Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dept. of Information and Computer Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Okayama University of Science, 1-1 Ridai-Cho, Okayama 700-0005, Japan

Dept. of Information and Computer Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Okayama University of Science, 1-1 Ridai-Cho, Okayama 700-0005, Japan

Uploaded by

omaneramziOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dept. of Information and Computer Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Okayama University of Science, 1-1 Ridai-Cho, Okayama 700-0005, Japan

Dept. of Information and Computer Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Okayama University of Science, 1-1 Ridai-Cho, Okayama 700-0005, Japan

Uploaded by

omaneramziCopyright:

Available Formats

Defining English for Specific Purposes and the Role of the ESP Practitioner Laurence Anthony Dept.

of Information and Computer Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Okayama University of Science, 1-1 Ridai-cho, Okayama 700-0005, Japan Abstract This paper first defines the 'English for Specific Purposes' (ESP) approach to language teaching in terms of absolute and variable characteristics offered by Dudley-Evans in the plenary speech of the first Japan Conference on English for Specific Purposes. Then, under the headings of teacher, collaborator, course designer and materials provider, researcher, and evaluator proposed by DudleyEvans, a comparison is made between the 'General English' teacher and the so-called ESP practitioner. 1. Growth of ESP

From the early 1960's, English for Specific Purposes (ESP) has grown to become one of the most prominent areas of EFL teaching today. Its development is reflected in the increasing number of universities offering an MA in ESP (e.g. The University of Birmingham, and Aston University in the UK) and in the number of ESP courses offered for overseas students in English speaking countries. There is now a well-established international journal dedicated to ESP discussion, "English for Specific Purposes: An international journal", and the ESP SIG groups of the IATEFL and TESOL are active at their national conferences. In Japan too, the ESP movement has shown a slow but definite growth over the past few years. In particular, increased interest has been spurred by the Ministry of Education's decision in 1994 to largely hand over control of university curriculums to the universities themselves. This has led to a rapid growth in English courses aimed at specific disciplines, e.g. 'English for Chemists', in place of the more traditional 'General English' courses. The ESP community in Japan has also become more defined, with the Japan Association of College English Teachers (JACET) ESP SIG set up in 1996 and the Japan Association of Language Teachers (JALT) N-SIG to be formed shortly. Finally, in November 1997, the ESP community came together as a whole at the first Japan Conference on English for Specific Purposes held at Aizu University in Fukushima Prefecture. 2. The ESP approach

As described above, ESP has had a relatively long time to mature and so we would expect the ESP community to have a clear idea about what ESP means. Strangely, however, this does not seem to be the case. In October of 1997, for example, a heated debate took place on the TESP-L e-mail discussion list about whether or not English for Academic Purposes (EAP) could be considered part

of ESP in general. At the Japan Conference on ESP also, clear differences in how people interpreted the meaning of ESP could be seen. Some described ESP as simply being the teaching of English for any purpose that could be specified. Others, however, were more precise describing it as the teaching of English used in academic studies, or the teaching of English for vocational or professional purposes. The main speaker at the Japan Conference on ESP, Tony Dudley-Evans, is very aware of the current confusion amongst the ESP community, and set out in his one hour speech to clarify the meaning of ESP, giving an extended definition in terms of 'absolute' and 'variable' characteristics (see below). Definition of ESP (Dudley-Evans, 1997) Absolute Characteristics 1. ESP is defined to meet specific needs of the learners 2. ESP makes use of underlying methodology and activities of the discipline it serves 3. ESP is centered on the language appropriate to these activities in terms of grammar, lexis, register, study skills, discourse and genre. Variable Characteristics 1. ESP may be related to or designed for specific disciplines 2. ESP may use, in specific teaching situations, a different methodology from that of General English 3. ESP is likely to be designed for adult learners, either at a tertiary level institution or in a professional work situation. It could, however, be for learners at secondary school level 4. ESP is generally designed for intermediate or advanced students. 5. Most ESP courses assume some basic knowledge of the language systems The definition Dudley-Evans offers is clearly influenced by that of Strevens (1988), although he has improved it substantially by removing the absolute characteristic that ESP is "in contrast with 'General English'" (Johns et al., 1991: 298), and has revised and increased the number of variable characteristics. The division of ESP into absolute and variable characteristics, in particular, is very helpful in resolving arguments about what is and is not ESP. From the definition, we can see that ESP can but is not necessarily concerned with a specific discipline, nor does it have to be aimed at a certain age group or ability range. ESP should be seen simple as an 'approach' to teaching, or what Dudley-Evans describes as an 'attitude of mind'. Such a view echoes that of Hutchinson et al. (1987:19) who state, "ESP is an approach to language teaching in which all decisions as to content and method are based on the learner's reason for learning".

3.

The ESP Practitioner

If we agree with the above definition, we begin to see how broad ESP really is. In fact, one may ask 'What is the difference between the ESP and 'General English' approach?' Hutchinson et al. (1987:53) answer this quite simply, "in theory nothing, in practise a great deal". In 1987, of course, the last statement was quite true. At the time, teachers of 'General English' courses, while acknowledging that students had a specific purpose for studying English, would rarely conduct a needs analysis to find out what was necessary to actually achieve it. Teachers nowadays, however, are much more aware of the importance of needs analysis, and published textbooks have improved dramatically allowing the teacher to select materials which closely match the goals of the learner. Perhaps this demonstrates the influence that the ESP approach has had on English teaching in general. Nevertheless, the line between where 'General English' courses stop and ESP courses start has become very vague indeed. Ironically, although many 'General English' teachers can be described as using an ESP approach, basing their syllabi on a learner needs analysis and their own specialist knowledge of using English for real communication, many so-called ESP teachers are using an approach furthest from that described above. Coming from a background unrelated to the discipline in which they are asked to teach, ESP teachers are usually unable to rely on personal experiences when evaluating materials and considering course goals. At the university level in particular, they are also unable to rely on the views of the learners, who tend not to know what English abilities are required by the profession they hope to enter. The result is that many ESP teachers become slaves to the published textbooks available, and worse, when there are no textbooks available for a particular discipline, resolve to teaching from textbooks which may be quite unsuitable. Dudley Evans describes the true ESP teacher or ESP Practitioner (Swales, 1988) as needing to perform five different roles. These are 1) Teacher, 2) Collaborator, 3) Course designer and materials provider, 4) Researcher and 5) Evaluator. The first role as 'teacher' is synonymous with that of the 'General English' teacher. It is in the performing of the other four roles that differences between the two emerge. In order to meet the specific needs of the learners and adopt the methodology and activities of the target discipline, the ESP Practitioner must first work closely with field specialists. One example of the important results that can emerge from such a collaboration is reported by Orr (1995). This collaboration, however, does not have to end at the development stage and can extend as far as teach teaching, a possibility discussed by Johns et al. (1988). When team teaching is not a possibility, the ESP Practitioner must collaborate more closely with the learners, who will generally be more familiar with the specialized content of materials than the teacher him or herself. Both 'General English' teachers and ESP practitioners are often required to design courses and provide materials. One of the main controversies in the field of ESP is how specific those materials should be. Hutchinson et al. (1987:165) support materials that cover a wide range of fields, arguing that the grammatical structures, functions, discourse structures, skills, and strategies of different

disciplines are identical. More recent research, however, has shown this not to be the case. Hansen (1988), for example, describes clear differences between anthropology and sociology texts, and Anthony (1998) shows unique features of writing in the field of engineering. Unfortunately, with the exception of textbooks designed for major fields such as computer science and business studies, most tend to use topics from multiple disciplines, making much of the material redundant and perhaps even confusing the learner as to what is appropriate in the target field. Many ESP practitioners are therefore left with no alternative than to develop original materials. It is here that the ESP practitioner's role as 'researcher' is especially important, with results leading directly to appropriate materials for the classroom. The final role as 'evaluator' is perhaps the role that ESP practitioners have neglected most to date. As Johns et al. (1991) describe, there have been few empirical studies that test the effectiveness of ESP courses. For example, the only evaluation of the non compulsory course reported by Hall et al. (1986:158) is that despite carrying no credits, "students continue to attend despite rival pressures of a heavy programme of credit courses". On the other hand, recent work such as that of Jenkins et al. (1993) suggests an increasing interest in this area of research. 4. Conclusion

If the ESP community hopes to grow, it is vital that the community as a whole understands what ESP actually represents, and can accept the various roles that ESP practitioners need to adopt to ensure its success. Only then, can new members join with confidence, and existing members carry on the practices which have brought ESP to the position that it has in EFL teaching today. In Japan, in particular, ESP is still in its infancy and so now is the ideal time to form such a consensus. 5. References

Anthony, L. (1998). Preaching to Cannibals: A Look at Academic Writing in Engineering. Proceedings of the Japan Conference on English for Specific Purposes (forthcoming). Dudley-Evans, T. (1998). Developments in English for Specific Purposes: A multi-disciplinary approach. Cambridge University Press. Hall, D., Hawkey, R., Kenny B., & Storer G. (1986). Patterns of thought in scientific writing: A course in information structuring for engineering students. English for Specific Purposes, 5:147160. Hansen, K. (1988). Rhetoric and epistemology in the social sciences: A contrast of two representative texts. In D. A. Joliffe (Ed.), Writing in Academic Disciplines: Advances in Writing Research. Norwood. Hutchinson, T. & Waters, A. (1987). English for Specific Purposes: A learner-centered approach. Cambridge University Press. Jenkins, S., Jordan, M. K., & Weiland, P. O. (1993). The role of writing in graduate engineering

education: A survey of faculty beliefs and practices. English for Specific Purposes, 12:51-67. Johns, T. F. & Dudley-Evans, T. (1988). An experiment in team teaching overseas postgraduate students of transportation and plant biology. In J. Swales (Ed.), Episodes in ESP. Prentice Hall. Johns, A. M. & Dudley-Evans, T. (1991). English for Specific Purposes: International in Scope, Specific in Purpose. TESOL Quarterly 25:2, 297-314. Orr, T. (1995). Models of Professional Writing Practices Within the Field of Computer Science. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. Ball State University. Strevens, P. (1988). ESP after twenty years: A re-appraisal. In M. Tickoo (Ed.), ESP: State of the art (1-13). SEAMEO Regional Language Centre. Swales, J. (1988). Episodes in ESP. Prentice Hall.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (347)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Frankho Ba Gua Mathematics (Chinese Eight Diagrams Mathematics)Document18 pagesFrankho Ba Gua Mathematics (Chinese Eight Diagrams Mathematics)Frank HoNo ratings yet

- Educational PerennialismDocument3 pagesEducational Perennialisminkhaven09No ratings yet

- Teach Primary 01 2020 01 02 PDFDocument130 pagesTeach Primary 01 2020 01 02 PDFRenee RavalNo ratings yet

- Psychodrama: Chapter 8: Theory & Practice of Group Counseling. Gerald CoreyDocument18 pagesPsychodrama: Chapter 8: Theory & Practice of Group Counseling. Gerald Coreyfelicia_enache_1100% (1)

- Sprigboard Unit 1Document84 pagesSprigboard Unit 1api-30192479No ratings yet

- Emt410 Asessment 1 UploadDocument32 pagesEmt410 Asessment 1 Uploadapi-354631612No ratings yet

- Cover VocabularyDocument1 pageCover VocabularyImam Syafi'iNo ratings yet

- Speaking Group ScheduleDocument1 pageSpeaking Group ScheduleImam Syafi'iNo ratings yet

- (Speech) Go GreenDocument2 pages(Speech) Go GreenImam Syafi'i67% (3)

- The Accelerated English Course and Training Alifia InstituteDocument4 pagesThe Accelerated English Course and Training Alifia InstituteImam Syafi'iNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan: NO Activities DurationDocument1 pageLesson Plan: NO Activities DurationImam Syafi'iNo ratings yet

- Wheaton, Team. Style, Diction, Tone, and Voice, Wheaton College Writing Center: Illinois, 2009Document4 pagesWheaton, Team. Style, Diction, Tone, and Voice, Wheaton College Writing Center: Illinois, 2009Imam Syafi'iNo ratings yet

- Questions PracticeDocument2 pagesQuestions PracticeImam Syafi'iNo ratings yet

- Schedule and Tutor's InformationsDocument1 pageSchedule and Tutor's InformationsImam Syafi'iNo ratings yet

- Parts of Speech, Phrase and ClauseDocument16 pagesParts of Speech, Phrase and ClauseImam Syafi'iNo ratings yet

- Class: - Period: - Date: - Class: - Period: - DateDocument1 pageClass: - Period: - Date: - Class: - Period: - DateImam Syafi'iNo ratings yet

- NO Name Meeting Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday I II I II I II IDocument4 pagesNO Name Meeting Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday I II I II I II IImam Syafi'iNo ratings yet

- Run-Down Acara Closing Meeting and Farewell PartyDocument2 pagesRun-Down Acara Closing Meeting and Farewell PartyImam Syafi'iNo ratings yet

- Sweep Plying Went Finished Yard: ScoreDocument1 pageSweep Plying Went Finished Yard: ScoreImam Syafi'iNo ratings yet

- Pre-Test Scoring and Tabulating Class DistributionDocument2 pagesPre-Test Scoring and Tabulating Class DistributionImam Syafi'iNo ratings yet

- MC FormalDocument3 pagesMC FormalImam Syafi'iNo ratings yet

- Impression SpeechDocument1 pageImpression SpeechImam Syafi'iNo ratings yet

- Impression Speech (MTSN Ponorogo, 2015)Document1 pageImpression Speech (MTSN Ponorogo, 2015)Imam Syafi'iNo ratings yet

- Student Power by Aaron KreiderDocument15 pagesStudent Power by Aaron KreiderJohnPaoloBencitoNo ratings yet

- 0620 s12 Ms 62Document4 pages0620 s12 Ms 62Mohamed Al SharkawyNo ratings yet

- 15 Day Penniman ChartDocument6 pages15 Day Penniman Chartapi-502300054No ratings yet

- Scholarship Form UPHDocument2 pagesScholarship Form UPHNathania BenitaNo ratings yet

- Portfolio: Results-Based Performance Management System (RPMS)Document6 pagesPortfolio: Results-Based Performance Management System (RPMS)Estrelita B. SantiagoNo ratings yet

- The Gnat and The Bull 15Document7 pagesThe Gnat and The Bull 15Donnette DavisNo ratings yet

- Literature Review PaperDocument13 pagesLiterature Review Paperapi-644641708No ratings yet

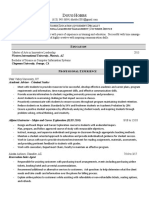

- Doug Hobbs ResumeDocument2 pagesDoug Hobbs Resumeapi-352502361No ratings yet

- The Inter Board Committee of Chairmen (IBCC) Pakistan - Equivalence Form by HubbakDocument4 pagesThe Inter Board Committee of Chairmen (IBCC) Pakistan - Equivalence Form by HubbakHubbak KhanNo ratings yet

- OVC Malawi Communications StrategyDocument28 pagesOVC Malawi Communications StrategyCridoc DocumentationNo ratings yet

- PEGACPDCV171 Certified-Pega-Decisioning-Consultant Exam Blueprint 20160302Document5 pagesPEGACPDCV171 Certified-Pega-Decisioning-Consultant Exam Blueprint 20160302ancella123100% (2)

- Caronan vs. Caronan, A.C. No. 11316, July 12, 2016Document4 pagesCaronan vs. Caronan, A.C. No. 11316, July 12, 2016Edgar Joshua TimbangNo ratings yet

- 2c2ba Practice Test Unit 5Document4 pages2c2ba Practice Test Unit 5lourdesNo ratings yet

- Week 8-9Document19 pagesWeek 8-9Valentina TrianaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Aids: Presenter by Muhammad Rashedul Huq Shamim Associate Professor Department of TVE IUTDocument26 pagesTeaching Aids: Presenter by Muhammad Rashedul Huq Shamim Associate Professor Department of TVE IUTRover Mousum KabirNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Year 2Document34 pagesLesson Plan Year 2rm53100% (1)

- Spanish Project Rubric Verbalfinalexam Jan2014 1Document2 pagesSpanish Project Rubric Verbalfinalexam Jan2014 1api-256368961No ratings yet

- BRAC Final RecommendationsDocument19 pagesBRAC Final Recommendationsslong4No ratings yet

- Conference Program Howard University Updated November 2015Document15 pagesConference Program Howard University Updated November 2015Office on Latino Affairs (OLA)No ratings yet

- Some Things A Scene Might Be - Will StrawDocument10 pagesSome Things A Scene Might Be - Will StrawYoun Liu100% (1)

- DasaDocument2 pagesDasaapi-417427364No ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning Then and Now Picture Description Exercises 103702Document1 pageTeaching and Learning Then and Now Picture Description Exercises 103702Nur Qona AhNo ratings yet

- 4A07 Nguyen Thi Xuan Mai English and Vietnamese ConsonantsDocument18 pages4A07 Nguyen Thi Xuan Mai English and Vietnamese Consonantsnbt411No ratings yet

- New Literacy Skills in The 21st Century ClassroomDocument6 pagesNew Literacy Skills in The 21st Century ClassroomRhynzel Macadaeg BahiwagNo ratings yet