Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Antiplatelet Agents in Acute Non-ST Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes

Antiplatelet Agents in Acute Non-ST Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes

Uploaded by

César Santis FuentesCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Antiplatelet Agents in Acute Non-ST Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes

Antiplatelet Agents in Acute Non-ST Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes

Uploaded by

César Santis FuentesCopyright:

Available Formats

Antiplatelet agents in acute non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes Authors Michael Simons, MD Donald Cutlip, MD A Michael Lincoff,

MD Section Editors Christopher P Cannon, MD Freek Verheugt, MD, FACC, FESC Deputy Editor Gordon M Saperia, MD, FACC Disclosures All topics are updated as new evidence becomes available and our peer review process is complete.

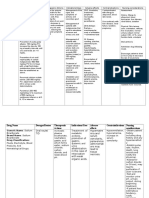

Literature review current through: Oct 2013. | This topic last updated: oct 3, 2013. INTRODUCTION Rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque is the usual initiating event in an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Plaque rupture often leads to thrombus formation and persistent thrombotic occlusion results in acute myocardial infarction (MI). (See "The role of the vulnerable plaque in acute coronary syndromes".) The role of platelets in thrombus formation during ACS is discussed in detail elsewhere (figure 1). (See "Congenital and acquired disorders of platelet function", section on 'Normal platelet function' and "The role of platelets in coronary heart disease".) This topic will discuss the use of antiplatelet agents in unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction, which together are referred to as non-ST elevation ACS. All patients with non-ST elevation ACS should be treated with aspirin and a platelet P2Y12 receptor blocker. The use of antiplatelet agents in ST-elevation MI is discussed separately. (See "Antiplatelet agents in acute ST elevation myocardial infarction".) CLASSIFICATION OF ANTIPLATELET AGENTS Antiplatelet agents interfere with a number of platelet functions, including aggregation, release of granule contents, and platelet-mediated vascular constriction. They can be classified according to their mechanism of action (figure 2): Aspirin blocks cyclooxygenase (prostaglandin H synthase), the

enzyme that mediates the first step in the biosynthesis of prostaglandins and thromboxanes (including TxA2) from arachidonic acid (algorithm 1). The P2Y12 receptor blockers, clopidogrel, ticlopidine, prasugrel, ticagrelor, and cangrelor block the binding of adenosine diphosphate (ADP) to a platelet receptor P2Y12, thereby inhibiting activation of the glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa complex and platelet aggregation [1]. Anti-GP IIb/IIIa antibodies and receptor antagonists inhibit the final common pathway of platelet aggregation (the cross-bridging of platelets by fibrinogen binding to the GP IIb/IIIa receptor) and may also prevent adhesion to the vessel wall. ASPIRIN Aspirin has an established benefit in a variety of cardiovascular disorders including primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease, transient ischemic attack, and stroke, and in the acute therapy of patients with an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). (See "Benefits and risks of aspirin in secondary and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease".) The antiplatelet activity of aspirin appears to be mediated principally through inhibition of the synthesis of thromboxane A2 (TxA2), a potent stimulator of platelet aggregation (see "Overview of hemostasis", section on 'Platelet aggregation') [2]. Since platelets do not synthesize new enzymes, the functional defect induced by aspirin persists for the life of the platelet. (See "Benefits and risks of aspirin in secondary and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease", section on 'Mechanisms of action'.) Evidence of benefit The Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration reviewed the effect of antiplatelet therapy, mostly aspirin (in doses ranging from 75 to 1500 mg daily) in nearly 200,000 patients [3]. Antiplatelet therapy produced a significant 46 percent reduction in the combined end point of subsequent nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), nonfatal stroke, or vascular death (8.0 versus 13.3 percent) in patients with unstable angina, and a 30 percent reduction in patients with acute myocardial infarction (10.4 versus 14.2 percent) (table 1). There was no significant difference in efficacy between lower and higher daily doses (75 to 325 versus 500 to 1500 mg). Another important contribution of this analysis was the finding

that the addition of a second antiplatelet agent (eg, dipyridamole, ticlopidine, or intravenous glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor) significantly lowered the combined end point. Dose An initial loading dose of 162 to 325 mg of uncoated aspirin should be given as soon as possible to any patient thought to have an ACS. At this dose, aspirin produces a rapid antithrombotic effect due to immediate and almost complete inhibition of thromboxane A2 production. The first tablet should be chewed or crushed to establish a high blood level quickly. More rapid absorption occurs with nonenteric coated formulations. There is no evidence that higher doses are more effective but they may lead to greater gastric irritation. Aspirin (75 to 100 mg once a day) should be continued indefinitely for secondary prevention [4]. The upper limit of 100 mg is based on the observation of a dose dependent increase in the rate of major bleeding in the CURE trial: 2, 2.3, and 4 percent at doses of than 100, 100 to 200, and greater than 200 mg daily [5]. (See "Benefits and risks of aspirin in secondary and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease", section on 'Dosing and cardiovascular benefit' and "Benefits and risks of aspirin in secondary and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease", section on 'Dosing and bleeding risk' and 'Clopidogrel' below.) We recommend that ACS patients be discharged on 75 to 100 mg/day of aspirin, based principally on CURRENT OASIS 7 trial, in which there was no significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes between high or low dose aspirin irrespective of whether ACS patients received percutaneous coronary intervention or not, while gastrointestinal bleeding rates were increased with higher dose aspirin. For patients taking ticagrelor, we recommend not using doses greater than 100 mg daily. (See 'Ticagrelor' below.) Side effects and allergy Aspirin therapy may be associated with gastrointestinal intolerance or bleeding, allergy (primarily manifested as bronchospasm or asthma), and worsening of pre-existent bleeding. Gastrointestinal side effects such as dyspepsia and nausea are infrequent with the low doses. Patients who develop gastrointestinal side effects should be treated with a proton pump inhibitor and are usually able to tolerate a lower and probably still effective dose (80 to 100 mg of aspirin per day) [6]. Enteric-coated aspirin may be of some benefit, but it does not protect against gastrointestinal bleeding. (See "Benefits and risks of aspirin in secondary and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease", section on 'Aspirin formulation' and "Periprocedural and long-term gastrointestinal bleeding in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention" and "Diagnostic challenge and desensitization protocols for NSAID reactions".)

Summary An initial loading dose of 162 to 325 mg of uncoated aspirin should be given as soon as possible to any patient thought to have an ACS. We recommend that ACS patients be discharged on 75 to 162 mg/day of aspirin. For patients taking ticagrelor, we suggest aspirin at a dose between 75 and 100 mg daily. (See 'Ticagrelor' below.) PLATELET P2Y12 RECEPTOR BLOCKERS Clopidogrel, ticlopidine, prasugrel, ticagrelor, and cangrelor block the adenosine diphosphate receptor P2Y12 on platelets. (See "Platelet biology".) The evidence presented below supports a strong recommendation for at least one year of dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and a P2Y12 receptor blocker in all patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). This recommendation is based principally on the results of the CURE trial, which compared dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel to aspirin alone. Evidence for the role of ticagrelor and prasugrel comes from studies which compared these newer agents to clopidogrel. Ticlopidine is rarely chosen due to the risk of thrombocytopenia. Three limitations to the use of clopidogrel (delayed onset of action, large between individual variability in platelet response, and irreversibility of its inhibitory effect on platelets) led to the development of other agents, including prasugrel and ticagrelor [7]. Both prasugrel and ticagrelor induce more intense platelet inhibition than clopidogrel and have been found to be both more effective and associated with higher rates of bleeding. All trials of P2Y12 receptor blockers have given these drugs in conjunction with aspirin. Clopidogrel The benefit of dual antiplatelet was established in the CURE trial, which randomly assigned 12,562 patients who presented within 24 hours after the onset of a non-ST elevation ACS to aspirin alone (75 to 325 mg/day) or with clopidogrel (300 mg loading dose immediately followed by 75 mg/day) for 9 to 12 months; both were given immediately on presentation. The majority of patients were at increased risk of an adverse outcome because of electrocardiogram (ECG) changes (mostly ST depression 1 mm or T wave inversion 2 mm) or elevated cardiac enzymes [5]. Over 60 percent did not receive revascularization. The primary endpoint was cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or

stroke. At an average follow-up of nine months, combination therapy led to a significant reduction in the combined primary endpoint of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke (9.3 versus 11.4 percent), which was largely due to fewer MIs (5.2 versus 6.7 percent) (figure 3). However, clopidogrel therapy significantly increased the rate of major bleeding (3.7 versus 2.7 percent) but not in life-threatening bleeding or hemorrhagic stroke. Clopidogrel therapy produced a similar relative risk reduction in patients who were treated medically or underwent revascularization [8] and in low-, intermediate-, and high-risk patients as defined by the TIMI risk score (calculator 1) [9]. High-risk patients derived the greatest absolute benefit. A subsequent analysis from CURE evaluated the time course of benefit of clopidogrel [10]. Evidence of benefit began to emerge within 24 hours and gradually increased in magnitude during the first 30 days (4.3 versus 5.4 percent incidence of the primary endpoint, relative risk 0.79). The benefit continued to increase from 31 days to one year (5.2 versus 6.3 percent incidence of new events, relative risk 0.82) (figure 4). There was no significant excess of late life-threatening bleeding, but there was a small excess of major bleeds (5 per 1000) that was much smaller than the total cardiovascular benefit at one year (22 per 1000). Subgroup analyses of the CURE (PCI-CURE) [8] and the CREDO trials [11] have confirmed the benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel in ACS patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stenting. (See "Antithrombotic therapy for intracoronary stent implantation: Clinical trials", section on 'Timing and dose'.) Dose The standard clopidogrel regimen in patients with a non-ST elevation ACS, which was used in CURE and CREDO, has been a 300 mg loading dose followed by a maintenance dose of 75 mg/day [5,8,11]. However, the benefit in CREDO was only seen in patients who had been treated at 15 hours before PCI [12]. This concern existed for non-ACS patients as well and led to the following studies that compared a 300 mg to a 600 mg loading dose (see "Antithrombotic therapy for intracoronary stent implantation: Clinical trials", section on 'Timing and dose'): In the ARMYDA-trial in which 255 patients (75 percent stable angina, 25 percent non-ST elevation ACS) scheduled to undergo PCI were randomly assigned to a 300 or 600 mg loading dose four to eight

hours before the procedure [13]. The primary end point (death, MI, or target vessel revascularization) occurred significantly less often with the 600 mg loading dose (4 versus 12 percent). In a single center trial in which 292 patients with non-ST elevation ACS were randomly assigned to either 300 or 600 mg at least 12 hours before scheduled stenting, the rate of recurrent cardiovascular events at 30 days was significantly lower with the 600 mg dose (5 versus 12 percent) [14]. The optimal loading dose of clopidogrel in patients with ACS was best addressed in the CURRENT-OASIS 7 trial, which randomly assigned 25,086 patients with an ACS (70.8 percent unstable angina or non-ST elevation myocardial infarction [NSTEMI]) referred for an invasive strategy to either clopidogrel 600 mg loading dose on day one followed by 150 mg daily for six days (and 75 mg thereafter) or clopidogrel 300 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg daily [15]. The interval between randomization and PCI was 3.4 hours. The following findings were noted: The rate of the primary outcome (cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke at 30 days) was not statistically different (4.2 versus 4.4 percent respectively). However, in the subgroup of patients who underwent PCI (n = 17,263) the higher dose of clopidogrel significantly reduced the rate of the primary outcome, 3.9 versus 4.5 percent; adjusted hazard ratio 0.86, 95% CI 0.74-0.99. Major bleeding occurred significantly more often in patients who received the higher clopidogrel dose (2.5 versus 2.0 percent in the overall population and 1.6 versus 1.1 in the PCI subgroup). The higher dose of clopidogrel was associated with a significant reduction in the secondary outcome of definite or probable stent thrombosis among the 17,263 patients who underwent PCI (1.6 versus 2.3 percent) [16]. (See "Antiplatelet therapy after coronary artery stenting".)

We recommend a 600 mg loading dose in patients who will undergo angiography and possible revascularization within 24 hours of diagnosis. (See "Antithrombotic therapy for percutaneous coronary intervention: General use" and "Antithrombotic therapy for intracoronary stent implantation: Clinical trials", section on 'Timing and dose'.) We prefer the maintenance dose of 75 mg daily, as opposed to the higher dose of 150 mg for six days. As the evidence supporting the 150 mg dose (for one week) comes from a subgroup analysis of a negative trial (CURRENT-OASIS 7), the lower dose is preferred until further evidence is available. We are concerned of an increase in the frequency of bleeding with the higher dose. Patients already taking clopidogrel The issue of clopidogrel reloading is discussed separately. (See "Antithrombotic therapy for percutaneous coronary intervention: General use", section on 'Patients already taking clopidogrel'.) Duration of therapy The CURE trial discussed above provides evidence that dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel should be continued for 9 to 12 months. While studies have not compared one duration of therapy to another, the continued separation of events in CURE up to 9 to 12 months (figure 3) makes us reasonably confident about this duration. This minimum duration is supported by a retrospective cohort study of ACS patients treated with stents (1569, 63 percent received bare metal stents) and without stents (1568) which evaluated the frequency and timing of both all-cause mortality or acute MI after clopidogrel cessation [17]. The mean duration of clopidogrel therapy was 278 and 302 days, respectively. In multivariate analysis, including adjustment for duration of clopidogrel treatment, the first 90-day interval after stopping clopidogrel treatment was associated with a small risk of adverse events in both medical and PCI groups (1.31 and 0.57 per 1000 patient-days, respectively) that was significantly higher than in the interval of 91 to 180 days (incidence rate ratios 1.82 and 1.98). This early incidence of adverse events was consistent whether patients took clopidogrel for three, six, or nine or more months. Evidence from randomized trials in favor of continued clopidogrel use for longer than one year in non-ST elevation ACS is lacking. However, some support comes from the CAPRIE trial, which compared clopidogrel to aspirin (but not the combination) in patients with atherosclerosis not limited to acute coronary syndromes [18]. Clopidogrel therapy was associated with a significant reduction in fatal or nonfatal MI; the magnitude of this

benefit increased progressively over the three-year period of the study [19]. Support also comes from subgroup analyses from CHARISMA, where benefit was seen in patients with prior MI or stroke [20]. Some physicians recommend continuing clopidogrel beyond one year or even indefinitely given a continued benefit over time observed in CURE, PCI-CURE (figure 5), and CREDO (figure 6) [5,8,11]. This approach should be considered in patients with more severe vascular disease (eg, prior MI or cerebrovascular event or peripheral vascular disease) or in those with drug-eluting stents. (See "Antiplatelet therapy after coronary artery stenting" and "Antiplatelet therapy after coronary artery stenting", section on 'Duration'.) After CABG The use of clopidogrel in patients with non-ST elevation ACS undergoing urgent coronary artery bypass graft surgery is discussed separately. (See "Medical therapy to prevent complications after coronary artery bypass graft surgery", section on 'Platelet P2Y12 receptor blocker therapy'.) Ticlopidine Ticlopidine compared to placebo improves outcomes in patients with unstable angina who are not treated with aspirin [21]. No trials have compared ticlopidine to aspirin or assessed the role of combined therapy. Side effects have limited its use compared to clopidogrel. (See "Antithrombotic therapy for percutaneous coronary intervention: General use", section on 'Ticlopidine'.) Prasugrel Prasugrel has a more rapid onset of action and is able to achieve higher degrees of platelet inhibition than clopidogrel [22,23]. Furthermore, prasugrel effectively suppresses platelet activity in a larger numbers of patients than clopidogrel, since 20 to 25 percent of patients appear to be clopidogrel-resistant. (See "Clopidogrel resistance and clopidogrel treatment failure", section on 'Definitions'.) Patients undergoing PCI The TRITON-TIMI 38 trial directly compared prasugrel to clopidogrel in 13,608 moderate- to high-risk ACS patients undergoing PCI, including 10,074 with non-ST elevation ACS [24]. Prasugrel was given with a loading dose of 60 mg and maintenance dose of 10 mg/day while clopidogrel was given with a 300 mg loading dose and a 75 mg/day maintenance dose; the median duration of therapy was 14.5 months. For patients with unstable angina or NSTEMI, the coronary anatomy had to be known before randomization. Thus, in the majority of cases both clopidogrel and prasugrel were given after coronary angiography. At 15-month follow-up, the following findings were noted (the overall data

are given since the benefits were similar in non-ST elevation and ST elevation syndromes): The primary efficacy end point (cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke) occurred significantly less often in patients treated with prasugrel (9.9 versus 12.1 percent; hazard ratio [HR] 0.81; 95% CI 0.73-0.90) irrespective of whether or not they underwent PCI with stenting [24,25]. This was driven primarily by a significant reduction in nonfatal MI (7.4 versus 9.7 percent). Among patients who sustained a nonfatal MI or stroke, the likelihood of a recurrent primary end point was significantly reduced with prasugrel compared to clopidogrel (10.8 versus 15.4 percent), as was the likelihood of cardiovascular death following the nonfatal first event (3.7 versus 7.1 percent) [26]. This benefit was found in patients with either procedure-related or non-procedure related MIs and was seen irrespective of MI size or timing [27]. The safety end point of a major bleeding event not associated with coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) occurred significantly more often in patients treated with prasugrel (2.4 versus 1.8 percent; HR 1.32; 95% CI 1.03-1.68). This difference was attributable to an increase in bleeding events with prasugrel after (but not before) the first three days [28]. The rate of life-threatening bleeding was also significantly increased with prasugrel. Post hoc analysis identified three predictors of less net clinical efficacy and greater absolute levels of bleeding with prasugrel: A history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA); age 75 years of age; and body weight 60 kg. In those with stroke or transient ischemic attack, the use of prasugrel was associated with harm. The United States Food and Drug administration states the following: Prasugrel use is contraindicated in patients with active pathologic bleeding or history or TIA or stroke.

The rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis (ARC definition) was significantly reduced in the prasugrel group (1.1 versus 2.4 percent). (See "Coronary artery stent thrombosis: Incidence and risk factors", section on 'Definitions'.) There are no data on the efficacy or safety of pre-PCI loading with prasugrel in patients with non-ST elevation MI. We do not recommend use in that setting. (See "Coronary artery stent thrombosis: Incidence and risk factors", section on 'Risk factors' and 'Timing' below.) Patients not undergoing PCI The TRILOGY ACS trial directly compared prasugrel to clopidogrel in 9326 patients treated with aspirin with unstable angina or NSTEMI in whom PCI was not performed [29]. Randomization was carried out more than four days after admission. Prasugrel was given with a loading dose of 30 mg and a maintenance dose of 10 mg/day in patients less than 75 years or 5 mg/day for those 75 years or older or weighed less than 60 kg; clopidogrel was given with a 300 mg loading dose and a 75 mg/day maintenance dose. The primary efficacy end point was a composite of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke among patients under the age of 75 years. The median duration of exposure to a study drug was 14.8 months. During a median follow-up of 17.1 months, the following findings were noted: There was no statistically significant difference in the rate of the primary end point in the 7243 patients under the age of 75 years between those who received prasugrel and those who received clopidogrel (13.9 versus 16.0 percent; hazard ratio [HR] 0.91, 95% CI 0.79-1.05). The rates of severe and intracranial bleeding were not statistically significantly different. However, irrespective of which bleeding criteria was applied, the event rates at 30 days tended to be higher with prasugrel and the confidence intervals for the hazard ratios for bleeding often included upper boundaries that indicated as much as a doubling of the risk. As expected, a separate analysis of the 2083 individuals 75 years of age found that the risks of the primary end point and of Thrombolysis

in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) major bleeding increased progressively with age and were two to threefold higher in older individuals [30]. Similar to the entire study population, there was no significant difference in these outcomes between the two interventions in these older patients. A prespecified subgroup analysis evaluated outcomes based on whether or not diagnostic angiography had been performed [31]. Although the primary end point was lower in the prasugrel group than in the clopidogrel group for those who had angiography (10.7 versus 14.9 percent; adjusted hazard ratio 0.77, 95% CI 0.61-0.98), the finding of this positive result in an overall negative trial may be spurious. Dosing in elderly The optimal dose of P2Y12 receptor blockers in elderly patients who are at increased bleeding risk is not known. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (phase 1b) GENERATIONS trial of stable patients found that prasugrel 5 mg in 79 elderly patients (mean age of 79 years) was noninferior to prasugrel 10 mg in 56 nonelderly patients (mean age of 56 years) for the primary end point of maximum platelet aggregation [32]. Bleeding rates were comparable, but the study was not powered for clinical effectiveness or safety outcomes. Ticagrelor Ticagrelor differs from the thienopyridines (clopidogrel and prasugrel) in that it binds reversibly rather than irreversibly to P2Y12 platelet receptor and has a more rapid onset of action than clopidogrel [7]. It has been assigned to a new chemical class of antiplatelet agents, the cyclopentyltriazolopyrimidines. Similar to prasugrel, treatment with ticagrelor leads to more intense platelet inhibition than clopidogrel. The efficacy and safety of ticagrelor were evaluated in the PLATO trial in which 18,624 patients with ACS were randomly assigned to either ticagrelor (180 mg loading dose followed by 90 mg twice daily) or clopidogrel (300 to 600 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg daily) [33]. Treatment was started as soon as possible after hospital admission (median of five hours), but many patients received the drug after coronary angiography. The median time from the first dose of the study drug to PCI was approximately 4 hours (interquartile range [approximately] 0.45-50.8 hours). All patients received a loading dose of aspirin, which was usually 325 mg.

Subsequently, all patients received chronic aspirin therapy; the protocolspecified maintenance dose was 75-100 mg daily for patients not undergoing stenting and allowed the use of up to 325 mg daily for up to six months in those who did. The final diagnosis of ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), NSTEMI, or unstable angina (UA) was present in 38, 43 and 17 percent of patients respectively. The intent to perform PCI was mandated for patients with STEMI, but not for those with NSTEMI or UA. Thus, PLATO included patients who were managed medically. At 12 months, the composite primary end point (first event of death from vascular causes, MI, or stroke) occurred significantly less often in patients receiving ticagrelor (9.8 versus 11.7 percent, hazard ratio [HR] 0.84, 95% CI 0.77-0.92). There was no significant difference in the rates of major bleeding between the ticagrelor and clopidogrel groups (11.6 versus 11.2 percent respectively), but ticagrelor was associated with a significantly higher rate of major bleeding not related to coronary artery bypass grafting (4.5 versus 3.8 percent). The following are findings from analyses of subgroups or secondary end points in PLATO: In an analysis that evaluated all events in the primary composite outcome, including first (1888 patients) and recurrent events (318 patients), ticagrelor significantly reduced the total number of events (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.79-0.93) [34]. A prespecified, subgroup analysis found a potentially clinically important interaction between treatment and region: the composite primary end point occurred more often with ticagrelor for patients enrolled in the United States (12.6 versus 10.1 percent, HR 1.27, 95% CI 0.93-1.75) [35]. Among 37 baseline and postrandomization factors, only aspirin dose explained a substantial fraction (80-100 percent) of the interaction (p=0.00006). The hazard ratios comparing ticagrelor and clopidogrel for the primary efficacy outcome, according to region and daily dose category for median maintenance aspirin, are as follows: United States, 300 mg: 1.62 (95% CI 0.99-2.64)

United States, 100 mg: 0.73 (95% CI 0.40-1.33) Non-United States, 300 mg: 1.23 (95% CI 0.71-2.14) Non-United States, 100 mg: 0.78 (95% CI 0.69-0.87) Until further data confirms or refutes the findings of a potential negative interaction between ticagrelor and high-dose aspirin, we suggest that when aspirin is used in conjunction with ticagrelor for the treatment of ACS, it be administered only at a daily dose of 100 mg, including patients who undergo stenting.

The primary outcome was similar to the entire study population in three prespecified subgroups: patients with chronic kidney disease (17.3 versus 22 percent respectively; HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.65-0.90) [36]; patients who underwent coronary artery bypass graft surgery and were receiving study drug treatment less than seven days before surgery (10.6 versus 13.1 percent; HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.60-1.16) [37]; and patients with a planned non-invasive management (12.0 versus 14.3 percent; HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.73-1.00) [38]. In addition, among patients who underwent PCI in PLATO, outcomes were similar in patients who received clopidogrel pre-randomization and those who did not [39]. Among the 11,289 stented patients with any ACS, the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis was significantly reduced with ticagrelor (2.21 versus 2.87 percent; HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.59-0.95) [40]. (See

"Coronary artery stent thrombosis: Incidence and risk factors", section on 'Definitions'.) Cangrelor Cangrelor is an intravenous P2Y12 receptor blocker that has been compared to either clopidogrel or placebo in three randomized trials that included patients with non-ST elevation coronary syndrome (NSTEACS) and evaluated 48-hour outcomes. As cangrelor has not been directly compared to either ticagrelor or prasugrel, which are preferred in this patient population (see 'Invasive approach' below), we do not recommend its use in patients with STEMI. (See "Antithrombotic therapy for intracoronary stent implantation: Clinical trials", section on 'Cangrelor'.) Timing For most NSTEACS patients scheduled to undergo an invasive approach, we suggest that the platelet P2Y12 receptor blocker (either ticagrelor or clopidogrel) be given at the time of diagnosis rather than after diagnostic angiography. It is reasonable to withhold treatment until after diagnostic coronary angiography in some patients, such as those at very high bleeding risk, those who have a high likelihood of needing urgent coronary artery bypass graft surgery (eg, prior coronary anatomy known), or those at low risk of a cardiovascular event in the short term (eg, negative troponin, non-diagnostic changes on an electrocardiogram, and less than a few hours to catheterization). There are no studies of clopidogrel or ticagrelor that directly compare preangiography to postangiography administration in patients with NSTEACS. Thus, the rationale for the recommendation for early treatment with either ticagrelor or clopidogrel in NSTEACS patients undergoing an invasive approach is based principally on three indirect pieces of evidence: The finding of an early reduction in events in the CURE trial (see 'Clopidogrel' above). In the CURE trial, which compared clopidogrel plus aspirin to aspirin alone, the event rates in the two arms diverged within a few hours [10]. The absolute event rates were low during the first few hours and thus the absolute number of events prevented by dual antiplatelet therapy was small. A 2012 meta-analysis indirectly evaluated the optimal timing of clopidogrel in patients undergoing PCI using data from six randomized trials and nine observational studies of both ACS and stable patients [41]. The principal analysis was limited to the

randomized trials, in which 75 percent of patients had NSTEACS. Clopidogrel pretreatment, compared to treatment after catheterization, was not associated with a reduction in mortality (absolute risk 1.54 versus 1.97 percent, respectively, odds ratio [OR] 0.80, 95% CI 0.57-1.11) but was associated with a lower risk of a secondary composite end point of death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or urgent revascularization (9.83 versus 12.35 percent, OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.66-0.89). Bleeding rates were comparable (3.57 versus 3.08 percent). In the PLATO trial, which compared ticagrelor to clopidogrel in ACS patients, most individuals received ticagrelor or clopidogrel before angiography (see 'Ticagrelor' above). With regard to prasugrel, we do not recommend that it be given prior to angiography since, in the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial, which established the superiority of prasugrel to clopidogrel, both were given after angiography, unlike the PLATO trial in which the P2Y12 receptor blockers were given before angiography. (See 'Patients undergoing PCI' above.) However, there is one trial comparing early to late use of prasugrel. The ACCOAST trial randomly assigned 4033 patients with NSTEMI who were scheduled to undergo an invasive approach within 2 to 48 hours to prasugrel 30 mg before angiography or placebo [42]. For patients undergoing PCI after angiography, an additional 30 mg was given to those in the pretreatment group and 60 mg to those given placebo, and all patients received prasugrel 10 mg daily thereafter; P2Y12 therapy for those treated medically or with CABG was left to the discretion of the investigator. PCI was performed at a mean time of 4.3 hours after the initial loading dose. The trial was stopped early because of the finding of harm. At seven days, the rate of the primary composite efficacy end point (death from cardiovascular causes, MI, stroke, urgent revascularization, or glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor rescue therapy) was similar in the two groups (10.0 versus 9.9 percent, respectively; hazard ratio 1.02, 95% CI 0.84-1.25). However, the rate of the key safety end point of all Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) major bleeding (table 2) episodes was greater with pretreatment (2.6 versus 1.4 percent; hazard ratio 1.90, 95% CI 1.19-3.02). The results were similar in the subgroup of patients undergoing PCI. For patients undergoing a conservative approach (no intended revascularization), we suggest that either clopidogrel or ticagrelor be given as soon as possible after the diagnosis. (See 'Summary' below.)

Bleeding risk The most important common side effect associated with platelet P2Y12 receptor blocker therapy is bleeding. The combination of clopidogrel plus aspirin in CURE (see 'Clopidogrel' above) was associated with a significant increase in major (3.7 versus 2.7 percent with aspirin alone), minor (5.1 versus 2.4 percent), and gastrointestinal bleeding (1.3 versus 0.7 percent), but not life-threatening bleeding events at 12 months [5]. (See "Antithrombotic therapy for intracoronary stent implantation: Clinical trials", section on 'P2Y12 receptor blockers'.) Risk factors for bleeding with a P2Y12 receptor blocker include a history of transient ischemic attack or stroke, age 75 years, propensity to bleed (eg, recent trauma or surgery, recent or recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding, active peptic ulcer disease, severe hepatic impairment) body weight <60 kg, or concomitant use of medications that increase risk (oral anticoagulants or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs). In addition the risk of bleeding is increased with ticagrelor and prasugrel compared to clopidogrel. A history of active gastrointestinal bleeding presents a challenge to the care of the patient with ACS. The discussion of the incidence, risk factors, outcomes, prevention, and treatment of periprocedural gastrointestinal bleeding is found elsewhere. (See "Periprocedural and long-term gastrointestinal bleeding in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention".) One factor that influences our recommendations for the choice of P2Y12 receptor blocker is the rate of bleeding for each drug. The rate of major bleeding with prasugrel was higher than that for clopidogrel in TRITONTIMI 38 trial. In PLATO, there was no significant difference in the rates of major bleeding between the ticagrelor and clopidogrel groups, but ticagrelor was associated with a significantly higher rate of major bleeding not related to coronary artery bypass grafting. There are no published studies that directly compare the rates of bleeding between ticagrelor and prasugrel. However, based on pharmacokinetic data, which suggest that the duration of inhibitory effect is shorter with ticagrelor, and the findings from PLATO and TRITON-TIMI 38, we are concerned that bleeding rates are higher with prasugrel. In addition, prasugrel was given only to a subset of all non-ST elevation ACS patients (those who were post angiography about to undergo PCI) in TRITON-TIMI 38 and not at the time of presentation in the emergency department, whereas ticagrelor was given to all patients with ACS. We are concerned that patients in TRITON-TIMI 38 were a lower risk group than those in PLATO since high risk patients may have been excluded from enrollment.

Thus, we have no information on the rate of bleeding if prasugrel were given to a higher risk group at the earlier time point, when many other antithrombotics are being given and the patients are more unstable. Early CABG The concern for an increased risk of bleeding, discussed above, is particularly relevant in non-ST ACS patients who undergo early CABG. The likelihood of life-threatening or major bleeding within seven days of CABG was non-significantly increased in patients in the CURE trial who had received clopidogrel within the five days prior to CABG (9.6 versus 6.3 percent with placebo), but not in those who had discontinued clopidogrel 5 days prior to CABG (4.4 versus 5.3 percent) [43]. This finding is supported by several observational studies [44-48]. (See "Early noncardiac complications of coronary artery bypass graft surgery", section on 'Bleeding'.) In the TRITON-TIMI 38 [24] and PLATO [33] trials of P2Y12 receptor blocker therapy, the risk of CABG related major bleeding was significantly increased with prasugrel but not ticagrelor compared to clopidogrel (13.4 versus 3.2 percent and 7.4 versus 7.9 percent, respectively). (See 'Prasugrel' above and 'Ticagrelor' above.) Any excess bleeding risk due to recent P2Y12 receptor blocker use in the minority of patients who will or might require CABG must be weighed against the potentially deleterious effect of delaying or not administering such therapy [49]. In subgroup analyses of patients undergoing CABG in the ACUITY and CURE trials [43,50], patients with ACS who received clopidogrel had a lower rate of adverse outcomes than those who did not. For instance, in ACUITY, the rate of the primary composite outcome at 30 days was significantly less in those who received clopidogrel compared to those who did not (12.7 versus 17.3 percent) [50]. (See "Anticoagulant therapy in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes", section on 'Bivalirudin'.) A 2011 systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated outcomes from over 10 heterogenous studies that included ACS patients who underwent CABG on or off clopidogrel [51]. In those with clopidogrel exposure within five days of CABG, the rates of death, stroke, and the combined rate of death, stroke, and myocardial infarction were non-significantly higher (odds ratios 1.44, 95% CI 0.97-2.13, 1.23, 95% CI 0.66-2.29, and 1.10, 95% CI 0.87-1.41, respectively). We believe there is insufficient evidence to allow for firm conclusions regarding benefit to risk ratio for continuing P2Y12 receptor blocker until the time of CABG. For most patients we suggest discontinuing such therapy before CABG (at least five days for clopidogrel and ticagrelor and

at least seven days for prasugrel). As the return of normal platelet function occurs more quickly after cessation of ticagrelor than clopidogrel (as determined by measurements of platelet function), some experts are comfortable allowing patients to undergo CABG as soon as three days after cessation. Non-bleeding adverse effects Three important nonbleeding side effects of P2Y12 receptor blocker use have been identified: neutropenia and thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome (TTP-HUS), both of which are primarily described with ticlopidine, and hypersensitivity, which is more common with clopidogrel. These issues are discussed separately. (See "Antithrombotic therapy for percutaneous coronary intervention: General use".) Summary Outcomes after non-ST elevation ACS are better with aspirin plus a platelet P2Y12 receptor blocker than with aspirin alone, irrespective of whether patients are managed with invasive or conservative strategies. Dual antiplatelet therapy should be given as soon as possible after diagnosis and continued for one year. In addition, evidence from TRITONTIMI 38 (prasugrel) and PLATO (ticagrelor) provides strong support for the general idea that agents with higher levels of platelet inhibition have lower cardiovascular event rates but higher rates of bleeding compared to clopidogrel [24]. In patients undergoing an invasive approach, we believe the evidence from TRITON-TIMI 38 and PLATO, which came to similar conclusions, supports the use of ticagrelor or prasugrel rather than clopidogrel in most patients with non-ST elevation ACS. This preference for ticagrelor or prasugrel instead of clopidogrel is made in the 2011 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of ACS in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation [52]. However, this preference differs from recommendations made in the 2012 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation MI, which lists the three P2Y12 receptor blockers without making a preference (for patients managed with an invasive strategy) [53]. While there are no randomized trials that compare ticagrelor to prasugrel, we prefer ticagrelor in most cases. Issues of cost or availability may influence choice. For patients managed with an invasive approach, the choice of P2Y12 receptor blocker depends on when the drug is given: For patients in whom the drug is withheld until the coronary anatomy is known, we prefer either ticagrelor or prasugrel to clopidogrel.

For patients in whom the drug is given at the time of diagnosis, we prefer ticagrelor to prasugrel, as the early use of the latter has not been evaluated. For those patients who have received clopidogrel prior to diagnostic angiography or who have been taking clopidogrel long-term, we suggest switching to ticagrelor (with the 180 mg loading dose) prior to or after PCI. In patients not undergoing an invasive approach, the relative efficacy and safety of ticagrelor compared to clopidogrel and prasugrel compared to clopidogrel were compared in the PLATO and TRILOGY trials respectively: In the former, ticagrelor was superior to clopidogrel, while in the latter, prasugrel was not shown to be superior to clopidogrel. Based on these studies, we recommend ticagrelor instead of clopidogrel. For patients in whom ticagrelor cannot be used, we suggest using clopidogrel instead of prasugrel. This preference is based on its lower cost, a greater experience with its use, and a trend toward higher rates of bleeding in TRILOGY. Major bleeding is an important concern with the use of P2Y12 receptor blockers. The following two points should be kept in mind when choosing between ticagrelor, prasugrel, and clopidogrel: Specific relative contraindications to full dose (10 mg daily) prasugrel include patients age 75 years or older or weight less than 60 kg, although the 5 mg daily dose appears to be safe in this patient population. Prasugrel is absolutely contraindicated in patients with past stroke or transient ischemic attack. Ticagrelor was not associated with an increased risk of bleeding in patients with prior stroke or TIA, but relatively few patients in the randomized trial (4 percent of the total enrolled) met this criterion and thus experience is limited; clopidogrel 300 mg is preferred in these patients. For patients otherwise at high risk for bleeding due to prior hemorrhagic stroke, ongoing bleeding, bleeding diathesis, or clinically

relevant anemia or thrombocytopenia, clopidogrel 300 mg is preferred in most cases. RESISTANCE/NONRESPONSE TO ASPIRIN OR CLOPIDOGREL The subject of resistance/nonresponse to aspirin or clopidogrel, along with methods to determine in vitro platelet function following treatment with clopidogrel, are discussed separately. (See "Clopidogrel resistance and clopidogrel treatment failure".) GP IIb/IIIa INHIBITORS Potent inhibition of platelet aggregation in patients with a non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome (ACS) can be achieved by the use of intravenous glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa inhibitors, which inhibit the final common pathway of platelet aggregation, the crossbridging of platelets secondary to fibrinogen binding to the activated GP IIb/IIIa receptor. The addition of GP IIb/IIIa improves outcomes in some patients with non-ST elevation ACS. (See "Platelet biology", section on 'Platelet activation'.) Evidence from early trials The early randomized trials of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors are presented separately (see "Early trials of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors in coronary heart disease"). The following conclusions are of limited applicability to patients treated today with the routine use of P2Y12 receptor blockers and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stenting: In trials of patients treated with medical therapy: abciximab did not improve outcomes; tirofiban was of benefit in patients in troponin positive patients; and eptifibatide improved outcomes [54-58]. In trials of intervention with balloon angioplasty, outcomes were better with abciximab, tirofiban, or eptifibatide (compared to placebo) [54,57,59]. Among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting, benefit has been demonstrated with eptifibatide and tirofiban [60,61]. A 2002 meta-analysis examined individual data from six randomized trials

of 31,400 non-ST elevation ACS patients treated with aspirin and heparin who did not undergo early (<48 hours) revascularization [62]. GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor use was associated with a significant reduction in the combined end point (death or MI) at five days (5.7 versus 6.9 percent for placebo/control, odds ratio [OR] 0.84, 95 percent CI 0.77 to 0.93) and at 30 days (10.8 versus 11.8 percent, OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.85-0.98). Benefit appeared to be limited to the highest risk patients. Evidence from recent trials The above meta-analysis was published before the current upstream use of platelet P2Y12 receptor blockers in most or bivalirudin as the anticoagulant in some patients with non-ST elevation ACS. In the ISAR-REACT 2 trial, 2022 patients with a non-ST elevation ACS undergoing PCI with stenting were treated with clopidogrel (600 mg loading dose at least two hours before PCI) and then randomly assigned to abciximab or placebo in the catheterization laboratory [63]. All patients received heparin as the anticoagulant. The following findings were noted: Abciximab therapy was associated with a significant reduction in the rate of the primary end point of death, myocardial infarction (MI), or urgent target vessel revascularization at 30 days (8.9 versus 11.9 percent; relative risk [RR] 0.75, 95% CI 0.58-0.97). The lower rate was driven principally by a lower rate of myocardial infarction. Among patients without an elevated troponin level (about half of the study population), there was no difference in the incidence of primary end point events between the two groups (4.6 percent in both groups; relative risk 0.99, 95% CI 0.56-1.76). Among patients with an elevated troponin, the incidence of events was significantly lower in the abciximab group (13.1 versus 18.3 percent; RR of 0.71, 95% CI 0.54-0.95). There were no significant differences in the two groups in the risk of major bleeding. In the ISAR-REACT 4 trial, which compared bivalirudin to heparin plus GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor in non-ST elevation MI patients receiving aspirin and

clopidogrel, the rate of death, recurrent MI, or urgent target-vessel revascularization was similar between the two groups, but bleeding occurred significantly more often in those receiving heparin plus glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor [64]. This trial is discussed in detail elsewhere. (See "Anticoagulant therapy in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes", section on 'Bivalirudin'.) Special considerations Timing The optimal time of initiation of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor therapy in patients with an NSTEMI who are treated with an early invasive strategy was addressed in the ACUITY Timing and EARLY ACS trials; ACUITY Timing was a sub-randomization of the ACUITY trial of moderate- to highrisk ACS patients. (See "Antithrombotic therapy for intracoronary stent implantation: Clinical trials", section on 'Bivalirudin'.) In the ACUITY Timing trial, 9207 non-ST elevation ACS patients scheduled to undergo an invasive strategy were randomly assigned to either upstream GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor (eptifibatide or tirofiban) or deferred GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor [65].The primary outcome was assessment of noninferiority of deferred GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor use compared with upstream administration for the prevention of composite ischemic events. The following findings were noted at 30 days: The composite primary end point of death, MI, or unplanned revascularization occurred more often in patients in the deferred group (7.9 versus 7.1 percent; relative risk 1.12, 95% CI 0.97-1.29) and therefore the criteria for non-inferiority for deferred therapy were not met. The excess risk with deferred GP IIb/IIIa consisted entirely of an increase rate of unplanned revascularizations, however, not death or myocardial infarction. Deferred use resulted in significantly reduced 30 day rates of major bleeding (4.9 versus 6.1 percent). The lower rate of bleeding with deferred therapy probably reflects selective use. With deferred therapy, a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor would only be given to those undergoing PCI, while all patients would be treated with upstream therapy. In EARLY ACS, 9492 non-ST elevation high-risk ACS patients scheduled to undergo an invasive strategy were randomly assigned to either early

(after randomization) eptifibatide or placebo with provisional use of eptifibatide after angiography (delayed) [66]. High risk was defined as meeting two or more of the following criteria: ischemic changes on electrocardiography, a level of troponin or creatine kinase MB that was above the upper limit of normal, and an age of 60 years or greater. Early aspirin use (initial dose of 162 to 325 mg orally) was mandated; early clopidogrel use was encouraged but not mandated. Antithrombin therapy was used in over 94 percent of patients. The early use of eptifibatide was associated with the following findings: There was no significant reduction in the rate of the primary composite outcome of death from any cause, myocardial infarction, recurrent ischemia requiring urgent revascularization, or thrombotic bailout at 96 hours (9.3 versus 10.0 percent; odds ratio [OR] 0.92, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.06). The likelihood of TIMI major hemorrhage was significantly increased (2.6 versus 1.8 percent; OR 0.015, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.89). These two large trials, of similar but not identical design, did not demonstrate a significant benefit of early compared with delayed use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, even in high-risk patients with non-STEMI ACS who are scheduled to undergo early PCI. The early use of GP IIb/IIIa use was associated with a significantly increased risk of bleeding. (See 'Bleeding risk' above.) Dosing Abciximab, eptifibatide, and tirofiban have been evaluated in patients with non-ST elevation ACS. We prefer eptifibatide for patients in whom GP IIb/IIIa receptor blocker will be started before PCI. For patients who will undergo PCI in the catheterization laboratory, we prefer either abciximab or eptifibatide. The basis for these preferences are that abciximab use prior to coronary angiography has not been sufficiently evaluated and the optimal dosing regimen for tirofiban is less clearly defined than for either abciximab or eptifibatide. The dosing regimens for the first two drugs are generally agreed upon, but there is uncertainty concerning the optimal dosing regimen for tirofiban in non-ST elevation ACS patients. It should be kept in mind that each drug has not been tested in all possible clinical scenarios, such as risk level or timing of PCI. The recommendations that follow are based on dosing

regimens used in clinical trials: AbciximabA bolus of 0.25 mg/kg should be followed by a continuous infusion of 0.125 mcg/kg/min (maximum: 10 mcg/min), which is continued for 12 hours. As most of the trials that tested abciximab started the drug in the catheterization laboratory or soon before, we recommend that it not be used in patients in whom catheterization is delayed for more than four hours. EptifibatideA loading dose of 180 mcg/kg (maximum: 22.6 mg) over one to two minutes should be followed by a continuous infusion of 2 mcg/kg/min (maximum: 15 mg/hour), which is continued for 18 to 24 hours. A second 180-mcg/kg bolus should be given 10 minutes after the first bolus. The continuous infusion should be reduced by 50 percent in patients with estimated creatinine clearance <50 mL/min. TirofibanA loading dose of 25 mcg/kg (referred to as the high-bolus dose) over three minutes, which should be followed by a continuous infusion of 0.15 mcg/kg/min, which is continued for 18 to 24 hours. This dosing is not in United States (US) licensed product information (the US approved dose is 0.4 mcg/kg/min over 30 minutes and infusion of 0.1 mcg/kg/min). This higher dose of tirofiban has shown benefit in small studies [67,68] and is in the licensed product information for the United Kingdom and some European countries, but has not been validated in large clinical trials. We are concerned that any lower dose will not achieve adequate GP IIb/IIIa receptor blocked if given soon before PCI. The optimal dose for patients not undergoing PCI within four hours is unknown, but the US approved dose may achieve adequate platelet inhibition [55,56,69]. If tirofiban is chosen, we suggest that the infusion dose reduced by 50 percent in patients with an estimated creatinine clearance of <30 mL/min. Serum troponins An interesting observation from the PRISM, CAPTURE, and PARAGON B trials and a meta-analysis is that the benefit from GP IIb/IIIa inhibition primarily occurred in the subset of patients who had elevations in troponin T and/or I [62,70-72]. In PRISM, this benefit was

seen whether patients were managed medically or with revascularization (figure 7) [70]. The same pattern of benefit limited to patients with elevated troponins was also noted in the ISAR-REACT 2 trial of patients also treated with clopidogrel [63]. (See 'Evidence from recent trials' above.) Increases in serum troponin T and I are considered to be a surrogate marker for thrombus formation, since they are associated with complex lesion characteristics and visible thrombus [73]. Such patients may be most likely to benefit from a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor. Combined use with enoxaparin Although most of the trials have evaluated the safety and efficacy of the GP IIb/IIIa agents in patients receiving unfractionated heparin, these drugs are also safe and of benefit when used with enoxaparin, a low molecular weight heparin. Enoxaparin may be associated with improved outcomes compared to unfractionated heparin, particularly in high-risk patients. (See "Anticoagulant therapy in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes", section on 'Enoxaparin versus UFH'.) Patients selected for CABG We agree with the recommendation made in the 2011 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association guideline CABG which states that eptifibatide or tirofiban should be discontinued for at least two to four hours before surgery and that abciximab for at least 12 hours [74]. These time intervals are derived from pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling of the return of platelet function. Bleeding risk Major bleeding can occur after the administration of a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor as a consequence of inhibition of platelet function or thrombocytopenia. The mechanism and frequency of thrombocytopenia, as well as recommendations for measurement of platelet count, are discussed separately. (See "Thrombocytopenia induced by glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors".) In randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials of the GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors, abciximab had a 0 to 7 percent excess risk of major bleeding compared to placebo, while tirofiban and eptifibatide had a 0 to 2 percent excess risk. (See "Early trials of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors in coronary heart disease".) However, most of these trials were completed before the stent era in which the administration of both aspirin and clopidogrel has become routine. Data on the rates of major bleeding in patients with non-ST elevation ACS treated with aspirin and clopidogrel are available from the ISAR-REACT 2 trial and the CRUSADE initiative:

In ISAR-REACT 2, all patients received pretreatment with aspirin and 600 mg of clopidogrel [63]. The rates of major bleeding for patients receiving abciximab or placebo were not significantly different (4.5 and 4.0, respectively). In an analysis of 32,600 patients with a non-ST elevation ACS in the CRUSADE initiative, the rate of major bleeding, defined as a drop in hematocrit of 12 percent, need for transfusion, or intracranial hemorrhage, was significantly higher in patients who received GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors (10.1 versus 6.8 percent) [75]. Some of this increase in risk may have been due to clopidogrel, since the rate of clopidogrel use was higher in the patients treated with a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor (63 versus 39 percent in those who did not receive a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor). Two groups of patients at particularly high risk for GP IIb/IIIa-induced major bleeding are those with moderate to severe renal insufficiency [76,77] and women [75]. Although elderly patients are at increased risk of bleeding after PCI, the risk of bleeding requiring transfusion or major bleeding does not appear to be influenced by whether or not a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor is given [78]. Summary Based upon the evidence cited above, GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor therapy is warranted in some ACS patients treated with PCI, particularly those not treated with bivalirudin anticoagulation. For these patients, who are usually treated with unfractionated heparin, GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor use should be deferred until after diagnostic angiography in most patients to decrease the risk of bleeding. Based primarily on the results of the ISAR-REACT 2 trial discussed above, we make the following recommendations for ACS patients scheduled for PCI in whom heparin is chosen as the anticoagulant: For troponin positive patients, we suggest adding a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor. The evidence to do so is of higher quality if clopidogrel is the P2Y12 receptor blocker, and of lower quality if ticagrelor or prasugrel is chosen.

For troponin negative patients, we recommend not adding GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor. As we prefer bivalirudin (either as the first anticoagulant or after a switch from heparin) to heparin in patients with non-ST elevation ACS undergoing PCI, we recommend not routinely adding a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor in this setting. (see "Anticoagulant therapy in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes", section on 'Summary and recommendations'). The ISARREACT 4 trial found no significant evidence of benefit and the bleeding rate was higher with GP IIb/IIIa use. For patients treated with either bivalirudin or a heparin and evidence of ongoing ischemia, the addition of GP IIb/III inhibitor prior to diagnostic angiography is reasonable. This recommendation applies to patients who have received a P2Y12 inhibitor and to patients in whom a decision has been made to withhold P2Y12 inhibitor until diagnostic angiography. While there is evidence to recommend GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor therapy in highrisk patients treated with a conservative approach, the evidence comes from studies performed before the routine use of P2Y12 receptor blockers. Thus, we suggest not adding a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor for these high-risk patients on dual oral antiplatelet therapy, unless there is evidence of recurrent ischemia. PAR-1 ANTAGONISTS Protease-activated-receptor 1 (PAR-1) antagonists inhibit thrombin induced platelet activation. (See "Overview of hemostasis", section on 'Thrombin'.) In the TRACER trial, nearly 13,000 patients with an acute coronary syndrome (more than 90 percent had a non-ST elevation MI) were randomly assigned to vorapaxar, an oral PAR-1 antagonist, or placebo in addition to aspirin and a platelet P2Y12 receptor blocker [79]. The trial was stopped early due to an increase in bleeding with vorapaxar, although the targeted number of end points had been achieved by conclusion of the trial. Voraxapar did not significantly reduce the primary composite ischemic end point in TRACER, but major bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage rates were substantially increased. PATIENTS TAKING ORAL ANTICOAGULANTS Some patients with acute coronary syndromes are receiving oral anticoagulant therapy at the time of the event. This issue is discussed in detail elsewhere. (See "Triple antithrombotic therapy in patients with cardiovascular disease".) RECOMMENDATIONS OF OTHERS Guidelines from American

College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (2007 and revised in 2012) [53,80], the European Society of Cardiology (2011) [52], and the American College of Chest Physicians (2012) [81] have included recommendations for the use of antiplatelet agents in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Our recommendations below are generally consistent with recommendations found in these guidelines. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS Our recommendations for the use of antiplatelet therapy in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes (ACS) follow. Additional recommendations for the long-term use of these drugs are found elsewhere. (See "Antiplatelet therapy after coronary artery stenting", section on 'Long-term antiplatelet therapy' and "Benefits and risks of aspirin in secondary and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease", section on 'Secondary prevention'.) An early step in the treatment of patients with non-ST elevation ACS is choice between choosing an invasive or a conservation strategy. This issue is discussed in detail elsewhere. (See "Coronary arteriography and revascularization for unstable angina or non-ST elevation acute myocardial infarction", section on 'Summary and recommendations'.) The following comments regarding antiplatelet therapy apply irrespective of whether an invasive or a conservative approach is chosen: For all patients with non-ST elevation ACS, we recommend dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and a platelet P2Y12 receptor blocker, as opposed to single antiplatelet therapy (Grade 1B). (See 'Summary' above.) We recommend aspirin and a platelet P2Y12 receptor blocker for a minimum of one year (Grade 1B). (See 'Duration of therapy' above.) We recommend that aspirin be given immediately (at the time of diagnosis) (Grade 1A). (See 'Dose' above.) The first aspirin tablet should be chewed and contain 162 to 325 mg. At discharge, the dose of aspirin should be 75 to 100 mg daily; if ticagrelor is chosen as the platelet P2Y12 receptor blocker, the discharge dose of aspirin should not be greater than 100 mg daily. With regard to P2Y12 receptor blockers: The loading dose for ticagrelor is 180 mg, for prasugrel 60 mg,

and for clopidogrel 300 to 600 mg (600 mg is preferred for patients undergoing an invasive strategy). (See 'Timing' above.) In deciding between one P2Y12 receptor blocker and another, the risk of bleeding needs to be taken into account. (See 'Bleeding risk' above.) In addition, cost or availability may enter into decision making. For those patients with a history of gastrointestinal bleeding, drugs that reduce the risk of recurrent bleeding (eg, proton pump inhibitors) should be given. (See "Overview of the acute management of unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction".) Invasive approach For patients scheduled for an invasive approach, we suggest that P2Y12 receptor blocker therapy be given at the time of diagnosis rather than after coronary angiography (Grade 2B). (See 'Timing' above.) For patients scheduled for an invasive approach and in whom a P2Y12 receptor blocker will be withheld until the coronary anatomy is known, we recommend either ticagrelor or prasugrel as opposed to clopidogrel (Grade 1A). Issues such as cost and local preference may reasonably influence the choice between the two. (See 'Summary' above.) For patients who are managed with an invasive approach and who will receive P2Y12 receptor blocker prior to diagnostic angiography, we recommend ticagrelor instead of clopidogrel (Grade 1A). We suggest not giving prasugrel in these patients (Grade 2B). If prasugrel is chosen before diagnostic angiography, it should be given only to patients at low risk of bleeding. (See 'Summary' above and 'Bleeding risk' above.)

We prefer bivalirudin to heparin (anticoagulant therapy) in patients with non-ST elevation ACS undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). (See 'Summary' above.) For patients in whom bivalirudin will be used as the anticoagulant, either after a switch from heparin or as the initial anticoagulant, we recommend not adding GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor to the antiplatelet regimen (Grade 1B). For troponin positive patients in whom heparin is chosen as the anticoagulant and clopidogrel is chosen as the P2Y12 receptor blocker, we suggest addition of a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor (Grade 2B). For these patients treated with heparin in whom either ticagrelor or prasugrel is chosen as the P2Y12 receptor blocker, we suggest addition of a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor (Grade 2C). In most patients the GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor should be started after diagnostic angiography. (See 'GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors' above and 'Clopidogrel' above.) For very high-risk patients (eg, markedly elevated troponin, recurrent ischemic discomfort, dynamic electrocardiographic changes, or hemodynamic instability) undergoing an invasive approach, we suggest the early (before angiography) addition of a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor (Grade 2C). (See 'Evidence from recent trials' above.) For patients in whom GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor will be started before angiography, we suggest eptifibatide in preference to abciximab or tirofiban (Grade 2B). For patients in whom GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor will be started after diagnostic angiography, we suggest abciximab or eptifibatide in preference to tirofiban (Grade 2C). Cost and local practice may influence the choice of agent. (See 'Dosing' above and "Antithrombotic therapy for percutaneous coronary intervention: General use".) Conservative approach For those patients managed without an invasive approach (conservative approach), we recommend ticagrelor rather than clopidogrel (Grade 1B). (See 'Summary' above.) For such patients who cannot receive ticagrelor, we suggest clopidogrel rather than prasugrel (Grade 2C). For very high-risk patients (eg, elevated troponin, recurrent ischemic

discomfort, dynamic electrocardiographic changes, or hemodynamic instability) who will be managed with a conservative approach, we suggest adding a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor (Grade 2C). (See 'Summary' above.) For these patients, we suggest eptifibatide or tirofiban instead of abciximab (Grade 2C). The GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor infusion should be initiated at presentation and continued for 48 to 72 hours. Dose adjustment may be necessary in the presence of chronic kidney disease. Use of UpToDate is subject to the Subscription and License Agreement.

You might also like

- Stroke Topic DiscussionDocument19 pagesStroke Topic Discussionapi-648714317No ratings yet

- AntiplateletDocument2 pagesAntiplateletdewsNo ratings yet

- Acute Coronary Syndrome Oral Anticoagulation in Medically Treated Patients - UpToDateDocument14 pagesAcute Coronary Syndrome Oral Anticoagulation in Medically Treated Patients - UpToDateBrian VianaNo ratings yet

- High-Dose Clopidogrel, Prasugrel or Ticagrelor: Trying To Unravel A Skein Into A Ball. Alessandro Aprile, Raffaella Marzullo, Giuseppe Biondi Zoccai, Maria Grazia ModenaDocument8 pagesHigh-Dose Clopidogrel, Prasugrel or Ticagrelor: Trying To Unravel A Skein Into A Ball. Alessandro Aprile, Raffaella Marzullo, Giuseppe Biondi Zoccai, Maria Grazia ModenaDrugs & Therapy StudiesNo ratings yet

- Antiplatelet Therapy For The Secondary Prevention of Ischemic Stroke - UpToDateDocument13 pagesAntiplatelet Therapy For The Secondary Prevention of Ischemic Stroke - UpToDateSuci WijayaNo ratings yet

- Aspirin Plavix and Other Antiplatelet Medicat - 2016 - Oral and MaxillofacialDocument10 pagesAspirin Plavix and Other Antiplatelet Medicat - 2016 - Oral and MaxillofacialjoseluisNo ratings yet

- CPG3 Secondary Stroke PreventionDocument10 pagesCPG3 Secondary Stroke Preventionmochamad rizaNo ratings yet

- Merec Bulletin Vol15 No6Document4 pagesMerec Bulletin Vol15 No6n4dn4dNo ratings yet

- CYP450 System and Not BeingDocument5 pagesCYP450 System and Not BeingArfa'i LaksamanaNo ratings yet

- Br. J. Anaesth. 2007 Chassot 316 28Document13 pagesBr. J. Anaesth. 2007 Chassot 316 28Rhahima SyafrilNo ratings yet

- CLOPIDOGRELDocument4 pagesCLOPIDOGRELHuseikha VelayazulfahdNo ratings yet

- Aspirin Kod KVBDocument7 pagesAspirin Kod KVBLukaNo ratings yet

- Anticoagulation and Antiplatelet Therapy in Acute Coronary Syndromes (CCJM 2014)Document12 pagesAnticoagulation and Antiplatelet Therapy in Acute Coronary Syndromes (CCJM 2014)Luis Gerardo Alcalá GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Antithrombotic Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack - UpToDateDocument24 pagesAntithrombotic Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack - UpToDateFerasNo ratings yet

- Angina Pectoris Treatment & Management - Medical Care, Surgical Care, PreventionDocument20 pagesAngina Pectoris Treatment & Management - Medical Care, Surgical Care, Preventionblack_eagel100% (1)

- Acute non-ST-elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: Early Antiplatelet Therapy (UPTODATE)Document27 pagesAcute non-ST-elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: Early Antiplatelet Therapy (UPTODATE)kabulkabulovich5No ratings yet

- DR Huma NstemiDocument114 pagesDR Huma NstemiArzalan BaigNo ratings yet

- Combining Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Therapy in Cardiovascular Disease - 2020 - AHADocument7 pagesCombining Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Therapy in Cardiovascular Disease - 2020 - AHADrHellenNo ratings yet

- Early Antithrombotic Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack - UpToDateDocument27 pagesEarly Antithrombotic Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack - UpToDateEduardo QuinteroNo ratings yet

- Update On Anti Platelet TherapyDocument4 pagesUpdate On Anti Platelet TherapyhadilkNo ratings yet

- MinaDocument6 pagesMinaminamoharebNo ratings yet

- Antiplatelet Agents For Stroke PreventionDocument13 pagesAntiplatelet Agents For Stroke PreventionYanthie Moe MunkNo ratings yet

- Aspirin, Plavix, and Other Antiplatelet Medications What The Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon Needs To KnowDocument10 pagesAspirin, Plavix, and Other Antiplatelet Medications What The Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon Needs To KnowLaura Giraldo QuinteroNo ratings yet

- Anti Platelets Agents: Dr. Sachana KC 1 Year Resident Department of AnesthesiaDocument61 pagesAnti Platelets Agents: Dr. Sachana KC 1 Year Resident Department of AnesthesiaKshitizma GiriNo ratings yet

- JCN 10 189 PDFDocument8 pagesJCN 10 189 PDFMeilinda SihiteNo ratings yet

- Nejmoa 010746Document9 pagesNejmoa 010746Mmle BlaséNo ratings yet

- Why Do Some Low-Dose Aspirin Formulations Intended For Use As Anti-Platelet Medications Contain Glycine?Document10 pagesWhy Do Some Low-Dose Aspirin Formulations Intended For Use As Anti-Platelet Medications Contain Glycine?Hueysha KhorNo ratings yet

- Aspirin, Clopidogrel, and Ticagrelor in Acute Coronary SyndromesDocument9 pagesAspirin, Clopidogrel, and Ticagrelor in Acute Coronary SyndromesJicko Street HooligansNo ratings yet

- Antiplatelet Therapy: New Antiplatelet Drugs in PerspectiveDocument4 pagesAntiplatelet Therapy: New Antiplatelet Drugs in Perspectivegeo_mmsNo ratings yet

- TIM StudyDocument9 pagesTIM StudypsoluopostimNo ratings yet

- Ticagrelor PDFDocument7 pagesTicagrelor PDFNurul Masyithah100% (1)

- 19 - 30Document11 pages19 - 30Tasya IrwanNo ratings yet

- Review of Medical Treatment of Stable Ischemic Heart DiseaseDocument11 pagesReview of Medical Treatment of Stable Ischemic Heart DiseaseSuci NourmalizaNo ratings yet

- Antiplatelet Treatment in Stable Coronary Artery DiseaseDocument6 pagesAntiplatelet Treatment in Stable Coronary Artery DiseaserambutsapukusayangNo ratings yet

- Significant Early In-Hospital Benefit Was Seen. Clopidogrel Is Prefferd ToDocument8 pagesSignificant Early In-Hospital Benefit Was Seen. Clopidogrel Is Prefferd TogilnifNo ratings yet

- Su 2015Document7 pagesSu 2015carolin enjelin rumaikewiNo ratings yet

- Anticoagulation Module 2Document13 pagesAnticoagulation Module 2angelmedurNo ratings yet

- Contraindications To Thrombolytic Therapy: Aminocaproic AcidDocument3 pagesContraindications To Thrombolytic Therapy: Aminocaproic AcidTia Siti RoilaNo ratings yet

- Diener 2007Document7 pagesDiener 2007Pranav PatelNo ratings yet

- Aspirin Resistance: Is It Real and Does It Matter?: DR - Wai-Hong ChenDocument3 pagesAspirin Resistance: Is It Real and Does It Matter?: DR - Wai-Hong ChenPepo AryabarjaNo ratings yet

- Document PDFDocument12 pagesDocument PDFnikenauliaputriNo ratings yet

- Antiplatelet Regimens in The Long-Term Secondary Prevention of Transient Ischaemic Attack and Ischaemic Stroke: An Updated Network Meta-AnalysisDocument28 pagesAntiplatelet Regimens in The Long-Term Secondary Prevention of Transient Ischaemic Attack and Ischaemic Stroke: An Updated Network Meta-Analysisnurafriani2No ratings yet

- Aspirina Riesgos y Beneficios - Clev Clin J Med 2013Document9 pagesAspirina Riesgos y Beneficios - Clev Clin J Med 2013Ari JimenezNo ratings yet

- Stroke Prevention: Multimedia Library ReferencesDocument17 pagesStroke Prevention: Multimedia Library Referencesmochamad rizaNo ratings yet

- Genetic Implications Pregnancy CategoryDocument4 pagesGenetic Implications Pregnancy CategoryElizabeth LevitskyNo ratings yet

- Stemi Vs NstemiDocument31 pagesStemi Vs NstemiFadhilAfifNo ratings yet

- Aspirin Resistance in Cardiovascular Disease A ReviewDocument10 pagesAspirin Resistance in Cardiovascular Disease A ReviewVioleta GrigorasNo ratings yet

- Articulo - FarmacologíaDocument13 pagesArticulo - FarmacologíaJhon RVNo ratings yet

- ACS Management at The Emergency Department (Ali Haedar)Document38 pagesACS Management at The Emergency Department (Ali Haedar)Endar EszterNo ratings yet

- DAPA-HF Full PublicationDocument13 pagesDAPA-HF Full PublicationPutra AchmadNo ratings yet

- Antiplatelet Agents in Acute ST Elevation Myocardial InfarctionDocument12 pagesAntiplatelet Agents in Acute ST Elevation Myocardial InfarctionteranrobleswaltergabrielNo ratings yet

- CURE TrialDocument9 pagesCURE TrialCristina PazmiñoNo ratings yet

- Pegasus TIMI 54 TrialDocument13 pagesPegasus TIMI 54 TrialIsaac Aaron Enriquez MonsalvoNo ratings yet

- Evidencia Clinica de Antiagregantes Plaquetarios y Ima 2015Document11 pagesEvidencia Clinica de Antiagregantes Plaquetarios y Ima 2015Edgar PazNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Atherotrobmotic EventsDocument14 pagesPrevention of Atherotrobmotic Eventsddandan_2No ratings yet

- Sul 051Document6 pagesSul 051Trn Xu‰n Nhi�nNo ratings yet

- Acetylsalicyclic Acid 08july2022Document6 pagesAcetylsalicyclic Acid 08july2022Cuong LeNo ratings yet

- Acs 11 190524110746Document46 pagesAcs 11 190524110746Obakeng MandaNo ratings yet

- Australian PrescriberDocument3 pagesAustralian PrescriberMohamed OmerNo ratings yet

- Case 1 & 2Document4 pagesCase 1 & 2Adeel ShahidNo ratings yet

- Allopurinol Drug Study WWW RNpedia ComDocument9 pagesAllopurinol Drug Study WWW RNpedia ComifyNo ratings yet

- TCP HeartburnDocument12 pagesTCP HeartburnArlene NicomedezNo ratings yet

- CYP2C19 2, CYP2C19 3, CYP2C19 17 Allele and Genotype Frequencies in Clopidogrel-Treated Patients With Coronary Heart Disease in RussianDocument5 pagesCYP2C19 2, CYP2C19 3, CYP2C19 17 Allele and Genotype Frequencies in Clopidogrel-Treated Patients With Coronary Heart Disease in RussianSabrina JonesNo ratings yet

- Emergency Care SeminarDocument136 pagesEmergency Care SeminarSedaka DonaldsonNo ratings yet

- Kumpulan Daftar PustakaDocument8 pagesKumpulan Daftar PustakaAliyah Nia Fauziah DaudNo ratings yet

- ACCP Cardiology PRN JC June 2022Document16 pagesACCP Cardiology PRN JC June 2022topNo ratings yet

- Fibrinolytics, Anti Fibrinolytics and Anti Platelets: Dr. B.K.Bezbaruah Professor Pharmacology Gauhati Medical CollegeDocument46 pagesFibrinolytics, Anti Fibrinolytics and Anti Platelets: Dr. B.K.Bezbaruah Professor Pharmacology Gauhati Medical CollegeBidyut BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Chronic Limb IschemiaDocument27 pagesChronic Limb IschemiaGarima SahuNo ratings yet

- Clopidogrel and AspirinDocument12 pagesClopidogrel and AspirinNandan GuptaNo ratings yet

- Triple Antithrombotic Therapy For AF and Coronary StentsDocument7 pagesTriple Antithrombotic Therapy For AF and Coronary Stentsyesid urregoNo ratings yet

- Gastroproteccion Anticoagulacion y AntiagregaciónDocument13 pagesGastroproteccion Anticoagulacion y AntiagregaciónYesica Villalba CerqueraNo ratings yet

- Anaes Tutorial 1 - DR - MungrooDocument8 pagesAnaes Tutorial 1 - DR - MungrooChris DwarikaNo ratings yet

- Basics Arthroplasty ShrinandDocument420 pagesBasics Arthroplasty ShrinandPon Aravindhan A SNo ratings yet

- Surgical Foundations Sample Exam 2012Document34 pagesSurgical Foundations Sample Exam 2012Vy Nguyen100% (1)

- RLE Case PresentationDocument26 pagesRLE Case PresentationShaine BalverdeNo ratings yet

- DrugStudy SalutilloDocument5 pagesDrugStudy SalutilloErwin SmithNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary FinalDocument6 pagesExecutive Summary Finalapi-302265510No ratings yet

- ArticleDocument11 pagesArticleTry WirantoNo ratings yet

- Open Letter To FDA On Its Response To MRC's Citizen Petition RE The Vascepa SNDADocument56 pagesOpen Letter To FDA On Its Response To MRC's Citizen Petition RE The Vascepa SNDAMedical Research Collaborative, LLCNo ratings yet

- Medical Tribune May 2013Document39 pagesMedical Tribune May 2013Marissa WreksoatmodjoNo ratings yet

- A Brief Summary of Antiplatelet Agents - Deranged PhysiologyDocument3 pagesA Brief Summary of Antiplatelet Agents - Deranged Physiologyhnzzn2bymdNo ratings yet

- Ticlopidine (Ticlid™) and Clopidogrel (Plavix™)Document11 pagesTiclopidine (Ticlid™) and Clopidogrel (Plavix™)DhenokNo ratings yet

- SYROKE - Bare EssentialsDocument11 pagesSYROKE - Bare EssentialsPaula Vergara MenesesNo ratings yet

- 3rd International Congress On Neurology and Epidemiology: AbstractsDocument94 pages3rd International Congress On Neurology and Epidemiology: AbstractsKanchanaKesavanNo ratings yet