Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter 3 - Elasticity of Demand and Supply

Uploaded by

ohyeajcrocksOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 3 - Elasticity of Demand and Supply

Uploaded by

ohyeajcrocksCopyright:

Available Formats

Written by: Edmund Quek

CHAPTER 3 ELASTICITY OF DEMAND AND SUPPLY

LECTURE OUTLINE 1 2 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 3 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 4 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 5 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 INTRODUCTION PRICE ELASTICITY OF DEMAND Definition and formula of price elasticity of demand Interpreting price elasticity of demand Use of price elasticity of demand Linear downward-sloping demand curve (optional) Determinants of price elasticity of demand INCOME ELASTICITY OF DEMAND Definition and formula of income elasticity of demand Interpreting income elasticity of demand Use of income elasticity of demand Determinants of income elasticity of demand CROSS ELASTICITY OF DEMAND Definition and formula of cross elasticity of demand Interpreting cross elasticity of demand Use of cross elasticity of demand Determinants of cross elasticity of demand PRICE ELASTICITY OF SUPPLY Definition and formula of price elasticity of supply Interpreting price elasticity of supply Linear upward-sloping supply curve (optional) Determinants of price elasticity of supply

6 LIMITATIONS OF THE CONCEPTS OF ELASTICITY OF DEMAND References John Sloman, Economics William A. McEachern, Economics Richard G. Lipsey and K. Alec Chrystal, Positive Economics G. F. Stanlake and Susan Grant, Introductory Economics Michael Parkin, Economics David Begg, Stanley Fischer and Rudiger Dornbusch, Economics

2011 Economics Cafe All rights reserved.

Page 1

Written by: Edmund Quek

INTRODUCTION

We have learnt that a fall in price will lead to a rise in quantity demanded and vice versa. However, given any change in price, in addition to the direction of the change in quantity demanded, economists are also interested to find the magnitude of the change. To measure this, economists use the concept of price elasticity of demand. This chapter gives an exposition of the concepts of price elasticity of demand, income elasticity of demand, cross elasticity of demand and price elasticity of supply.

2 2.1

PRICE ELASTICITY OF DEMAND Definition and formula of price elasticity of demand

Definition The price elasticity of demand (PED) for a good is a measure of the degree of responsiveness of the quantity demanded to a change in the price, ceteris paribus. Formula % Quantity Demanded PED ------------------------------% Price

2.2

Interpreting price elasticity of demand

Due to the law of demand, the PED for a good is always negative. However, the common practice among economists is to omit the negative sign. If the PED for a good is greater than one, the demand is price elastic which means that a change in the price will lead to a larger percentage change in the quantity demanded. A good with an elastic demand has a relatively flat demand curve. If the PED for a good is less than one, the demand is price inelastic which means that a change in the price will lead to a smaller percentage change in the quantity demanded. A good with an inelastic demand has a relatively steep demand curve. If the PED for a good is equal to one, the demand is unit price elastic which means that a change in the price will lead to the same percentage change in the quantity demanded. The demand curve for a good with a unit elastic demand is a rectangular hyperbola.

2011 Economics Cafe All rights reserved.

Page 2

Written by: Edmund Quek

If the PED for a good is zero, the demand is perfectly price inelastic which means that a change in the price will not lead to any change in the quantity demanded. A good with a perfectly inelastic demand has a vertical demand curve. If the PED for a good is infinity, the demand is perfectly price elastic which means that a rise (not a fall) in the price will lead to an infinite decrease in the quantity demanded. A good with a perfectly elastic demand has a horizontal demand curve.

2.3

Use of price elasticity of demand

If the demand for the good produced by a firm is price elastic, the firm can decrease price to increase total revenue as the quantity demanded will increase by a larger percentage.

In the above diagram, area A represents the gain in revenue resulting from the increase in the quantity demanded (Q) and area B represents the loss in revenue resulting from the decrease in the price (P). Since the gain exceeds the loss, total revenue rises. If the demand for the good produced by a firm is price inelastic, the firm can increase price to increase total revenue as the quantity demanded will decrease by a smaller percentage.

2011 Economics Cafe All rights reserved.

Page 3

Written by: Edmund Quek

In the above diagram, area C represents the gain in revenue resulting from the increase in the price (P) and area D represents the loss in revenue resulting from the decrease in the quantity demanded (Q). Since the gain exceeds the loss, total revenue rises. If the demand for the good produced by a firm is unit price elastic, the firm cannot change price to increase total revenue as the quantity demanded will change by the same percentage. 2.4 Linear downward-sloping demand curve (optional)

Along a linear downward-sloping demand curve, PED is different at different points along the demand curve. As we move down along a linear downward-sloping demand curve, PED falls from infinity to zero. If the demand curve is linear, the total revenue curve will be Hill-shaped. Example Price 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

Quantity demanded 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

Total revenue 0 5 8 9 8 5 0

Average revenue 5 4 3 2 1 0

Marginal revenue 5 3 1 -1 -3 -5

PED 5 2 1 0.5 0.2 0

Total revenue (TR) Price (P) x Quantity (Q) Average revenue (AR) TR/Q P ( Demand curve AR curve) Marginal revenue (MR) TR/Q

2011 Economics Cafe All rights reserved.

Page 4

Written by: Edmund Quek

In the above table, as quantity rises, TR rises from zero to nine and then falls back to zero. MR is the additional revenue resulting from selling one more unit of a good. TR is maximised where PED is 1 since any change in price will lead to the same percentage change in quantity demanded. If we assume that quantity is continuously divisible, this will happen where MR is equal to zero. TR curve and MR curve that correspond to a linear downward-sloping demand curve

Note: MR is lower than AR because if the firm wants to sell one more unit of the good, not only must it lower the price of the unit, but it must also lower the price of all the previous units. With the use of differential calculus, we can show that the slope of the MR curve is twice that of the AR curve. When economists speak of elastic demand, what they mean is that PED is greater than one at all the points along the demand curve and a necessary condition for this to happen is that the demand curve is not linear.

2011 Economics Cafe All rights reserved.

Page 5

Written by: Edmund Quek

2.5

Determinants of price elasticity of demand

Number of substitutes The larger the number of substitutes for a good, the higher the PED for the good. Conversely, the smaller the number of substitutes for a good, the lower the PED for the good. The number of substitutes for a good depends, in part, on how narrowly, and for that matter, how broadly the good is defined. The more narrowly a good is defined (e.g. carrots, cabbages), the more elastic the demand for the good. Conversely, the more broadly a good is defined (e.g. vegetables or even food), the less elastic the demand for the good. Closeness of substitutes The closer the substitutes for a good, the higher the PED for the good. Conversely, the farther the substitutes for a good, the lower the PED for the good. Degree of necessity The higher the degree of necessity of a good, the lower the PED for the good. Conversely, the lower the degree of necessity of a good, the higher the PED for the good. Proportion of income spent on the good The larger the proportion of income spent on the good, the higher the PED for the good. Conversely, the smaller the proportion of income spent on a good, the lower the PED for the good. Time period The longer the time period after a change in the price of a good, the higher the PED for the good.

3 3.1

INCOME ELASTICITY OF DEMAND Definition and formula of income elasticity of demand

Definition The income elasticity of demand (YED) for a good is a measure of the degree of responsiveness of the quantity demanded to a change in income, ceteris paribus. Formula % Quantity Demanded YED -------------------------------% Income

2011 Economics Cafe All rights reserved.

Page 6

Written by: Edmund Quek

3.2

Interpreting income elasticity of demand

If the YED for a good is positive, the good is a normal good. A normal good is a good whose demand rises when consumers income rises. There are two types of normal good: necessity and luxury. If the YED for a good is positive but less than one, the good is a necessity. In other words, the demand for a necessity is income inelastic. If the YED for a good is greater than one, the good is a luxury. In other words, the demand for a luxury is income elastic. If the YED for a good is negative, the good is an inferior good. An inferior good is a good whose demand falls when consumers income rises. The concepts of normal and inferior goods can be depicted by an Engels curve. The Engels curve of a good shows the quantity of the good demanded at each income level. The Engels curve

In the above diagram, the good is normal between income levels Y0 and Y1 and inferior between income levels Y1 and Y2. 3.3 Use of income elasticity of demand

The concept of YED allows a firm to determine the future size of the market for its good and hence its production capacity. Suppose that the YED for a good is positive. If a firm that produces the good predicts an economic boom, it can consider increasing its production capacity to meet the increase in demand if the boom arrives. Conversely, if the firm predicts a recession, it can consider decreasing its production capacity or holding back any expansion plan to minimise excess production capacity if the recession arrives.

2011 Economics Cafe All rights reserved.

Page 7

Written by: Edmund Quek

3.4

Determinants of income elasticity of demand

The YED for a good will be lower the higher the level of income and wealth of consumers.

4 4.1

CROSS ELASTICITY OF DEMAND Definition and formula of cross elasticity of demand

Definition The cross elasticity of demand (XED) for a good with respect to another good is a measure of the degree of responsiveness of the quantity of the first good demanded to a change in the price of the second good, ceteris paribus. Let the two goods be good A and good B. Formula % Quantity Demanded of Good A XEDAB = ----------------------------------------------% Price of Good B

4.2

Interpreting cross elasticity of demand

If the XEDAB is positive, good A and good B are substitutes, which means that the two goods are alternatives to each other.

In the above diagram, the demand curve (DAB) relating the quantity demanded of good A to the price of good B is upward-sloping. If the price of good B rises, consumers will buy less of it. Since good A and good B are substitutes, they will buy more good A.

2011 Economics Cafe All rights reserved.

Page 8

Written by: Edmund Quek

If the XEDAB is negative, good A and good B are complements, which means that the two goods are consumed together.

In the above diagram, the demand curve (DAB) relating the quantity demanded of good A to the price of good B is downward-sloping. If the price of good B rises, consumers will buy less of it. Since good A and good B are complements, they will buy less good A.

4.3

Use of cross elasticity of demand

The concept of XED allows a firm to determine how a change in the price of a related good produced by another firm will affect the demand for its good. For instance, if a firm that produces a substitute decreases its price, the firm will also need to decrease its price to avoid suffering a decrease in demand and this is due to the positive XED between substitutes. However, it should take into consideration the possibility of a price war. If a firm that produces a substitute increases its price, the firm can increase total revenue by keeping its price unchanged. However, if does not have excess production capacity, it may need to increase its price to increase total revenue. If a firm produces more than one good, lets say two goods, the concept of XED also allows the firm to determine how the demand for one good will be affected if it changes the price of the other good.

4.4

Determinants of cross elasticity of demand

The XED between two goods will be higher the more closely they are related. Hence, a large positive XED indicates very close substitutes and a large negative XED indicates very close complements.

2011 Economics Cafe All rights reserved.

Page 9

Written by: Edmund Quek

5 5.1

PRICE ELASTICITY OF SUPPLY Definition and formula of price elasticity of supply

Definition The price elasticity of supply (PES) of a good is a measure of the degree of responsiveness of the quantity of the good supplied to a change in the price, ceteris paribus. Formula % Quantity Supplied PES -----------------------------% Price

5.2

Interpreting price elasticity of supply

Due to the law of supply, the PES of a good is always positive. If the PES of a good is greater than one, the supply of the good is price elastic which means that a change in the price of the good will lead to a larger percentage change in the quantity supplied. A good with an elastic supply has a relatively flat supply curve. If the PES of a good is less than one, the supply of the good is price inelastic which means that a change in the price of the good will lead to a smaller percentage change in the quantity supplied. A good with an inelastic supply has a relatively steep supply curve. If the PES of a good is equal to one, the supply of the good is unit price elastic which means that a change in the price of the good will lead to the same percentage change in the quantity supplied. If the PES of a good is zero, the supply of the good is perfectly price inelastic which means that a change in the price of the good will not lead to any change in the quantity supplied. A good with a perfectly inelastic supply has a vertical supply curve. If the PES of a good is infinity, the supply of the good is perfectly price elastic which means that a fall (not a rise) in the price of the good will lead to an infinite decrease in the quantity supplied. A good with a perfectly elastic supply has a horizontal supply curve.

5.3

Linear upward-sloping supply curve (optional)

Along a linear upward-sloping supply curve, PES is different at different points along the supply curve, unless the supply curve intersects the origin as a linear upward-sloping

2011 Economics Cafe All rights reserved.

Page 10

Written by: Edmund Quek

supply curve which intersects the origin has a unit price elasticity of supply at all points along the supply curve, regardless of the slope. A linear upward-sloping supply curve which intersects the price-axis has a PES greater than one at all points along the supply curve, regardless of the slope. Although all the points along such a supply curve has a PES greater than one, the value of PES decreases as we move up along the supply curve. A linear upward-sloping supply curve which intersects the quantity-axis has a PES less than one at all points along the supply curve, regardless of the slope. Although all the points along such a supply curve has a PES less than one, the value of PES increases as we move up along the supply curve.

5.4

Determinants of price elasticity of supply

Definition of the good The PES of a good is higher the more narrowly the good is defined. For instance, the PES of a crop is higher than the PES of crops as a whole as it is easier to obtain factor inputs to produce a crop within the agricultural sector than from other industries. Time period The longer the time period after an increase in the price of a good, the higher the PES of the good as firms are able to increase output by a larger amount with more time. Time period can be divided into the immediate run, the short run and the long run. The immediate run is the time period that is so short that output is fixed. The supply curve of the good is perfectly inelastic, assuming firms do not keep stocks of the good. The short run is the time period during which at least one of the factor inputs used in the production process is fixed. In the short run, when the price of a good rises, firms can increase output only by employing more of the variable factor inputs used in the production process. The long run is the time period after which all the factor inputs used in the production process are variable. The PES of a good in the long run is higher than the PES in the short run as firms can increase output by employing more of all the factor inputs used in the production process and potential firms can enter the industry in the long run. Nature of the good The supply of a non-perishable good is normally more price elastic than the supply of a perishable good. If a good is non-perishable, such as a manufactured good, firms can keep stocks of the good. Therefore, if the price rises, firms can increase the quantity supplied by increasing output and by running down their stocks. However, if a good is perishable, such as an agricultural product, firms cannot keep stocks of the good. Therefore, if the price rises, firms can only increase the quantity supplied by increasing output. Further, the growing time of a perishable good is normally longer than the production time of a non-perishable good.

2011 Economics Cafe All rights reserved.

Page 11

Written by: Edmund Quek

Behaviour of marginal cost as firms change output Given a change in price of a good, the lower the output level and hence capacity utilisation, the less rapidly marginal cost will change as firms change output. The less rapidly marginal cost will change as firms change output, the larger the change in output. Therefore, the lower the output level of a good, the higher the PES of the good. Mobility of factor inputs The ease with which factor inputs can move from the production of one good to another will influence PES. The higher the mobility of factor inputs, the higher the PES of a good. The mobility of factor inputs depends to some extent on the time period.

LIMITATIONS OF THE CONCEPTS OF ELASTICITY OF DEMAND

The concepts of elasticity of demand are subject to several limitations. First, data from past records may no longer be relevant to calculating elasticities of demand as some of the determinants of demand may have changed. Second, although data from current surveys are relevant to calculating elasticities of demand, they may not be reliable because the respondents may not be truthful in their answers. Further, if the sample size of the surveys is small, the results may not be reflective of the actual market for the good. Having a larger sample size will result in a higher cost. Third, the assumption of ceteris paribus that is made in calculating elasticities of demand is unlikely to hold in reality.

Note: More advanced applications of the concepts of elasticity of demand will be discussed in the essays. In addition, students must also know the usefulness of the concepts of elasticity of demand to the government which will also be discussed in the essays.

2011 Economics Cafe All rights reserved.

Page 12

You might also like

- Elasticity of DemandDocument38 pagesElasticity of DemandimadNo ratings yet

- Elasticity Is A Measure of ResponsivenessDocument7 pagesElasticity Is A Measure of ResponsivenessAlesiaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 Market StructuresDocument33 pagesChapter 7 Market StructuresAtikah RawiNo ratings yet

- Income & Substitution EffectDocument4 pagesIncome & Substitution EffectRishabh HajelaNo ratings yet

- Chap 04Document16 pagesChap 04Syed Hamdan100% (1)

- Managerial EconomicsDocument10 pagesManagerial EconomicsDipali DeoreNo ratings yet

- Chap 05Document53 pagesChap 05Tâm TrầnNo ratings yet

- Elasticity and InelasticityDocument2 pagesElasticity and InelasticityKarl BrattNo ratings yet

- Law of Supply and DemandDocument6 pagesLaw of Supply and DemandArchill YapparconNo ratings yet

- Group Cat - Gen 005Document19 pagesGroup Cat - Gen 005Mike Angelo Gare PitoNo ratings yet

- Essay On PovertyDocument4 pagesEssay On PovertyDaman-e-zehraNo ratings yet

- Problem Set 3Document5 pagesProblem Set 3Nguyễn Vũ ThanhNo ratings yet

- 10 Principles of Economics - WikiversityDocument24 pages10 Principles of Economics - WikiversityprudenceNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Elasticity and Its ApplicationDocument41 pagesChapter 5 Elasticity and Its ApplicationeiaNo ratings yet

- ECON 201 Practice Test 2 (Chapter 5, 6 and 21)Document9 pagesECON 201 Practice Test 2 (Chapter 5, 6 and 21)Meghna N MenonNo ratings yet

- Basic Analysis of Demand and Supply 1Document6 pagesBasic Analysis of Demand and Supply 1Jasmine GarciaNo ratings yet

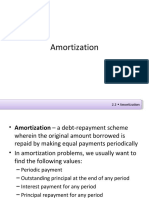

- AmortizationDocument41 pagesAmortizationrichmond buquingNo ratings yet

- KAREN LUZON - Dirty Money - Reaction PaperDocument1 pageKAREN LUZON - Dirty Money - Reaction PaperJane BermoyNo ratings yet

- Original Chapter 4 Consumer Choice and DemandDocument12 pagesOriginal Chapter 4 Consumer Choice and DemandJohn Darrelle de LeonNo ratings yet

- Analyze Demand and Supply PrinciplesDocument33 pagesAnalyze Demand and Supply Principlesgeraldine andalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - Theory of ConsumptionDocument13 pagesChapter 4 - Theory of ConsumptionWingmannuuNo ratings yet

- 3.1. Elasticity and Its ApplicationDocument26 pages3.1. Elasticity and Its ApplicationSamantha Cinco100% (2)

- Theory of Consumer BehaviorDocument32 pagesTheory of Consumer Behaviorkiesha pastranaNo ratings yet

- Law of Supply and DemandDocument4 pagesLaw of Supply and DemandSteven MoisesNo ratings yet

- Chapter FourDocument35 pagesChapter FourshimelisNo ratings yet

- In Defence of What Must Be Said by G. GrassDocument5 pagesIn Defence of What Must Be Said by G. GrasskristijankrkacNo ratings yet

- Factors of Production LessonDocument10 pagesFactors of Production LessonPennyNo ratings yet

- Price ElasticityDocument2 pagesPrice ElasticityKinNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7: Production and Cost in The FirmDocument3 pagesChapter 7: Production and Cost in The FirmemilianodelgadoNo ratings yet

- Financial Environment Chapter 1 SummaryDocument57 pagesFinancial Environment Chapter 1 Summaryn nNo ratings yet

- DemandDocument22 pagesDemandSerenity KerrNo ratings yet

- BAC 101 Course Module Week 2Document35 pagesBAC 101 Course Module Week 2Messy S. BegontesNo ratings yet

- Four Phases of the Business Cycle ExplainedDocument5 pagesFour Phases of the Business Cycle ExplainedSonia LawsonNo ratings yet

- Elasticity and Consumer BehaviorDocument7 pagesElasticity and Consumer BehaviorMhel Demabogte100% (1)

- Informative Speech: Smart VotersDocument2 pagesInformative Speech: Smart VotersPrinces Macale BoritoNo ratings yet

- Describe The Basic Premise of Adam SmithDocument8 pagesDescribe The Basic Premise of Adam SmithJm B. VillarNo ratings yet

- Welfare EconomicsDocument6 pagesWelfare EconomicsVincent CariñoNo ratings yet

- Econ 1 PS2 KeyDocument4 pagesEcon 1 PS2 KeyDavid LamNo ratings yet

- Accounting For Purchases and Sale of MerchandiseDocument4 pagesAccounting For Purchases and Sale of MerchandiseRaissa MaeNo ratings yet

- Art. 1156 - An Obligation Is A: Juridical Necessity To Give, To Do or Not To DoDocument46 pagesArt. 1156 - An Obligation Is A: Juridical Necessity To Give, To Do or Not To DoBenchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Final Exam ReviewDocument19 pagesFinal Exam ReviewJeromy Rech100% (1)

- Instructional Materials For Microeconomics: Polytechnic University of The PhilippinesDocument10 pagesInstructional Materials For Microeconomics: Polytechnic University of The PhilippinesIan Jowmariell GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Elasticity of Demand and SupplyDocument18 pagesElasticity of Demand and SupplyMochimNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Elasticity Test and AnswerDocument13 pagesChapter 4 Elasticity Test and AnswerWendors Wendors100% (3)

- ECON01G - Lec4 - Elasticity of Demand and SupplyDocument4 pagesECON01G - Lec4 - Elasticity of Demand and Supplyami100% (1)

- Marshall McLuhan's Theory of Communication AgesDocument8 pagesMarshall McLuhan's Theory of Communication AgesLarsen PerezNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 The Theory of Individual BehaviorDocument51 pagesChapter 4 The Theory of Individual BehaviorAyelle AdeNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region III Schools Division of Pampanga Pre-Test English For Academic and Professional PurposesDocument7 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Department of Education Region III Schools Division of Pampanga Pre-Test English For Academic and Professional PurposesKyla Nadine AnusencionNo ratings yet

- 7 Pricing DecisionsDocument14 pages7 Pricing DecisionsZenCamandangNo ratings yet

- Module 1 The Study of EconomicsDocument101 pagesModule 1 The Study of EconomicsEdrei Anthony RoblesNo ratings yet

- Chap 05Document16 pagesChap 05Syed Hamdan0% (2)

- RPH Course OutlineDocument5 pagesRPH Course OutlineDahlia Galimba100% (1)

- BBA 1st Semester SyllabusDocument12 pagesBBA 1st Semester SyllabusBinay Tiwary80% (5)

- Chapter 1Document19 pagesChapter 1Krissa Mae LongosNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5Document8 pagesChapter 5K57 TRAN THI MINH NGOCNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document5 pagesChapter 2Sundaramani SaranNo ratings yet

- Solved Problems of McconellDocument64 pagesSolved Problems of McconellAhsan Jalal0% (1)

- Ayaz Nujuraully - 59376351 1Document12 pagesAyaz Nujuraully - 59376351 1AzharNo ratings yet

- Determining Composition of Gas Canister Using Combustion AnalysisDocument15 pagesDetermining Composition of Gas Canister Using Combustion AnalysisLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- Science PSLE PreparationsDocument45 pagesScience PSLE PreparationsRaghu Pavithara100% (1)

- Java Samples P6 Maths Prelims 2013 Methodist GirlsDocument34 pagesJava Samples P6 Maths Prelims 2013 Methodist GirlsLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- Minfong Ho WorksheetDocument3 pagesMinfong Ho WorksheetLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- PSLE Situational Writing PreparationDocument13 pagesPSLE Situational Writing PreparationLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- The Thai Village - Appreciating Story SettingDocument4 pagesThe Thai Village - Appreciating Story SettingLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- Java Samples P6 Maths Prelims 2013 Raffles GirlsDocument36 pagesJava Samples P6 Maths Prelims 2013 Raffles GirlsLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- Science PSLE PreparationsDocument45 pagesScience PSLE PreparationsRaghu Pavithara100% (1)

- PSLE Composition Preparation - 2009Document50 pagesPSLE Composition Preparation - 2009Zainuddin Abdul Karim100% (2)

- Java Samples P6 Maths Prelims 2013 Nan HuaDocument40 pagesJava Samples P6 Maths Prelims 2013 Nan HuaLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- Miniature Word Pictures To Capture The ImaginationDocument5 pagesMiniature Word Pictures To Capture The ImaginationLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- P6 Maths 2014 CA1 Methodist GirlsDocument36 pagesP6 Maths 2014 CA1 Methodist GirlsLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- Home-Based Lesson Plans For Year 1 (ELA)Document8 pagesHome-Based Lesson Plans For Year 1 (ELA)Liling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- Minfong HoDocument8 pagesMinfong HoLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- Learning: Resource Section of Our Site Joshua Foer's 'Moonwalking With Einstein'Document3 pagesLearning: Resource Section of Our Site Joshua Foer's 'Moonwalking With Einstein'Liling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- Crafts Ebook Kirigami Paper Japanese - Arts of Paper - OrigamiDocument59 pagesCrafts Ebook Kirigami Paper Japanese - Arts of Paper - Origamisusiblue63% (8)

- 5 PythThm Linear IneqDocument1 page5 PythThm Linear IneqLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- After Twenty YearsDocument1 pageAfter Twenty YearsLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- June Holiday AssignmentDocument5 pagesJune Holiday AssignmentLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- June Holiday AssignmentDocument5 pagesJune Holiday AssignmentLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 The Theory of Production PDFDocument9 pagesChapter 5 The Theory of Production PDFLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- Composition Writing SkillsDocument6 pagesComposition Writing SkillsLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Demand and SupplyDocument17 pagesChapter 2 Demand and SupplycsanjeevanNo ratings yet

- Y3 March Holiday Reivison WorksheetDocument2 pagesY3 March Holiday Reivison WorksheetLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Government Intervention in The Markets PDFDocument11 pagesChapter 4 Government Intervention in The Markets PDFLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- Enzymes - : Quicktime and A Tiff (Uncompressed) Decompressor Are Needed To See This PictureDocument4 pagesEnzymes - : Quicktime and A Tiff (Uncompressed) Decompressor Are Needed To See This PictureLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- Businesstimes 111212 1 PDFDocument1 pageBusinesstimes 111212 1 PDFLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 The Central Problem of Economics and Economic SystemDocument11 pagesChapter 1 The Central Problem of Economics and Economic SystemcsanjeevanNo ratings yet

- Common Vocab ListDocument4 pagesCommon Vocab ListLiling CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- What Does Fedex Deliver?Document17 pagesWhat Does Fedex Deliver?duckythiefNo ratings yet

- ARGA Investment Management L.P.: Valuation-Based Global Equity ManagerDocument1 pageARGA Investment Management L.P.: Valuation-Based Global Equity ManagerkunalNo ratings yet

- Labor Law - Durabuilt Vs NLRCDocument1 pageLabor Law - Durabuilt Vs NLRCEmily LeahNo ratings yet

- Common Rationality CentipedeDocument4 pagesCommon Rationality Centipedesyzyx2003No ratings yet

- Green HolidaysDocument5 pagesGreen HolidaysLenapsNo ratings yet

- Original PDF Global Problems and The Culture of Capitalism Books A La Carte 7th EditionDocument61 pagesOriginal PDF Global Problems and The Culture of Capitalism Books A La Carte 7th Editioncarla.campbell348100% (41)

- Women Welfare Schemes of Himachal Pradesh GovtDocument4 pagesWomen Welfare Schemes of Himachal Pradesh Govtamitkumaramit7No ratings yet

- Blackout 30Document4 pagesBlackout 30amitv091No ratings yet

- Ecotourism Visitor Management Framework AssessmentDocument15 pagesEcotourism Visitor Management Framework AssessmentFranco JocsonNo ratings yet

- Examiners' Report June 2017: GCE Economics A 9EC0 03Document62 pagesExaminers' Report June 2017: GCE Economics A 9EC0 03nanami janinaNo ratings yet

- Research Article StudyDocument2 pagesResearch Article StudyRica Mae DacoyloNo ratings yet

- 43-101 Bloom Lake Nov 08Document193 pages43-101 Bloom Lake Nov 08DougNo ratings yet

- How To Reach Staff Training CentreDocument4 pagesHow To Reach Staff Training CentreRituparna MajumdarNo ratings yet

- How High Would My Net-Worth Have To Be. - QuoraDocument1 pageHow High Would My Net-Worth Have To Be. - QuoraEdward FrazerNo ratings yet

- Informative FinalDocument7 pagesInformative FinalJefry GhazalehNo ratings yet

- Data 73Document4 pagesData 73Abhijit BarmanNo ratings yet

- IPO Fact Sheet - Accordia Golf Trust 140723Document4 pagesIPO Fact Sheet - Accordia Golf Trust 140723Invest StockNo ratings yet

- Trade For Corporates OverviewDocument47 pagesTrade For Corporates OverviewZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Seminar Paper11111Document22 pagesSeminar Paper11111Mulugeta88% (8)

- SBI Statement 1.11 - 09.12Document2 pagesSBI Statement 1.11 - 09.12Manju GNo ratings yet

- Chapter 21 AppDocument2 pagesChapter 21 AppMaria TeresaNo ratings yet

- Downfall of Kingfisher AirlinesDocument16 pagesDownfall of Kingfisher AirlinesStephen Fiddato100% (1)

- Indian Railways Project ReportDocument27 pagesIndian Railways Project Reportvabsy4533% (3)

- IAS 2 InventoriesDocument13 pagesIAS 2 InventoriesFritz MainarNo ratings yet

- Forecasting PDFDocument87 pagesForecasting PDFSimple SoulNo ratings yet

- Urbanized - Gary HustwitDocument3 pagesUrbanized - Gary HustwitJithin josNo ratings yet

- Đề HSG Anh Nhóm 2Document4 pagesĐề HSG Anh Nhóm 2Ngọc Minh LêNo ratings yet

- PT 2 Social ScienceDocument11 pagesPT 2 Social ScienceDevanarayanan M. JNo ratings yet

- Check List For Director ReportDocument3 pagesCheck List For Director ReportAbhishek SharmaNo ratings yet

- Digital Duplicator DX 2430 Offers High-Speed PrintingDocument2 pagesDigital Duplicator DX 2430 Offers High-Speed PrintingFranzNo ratings yet