Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Act 2655

Uploaded by

Maria Linda GavinoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Act 2655

Uploaded by

Maria Linda GavinoCopyright:

Available Formats

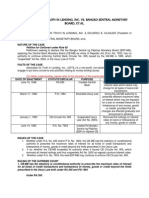

Download 0 Comment Link Embed Readcast 0inShare PALMONES, ELOISA C.

Credit Transactions Usury Law (Act 2655, as amended by Presidential Decree No. 116) The Usury Law is Act 2655, as amended by Presidential Decree No. 116, which provides, among others, that the legal rate of interest for the loan or forbearance of any money, goods or credits, where such loan or renewal or forbearance is secured in whole or in part by a mortgage upon real estate the title to which is duly registered, in the absence of express contract as to such rate of interest, shall be 12% per annum. Any amount of interest paid or stipulated to be paid in excess of that fixed by law is considered usurious, therefore unlawful. However, pursuant to Central Bank Circular No. 905, adopted on 22 December 1982, the Supreme Court declared that the Usury law is now "legally inexistent".It should be clarified that CB Circular No. 905 did not repeal nor in anyway amend the Usury Law but simply suspended the latter's effectivity. Usury has been legally non-existent in our jurisdiction. Interest can now be charged as lender and borrower may agree upon. Usury is defined as: Contracting for or receiving something in excess of the amount allowed by law for the forbearance of money, goods or things in action. Any amount of interest paid or stipulated to be paid in excess of that fixed by law.

Background Taking of excessive interest for the loan of money has been regarded with abhorrence from the earliest times prohibited by the ancient laws of the Chinese and Hindus, the Mosaic Law of the Jews, by the Koran, by the Athenians and by the Romans and has been frowned upon by distinguished publicists throughout all the ages. The early American colonial usury acts were modeled after the English act, the rate of interest allowed being usually higher. These early enactments adopted the penalty for usury fixed by the statue of the mother country. The tendency of subsequent statutes has been steadily to mitigate the punishment inflicted on the usurer. The illegality of usury is now wholly a creature of legislation. The Philippine statute on the subject is Act No. 2655. It is a drastic law following in many respects the most advanced American Legislation. Central Bank Circular No. 905 simply suspended the effectivity of the Usury Law, it did not repeal or in any way suspend the Usury Law. Only a law can repeal another law.

Usury Law

The Usury Law is Act 2655, as amended by Presidential Decree No. 116, which provides, among others, that the legal rate of interest for the loan or forbearance of any money, goods or credits, where such loan or renewal or forbearance is secured in whole or in part by a mortgage upon real estate the title to which is duly registered, in the absence of express contract as to such rate of interest, shall be 12% per annum. Any amount of interest paid or stipulated to be paid in excess of that fixed by law is considered usurious, therefore unlawful. Usury law has been enacted for the protection of the borrower from the imposition of unscrupulous lenders who are ready to take undue advantage of the necessities of others. It forms a part of the public policy of the state, and is intended to prevent excessive charges for the loan of money. It proceeds on the theory that a usurious loan is attributable to such inequality in the relation of the lender and borrower that the borrowers necessities deprive him of freedom in contracting and place him at the mercy of the lender. Pursuant to Central Bank Circular No. 905, adopted on 22 December 1982, the Supreme Court declared that the Usury law is now "legally inexistent". Under the authority.

SECTION 1. The rate of interest, including commissions, premiums, fees and other charges, on a loan or forbearance of any money, goods, or credits, regardless of maturity and whether secured or unsecured, that may be charged or collected by any person, whether natural or juridical, shall not be subject to any ceiling prescribed under or pursuant to the Usury Law, as amended. SECTION 2. The rate of interest for the loan or forbearance of any money, goods or credits and the rate allowed in judgments, in the absence of express contract as to such rate of interest, shall continue to be twelve per cent (12%) per annum. It should be clarified that CB Circular No. 905 did not repeal nor in anyway amend the Usury Law but simply suspended the latter's effectivity. Usury has been legally non-existent in our jurisdiction. Interest can now be charged as lender and borrower may agree upon. Elements: 1. 2. 3. 4. Loan or forbearance. An understanding between the parties that the loan shall or may be returned. Unlawful intent to take more than the legal rate for the use of money. Taking or agreeing to take for the use of the loan of something in excess of what is allowed by law.

To determine whether all of these elements is present, the court will disregard the form which the transaction may take and look only upon its substance. Interest Rates under the Usury Law: With the suspension of the Usury Law and the removal of interest ceilings, the parties are generally free to stipulate the interest rates to be imposed on monetary obligations. As a rule, the interest rate agreed by the creditor and the debtor is binding upon them. This rule, however, is not absolute. The striking down of unconscionable interest is based on Article 1409 of the Civil Code, which considers certain contracts as inexistent and void from the beginning, including: "Those whose cause, object or purpose is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy". In a recent case, the SC again dealt with the validity of interest agreed by the parties, stating that: Stipulated interest rates are illegal if they are unconscionable and the Court is allowed to temper interest rates when necessary. In exercising this vested power to determine what is iniquitous and

unconscionable, the Court must consider the circumstances of each case. What may be iniquitous and unconscionable in one case, may be just in another. In that case, the SC reduced the interest rate from 18% to 12% per annum, noting, among others, that the amount involved has ballooned to an outrageous amount four times the principal debt. Indeed, there is no hard and fast rule to determine the reasonableness of interest rates. Stipulated interest rates of 21%, 23% and 24% per annum had been sustained in certain cases. On the other hand, there are plenty of cases when the SC equitably reduced the stipulated interest rates; for instance, from 18% to 10% per annum. The SC also voided the stipulated interest of 5.5% per month (or 66% per annum), for being excessive, iniquitous, unconscionable and exorbitant, hence, contrary to morals (contra bonos mores), if not against the law. The same is true with cases involving 36% per annum, 6% per month (or 72% per annum), and 10% and 8% per month. In these instances, the SC imposed the legal interest of 12%. legal interest doesnt mean that anything beyond 12% is illegal. It simply means that in a loan or forbearance of money, the interest due should be that stipulated in writing, and in the absence thereof, the rate shall be 12% per annum.

Interest Rate Ceiling The Usury Law had been rendered legally ineffective by Resolution No. 224 dated 3 December 1982 of the Monetary Board of the Central Bank, and later by Central Bank Circular No. 905 which took effect on 1 January 1983. These circulars removed the ceiling on interest rates for secured and unsecured loans regardless of maturity. The effect of these circulars is to allow the parties to agree on any interest that may be charged on a loan. The virtual repeal of the Usury Law is within the range of judicial notice which courts are bound to take into account. Although interest rates are no longer subject to a ceiling, the lender still does not have an unbridled license to impose increased interest rates. The lender and the borrower should agree on the imposed rate, and such imposed rate should be in writing. Here, the stipulations on interest rate repricing are valid because (1) the parties mutually agreed on said stipulations; (2) repricing takes effect only upon Solidbanks written notice to Permanent of the new interest rate; and (3) Permanent has the option to prepay its loan if Permanent and Solidbank do not agree on the new interest rate. The phrases irrevocably authorize, at any time and adjustment of the interest rate shall be effective from the date indicated in the written notice sent to us by the bank, or if no date is indicated, from the time the notice was sent, emphasize that Permanent should receive a written notice from Solidbank as a condition for the adjustment of the interest rates. (Solidbank Corporation vs. Permanent Homes, Inc., G.R. No. 171925, July 23, 2010.)

You might also like

- Advocates For Truth Vs Bangko SentralDocument2 pagesAdvocates For Truth Vs Bangko SentralSamuel Terseis100% (4)

- Memorandum To Depositing InstitutionDocument3 pagesMemorandum To Depositing Institutionapi-3744408100% (1)

- No Person Shall Be Imprisoned For Debt or NonDocument5 pagesNo Person Shall Be Imprisoned For Debt or Nonヘンリー フェランキュッロNo ratings yet

- The Usury Law (De Leon)Document9 pagesThe Usury Law (De Leon)Martin EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Asian Cathay Versus Sps. Gravador G.R. No. 186550Document3 pagesAsian Cathay Versus Sps. Gravador G.R. No. 186550Sharmen Dizon GalleneroNo ratings yet

- Cred Trans DoctrinesDocument6 pagesCred Trans DoctrinesAshaselenaNo ratings yet

- Usury LawDocument3 pagesUsury LawCarolyn Clarin-Baterna100% (2)

- Security Bank and Trust Company v. Regional Trial Court of MakatiDocument2 pagesSecurity Bank and Trust Company v. Regional Trial Court of MakatiMarionnie SabadoNo ratings yet

- Credit Transactions - Cuyco Vs Cuyco DigestDocument10 pagesCredit Transactions - Cuyco Vs Cuyco DigestBigs BeguiaNo ratings yet

- PPT - Truth in Lending ActDocument23 pagesPPT - Truth in Lending ActGigiRuizTicar100% (1)

- Credit Transactions Reviewer Draft 1Document15 pagesCredit Transactions Reviewer Draft 1sei1davidNo ratings yet

- Security Bank and Trust Co vs. RTC MakatiDocument3 pagesSecurity Bank and Trust Co vs. RTC Makaticmv mendozaNo ratings yet

- Advocates of Til vs. BSPDocument3 pagesAdvocates of Til vs. BSPIrene RamiloNo ratings yet

- 21 UCPB v. BelusoDocument3 pages21 UCPB v. BelusoNico de la PazNo ratings yet

- De La Paz Vs L & J DevelopmentDocument3 pagesDe La Paz Vs L & J DevelopmentMary Louisse RulonaNo ratings yet

- Credit - Loan DigestDocument13 pagesCredit - Loan DigestAlyssa Fabella ReyesNo ratings yet

- United Coconut Planters Bank, Petitioner, vs. Spouses Samuel and Odette Beluso, RespondentsDocument3 pagesUnited Coconut Planters Bank, Petitioner, vs. Spouses Samuel and Odette Beluso, RespondentsPam RamosNo ratings yet

- Usury LawDocument4 pagesUsury LawRonnel Seran TanNo ratings yet

- Usury LawDocument1 pageUsury LawAlfred Joseph ZuluetaNo ratings yet

- Stipulation of InterestsDocument4 pagesStipulation of Interestsmarge carreonNo ratings yet

- Tavonga Banking Law and PracticeDocument6 pagesTavonga Banking Law and PracticeTavonga Enerst MasweraNo ratings yet

- GrazeDocument2 pagesGrazeGerwine PuguonNo ratings yet

- 12 Advocates For Truth in Lending V Bangko Sentral Monetary BoardDocument23 pages12 Advocates For Truth in Lending V Bangko Sentral Monetary BoardLeyCodes LeyCodesNo ratings yet

- Security Bank and Trust CompanyDocument2 pagesSecurity Bank and Trust CompanyCistron ExonNo ratings yet

- Credit Transaction CasesDocument30 pagesCredit Transaction CasesLei Bataller BautistaNo ratings yet

- Security Bank and Trust Company vs. RTC of Makati Branch 61Document2 pagesSecurity Bank and Trust Company vs. RTC of Makati Branch 61Arianne AstilleroNo ratings yet

- Article 1175 Nikki BasilioooooDocument40 pagesArticle 1175 Nikki BasilioooooDwin AguilarNo ratings yet

- Credit Case Analysis 13 (Basilisco, Jalefaye)Document1 pageCredit Case Analysis 13 (Basilisco, Jalefaye)jalefaye abapoNo ratings yet

- UsuryDocument1 pageUsuryjalefaye abapoNo ratings yet

- Credit Case Abalysis 14 (Basilisco, Jalefaye)Document1 pageCredit Case Abalysis 14 (Basilisco, Jalefaye)jalefaye abapoNo ratings yet

- Usurious TransactionDocument15 pagesUsurious Transactionvincent nifasNo ratings yet

- CREDIT DIGEST DEAN PAGUIRIGAN 8 - 22 and 24 Not 23Document29 pagesCREDIT DIGEST DEAN PAGUIRIGAN 8 - 22 and 24 Not 23Jovi BigasNo ratings yet

- Equitable CaseDocument2 pagesEquitable CaseLe Obm SizzlingNo ratings yet

- Security Bank and Trust CoDocument2 pagesSecurity Bank and Trust CoTin AngusNo ratings yet

- Credit Transaction AssignmentDocument2 pagesCredit Transaction AssignmentRocky YapNo ratings yet

- Case 2. United Alloy Philippines Corporation vs. UCPB. G.R. No. 175949, January 30, 2017.Document3 pagesCase 2. United Alloy Philippines Corporation vs. UCPB. G.R. No. 175949, January 30, 2017.eUG SACLONo ratings yet

- New SampaguitaDocument54 pagesNew Sampaguitania coline mendozaNo ratings yet

- Advocates For Truth in Lending Act. Vs Bank SentralDocument13 pagesAdvocates For Truth in Lending Act. Vs Bank SentralaudreyracelaNo ratings yet

- Credit Cases - RecitDocument28 pagesCredit Cases - RecitROSASENIA “ROSASENIA, Sweet Angela” Sweet AngelaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Reports Annotated Volume 435Document57 pagesSupreme Court Reports Annotated Volume 435Janice LivingstoneNo ratings yet

- Security Bank vs. RTC of MakatiDocument3 pagesSecurity Bank vs. RTC of MakatiMark TeaNo ratings yet

- Credit Transactions DoctinesDocument18 pagesCredit Transactions Doctinesmanol_salaNo ratings yet

- 6 UCPB v. BelusoDocument51 pages6 UCPB v. BelusoGia DimayugaNo ratings yet

- Almeda v. CADocument14 pagesAlmeda v. CAHilleary VillenaNo ratings yet

- People Vs Venancio ConcepcionDocument8 pagesPeople Vs Venancio ConcepcionJake ObilloNo ratings yet

- Issue: Whether The Legal Interest Rate For A Judgment Involving Damages To Property Is 12%Document2 pagesIssue: Whether The Legal Interest Rate For A Judgment Involving Damages To Property Is 12%Vance CeballosNo ratings yet

- ARTICLE 1306 - Limitations On Contractual Stipulations Under POLICE POWERDocument6 pagesARTICLE 1306 - Limitations On Contractual Stipulations Under POLICE POWERFrances Tracy Carlos Pasicolan100% (1)

- 10 UCPB v. Samuel and BelusoDocument48 pages10 UCPB v. Samuel and BelusoClarice SaguilNo ratings yet

- Credit Transactions Msu College of Law Mutuum: Atty. Norossana Alauya-Sani, CpaDocument9 pagesCredit Transactions Msu College of Law Mutuum: Atty. Norossana Alauya-Sani, CpaOmie Jehan Hadji-AzisNo ratings yet

- 8 Security Bank and Trust Co. vs. RTC of ManilaDocument5 pages8 Security Bank and Trust Co. vs. RTC of Manilarho wanalNo ratings yet

- Case Digests - CreditTransDocument14 pagesCase Digests - CreditTransMaria Fiona Duran MerquitaNo ratings yet

- 54 First Metro Investment V Este Del SolDocument15 pages54 First Metro Investment V Este Del Soljuan aldabaNo ratings yet

- Spec Com CasesDocument12 pagesSpec Com CasesRexan E VillaverNo ratings yet

- Truth in Lending ActDocument7 pagesTruth in Lending ActBea GarciaNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Mutuum Legal Provisions and CasesDocument129 pagesThe Concept of Mutuum Legal Provisions and CasesGerard TinampayNo ratings yet

- GUEVARRA, Robert Arvin G - Loan and DepositDocument3 pagesGUEVARRA, Robert Arvin G - Loan and DepositArvin GuevarraNo ratings yet

- Bacolor Vs Banco FilipinoDocument5 pagesBacolor Vs Banco FilipinoRhodel EllaNo ratings yet

- Presidential Decree No. 1684 - Amending Further Act Numbered Two Thousand Six Hundred Fifty-Five, As Amended, Otherwise Known As "The Usury Law"Document2 pagesPresidential Decree No. 1684 - Amending Further Act Numbered Two Thousand Six Hundred Fifty-Five, As Amended, Otherwise Known As "The Usury Law"Maria Linda GavinoNo ratings yet

- What Is Adm LawDocument3 pagesWhat Is Adm LawMaria Linda GavinoNo ratings yet

- Act 2655Document3 pagesAct 2655Maria Linda GavinoNo ratings yet

- Outline-Transpo and Public Utility LawDocument12 pagesOutline-Transpo and Public Utility LawGretchen MondragonNo ratings yet

- Transpo-Us Vs Tan PiacoDocument10 pagesTranspo-Us Vs Tan PiacoMaria Linda GavinoNo ratings yet