Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Proceedings

Proceedings

Uploaded by

ChristyChanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Proceedings

Proceedings

Uploaded by

ChristyChanCopyright:

Available Formats

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications 2

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS The New Knowledge Globalization Era: Future Trends Changin. Corporate and Marketing Communications. ISBN: 978-960-9443-07-4 3

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications Athens University of Economics and Business, MBA Programme, Department of Busine ss Administration-Department of Marketing Communication George Panigyrakis, Prokopis Theodoridis and Anastasios Panopoulos (Eds.) The New Knowledge Globalization Era: Future Trends Changing Corporate Marketing Communications 16th International Conference on Corporate Marketing Communications (CMC 2011) Athens, 2011 Conference Proceedings ISBN: 978-960-9443-07-4 4

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications SPONSORS

COMMUNICATION SPONSOR

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications 6

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications CONTENTS

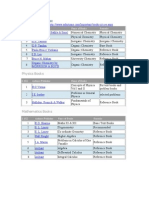

Editorial Note 11 Conference Chair 13 Organizing Committee 13 Scientific Committee 13 Keynote Speakers 13 Track Chairs 14 Reviewers 14 Interactive Marketing and Corporate Communications 17 Philip J. Kitchen; B. Zafer Erdogan; Tolga Torun: The Impact of IMC in Virtual 1 8 Communities on Brand Strategy for Universities Eirini Tsichla; Leonidas Hatzithomas; Christina Boutsouki: Gender differences in the 20 interpretation of a Museum s web atmosphere: A Selectivity Hypothesis Approach Yioula Melanthiou; Angelika Kokkinaki; Alexis Droussiotis: An Examination Of The 36 Use of Web 2.0 Services in Cyprus Prodromos Yannas; Alexandros Kleftodimos; Georgios Lappas:Online Political 38 Marketing in 2010 Greek Local Elections: The Shift from Web to Web 2.0 Campaigns Anastasios Panopoulos; Prokopis Theodoridis: A Proposed Framework For The 51 Adoption Of The Internet By Public Relations Managers Jenny Palla; Athina Y. Zotou; Anastasia Konstantopoulou: The moderating role of 65 product involvement on online attitude formation towards brands and websites Anastasios P. Pagiaslis; George Maglaras; Prokopis Theodoridis: The impact of 80 Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use on Online Purchases: a comparison of Buyers and Non-Buyers Perceptions Elli Vlachopoulou; Christina Boutsouki: Marketing on the go 95 Brand Communications 101 Georgia Stavraki; Emmanuella Plakoyiannaki: Appropriating an Artistic Brand 102 Meaning: a Case Study of Consumers Responses to Miro s Exhibition Irene Kamenidou; Spyridon Mamalis; Christina Intze: Consumers motivation and 113 choice criteria towards a brand: The case of Ardas Festival in Ardas area Evros, Greece

Ilias Kapareliotis; Gary Mulholland: Constructing the luxury concept: the brand 125 validation guide for luxury brands Athanasios Krystallis; Polymeros Chrysochou: Private vs. manufacturer brand 130 buyers: Do they show different preferences in product attributes? George J. Avlonitis; Lamprini Piha: Internal Brand Orientation: a prerequisite f or 132 brand excellence Erifili Papista; Sergios Dimitriadis:Exploring the Antecedents of Consumer-Brand 141 Identification Gary Mulholland; T. Williams:Emotional Intelligence and the leadership brand 143 7

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications Anna Zarkada: The personal branding phenomenon: Pushing epistemological boundaries or desperately marketing marketing? George Panigyrakis; Thanasis Poulis: Is there a standardized role for the brand manager internationally? A comparative study George Panigyrakis; Eirini Koronaki: Luxury brand consumption and cultural influences 146 157 170 Advertising and Media Insights 181 Leonidas Hatzithomas; Evaggelia Outra; Yorgos Zotos; Christina Boutsouki: Is 182 Humor a Countercyclical Advertising Strategy? Prokopis Theodoridis; Athina Y. Zotou; Antigone G. Kyrousi: Male & Female 194 Attitudes Towards Female Stereotypes: Some preliminary evidence Hsuan-Yi Chou; Cheng-Shih Lin: Consumers Responses to Spokespersons in 208 Homosexual Advertisements Emmanuel Heretakis: Towards the end of euphoria-Latest developments in the 210 Greek (old and new) media scene, from 2000 to 2010. Michael A. Belch; George E. Belch: Measuring Effectiveness In The New Media 212 Environment Hsuan-Yi Chou; Nai-Hwa Lien; Cheng-Shih Lin: The Effects of Song Choice in 219 Advertisements Eugenia Tzoumaka; Rodoula Tsiotsou; George Siomkos: Investigating the Role of 22 1 Sport Celebrity Characteristics on Endorsement Outcomes Don E. Schultz; Martin P. Block: Does Culture Drive Social Media Strategy? 223 Polymeros Chrysochou; Georgios Nikolakis; Athanasios Krystallis: Too fat to be a 237 model? The role of body image in advertising effectiveness of healthy food products Georgios Halkias; Flora Kokkinaki: Increasing Advertising Effectiveness through 239 Incongruity Based Tactics: The Moderating Role of Consumer Involvement George Gantzias: Cultural, Political and Social Destruction: Global Info Cash (G IC) 254 and Participatory Freedom (PF) Corporate Communications 255 Marwa Tourky; Philip Kitchen; Dianne Dean; Ahmed Shaalan: Institutionalizing CSR : 256 The role of Corporate Identity Management Ioanna Papasolomou; Haris Kountouros: Developing a framework for a successful 27 6 symbiosis of corporate social responsibility, internal marketing and employee

involvement procedures deriving Despina A. Karayanni; Christina 7 Medicines: Firms Communication Stelios C. Zyglidopoulos; Craig

from labour law C. Georgi; Constantinos A. Polydoros: Generic 28 Strategies And Phycisians Attitudes Carroll; Philemon Bantimaroudis: Framing the 300

Corporate World: The Impact of Corporate Social Performance on Media Attention and Prominence of Business Firms Sabine A. Einwiller; Christopher Ruppel: Trust in financial investments-Who or 3 12 what really counts Ioanna Papasolomou; Marlen Demetriou: Building corporate reputation through 314 the use of Corporate Social Responsibility and Cause Related Marketing: A longitudinal study of consumers perceptions in Cyprus Maria Pyrgeli; George Panigyrakis; E. Bakas: Patients' Satisfaction with Hospita l 325 Rehabilitation Services Ioannis Bombakos: Marketing and Human Resources Management for improving 329 hospital image. The case of the Greek state hospitals. 8

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications Panagiotis Gkorezis; Naoum Mylonas; Athina Besleme: The intervening role of 342 Organizational Identification on the relationship between Perceived External Prestige and Psychological Empowerment: The case of Greek Citizens Service Centers Retail Communications 351 Neesha McCrory; Ann Mitsis: Shopping Centre Environmental Factors: Does 352 Generation Y s Gender Influence Strategic Marketing Communication? An Australian Exploration Evangelia Chatzopoulou; Rodoula Tsiotsou; Kleanthis Sirakoulis: Examining the 36 2 effect of gender on motivational factors for visiting shopping malls Eleni K. Kevork; Adam P. Vrechopoulos: The Dynamics Of Servicescape As A 364 Customer Relationship Management Dimension In Web Retailing: An Inderdisciplinary Approach Maria Michailidis; Maria Economou: Corporate Social Responsibility Practices in 372 the Retail Industry in Cyprus George Baltas; Grigorios Painesis: Coupon Face Value Framing & The Moderating 38 4 Role of Stock-up Product Nature Irena Descubes: New Social Movements and Consumer Resistance to Hypermarket 398 Retail in the Czech Republic: Case NESEhnu Ioannis Krasonikolakis; Adam P. Vrechopoulos; Athanasia Pouloudi: 3D Retail Stor e 404 Typology George Panigyrakis; Antonios Zairis; George Stamatis: Consumer Behavior towards 406 Convenience Stores in Greece Marketing Communications 409 Georgios Avlonitis; Erifili Papista: An Examination of the Effect of Eco-Labelli ng on 410 Consumer Behaviour Despina A. Karayanni; Christina C. Georgi: Relating OTC consumer buying styles 4 12 with Over-the-Counter medicines marketing communications: Does one size fit all? Tareq Hashem: Using Demarketing strategies in tobacco companies to reduce 424 smoking in Jordan Katerina Sarri; Elpida Samara; Ioannis Bakouros; Paraskevi Giourka: Innovativene ss 432 in SMEs: Exploring the role of Marketing Innovation Lucia Porcu; Salvador del Barrio Garca; Philip J. Kitchen: Communication in a Tim e 446

of Financial Stringency: Revisiting Integrated Marketing Communication (IMC) Evangelia N. Markaki; Robert P. Ormrod; Theodoros Chatzipantelis: Integrating 44 8 Human Resource Management into Strategic Political Marketing Ivan Buksa; Ann Mitsis: Effectiveness of Athlete Endorsement Strategies and 450 Generation Y: An Australian Exploration Ahmed S. Shaalan; Jon Reast; Debra Johnson; Marwa E. Tourky: Unifying Guanxi462 Type Relationships and Relationship Marketing: A Conceptual Framework Branding and Corporate Communications 477 Wim J.L. Elving: The war for talent? The relevance of employer branding in job 4 78 advertisements for becoming an employer of choice Cleopatra Veloutsou; Luiz Moutinho: Tribal Behaviour and its Effect on Brand 492 Relationships: The View of the More Mature Market Bahar Yasin; Zehra Bozbay: The Impact Of Corporate Reputation On Customer 505 Trust 9

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications 10

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications The New Knowledge Globalization Era: Future Trends Changin. Corporate and Marketing Communications. Editorial Note

As the global economy seems to awaken from the darkness of an intense crisis, th e business landscape emerges in a newfound form. In the aftermath of the most intense shock the world economy has recently experienced, most Western economies exhibit signs of reviva l, yet everything has changed. In the dawn of this new era, the corporations and organizations that have surviv ed face new challenges, the society still suffers from the inevitable questioning of its fun damental values, the consumers have become skeptical, the citizens lack trust of institutions and gov ernments. Responding to the turbulent environment, both academics and practitioners seek t o put forward new strategies, models and techniques for corporate and marketing communications . The focal point of the 2011 conference lies in these future trends in corporate and marketing communications. Have certain communications practices been proved inadequate? Wh ich are the critical changes to be implemented? What is the role of corporate and market ing communications in the recuperation of the economy and the society? How can commu nications help rebuild trust in institutions and corporations? 16th This volume includes the papers of the International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications, an annual conference which is the meeting place for ac ademic researchers and teachers, as well as practitioners wishing to advance and create knowledge in the field of communications. The conference is by the MBA program of the departments of Business Administrati on and Marketing and Communication of Athens University of Economics and Business in Ap ril 2011 and is held in the Zappeion Hall, a place of historical importance. At the conference, theory and practice are combined to create a body of knowledg e available for solving current corporate issues and to provide solutions to the challenges prev ailing in today s business world. Thus, communications can serve as a valuable resource of the cor

porations realizing their potentials. This volume consists of both theoretical and empirical papers and extended abstr acts, including competitive and working papers in the fields of: interactive marketing and corpo rate communications, brand communications, advertising and media insights, corporate communications, retail communications, marketing communications as well as brand ing and corporate communications. Researchers from different cultural backgrounds have kept a broad perspective, i ndicating the increasing role of corporate and marketing communications. All papers went through the process of peer blind review, and were subsequently evaluated by the Review Committee. To be specific, the identity and affiliations of authors w ere kept separate from the actual work under review. The majority of the reviewers did not know th e author of the refereed papers, and the programme committees selections were made without knowi ng the authors' details. In the name of the CMC 2011 organizing committee, I would like to thank the revi ewers for their time and effort. Their kind participation in the review process for th e submitted papers has been essential for the successful implementation of the Conference. The significant contribution of those who submitted their papers to the impact o f the conference could not be left unmentioned. I would also like to acknowledge the importance o f the 11

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications volunteers contribution. Many thanks are given to the editorial team which tackle d proofreading and copy-editing for these proceedings. We wish you all the best with your research and development and hope that the wo rk in these proceedings helps you toward your goals. Prof. George G. Panigyrakis, Conference Chair 12

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications CONFERENCE CHAIR

Prof. George G. Panigyrakis, Director of the MBA programme, Athens University of Economics and Business, e-mail: pgg@aueb.gr ORGANIZING COMMITTEE

Avra Katzilieri, Athens University of Economics and Business Eirini Koronaki, Athens University of Economics and Business Antigone .yrousi, Athens University of Economics and Business Dr. Anastasios Panopoulos, University of Western Macedonia Dr. Athanasios Poulis, Athens University of Economics and Business Maria Pyrgeli, Athens University of Economics and Business Dr. Prokopis Theodoridis, University of Western Greece Dr. Rodoula Tsiotsou, University of Macedonia Dr. Anna Zarkada, Athens University of Economics and Business Athina Zotou, Athens University of Economics and Business Dr. Cleopatra Veloutsou, University of Glasgow Dr. Ilias Kapareliotis, Abertay Dundee University SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE

Prof. George Baltas, Athens University of Economics and Business Prof. Michael A. Belch, San Diego State University Prof. Philip J. Kitchen, Brock University Prof. Luiz Moutinho, University of Glasgow Dr. Anastasios P. Panopoulos, University of Western Macedonia Prof. George J. Siomkos, Athens University of Economics and Business Dr. Prokopis K. Theodoridis, University of Western Greece KEYNOTE SPEAKERS

Prof. Charles R. Taylor, Villanova University Prof. George J. Avlonitis, Athens University of Economics and Business 13

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications TRACK CHAIRS

Dr. Aikaterini Sarri, University of Western Macedonia Dr. Cleopatra Veloutsou, University of Glasgow Dr. Prokopis Theodoridis, University of Western Greece Prof. Don Schultz, Northwestern University Prof. George Baltas, Athens University of Economics and Business Prof. Michael Belch , San Diego State University Prof. Philip Kitchen , Brock University Prof. Prodromos Yannas , Technological Educational Institute of Western Macedoni a Prof. Wim Elving, University of Amsterdam Prof. Yorgos Zotos , Cyprus University of Technology Prof. George J. Siomkos, Athens University of Economics and Business Dr. Athanasios Krystallis , Aarhus School of Business Dr. Ioanna Papasolomou, University of Nicosia, Cyprus Dr. Rodoula Tsiotsou, University of Macedonia Dr. Anna Zarkada, Athens University of Economics and Business Prof. Sabine A. Einwiller, Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz REVIEWERS

Prof. George Baltas Department of Marketing and Communication, Athens University of Economics and Business, Greece george@aueb.gr Prof. Michael Belch San Diego State University, USA mbelch@mail.sdsu.edu Dr. Xuemei Bian University of Nottingham, Business School, UK Xuemei.Bian@nottingham.ac.uk Dr. George Christodoulides University of Birmingham, UK g.christodoulides@bham.ac.uk Dr. Fiona Davies Cardiff Business School, UK DaviesFM@cardiff.ac.uk

Prof. Bayram Zafer Erdogan Bilecik Universitesi,Ikt.Id.Bil. Fakultesi,Bilecik, Turkey bzerdogan@anadolu.edu.tr Dr. Leonidas Hatzithomas Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece leonidasnoe@yahoo.com Dr. Ilias Kapareliotis Abertay Dundee University, UK ikaparel@yahoo.gr 14

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications Dr. Despina Karayanni University of Patras, Greece karayan@otenet.gr Prof. Philip Kitchen Brock University, Faculty of Business Niagara Region pkitchen@brocku.ca Dr. Athanasios Krystallis Aarhus School of Business, Denmark ATKR@asb.dk Dr. Ong Fon Sim Graduate School of Business, Universiti Tun Abdul Razak, Kuala Lumpur ongfonsim@gmail.com Dr. Maria Palazzo University of Bedfordshire, UK info.mariapalazzo@alice.it Dr. Polyxeni (Jenny) Palla Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece jennypalla80@ymail.com Dr. Anastasios Panopoulos University of Western Macedonia apanopoulos@uowm.gr Dr. Athanasios Poulis Department of Business Administration, Athens University of Economics and Business, Greece tpoulis@aueb.gr Prof. Alfonso Siano Department of Communication Sciences, University of Salerno, Italy alfonsosiano@tin.it Dr. Prokopis Theodoridis University of Western Greece ptheodo@cc.uoi.gr Dr. Rodoula Tsiotsou

Assistant Professor of Services Marketing, Department of Marketing & Operations Management, University of Macedonia, Greece rtsiotsou@uom.gr Dr. Cleopatra Veloutsou Senior Lecturer in Marketing, Glasgow Business School, University of Glasgow, UK Cleopatra.Veloutsou@glasgow.ac.uk Prof. Prodromos Yannas Technological Educational Institution (TEI) of Western Macedonia yannas@kastoria.teikoz.gr Dr. Anna Zarkada Department of Business Administration, Athens University of Economics and Business azarkada@aueb.gr Prof. Yorgos Zotos Cyprus University of Technology, Faculty of Applied Arts and Communication, Department of Communication and Internet Studies, Cyprus, yorgos.zotos@cut.ac.cy, zotos@econ.auth.gr 15

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications 16

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications Interactive Marketing and Corporate Communications

17

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications The Impact of IMC in Virtual Communities on Brand Strategy for Universities

Philip J. Kitchen Brock University, Canada and ESC Rennes Business School, France pkitchen@brocku.ca B. Zafer Erdogan Bilecik University, Turkey Tolga Torun Bilecik University, Turkey The emergence of Integrated Marketing Communications (IMC) has become a signific ant example of development in the marketing discipline. It has influenced thinking a nd acting among all types of companies and organizations facing the realities and complexity of competition in a global economy (Holm 2006). The starting point on IMC was bundling promotion mix elements together to create the on-voice phenomenon. But IMC approaches have since grown in dimensionality and sophistication and have become essential in modern marketing (Schultz, Patti and Kitchen 2011; Kitchen et al. 2004). IMC has thus become widely accepted, pervaded various levels within businesses, and become an integral part of brand strategy (Sreedhar et al. 2005). Hence there is a now strong relationship between brand strategy and IMC. Both these have been influenced by the growth of the Internet (Kitchen and Panopoulos 2010). Nowadays, among the younger generation and also adults, it is very popular to vi sit Internet and have an account on or in social networking sites as known as virtual communities (Nielsen 2010). According to Stutzman s (2006, 1-7), Facebook is the most popular social networkin g site which 78% of users prefer with 55% expressing preference for MySpace (Hargittai 2007). In the global arena international and national universities are acting like for profit companies. They are very competitive. They also engage in widespread use of virtual communi ties to reach young people and in considering students as customers. Thus, taking part in virt ual communities represents a significant opportunity for the graduate education sector. In these respects, usage of integrated communication approaches by in relation t o virtual

communities, may affect student behaviour. For example, internalization (adoptio n of a university s values) (Bagozzi 2002) may impact upon satisfaction which in turn aff ects brand strategy. This paper will explore the impact of IMC in virtual communities on in relation to brand strategy. Initially, this begins with a rigorous conceptual overview, to be followed by a dual phase approach to gathering empirical data. The eventual importance of the study lies in providing depth knowledge on relationship between IMC and brand strategy in virtual commun ication using graduate education as the preferred foci for empirical research. References Bogazzi, Richard P. and Dholakia, Utpal M. 2002. Intentional Social Action in Vi rtual Communities. Journal of Interactive Marketing 16(2): 2-21. Hargittai, Eszter. 2007. Whose Space? Differences Among Users and Non-users of S ocial Network Sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communications 13(1):http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol13/issue1/hargittai.html Holm, Olof. 2006. Integrating Marketing Communication: From Tactics to Strategy. Corporate 18

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications Communications: an International Journal 11(1): 23-33. Kitchen, Philip J.; Brignell, Joanne; Li, Tao; & Spickett-Jones, Graham. 2004. E mergence of IMC: A Theoretical Perspective. Journal of Advertising Research: 19-30. Kitchen, Philip J. and Panopoulos, Anastasios. 2010. Online Public Relations: Th e Adoption Process and Innovation Challenge, a Greek Example. Public Relation Review 36: 222-229. Nielsen/Netratings, http://www.nielsen-online.com/pr/pr_060511.pdf. 01.10.2010. Schultz, Don, Patti, Charles, Kitchen, Philip J. 2011. The Evolution of Integrat ed Marketing Communications: The Customer-driven Marketplace, Routledge 1 Edition. Sreedhar, Madhavaram, Badrinarayanan, Vishag, Mcdonald, Robert E. 2005. Integrat ing Marketing Communication (IMC) and Brand Identity as Critical Components of Brand Equity Strategy: a Conc eptual Framework and Research Propositions. Journal of Advertising 34(4): 69-80. Stutzman, Frederic. 2006. An Evaluation of Identity-Sharing Behavior in Social N etwork Communities. IDMAa Journal 3(1): 1-7. 19

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications Gender differences in the interpretation of a Museum s web atmosphere. A Selectivity Hypothesis Approach

Eirini Tsichla Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Department of Business Administration, Gre ece, eirini_tsichla@yahoo.gr Leonidas Hatzithomas Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Department of Business Administration, Gre ece, leonidasnoe@yahoo.gr Christina Boutsouki Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Department of Business Administration, Gre ece. chbouts@econ.auth.gr Abstract This paper investigates the web atmosphere and consumer attitude interface. Onli ne environmental stimuli, conceived as high task relevant and low task relevant cue s, were manipulated employing an experimental design so as to assess their impact on att itude towards the website as well as attitude toward the brand. Similarly to expectations, low task relevant cues seemed to enhance both dependent variables of the study. Furthermore, the f indings suggest that gender exerts a moderating effect on the relationship between onlin e atmospherics and brand attitude: More specifically, on the absence of low task relevant cues, males developed less favourable attitude toward the brand while females attitude was consistent i n both experimental conditions. The particular differences are interpreted from a Selec tivity Hypothesis viewpoint, which attributes gender differences to differences in information pro cessing. Hence, the study supports the applicability of the Selectivity Hypothesis in the intern et context and propounds its relevance concerning brand attitude development.

Introduction Nowadays, the internet has managed to establish itself as a valuable everyday in formation and communication tool. The rapid development of virtual contexts for either commerc ial or communication purposes motivated practitioners to attentively develop and mainta in their online presence. Towards this end, web atmospheric elements have been excessivel y manipulated as a means to create an effective web design, capable of satisfying the organisation s marketing objectives while at the same time attracting surfers inter est. Web atmospherics are defined as the conscious designing of web environments to cr eate positive affect and/or cognitions in surfers in order to develop positive consum er responses (Dailey 2004, 796). For Milliman and Fugate (1993, 68), a web atmospheric cue is comparable to a brick-and-mortar cue and is described as any web interface component within an individual s perceptual field that stimulates one s senses . According to Eroglu, Machleit and Da vis (2001) although the online atmosphere lacks the tactical and olfactory cues of the offl ine store environment, the online retailer can manipulate the visual cues (and, to a limit ed extent, auditory cues) so as to produce affective reactions in site visitors, provide in formation about the retailer and influence shopper responses during the site visit. The pertinent li terature 20

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications acknowledges the importance of attractive web design in the enhancement of the s hoppers online experience (Woflinbarger and Gilly 2003; Wu, Cheng and Yen 2008; Ganesh e t al., 2010). Szymanski and Hise (2000) postulate the influence of site design and merchandisi ng on customer attraction and their satisfaction with Internet shopping while Ganesh et al. (20 10) found that many web surfers are motivated to conduct online shopping activities because of the stimulation effect of interesting websites. The tremendous potential of the new medium regarding the pursuit of marketing communications goals has fuelled considerable academic attention. A sound litera ture on web atmospherics has been developed, documenting their relationship with consumer pl easure and arousal, satisfaction, purchase intentions and urge to recommend the site to oth ers (for a review see Manganari, Siomkos and Vrechopoulos 2009). However, the content of the major ity of the existing studies seems rather dimensional, as it strives to investigate the envi ronmental stimuli in online store milieus. As a consequence, virtual service settings remain relat ively unexplored. Few exceptions include Rafaeli and Pratt (2005) and Hopkins et al. (2009) who fu rther attempt to amplify the relationship between web site design and the services marketing l iterature, suggesting that the internet itself can be conceived as a service and an organiz ation s website as an e-servicescape . The extensive focus on the online store context bears another implication as far as the studies dependent variables are concerned. The use of online retailer websites enabled t he elucidation of the web atmospherics influence on attitude toward the retailer (Eroglu et al. 2003; Fiore, Jin and Kim 2005) but their impact on attitude toward individual brands-and even mor e, service brands-is still not crystallized. Given the vital importance of online branding in the highly competitive contemporary marketplace (Ibeh, Luo and Dinnie, 2005), the particula r research gap should no longer remain unaddressed. Additionally, although gender differences in the internet context have been stud ied with respect to web advertising perceptions (Schlosser et al., 1999; Venkatesh and Morris, 20 00; McMahan, Hovland and McMillan 2009), use patterns (Wells and Chen 1999; Weiser, 2000; For d, Miller and Moss, 2001; Roger and Harris, 2003; Hupfer and Detlor, 2006), online privacy con cerns (Sheehan, 1999) and risk perceptions (Garbarino and Strahilevitz, 2004), the exi sting literature remains almost silent concerning the possible moderating effects of gender with

respect to the interpretation of web atmospheric stimuli. This is surprising taking into consid eration the interdisciplinary acknowledgment of differences in information processing betwee n men and women. These differences may result in non similar evaluations of verbal and vis ual stimuli which, in turn, may impact on their attitude development. The present study attempts to add to the scant literature of gender differences in the internet context, and the interpretation of the web atmosphere in particular. A virtual s ervicescape and more specifically a Museum website was chosen as the basis of an experimental de sign, following Fortin and Ballantine s (2009) advice on the perfect suitability of expe riments for the study of online environments. The purpose of the research is twofold: Firstly, t o elucidate the influence of web atmospherics on attitude toward the website as well as attitude towards the brand. Secondly, it attempts to investigate the potential moderating effect of g ender with respect to the above brand associations. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: The next section juxtapose s the theoretical background that informs the development of the proposed model of the study. Next , the analytic procedure that was followed during the conduction of the experiment is thoroughly explained. The subsequent section displays the empirical results of the study, f ollowed by an interpretive discussion that explains their value and highlights their contribut ion to the relevant literature. Managerial implications are drawn for practitioners who are interest ed in ameliorating their web presence. Finally, the study s limitations are acknowledged , and fruitful areas for further inquiry are suggested. 21

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications Theoretical background and hypothesis development Web atmospherics Kotler (1973, 50) was the first to introduce the term atmospherics as the conscious designing of space to create certain buyer effects, specifically, the designing of buying environments to produce specific emotional effects in the buyer that enhance purchase probabilit y . As soon as the notion of atmospherics was adapted from the physical settings to the virtual m arketplace, academic interest was directed towards the conceptualization of the particular e nvironmental cues that were applicable to the new medium along with the exploration of their potential impact. A highly influential typology was the one suggested and thereafter empir ically tested by Eroglu, Machleit and Davis (2001; 2003) who distinguish online atmospherics betw een high task relevant and low task relevant cues. According to their taxonomy, high task rele vant cues include all the site descriptors (verbal or pictorial) that appear on the screen which fa cilitate and enable the consumer s shopping goal attainment such as descriptions of the merchandise, th e price, the terms of sale, delivery and return policies, pictures of the merchandise and navigation aids. Low task relevant cues refer to site information that is relatively inconsequenti al to the completion of the shopping task (Eroglu, Machleit and Davis, 2001 p. 180) and inc lude colours, borders and background patterns, typestyles and fonts, animation, music, enterta inment, pictures other than the merchandise etc. Low task relevant cues appear to create an atmosphere that has the potential to make a pleasurable experience and trigger m emories of a brick-and-mortar setting rather than directly affecting the completion of the ta sk (Eroglu, Machleit and Davis, 2001). Another popular conceptualization considers four variables pertaining to web atm ospherics: structure, effectiveness of its content, informativeness and entertainment (Bell and Tang, 1998; Chen and Wells, 1999; Richard, 2005). Structure and refers to the virtual store layout

according to Huizingh (2000) it could be a tree, a tree with a return-to-home pa ge button, a tree with horizontal links, and an extensive network. Effectiveness of information con tent pertains to currency of the information content of the website. Informativeness encompasses

the amount as well as the richness of the information the website displays, and tainment

enter

encompasses sensory and hedonic elements such as color, music, action, pictures, graphs, videos and interactivity. Richard (2005) connects the two typologies arguing tha t structure, effectiveness of the information content and informativeness belong to the high task relevant cues while entertainment is the sole dimension of the low task relevant cues. Th is study will utilize the Eroglu, Machleit and Davis typology (2001) as it been widely tested and supported (e.g. Eroglu, Machleit and Davis 2003; Ha and Lennon, 2010). This classification of web atmospherics into two categories facilitates their unambiguous manipulation and ideally suits the needs of the 2 X 2 full factorial design effectuated in the study. Hence the following conceptual framework is developed, schematically illustrated in Figure 1. The th eoretical grounding of the emergent research hypotheses is thoroughly explained as follows . 22

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications Figure 1: The proposed model for the study Attitude toward the site ions are is considered a useful variable as far as website evaluat

concerned and has a positive impact on attitudes towards the advertisement, bran d attitudes and purchase intentions (Stevenson, Bruner and Kumar 2000; Dodds, 1991). The per tinent literature has drawn parallels between online atmospherics and attitude towards the site (Childers et al. 2001; Coyle and Thorson, 2001). The importance of entertainment with respect to website evaluations and attitude toward the site has also been reported (Duco ffe, 1996; McMillan et al. 2003; Richard, 2005, Richard et al. 2009). Childers et al. (2001 ) argue that the more immersive, hedonic aspects of the new media play an equal role along the ins trumental aspects as predictors of online attitudes. Visual attractiveness was found to be a primary indicator of overall impression and website preference (Schenkman and Jonsson, 2 000). Moreover, significant changes in attitudes were observed when subjects were expo sed to versions of a website that only varied in low task relevant cues (Mandel and Joh nson, 2002; Eroglu et al., 2003). Consequently, it can be hypothesized that: H1: Low task relevant atmospheric cues will exert a positive effect on attitude toward the website The website might create a link between the consumer interaction and the brand, likely better than traditional advertising media can, and sustain a relationship and positive feeling with a brand (Dahlen, Rasch, and Rosengren 2003). The relevant literature provides some evidence that factors pertaining to low task relevant cues are related to consumers brand attit udes. Form, as far as technical issues and content, has been found to enhance the total brand e xperience (Schenkman and Johnsson 2000; Lavie and Tractinsky 2004). Wang, Minor and Wei (2 010) argue that consumers cognitive, affective and conative outcomes can be significantly ev oked by web aesthetic elements. Schlosser (2003) postulates object interactivity to be an an tecedent of brand attitudes. In a services context, due to intangibility, the online experience mi ght be of significant importance in forming brand attitudes: Rafaeli and Pratt (2005) suggest that the

virtual servicescape may be critical as it constitutes the key artifact representing the organization to consumers. It seems reasonable then to expect an influence on brand attitude as well. Therefore, it could be hypothesized that a website displaying both high task rel evant and low task relevant atmospheric stimuli is likely to reinforce more favourable brand a ttitude than a website which lacks low task relevant cues. Hence: H2: Low task relevant atmospheric cues will exert a positive effect on attitude toward the brand 23

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications Gender differences The role of potential moderating effects on the relationship between online atmo spherics and consumers attitude seems to be of great interest, taking into consideration that websites, just like physical products and services are usually targeted to specific segments of the market. Nonetheless, it has also been argued that hypothesizing direct effects may be so mewhat obvious and it is more meaningful to investigate moderating effects of external factors such as consumer and situational characteristics (e.g. Baron and Kenny, 1986; Ajzen, 1991). According to Putrevu (2001) gender is frequently used as a basis for segmentatio n for a significant proportion of products and services. Such segmentation, meets severa l of the requirements for successful implementation: It defines segments easy to identify , easy to access, and large enough to be profitable. Traditionally, certain personality traits hav e been ascribed to either men or women and empirical research has documented various differences: H olbrook (1986) revealed that gender showed a significant tendency to moderate the effect s of features on evaluative judgments and thereby to serve as meaningful source of heterogenei ty in preference structure. Men, due to their frequent conceptualization of items in t erms of physical attributes and objective states, have been portrayed as more analytical and logi cal in their processing orientation. In contrast, women have been characterized as more subje ctive, interpretive and intuitive as they indulge in more associative, imagery-laced in terpretations (Haas 1979). Women seem more accurate in decoding nonverbal cues (Hall 1984; Eve rhart et al. 2001) and they have been found to show greater sensitivity to a variety of situa tion specific cues in determining their self-evaluations (Lenney, Gold and Browning 1983). Biology, Socialization Theory and information processing style offer possible ex planations for gender differences observed in consumer responses. Biology suggests that the ori gin of these differences lies in brain hemispheric lateralization. According to Hansen (1981) the human brain is divided into two hemispheres: The left hemisphere specializes in verbal abili ties whereas the right specializes in spatial perception. Empirical evidence documents that the t wo hemispheres are more integrated in females and more specialized in males (Everhart et al. 20 01; Saucier and Elias 2001). Consequently, more functionally lateralised male brains process inf ormation on a piecemeal basis, whereas more integrated female brains process information holis

tically. Men are thus likely to prefer highly focused information along a few key attributes while women may be more attracted to information-rich sources (Richard et al. 2009). The socialization literature claims that gender role identification holds a corn erstone position in the development of gender differences. Males are considered to pursue agentic go als due to their self-assertive and achievement orientation whereas females pursue communal goals, being driven by interdependent and interpersonal concerns (Bakan, 1966; Eagly, 1987). This assertion seems as a precursor to the development of Item-specific versus Relational proces sing theory (Einstein and Hunt 1980) that claims the existence of two types of elaboration. The first is called relational processing and emphasizes similarities or shared themes among dispara te pieces of information. The second type, item specific elaboration, stresses attributes tha t are unique or distinctive to a message. As men are driven by agentic goals they are more likel y to attend to message claims that affect them directly, engaging in item-specific processing. On the contrary, women due to their communal orientation tend to consider all aspects of the mess age, undertaking relational processing (Putrevu, 2001). More recently Meyers-Levy and her colleagues (Meyers-Levy 1989; Meyers-Levy and Maheswaran 1991; Meyers-Levy and Sternthal 1991) developed a Selectivity Hypothe sis proposing that the origin of gender differences lies in differences in depth of processing. More specifically, men are considered as to be driven by selective processors , as they are more likely

overall message themes and rely on efficiency-striving heuristics in spite of de tailed message elaboration. Heuristic processing is conceived as a limited processing mode that demands much 24

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications less cognitive effort and capacity than systematic processing. When processing h euristically, people focus on that subset of available information that enables them to use si mple inferential rules, schemata, or cognitive heuristics to formulate their judgements and decis ions (Chaiken, Liberman and Eagly, 1989). On the contrary, the Selectivity Hypothesis regards women as comprehensive or syste matic processors . Systematic processing is conceived as an analytic orientation on whic h perceivers access and scrutinize all informational input for its relevance and importance t o their judgement task, and integrate all useful information in forming their judgements (Chaiken, Liberman and Eagly, 1989). Therefore, females are more likely to engage in effortful elaborat ion of the message content, attempt to extensively elaborate on more message claims than me n and give equal weight to self-generated and other-generated information. Meyers-Levy and Sternthal (1991) further attest that females possess a lower threshold for elaborating on message cues, and may have greater access to the implications of those cues at judgment. Conse quently, apart from considering highly available, objective attributes, females may elaborate o n message cues that command a limited amount of attention. Thus they are able to consider non o bservable conditions or subjective considerations that may more thoroughly explain that wh ich is readily discernible (Meyers-Levy 1989). The selectivity model has been widely attributed to explain the detection of gen der differences regarding advertising response (e.g. Carsky and Zuckerman 1991; Darley and Smith , 1995) as well as online consumer behavior. More specifically Rodgers and Harris (2003) as cribed their finding that women seem to perceive less emotional gratification from online sho pping than men and report lower levels of trust to the selectivity hypothesis, since female s are supposed to rely on details and intricacies and might very well affect how they feel about a particular website. Ford and Miller (1996) reported gender differences in Internet searchin g, as men appeared to enjoy browsing and women appeared disappointed and disoriented by th e internet. In a later study Ford, Miller and Moss (2001) associated information retrieval w ith men and information failure with women. These findings were accommodated within the sele ctivity model, as the comprehensive processing of women might have prevented them from a voiding unnecessary information while men s selective processing could have facilitated th eir

concentration on the appropriate information. In addition, Richard et al. (2009) findings indicate that males preferred straightforward information presented in a well structured website due to their selective processing, whereas female comprehensive orientation urged them to more exploratory behavior and greater involvement with the website content. Since attitude development is conceived as a function of incremental information al input (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975: 275) the adoption of a selectivity model viewpoint may reasonably hypothesize that differences in information processing strategies will lead to v ariations concerning male and female attitude toward the website along with attitude towar d the brand. Since men s threshold for elaborate processing is higher than women it is anticipa ted that a web atmosphere that lacks low task relevant cues will fail to exceed their threshold and as a result the stimuli will be processed schematically. As the cornerstone of heuristic pro cessing is the idea that specific rules, schemata, or heuristics can mediate people s attitude (or oth er social) judgments (Chaiken, Liberman and Eagly, 1989) the schema based processing is exp ected to generate lower attitudes toward the site. On the opposite, women s lower threshold is expected to be exceeded even in the presence of high task relevant cues alone and thus, f avourable attitudes toward the website may be evoked. Hence, it is hypothesized that: H3: Gender will have a moderating effect on the relationship between online atmo spherics and attitude toward the website Moreover, in the light of the Selectivity Hypothesis it is expected that males he uristic processing will influence their attitude toward the museum brand, in a manner that attitude would be largely dependent on the web atmosphere they were about to encounter. As men won t be 25

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications likely to elaborate on other information stimuli before rendering judgements, in the both high and low task relevant cues condition men might report higher attitude toward the brand whereas in the condition displaying only high task relevant cues their attitude might be less favorable. Instead, females are anticipated to consistently value both websites since their detailed elaborating style would be satisfied from the informational character o f the high task relevant cues, present in both conditions. Therefore: H4: Gender will have a moderating effect on the relationship between online atmo spherics and attitude toward the brand Methodology In order to collect the data for the study, the website of a Museum was selected . The particular virtual servicescape was considered suitable, taking into consideration its pure ly informative and educational function that does not entail e-shopping opportunities. Consequently , common issues pertaining to online transactions such as pricing, financial security con cerns, delivery policies and merchandise information are eliminated, leaving a fertile ground fo r the exploration of the relationship between environmental stimuli and consumer brand perceptions . In a museum website, it is evident that the goal attainment of the visitors is to inf orm and educate themselves rather than to perform shopping activities. In this case, it is presu med that the high task relevant cues consist of information in the form of text and pictures refer ring to the museum s exhibitions, particular artifacts, and educational programmes. The websites A laboratory experiment was conducted in order to fulfill the purpose of the res earch. The actual website of the Archeological Museum of Thessaloniki was chosen as the context of the study, the web atmospherics of which were manipulated by the webpage designers so as to create two slightly modified special site versions. According to the suggestion of Stevenso n, Bruner and Kumar (2000) the use of a real webpage was employed in order to improve the ecol ogical validity of the study, instead of creating a fictitious one. In both versions, h igh task relevant cues were identical: The introduction page presented the title as well as an exterior photograph of the Museum. The homepage displayed a picture of the Museum s interior and the site

menu directed the visitor to

Permanent Exhibitions ,

Temporary Exhibitions , News and Events , sub-menus. Finally, an array of butto Sitemap sections.

Educational Programmes , Publications and ns enabled the user to access the Contact Us , The

Archive

Visitor Information , and

manipulation concerned the low-task relevant cues: Version A was enriched with m usic, displayed a light blue colour background and fonts (instead of white), added a p hotograph on the main section of the homepage as well as some frames and background patterns, incorporated more vivid photos of the museum exterior and exhibitions, and five animated graphics replaced static pictures on several sub menus of the webpage. Finally, the text descriptions regarding the permanent m and temporary exhibitions sections of the museu

website were complemented with virtual reality tours. On the contrary, Version B was designed on a white background with black fonts, displayed museum photos and text descrip tions and contained no music, virtual tours or animation. Research Sample A total sample of 68 undergraduate students (20 males and 48 females) enrolled i n Marketing courses from the School of Economics, Department of Business Administration of t he Aristotle University of Thessaloniki participated in the study. As a result, groups were s imilar in terms of 26

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications age and educational backgrounds. Each version of the webpage was viewed equally by 34 subjects. The assignment of the participants to the groups was conducted randoml y. Procedure The experimental sessions took place in a campus computer laboratory. The person al computers that were used in the procedure possessed exactly the same technical characteris tics, screen resolution and speakers, ensuring that all respondents would experience the webs ite stimuli facing identical conditions. Each student was assigned individually to a persona l computer, and received instructions to browse the particular version of the webpage for fiftee n minutes, in order to assure that he or she they wouldn t give up viewing the webpage, but adeq uate time would be available in order to form attitudes and perceptions. After the complet ion of the timeline, participants were instructed to complete a questionnaire. Measures The questionnaire contained several attitude scales. Respondents attitude toward the site was measured with the 6-item scale proposed by Chen and Wells (1999). Attitude towar d the brand was measured with the three following items: favorable/unfavorable , like/dislike positive/ negative . Additionally, involvement was measured using the six-item Laur ent and Kapferer s scale (1985) which operationalises the construct as two dimensional: pr oduct-class involvement and purchase intention involvement. All variables were measured usin g five point Likert scales. Respondents were also asked to indicate whether they had visited the Museum before and whether they had previously encountered the webpage. Finally, gender information was collected. The questionnaire was pilot tested on an experiment with 14 postg raduate students, using with the same conditions as the actual experiment. Research Findings To test the four hypotheses of interest a factorial multivariate analysis of cov ariance (MANCOVA) was conducted with online store atmospherics (a website that contained both low and high task relevant cues and a website that contained only high task relevant cues) and gender as the independent variables and attitude toward the site along with atti tude toward the (museum) brand as the dependent factors. In addition, to explore further the pre and

cise nature of interactions, two separate, factorial analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were unde rtaken. MANCOVA and ANCOVAs were chosen as appropriate statistical procedures for identi fying the effects of the dichotomous independent variables on the continues dependent vari ables (Tabachnick and Fidell 2001). We calculated the average of the ratings for each scale, because their internal reliability, as measured by Cronbach s Alpha, satisfied Nunnally's (1978) criterion of 0.7. Particularly, Cronbach s alpha coefficient of reliability was .82 for atti tude toward the site, .77 for the attitude toward the museum brand, .84 for product class involvement and .78 for purchase decision involvement. Covariates Product class involvement and purchase decision involvement (Laurent and Kapfere r s scale 1985; Mittal 1989) were used as covariates for the MANCOVA and for the two ANCOV As, since many prior studies have stressed the important role of product involvement in at titude toward the web site and attitude toward the brand (Elliott and Speck 2005; Koufaris 200 2; McMillan 2000; McMillan 1999; Ognianova 1998). In that manner, the present study assessed the 27

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications interactive effects of online environmental cues and gender on attitudes, adjust ing simultaneously for differences in product involvement (Tabachnick and Fidell 200 1). Both MANCOVA and separate ANCOVAs indicated no effect of product class involvement an d purchase decision involvement on the attitude toward the site and attitude towar d the museum (Table 1). Table 1: Effects of Low Task Relevant Atmospheric Cues and Gender on Attitude toward Site and Attitude toward the Brand Multivariate Effects Univariate Effects Independent Variables Wilks F-Value df Attitude df Attitude Lambda toward toward the site the brand Covariates Product class involvement .979 .646 1 1.20 1 1.11 Purchase decision .997 .091 1 .169 1 .55 involvement Main Effects Online environmental cues .896 3.55 1 6.78* 1 5.81* Gender .922 2.57 1 4.20* 1 .84 Interactions Online environmental cues .921 2.60 1 2.79 1 5.26* * Gender *p<.05 Attitude toward the site The MANCOVA, showed a significant main effect of online environmental cues on at titude toward the site (F=6.78, p<.012) (Table 1). It appears that exposure to low task relevant atmospheric cues is associated with more positive attitude toward the site (M=3. 72, SD=.56, mean for high task relevant cues=3.42, SD=.75) (see Figure 2). Thus, hypothesis 1 is supported. Besides, there was a significant main effect of participants gender on attitude t oward the site (F=4. 20, p<.044) with females (M=3.65, SD=.58) reporting more positive attitude scores than males (M=3.37, SD=.85). Hypothesis 3 posited that gender has a moderating effect on the relationship bet ween online environmental cues and attitude toward the site. However, neither MANCOVA (F=2.7 9, p<.10) nor ANCOVA (F=2.78, p<.10) found any evidence of moderation. Only the analysis o f simple effects of online atmospheric cues at each level of gender indicated that males were significantly more likely to formulate positive attitude toward the site (F=6.91, p<.018) when exposed both to low and high task relevant cues (Mean=3.68, SD= .64) than when exposed only to h

igh task relevant cues (Mean=2.92, SD=.95) (see Figure 1). Thus hypothesis 3 receives onl y weak support. Attitude toward the brand Similarly, the MANCOVA supported a main effect of online atmospheric cues on att itude toward the museum brand (F=5. 81, p<.019) (Table 1). It seems that participants created more positive attitude toward the brand when exposed both to low and high task relevant cues ( M=3.80, SD=.70) than when exposed only to high task relevant cues (M=3.52, SD=.75). Thes e findings are consistent with hypothesis 2. As expected, MANCOVA revealed an interaction effec t between online environmental cues and gender in attitude toward the brand (F=5.26, p<.02 5). Males had significantly more positive attitude toward the brand in the presence of low tas k relevant cues. On the contrary, low and high task relevant cues produce similar levels of attit ude toward the 28

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications brand in female group (see Figure 2). ANCOVA resulted in the same finding as tha t obtained with MANCOVA (F=5.26, p<.025). Thus, hypothesis 4 is supported. Figure 1: Effects of Low Task Relevant Atmospheric Cues and Gender on Attitude toward the Site

29

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications Figure 2: Effects of Low Task Relevant Atmospheric Cues and Gender on Attitude toward the Brand

Discussion The research findings yield important insights regarding the under researched ro le of web atmospherics on virtual servicescapes. Particular effects of high task and low t ask relevant cues on consumer brand associations are highlighted and the moderating effect of gend er is unfurled. The study findings provide support to H1, indicating that low task relevant cues may enhance attitude toward the website. Consequently, the enrichment of a webpage with fact ors that augment its entertainment value positively influences surfers attitude toward the site itself. The above finding is congruent with Rowley (2002) who claims that images including b oth static and kinetic graphics can make a web site page look more interesting. Furthermore, it aligns with relevant research reflecting the idea that the internet as a medium is not used for utilitarian purposes alone; rather, it increasingly serves consumers iding a blend hedonic motivations prov

of entertaining and recreational experiences (Childers et al, 2001; Ganesh et al ., 2010). As H2 attests, low task relevant atmospheric cues exert a positive effect on att itude toward the brand. The analysis of the findings denote that subjects who viewed the version of the website that contained both low task and high task relevant cues were keen to develop mo re favorable attitude toward the museum brand than participants who encountered the website t hat displayed solely high task relevant cues. The above assertion is in accordance w ith Keller s (2009) view which considers interactive marketing communications able to encourage atti tude formation and decision making, especially when combined with off-line channels. Their potential to deliver sight, sound and motion of all forms, -in that case reinforced by the low task relevant cues-facilitates the creation of impactful experiential and enduring feelings. However, the study s most salient contribution lies on the revelation of the moder ating effect of gender on the relationship between online atmosphere and attitude toward the bra nd, lending support to H4. The experimental evidence suggests that males who were instructed

to view the website that displayed only high task relevant cues formulated less favorable at titude toward the brand than males who viewed the webpage where low and high task relevant cue s co existed. Interestingly, females manifested similar attitudinal responses towards the brand, no matter which version of the website they had encountered. This finding can be interpreted from a Selectivity Hypothesis viewpoint. The mod el theorizes that men are selective processors who tend to focus on a subset of salient and r eadily available cues, overall message themes and schemas with the goal to use efficiency-strivin g heuristics. Hence, in the particular case it seems that males heavily relied on the stimuli they have just been 30

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications exposed to during the experiment, and developed their evaluative judgments accor dingly. The webpage that displayed a source of available cues might have served as heuristic s in the process of brand attitude development. Consequently, the presence of high task relevant cues alone led males to evaluate the Museum brand in a less favorable way while the incorporati on of the webpage with low task relevant cues enhanced their attitudes of the Museum brand . Moreover, it appears that in the absence of low task relevant cues, men s threshold failed t o be exceeded resulting in lower brand attitude while the existence of both web atmospheric di mensions managed to overleap their threshold, stimulating higher attitude. On the contrary, females, who according to the selectivity hypothesis are consid ered to engage in more detailed message content elaboration and to encode more message claims i n a more extensive manner, appear not to be dramatically affected by the virtual atmosphe re in order to develop their attitudes toward the museum brand. Since they are regarded as more sensitive to a variety of situation-specific cues in rendering judgments, it seems logical to assume that unlike males, they assimilated other stimuli apart from the web atmospherics. These ext ernal cues could include information they have been exposed to previously (such as past exp erience, word of mouth, marketing communication claims) and seem to receive equal weight along with the virtual servicescape. As a consequence, the evaluations of the female participan ts of both experimental groups resulted in consistent responses with respect to their attit udes toward the museum brand. Similarly, the upheld of H4 seems to support that the specialized hemispheric pr ocessing by men might require nonverbal reinforcement in the form of pictures, graphs, music etc (the low task relevant cues that were manipulated in the current study) of the verbal product information (Putrevu 2001) contained in marketing communications. Females, on the other hand are considered to prefer more verbally and visually rich information stimuli, since they ideally accommodate their elaborate processing nature. Thus, is appears that the informa tional value of the high task relevant cues satisfied the effortful elaboration processing of wo men and thus did not contribute to less favorable brand evaluations. Nevertheless, as far as male s are concerned, the absence of visual reinforcement might have been critical for their reported less favorable attitudes.

The empirical findings of the study lend only weak support to H3. Gender failed to exhibit a moderating effect no matter simple effects of web atmospheric stimuli were found to instigate consistent attitudinal responses, in a manner that low task relevant cues led to more favourable attitude toward the site. Interestingly, however, women reported more favourable attitude toward the website compared to men. This unexpected result is congruent with Ric hard et al. (2009) and could be explained in the context of gender differences in the intern et use patterns which, in turn are accommodated within the Selectivity framework. Their study in dicates that since women are more likely to use websites for enjoyment and information gather ing, they were likely to value the effectiveness and entertainment value of such informati on and engage in more exploratory behavior. Consequently, our study suggests that females are keen to formulate stronger and more favourable responses than men, who tend to approach information on a piecemeal manner and limit their information gathering to cues that are immediately relevant to the current context. (Richard et al., 2009). 31

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications Managerial Implications This study may contribute to a better specification of the parameters that marke ting practitioners should emphasize so as to optimize their internet presence. Taking into consideration that the online atmospheric stimuli, apart from influencing surfer s attitude toward the site may decisively shape brand attitude as well, especially as far a s male consumers are concerned, it is reasonable to argue that an effective web design grows in i mportance and should receive adequate attention. In addition, as Vilnai-Yavetz and Rafaeli (20 06) argue, the initial first impression effects of the physical servicescapes are of particular i mportance for the e-services context, as costs of transfer from one setting to another are much lo wer, not to mention easier and quicker. As far as gender is a common segmenting factor for a plentitude of products and services and thus a website could possibly target either of the two, the insights of this stu dy could inform the development of such websites. The Selectivity Hypothesis implies that men as heu ristic processors would benefit from marketing communications stimuli that are simple a nd focus on a single theme while at the same time the verbal information should be reinforced with non verbal, visual stimuli (Putrevu, 2001). Thus, websites targeted to men should be enriched with low task relevant cues such as music, pictures, graphs and animation that align with the concrete verbal information. On the contrary, websites targeted to women should ideally i ncorporate both low task and high task relevant cues, but attention should be paid on the l evel of richness of the information displayed, and on its highly informative nature that satisfie s their detailed elaboration processing. Limitations and Further Research The generalisability of the research findings should be considered with caution due to the smallsized, convenience student sample used for the collection of the data. Although convenience samples are suitable for theory testing (Calder, Phillips and Tybout, 1981) furt her research among a bigger and less homogeneous sample of consumers may seek to validate the generalisability of this study s findings. Moreover, the participants of the exper

iment were not equally comprised of men and women. Due to a greater attendance of women in the particular Marketing courses the sample was drawn from, and the voluntary nature of their p articipation it was impossible to establish an exact equal number of males and females. However, the pertinent literature provides evidence of studies exploring gender differences o r testing the selectivity hypothesis which did not employ an equal number of males and females (e.g. Rodgers and Harris 2003; Hupfer and Detlor, 2006; Richard et al. 2009) without negative influences on the quality of their results. Moreover, the study was context specific, as it was conducted using a Museum web site, as an example of a virtual servicescape. Consequently, future research could investiga te other service territories or physical products so as to gauge attitudinal responses provoked b y the online stimuli of their websites. Furthermore, it would be interesting to explore the r ole of web atmosphere in other brand associations such as brand personality, brand equity o r brand experience. Concluding Remarks The conceptual framework suggested in this study attempts to contribute to the k nowledge base of the web atmospherics by shedding some light on their role in consumers website and brand attitude formulation. The study s findings support the applicability of the Select ivity Hypothesis in the internet context and yields important insights concerning gender differen ces in attitude 32

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications development. Although a Selectivity Model standpoint has attempted to explain re ported differences in the online atmosphere (Richard et al. 2009) this is seemingly the first study to employ a Selectivity outlook regarding the relationship between web atmospheric stimuli and consumers References Ajzen, I. 1991. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Huma n Decision Processes 50: 179-211 Bakan, D. 1966. The Duality of Human Existence: An Essay on Psychology and Relig ion. Chicago: Rand Mcnally Publishing Company. Baron, R.M., and D. Kenny. 1986. The moderator-mediator distinction in social ps ychology research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psy chology 51: 1173-1182. Bell, H. and N.K.H. Tang. 1998. The effectiveness of commercial internet web sit es: a user s perspective. Internet Research 8, no.3: 219-228. Calder, B., L.W. Phillips, and A.M. Tybout. 1981. Designing research for applica tion. Journal of Consumer Research 8, no.2: 197-202 Carsky, M.L. and M.E. Zuckerman. 1991. In search of gender differences in market ing communication: An historical/ contemporary analysis. In Gender and Consumer Behavior, ed. J.A. Costa, Salt lak e City, UT: University of Utah Printing Press. Chaiken, S., A. Liberman, and A.H. Eagly. 1989. Heuristic and systematic informa tion processing within and beyond the persuasion context. In Unintended Thaught, ed. J.S. Uleman and J.A. Bargh, 212-2 52. New York: the Guilford Press Chen, Q., and W.D. Wells. 1999. Attitude towards the site. Journal of Advertisin g Research 39, no.5: 27-38 Childers, T.L., C.L. Carr, J. Peck, and S. Carson, 2001. Hedonic and utilitarian motivations for online retail shopping behavior. Journal of Retailing, 77: 511-535. Coyle, J.R., and E. Thorson. 2001. The effects of progressive levels of integrit y and vividness in web marketing sites. Journal of Advertising 30, no. 3: 65-77. Dahln, M., A. Rasch, and S. Rosengren. 2003. Love at first site? A study of websi te advertising effectiveness. Journal of Advertising Research 43, no.1: 25-33 brand attitudes.

Dailey, L.C. 2004. Navigational web atmospherics: Explaining the influence of re strictive navigation cues. Journal of Business Research 57, no.7: 795-803 Darley, W.K., and R.E. Smith. 1995. Gender differences in information processing strategies: An empirical test of the selectivity model in advertising response. Journal of Advertising 24, no.1: 41-5 6 Ducoffe R.H. 1996. Advertising value and advertising on the web. Journal of Adve rtising Research 36, no. 5: 21-35 Eagly, A.H. 1987. Sex differences in social behavior: a social-role interpretati on. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Laurence Erlbaum Associates Einstein, G.O., and R.R. Hunt. 1980. Levels of processing and organization: addi tive effects of individual-item and relational processing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Me mory 6, no.5: 588-598. Elliott M. T., and P.S. Speck. 2005. Factors That Affect Attitude towards a Reta il Web Site. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 13, no.1: 40-51. Eroglu, S.A., K.A. Machleit, and L.M. Davis. 2001. Atmospheric qualities of onli ne retailing: A conceptual model and implications. Journal of Business Research 54: 117-184. Eroglu, S.A., K.A. Machleit, and L.M. Davis. 2003. Empirical Testing of a Model of Online Store Atmospherics and Shopper Responses. Psychology & Marketing 20, no.2: 139-150. Everhart, D.E., J. L. Shucard, T. Quatrin, and D.W. Shucard. 2001. Sex-related d ifferences in event-related potentials, face recognition and facial processing in prepubertal children. Neuropsychology 15, no.3: 329-341 Fishbein, M., and I. Ajzen. 1975. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An I ntroduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Fiore, A.M., H. Jin, and J. Kim. 2005. For fun and profit: Hedonic value from im age interactivity and responses toward an online store. Psychology and Marketing 22, no.8: 669-694 Ford, N., and D. Miller. 1996. Gender differences in internet perception and use . In Papers from the Third Electronic Library and Visual Information Research (ELVIRA) Conference: 87-202. London: ASL IB Ford, N., D. Miller, and N. Moss. 2001. The role of individual differences in in ternet searching: An empirical study. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 52, no. 1 2: 1049-1066 Fortin, D.R., and P.W. Ballantine. 2009. Editorial: Why the experimental method is the i deal tool for studying

consumer research in online environments. Journal of Internet Marketing and Adve rtising 5, no. 4: 241-245. Ganesh, J., K.E. Reynolds, M. Luckett, and N. Pomirleanu. 2010. Online shopper m otivations, and e-store attributes: An examination of online patronage behavior and shopper typologies. Journal of Reta iling 86, no.1: 106-115 Garbarino, E. and M. Strahilevitz. 2004. Gender differences in the perceived ris k of buying online and the effects of receiving a site recommendation. Journal of Business Research 57, no.7: 768-774. 33

16th International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications Ha, Y. and S.J. Lennon. 2010. Online visual merchandising (VMD) cues and consume r pleasure and arousal: Purchasing versus browsing situation. Psychology and Marketing 27, no.2: 141-165 Haas, A. 1979. Male and Female Spoken Language Differences: Stereotypes and Evid ence. Psychological Bulletin 86: 616-626 Hall, J.A. 1984. Nonverbal sex differences: Communication Accuracy and Expressiv e Style. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. Hansen, F. 1981. Hemispheral Lateralization: Implications for understanding cons umer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research 1: 23-26 Holbrook, M. 1986. Aims, concepts and methods for the representation of individu al differences in esthetics responses to design features. Journal of Consumer Research 13: 337-347 Hopkins, C.D., S.J. Grove, M.A. Raymond, and M.C. Laforge. 2009. Designing the e -Servicescape: Implications for online retailers. Journal of Internet Commerce 8: 23-43. Huizingh, E. 2000. The content and design of websites: An empirical study. Infor mation Management 37: 123-134 Hupfer, M.E., and B. Detlor. 2006. Gender and web information seeking: A self-co ncept orientation model. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 57, no. 8: 1105-1115 . Ibeh, K., Y. Luo, and K. Dinnie. 2005. E-branding strategies of internet compani es: Some preliminary insights from the UK. Journal of Brand Management 12, no. 5: 355-373. Keller, K.L. 2009. Building strong brands in a modern marketing communications e nvironment. Journal of Marketing Communications 15, no.2-3: 139-155. Kotler, P. 1973-1974. Atmospherics as a marketing tool. Journal of Retailing 49: 48-64. Koufaris M. 2002. Applying the technology acceptance model and flow theory to on -line consumer behavior. Information System Research 13, no.2 : 205 223. Laurent, G. and J.-N. Kapferer. 1985. Measuring consumer involvement profiles. J ournal of Marketing Research 22, no.1: 41-53. Lavie, T., and N. Tractinsky. 2004. Assessing dimensions of perceived visual aes thetics of web sites. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 60, no.3: 269-298. Lenney, E., J. Gold and C. Browning. 1983. Sex differences in self-confidence: T he influence of comparison to others

ability level. Sex Roles 9: 925-942 Mandel, N. and E. Johnson. 2002. When Web Pages Influence Choice: Effects of Vis ual Primes on Experts and Novices. Journal of Consumer Research 29, no.2: 235-246. Manganari, E.E., G.J. Siomkos, and A.P. Vrechopoulos. 2009. Store atmosphere in web retailing. European Journal of Marketing 43, no.9: 1140-1153. McMahan, C., R. Hovland, and S. McMillan. 2010. Online marketing communications: Exploring online consumer behavior by examining gender differences and interactivity within internet adver tising. Journal of Interactive Marketing 10, no.1: 61-76. McMillan, S.J. 1999. Advertising Age and Interactivity: Tracing Media Evolution through the Advertising Trade Press. In Proceedings of the 1999 Conference of the American Academy of Advertising, ed. M . Roberts, 107-114. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida. McMillan, S.J. 2000. Interactivity is in the Eye of the Beholder. Function, Perc eption, Involvement, and Attitude Toward Web Sites. In Proceedings of the 2000 Conference of the American Academy of Advertising, ed. M.A. Shaver, 71 78. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University. McMillan, S.J., J.S. Hwang and G. Lee. 2003. Effects of structural and perceptua l factors on attitude toward the web site. Journal of Advertising Research 43, no. 4: 400-409. Meyers-Levy, J. 1989. Gender Differences in Information Processing: A Selectivit y Interpretation. In Cognitive and Affective Responses to Advertising, ed. Particia Cafferata and Alice Tybout, 219 -260. Lexington, MA: Lexington. Meyers-Levy, J. and D, Maheswaran. 1991. Exploring Differences in Males es Processing Strategy. Journal of Consumer Research 18: 63-70. and Femal

Meyers-Levy, J. and Sternthal, B. 1991. Gender Differences in the Use of Message Cues and Judgments. Journal of Marketing Research 28: 84-96. Milliman, R.E., and D.L. Fugate. 1993. Atmospherics as an emerging influence in the design of exchange environments. Journal of Marketing Management 3: 66-74 Mittal, B. I. 1989. Measuring purchase-decision involvement. Psychology and mark eting 6, no.2 : 147 162. Nunnally, J.C. 1978. Psychometric Theory, 2nd edition, New York: McGraw Hill, Ognianova, E. 1998. Effects of the Content Provider s Perceived Credibility and Id entity on Ad Processing in Computer-Mediated Environments. Paper presented at the America Academy of Advert ising Annual Conference, Lexington, KY.

Putrevu, S. 2001. Exploring the Origins and Information Processing Differences B etween Men and Women: Implications for Advertisers. Academy of Marketing Science Review 2001; no. 10. Available at: http://www.amsreview.org/articles/putrevu10-2001.pdf Rafaeli, A. and M.G. Pratt. 2005. Artifacts and organizations: Beyond mere Symbo lism. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum 34