Professional Documents

Culture Documents

From One Perspective

From One Perspective

Uploaded by

Mario Molina IllescasCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

From One Perspective

From One Perspective

Uploaded by

Mario Molina IllescasCopyright:

Available Formats

From one perspective, he betrays his love for his wife because he refuses to compromise his chivalrous duty.

Also important is the fact that Mlagant is as yet nameless, a technique that Chrtien employs throughout the text to highlight the actions of his characters, so that they are defined by behavior and not by lineage or reputation.

The most resonant moment in this first section of the narrative occurs when Lancelot decides to ride in the pillory cart. It must be understood that Chrtiens audience would immediately understand such a cart as reserved for the most ignoble of criminals. It is not merely suggestive of shame and guilt; it confirms that those who ride it possess such vice. Everything about riding the cart is antithetical to the chivalrous expectations of a medieval knight, who was expected to act always with his reputation in mind. The gravity of taking such a ride is not lost on Lancelot, the paragon of obsessive love; he hesitates before hopping in. In that moment, the author explains that Love and Reason are warring within Lancelot. This personification of emotion is a technique that Chrtien employs readily throughout the text, especially with regard to Lancelot. Reason very rarely, if ever, wins the conflict, and the whole exercise underscores the extent to which Lancelot is impelled by forces beyond himself. This, too, is a central theme of medieval romance.

his decision to ride the cart will saddle him with lower expectations throughout the quest; he will be known as "The Knight of the Cart" until his lover and Queen names him.

As the horse is tied symbolically to virility and sexual appetite, and as horsemanship was considered an essential quality in a knight, this all suggests Lancelot's ineffectiveness and emasculation as both a lover and a knight (Condren 445). As Condren remarks, the particular literary skill in this paradox is Chrtiens strong suggestion that commitment to love has caused the emasculation[which is an example] of a single themethe man whose commitment to one code of conduct unfits him for another (445-446). In other words, Lancelot cannot be both a chivalrous knight and a committed lover. He must emasculate himself as knight to fully devote himself as a lover.

However, he remains a great knight, both in terms of might and mercy. He defeats all of his enemies in his section, but spares the sentinel both from mercy and from his promise to the little girl. In these ways, he remains an ideal representation of chivalrous knighthood. This is a Lancelot very much at odds with the cart-riding, love-sick creature. What is fascinating and ironic, however, is that it is only because of his love-sick nature (manifested in his daydreaming) that he ends up in a position to exhibit these knightly qualities. The author establishes him as a man of

both worlds, and will continue to explore the inner conflict between these qualities as the romance progresses.

The lady steps forward to catch him but realizes that it would be shameful to be saved by a woman, so she desists and claims she stepped forward merely to take the comb.

The son refuses to listen to his fathers reason, so the older man ties the boy up. The challenge now withdrawn, Lancelot and the elegantly dressed woman continue onwards. The lords and ladies in the meadow decide that Lancelot must be honorable after all, if the old knight is willing to let the woman accompany him rather than stay with his own son.

n the first encounter, the bed (symbolic of his relationship with Guinevere) was forbidden and he slept in it anyway, subverting the demands of hospitality and obedience. In this instance, however, fulfilling his hostess's demands requires Lancelot to subvert the demands of fidelity to Guinevere.

The reader might actually pity this poor knight, who is pulled in so many different directions. However, Chrtien comments on Lancelot's discomfort by ironically comparing his silence in bed to that of a monks. Lancelot is anything but a monk (read: chaste). At the moment that the author makes the comparison, Lancelot is lying in the bed of a woman who has offered him hospitality in exchange for sex, while his greater quest is in pursuit of his king's wife. In this one-line, seemingly offhand comparison, the author encodes quite a complex social commentary. Chrtiens genius lies in his subtlety and deft irony.

The retrieval of Guineveres comb demonstrates the obsession of "Our Knight," as Chrtien so often refers to Lancelot. Like he does in the comparison to the monk noted earlier, Chrtien describes Lancelots obsession with the comb in religious terms, describing it as a relic. As his readers would have been both well acquainted with the symbolic and ritual power of true relics, and well aware that religious devotion to such a decidedly secular, lustful object could be considered as tantamount to heresy, the comparison serves doubly to underscore both the depth of Lancelots devotion and the absurdity of it. Lancelot, as scholar A.H. Diverres astutely notes, may be valiant, but he also has one serious weakness: he is lacking a quality considered by Chrtien to be essential to courtly love in a chivalrous setting, namely msure (Diverres in Owen 28). In other words, his virtues may be commendable, but his inability to keep them balanced is a bit ridiculous. He cannot control himself as a lover.

The following night, he lodges with a gracious lady and her lord, who are delighted to host him and the hunting knight's sons. During dinner that knight, an arrogant knightarrives and questions whether a knight who rode in a cart could ultimately achieve success. Lancelot does not respond, but everyone else at the table leaps to his defense, insisting he could not have truly committed a crime (as the cart incident suggests).

Lancelot then climbs onto the blade with bare feet and hands. He is in immense pain as he slowly crosses, but love turned his pain to pleasure

In the course of the conversation, Lancelot again proves himself the rash and devoted lover, choosing to brave the Stony Path even though it is more dangerous, simply because it is faster. Perhaps it is this bravery which inspires the hunting knight's sons to join him as squires. Though they all know of the cart incident, they do not permanently ostracize him, but instead honor him with their presence.

The scene of his captivity is interesting for two reasons. The first is that it allows Chrtien to discuss Lancelot's lineage, reminding his audience that Lancelot was raised by the Lady of the Lake. Such moments have proven crucial towards allowing scholars to construct a cohesive picture of the Arthurian legends, and the connections between characters and incidents. This is particularly central considering the variations in spellings and nomenclature one finds amongst the many romances and stories. Secondly, the fact that Lancelot and his companions immediately suspect magic reminds us how central the belief in such powers were to their world.

If Lancelot is a savior, then those he is meant to save show themselves to be all too human when they argue over who will lodge him. Encoded in their bickering is Chrtien's critique of their gentility. Rather than considering what is best for Lancelot, they selfishly push for their own honor. Chrtien, in the voice of Lancelot, observes: these noises / Youre making tell me the smartest / Man among you is a fool (2476-2478). He again highlights the limitations of strict adherence to the codes that regulated the lives of the medieval gentility. By attempting to conform to the social expectations, they degrade themselves.

Again, Lancelot is asked a favor from a young girl who suddenly arrives. When Mlagants sister (who does not yet identify herself) arrives on a donkey, the image is meant to evoke Christ, who entered Jerusalem on such a humble animal. The comparison, which would not have been lost on medieval audiences, foreshadows her eventual role as Lancelots savior (an event which she hints at in lines 2807-2808). When Bademagu begs Guinevere to intercede for his son, he knows that her words will sway Lancelot. Chrtien writes, Lovers are obedient men, / Cheerfully willing to do / Whatever the beloved, who holds / Their entire heart, desires. / Lancelot had no choice, / For if ever any loved / More truly than Pyramus / It was him (3805-3812). Chrtien here defines Lancelot as a courtly lover, and indeed, the allusion to Pyramus makes it clear that Lancelot is meant to be seen as the ideal courtly lover. Pyramus, who took his life when he thought his lover Thisbe dead, is an archetypal lover, whose story has been alluded to or reworked in countless adaptations, including Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. To compare Lancelot to Pyramus indeed, to suggest that he loved more truly than Pyramus is to quickly and forcefully represent to the audience how Lancelot should be perceived. For all the complications that Chrtien subtly uses to paint Lancelot, he also knew that his audience wanted an unsubtle ideal represented. The expectations of courtly love also help to explain Guineveres scorn for Lancelot. Though it seems surprising, it is totally acceptable within the code of conduct for the female courtly lover (Noble 1972, 534). Lancelot has not shown total devotion (we later learn his grievance was hesitating before leaping into the cart), which means he has loved imperfectly. King Bademagu allows a critique of such behavior when he calls Guinevere capricious over her behavior (line 3995). Considering how closely Bademagu has been presented as an embodiment of Reason, Chrtien suggests through him that such excessive courtly behaviors are unreasonable.

The question of adultery, therefore, is not as straightforward as one might anticipate in such a highly Christian time period. This ambiguity, too, plays into the larger theme of interpretation, by remarking on the limits it imposes on any situation. Lancelot and Guinevere certainly commit adultery, but the romance suggests that their affair transcends conventional morality. However, adultery barely plays into the accusations. As critic Edward I. Condren astutely observes, not even when Guinevere is caught almost literally red handed is her possible shame called adultery. Mlagant, believing that Kay has slept with Guenevere, complains not of the Queens having broken her conjugal obligations but only of Kays having failed in his knightly duty by not guarding her properly (436).

Chrtien leaves the dirtiest details to the imagination, but sex pervades the scene's symbolism. The bloodied curtains and bed are perhaps the most important of these symbols. The blood comes from Lancelots fingers, but bloodied sheets are closely tied to questions of virginity. In some time periods (including the middle ages), a bloodied sheet on a wedding night was taken as proof of a woman's virginity. As Guinevere has been established as virginal through her gown, this symbol serves to reinforce the idea that their love is sanctioned and pure. Of course, the world outside their room considers the blood as a reflection of illicit behavior, again suggesting that the purity of the lover's world stands in stark contrast to the expectations of larger society.

Gawain, as a secondary savior, is a logical choice, but he seems to lack one of Lancelot's primary virtues: love. This is the reason that he was unable to rescue Guinevere. The fact that he was bested by the Sunken Bridge, whereas Lancelot conquered the more dangerous Sword Bridge, suggests that prowess is not enough in this world. Instead, one needs a commitment to Love, the virtue that helped Lancelot cross the Sword Bridge. Nevertheless, Gawain proves himself an honorable knight both when he immediately leaps to Guinevere's aid, and when he refuses to take credit for rescuing her after they return to the court.

Finally, the moment arrives when Lancelot and Guinevere are reunited in happiness. When Lancelot asks about Guinevere's previous coldness, she replies, Didnt the cart / Shame you the least little bit? / You must have hesitated, / For you lingered a good two steps. / And that, you see, was my sole / Reason for ignoring your presence (4491-4496). In other words, she was upset that Lancelot hesitated before leaping in the cart, even though he knew the dwarf would bring him towards her. Lancelot begs her forgiveness, and she grants it.

Guinevere's reaction to Gawain's arrival both confirms her devotion to Lancelot, and reveals her keen sense of duty. Moreso than Lancelot is, Guinevere seems bound and compelled by those courtly codes of conduct which conflict with the demands of true love. Chrtien writes, rejoicing at the sight of Sir Gawain / Was required, and she did her best, despite the overwhelming grief and worry she feels for Lancelot (5203-5204). Lancelot does not have such qualms or compulsions towards fulfilling the code. The closest he has yet come was the two steps of hesitation before leaping into the cart, and whenever that code has conflicted with his love, the latter always triumphs.

Rumors again feature prominently in the tournament scene. Here, the rascally herald's rumors suggest Lancelot's arrival to Guinevere. Rumors are a de rigeur part of court life, and speculation about Lancelots identity grows all the more urgent when he fights well, thus making him a target of the womens matrimonial schemes. Having only a day before despised his very existence, these foolish young women vow to marry nobody but this mysterious knight. The rapidity with and degree to which their opinion of Lancelot changes (What a terrible wrong we committed, / Scoring such a man, / For surely hes worth a thousand / Of anyone out on that field), can be read as an indictment by Chrtien of the vapid and fickle nature of the courtiers who comprised his primary audience (5994-5997). It is also a criticism of virtue based on knightly valor, since that means a man's true character is ignored in favor of his temporary performance on a battlefield.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5811)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Presenting To Win 01-04Document22 pagesPresenting To Win 01-04Mario Molina IllescasNo ratings yet

- Brief Assessments in Child Custody MattersDocument2 pagesBrief Assessments in Child Custody MattersSan Fernando Valley Bar AssociationNo ratings yet

- Juliette BinocheDocument16 pagesJuliette BinocheburkeNo ratings yet

- Can Mindfulness' Really Help You Focus?Document3 pagesCan Mindfulness' Really Help You Focus?Mario Molina IllescasNo ratings yet

- Beo 2Document18 pagesBeo 2Mario Molina IllescasNo ratings yet

- So Much DependsDocument1 pageSo Much DependsMario Molina IllescasNo ratings yet

- Prophet's HairDocument12 pagesProphet's HairMario Molina IllescasNo ratings yet

- Prologue To The Lyrical BalladsDocument2 pagesPrologue To The Lyrical BalladsMario Molina IllescasNo ratings yet

- The Information: A History, A Theory, A FloodDocument1 pageThe Information: A History, A Theory, A FloodMario Molina IllescasNo ratings yet

- Calper Alp CorpusDocument5 pagesCalper Alp CorpusMario Molina IllescasNo ratings yet

- Proceso de Construcción de La (S) Identidad (Es) Raciales en AméricaDocument1 pageProceso de Construcción de La (S) Identidad (Es) Raciales en AméricaMario Molina IllescasNo ratings yet

- SHOLAWAT BADAR (English Subtitle)Document7 pagesSHOLAWAT BADAR (English Subtitle)Ferdian ZamanNo ratings yet

- A Promise Not KeptDocument2 pagesA Promise Not KeptRenu MehraNo ratings yet

- GSIS Case DigestDocument17 pagesGSIS Case DigestMaria Cristina Martinez100% (1)

- FilmDocument14 pagesFilmMindi May AguilarNo ratings yet

- B43 Bristol Myers Company v. Director of Patents, GR L-21587, 19 May 1966, en Banc, Bengzon JP (J)Document1 pageB43 Bristol Myers Company v. Director of Patents, GR L-21587, 19 May 1966, en Banc, Bengzon JP (J)loschudentNo ratings yet

- Capf 2014 FNRSLT EnglDocument5 pagesCapf 2014 FNRSLT EnglsagaravidayaNo ratings yet

- 10 Sample Editorial From The FreemanDocument11 pages10 Sample Editorial From The FreemannocosgemaryNo ratings yet

- Sample Board MeetingDocument2 pagesSample Board MeetingGerry SantosNo ratings yet

- Model de Atestat Limbă Engleză CL - XIIDocument16 pagesModel de Atestat Limbă Engleză CL - XIIŞtefanMoşneaguNo ratings yet

- Konverzacijski EngleskiDocument12 pagesKonverzacijski EngleskiMirko MirkicNo ratings yet

- COMELEC Liquor Ban Resolution 9582Document3 pagesCOMELEC Liquor Ban Resolution 9582tangubnetNo ratings yet

- 18.1 - The Roots of ImperialismDocument33 pages18.1 - The Roots of ImperialismmrmcpheerhsNo ratings yet

- Macalintal V COMELEC DigestDocument2 pagesMacalintal V COMELEC DigestkarenNo ratings yet

- Pride and Prejudice: About The AuthorDocument5 pagesPride and Prejudice: About The Authoranyus1956No ratings yet

- Dream Doesn T Become Reality Through Magic It Takes Sweat Determination and Hard Work Olin OwellDocument11 pagesDream Doesn T Become Reality Through Magic It Takes Sweat Determination and Hard Work Olin OwellAlden GarciaNo ratings yet

- 8 Clat Express December 2017Document32 pages8 Clat Express December 2017venkatesh sahuNo ratings yet

- SMC vs. Puzon, Jr.Document11 pagesSMC vs. Puzon, Jr.Paul PsyNo ratings yet

- Black Sheep v. UMGDocument21 pagesBlack Sheep v. UMGBillboardNo ratings yet

- OET B1 Progress Test Unit 9 A + BDocument8 pagesOET B1 Progress Test Unit 9 A + BЕлена ЛуцкаяNo ratings yet

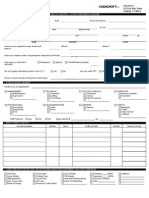

- Application For Employment: Ashcroft Inc. 250 East Main Street Stratford, CT 06614Document5 pagesApplication For Employment: Ashcroft Inc. 250 East Main Street Stratford, CT 06614raffaraffa123No ratings yet

- Ferres A Passage East PDFDocument2 pagesFerres A Passage East PDFShaneNo ratings yet

- James Baldwin - Intro LessonDocument1 pageJames Baldwin - Intro LessonErwan KergallNo ratings yet

- Preventol InfoDocument2 pagesPreventol InfoInderpreetKaurMaanNo ratings yet

- GV Florida Vs BattungDocument3 pagesGV Florida Vs BattungFRANCISNo ratings yet

- Aznar v. Citibank G.R. No. 163273, March 28, 2007Document2 pagesAznar v. Citibank G.R. No. 163273, March 28, 2007Jeremiah De LeonNo ratings yet

- Concession Theory - The Corporation Is A Creature Without Existence Until It Has Received Imprimatur of The State Acting According To Law. 2Document5 pagesConcession Theory - The Corporation Is A Creature Without Existence Until It Has Received Imprimatur of The State Acting According To Law. 2Shane JardinicoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To VipassanaDocument4 pagesIntroduction To VipassanaBabu BalaramanNo ratings yet

- Public International Law Project Custom As A Source of International LawDocument17 pagesPublic International Law Project Custom As A Source of International LawVicky DNo ratings yet