Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Effect of Consumers Mood On Advertising Effectiveness

Uploaded by

Azilmi Lukmanul HakimOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Effect of Consumers Mood On Advertising Effectiveness

Uploaded by

Azilmi Lukmanul HakimCopyright:

Available Formats

Europes Journal of Psychology 4/2009, pp. 118-127 www.ejop.

org

Effect of Consumers Mood on Advertising Effectiveness

Ademola B. Owolabi, Ph.D.

Department of Psychology, University of Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria

Abstract It is a fact that mood-state knowledge is of particular relevance for the understanding of consumer behavior. The belief that it may be affected by the content of marketing communication and the context in which these communications appear was the basis upon which this research was conducted. This study is essentially an experimental study where a between-subject design was employed. A total of three hundred and twenty subjects were used in the experiment. Unlike some previous advertising research (e.g. Kim and Biocca, 1997) utilizing existing adverts, specifically design adverts were made for the study. Standardized 10 minute film clips were used to induce a negative or positive mood. Two scales - attitude towards using advertised products and intention to try advertised products - were employed to measure advertising effectiveness. The result revealed that subjects in the induced positive mood group have a more positive attitude and greater intention to try advertised products when compared with subjects in the induced negative mood group. This suggests that advertisers should present adverts in a context that elicits happiness. Key Words: induced affect; consumer attitude; intention; positive affect; negative affect

Introduction

Individuals often try to anticipate each others mood prior to interactions and read others moods during encounters. In these ways, mood information is acquired and used informally for social and professional interactions. For example, knowledge of the bosss mood on a particular day may help an employee anticipate the bosss reactions to a request for a pay raise. Analogously, knowledge of the consumers mood state in certain situations may provide marketers and advertisers with a more complete understanding of consumers and their reactions to marketing strategies and adverts.

Effect of Consumers Mood on Advertising Effectiveness

This mood-state knowledge may be particularly relevant for understanding consumer behaviour as affected by the content of marketing communications and adverts and the context in which these communications appear. Advertising typically has some positive or negative content that can trigger affective reactions (Coulter 1998). Early research on mood and persuasion indicated that people who are in a positive mood are more susceptible to persuasion than the average person. For example, Janis (1965) had some people read a persuasive message while they ate a snack and drank soda, while others simply read the message without the accompanying treats. Greater attitude changes occurred among the munchers than among the food free group. Similar effects were also found among people listening to pleasant music (McMillan and Huang, 2002). Good feelings enhance persuasion partly by enhancing positive thinking. In a good mood, people view the world through rose-coloured glasses. They also make faster, more impulsive decisions, they rely less on systematic thinking, but more on heuristic cues (Schwarx, 1991; Garner, 2004). Because unhappy people ruminate more before reacting, they are less easily swayed by weak arguments. Thus, it has been suggested that if you cannot make a strong case, it is a smart idea to put your audience in a good mood and hope they will feel good about your message without thinking too much about it (Schwarz, 1990). One of the reasons for this, is proposed by the feelings-as-information view, that while negative moods signal to people that something is wrong in their environment and that some action is necessary, positive moods have the opposite effect; they signal that everything is fine and no effortful thought is necessary (Schawtz, 1990). As a result, people in a positive mood are more persuadable because they are less likely to engage in extensive thinking of the presented arguments than those in a neutral or negative mood. Although the feelings-as-information view contends that happy people tend to rely on peripheral route processing, an alterative cognitive response explanation the hedonic contingency view asserts that this is not always the case (Wenger and Petty, 1994). According to this perspective, happy people will engage in a cognitive task that allow them to remain happy and will avoid those tasks that lower their mood. Research investigating this possible effect indicated that a happy mood can indeed lead to greater message elaboration than a neutral or sad mood, when the persuasive message is either uplifting or not mood threatening (mood congruent) (Norris, Colmon and Aleixo, 2003; Coulter, 2003; Wegner, Petty and Smith, 1995). Thus,

119

Europes Journal of Psychology

it appears that happy people do not always process information less than neutral or sad people. Taken together, the above studies suggest that there is a likelihood that mood has a lot of effect on the way messages are received and processed. Therefore the aim of this study is to determine whether being in a positive mood or negative mood affect audience evaluation of advertisement as effective or not effective.

Materials and Methods

Design A between-subject experimental design was employed to test whether positive or negative affect induced by the film clips had any effect on advertising effectiveness. Advertising effectiveness was measured by attitude towards the advertised products scale and intention to buy the advertised products scale. The adverts were embedded into the positive and negative film clips. Setting Two laboratories in the Department of Geography and Planning Science, Faculty of the Social Science, University of Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State were used for the study, because of their quiet situation which allowed for a carefully controlled environment. Subjects The research participants were three hundred and twenty (320) university undergraduates drawn from the Faculty of the Social Science. Like most other advertising research studies (e.g. Knoch and McCarthy, 2004; Fieldling et al, 2006; Shenge, 2003; Morison et al, 2003) this study was conducted using undergraduate students, but, unlike those studies, the participants were not paid for participating in the research; neither did they receive any credit on any course for their participation. Materials The adverstiments. Unlike some previous advertising research (e.g., Kim and Biocca, 1997; Knap and Hall, 2006; Puccinelli, 2006), utilizing existing adverts, specifically designed adverts

120

Effect of Consumers Mood on Advertising Effectiveness

were used for this study. Two undergraduate actors (male and female) recruited through theatre organizations on a university campus served as the presenter of the adverts. Before video taping the adverts for each product, the actors memorized the product descriptions. Each person presented the two products to eliminate the likely effect of sex of the advert presenter. Participants mood manipulation A 10-minute film clip was used to induce a negative or positive mood. Both the negative clip and the positive clip were extracts from a home video titled The Bastard. The positive clip was about a family that everything was going on well for; the parents were prospering economically and in other respects, and the children were gaining admission into university. The negative aspect was how a gang of armed robbers came to wipe off the joy of the family by raping the daughter, killing the father and son and leaving the mother and daughter with psychologically traumatised. Extracting both positive and negative induced aspects from the same film made it possible to use the same set of actors. The two clips were subjected to a rating by a conference of experts with raters expressing 100 percent rating for the sadness-eliciting clip and 70.5 percent rating for the happiness-eliciting clip. Another set of 20 undergraduates also watched and rated the clips on a ten-point scale; a reported feeling of sadness at 9.5 was recorded for the sadness eliciting clip and a happy feeling of 8.0 was recorded for the happiness eliciting clip. These mood-eliciting clips were combined with four types of advert to produce eight adverts and affect types. Psychological instruments Attitude towards using advertised product was measured using a modified form of Belchs Semantic Differential Scale (1981) measuring attitude towards using advertised products. For reliability, Attitude Toward using Advertised Product Scale had a standardized coefficient alpha of 0.81, coefficient alpha for part 1 (five-item) split-half alpha of 0.65, coefficient alpha for part 2 (five-item) split-half of 0.68, split-half of 0.74 and overall reliability (Spearman-Brown) coefficient of 0.85 (Shenge, 2003). For validity, there was a least correlated item-total correlation of 0.36 and a highest correlated item-total correlation of 0.61.

121

Europes Journal of Psychology

Intention to try advertised product was measured using a ten-item set of opposite-inmeaning evaluative factor adjectives earlier used by Shenge (1996). It measures subjects intention to try the advertised product, which in real life advert practice, is also viewed by the advertiser as instrumental for unticipating the audiences final purchase of the advertised product. For reliability, the Intention To Try Advertised Product Scale had a standardized coefficient alpha of 0.75, coefficient alpha for part 1 (five-items) split-half coefficient alpha of 0.61 for part 2 (five-items) split-half of 0.57, split-half of 0.62 and overall reliability (Spearman-Brown) coefficient of 0.77. For validity, there was a least correlated item-total correlation of 0.33 and a highest correlated item-total correlation of 0.48; also, a factor analysis result on intention showed that there was a high degree of agreement among the intention scale items (Shenge, 2003). Procedure Prior to the participants admittance to the laboratory, efforts were made to minimize distraction by lowering the window blind. Efforts were also made to prevent passers-by from making a noise and distracting the subjects. Participants were randomly assigned to the various experimental groups. After the instruction was given participants watched the film clips assigned to them. Participants were not told the relevance of the film clips to the adverts. At the end of the exercise, they rated their feelings about the adverts using the questionnaire given to them. The completed questionnaires were collected and participants were debriefed, thanked and politely sent away.

Results

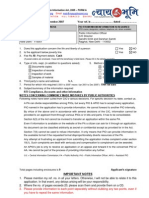

Table of mean scores on advertising effectiveness as determined by sex of advert presenter, product type and mood

Sex of advert presenter Male 39.61 female 40.99 Product type masculine 41.16 feminine 40.05 Mood positive 44.50 negative 32.05

122

Effect of Consumers Mood on Advertising Effectiveness

A summary of 2x2x2 ANOVA table: showing the effect of Sex of Advert Presenter, Product Type and Mood on Advertising Effectiveness.

Source S. A. P (A) Product type (B) mood (C) AXB AXC BXC Error Total SS 126.920 333.869 570.249 38.934 36.475 108.631 19020.135 612722.00 df 1 1 1 1 1 1 288 319 MS 126.920 333.869 570.249 38.984 36.476 108.631 66.04 F 1.92 2.05 8.36 0.59 0.55 1.64 P NS NS .05 NS NS NS

*S A P = Sex of advert presenter

The results revealed that induced affect had a significant effect on advertising effectiveness (F (1, 318) = 8.36, P< .05). An observation of the mean score shows that participants in the happy mood have a more positive attitude towards the advertised product (x = 44.50) as compared to participants in the sad mood (x 32.05). This finding concurs with Schwarz and Clores (1988) findings that customers will often use their feelings as information and, therefore, make judgment that are congruent with the implications of these feelings.

Summary and discussion

This study experimentally examines the effects of mood on advertising effectiveness. Sex of advert presenter and product types were build into the study to control for the possible effect that they may have on the study. Positive and negative mood were induced with the use of home video. In measuring advertising effectiveness two criteria were combined: attitude towards advertised product and intention to try advertised product. Belch (1981), Cacioppo and Petty (1974), and Schroeder (2006) have found that multiple criteria were more efficacious in measuring of advertising effectiveness than a single criterion. The findings reveals that there is a significant effect of mood on advertising effectiveness, but there are no significant effects of sex of advert presenter and product type on advertising effectiveness Wegener & Braverman (2004) provided evidence that people who are in a good mood like adverts more and are more capable and willing to process message

123

Europes Journal of Psychology

information. This means that when people are in good mood they view the world through rose-coloured glasses and evaluate events around them positively (Garsper, 2004). Various mechanisms have been proposed to explain this phenomenon. According to the excitation or affect transfer hypothesis (Cantor, Zillman and Bryant 1975, Tavassoli, Shuitz and Fitzsimons 1995), the positive evaluation of the context is transferred to the advert and, as a result, the advert is also positively evaluated. Another explanation is the fact that a positive mood enhances advert processing according to the hedonistic contingency theory (e.g. Lee and Sternthal, 1999). People in a positive mood engage in greater processing of stimulus because they believe that the consequences are going to be favourable. This explanation is similar to that advanced by Isen (1984) who stated that knowledge structure (associative networks) associated with good moods are generally more extensive and better integrated than structures that are associated with bad moods (affective priming). Aylesworth and Mackenzie (1998) provided a different explanation for the same phenomenon. They established that television advert processing is better when people were in a positive mood after seeing a programme. Their explanation is that people who are in a bad mood after seeing a programme are still processing the programme centrally while seeing the advert, as a result of which the advert is processed peripherally. People who are in good mood after seeing a programme are less inclined to analyse it further, and, therefore, are more capable of processing the advert centrally. As a result, a media context that is well appreciated may lead to a more positive appreciation of the advert shown in that context and to more elaborate advert processing. The excitation transfer hypothesis and related theories have been confirmed in several other studies (Goldberg and Gorn, 1987; Murry, Lastovicka and Singh 1992; Lynch and Stipp, 1999). The finding of this research lends credence to Puccinelis (2006) findings that participants in a good mood react positively to a salesperson who conveys positive feelings and are willing to pay more for the product endorsed by the person, while participants who are in a bad mood react negatively to such a person and are willing to pay less for the product. This finding contradicts some studies that concluded that a positive mood does not lead to positive evaluation of advert, e.g., Cantor and Venus (1980), Derks and Avora (1993). In their findings, using the contrast effect of Mayers Levy and Tybount (1997), they assert that message style that contrasts with the nature of the context may lead to positive advertising effects.

124

Effect of Consumers Mood on Advertising Effectiveness

The study suggested that a positively evaluated environmental context, or a context that evokes a positive mood, leads to a less positive advert evaluation and especially less advert processing. This phenomenon is attributed to the fact that a positive mood reduces the processing of stimulus information. According to the cognitive capacity theory, a positive mood activates an array of information in the memory that limits the recipients processing of incoming information (Mackie and Worth, 1989). It is worth noting that for an advert to achieve the desired aim of creating a favourable impression in the mind of the audience it seems to be useful if members of the audience are in a happy mood.

References

Aylesworh, A. B; and Mackenzie, S. B. (1998) Context is Key: The effect of program induced mood on thoughts about ad. Journal of Advertising, 27 (2), 7-27. Belch, G. E. (1981) An examination of comparative and non-comparative Television Commercial: The effects of clean variation and repetition on cognitive response and message acceptance. Journal of Marketing, 28, 333-348. Bless, H, Clore, G .L, Schwarz, N, Golisano, V, Rave C., and Work, R (1996) Mood and the use of scripts. Does being in a happy mood rely lead to mindlessness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Bless, H, Mackie, D. M and Schwarz, N (1992) Mood effects on encoding of judgmental processes in persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 58-595. Cantor, J. R. and Venus, P (1980) The effect of humour on recall of a Radio advertisement Journal of Broadcasting, 24 (1), 13-22. Cantor, J. R; Zillman, D and Bryant J. (1975) Enhancements of humour appreciation by transfer excitation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32, 69-75. Coulter K. S. (1998) The effects of affective responses to media context on advertising evaluations, Journals of Advertising, 27 (4), 41-51. Fielding, S; Hundley, M; Reid, G. and Whitehad, H. (2006) The effect of screen size and audience size on impressions of personal space when watching television.

125

Europes Journal of Psychology Gardner, M. (2004) Mood states and consumer behaviour: A critical review Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 12, 281-300. Gasper, K. (2004) Do you see what I see? Affect and visual Information processing. Cognition and Emotion, 18(3), 405-421. Goldberg, M. E. and Gorn, G. J. (1987) Happy and sad T. V. program: How they affect reactions to commercials Journal of Consumer Research, 14 (December), 387-403. Isen, A. M and Daubman, K. A (1984) The influence of affect on categorization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1206-1217. Janis, I. L. (1965) Facilitating effects of eating while-reading on responsiveness to persuasive communications. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology ,1, 181-186. Kim, T. and Biocca (1997) Telepresence via television: Two dimensions of telepresence may have different connecting to memory and persuasion; Journal of Computer Mediated Communication. 3 (2) pp 600-613. Knap, M. L. and Hall, J. A. (2006) Non-verbal communication in human interaction (6th eds) Belmont. Thomson Wadsworth. Knoche, H. and McCarthy, J. (2004) Mobile users needs and expectations of future multimedia services in proceedings of the WWRF 12. Mackie, D. M. & Worth, L. T (1989) Cognitive deficits and the mediated role of positive affect in persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57, 101-122. McMillan, S.J and Huang, J.S (2002) Measures of perceived interactivity: An exploration of the role of direction of communication, user control and time in shaping perceptions of interactivity, Journal of Advertising 31, 3, 29-42. Puccineli, N. M; (2006) The impact of customer mood on salesperson evaluation. Journal of Consumer Research, 48, (2), 39-54. Schwarz, N and Clore, G. L (1996) Feelings and phenomenal experience. In Higgins and Kruglanski (Eds), Social Psychology; Handbook of Basic Principle. New york: Guilford. Schwarz, N, (1990) Feelings as information: information and motivational functions of affective states. In E. T Higgins (Eds) and cognition: Formations of Social Behaviour (vol 2, 527-561) a New York, Guilford press.

126

Effect of Consumers Mood on Advertising Effectiveness Schwarz, N, Bless, H., Bohner, G (1991) Mood and persuasive communications. In M. Zanna (Education) Theories in Experimental Social Psychology vol. 24, 161-199, San Diego, CA: Academy Press. Shenge, N. A. (1996) An experimental study of persuasive mechanisms and the impact on television commercial efficacy. An unpublished M. Sc Dissertation submitted to the department of Psychology, University of Ibadan. Shenge, N. A. (2003) An evaluation of pressure response and active learning advertising theories on efficacy of television commercial messages: An unpublished Doctoral thesis submitted to the department of Psychology, University of Ibadan.

Wagener, D. T., Petty, R. E and Smith, S.M (1995) Positive mood can in crease or decrease message scrutiny. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69 132- 147. Wegener, D. T and Petty, R. E. (2001) understanding effect of mood through the elaboration like hood and flexible correction models. In. L.L. Martin and G. L. Clore (eds). Theories of mood and cognition: A Users Guild Book (pp.177-210) Worth, L. T. and Mackie, D. M (1987) Cognitive mediation of positive persuasion. Social Cognitive, 5, 76-94. Zillmann, D (1988a) Mood management through communication choices. American Behavioral Scientist, 31 (3), 327-341. Zillmann, D (1988b) Mood management. Using entertainment to full advantage. In L Donohew, H. E Sypher, and E. T Higgins (Eds), Communication social cognition and affect (147-171). Hillsdale, N. J Lawrence Erilbaum Associates. Zillmann, D (2000) Mood Management in the context of selective exposure theory. In M.F Roloff (Education), Communication yearbook 23 (103-23) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

About the author:

Dr A. B Owolabi is a lecturer in the Department of Psychology, University of Ado Ekiti Nigeria. He is an industrial/organizational Psychologist with an interest in consumer behavior and Psychology of advertising. He has published several articles in this area. All correspondence should be address to; Owolabi A. B, Department of Psychology, University of Ado Ekiti, Nigeria, P. m. b 5363 E-mail: labdem2005@yahoo.ca

127

You might also like

- The Effect of Appeal Type and Gender On The Effectiveness of Scotch Tape Advertising by James DuongDocument10 pagesThe Effect of Appeal Type and Gender On The Effectiveness of Scotch Tape Advertising by James DuongJames DuongNo ratings yet

- Mind Magic: Building a Foundation for Emotional Well-BeingFrom EverandMind Magic: Building a Foundation for Emotional Well-BeingNo ratings yet

- SOPHIADocument41 pagesSOPHIAEla GiurgeaNo ratings yet

- Non Recognition of Print Advertising Emotion Arousal and Gender EffectsDocument20 pagesNon Recognition of Print Advertising Emotion Arousal and Gender EffectsRameesha NomanNo ratings yet

- tmpF1C8 TMPDocument6 pagestmpF1C8 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Walker Effects of Sexualization in AdvertisementsDocument37 pagesWalker Effects of Sexualization in AdvertisementshardikgosaiNo ratings yet

- Emotional or Rational The Determination PDFDocument24 pagesEmotional or Rational The Determination PDFShazia AllauddinNo ratings yet

- The Roles of Emotion in Consumer ResearchDocument9 pagesThe Roles of Emotion in Consumer Researchm_taufiqhidayat489No ratings yet

- Business Research Assignment - 1: Submitted By: Fajer Abdul Malik - Emba/8053/12Document5 pagesBusiness Research Assignment - 1: Submitted By: Fajer Abdul Malik - Emba/8053/12Arun MohanNo ratings yet

- ResearchproposalDocument4 pagesResearchproposalapi-312630115No ratings yet

- New & Existing BrandDocument17 pagesNew & Existing Brandkashif salmanNo ratings yet

- Balaterobalaso Bookbind Bsba MM ResDocument14 pagesBalaterobalaso Bookbind Bsba MM Resjatzen acloNo ratings yet

- Graham, David and Paul, 2013Document26 pagesGraham, David and Paul, 2013Farhat AliNo ratings yet

- Gender & Mood Effects On GenderDocument25 pagesGender & Mood Effects On GenderNikita HuddartNo ratings yet

- Use of Future Projection Technique As Motivation Enhancement Tool For Substance Abuse TreatmentDocument15 pagesUse of Future Projection Technique As Motivation Enhancement Tool For Substance Abuse TreatmentJelena MitrovićNo ratings yet

- Intervention ProtocolDocument6 pagesIntervention Protocolapi-383927705No ratings yet

- Effects of Sexual Advertising On Customer Buying DecisionsDocument7 pagesEffects of Sexual Advertising On Customer Buying DecisionsIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument11 pagesLiterature ReviewOluwasanmi AkinbadeNo ratings yet

- Client Attachment To TherapistDocument11 pagesClient Attachment To Therapistjherrero22100% (2)

- Psychological Pricing Techniques As Perceived by FAITH Fidelis FacultyDocument56 pagesPsychological Pricing Techniques As Perceived by FAITH Fidelis FacultyMiko SabaulanNo ratings yet

- Torelli Et Al. (2011)Document2 pagesTorelli Et Al. (2011)Ryan ZhaoNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Emotional AdertisingDocument47 pagesThe Impact of Emotional Adertisingboris_sovNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Advertising SlogansDocument3 pagesThe Influence of Advertising SlogansSilia VoulgarakiNo ratings yet

- Niqsh'aDocument22 pagesNiqsh'aAmarendra SinghNo ratings yet

- A Content Analysis of Emotional and Rational Appeals in Selected Products AdvertisingDocument11 pagesA Content Analysis of Emotional and Rational Appeals in Selected Products AdvertisingPazirish Z. MirzaNo ratings yet

- Testing Cognitive Dissonance Theory Consumers Attitudes and Behaviors About NeuromarketingDocument7 pagesTesting Cognitive Dissonance Theory Consumers Attitudes and Behaviors About NeuromarketingA Miguel Simão LealNo ratings yet

- Title DefenseDocument5 pagesTitle DefenseJaqueline Mae AmaquinNo ratings yet

- A Meta-Analysis of The Effects of Humor On AdvertisingDocument22 pagesA Meta-Analysis of The Effects of Humor On Advertisingcartegratuita100% (1)

- Advances in Consumer Research Volume 10Document2 pagesAdvances in Consumer Research Volume 10nvkjayanthNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Emotional Branding On Consumer Behaviour:a Case Analysis of Kinder JoyDocument10 pagesThe Impact of Emotional Branding On Consumer Behaviour:a Case Analysis of Kinder JoyPrasanth KNo ratings yet

- Modeling Regret EffectsDocument23 pagesModeling Regret EffectssagalaidNo ratings yet

- The Paper Focuses On The Influence of NostalgiaDocument13 pagesThe Paper Focuses On The Influence of NostalgiaSadiaNo ratings yet

- Mehta 2000Document6 pagesMehta 2000CurvyBella BellaNo ratings yet

- A Dynamic Perspective On Affect and CreativityDocument8 pagesA Dynamic Perspective On Affect and CreativityJohn OMalleyNo ratings yet

- Attitudes Towards AdvertisingDocument14 pagesAttitudes Towards AdvertisingSajeeb ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Dream On Consumer Behavior - AdwaidDocument6 pagesImpact of Dream On Consumer Behavior - AdwaidAdwaid HariNo ratings yet

- Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology, Volume 36: The Origins and Organization of Adaptation and MaladaptationFrom EverandMinnesota Symposia on Child Psychology, Volume 36: The Origins and Organization of Adaptation and MaladaptationNo ratings yet

- A Study On Impact of Advertisement On Children Behaviour A Case Study of Sirsa Haryana PDFDocument32 pagesA Study On Impact of Advertisement On Children Behaviour A Case Study of Sirsa Haryana PDFTheri AjayNo ratings yet

- Concepts of Sexual Health Sex & You! (Modified for Jr. High)From EverandConcepts of Sexual Health Sex & You! (Modified for Jr. High)No ratings yet

- Chap Research MethodologyDocument4 pagesChap Research MethodologySenthil Kumar GanesanNo ratings yet

- Measurement Scavenger HuntDocument6 pagesMeasurement Scavenger HuntDakota HoneycuttNo ratings yet

- Controversial Advertising: Spirit Airlines: (Summary)Document1 pageControversial Advertising: Spirit Airlines: (Summary)AAMIRNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence in Relation To PsDocument8 pagesEmotional Intelligence in Relation To PsAndy MagerNo ratings yet

- Impact of Media Advertisement With Special Refference To Kottakkal MunicippalityDocument56 pagesImpact of Media Advertisement With Special Refference To Kottakkal Municippalitysk nNo ratings yet

- Consumer PerceptionDocument14 pagesConsumer PerceptionBablu JamdarNo ratings yet

- Sample ResearchDocument27 pagesSample ResearchFlora De MonteverdeNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Motivation On Purchase DecisionDocument12 pagesThe Effects of Motivation On Purchase DecisionQurat Khan0% (1)

- Mrs - Gunjan Sharma Rana Abhishek Pathak Mohit GoelDocument10 pagesMrs - Gunjan Sharma Rana Abhishek Pathak Mohit GoelmpimcaNo ratings yet

- Positive Thinking and Academic PerformanceDocument12 pagesPositive Thinking and Academic Performanceapi-267854035No ratings yet

- Comparing Methods For Measuring EmotionsDocument6 pagesComparing Methods For Measuring EmotionsnesumaNo ratings yet

- Play Therapy Treatment Planning and Interventions: The Ecosystemic Model and WorkbookFrom EverandPlay Therapy Treatment Planning and Interventions: The Ecosystemic Model and WorkbookRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- (Hollywood Poster) (Erik Kloeker)Document1 page(Hollywood Poster) (Erik Kloeker)Erik KloekerNo ratings yet

- Psihologia PozitivaDocument10 pagesPsihologia PozitivaClaudiaClotanNo ratings yet

- Caron - DSM at The Movies - Use of Media in Clinical or Educational SettingsDocument5 pagesCaron - DSM at The Movies - Use of Media in Clinical or Educational SettingsmentamentaNo ratings yet

- Comm Paper2Document7 pagesComm Paper2api-642868572No ratings yet

- The Links and Differences Between Advertising, Propaganda and Promotion, EssayDocument8 pagesThe Links and Differences Between Advertising, Propaganda and Promotion, EssayЯна СавоваNo ratings yet

- Role of Empathy in The Relationship Between Emotion-Inducing Advertisements and Purchasing DecisionsDocument20 pagesRole of Empathy in The Relationship Between Emotion-Inducing Advertisements and Purchasing DecisionssharmaikamaquiranNo ratings yet

- Sex Appeal PDFDocument5 pagesSex Appeal PDFabbey jamesNo ratings yet

- 99 Negotiating StrategiesDocument143 pages99 Negotiating StrategiesAnimesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Case 01 Buffett 2015 F1769Document36 pagesCase 01 Buffett 2015 F1769Josie KomiNo ratings yet

- (RIPE Series in Global Political Economy) Christopher May - The Global Political Economy of Intellectual Property Rights - The New Enclosures - Routledge (2000)Document213 pages(RIPE Series in Global Political Economy) Christopher May - The Global Political Economy of Intellectual Property Rights - The New Enclosures - Routledge (2000)José Miguel AhumadaNo ratings yet

- Saurav Kumar: EducationDocument2 pagesSaurav Kumar: Educationsaurav kumar singhNo ratings yet

- Pre-Course Work - Miralles, Ana FelnaDocument5 pagesPre-Course Work - Miralles, Ana FelnaAna Felna R. MirallesNo ratings yet

- Gerf Vi 2024 Pre-Announcement Ger EgyDocument2 pagesGerf Vi 2024 Pre-Announcement Ger Egyyimam seeidNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Who Is A Knowledge WorkerDocument24 pagesModule 3 Who Is A Knowledge WorkerLean Ashly MacarubboNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics - Activity 1Document3 pagesBusiness Ethics - Activity 1Charlou CalipayanNo ratings yet

- Brochure 2023Document3 pagesBrochure 2023Sandeep SNo ratings yet

- Income Tax Calculator For F.Y 2020 21 A.Y 2021 22 ArthikDishaDocument8 pagesIncome Tax Calculator For F.Y 2020 21 A.Y 2021 22 ArthikDishaGeetanjali BarejaNo ratings yet

- Best Practice For Solar Roof Top Projects in IndiaDocument172 pagesBest Practice For Solar Roof Top Projects in Indiaoptaneja48No ratings yet

- Summer Training BrochureDocument1 pageSummer Training BrochureAbhilashRayaguruNo ratings yet

- DTC18 Report LRDocument16 pagesDTC18 Report LRarunaNo ratings yet

- Ole of Management Information System in Banking Sector IndustryDocument3 pagesOle of Management Information System in Banking Sector IndustryArijit sahaNo ratings yet

- # Macroeconomics Chapter - 1Document31 pages# Macroeconomics Chapter - 1Getaneh ZewuduNo ratings yet

- Additive Manufacturing As An Enabling Technology For Digital Construction PDFDocument17 pagesAdditive Manufacturing As An Enabling Technology For Digital Construction PDFYudanto100% (1)

- Elec Midterm ReviewerDocument16 pagesElec Midterm ReviewerArgie DeguzmanNo ratings yet

- MCQ SDLCDocument7 pagesMCQ SDLCShipra Sharma100% (1)

- Add Users To Office 365 With Windows PowerShellDocument3 pagesAdd Users To Office 365 With Windows PowerShelladminakNo ratings yet

- Tax RTP 2 Nov 2020Document41 pagesTax RTP 2 Nov 2020KarthikNo ratings yet

- Transdisciplinary Journal in Science and Engineering (TJES) Call For ContributionsDocument1 pageTransdisciplinary Journal in Science and Engineering (TJES) Call For ContributionsBasarab NicolescuNo ratings yet

- 4) Overland Trade Routes in The Middle EastDocument3 pages4) Overland Trade Routes in The Middle EastSyed Ashar ShahidNo ratings yet

- Kashmir Festival - FinalsDocument27 pagesKashmir Festival - FinalsAhmed Mazhar KhanNo ratings yet

- 661 - Gandhi DarshanDocument5 pages661 - Gandhi DarshanrtiNo ratings yet

- Presentation of The Project Canvas ANR ModelDocument7 pagesPresentation of The Project Canvas ANR Modelantonionietorodriguez ConsultorNo ratings yet

- 社畜天狗さん おみそ - IllustrationsDocument1 page社畜天狗さん おみそ - IllustrationsAahanaNo ratings yet

- Corruption in International BusinessDocument20 pagesCorruption in International BusinessZawad ZawadNo ratings yet

- Nuevo Documento de Texto1111111111Document101 pagesNuevo Documento de Texto1111111111Netflix FamiliaNo ratings yet

- Raute PDFDocument3 pagesRaute PDFRamuni GintingNo ratings yet

- WAPCOS LimitedCentre For Environment and Construction ManagementDocument4 pagesWAPCOS LimitedCentre For Environment and Construction ManagementRafikul RahemanNo ratings yet