Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Casestudymaria

Uploaded by

api-246002293Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Casestudymaria

Uploaded by

api-246002293Copyright:

Available Formats

Module 8 Assignment EDU 615 Case Study: Maria Kari Robert 10.26.

12

Maria is a student I have known for about four years. She was a student of mine as an eighth grader and, now that I have transitioned to high school, she is in my biology class. Maria is sixteen years old and currently a junior. This is the second year in biology for Maria, as she did not pass the class last year. Her academic performance and grades in other classes tend to rollercoaster up and down. The core classes (math, English, science, and history) are where she has the most struggles. One week she may be passing English and science, the next its only history. Her math skills are currently the lowest of her core classes, with science a close second. Her other teachers have mentioned that while she seems to try, she is easily discouraged and gives up. Socially, Maria seems to be very well adjusted. I have seen her interact with her peers outside of the classroom and the atmosphere always seems to be pleasant and light. She has mentioned a desire to pursue a career in cosmetology after high school, and stated that she doesnt understand the need to learn all this stuff she isnt going to need later. This is worrisome, as it is comments like these that lead to decisions to drop out of school. Marias belief that she is incapable of understanding

the material presented in high school could lead her to feel she has no other option than to drop out. Marias home life, for the most part, is a stable one. Her parents emigrated from Mexico many years ago. Maria was born in the United States. Both her parents work minimum wage jobs and are often away from the home to ensure that the family is financially taken care of. I have spoken with Marias mother on a couple of occasions, but she doesnt speak much English, so communication can be challenging. I have gathered, though, that both Marias parents value her education and hope that she does well in school. Within the last year the family suffered a terrible tragedy in the loss of an uncle. This type of loss is certainly an influence on Marias emotional stability and can definitely translate into academics as well. The first day I chose to observe Maria was a day in which the class was introduced to new material. We began with a discussion of how plants conduct photosynthesis. I tried to draw from the students any prior knowledge they had from earlier grade levels. Maria did not volunteer any information during the discussion. I then posed another question, but instead of a whole group discussion, I asked that the students share their thoughts with their tablemates. I noticed that at Marias table there was animated discussion, but again Maria was not a part of it. She tended to sit quietly and absorb what the others were saying. I ventured over to their table to listen more closely and then asked a question to Maria specifically. Her look translated to that of sheer terror and she simply said that she didnt know. It was my hope that in the smaller setting of her group she would feel more comfortable participating. From

this point we settled in to take a few notes and I could see that Maria was noticeably more relaxed. My next observation of Maria came in the form of a lab that related to the work we had been doing on photosynthesis. The set up was typical of a classroom science lab. The students were required to read through the lab procedures and record any pertinent information into their lab notebooks. The students are organized into groups of four and are required to work together, but also turn in individual lab reports. Maria seemed very comfortable with the portion of the lab that required the step-by-step procedures to be followed. She was instrumental in reading through each instruction and paid close attention that each instruction was followed accurately. She constructed the data table as well as the necessary graph without much assistance. These were areas where she seemed quite confident in her abilities. At other points in the lab, where synthesis and analysis of the data was necessary, I noticed that Maria once again deferred to her lab partners. She didnt contribute much to the discussion of the results. My next opportunity for observation came the day we took the test for the unit on photosynthesis. I reminded the students at various times throughout the week before that the test was approaching. I noticed too that each time I did Maria would get a look of dread on her face. I made sure that I spoke to her specifically and asked how her studying was coming along. She would give me a weak smile and say that she was doing fine. The day of the test was greeted with moans and groans as I asked the students to put everything away but their pencils. Maria looked extremely anxious and asked if she could please take the test on another day. I expressed that

everyone was given plenty of time to prepare for the test, but that if she needed extra time in order to finish I could arrange for her to come in during lunch. She seemed to relax a little after that but still looked noticeably nervous. As the test progressed, and I walked around the room monitoring, I noticed that Maria was not making much progress at all. She was still on page one when others had moved on to page two or three. I asked her if she would feel more comfortable if I moved her away from the rest of the class and she said that she would. Once sitting at a table by herself she continued to work, albeit slowly. On several occasions she called me over to help clarify questions for her. My strategy each time was to try and remind her of the instances in which we covered that material in class, specific things like the day or what activity we worked on. This seemed to help a little so I made it a point to linger at her seat longer than others. For my final observation I wanted to see Maria work in a class other than my own. I used my conference period for this observation. It turned out during this time Maria was in an elective class, graphic design. What I noticed was that the pressure seemed to be off. Maria seemed like a new person. She was engaged in what she was doing and seemed to be thoroughly enjoying herself. She and another student were working on a design for a new restaurant logo. I spoke briefly with her teacher about her progress and performance. He stated that she is doing well for the most part. Occasionally there is a late assignment but not enough to cause her grade to suffer terribly. A key strategy to apply with Maria, as with any student, is pre-assessment. It is important that I understand where Marias strengths and weaknesses are for

particular content so that I can adequately tailor and adjust an upcoming lesson (Chapman & King, 2012). It would be a disservice to Maria if I start my lesson with content or activities that are beyond her skill level. It is my feeling that this is the point at which she shuts down and simply considers the material beyond her abilities, when in fact she just hasnt been given the proper foundation on which to build her skills. It is important also to assess students while a unit is in progress (Gregory & Chapman 2007). Maria might possibly feel less stress if she can demonstrate her skills a little at a time as opposed to everything all at once at the end of a unit. Maria attributes much of her struggles and her poor performance in her classes to lack of intelligence: she doesnt feel that she is smart enough to do the work. It is this mindset that may cause Maria to feel like she has no control over how she performs. If giving Maria an assignment in smaller pieces helps her to see that she is in control, then her performance may improve (Anderman & Anderman, 2010). Students need to feel some sense of control over what they do in their lives. Maria needs guidance and assurance that when she is working on something she is headed in the right direction. It would not be a good idea to hand her an assignment and then ask her to figure it out on her own. When she is working on an assignment individually it is important to check in with her regularly to make sure she is on the right track. During lab work or group activities it is helpful to organize the group so there is someone who can mentor Maria. Getting an explanation from a student in your peer group may be the difference in understanding or not understanding. Her mentor is gaining because when you have to teach someone else you have a

tendency to retain the information better, and Maria is getting to hear the information from another perspective (Gregory & Chapman, 2007). Motivating our students can be a complicated process. There are many factors at work. How does a student see himself or herself? How does the teacher see the student? What do the students peers think of him or her? What about their parents? It all boils down to the relationships that we have in our lives. Good solid relationships with parents, teachers and peers foster not only strong emotional, social and intellectual performance but also enhanced feelings of self-efficacy (Connell & Wellborn, 1991, as cited in Andrew & Dowson, 2009). The numerous influences and relationships in the lives of our students are out of our control. We need to focus on the areas that we have some control over. It is important for teachers to pay attention to what students attribute their successes or failures to. Does the student feel they did poorly on an assignment because of lack of intelligence or due to the fact that they did not prepare well or properly apply him or herself to a task? The former may cause the student to feel as if he or she has no control, while the latter gives them the sense of control (Anderman & Anderman, 2010). It is imperative that as teachers we give back to our students that sense of control. Structure our lessons in ways that allow them to feel as if they can accomplish the task. Our lessons should be challenging but not so much as to be distressing (Gregory & Chapman, 2007).

References: Andrew, J. M., & Dowson, M. (2009). Interpersonal relationships, motivation, engagement, and achievement: Yields for theory, current issues, and educational practice. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 327-365. Retrieved from http://0search.proquest.com.lilac.une.edu/docview/214136090?accountid=12756 Anderman, E. M. & Anderman, L. H. (2010). Classroom Motivation. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education Inc. Chapman, C., King, R. (2012). Differentiated Assessment Strategies: One tool doesnt fit all. (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. Gregory, G. H., & Chapman, C. (2007). Differentiated Instructional Strategies: One size doesnt fit all. (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

You might also like

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- CurriculumdevelopmentDocument5 pagesCurriculumdevelopmentapi-246002293No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- PlcfeedbackDocument4 pagesPlcfeedbackapi-246002293No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- PLC InterventionDocument5 pagesPLC Interventionapi-246002293No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Implementing Cooperative Learning Strategies To Improve Student EngagementDocument30 pagesImplementing Cooperative Learning Strategies To Improve Student Engagementapi-246002293No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- StudentcasestudiesmotivationDocument7 pagesStudentcasestudiesmotivationapi-246002293No ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Curriculum Development UnitDocument24 pagesCurriculum Development Unitapi-246002293No ratings yet

- Robert Differentiated Instruction Lesson PlanDocument13 pagesRobert Differentiated Instruction Lesson Planapi-246002293No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Kari Robert2013mDocument3 pagesKari Robert2013mapi-246002293No ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

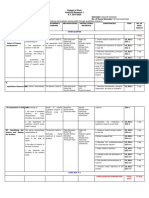

- Budget of Work in PR1Document4 pagesBudget of Work in PR1Ronnie LucidoNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The Impact of Reading Graphic Novels For Pleasure On Enhancing Third Year Pupils' Reading Comprehension at The Elementary LevelDocument114 pagesThe Impact of Reading Graphic Novels For Pleasure On Enhancing Third Year Pupils' Reading Comprehension at The Elementary LevelÄy MênNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Class ProgramsDocument30 pagesClass Programsludivino escardaNo ratings yet

- Module Retrieval and Distribution FormDocument1 pageModule Retrieval and Distribution FormHoney Crystel PadocNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Tad Barber's School Board Resignation LetterDocument1 pageTad Barber's School Board Resignation LetterJay AndersonNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Amazon Leadership Principles - Icons - External UsageDocument4 pagesAmazon Leadership Principles - Icons - External UsageRajagopalanNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- 7003-Documents Required For Non-ECRDocument3 pages7003-Documents Required For Non-ECR108databoxNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- International Law AustraliaDocument209 pagesInternational Law AustraliaBasit Qadir100% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Undergraduate Prospectus 2014Document18 pagesUndergraduate Prospectus 2014Rema RomanNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Term Paper Guidelines: Your Obligation To The ReaderDocument8 pagesTerm Paper Guidelines: Your Obligation To The ReaderNur 'AtiqahNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis ProposalDocument2 pagesPHD Thesis Proposalppnelson85No ratings yet

- ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN 2 COURSEDocument13 pagesARCHITECTURAL DESIGN 2 COURSEPark JeongseongNo ratings yet

- Literature and Philosophy, MA - 2018-19Document15 pagesLiterature and Philosophy, MA - 2018-19Teacher ShielaNo ratings yet

- ACC-1: Organizing Child Care ServicesDocument8 pagesACC-1: Organizing Child Care Servicesmithu11No ratings yet

- 2014 The US-ASEAN Fulbright Initiative Application FormDocument18 pages2014 The US-ASEAN Fulbright Initiative Application Forminezt12No ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Big 4 Interview QuestionsDocument4 pagesBig 4 Interview Questionsxanax_1984No ratings yet

- ModuleDocument8 pagesModuleAquilah Magistrado GarciaNo ratings yet

- Virginia Woolf and Feminism by Şeyda BİLGİNDocument12 pagesVirginia Woolf and Feminism by Şeyda BİLGİNŞeyda BilginNo ratings yet

- TLE ICT Technical Drafting Grade 10 LMDocument181 pagesTLE ICT Technical Drafting Grade 10 LMnef blanceNo ratings yet

- "Biomedical Waste Management": Project ReportDocument16 pages"Biomedical Waste Management": Project ReportAnkur UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Cell Phone Should Be Allowed in The ClassDocument4 pagesCell Phone Should Be Allowed in The Classapi-314292483No ratings yet

- LBCC Policy Procedure Disclosure Statement 4-30-20151Document7 pagesLBCC Policy Procedure Disclosure Statement 4-30-20151Extreme DaysNo ratings yet

- 3rd Grade MathDocument3 pages3rd Grade MathCheryl DickNo ratings yet

- Certified School List 12-05-23Document247 pagesCertified School List 12-05-23yaahyakaleabNo ratings yet

- Sample Lesson Plan - 1Document3 pagesSample Lesson Plan - 1Davidson isaack100% (1)

- Attitude and Motivation Towards English LearningDocument8 pagesAttitude and Motivation Towards English LearningteeshuminNo ratings yet

- Mi Mi 4Document42 pagesMi Mi 4Aishik BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Contact Theory and Attitudes of Children inDocument10 pagesContact Theory and Attitudes of Children inBranislava Jaranovic VujicNo ratings yet

- Modernization in Higher EducationDocument15 pagesModernization in Higher Educationlegal CellNo ratings yet

- Elements of Visual Arts Detailed Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesElements of Visual Arts Detailed Lesson PlanGene70% (10)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)