Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Soundry

Uploaded by

DallasObserver0%(1)0% found this document useful (1 vote)

669 views9 pagesFrom a 1966 history of the Dallas Independent School District, published by the DISD on the occasion of its 92nd anniversary

Original Title

~ Soundry

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentFrom a 1966 history of the Dallas Independent School District, published by the DISD on the occasion of its 92nd anniversary

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0%(1)0% found this document useful (1 vote)

669 views9 pagesSoundry

Uploaded by

DallasObserverFrom a 1966 history of the Dallas Independent School District, published by the DISD on the occasion of its 92nd anniversary

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

1874-1966

Ninety-two Years

of History

DALLAS INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT

Ss i s AO OS

MAP OF DALLAS INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT

DALLAS, TEXAS

Revised August 1965 to Bring School locations and Designations up to date.

FOREWORD

The Public School System of Dallas, since 1947 the Dallas Independent

School District, is approaching the century mark. This book relates to most of

the important steps in the attainments, present status, and magnitude of oper-

ations of the schools. The School System will continue to expand and grow,

meeting the responsibilities of public education for the young citizens of the

community.

In time we anticipate that a second volume of Education in Dallas may

be written with a view to maintaining a current and complete history of this

great public institution.

W. T. White

VI

PART I

THE EARLY YEARS 1874-1899

Uncertainty as to Beginnings

1874-1884

CHAPTER

1

Exact times and dates of the beginning

of the Dallas Public Schools are difficult to

set, Volume I, page 1 of the Minutes of the

Board of, Education shows the inscription,

“On June 16th, 1884, in the office of R. D.

Coughanour, the Board of School Trustees

organized.” This terse statement, beautiful

in its brevity, makes a good beginning and

is amplified by the School Report of 1885

by Superintendent Boles addressed to the

“Hon. Board of Directors, Dallas Public

Schools,” which begins with the phrase, “I

herewith submit to your honorable body

the first Annual Report of the Graded Pub-

lic Schools of this City.” Succeeding reports

identify 1884-1885 as “the first year of the

Dallas Public Schools.”

This should rather neatly and nicely set

the date of June 16, 1884, as the beginning

of the Dallas Public Schools, were it not

for the Reports referring statistically to

days which went before. On July 21, 1884,

Mayor W. L. Cabell ordered “That all

former Ordinances in relation to the city

public school are hereby repealed.”

Schools of some sort existed prior to the

1884 organization. Mr. Boles, Superintend-

ent for the year 1884-1885, reports the fol-

lowing enrollment statistics

Year Enrolled

1880 1218

1881 1351

1882 1453

1883 1760

1884 2537

1885 3204

The record for the year 1883-1884

showed receipts from the County Fund

of $598.40 and from the State Fund

$7920.00 for a total of $8518.40. Further-

more, it is reported “that the city owns

six public school houses — four devoted to

white and two to colored children,” all

acquired before 1884.

Dallas was concerned with the education

of its children prior to 1884, but the depth

and substance of this concern is con-

jectural.

All references to the year 1884 appear-

ing in the Annual Report are made to the

act of “organization.” That schools existed

prior to 1884 in quasi-public form is ap-

parent, but the Dallas Directory of 1873

“regrets to say that there are no public

schools in Dallas.”

This publicity, even though adverse,

produced almost immediate results, for

the Directory of 1875 proudly proclaims

that “the schools are near perfection.”

Something happened between 1873 and

1875 to identify the year 1874 as the year

of the beginning of the public schools in

Dallas, with some reservations, perhaps,

as to the exact day and furthermore as

to the use of the word “public” as it is

understood today.

Schools in their development respond to

their social, economic, and cultural envi-

ronment. The forces of community life beat

in on the process of education and tend to

shape it. Contrariwise, the educational urge

has a strength of its own, and in its own

right beats back in an effort to condition

and shape the destiny of the community.

With mud when it rained, and dust when

drought-stricken, and with rival railroads

uniting to double the population periodi-

cally and the industrial potential, Dallas

took time to plan its schools.

When Texas “came in” in 1870, it was, in

the words of Robert T. Hill, “the darkest

field educationally in the United States.”

State legislation, reflecting the temper

of the times, produced the Constitution of

1876. This tool, tough on educationalists,

because of early and sad experiences with

visionaries, allowed but little leeway for

philosophers.

In 1877, Dallas, under the nudging of

Mayor W. L. Cabell, took advantage of

the constitutional provisions and took

charge of its public schools. Up to this

time there had been no district organiza-

tion and no public school buildings. Local

communities furnished space in churches

or Masonic Halls, whenever a teacher

might be available, “to get himself up a

school.” Tuition was the basis of the

teacher's salary, supplemented from state

funds for indigents who could not afford to

pay.

Four trustees were chosen by the City

Council, one for each of the four wards;

three examiners for teachers were ap-

pointed; and most important, a tax of one-

half of one per cent was levied for school

purposes. This made it possible to pay the

teachers by warrant, drawn by the city

secretary and signed by the mayor on

voucher of the president of the school

board. Sites and buildings were acquired

and the trustees were instructed, “to visit

the different schools at least once a month

and inspect the management of the same.”

Progress is reflected in the Dallas City

Directory of 1880, where the school board

is complimented on its zeal in the face of

“support that is little more than a pit-

tance,” as a result of which the schools

were kept only five and one-half months

of the year.

Four ward schools had been augmented

by three colored schools. In 1883, a special

tax was levied to build a free school house

in every ward. “Some of them will be

occupied before this is printed. They are

two stories, with room enough to hold

two or three hundred children.” Size and

layout of rooms were not cited by the

reporter of the article. He was thinking

in terms of “two or three hundred chil-

dren,” and in this sense he was a poet,

calling attention to dreams and hopes

rather than inches and feet.

This, then, presents the condition exist-

ing in 1883, In an environment of lively,

rugged growth, the City of Dallas had

engineered an incipient program of public

schools, similar to that developing in its

sister cities in the nation. From an original

cadre of fourteen teachers in 1877, there

had been an increase of only one teacher

by 1882, a fairly stable arrangement, one

might say, in the fact of an increase in

population from 6,000 to 18,000. ‘This pre-

sents one reason for the reorganization of

1884.

The Schools of Dallas had been operat-

ing under the State Law of 1873, which,

according to Benjamin M. Baker, State

Superintendent from 1883 to 1887, was

most unsatisfactory. At a special session

of the Eighteenth Legislature on February

6, 1884, the law was “amended and re-

written in its entirety and this revised code

breathes a new spirit and purpose.” The

law provided for a district system even to

the extent of specifying that “each District

shall be given a number which shall be

painted over the door of the school house.”

Mr. Baker identified disadvantages in

the older community system in the uncer-

tainty of annual reorganization and in the

disability of local communities to tax

themselves. “Your (new) district system

suffers none of these disadvantages, Under

it local taxes may be levied and funds

raised for building purposes, or lengthen-

ing the school term and extending the

school age. The districts have definite

limits; the place of the school is fixed...

teachers are thereby encouraged to be-

come more professional.”

Under the old law the teachers’ salaries

were dependent upon the attendance of

the pupils and “this was a relic of

barbarism.”

The Act of 1884 became a law without

the governor’s signature on February 6,

1884, and it did not take long for the

news to reach Dallas. Quite likely, Mr.

Coughanour and his group, expert in legal

matters, sensed the importance of the act

and acted immediately to take advantage

thereof, even to the extent of calling a

meeting on a Sunday afternoon, “to organ-

ize.” By the time watermelons were ripe,

they had elected a superintendent and

induced the Dallas City Council to grant

them authority to operate a public school

system worthy of the name.

This was the year, 1884, when Grover

Cleveland was elected president of the

United States, with the help of the

“Mug-Wumps.”

: Bit linaen

- heerclary

OR, Bont, .

Dyer

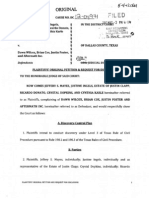

Minutes of the First Meeting, June 16, 1884

A Forward Look

CHAPTER

V4

This chapter might be termed a brief

halt to consider the advyancéd position of

the Dallas Independent School District and

to recomnoiter the next move.

The past history of the Dallas Public

Schools shows a process of closing of gaps

between theory and practice. Educational

leadership was ever active in striving for

the best interests of the individual child

and in making pronouncements thereof in

terms of theoretical considerations, but it

took time to put these pronouncements

into practice.

‘The future appears explicit in this same

context. What has happened will continue

to happen, more so or less so. There will

continue a closing of gaps between theory

and practice, as the schools catch up with

their dreams, but trouble is in the offing

as new dreamers, insisting on being heard,

create new gaps in other places as the old

gaps are closing.

The backward look shows attempts to

struggle with the fact that some children

were not in school and were not getting

the benefits from free public education.

Various attempts are seen in the years gone

by to.remedy the situation. Truant officers

belabored their trust and did some good.

Compulsory attendance laws were passed,

never with teeth enough to bite. The belief

that the father had a right to his child’s

labor in maintaining the home and keeping

body and soul together was stretched to

include a car and other necessities and

would not down.

219

Principals coaxed and coached their con-

stituency and walked over hill and dale in

an effort to catch up with their wander-

ing boys and girls, but “moral 'suasion”

was their big power.

The present law requires pupils to attend

school until their sixteenth birthday, Soon

this will be changed to their seventeenth

birthday, and with a changed feeling on

the part of the public it will be possible to

file complaints against the child and his

parents in case of carelessness. It is not

pleasant to contemplate filing, but when

the law says that something shall be done,

the unpleasantness of the deed will not be

a governing factor forever. Quite likely,

with the mounting cost of education, there

will be a mounting effort to make educa-

tion more effective in the lives of the people

who disregard the law.

Statistics

The enrollment follows a straight line

on the graph for the years 1960-65 and this

line projected indicates enrollment in 1970

at 180,000 and in 1975 at 205,000. The in-

crease in the number of schools to accomo-

date this increase of enrollment would be

fifty schools. Taking into consideration the

reduction shown in the national birth rate

since 1957, it is quite likely that these fig-

ures will not be attained. The annexation

program for the next decade will be a

governing factor. If the rate of increase in

enrollment for the past five years were

reduced one half for the next five years,

opportunity for education has gathered

and has fanned out to include the high

academic classes with advanced college

credit possibilities on one edge of the spec-

trum to the classes in simple skill training

for the barely educable at the other. Music,

art and physical education have gathered

force as they roll along.

Teaching aids are here to stay and will

be watched for possible improvement and

extension, Television, radio, tape recorders,

record players, and Ianguage laboratories

will enrich and expand the curriculum in

professional growth programs for teachers.

Data processing has taken hold and will

find many uses not now'contemplated, even

to the point of aiding in the development

of local school or class action-research

programs.

The culmination of eighty years of steady

striving on the part of school boards and

superintendents for improved teaching is

seen in the professional improvement pro-

gram now operating under the title of

“Toward Instructional Excellence.” This

will continue to grow in popularity and

effectiveness as its advantages are felt.

The educational specialist has demon-

strated his value in terms of expert service

to the teachers and to the establishment

and maintenance of an organismic charac-

ter of the curriculum in the face of many

atomizing influences. His tribe will in-

crease.

Data processing machinery will serve to

give adequate attention to better guidance

procedures in that the distribution of pupils

per class will be accommodated to the

pupils’ needs rather than, as in the past,

to the classes which happened to be avail-

able at a given period and which needed

“filling up.” This will be especially true in

the cases of such fields as physical educa-

tion and health instruction. Classes will be

assigned pupils according to their calcu-

221

lated needs, rather than pupils assigned

to classes for the sake of administrative

details. The two reasons will more nearly

become one as the use of data processing

machinery expedites the better use of

school facilities.

Special education programs will con-

tinue to expand. “This is not a closed

circuit. Additional programs will become

a part of this operation as educators try

out and develop additional benefits to be

derived from the instruction,”*

‘The year 1964-65 gave more than a hint

of things to come. The Language Arts Cur-

riculum Guides, showing signs of wear and

tear, indicate an impending revision in the

light of the linguistic science and the study

of people as revealed in their languages,

without loss of skill in grammar and com-

position. The application of electronic

devices to this purpose in the language

laboratories testifies -to the generalization

of education as it operates in the broad

fields organization.

Mathematics will continue “new” and

perhaps get worn in. The boys and girls

in the filth grades may continue to have

some dislike for it, but the children in the

first grades will get along fine.

The proposed goal in mathematics in-

cludes the involvement of the pupils with

much more mathematics than at present:

the introduction of more mathematics in

the elementary school and the speeding up

of the seventh and eighth grades, the re-

evaluation and reorganization of content

all along the line, and finally more stimu-

lating and efficacious pedagogy.

Federally subsidized research programs

summarized by the American Educational

Research Association show which way the

winds are blowing in Washington and pres-

ent a criterion for evaluating local interest.

Activities such as education of handicapped

‘White, W. T., Special Fdecation, Dallas Tndepeadeat School

District, 1905

children, language development, com-

munity action, vocational rehabilitation,

prevention and reduction of poverty and

dependency, mental health with respect to

early detection of emotional disorders and

Dehavorial problems, major _ problems

in education, curriculum improvement

through use of new techniques and ma-

terials, improvement of teaching-learning

process through media within the instruc-

tional context, child welfare, help for the

labor force to acquire new knowledge and

skills necessary to the nation’s economy,

and improvement of the courses in mathe-

matics and science, may receive help for

research and development.

‘This is what is “in transit” experimentally

on the national level and presents a fore-

cast of things to come.

“We'd rather do it ourselves” is a phrase

which has been representative of local

philosophy down through the years, and

this may continue as something more than

vestigial. However, some increase in col-

laboration with State and Federal Agen-

cies of Education may result from the in-

creased richness of forthcoming financial

subsidies, particularly in the area of re-

search.

Science Development

The school system is on the verge of

having available more practical and useful

scientific information than any school dis-

trict imagined having, according to Super-

intendent W. T. White. With the advances

in space exploration and other scientific

and mathematical fields, new techniques

in teaching and new concepts in education

are spreading down through the grade sys-

tem and through the clementary school as

low as the first grade.

Just as a wandering minstrel, shading

his eyes against the shining Camelot, might

have asked, “Who and wherefore?” so a

newcomer to Dallas, upon perceiving this

sprawling city with its 174 school buildings,

its 5,555 teachers and principals, its 155,-

000 pupils, its annual budget of $75,000,-

000.00, might ask a similar query concern-

ing so vast a plan and find the answer in

the Apocrypha: “Consider that I labored

not for myself only, but for all them that

seek learning.”

‘An Open and Closed Case.

You might also like

- Wilfred Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, Wilfred Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 445 F.2d 990, 10th Cir. (1971)Document25 pagesWilfred Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, Wilfred Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 445 F.2d 990, 10th Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Swann V. Charlotte MecklenbergDocument22 pagesSwann V. Charlotte MecklenbergGeorge ConkNo ratings yet

- School Architecture - Containing Articles And Illustrations On School Grounds, Houses, Out-Buildings, Heating, Ventilation, School Decoration, Furniture, And FixturesFrom EverandSchool Architecture - Containing Articles And Illustrations On School Grounds, Houses, Out-Buildings, Heating, Ventilation, School Decoration, Furniture, And FixturesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Ryerson Memorial Volume: Prepared on the occasion of the unveiling of the Ryerson statute in the grounds of the Education department on the Queen's birthday, 1889From EverandRyerson Memorial Volume: Prepared on the occasion of the unveiling of the Ryerson statute in the grounds of the Education department on the Queen's birthday, 1889No ratings yet

- The History of University Education in Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University (1876-1891). With supplementary notes on university extension and the university of the futureFrom EverandThe History of University Education in Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University (1876-1891). With supplementary notes on university extension and the university of the futureNo ratings yet

- The Louisiana School for Math, Science, and the Arts: The First 30 YearsFrom EverandThe Louisiana School for Math, Science, and the Arts: The First 30 YearsNo ratings yet

- Looking Back: A Journey Through the Pages of the Keowee CourierFrom EverandLooking Back: A Journey Through the Pages of the Keowee CourierNo ratings yet

- Chaptee: AdvancementDocument17 pagesChaptee: AdvancementRussell HartillNo ratings yet

- The History of University Education in Maryland The Johns Hopkins University (1876-1891). With supplementary notes on university extension and the university of the futureFrom EverandThe History of University Education in Maryland The Johns Hopkins University (1876-1891). With supplementary notes on university extension and the university of the futureNo ratings yet

- Schooling the New South: Pedagogy, Self, and Society in North Carolina, 1880-1920From EverandSchooling the New South: Pedagogy, Self, and Society in North Carolina, 1880-1920Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Pillars of the Republic: Common Schools and American Society, 1780-1860From EverandPillars of the Republic: Common Schools and American Society, 1780-1860Rating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (3)

- The Common School Movement in ColoradoDocument3 pagesThe Common School Movement in ColoradodennispolhillNo ratings yet

- Superintendent (Education)Document2 pagesSuperintendent (Education)hurlyhutyoNo ratings yet

- Charter School City: What the End of Traditional Public Schools in New Orleans Means for American EducationFrom EverandCharter School City: What the End of Traditional Public Schools in New Orleans Means for American EducationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Making a Mass Institution: Indianapolis and the American High SchoolFrom EverandMaking a Mass Institution: Indianapolis and the American High SchoolNo ratings yet

- Blaming Teachers: Professionalization Policies and the Failure of Reform in American HistoryFrom EverandBlaming Teachers: Professionalization Policies and the Failure of Reform in American HistoryNo ratings yet

- Education Time Line 1Document5 pagesEducation Time Line 1api-635562745No ratings yet

- Money and School Performance: Lessons From The Kansas City Desegregation Experiment, Cato Policy AnalysisDocument35 pagesMoney and School Performance: Lessons From The Kansas City Desegregation Experiment, Cato Policy AnalysisCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- Newark's Last Fifteen Years, 1904-1919. The Story in OutlineFrom EverandNewark's Last Fifteen Years, 1904-1919. The Story in OutlineNo ratings yet

- Hope Against Hope: Three Schools, One City, and the Struggle to Educate America’s ChildrenFrom EverandHope Against Hope: Three Schools, One City, and the Struggle to Educate America’s ChildrenRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Writing Their Bodies: Restoring Rhetorical Relations at the Carlisle Indian SchoolFrom EverandWriting Their Bodies: Restoring Rhetorical Relations at the Carlisle Indian SchoolNo ratings yet

- Brian Miller - EN - American Residential Schools For The Blind and The Limits of ResistanceDocument17 pagesBrian Miller - EN - American Residential Schools For The Blind and The Limits of ResistanceFondation Singer-PolignacNo ratings yet

- The Choctaw Freedmen and the Story of Oak Hill Industrial AcademyFrom EverandThe Choctaw Freedmen and the Story of Oak Hill Industrial AcademyNo ratings yet

- ThesispaperquinneyDocument9 pagesThesispaperquinneyapi-276980229No ratings yet

- Elements of Civil Government: A Text-Book for Use in Public Schools, High Schools and Normal Schools and a Manual of Reference for TeachersFrom EverandElements of Civil Government: A Text-Book for Use in Public Schools, High Schools and Normal Schools and a Manual of Reference for TeachersNo ratings yet

- Education TimelineDocument7 pagesEducation Timelineapi-534435391No ratings yet

- Book Item 40635Document21 pagesBook Item 40635JOSEPH PAPELLIRONo ratings yet

- EDLD7431 Field ObservationDocument7 pagesEDLD7431 Field ObservationAlma YoungNo ratings yet

- The Autobiography of Citizenship: Assimilation and Resistance in U.S. EducationFrom EverandThe Autobiography of Citizenship: Assimilation and Resistance in U.S. EducationNo ratings yet

- Educational Timeline 1600-2000sDocument5 pagesEducational Timeline 1600-2000sapi-340723688No ratings yet

- Artifact 1Document5 pagesArtifact 1api-357533670No ratings yet

- Child Labor in Greater Boston: 1880-1920From EverandChild Labor in Greater Boston: 1880-1920Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Patty J - Historical Events in Higher EducationDocument14 pagesPatty J - Historical Events in Higher Educationapi-296418803No ratings yet

- Why Public Schools? Whose Public Schools?: What Early Communities Have To Tell UsFrom EverandWhy Public Schools? Whose Public Schools?: What Early Communities Have To Tell UsNo ratings yet

- All Deliberate Speed: Segregation and Exclusion in California Schools, 1855-1975From EverandAll Deliberate Speed: Segregation and Exclusion in California Schools, 1855-1975No ratings yet

- Neglected Vagrant and Viciously Inclined The Girls of The Connecticut Industrial SchoolsDocument135 pagesNeglected Vagrant and Viciously Inclined The Girls of The Connecticut Industrial Schoolsphdt10% (1)

- 1931 YearbookDocument47 pages1931 YearbookHarbor Springs Area Historical Society100% (1)

- The Feds Say They Shut Down Nine Massage-Parlor Brothels in Massive Prostitution BustDocument19 pagesThe Feds Say They Shut Down Nine Massage-Parlor Brothels in Massive Prostitution BustDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Hunt TimelineDocument35 pagesHunt TimelineDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Texas On The Brink 2013Document32 pagesTexas On The Brink 2013DallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Black Nonbelievers of Dallas Press ReleaseDocument1 pageBlack Nonbelievers of Dallas Press ReleaseDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- WNV in Texas Final ReportDocument35 pagesWNV in Texas Final Reportjmartin4800No ratings yet

- Dallas Water Billing MemoDocument1 pageDallas Water Billing MemoDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Texas Freedom NetworkDocument21 pagesTexas Freedom NetworkDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Texas Freedom NetworkDocument21 pagesTexas Freedom NetworkDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Museum Tower Homeowner LetterDocument4 pagesMuseum Tower Homeowner LettercityhallblogNo ratings yet

- DSHS Family Planning MemoDocument11 pagesDSHS Family Planning MemoDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Statement On Jeffries Street Encampment From Crisis InterventionDocument2 pagesStatement On Jeffries Street Encampment From Crisis InterventionDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Barrett Brown 1/23/13 IndictmentDocument4 pagesBarrett Brown 1/23/13 IndictmentDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Time To Go Op Ed Final 10-12-12Document2 pagesTime To Go Op Ed Final 10-12-12DallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Richard Malouf Complaint and TRO Against WFAA and Candy EvansDocument79 pagesRichard Malouf Complaint and TRO Against WFAA and Candy EvansDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Trammell Crow LawsuitDocument11 pagesTrammell Crow LawsuitDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Rick Perry Deferred Action Letter To Greg AbbottDocument1 pageRick Perry Deferred Action Letter To Greg AbbottDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Museum Tower Letter To DallasDocument1 pageMuseum Tower Letter To DallasRobert WilonskyNo ratings yet

- Sandra Crenshaw IndictmentDocument1 pageSandra Crenshaw IndictmentDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- John Jay Myers FCC ComplaintDocument4 pagesJohn Jay Myers FCC ComplaintRobert WilonskyNo ratings yet

- Dallas Police and Fire Pension System, Complaint in Lawsuit Against AGDocument10 pagesDallas Police and Fire Pension System, Complaint in Lawsuit Against AGDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Aftermath CounterclaimDocument35 pagesAftermath CounterclaimDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- James Harper Gunshot Wounds, ME ReportDocument2 pagesJames Harper Gunshot Wounds, ME ReportDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Attorney General's Letter With New HHSC Guidelines On Texas-Run WHPDocument17 pagesAttorney General's Letter With New HHSC Guidelines On Texas-Run WHPDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Eccie ComplaintDocument11 pagesEccie ComplaintDallasObserver0% (1)

- American Humanists Letter To The Angelika PlanoDocument2 pagesAmerican Humanists Letter To The Angelika PlanoDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Fake Mass Grave ComplaintDocument19 pagesFake Mass Grave ComplaintDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Civil Lawsuit Against Aftermath Inc. Cleaning CrewDocument14 pagesCivil Lawsuit Against Aftermath Inc. Cleaning CrewDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Dallas Homelessness ReportDocument40 pagesDallas Homelessness ReportThe Dallas Morning NewsNo ratings yet

- Office of The Police Monitor (Dallas) Petition FormDocument1 pageOffice of The Police Monitor (Dallas) Petition FormDallasObserverNo ratings yet

- Response To Atlanta Journal ConstitutionDocument1 pageResponse To Atlanta Journal ConstitutionDallasObserverNo ratings yet