what Kuran

,19:305,, writes o the mosque at Nesehir is thus equally releant or our building at

Sumen, while he urther elaborates on the dilemma o mosque architecture in the irst

hal o the eighteenth century:

\hat attracts the attention in Ibrahim Pasha Mosque is not so much an innoatie

eature or the absence o some essential classical element as a weakening o style. 1he

corner towers, which isually hold the mosque together in classical architecture, seem to

be unrelated to the whole structure, and rather than exerting weight rom the top, they

spring up like acroterions marking the corners. 1he eight domed-turrets holding the

corners o the octagonal drum likewise seem ornamental, not because they do not

perorm a structural unction, but because they rise aboe the cornice o the drum,

beyond the line o the dome`s lateral thrust. A similar process o elongation takes place

with the minaret, which is ar too tall compared with minarets o the classical era. 1his

type o change cannot be attributed to Luropean inluence. Beore all else, it is a

maniestation o boredom with a style which has gone on too long. 1he Mosque o

Ibrahim Pasha shows that its architect is not reacting against the classical style, yet he

20

lollowing laroqhi ,2004a:11,, Ibrahim, in act, had his /vtti,e modelled ater the mosques o sixteenth-

century Grand Viziers. Among the architects we know a Sargis Kala, apparently a Greek. Ibrahim also

inoled the Chie Architect Mehmet Aga, ordering him to send some o his co-workers ,laroqhi writes

junior colleagues`, to isit and study the Mustaa Pasha Mosque at Gebze ,not ar rom Istanbul, and

other mosques in western Anatolia. 1he architects were enjoined to study the aesthetic appearance o the

buildings and also construction details, bringing back drawings or the Grand Vizier's inspection. 1he

latter apparently resered or himsel the ultimate decision, and, taking an eclectic approach, consciously

modelled his oundation on the buildings put up by 10th,16th century Grand Viziers.` 1he mosque o

Mustaa Pasha at Gebze ,1519 or 1525-6, would, howeer, been quite a curious choice, as this was the

commission o an oicial rom Lgypt who had the decoration or this mosque carried out in the Mamluk

style ,c. 1aeschner 2004:982,.

21

It is probably these turrets Kuran ,19:304, had in mind when lamenting that the clarity o structural

expression slowly disintegrated because o the inclusion o superluous elements`.

23

does not possess the bold strokes o his predecessors. In a changing era he eels the

need or innoation. Inentieness, howeer, requires imagination and sel-conidence.

Lacking these, he resorts to distortion and his work becomes mannered.`

24

J.2.3. 1he Danube Principalities under Phanariote rule

In no case more than in the Romanian one, it is argued that really the eighteenth century

had brought about an Ottomanization` o Balkan territories. Beore 111 both

principalities had merely been Ottoman assals, attached to the Sultan`s domain but

retaining large autonomies. But when the relations between the \allachian and

Moldaian princes and the neighbouring Russian and Austrian empires became too

riendly or the Sultan`s taste, the preiously wide-reaching autonomies were abolished.

In 111 the untrustworthy Moldaian prince Dimitrie Cantemir, allied with Peter the

Great, was replaced with a man the Sultan could trust, Nicholas Marocordatos, son o

the Sultan`s chie interpreter ,aragovav,. In 115 the \allachian prince Stephan

Cantacuzino was executed on suspicion o league with Vienna. Both these actions led

Castellan ,1992:206, to the conclusion that the Sultan considered the rulers o the

principalities as no more than proincial goernors whom he could appoint, displace

and remoe wheneer he wished.` lenceorth the princes were appointed by the Sultan

himsel and usually recruited among the Greeks o Constantinople`s Phanari ,lener,

quarter. Between 111 and 1821 a ew mostly Constantinopolitan amilies proided no

less than 31 princes ,now called hospodars`, in 80 periods o rule, which lasted on

aerage only two and a hal years ,c. McGowan 1994:60,. laing to disburse a heay

bribe to enter this prestigious i dangerous oice, they became not hereditary rulers but

temporary Ottoman oicials. As such, as pictorial eidence o the time shows, they

dressed in the Ottoman manner, with large turbans, wearing Ottoman dress and

insignia, and a beard ,Plemmenos 2003:183,. Castellan ,1992: 20, appends that

|a|mong the lospodar`s entourage there emerged a court nobility which lied and

dressed according to the ashions o the palace o Istanbul.`

25

1he condemnation o the Phanariot era ,111-1829, has been a ocus o Romanian

nationalism and has come to be portrayed as the dark ages` o Romanian history. In

cultural terms, this is partly due to enthusiastic assessment o the preceding period, the

rule o \allachian prince Constantin Brancoeanu ,1688-114,, under which \allachian

architecture had reached its creatie peak. Brancoeanu had gien his name to a style

too eclectic to be properly categorized. It is maybe this incomprehensie hybridism -

with Baroque, Renaissance, Persian, Byzantine, Serbian, and Armenian some o the

inluences customarily mentioned - that made modern Romanians consider the

Brancoeanesque to be the only genuinely Romanian style ,c. Popescu 2004,. \ith

eidence o constant and close contact with \estern culture during the seenteenth

century ,Jelaich 1983:69,, the genesis o this style distinguished by an almost classical

equilibrium in the compositions, and by an extremely rich decoration o a baroque

taste` ,Popescu 2004:28, is oten linked to an Italian inluence. 1he Brancoeanesque,

howeer, also showed some decidedly non-\estern eatures, which Jelaich ,1983:69,

identiied as a combination o Lastern opulence with \estern reinement.` 1o Ulea

,1966:9, the principal palaces at Potlogi ,1699, and Mogosoaia ,102, |Ill.1.8|

combined 1urkish and Italian elements with traditional Rumanian orms`, with their

graceully aulted interiors . richly decorated with stucco ornament o an oriental

kind.`

O the Romanian lands \allachia had always been the region most open to eastern

inluences`, but the act that this decided orientality` is also oten linked to an actual

Ottoman inluence is debatable. 1he lobed and ogee arches o windows and arcades so

characteristic o the Brancoeanesque and post-Brancoeanesque |Ill.1.8-10|, accounting

or its exotic appearance, do generally not igure on contemporary Ottoman exteriors o

26

this period, and are most oten ound on ountains or interiors. But next to the

sumptuous palaces, the pre-Phanariote area also saw the boyars aording luxurious

mansions, a general improement o liing conditions, the blooming o monasteries and

great accomplishments in historiography ,Jelaich 1983:69,. 1hat the Phanariotes then

sought a isual continuation o this tradition in the style o religious ediices they

sponsored leads 1heodorescu ,2002:9, to suggest this as part o an attempt to make

the shit rom being an Ottoman-imposed oreign goerning lite to that o quasi-

national and dynastic ruling amilies.`

22

1he Vacaresti Monastery in Bucharest ,116-

22, and the church o the Pantelimon Monastery ,150, in the suburbs o the \alachian

capital consciously make reerences to those erected under Brancoeanu,

23

at times and

in details heaily baroquiied`, as the portal o Pantelimon ,1heodorescu 2002:80,.

1he best-known suriing monument rom this early period o Phanariote rule in the

Danube Principalities is the Staropoleos church |Ill.1.10|, erected by the Greek

Archimandrite Ioannikos ,rom. Ioanichie, between 124 and 130 in Bucharest. lor

Plemmenos ,2003:181, an epitome o Greek-Romanian co-operation during the

Phanariote era`, the right-hand choir sung in Greek while the let-hand one answered in

Romanian using the same melody. In structure otherwise not untypical or the post-

Byzantine centuries, it is the oriental` multi-lobed arches o the portico as well as the

painted exterior that makes this monument a airly unusual one. \e ind circular

recesses with painted igural representations as a belt around the monument, embedded

22

An exclusiely Christian Ottoman territory ruled by Christian Ottoman oicials, it is not too surprising

that we ind almost no mosques in present-day Romania, sae or the Dobrudja region on the Black Sea,

which ormed an integral part o Ottoman Rumelia.

23

Ulea ,1966:9, sees Vacaresti, built by the Phanariote Marocordatos as the largest eighteenth century

monastery in Southeast Lurope, and the Staropoleos church as the last important examples o the

Brancoeanan style . 1he rest o the eighteenth century is a period o decline in religious architecture.`

2

in rich egetal ornament. 1he monastery to which it belonged, sustained rom the

incomes o an inn run by the archimandrite, is not extant.

In contrast to the churches, the Phanariotes` country estates relected, according to

1heodorescu ,2002:5,, both the orientalism o Istanbul and the inluence o the

\estern rococo, just as their owners were authentic examples o western-oriental

gentlemen.` In seeral instances 1heodorescu suggests a Phanariote orientation ater

Istanbul trends o the 1ulip period. 1he lrumoasa ,the Beautiul`, complex at Iasi, or

example, was supposedly modelled ater Constantinopolitan prototypes, whereby master

builders were speciically called into the country. 1he closest analogy or the palace o

\allachia`s Gregory II, a mid-eighteenth century two-storied structure next to his

monastery, 1heodorescu beliees to hae ound in an illustration o Ahmet III`s

Sa`dabad ,122,.

24

But an eastern impact also inluenced spatial considerations, as he

suggests to hae been the case with the Moldaian prince Gregory`s palace, rebuilt twice

as large ater destruction by the Russian soldateska in 140, and with a separation o

male and emale quarters ,selamlac` and harem`,. \hile exceptionally ew structures

rom the Phanariote period suried until today, the ountains at the churches o St

Spiridon |Ill.1.11| and the Golia Monastery at Iasi, dating rom 165-6, remain as rare

materializations to inluence rom Ottoman eighteenth century modes. ,1heodorescu

2002:80-3,

Gien the insecurity o the period and the patrons` position, caught between the dream

o Byzantium and the executioner o Stambul` ,1heodorescu 2002:5,, it is still

remarkable how luxury and pleasure came to be pronounced in Phanariote \allachia

24

Disappointlingy, howeer, 1heodorescu neither proides pictorial eidence nor source material as basis

or this comparison.

28

and Moldaia, especially under two quasi-dynastic amilies, the Marocordatos and the

Ghika, arguably under the impact o the liestyle o the 1ulip Lra. Neertheless, when

the lrench traeller llachat isited the Bucharest estates o Constantine

Marocordatos

25

in 141, his assessment was as ollows:

I went to the leisure palace o the prince, which, like the prince`s |city| palace, still

reminds one o its main purposes. 1hey used to be monasteries, somewhat beautiied by

his predecessor princes. Most o our second-hand priate residences are ar better

looking and there are none in our country where the urniture is worse than here ... Just

by seeing what his residence looked like, I could hae gotten an excellent impression

about his alour, but I was able also to treasure his intelligence and heart: I was able to

discoer the artist and the man o good taste eerywhere. lis book collection was rich

and exquisite, he owned some aluable paintings, some wonderul sculptures, a lot o

deices o all kinds and seeral parts o ery unusual mechanisms brought by him rom

Germany or Lngland. I think he deseres me to praise him by saying that he was a

saant without preconceied ideas and completely impartial. le would speak all

Luropean languages and was amiliar with the most important writers whom he tried to

know as well as possible.` ,cit. in Berktay and Murgescu 2005:106,

Ottoman oicials, the Phanariote princes in Romania attempted to project the proile o

enlightened rulers. laing themseles haing been exposed to western Luropean

culture through the education which they had receied in western uniersities, it was as

early as 114 that the Moldaian prince Marocordatos ounded an Academy o Letters

in his capital Iasi, with a curriculum copying that o renowned Luropean uniersities,

but with Greek as oicial language ,Plemmenos 2003:186,. At the same time, howeer,

the Phanariotes hae been accused o not haing taken the opportunity to proide

patronage or art and learning o a kind not aailable to non-Muslims in the core

territories` o the empire, and urthermore hampering local cultural deelopment

25

One o the most enlightened Phanariote rulers, Marocordatos ,111-169, reigned six times in

\allachia and our times in Moldaia. Among the reorms he undertook was the abolishment o serdom.

29

through imposing heay taxes on their subjects to inance the appointments o the

rapidly changing hospodars ,c. Adanir and laroqhi 2002:26,. Gradea ,1994:25,,

howeer, mentions a case where a \allachian prince had acted as beneactor

transcending his own territory into an Ottoman core territory`: \ithout notiication

o, or permission rom, the Sultan he had restored and enlarged a church in Silistra ,on

the Danube, the border between \allachia and Bulgaria, in 141. Runciman ,1991:13-4,