Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Preparing For The...

Uploaded by

David Josué Carrasquillo MedranoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Preparing For The...

Uploaded by

David Josué Carrasquillo MedranoCopyright:

Available Formats

Clark University

Review: [untitled] Author(s): Antonio Luna Source: Economic Geography, Vol. 74, No. 2 (Apr., 1998), pp. 194-196 Published by: Clark University Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/144285 . Accessed: 27/09/2011 20:43

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Clark University is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Economic Geography.

http://www.jstor.org

194

ECONOMIC GEOGRAPHY

aspects of hooks's theorizing. He credits Gillian Rose, but he might more fully register the criticalwork of Caren Kaplanand Neil Smith and Cindi Katz. But, more importantly, hooks's theorizing itself emerges out of a community of writing and her position has been debated within that community, sometimes in ways that problematize the claims that Soja makes for it. Sara Suleri, for example, criticizes hooks precisely for exacerbating divisions between African American and "Third World" feminists. Whether or not one appreciates and endorses Suleri's polemical style of argumentation,there is a community of debate that Soja chooses to ignore. When it comes to his treatment of feminist geography, Soja is engagingly open about the fact that his graduate student, BarbaraHooper, has "triedwith some success to control my impulses to tweak a few of the feminist geographerswho seemed to dismiss my admittedly gender-biased Postmodern Geographies as masculinist posing tout court" (p. 13) (Thank you, Barbara) and is positive about Gillian Rose's attempts to imagine thirdspace. But on the whole, feminist geography comes off ratherbadly:"Despite the development of a vigorous feminist movement and the centrality of space in the discipline, there have been relatively few contributions by geographers to what I have described as the postmortem spatial feminist critique" (p. 119). He notes that this has changed in the past few years, citing Gillian Rose, but claims that "an appreciation for the wider range of othernesses and marginalities"is "stillmissing"(p. 125). It is difficult to evaluate this claim; with no references to key publications such as Gender Place and Culture, Mapping Desire, Writing Women and Space: Colonial and Postcolonial Geographies-journals and large edited volumes that introduce the uninitiated to the vast and lively subfields of postcolonial feminist and queer geographies-it is unclear whether Soja is unfamiliarwith or dismissive of a good deal of contemporary work within geography.At one level, this is

surely a petty complaint, but, at another (and I anticipate that Soja will sympathize with this point) it speaks directly to gender/sexualpolitics in the discipline of geography and to the question of who has the right and privilege to narrate whose history. Despite (or perhaps because) of the fact that I found myself in vigorous debate with Thirdspaceat certain points, it is an important and invigorating text. The last three chapters are, quite simply, essential reading in any upper-level urban geography class. They offer compelling examples of new ways of writing and a window into the concept of thirdspace which disrupts and energizes conventional accounts of the urban. And if I am uneasy with Soja's encounter with feminism, I am nonetheless deeply appreciative of the political vision and commitment that underlies it. Geraldine Pratt University of British Columbia Preparing for the Urban Future: Global Pressures and Local Forces. Edited by Michael A. Cohen, Blair A. Ruble, Joseph S. Tulchin, and Allison M. Garland. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 1996. In June 1994 the Woodrow Wilson Center's comparative urban program, in cooperation with the Urban Development Division of the World Bank, organized an open discussion about the current state and evolution of the world's cities as preparation for Habitat II (Istanbul, June 1996). This book is the product of that discussion among academics, practitioners, and local and national officials. The main goal of the book is to explore how cities' issues have changed since Habitat I in 1976. The two most important changes are the disappearanceof the EastWest political and economic dichotomy after the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989 and the increasing rate of urbanizationworldwide. One of the strongest points of this book is a diverse thematic and disciplinary focus. Seventeen chapters, classified in six

BOOKREVIEWS

195

different sections, attempt to cover a broad range of topics on internationalization, globalization, and growth of transnational agreements. The four chapters in Part 1 explore "Urban Convergence and a New Paradigm." Michael Cohen looks at how the increasing internationalization of human activities in the last 20 years has created links among cities worldwide, so that certain problems are now shared by cities of developed and developing countries. Hank Savitch goes a step further and proposes a set of policy strategies for cities to increase the rate of adaptability to a changing global environment. Although government-induced development is limited, local officials should play with their cities' natural advantages, support social capital, and increase their relationshipwith other cities. Martha Schteingart analyzes the changes that have occurred in the urban arena between Habitat I and II. She is critical of the neoliberal rhetoric of the present situation,which stresses the liberation of markets and the deregulation and privatizationof most urban services. Under the generic title "From Global to Local," the articles in Part 2 explore the tensions produced by global forces in urban settings. Global and local are seen not as contradictoryphenomena but as different responses to identical processes. Global changes strongly affect urban realities. It is also the case, however, that local communities and institutions may influence the lives of people on the other side of the globe. Mohamed Halfani uses his native Africa to analyze this process in some sub-Saharan cities. African cities have encountered tremendous crisis due to the confluence of important "global" trends. Halfani points to the impact of South African investments, the revitalization of urban governance, the importance of traditional kinship institutions, and the vitality of the informal sector as mediators of the impact of globalization. In an excellent article, Nezar AlSayyad explores the importance of urbanism as a way of maintaining the specificity of local cultures. He

analyzes three different historical phases (colonial, independence nation-state building, globalization) and their corresponding urban forms (hybrid, modern-pseudomodern, postmodern). Urbanism becomes one of the representations of how the forms of global domination are mediated by local struggles. In a final article in this section, Weiping Wu explores alternativestrategies and practices among the cities of New York,Barcelona, Santiago,and Shanghaias they seek a place in the new global economic order. He points out two different paths to urban economic competition: a low road of increasing competitiveness by decreasing labor cost under a deregulated labor market and a high road focusing on efficiency enhancement and innovation. Part 3 explores the social and economic dilemmas of cities at the end of the century. The various authors argue that national and regional actors are less important in the globalization era, while local actors are more visible, endorsing the specific needs of each locality. In a short article, Michael J. White analyzes the positive effects that urbanizationhas had in accelerating the demographic transition. Next, Julie Roque exposes the negative effects of the technological change. She proposes the creation of institutions to ameliorate the disparitiescreated by uneven technological development and the informational apartheid. She falls short, however, in explaining how those institutions can be implemented. In another chapter Edmundo Werna, Illona Blue, and Trudy Harpham analyzethe changing agenda for urban health. They propose a more integrated approach that focuses on institutional integration and an increasing role for local organizations(community participation). The fourth part evaluates the dilemmas of urban governance. K.C. Sivaramakrishnan,drawinginformation mostly from cities in India and China, describes the anarchicalquality of urban governance. He favors a certain degree of decentralization and an increase in the proximity between citizen and government, but always in an environment of political and institutional

196

ECONOMIC GEOGRAPHY

transparency and accountability. Jordi Borjaanalyzesthe case of Barcelonaand its success in attracting capital to build its tourism industry. He stresses the importance of leadership in the new roles and forms of urban governing. It is not clear, however, how this particular case can be extrapolatedto other regions with different institutional structures. Finally, Maria Elena Ducci explores the politics of urban sustainability.The contrastingneeds of the green agenda (global problems) and the brown agenda (local problems) are analyzed. The new urban agenda in developing countries is no longer the struggle for land but the struggle for a better quality of life and a better urban environment. The fifth part of the book deals with changes in the urban landscape. Galia and Guy Burgel analyze the failures of past strategies of urban development. They propose experimenting with new methodologies based on small-scale pragmatic projects and citizen participation. Robert Bruegmann argues that the new urbanism is alreadytaking place in the democratized environment of the United States, where the city is shaped by every citizen, every organization,every day. In the final part, Lisa R. Peattie proposes a new research agenda for urban studies based on a return to case studies. Urban processes are to be understood through case analysis and comparision. Finally, Richard Stern analyzes the disciplinary dilemma of urban studies and summarizes the most significant literature about urban issues since the 1960s, focusing mostly on urban sociologists and urban geographers. Overall, this collection is a valuable contributionto recent debates on urbanissues, from a globalization perspective. Those interested in a broad overview of recent issues in urbanpractice and theory will find Preparingfor the Urban Future enlightening and useful. For those who want a deeper analysisof the future of the world's cities, however, this book only offers an introduction to urban debates.

Antonio Luna Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona Europe's Population in the 1990s. Edited by David Coleman. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. Europe'sPopulationin the 1990s is a collection of papers on recent demographic trends in European countries, focusing on divergence and convergence at the national and, to a lesser extent, subnationallevels. Most of the chapters were originallypresented at a conference held at the London Schoolof Economicsin April1993 and sponsored by the British Society for Population Studies. Consequently it is not surprising that, despite the Europeanfocus, most of the contributorsare from Britain,often emphasizing the British demographic experience more than those of other countries. The editor, David Coleman, contributed the prefaceand the firstchapter.The preface providesa brief overviewof the chapters as well as a brief descriptionof recent demothese graphictrends. Coleman characterizes trends, referred to as the second demographic transition,as being motivated by a over tradiof "primacy individualaspirations tional restraintsand obligationsto a wider society" (p. x). The first chapter describes recent fertilitypatternsin Europe,emphasizing the divergence across nations, such as decliningfertilityin southernEurope versus increasing fertilityin northernEurope.While both the preface and the first chapter are informative,providing a wealth of detailed data, I was surprised by Coleman's use of value-ladenlanguage. Examplesinclude the births," repeateduse of the term "illegitimate reference to the United States as "NeoEast European Europe,"and characterizing countriesas being "on the wrong side of the Iron Curtainafter 1945"(p. vi). In the second chapter, Kathleen E. Kiernan describes changes in marriage, divorce, cohabitation,and single-parenthood patternsacross Europeannations, as well as gender differences in labor force participation, earnings, and attitudes toward gender roles and household responsibilities. She

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Communication DisordersDocument23 pagesCommunication DisordersLizel DeocarezaNo ratings yet

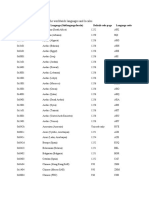

- The Following Table Shows The Worldwide Languages and LocalesDocument12 pagesThe Following Table Shows The Worldwide Languages and LocalesOscar Mauricio Vargas UribeNo ratings yet

- Postcolonialism Nationalism in Korea PDFDocument235 pagesPostcolonialism Nationalism in Korea PDFlksaaaaaaaaNo ratings yet

- Short Exploration of Madame Duval's Character in Frances Burney's Evelina (Jan. 2005? Scanned)Document2 pagesShort Exploration of Madame Duval's Character in Frances Burney's Evelina (Jan. 2005? Scanned)Patrick McEvoy-Halston100% (1)

- Every Muslim Is NOT A Terrorist - Digital PDFDocument145 pagesEvery Muslim Is NOT A Terrorist - Digital PDFSuresh Ridets100% (1)

- Consumer Production in Social Media Networks: A Case Study of The "Instagram" Iphone AppDocument86 pagesConsumer Production in Social Media Networks: A Case Study of The "Instagram" Iphone AppZack McCune100% (1)

- Study-Guide-Css - Work in Team EnvironmentDocument4 pagesStudy-Guide-Css - Work in Team EnvironmentJohn Roy DizonNo ratings yet

- Guro21c2 Rvi b01Document44 pagesGuro21c2 Rvi b01Pau Torrefiel100% (1)

- Social Skills Training For Children With Autism - Pediatric ClinicsDocument7 pagesSocial Skills Training For Children With Autism - Pediatric ClinicsMOGANESWARY A/P RENGANATHANNo ratings yet

- INTRODUCTIONDocument3 pagesINTRODUCTIONmascardo franzNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plans Ap WH Sept 8-11Document2 pagesLesson Plans Ap WH Sept 8-11api-259253396No ratings yet

- 3.20 Quizlet Vocabulary Practice - Promotion - CourseraDocument1 page3.20 Quizlet Vocabulary Practice - Promotion - CourseraSneha BasuNo ratings yet

- Quran Translated Into BrahuiDocument816 pagesQuran Translated Into Brahuiwhatsupdocy100% (1)

- Gender Across Languages - The Linguistic Representation of Women and Men Marlis Hellinger, Hadumod Bussmann PDFDocument363 pagesGender Across Languages - The Linguistic Representation of Women and Men Marlis Hellinger, Hadumod Bussmann PDFDopelganger MonNo ratings yet

- PHAR - GE-WOR 101-The Contemporary World For BSP PDFDocument12 pagesPHAR - GE-WOR 101-The Contemporary World For BSP PDFIra MoranteNo ratings yet

- 4idealism Realism and Pragmatigsm in EducationDocument41 pages4idealism Realism and Pragmatigsm in EducationGaiLe Ann100% (1)

- The Rise of StalinDocument14 pagesThe Rise of StalinArthur WibisonoNo ratings yet

- 1st - Hobbs and McGee - Standards PaperDocument44 pages1st - Hobbs and McGee - Standards Paperapi-3741902No ratings yet

- Constructing A Replacement For The Soul - BourbonDocument258 pagesConstructing A Replacement For The Soul - BourbonInteresting ResearchNo ratings yet

- Grade 11 Arts and Design Prospectus Version 2Document1 pageGrade 11 Arts and Design Prospectus Version 2kaiaceegees0% (1)

- 16 - F.Y.B.Com. Geography PDFDocument5 pages16 - F.Y.B.Com. Geography PDFEmtihas ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Indus River Valley CivilizationDocument76 pagesIndus River Valley CivilizationshilpiNo ratings yet

- Communication Process Worksheet 1Document3 pagesCommunication Process Worksheet 1Vernon WhiteNo ratings yet

- Von Clausewitz On War - Six Lessons For The Modern Strategist PDFDocument4 pagesVon Clausewitz On War - Six Lessons For The Modern Strategist PDFananth080864No ratings yet

- McGill Daily 98 - 29 - 26JAN08Document28 pagesMcGill Daily 98 - 29 - 26JAN08Will VanderbiltNo ratings yet

- The Malta & Gozo History & Culture Brochure 2010Document16 pagesThe Malta & Gozo History & Culture Brochure 2010VisitMalta67% (3)

- Teacher'S Guide: Exploratory Course On Agricultural Crop ProductionDocument20 pagesTeacher'S Guide: Exploratory Course On Agricultural Crop ProductionSharmain EstrellasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 3 Combined and Final Group2 1Document22 pagesChapter 1 3 Combined and Final Group2 1Kathryna ZamosaNo ratings yet

- Flexible Instruction Delivery Plan (FIDP) : Quarter: Performance StandardDocument9 pagesFlexible Instruction Delivery Plan (FIDP) : Quarter: Performance StandardWeng Baymac II75% (8)

- Applied English Phonology 3rd EditionDocument1 pageApplied English Phonology 3rd Editionapi-2413357310% (7)