Professional Documents

Culture Documents

MR Tom The True Story of Tom Simpson

Uploaded by

Mousehold Press0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

306 views6 pagesAll cyclists, and everyone who wants to know about modern sport, should read it. Here’s a story of triumph, for this book is about Tom Simpson’s life, not his tragic death. We travel from the cinder tracks of the industrial north-east to European glory, from the British club scene to a world championship and the yellow jersey in the Tour de France. An intimate portrait of an exceptional man, this biography tells us about the private as well as the public Simpson, and there’s new information for even the most knowledgeable fan. Brilliant.

Original Title

Mr Tom the true story of Tom Simpson

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentAll cyclists, and everyone who wants to know about modern sport, should read it. Here’s a story of triumph, for this book is about Tom Simpson’s life, not his tragic death. We travel from the cinder tracks of the industrial north-east to European glory, from the British club scene to a world championship and the yellow jersey in the Tour de France. An intimate portrait of an exceptional man, this biography tells us about the private as well as the public Simpson, and there’s new information for even the most knowledgeable fan. Brilliant.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

306 views6 pagesMR Tom The True Story of Tom Simpson

Uploaded by

Mousehold PressAll cyclists, and everyone who wants to know about modern sport, should read it. Here’s a story of triumph, for this book is about Tom Simpson’s life, not his tragic death. We travel from the cinder tracks of the industrial north-east to European glory, from the British club scene to a world championship and the yellow jersey in the Tour de France. An intimate portrait of an exceptional man, this biography tells us about the private as well as the public Simpson, and there’s new information for even the most knowledgeable fan. Brilliant.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

You are on page 1of 6

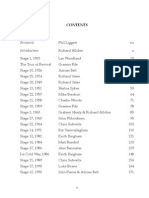

CONTENTS

Foreword by Phil Liggett

Author’s Introduction to Second Edition

Preface: Getting It Over With

1 A Boy and His Bike

2 Super Pursuiter

3 The Sparrow Flies Down Under

4 Distance Makes the Legs Grow Stronger

5 The Brittany Landings

6 Classics, Monuments, Marriage and the Tour

7 Darkest Before the Dawn

8 The Major Wears Yellow

9 The Lion Goes from Strength to Strength

10 Tommi Simpsoni

11 ‘I Hope That One Day, Mr Prime Minister’

12 After the Rainbow

13 ‘Put Me Back on My Bike’

Appendix: Tom Simpson’s Palmares by Richard Allchin

Reproduced by kind permission of Jeremy Mallard, from his

limited-edition print ‘Simpson on Ventoux’

Preface

GETTING IT OVER WITH

When Tom Simpson died on Mont Ventoux whilst competing in

the 1967 Tour de France traces of drugs from the amphetamine

group were found in his body. Similar drugs were allegedly found

in his clothing. There, I’ve said it, got it out of the way right at the

beginning of the book.

Because of this, notwithstanding that the official cause of his

death, arrived at after investigation by the French authorities, was

heart failure due to dehydration and heat exhaustion, to which it

was said that the drugs could have been a contributory factor, Tom

Simpson has been portrayed as anything from a straightforward

cheat, responsible single-handedly for subverting the ethics of

sport, to a hapless victim whose wings got burned flying too close

to his dream of winning the Tour de France.

Neither of these theories are true and both do him, and come to

that the people who propound them, a disservice. Tom was neither

of these. He was a talented, driven professional who paid the

ultimate price for pushing a bad situation too far. He was no cheat.

To my mind a cheat does something his competitors do not and

thereby gains an advantage. This is clearly not the case. Stimulants

such as amphetamines were widely used in cycling in the sixties

and today the sport is still beset by a drugs problem – the events of

the 1998 Tour de France highlight that. Indeed, a drug culture has

existed in professional cycling almost since the first race was run.

As for being a victim, forget it! Tom knew what he was doing. It

was not something he did lightly, too often or without professional

advice.

The truth is that Tom knew nothing of the dark side of professional

bike racing when he went to live in France in the spring of 1959,

but he quickly realised that sometimes he was beaten in races that

he just had to win by riders of lesser ability who had taken drugs.

What was he going to do? Forget about it all and take the next boat

home? Not Tom; he could never have done that, it wasn’t in his

nature. So, he turned to the people he’d met over there – people he

respected – and, like many before him, and since, he began to use

drugs – stimulants, because that’s what they used then. Not often,

but use them he did, and I can’t change that. It wasn’t something

he was particularly proud of, and I know that it worried him. He

would have liked not to have done it; indeed, as we shall see from

one particular incident later in the book, he was one of the few top

riders who supported what meagre efforts cycling authorities were

making at the time to rid the sport of this problem.

Unfortunately, the part that drugs played in Tom’s death has

been picked over to such an extent that it has overshadowed

everything he achieved in his remarkable career, a career that

more than 30 years after his death has yet to be equalled by any of

his countrymen. I hope that this book will go some way towards

restoring that balance. It won’t be a whitewash. I won’t try to present

him as a saint. I won’t be making excuses for him; he doesn’t need

them. I will just tell you the story of his amazing life, and I hope,

at the end of it all, that you will understand Tom Simpson and why

I felt that this book needed to be written for his sake. Why I could

no longer bear to see a man who had already lost his life, also lose

his reputation.

‘There is nothing to prevent him starting the stage, but everything to

prevent him finishing. He will be riding virtually one-handed.’ Under the

watchful gaze of Dr Dumas and a posse of photographers, Tom struggles

towards retirement during Stage 17 of the 1966 Tour de France.

Tour of Lombardy 1965: Tom, in the rainbow jersey, has ridden

everybody off his wheel to win alone on the Como track by

three minutes – ‘an exploit in the tradition of Fausto Coppi’.

You might also like

- In Search of Robert Millar: Unravelling the Mystery Surrounding Britain’s Most Successful Tour de France CyclistFrom EverandIn Search of Robert Millar: Unravelling the Mystery Surrounding Britain’s Most Successful Tour de France CyclistRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (22)

- Simon MurrayDocument2 pagesSimon MurrayJerson Ramos Huerta100% (2)

- Thompson, Geoff - The Throws & Take-Downs of Freestyle WrestlingDocument96 pagesThompson, Geoff - The Throws & Take-Downs of Freestyle WrestlingDave93% (15)

- Lights Out, Full Throttle: The Good the Bad and the Bernie of Formula OneFrom EverandLights Out, Full Throttle: The Good the Bad and the Bernie of Formula OneNo ratings yet

- Half Man, Half Bike: The Life of Eddy Merckx, Cycling's Greatest ChampionFrom EverandHalf Man, Half Bike: The Life of Eddy Merckx, Cycling's Greatest ChampionNo ratings yet

- Op BARRAS-SASDocument7 pagesOp BARRAS-SASzoobNo ratings yet

- D&D 3.5 - Dungeon Tiles Set 7 - Fane of The Forgotten GodsDocument16 pagesD&D 3.5 - Dungeon Tiles Set 7 - Fane of The Forgotten GodsKumo Wilendorf100% (2)

- Lance, The Lies and MeDocument9 pagesLance, The Lies and MecaptainsneddonNo ratings yet

- Lance ArmstrongDocument14 pagesLance ArmstrongVishakha UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Slaying the Badger: Greg LeMond, Bernard Hinault, and the Greatest Tour de FranceFrom EverandSlaying the Badger: Greg LeMond, Bernard Hinault, and the Greatest Tour de FranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (32)

- The Badger: The Life of Bernard Hinault and the Legacy of French CyclingFrom EverandThe Badger: The Life of Bernard Hinault and the Legacy of French CyclingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Lance Armstrong's War: One Man's Battle Against Fate, Fame, Love, Death, Scandal, and a Few Other Rivals on the Road to the Tour de FranceFrom EverandLance Armstrong's War: One Man's Battle Against Fate, Fame, Love, Death, Scandal, and a Few Other Rivals on the Road to the Tour de FranceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (71)

- Tom Rubython, Keith Sutton - The Life of Senna - The Biography of Ayrton Senna-BusinessF1 Books (2004)Document942 pagesTom Rubython, Keith Sutton - The Life of Senna - The Biography of Ayrton Senna-BusinessF1 Books (2004)sharma20keshavNo ratings yet

- 'Registrar's Errors.'Document17 pages'Registrar's Errors.'Mark Richard Hilbert (Rossetti)No ratings yet

- Le Tour: A History of the Tour de FranceFrom EverandLe Tour: A History of the Tour de FranceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- To the Last Ridge: The World War One Experiences of W H DowningFrom EverandTo the Last Ridge: The World War One Experiences of W H DowningRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (5)

- Stella Remington Open Secret - 2002Document192 pagesStella Remington Open Secret - 2002gladio67100% (1)

- Mapping Le Tour: The unofficial history of all 100 Tour de France racesFrom EverandMapping Le Tour: The unofficial history of all 100 Tour de France racesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Simon Murray: Three Lives in One: Activity 1Document5 pagesSimon Murray: Three Lives in One: Activity 1kuti68kutiNo ratings yet

- Truman Show analysis questions breakdownDocument4 pagesTruman Show analysis questions breakdownKobe StephensNo ratings yet

- David Walsh, July 2001Document6 pagesDavid Walsh, July 2001RaceRadioNo ratings yet

- Jimmy Baund and the Holy Figurine: A Fictional Spy SpoofFrom EverandJimmy Baund and the Holy Figurine: A Fictional Spy SpoofNo ratings yet

- Ventoux: Sacrifice and Suffering on the Giant of ProvenceFrom EverandVentoux: Sacrifice and Suffering on the Giant of ProvenceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- The Inside Track: Paddocks, Pit Stops and Tales of My Life in the Fast LaneFrom EverandThe Inside Track: Paddocks, Pit Stops and Tales of My Life in the Fast LaneRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- A Case for Murder: Brittany Murphy Files - Second EditionFrom EverandA Case for Murder: Brittany Murphy Files - Second EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Standing in Line: A Memoir: 30 Years of Obsessive Queuing at WimbledonFrom EverandStanding in Line: A Memoir: 30 Years of Obsessive Queuing at WimbledonNo ratings yet

- CARS AT SPEED: Classic Stories from Grand Prix’s Golden Age By Robert DaleyFrom EverandCARS AT SPEED: Classic Stories from Grand Prix’s Golden Age By Robert DaleyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- From The Pen of J. B. WadleyDocument9 pagesFrom The Pen of J. B. WadleyMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Parry Thomas: The First Driver to be Killed in Pursuit of the Land Speed RecordFrom EverandParry Thomas: The First Driver to be Killed in Pursuit of the Land Speed RecordNo ratings yet

- Racing Through the Dark: Crash. Burn. Coming Clean. Coming Back.From EverandRacing Through the Dark: Crash. Burn. Coming Clean. Coming Back.Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Boston Marathon: Year-by-Year Stories of the World's Premier Running EventFrom EverandBoston Marathon: Year-by-Year Stories of the World's Premier Running EventNo ratings yet

- Au Revoir, Tristesse: Lessons in Happiness from French LiteratureFrom EverandAu Revoir, Tristesse: Lessons in Happiness from French LiteratureRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Cycling+ - Boxed inDocument2 pagesCycling+ - Boxed inalexmurraysmithNo ratings yet

- Three Million WheelbarrowsDocument12 pagesThree Million WheelbarrowsMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- The Wounded Earth - What World Will Our Children Inherit?Document6 pagesThe Wounded Earth - What World Will Our Children Inherit?Mousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Wandering in Norfolk SnippetDocument17 pagesWandering in Norfolk SnippetMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- An Extract From A Corinthian EndeavourDocument10 pagesAn Extract From A Corinthian EndeavourMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Picture Sec 1Document8 pagesPicture Sec 1Mousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Norwich 1144 A Jew's Tale - ExtractDocument17 pagesNorwich 1144 A Jew's Tale - ExtractMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Lesson 9Document15 pagesLesson 9Mousehold PressNo ratings yet

- The Beauty of RustDocument9 pagesThe Beauty of RustMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Lesson 9Document15 pagesLesson 9Mousehold PressNo ratings yet

- HarbertDocument5 pagesHarbertMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- ContentsDocument1 pageContentsMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- An Extract From A Corinthian EndeavourDocument10 pagesAn Extract From A Corinthian EndeavourMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Ocaña - ExtractDocument6 pagesOcaña - ExtractMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- ContentsDocument1 pageContentsMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Stillness Lies DeepDocument4 pagesStillness Lies DeepMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Five Norwich LivesDocument4 pagesFive Norwich LivesMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Viva La Vuelta! - The Story of Spain's Great Bike Race 1935-2013Document8 pagesViva La Vuelta! - The Story of Spain's Great Bike Race 1935-2013Mousehold PressNo ratings yet

- AmigoDocument12 pagesAmigoMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Squit and Wit ... With Knobs On!Document7 pagesSquit and Wit ... With Knobs On!Mousehold PressNo ratings yet

- GOLDEN STAGES OF THE TOUR DE FRANCE - 2nd EditionDocument9 pagesGOLDEN STAGES OF THE TOUR DE FRANCE - 2nd EditionMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- COME YEW ON, TERGETHER!:A Rich Crop of Norfolk Dialect Writing Harvested by Keith SkipperDocument8 pagesCOME YEW ON, TERGETHER!:A Rich Crop of Norfolk Dialect Writing Harvested by Keith SkipperMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Dennis Horn - Racing For An English RoseDocument8 pagesDennis Horn - Racing For An English RoseMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Shay Elliott: The Life and Death of Ireland's First Yellow JerseyDocument12 pagesShay Elliott: The Life and Death of Ireland's First Yellow JerseyMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Chronicles From The EdgeDocument6 pagesChronicles From The EdgeMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- John Coulson: A Bit of An All-Rounder: 40 Years of Cycling PhotographyDocument12 pagesJohn Coulson: A Bit of An All-Rounder: 40 Years of Cycling PhotographyMousehold Press100% (1)

- A Racing Cyclist's Worst Nightmare and Other Stories of The Golden AgeDocument10 pagesA Racing Cyclist's Worst Nightmare and Other Stories of The Golden AgeMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Unsurpassed: The Story of Tommy Godwin, The World's Greatest Distance CyclistDocument15 pagesUnsurpassed: The Story of Tommy Godwin, The World's Greatest Distance CyclistMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Shay Elliott: The Life and Death of Ireland's First Yellow JerseyDocument12 pagesShay Elliott: The Life and Death of Ireland's First Yellow JerseyMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Brian Robinson: Pioneer ExtractDocument27 pagesBrian Robinson: Pioneer ExtractMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Lapize ExtractDocument11 pagesLapize ExtractMousehold PressNo ratings yet

- Robin Clay - Backgammon WinninDocument87 pagesRobin Clay - Backgammon WinninsuitelouNo ratings yet

- TOCA Race DriverDocument4 pagesTOCA Race Driversigne.soderstrom1785No ratings yet

- 4320 Tractor IntroductionDocument9 pages4320 Tractor Introductionodali batista0% (1)

- Aldo Dwarf RogueDocument1 pageAldo Dwarf RogueNon ejNo ratings yet

- 2019-01-01 British Chess MagazineDocument64 pages2019-01-01 British Chess MagazineLucas Leite100% (2)

- War Diary - Sept 1942Document180 pagesWar Diary - Sept 1942Seaforth WebmasterNo ratings yet

- Perpectives: Bsce 5C-Steel Design Architectural Plan Proposed Three - Storey Commercial BuildingDocument15 pagesPerpectives: Bsce 5C-Steel Design Architectural Plan Proposed Three - Storey Commercial BuildingShōya IshidaNo ratings yet

- Space Shooter GameDocument18 pagesSpace Shooter GameSowmya Srinivasan100% (2)

- Winnie L'ourson Et L'anniversaire RoyaleDocument15 pagesWinnie L'ourson Et L'anniversaire RoyaleActuaLittéNo ratings yet

- BM1606A5GENFIG1Document448 pagesBM1606A5GENFIG1locario1100% (2)

- SotDL - Spell Cards - SotDL PathDocument18 pagesSotDL - Spell Cards - SotDL PathIzael Evangelista100% (1)

- Gundam Sentinel Mobile Suit DetailsDocument2 pagesGundam Sentinel Mobile Suit DetailsMark AbNo ratings yet

- Reglas para Añadir Al Verbo Principal: Am Is Are ReadDocument8 pagesReglas para Añadir Al Verbo Principal: Am Is Are ReadSamuel Junior Miranda PinzonNo ratings yet

- 7833 Fit - CS Final ExamDocument22 pages7833 Fit - CS Final ExamMariette Alex AgbanlogNo ratings yet

- Eagle Aluminium Brochure (Optimised) PDFDocument9 pagesEagle Aluminium Brochure (Optimised) PDFTonderai RusereNo ratings yet

- MessagesDocument5 pagesMessagesrtg_moviemakerNo ratings yet

- Equipment - d6 Pool 'Simple' - 2021Document3 pagesEquipment - d6 Pool 'Simple' - 2021Axel RagnarsonNo ratings yet

- 2 Series Brochure - 0 PDFDocument4 pages2 Series Brochure - 0 PDFRod JesusislordNo ratings yet

- Article Errors - Answer Key: Exercise 1: Choosing Articles in A ParagraphDocument2 pagesArticle Errors - Answer Key: Exercise 1: Choosing Articles in A Paragraphzander_knightt100% (2)

- Warfleets FTL - Basic Rulebook v1.8Document15 pagesWarfleets FTL - Basic Rulebook v1.8LucheNo ratings yet

- Kickboxing ManualDocument5 pagesKickboxing ManualBoky DjordjevicNo ratings yet

- Go Winds: NEW Manyfaces of Go NEW Yutopian Books Handbook of Star Point JosekiDocument12 pagesGo Winds: NEW Manyfaces of Go NEW Yutopian Books Handbook of Star Point JosekiAnonymous tadjbbYIzeNo ratings yet

- E2876Document3 pagesE2876criveraNo ratings yet

- Katalog Otokam ScaniaDocument284 pagesKatalog Otokam ScaniaIwan Setiadi100% (2)

- Sport and Energy Drinks Consumption Before, During and After TrainingDocument7 pagesSport and Energy Drinks Consumption Before, During and After TrainingGhana FirstaNo ratings yet

- Variable Camshaft Timing - Variable Valve TimingDocument85 pagesVariable Camshaft Timing - Variable Valve TiminglibertyplusNo ratings yet

- Rule Book: The Supremacy of Cavalry in The Crusader Era 11th-12th CenturyDocument16 pagesRule Book: The Supremacy of Cavalry in The Crusader Era 11th-12th CenturyDWSNo ratings yet

- Narrative Report On The Training of Basketball Coaches and OfficiatingDocument2 pagesNarrative Report On The Training of Basketball Coaches and Officiating100608No ratings yet