Professional Documents

Culture Documents

West. Oriental in Archiloch.

West. Oriental in Archiloch.

Uploaded by

Ro OrCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

West. Oriental in Archiloch.

West. Oriental in Archiloch.

Uploaded by

Ro OrCopyright:

Available Formats

MARTIN L.

WEST S OM E O RI E NT AL M OT I FS

IN

A RCHI L OCHUS

aus: Zeitschrift fr Papyrologie und Epigraphik 102 (1994) 15

Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn

SOME ORIENTAL MOTIFS IN ARCHILOCHUS

The influence on early Greek poetry of oriental - and more especially Semitic - literary forms and techniques, motifs, and idioms becomes ever more clearly a fact to be reckoned with.1 The Cologne Epode revealed Archilochus using a proverb that was current more than a thousand years earlier in Sumerian and Akkadian: 'the bitch in her haste gave birth to blind puppies'. 2 There is in fact another in an iambic fragment published twenty years previously.3 Such items of popular wisdom must have spread all over the Near East and into the Aegean, and it is natural that they should surface in a poet such as Archilochus, who draws freely on popular turns of speech. The same applies, at a somewhat more formal level, to his use of animal fables, an originally Near Eastern genre. The close similarity of his fable of the fox and the eagle to the story incorporated in the Old Babylonian poem Etana has been noted by several scholars.4 The iambos was an ancient institution which, to judge by its non-Greek name, had its roots in the pre-Hellenic culture of the Aegean. Both this historical background and the popular nature of the festivity with which the iambos was associated are conditions favourable to the sporadic appearance of motifs that link up with the Near East.5 From an early period Mesopotamia and lands influenced by Mesopotamian culture knew a type of entertainer not altogether unlike the performer of some kinds of iambos and similar figures such as the deikhli!t! and atokbdalo!: the aluzinnu.6 He has been described as 'a buffoon who made a living entertaining others with parodies, mimicry, and scatological songs'.7 In lexical lists the aluzinnu appears in immediate association with

1 I am preparing a large and shocking book on the subject. 2 Archil fr. 196a. 39-41 W. 2 ; letter of Shamshi-Adad in G.Dossin, Archives Royales de Mari I, Paris 1950,

no. 5. 11-13; W.Burkert, The Orientalizing Revolution, Cambridge (Mass.) 1992, 122; latest translation in B.R.Foster, Before the Muses. An Anthology of Akkadian Litereture, Bethesda (Maryland) 1993, 349. The proverb is also attested in Arabic, Turkish, et al.; for references to the growing secondary literature on it see W.W.Hallo in T.Abusch et al. (ed.), Lingering Over Words. Studies in Ancient Near Eastern Literature in honor of William L.Moran, Atlanta 1990, 208. 3 Fr. 23. 15f., 'I know how to hate my enemy and be the ant that [ ]s him': cf. C.Bezold, The Tell elAmarna Tablets in the British Museum, London 1892,61 (translation in Foster 350), 'When an ant is struck, does it not fight back and bite the hand of the man that strikes it?' 4 See now Burkert 121 f. The opening of the fox's prayer to Zeus, Ze, pter Ze, !n mn orano krto!, sounds like a Jewish prayer; cf. David's prayer in 1 Chron. 29. 11, 'Thine, O Lord, is the greatness and the power ... for all in the heavens and in the earth is thine...' 5 It is hardly relevant that one of the iambographers, Ananios or Ananias, has a West Semitic name, corresponding either to the common Hnanyah/Hnanyh (Jer. 28. 1 etc.), 'Yah(u) is gracious', or to nanyah (Neh. 3.23), 'servant of Yah'. 6 See B.R.Foster, JANES (Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society of Columbia University) 6, 1974, 74-9; W.H.P.Rmer, Persica 7, 1975-8, 43-68. 7 Foster, art.cit. 74.

M.L.West

words meaning 'slanderer', 'farter', and 'shitter'. One of his characteristics is that he is absurdly boastful. He recounts ridiculous adventures in which he has been involved; he makes fun of dignified persons such as the aipu (incantation-priest) by impersonating them and producing preposterous ritual prescriptions;8 there is possible evidence for female impersonation too.9 He may originally have had some cult connection, as in the Ur III period (late third millennium) he is listed among temple personnel. In the early second millennium there is a record of an aluzinnu performing at wedding festivities in Alalakh, within 50 km. of the Mediterranean.10 Similar Bronze Age popular entertainments in the Aegean area may have formed the background out of which the iambos and its congeners evolved. A conspicuous feature of the Ionian iambos is the uninhibited description of sexual activities involving promiscuous young women. There can be no doubt that originally, at any rate, this bawdy element was ritually determined, and connected with the promotion of fertility.11 In Archilochus the promiscuous women are the daughters of Lykambes. We have a series of trimeter fragments which are naturally taken to refer to the willing participation of one or other or both of them in sexual activities, described in graphic detail.12 Two fragments (39, 45) suggest the presence of several males, and elsewhere (frr. 207-8) Neoboule was called dmo! and rgti!, terms implying prostitution. Sex is a universal, and its possibilities finite. Yet several of the fragments in question have parallels in oriental material that seem to go beyond the casual and fortuitous. In fr. 42 once of the girls is described in action in these terms: !per ali brton Yrj nr Frj muze: kbda d n poneomnh. The meaning is almost certainly that she is performing fellatio, described with the graphic simile of the Thracian or Phrygian drinking beer through a tube, and at the same time being penetrated from behind. At various sites in Mesopotamia baked clay plaques have been found, dating from the Old Babylonian period, a thousand years or so before Archilochus, and showing a scene of sexual intercourse with the man entering the woman from behind while she is bending forward and at the same time drinking through a tube from a jar that

8 We recall that the Spartan deikhli!t! might impersonate a foreign doctor who used strange and

imposing language (Sosibios, FGrHist 595 F 7). Stephanie West makes the interesting suggestion that the word lazn may derive from aluzinnu or a related form; aluzinnu is a loan-word in Akkadian of unknown origin, the Sumerian equivalent being alam-zu. The conventional theory that lazn comes from the Thracian tribe called Alazne! or Alizne! is not very convincing. On the meaning of lazn cf. W.Burkert, Rh. Mus. 105, 1962, 51 n. 74. 9 Cf. the fragment of Semonides (16) where the speaker appears to be a prostitute. 10 Rmer 50 f. 11 Cf. the role of Iambe in the Demeter myth; my Studies in Greek Elegy and Iambus, Berlin & New York 1974, 23 ff. 12 Frr. 30 ff.; Studies in Greek Elegy and Iambus, 26 and 123-5.

Some Oriental Motifs in Archilochus

stands on the ground.13 The gap in time and space between these and Archilochus may seem problematic. But the same scene recurs on a cylinder seal from Cyprus, dated to the 14th or 13th century (here with a griffin watching the proceedings), and on four Persian seals of the Achaemenid period.14 Whether or not it originally had some ritual significance is unknown. It may be significant that one probable example comes from the temple of Ishtar at Assur. At any rate the strange scene enjoyed a wide diffusion in the ancient Near East, and it may be thought to have some relevance to the Archilochus fragment, even if the drinking through a tube is a literal act on the plaques and seals and only a simile in the Greek poet. In fr. 43 a man's penis in the act of ejaculating is compared to a donkey's: d o !yh . . . !t nou Prihnv! klvno! plmuren trughfgou. Here the parallel occurs in a most surprising place: in the fulminations of the prophet Ezekiel, 23. 19 f.: 'in the days of her youth, when she played the whore in the land of Egypt and was infatuated with her lovers there, whose members (lit. 'meat') were the members of asses and whose deluge (of semen) was the deluge of horses'.15 It is particularly remarkable that the context is a fantasy of two sisters (symbolizing Samaria and Jerusalem) who have abandoned themselves to lechery and grown old in it. Is it significant that Ezekiel wrote in Babylon and was palpably tinged with Babylonian culture? Has he based his allegory on some form of salacious popular literature or entertainment current in that country? The scandalous behaviour of Lykambes' daughters is located, among other settings, in the temenos of Hera.16 It is a fair guess that frr. 36 and 37 belonged together and referred to this temenos: pr! toxon klnyh!an n palin!kvi: toon gr aln rko! mfiddromen. The picture is of one or both girls lying down with one or more lovers in the shadow of the temenos wall. Then fr. 47 is addressed to someone whom 'the parynoi' drove away from the doors with sticks: perhaps virgin priestesses putting an end to the sacrilegious shenanigans.

13 R.Opificius, Das altbabylonische Terrakottarelief, Berlin 1961, 166-8, nos. 604-6, 608-9, 612-13, and p.

268 Taf. 20 no. 612; P.R.S.Moorey, Iraq 37, 1975, 91-2 and pl. xxv b, c; J.S.Cooper in the Reallexikon der Assyriologie IV, Berlin 1972-75, 262-3 and 266; H.W.F.Saggs, The Greatness that was Babylon, 2nd ed., London 1988, pl. 51c (after p. 362). I am indebted for these references to Dr Anthony Green of Wolfson College, Oxford. 14 E.Porada, AJA 52, 1948, 191-2 and pl. x no. 39; H.H. von der Otten, Art Bulletin 13, 1931, 224 fig. 14b; Cooper (as n. 13), 268. 15 t;m;dzI ysiWs jm'dzIw d;c;B] ydI/mt}Adc'B] dv,a} The Septuagint has a variant formulation: n ! nvn a !rke! atn ka adoa ppvn t adoa atn. 16 Dioscorides, Anth.Pal. 7.351.8 = 1562 Gow-Page Arxloxon m yeo! ka damona! ot n guia! edomen oy Hrh! n meglvi temnei.

M.L.West

Women who give themselves to a series of men on a goddess's holy ground make us think of oriental sacral prostitution. The suspicion is not that this existed in seventh-century Paros (Archilochus represents whoring on holy ground not as something institutionalized but as the most disgraceful impropriety), but rather that it is the underlying source from which the scene ultimately derives. 'The shadow of a wall' is in fact exactly the typical station of the Babylonian prostitute. In the Epic of Gilgamesh (VII 88 ff.) the dying Endiku lays a curse on the harlot Shamhat who seduced him from the wild and set him on the road to ruin; he is actually laying down the law for all future prostitutes: The crossroads shall be your sitting-place, the wasteland shall be your couch, the shadow of a wall shall be your standing-place. (105-7.) The last line recurs in a similar passage in the Descent of Ishtar (106), where Ereshkigal curses the rent-boy. Another example of this topos, but with the wall's shadow pictured in more agreeable terms, turns up in a remarkable text recently published by Wolfram von Soden: a tablet from Nippur which strengthens the link between Archilochean iambos and Babylonian sacral prostitution. It is the libretto of a song dating, according to the colophon, from the accession-year of Hammurapi (1848 BC, on the high chronology now in fashion), and perhaps indeed of Old Babylonian origin, though in its present linguistic form it has to be dated to the second half of the second millennium.17 It is complete in twenty lines. The first line is 'Rejoicing, that's a (sure) foundation for a (or the) city!', and all the other lines have this as a following refrain or response. Lines 2-7 are too fragmentary to translate, but they seem to contain references to Ishtar, to young men and a girl, and perhaps to a temple prostitute (kul[maitum?). Here is a fresh version of lines 8-20: One ca[me to her, and: (Refrain) 'Come, accept me!' (Refrain) Another too came to her and: (Refrain) 'Come, let me touch your "lintel"!' (Refrain) 'Well, as I am accepting you (pl.), (Refrain) gather me the young men of your city, (Refrain) and let's go to the shadow of the (or a) wall!' (Refrain) Seven to her waist, seven to her haunches, (Refrain) sixty and sixty find relief on her nakedness. (Refrain) The young men have wearied, (but) Ishtar is not wearied: (Refrain) 'Set to, young men, on my "lintel", such a nice one!' (Refrain)

17 W. von Soden, Orientalia N.S. 60, 1991, 339-42; Foster 590.

Some Oriental Motifs in Archilochus

When the girl spoke (thus), (Refrain) the young men heard, they accepted her word! (Refrain) The Akkadian word which I have rendered as 'lintel', urdatu, means (a) cross-beam, (b) the female sex organs, by a metaphor that recalls Archilochus' yr]igko d nerye ka pulvn (fr. 196a. 21). Besides this and the 'shadow of the wall', there are other details that recall Archilochus. The description of the crowd of young men all satisfying their lust may remind us of Archil. fr. 45, kcante! brin yrhn pflu!an. Other points to be noted are the enthusiasm and insatiability of the girl, who embodies the unfailing sexuality of Ishtar, and the festive tone of the song as a whole. One might take it for some sort of tavern song. But the colophon identifies it as a pa rum of Ishtar; parum is a rare term denoting some kind of song honouring a deity. Von Soden suggests that the tablet contains an excerpt from a temple ritual; 'der zwanzigmalige Refrain spricht fr ein vor einem greren Kreis vorgetragenes Kultlied.'18 If we wonder what such a song had to do with Ishtar, the most obvious answer is that she was the goddess of sexual love. But it is also worth noting that a Sumerian text associates her with knockabout humour: 'Streit Anfangen, Persiflieren, Gelchter, gering geachtet Sein (und) angesehen Sein, sind, Inanna/Etar, dein (Prrogativ).'19 A merry, bawdy song, performed in a cult setting, celebrating the fantastically insatiable young woman who wears out throngs of eager men in the shadow of the wall - have we here come upon some kind of distant, ancient relative of the Ionian iambos? All Souls College, Oxford M.L.West

18 Op. cit., 342. 19 Rmer 53.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Full Download Introduction To Quantum Mechanics 3rd Edition Griffiths Solutions ManualDocument35 pagesFull Download Introduction To Quantum Mechanics 3rd Edition Griffiths Solutions Manualfockochylaka83% (48)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Treasures of Darkness - A History of Mesopotamian Religion - Thorkild JacobsenDocument283 pagesThe Treasures of Darkness - A History of Mesopotamian Religion - Thorkild Jacobsenrupert1974100% (2)

- Archi, Alfonso Transmission of Recitative Literature by The HittitesDocument19 pagesArchi, Alfonso Transmission of Recitative Literature by The HittitesRo OrNo ratings yet

- Draupadi at The Walls of TroyDocument12 pagesDraupadi at The Walls of TroyRo OrNo ratings yet

- Leahy Amasis and ApriesDocument20 pagesLeahy Amasis and ApriesRo OrNo ratings yet

- Hoffner, Prayer of Muršili II About His StepmotheriDocument7 pagesHoffner, Prayer of Muršili II About His StepmotheriRo OrNo ratings yet

- Burkert, Walter. "Homerstudien Und OrientDocument28 pagesBurkert, Walter. "Homerstudien Und OrientRo OrNo ratings yet

- Penney The Etruscan Language in Its Italic Context, Etruscan by DefinitionDocument8 pagesPenney The Etruscan Language in Its Italic Context, Etruscan by DefinitionRo OrNo ratings yet

- Sacred Ritual: A Study of The West Semitic Ritual Calendars in Leviticus 23 and The Akkadian Text Emar 446Document288 pagesSacred Ritual: A Study of The West Semitic Ritual Calendars in Leviticus 23 and The Akkadian Text Emar 446Anıl Koca100% (1)

- Reichardt Linguistic Structures of Hittite and Luwian Curse Formulae, DissDocument196 pagesReichardt Linguistic Structures of Hittite and Luwian Curse Formulae, DissRo OrNo ratings yet

- Güterbock An Addition To The Prayer of Mursili, 1980Document11 pagesGüterbock An Addition To The Prayer of Mursili, 1980Ro OrNo ratings yet

- Ryholt. Nektaneb's DreamDocument6 pagesRyholt. Nektaneb's DreamRo OrNo ratings yet

- Hellenistic BactriaDocument24 pagesHellenistic BactriagiorgosbabalisNo ratings yet

- Niemeier Minoan Frescoes in The Eastern Mediterranean, 1998Document42 pagesNiemeier Minoan Frescoes in The Eastern Mediterranean, 1998Ro Or100% (2)

- Dillery. ManethoDocument26 pagesDillery. ManethoRo OrNo ratings yet

- Cook - Near - Eastern - Sources For Palace of AlcinoosDocument43 pagesCook - Near - Eastern - Sources For Palace of AlcinoosRo OrNo ratings yet

- Aruz The AEGEAN and The ORIENT The Evidence of The SealsDocument13 pagesAruz The AEGEAN and The ORIENT The Evidence of The SealsRo OrNo ratings yet

- 09 Hankey LeonardDocument11 pages09 Hankey LeonardRo OrNo ratings yet

- Boardman Greek Potters at Al-MinaDocument10 pagesBoardman Greek Potters at Al-MinaRo OrNo ratings yet

- Review of L.B. Van Der Meer Liber Linteus ZagrabiensisDocument6 pagesReview of L.B. Van Der Meer Liber Linteus ZagrabiensisRo OrNo ratings yet

- Bachvarova Suffixaufnahme and Genitival Adjectives As An Anatolian Areal Feature in Hurrian, Tyrrhenian and Anatolian Languages, 2007Document14 pagesBachvarova Suffixaufnahme and Genitival Adjectives As An Anatolian Areal Feature in Hurrian, Tyrrhenian and Anatolian Languages, 2007Ro OrNo ratings yet

- South East Asian Institute of Technology, Inc. National Highway, Crossing Rubber, Tupi, South CotabatoDocument25 pagesSouth East Asian Institute of Technology, Inc. National Highway, Crossing Rubber, Tupi, South CotabatoKristine Lagumbay GabiolaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 ReviewDocument2 pagesChapter 9 ReviewReid_pNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Notes OverviewDocument10 pagesUnit 1 Notes Overviewcjchen2810No ratings yet

- Eng-Review of Willem A. VanGemeren (Ed.), New International Dictionary of Old Testament TheologyDocument69 pagesEng-Review of Willem A. VanGemeren (Ed.), New International Dictionary of Old Testament TheologyLuis Echegollen100% (1)

- Ge E3 (LP2)Document20 pagesGe E3 (LP2)Jomar LomentigarNo ratings yet

- HS712EX RiversandCivilizationsDocument11 pagesHS712EX RiversandCivilizationsPraveen RayapatyNo ratings yet

- The First CivilizationDocument31 pagesThe First CivilizationMay Khin NyeinNo ratings yet

- Mesopotamian CivilizationDocument73 pagesMesopotamian CivilizationAvadhesh Kumar Singh100% (2)

- 7000 Years of Iranian ArtDocument200 pages7000 Years of Iranian ArtЃорѓи Поп-ЃорѓиевNo ratings yet

- Class 11 History Notes Chapter 2 Writing and City Life - Learn CBSEDocument7 pagesClass 11 History Notes Chapter 2 Writing and City Life - Learn CBSERupa GanguliNo ratings yet

- River Valley Civilizations: Egyptian Wood CarvingDocument14 pagesRiver Valley Civilizations: Egyptian Wood CarvingSHREYA SHETTYNo ratings yet

- VERDERAME 2012 A Selected Bibliography of Ancient Mesopotamian Medicine (JMC 20, 1-42 DRAFT)Document41 pagesVERDERAME 2012 A Selected Bibliography of Ancient Mesopotamian Medicine (JMC 20, 1-42 DRAFT)Lorenzo VerderameNo ratings yet

- Passage 1: Set 1 QuestionsDocument3 pagesPassage 1: Set 1 QuestionssathiyasuthanNo ratings yet

- MesopotamiaDocument7 pagesMesopotamiamangla.kasak15No ratings yet

- Extensive Afghan HistoryDocument468 pagesExtensive Afghan HistoryAzam AyoubiNo ratings yet

- Cradle of Civilization - Samuel Noah Kramer (1967)Document184 pagesCradle of Civilization - Samuel Noah Kramer (1967)Ludwig Szoha100% (1)

- (Horowitz, Wayne Oshima, Takayoshi Sanders, SethDocument123 pages(Horowitz, Wayne Oshima, Takayoshi Sanders, SethAyar IncaNo ratings yet

- 1 - Pournelle Da Crawford - The Sumerian WorldDocument20 pages1 - Pournelle Da Crawford - The Sumerian WorldBaroso SimoneNo ratings yet

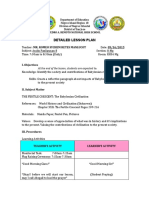

- Detailed Lesson Plan: I. ObjectivesDocument9 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan: I. ObjectivesBernard Vincent Guitan MineroNo ratings yet

- Ancient SumerDocument10 pagesAncient SumerBekka ReyesNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Organizational Behaviour Concepts Controversies Applications Sixth Canadian Edition Canadian 6th Edition Langton Test Bank PDFDocument36 pagesDwnload Full Organizational Behaviour Concepts Controversies Applications Sixth Canadian Edition Canadian 6th Edition Langton Test Bank PDFmekwetingoy100% (14)

- CIVILIZATIONDocument10 pagesCIVILIZATIONCrizel Dane Abalos DamoNo ratings yet

- Strood-The Great Kings of Asia PDFDocument29 pagesStrood-The Great Kings of Asia PDFRosa OsbornNo ratings yet

- Full Download Precalculus Enhanced With Graphing Utilities 7th Edition Sullivan Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterDocument36 pagesFull Download Precalculus Enhanced With Graphing Utilities 7th Edition Sullivan Solutions Manual PDF Full Chaptertransumebavaroyvo0ed3100% (20)

- Egypt, The Kingdom of Kush, and MesopotamiaDocument2 pagesEgypt, The Kingdom of Kush, and MesopotamiaAli B. AlshehabNo ratings yet

- Fertile Crescent: Bronze AgeDocument3 pagesFertile Crescent: Bronze AgeCedy PlatillaNo ratings yet

- TheGodsoftheCeltsandtheIndo EuropeansRevised2019Document517 pagesTheGodsoftheCeltsandtheIndo EuropeansRevised2019Kurt Zepeda100% (1)