Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Taxation (Income Tax) - Pp41-60

Uploaded by

Iya PadernaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Taxation (Income Tax) - Pp41-60

Uploaded by

Iya PadernaCopyright:

Available Formats

CASE CIR v. Philippine Airlines, Inc., GR No.

160528, 9 October 2006

TAXATION I (DEAN GRUBA) DOCTRINE Q: What is taxable income? How is it computed?

CIR v. Philippine Airlines, Inc., GR No. 180066, 7 July 2009

Under PALs franchise, the basic corporate income tax or franchise tax, whichever is lower, that is payable by PAL in a given taxable year shall be in lieu of all other taxes. Is the 20% final withholding tax on bank deposits included in all other taxes? In CIR v. Philippine Airlines, Inc., the Supreme Court held affirmatively. [As a consequence, PAL was held to be entitled to a refund of the 20% FWT it paid on bank deposits for the period starting March 1995 through November 1997.] A corporate income tax liability has two components: the general rate of now 30%, and the specific final rates for certain passive incomes. In arriving at the taxable income of PAL, are these passive incomes taken into consideration? No. The definition of gross income is broad enough to include all passive incomes subject to specific rates or final taxes. However, since these passive incomes are already subject to different rates and taxed finally at source, they are no longer included in the computation of gross income, which determines taxable income. Q: What is taxable income? How is it For its fiscal year ending 31 March 2001 (FY computed? 2000-2001), PAL incurred zero taxable income, which left it with unapplied creditable Under PALs franchise, the basic corporate withholding tax in the amount of P2.3M. PAL income tax or franchise tax, whichever is did not pay any MCIT for the period. In a letter lower, that is payable by PAL in a given taxable dated 12 July 2002, addressed to CIR, PAL year shall be in lieu of all other taxes. Is requested for the refund of its unapplied

FACTS The case involves the application of the tax provision in PALs franchise defining its liability for taxes. P.D. 1590, the legislative franchise of PAL granted it an option to pay the lower of two alternatives: (1) the basic corporate income tax based on PALs annual net taxable income computed in accordance with the provisions of the NIRC, or (2) a franchise tax of two percent of gross revenues. Availment of either of these two alternatives shall exempt the airline from the payment of all other taxes. On this basis, a claim for refund of the 20% final withholding tax on its interest income with various banks was instituted.

MCIT included in all other taxes? In CIR v. Philippine Airlines, Inc., the Supreme Court held affirmatively. [As a consequence, PAL was held not liable to pay MCIT for the fiscal year 2000-2001.] Although regular corporate income tax and minimum corporate income tax are both income taxes, they are computed differently, i.e., varying rates and bases. The basis for regular corporate income tax is taxable income, while the basis for minimum corporate income tax is gross income. It must be further noted that the gross income base for MCIT is slightly different from gross income under Section 32 of the 1997 Tax Code. Taxable income is defined under Section 31 of the NIRC of 1997 as the pertinent items of gross income specified in the said Code, less the deductions and/or personal and additional exemptions, if any, authorized for such types of income by the same Code or other special laws. The gross income, referred to in Section 31, is described in Section 32 of the NIRC of 1997 as income from whatever source, including compensation for services; the conduct of trade or business or the exercise of profession; dealings in property; interests; rents; royalties; dividends; annuities; prizes and winnings; pensions; and a partners distributive share in the net income of a general professional partnership. On the other hand, gross income in relation to MCIT is understood to mean gross receipts, less sales returns, allowances, discounts and cost of services. Noticeably, inclusions in andexclusions/deductions from gross income

creditable withholding tax for FY 2000-2001. PAL attached to its letter the following: (1) Schedule of Creditable Tax Withheld at Source for FY 2000-2001; (2) Certificates of Creditable Taxes Withheld; and (3) Audited Financial Statements. Acting on the aforementioned letter of PAL, the Large Taxpayers Audit and Investigation Division 1 (LTAID 1) of the BIR Large Taxpayers Service (LTS), issued Tax Verification authorizing Revenue Officer Cueto to verify the supporting documents and pertinent records relative to the claim of PAL for refund of its unapplied creditable withholding tax for FY 2000-20001. LTAID 1 Chief Linsangan invited PAL to an informal conference. BIR officers and PAL representatives attended the scheduled informal conference, during which the former relayed to the latter that the BIR was denying the claim for refund of PAL and, instead, was assessing PAL for deficiency MCIT for FY 2000-2001. The PAL representatives argued that PAL was not liable for MCIT under its franchise. The BIR officers then informed the PAL representatives that the matter would be referred to the BIR Legal Service for opinion.

for MCIT purposes are limited to those directly arising from the conduct of the taxpayers business. It is, thus, more limited than the gross income used in the computation of basic corporate income tax. Nitafan v. CIR, GR No. 78780, 23 July 1987 Q: Are the salaries of the members of the judiciary subject to income tax? The Chief Justice has previously issued a directive to the Fiscal Management and Budget Office to continue to deduct withholding taxes from the salaries of the Are salaries of judges subject to income tax? Yes. Nitafan v. CIR confirmed that during their Justices of the Supreme Court and other continuance in office, judges and justices enjoy members of the judiciary. This was affirmed by the constitutional protection against decrease the Supreme Court En Banc on 4 December 1987. RTC judges seek to prohibit or enjoin the of their salaries. However, the salaries of Commissioner of the Internal Revenue and the members of the judiciary are subject to the Financial Officer of the Supreme Court from general income tax applied to all taxpayers. making any deduction of withholding taxes from their salaries. British Overseas Airways Corporation Q: What is gross income? (BOAC) is a 100% British Government In CIR v. British Overseas Airways Corporation, Owned airline corporation organized under BOAC was a British Government-owned the laws of the UK. BOAC maintains a corporation engaged in the international general sales agent (of its tickets) in the airline business. As such, it operated air Philippines namely Warner and Barnes transportation service and sold transportation and Qantas Airways. It also did not have tickets over the routes of the other airline landing rights in the Philippines. It was members. For the years 1959 to 1971, BOAC had no landing rights for traffic purposes in the assessed deficiency income taxes by CIR Philippines. It did not carry passengers and/or in the years 1959-1963 and 1968-1979. However, on appeal, the CTA held that the cargo to and from the Philippines, although proceeds of sales of BOAC tickets in the from 1959 to 1971, BOAC maintained a Philippines do not constitute BOAC income general sales agent in the country which was responsible for selling BOAC tickets covering from Philippine sources since no service of passengers and cargoes. The CIR issued an carriage of passengers or freight was assessment against BOAC for deficiency performed by BOAC within the Philippines income taxes for the years 1959 to 1971 for therefore said income is not subject to

CIR v. British Overseas Airways Corporation, GR Nos. L-65773-74, 30 April 1987.

the sale of tickets in the Philippines for air transportation. Did BOACs income from the sale of tickets in the Philippines come from sources within the Philippines and thus taxable under Philippine income tax laws? The Supreme Court held in the affirmative. Although the enumeration in now Section 32(A) of the 1997 Tax Code does not include income from the sale of tickets for international transportation, the definition of gross income is broad and comprehensive to include proceeds from the sale of transport documents. *Section 32 of the 1997 Tax Code], by its language, does not intend the enumeration to be exclusive. It merely directs that the types of income listed therein be treated as income from sources within the Philippines. A cursory reading of the section will show that it does not state that it is an allinclusive enumeration, and that no other kind of income may be so considered." Sison v. Ancheta, GR No. L-59431, 25 July 1984 Q: Compensation for services in whatever form paid; illustrative case. See the case of Sison v. Ancheta which was governed by the 1977 Tax Code. Under the old code, a higher tax rate was imposed on professional and business income than on compensation income. Sison attacked the distinction made by law on such grounds as equal protection and uniformity in taxation. The Supreme Court justified the difference in treatment, thus: Taxpayers who are recipients of compensation income are set apart as a class. As there is practically no overhead expense, these taxpayers are not

income tax. The CTA held that the place where services are rendered determines the source of the income. The petitioner contends that the revenue derived by BOAC from sales of tickets in the Philippines are taxable and that BOAC should be considered a resident foreign corporation and accordingly taxed as such.

Sison, as a taxpayer, questions the validity of Section 1 of BP 135 which amended Section 21 of the NIRC of 1977. BP 135 provides for rates of tax on citizens or residents on: (a) taxable compensation income, (b) taxable net income, (c) Royalties, prizes and other winnings, (d) Interest from bank deposits and yield or any other monetary benefit from deposit substitutes and from trust fund and similar arrangements, (e) Dividends and share of individual partner in the net profits of taxable partnership, and (e) Adjusted gross income. Sison characterizes the law as arbitrary, amounting to class legislation, oppressive and capricious. Petitioner invokes the Equal

Tan v. del Rosario, GR Nos. 109289 and 109446, 3 October 1994

entitled to make deductions for income tax purposes because they are in the same situation more or less. On the other hand, in the case of professionals in the practice of their calling and businessmen, there is no uniformity in the costs or expenses necessary to produce their income. It would not be just then to disregard the disparities by giving all of them zero deduction and indiscriminately impose on all alike the same tax rates on the basis of gross income. There is ample justification then for the Batas Pambansa to adopt the gross system of income taxation to compensation income, while continuing the system of net income taxation as regards professional and business income. Q: Gross income derived from the conduct of trade or business or the exercise of a profession; illustrative case. The case of Tan v. del Rosario dealt with the constitutionality of RA No. 7496, also commonly known as the Simplified Net Income Taxation Scheme (SNIT), amending certain provisions of the old Tax Code. One argument raised by petitioners was that the law now taxed single proprietorships and professionals differently from the manner it imposed tax on corporations and partnerships. Another argument was that general professional partnerships should not be treated differently from ordinary business partnerships. The Supreme Court held that the classification made between single proprietorships and professionals on the one hand, and corporations and partnerships on

Protection and Due Process clauses, as well as the rule requiring Uniformity in Taxation.

Petitioners assail the constitutionality of RA7496, known as the Simplified Net Income Taxation Scheme (SNIT), which amended certain provisions of the NIRC. They also seek a declaration that public respondents have exceeded their rule-making authority in applying SNIT to general professional partnerships through the issuance of Revenue Regulations No 2-93, specifically Section 6 thereof

CIR v. Court of Appeals, GR No. 108576, 20 January 1999

the other, was valid. Furthermore, as regards the first group, i.e., single proprietorships and professionals: There is, then and now, no distinction in income tax liability between a person who practices his profession alone or individually and one who does it through partnership (whether registered or not) with others in the exercise of a common profession. Indeed, outside of the gross compensation income tax and the final tax on passive investment income, under the present income tax system all individuals deriving from any source whatsoever are treated in almost invariably the same manner and under a common set of rules. Q: Dividends; illustrative case Don Andres Soriano, a citizen and resident of the United States, formed the corporation "A. At issue in CIR v. Court of Appeals was the Soriano Y Cia", predecessor of ANSCOR. taxability of the shares of stock in ANSCOR ANSCOR is wholly owned and controlled by owned by the estate of Don Andres Soriano as the family of Don Andres, who are all nonwell as Don Andres Sorianos widow, Doa resident aliens. Don Andres died, but his Carmen Soriano. On various dates, (1) the estate continued to receive stock dividends as estate and Doa Carmen exchanged a portion well as his wife Doa Carmen Soriano. of their common shares for preferred shares, Pursuant to a board resolution, ANSCOR and (2) ANSCOR redeemed a portion of the redeemed a stated in the Board Resolutions, common shares owned by the estate and ANSCOR's business purpose for both Doa Carmen. ANSCORs business purpose for redemptions of stocks is to partially retire said the redemption of stocks was to partially retire stocks as treasury shares in order to reduce said stocks as treasury shares in order to the company's foreign exchange remittances reduce the companys foreign exchange in case cash dividends are declared. ANSCOR remittances in case cash dividends were also reclassified some of Doa Carmens declared. Subsequently, ANSCOR was issued common shares to preferred shares. After an assessment for deficiency withholding tax examining ANSCOR's books of account and at source based on the transactions of records, Revenue examiners issued a report exchange and redemption of stocks. Regarding proposing that ANSCOR be assessed for the exchange of stocks, the Supreme Court deficiency withholding tax-at-source based on

found that there was no change in the proportional interest of the estate and Doa Carmen before and after the exchange. The exchange transaction did not result into a flow of wealth and hence, there was no income tax liability. As regards the redemption of stocks, the issue was, particularly, whether ANSCORs redemption of stocks from its stockholder as well as the exchange of common with preferred shares could be considered as essentially equivalent to the distribution of taxable dividends, making the proceeds thereof taxable income. The Supreme Court started by saying that the stock dividends, strictly speaking, represent capital and do not constitute income to its recipient. The mere issuance of stock dividends is not yet subject to income tax. As capital, the stock dividends postpone the realization of profits. However, a redemption of the stocks converts into money the stock dividends which become a realized profit or gain and consequently, the stockholders separate property. As realized income, the proceeds of the redeemed stock dividends can be reached by income taxation regardless of the existence of any business purpose for the redemption. Here, the proceeds of the redemption of the stock dividends were deemed taxable dividends, i.e., income subject to income tax which was required to be withheld at source. The determining factor for the imposition of income tax is whether any gain or profit was derived from a transaction. Furthermore, there are 3 elements in the imposition of

the transactions of exchange and redemption of stocks. ANSCOR filed a petition for review with the CTA assailing the tax assessments on the redemptions and exchange of stocks. The CTA ruled that ANSCORs redemption and exchange of the stocks of its foreign stockholders cannot be considered as "essentially equivalent to a distribution of taxable dividends" under Section 83(b) of the then 1939 Internal Revenue Act. ANSCOR avers that it has no duty to withhold any tax either from the Don Andres estate or from Doa Carmen based on the two transactions, because the same were done for legitimate business purposes which are (a) to reduce its foreign exchange remittances in the event the company would declare cash dividends, and to (b) subsequently "filipinized" ownership of ANSCOR, as allegedly, envisioned by Don Andres. It likewise invoked the amnesty provisions of P.D. 67.

income tax, namely: (1) there must be gain or profit; (2) the gain or profit is realized or received, actually or constructively; and (3) the gain or profit is not exempted by law or treaty from income tax. Any business purpose as to why or how the income was earned by the taxpayer is not a requirement. Income tax is assessed on income received from any property, activity or service that produces the income because the Tax Code stands as an indifferent neutral party on the matter where income comes from. El Oriente Fabrica de Tabacos, Inc. v. Posadas, GR No. 34774, 21 September 1931 Q: Are proceeds of life insurance policies excluded from gross income? Section 32(B) of the 1997 Tax Code partly provides: The following items shall not be included in gross income and shall be exempt from taxation under this title: xxx The proceeds of life insurance policies paid to the heirs or beneficiaries upon the death of the insured, whether in a single sum or otherwise, but if such amounts are held by the insurer under an agreement to pay interest thereon, the interest payments shall be included in gross income. The law is clear that the proceeds of life insurance policies paid to individual beneficiaries are excluded from gross income. Suppose the proceeds of a life insurance policy are paid to a corporate beneficiary upon the death of the insured, are such proceeds likewise excluded from gross income? In El Oriente Fabrica de Tabacos, Inc. v. Posadas, El Oriente took out insurance on the life of its manager, who had more than 35 El Oriente in order to protect itself against the loss that it might suffer by reason of the death of its manager, A. Velhagen, who had had more than thirty-five (35) years of experience in the manufacture of cigars in the Philippines, procured from the Manufacturers Life Insurance Co., of Toronto, Canada, thru its local agent E. E. Elser, an insurance policy on the life of the said A. Velhagen for the sum of $50,000, United States currency designating itself as the beneficiary. El Oriente paid for the premiums due thereon and charged as expenses of its business all the said premiums and deducted the same from its gross incomes as reported in its annual income tax returns, which deductions were allowed upon a showing that such premiums were legitimate expenses of its business. Upon the death of A. Velhagen in 1929, the El Oriente received all the proceeds of the said life insurance policy, together with the

Santos v. Servier Philippines, Inc., GR No. 166377, 28 November 2008

years of experience in the manufacture of cigars in the Philippines, to protect itself against the loss it might suffer by reason of the death of its manager. The Supreme Court held that: Considering, therefore, the purport of the stipulated facts, considering the uncertainty of Philippine law, and considering the lack of express legislative intention to tax the proceeds of life insurance policies paid to corporate beneficiaries, particularly when in the exemption in favor of individual beneficiaries in the chapter on this subject, the clause is inserted exempt from the provisions of this law, we deem it reasonable to hold the proceeds of the life insurance policy in question as representing an indemnity and not taxable income. *Note that this case was decided in 1931, and that in our present Tax Code, the clause exempt from provisions of this law does not appear anywhere in Section 32 of the code.] Q: When are retirement benefits excluded from gross income?

interests and the dividends accruing thereon, aggregating P104,957.88 CIR assessed El Oriente for deficiency taxes because El Oriente did not include as income the proceeds received from the insurance.

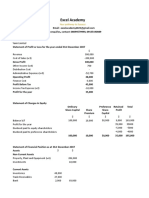

Santos was the Human Resource Manager of Servier Philippines, Inc. Santos attended a meeting of all human resource managers of In Santos v. Servier Philippines, Inc., Santos was Servier, held in Paris, France. Since the last day the human resource manager of Servier of the meeting coincided with the graduation Philippines, Inc. since 1991. In 1998, while on of Santos only child, she arranged for a European vacation with her family right after vacation in Paris, Santos suffered from a the meeting. She, thus, filed a vacation leave. sudden attack of alimentary allergy. Despite Santos, together with her husband Antonio P. months of medical treatment, Santos did not Santos, her son, and some friends, had dinner fully recover mentally and physically. Servier Philippines, Inc. was constrained to terminate at Leon des Bruxelles, a Paris restaurant Santos services effective 31 August 1999. As a known for mussels as their specialty. While having dinner, Santos complained of stomach consequence thereof, Servier Philippines, Inc. pain, then vomited. Eventually, she was offered Santos a retirement package. Were brought to a hospital where she fell into coma Santos retirement benefits taxable? The

Supreme Court held in the affirmative. For retirement benefits to be exempt from income tax, and hence withholding tax, the taxpayer is burdened to prove the concurrence of the following elements: (1) a reasonable private benefit plan is maintained by the employer; (2) the retiring employee has been in the service of the same employer for at least 10 years; (3) the retiring employee is not less than 50 years of age at the time of his/her retirement; and (4) the benefit had been availed of only once. Here, at the time of her retirement, Santos was only 41 years of age, and had been in the service for more or less 8 years. As such, Section 32(B)(6)(a) of the 1997 Tax Code was inapplicable for failure to comply with the age and length of service requirements. The retirement benefits received by Santos were taxable.

Intercontinental Broadcasting Corporation (IBC) v. Amarilla, GR No. 162775, 27 October 2006

Q: When are retirement benefits excluded from gross income? In Intercontinental Broadcasting Corporation (IBC) v. Amarilla, Quiones, Amarilla, Lagahit, and Otadoy

for 21 days; and later stayed at the ICU for 52 days. The hospital found that the probable cause of her sudden attack was "alimentary allergy. During the time that Santos was confined at the hospital, her husband and son stayed with her in Paris. Santos hospitalization expenses, as well as those of her husband and son, were paid by Servier. Santos was then allowed to go back to the Philippines to continue her medical treatment. She was confined at St. Lukes. During the period of Santos rehabilitation, Servier continued to pay Santos salaries and to assist her in paying her hospital bills. Thereafter, Servier informed Santos that it requested her physician to conduct an evaluation of her condition to determine her fitness to resume her work at the company. It was concluded that she was not fully recovered mentally and physically. Hence, Servier was constrained to terminate Santos services. As a consequence of her termination from employment, Servier offered a retirement package. Of the promised retirement benefit, a portion was withheld allegedly for taxation purposes. Servier also failed to give other benefits in the package. Santos filed a case against Servier. Santos raised the legality of said deduction and stated that it formed an "unpaid balance of the retirement package." Intercontinental Broadcasting Corporation (IBC) employed at its Cebu Station the petitioners Amarilla, Quinones, Lagahit and Otadoy. The four employees retired from the company and received, on staggered basis, their retirement benefits under the collective

retired from IBC. It was agreed that IBC would shoulder the income tax due on the retirement benefits to be received by the four individuals. The Supreme Court first held that the retirement benefits granted to the retirees were taxable. However, the Court acknowledged that IBC bound itself to pay the taxes on the retirement benefits. An agreement to pay the taxes on the retirement benefits as an incentive to prospective retirees and for them to avail of the optional retirement scheme is not contrary to law or to public morals. Petitioner had agreed to shoulder such taxes to entice them to voluntarily retire early, on its belief that this would prove disadvantageous to it. Respondents agreed and relied on the commitment of petitioner. For petitioner to renege on its contract with respondents simply because its new management had found the same disadvantageous would amount to a breach of contract.

bargaining agreement (CBA) between IBC and the bargaining unit of its employees. In the meantime, a salary increase was given to all employees, current and retired. However, when the four retirees demand theirs, the IBC refused and instead informed them that their differentials would be used to offset the tax due on their retirement benefits in accordance with the NIRC. The retirees thus lodged a complaint with the NLRC questioning said withholding. They averred that their retirement benefits were exempt from income tax; and IBC had no authority to withhold their salary differentials. For its part, the IBC averred that the retirement benefits received by employees from their employers constitute taxable income. While retirement benefits are exempt from taxes under the Code, the law requires that such benefits received should be in accord with a reasonable retirement plan duly registered with the BIR after compliance with the requirements therein enumerated. Since its retirement plan in the CBA was not approved by the BIR, the retirees were liable for income tax on their retirement benefits. The Labor Arbiter rendered judgment in favour of the retirees. The NLRC affirmed. IBC appealed to the CA. The CA dismissed the petition and held that the salary differentials of the respondents are part of their taxable gross income, considering that the CBA was not approved, much less submitted to the BIR. However, petitioner could not withhold the corresponding tax liabilities of respondents due to the then existing CBA, providing that such retirement benefits would not be

CIR v. Court of Appeals, GR No. 96016, 17 October 1991

Q: When are retirement benefits excluded from gross income? In CIR v. Court of Appeals, Castaeda retired from the government service as revenue attach in the Philippine Embassy in London. Upon retirement, he received terminal leave pay from which the CIR withheld a certain amount allegedly representing income tax thereon. The issue in this case was whether terminal leave pay received by a government official or employee on the occasion of his compulsory retirement from the government service was subject to income tax, and hence withholding tax. The Supreme Court ruled that terminal leave pay was not a part of the gross income of a government official or employee, but a retirement benefit that was not subject to income tax. Commutation of leave credits is more commonly known as terminal leave. In the exercise of sound personnel policy, the Government encourages unused leaves to be accumulated. The Government recognizes that for most public servants, retirement pay is always less than generous if not meager and scrimpy. A modest nest egg which the senior citizen may look forward to is thus avoided. Terminal leave payments are given not only at the same time but also for the same policy considerations governing retirement benefits.

subjected to any tax deduction, and that any such taxes would be for its account. Castaneda retired from the government service as Revenue Attache in the Philippine Embassy in London. Upon retirement, he received, among other benefits, terminal leave pay from which the CIR withheld a portion allegedly representing income tax thereon. Castaneda filed a claim with the CIR for refund contending that the cash equivalent of his terminal leave is exempt from income tax. He likewise filed a petition for review with the CTA. The CTA ruled in favor of Castaneda and ordered the CIR to refund Castaneda. CA affirmed the decision of the CTA. Hence, this petition by the CIR. The Solgen, acting on behalf of the CIR, contends that the terminal leave pay is income derived from employeremployee relationship; that as part of the compensation for services rendered, terminal leave pay is actually part of gross income of the recipient.

CIR v. Central Luzon Drug Corporation, GR No. 159610, 12 June 2008.

Q: Differentiate between a tax deduction and a tax credit.

Respondent is a domestic corporation primarily engaged in retailing of medicines and pharmaceutical products. Respondent granted

Carlos Superdrug Corp. v. Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), GR No. 166494, 29 June 2007

How may a drugstore treat the 20% discount given to senior citizens? May it be claimed as a tax deduction from gross income or a tax credit? The case of CIR v. Central Luzon Drug Corporation covered the taxable year 1997 and thus applied the old rule under RA No. 7432, i.e., the 20% senior citizens discount could be claimed as a tax credit. However, with the effectivity of RA No. 9257 (21 March 2004), there is now a new tax treatment for senior citizens discount granted by all covered establishments. This discount should be considered as a deductible expense from gross income and no longer as tax credit. Q: Differentiate between a tax deduction and a tax credit. In Carlos Superdrug Corp. v. Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), petitioners were drugstores assailing the constitutionality of RA No. 9257, particularly, the validity of the tax deduction scheme as a reimbursement mechanism for the 20% senior citizens discount. A tax deduction was differentiated from a tax credit in this wise: the tax deduction scheme does not fully reimburse petitioners for the discount privilege accorded to senior citizens. This is because the discount is treated as a deduction, a tax-deductible expense that is subtracted from the gross income and results in a lower taxable income. Stated otherwise, it is an amount that is allowed by law to reduce the income prior to the application of the tax rate to compute the amount of tax which is due. Being a tax deduction, the discount does not

20% percent sales discount to qualified senior citizens on their purchase of medicines. Respondent filed for a tax refund/credit alledgly arising from the 20% sales discount granted by respondent to qualified senior citizens in compliance with RA 7432. Unable to obtain an affirmative response from petitioner, Respondent elevated its claim to the CTA. The CTA dismissed the petition but eventually granted the motion for reconsideration ordering petitioner to issue a Tax Credit certificate. CA affirmed. Hence, this petition. Petitioners are domestic corporations and proprietors operating drugstores in the Philippines. Petitioners assail the constitutionality of Section 4(a) of RA 9257, otherwise known as the Expanded Senior Citizens Act of 2003. Section 4(a) of RA 9257 grants twenty percent (20%) discount as privileges for the Senior Citizens. Petitioner contends that said law is unconstitutional because it constitutes deprivation of private property.

reduce taxes owed on a peso for peso basis but merely offers a fractional reductions in taxes owed. On the other hand, a tax credit is a peso-for-peso deduction from a taxpayers tax liability due to the government of the amounts of seniors citizens discount given by the covered establishment. Such establishment recovers the full amount and hence, the government shoulders 100% of the discounts granted. Ultimately, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of RA No. 9257 primarily on the ground that the law was a legitimate exercise of police power. Basilan Estates, Inc. v. CIR, GR No. L-22492, 5 September 1967 Basilan Estates, Inc. claimed deductions for the depreciation of its assets on the basis of their acquisition cost. As of January 1, 1950 it changed the depreciable value of said assets In Basilan Estates, Inc. v. CIR, petitioner was a by increasing it to conform with the increase domestic corporation engaged in the coconut in cost for their replacement. Accordingly, industry. In 1953, petitioner received a from 1950 to 1953 it deducted from gross deficiency income tax assessment partly due to disallowed deductions from its gross income income the value of depreciation computed on the reappraised value. in the form of depreciation, travelling and miscellaneous expenses. One issue tackled was CIR disallowed the deductions claimed by petitioner, consequently assessing the latter of whether depreciation should be determined deficiency income taxes. on the acquisition cost or on the reappraised value of the assets. The Supreme Court ruled that the income tax law did not authorize the depreciation of an asset beyond its acquisition cost. A deduction over and above such cost must be disallowed. The reason is that deductions from gross income are privileges, not matters of right. They are not created by implication but upon clear expression in the law. Moreover, the recovery, free of income tax, of Q: In general, what is the treatment accorded to deductions from gross income?

an amount more than the invested capital in an asset will transgress the underlying purpose of a depreciation allowance. For then what the taxpayer would recover will be not only the acquisition cost, but also some profit. Recovery in due time thru depreciation of investment made is the philosophy behind depreciation allowance; the idea of profit on the investment made has never been the underlying reason for the allowance of a deduction for depreciation. Aguinaldo Industries Corporation v. CIR, GR No. L-29790, 25 February 1982 Q: In general, what is the treatment accorded to deductions from gross income? In Aguinaldo Industries Corporation v. CIR, when petitioner sold its property in Muntinglupa, the corporate officers of petitioner were given bonuses. The amount representing these bonuses was claimed by petitioner as a deductible business expense. The Supreme Court held that the bonuses could not be deemed a deductible expense for tax purposes, even if the aforesaid sale could be considered as a transaction for carrying on the trade or business of the petitioner and the grant of the bonus to the corporate officers pursuant to petitioners by-laws could, as an intra-corporate matter, be sustained. Citing Alhambra Cigar and Cigarette Manufacturing Co. v. CIR (GR No. L- 12026, 29 May 1959), the Supreme Court stated that: whenever a controversy arises on the deductibility, for purposes of income tax, of certain items for alleged compensation of officers of the taxpayer, two (2) questions become material, Aguinaldo Industries Corporation (AIC) is a domestic corporation engaged in the manufacture of fishing nets, a tax-exempt industry and the manufacture of furniture. For accounting purposes, each division is provided with separate books of accounts. Previously, AIC acquired a parcel of land in Muntinlupa, Rizal, as site of the fishing net factory. Later, it sold the Muntinlupa property. AIC derived profit from this sale which was entered in the books of the Fish Nets Division as miscellaneous income to distinguish it from its tax-exempt income. For the year 1957, AIC filed two separate income tax returns for each division. After investigation, the examiners of the BIR found that the Fish Nets Division deducted from its gross income for that year the amount of P61,187.48 as additional remuneration paid to the officers of AIC. This amount was taken from the net profit of an isolated transaction (sale of Muntinlupa land) not in the course of or carrying on of AIC's trade or business, and was reported as part of the selling expenses of

namely: (a) Have personal services been actually rendered by said officers? (b) In the affirmative case, what is the reasonable allowance therefor? Here, no evidence was presented to show that the corporate officers who received bonuses had a hand in the sale transaction of the Muntinglupa property [which could be the basis of a grant to them of the bonuses out of the profit derived from the sale]. Thus, the amount representing the bonuses could not be allowed as a deductible business expense. This posture is in line with the doctrine in the law of taxation that the taxpayer must show that its claimed deductions clearly come within the language of the law since allowances, like exemptions, are matters of legislative grace. CIR v. General Foods (Phils.), Inc., GR No. 143672, 24 April 2003 Q: In general, what is the treatment accorded to deductions from gross income? To be deductible from gross income, an advertising expense must comply with the following requirements: (1) the expense must be ordinary and necessary; (2) it must have been paid or incurred during the taxable year; (3) it must have been paid or incurred in carrying on the trade or business of the taxpayer; and (4) it must be supported by receipts, records or other pertinent papers. In CIR v. General Foods (Phils.), Inc., respondent filed its income tax return for 1985, claiming a certain amount as deductible

the Muntinlupa land. Upon recommendation of the examiner that the said sum of P61,187.48 be disallowed as deduction from gross income, petitioner asserted in its letter of February 19, 1958, that said amount should be allowed as deduction because it was paid to its officers as allowance or bonus pursuant to its by-laws.

Respondent corporation General Foods (Phils), which is engaged in the manufacture of Tang, Calumet and Kool-Aid, filed its income tax return for the fiscal year ending February 1985 and claimed as deduction, among other business expenses, P9,461,246 for media advertising for Tang. The Commissioner disallowed 50% of the deduction claimed and assessed deficiency income taxes of P2,635,141.42 against General Foods, prompting the latter to file an MR which was denied. General Foods later on filed a petition for review at CA, which reversed and set aside an earlier decision by CTA dismissing the companys appeal.

media advertising expense for the product Tang. Respondent and the CIR were in agreement that the subject advertising expense was paid or incurred within the relevant taxable year and was incurred in carrying on a trade or business. Hence, it was necessary. However, as to whether it was ordinary, their views were in conflict. The CIR maintained that the subject advertising expense was not ordinary for failure to comply with two requirements set by US jurisprudence: (1) the amount incurred must be reasonable, and (2) the amount incurred must not be a capital outlay to create goodwill for the product and/or the corporations business. *Otherwise, the expense must be considered a capital expenditure to be spread out over a reasonable time.] There is yet to be a clear-cut criteria or fixed test for determining the reasonableness of an advertising expense. There being no hard and fast rule on the matter, the right to a deduction depends on a number of factors such as but not limited to: the type and size of business in which the taxpayer is engaged; the volume and amount of its net earnings; the nature of the expenditure itself; the intention of the taxpayer and the general economic conditions. It is the interplay of these, among other factors and properly weighted, that will yield a proper evaluation. Here, the Supreme Court held that the advertising expense for a single product (Tang) was inordinately large. Even if it was necessary, it could not be considered an ordinary expense. In order to be

Philex Mining Corporation v. CIR, GR No. 148187, 16 April 2008

deductible, a business expense must be both ordinary and necessary. Deductions for income tax purposes partake the nature of tax exemptions; hence, if tax exemptions are strictly construed, then deductions must also be strictly construed [against the taxpayer and liberally in favor of the taxing authority]. Q: In general, what is the treatment accorded to deductions from gross income? In Philex Mining Corporation v. CIR, petitioner entered into an agreement with Baguio Gold Mining Company for the former to manage and operate the latters mining claim in the Benguet Province. The agreement was denominated as Power of Attorney. In the course of managing and operating the project, petitioner made advances of cash and property to Baguio Gold. However, the mine suffered continuing losses over the years which resulted to petitioners withdrawal as manager of the mine and in the eventual cessation of mine operations. In its 1982 income tax return, petitioner deducted from its gross income a sum representing loss on settlement of receivables from Baguio Gold against reserves and allowances. The CIR disallowed the amount as deductible bad debt and assessed petitioner a deficiency income tax. The Supreme Court found that petitioners advances were investments in a partnership known as the Sto. Nio Mine. The advances were not debts of Baguio Gold to petitioner inasmuch as the latter was under no unconditional obligation to return the same to

Philex Mining entered into a management agreement with Baguio Gold. The parties' agreement was denominated as "Power of Attorney" which provided among others: a. Funds available for Philex Mining during the management agreement; and b. Compensation to Philex Mining which shall be fifty per cent (50%) of the net profit; In the course of managing and operating the project, Philex Mining made advances of cash and property in accordance with the agreement. However, the mine suffered continuing losses over the years which resulted to petitioner's withdrawal as manager and cessation of mine operations. The parties executed a "Compromise with Dation in Payment" wherein Baguio Gold admitted an indebtedness to Philex Mining, which was subsequently amended to include additional obligations. Subsequently, Philex Mining wrote off in its 1982 books of account the remaining outstanding indebtedness of Baguio Gold by charging P112,136,000.00 to allowances and reserves that were set up in 1981 and P2,860,768.00 to the 1982 operations.

Atlas Consolidated Mining & Development Corporation v. CIR, GR Nos. L-26911 and L26924, 27 January 1981

the former under the Power of Attorney. Petitioner failed to substantiate its assertion that the advances were subsisting debts of Baguio Gold that could be deducted from its gross income. Deductions for income tax purposes partake of the nature of tax exemptions and are strictly construed against the taxpayer, who must prove by convincing evidence that he is entitled to the deduction claimed. Q: What are the general requisites for deductibility of business expense?

In its 1982 annual income tax return, Philex Mining deducted from its gross income the amount of P112,136,000.00 as "loss on settlement of receivables from Baguio Gold against reserves and allowances." However, BIR disallowed the amount as deduction for bad debt and assessed petitioner a deficiency income tax of P62,811,161.39.

Atlas is a corporation engaged in the mining industry registered. On August 1962, CIR assessed against Atlas for deficiency income taxes for the years 1957 and 1958. For the In Atlas Consolidated Mining & Development Corporation v. CIR, one question was: were the year 1957, it was the opinion of the CIR that Atlas is not entitled to exemption from the expenses paid by Atlas for the services income tax under RA 909 because same covers rendered by a public relations firm, P.K. MacKer & Co., labeled as stockholders relation only gold mines. For the year 1958, the deficiency income tax covers the disallowance service fee considered deductible business of items claimed by Atlas as deductible from expense? The expense in question was gross income. Atlas protested for incurred to create a favorable image of the reconsideration and cancellation, thus the CIR corporation in order to gain or maintain the conducted a reinvestigation of the case. patronage of its stockholders and the public. On October 1962, the Secretary of Finance The Supreme Court held that such expense ruled that the exemption provided in RA 909 was not an ordinary and necessary expense allowed to be deducted from the corporations embraces all new mines and old mines whether gold or other minerals. Accordingly, gross income. the CIR recomputed Atlas deficiency income In order to be deductible as a business tax liabilities in the light of said ruling. On June expense, three conditions must concur 1964, the CIR issued a revised assessment [business test]: (1) the expense must be entirely eliminating the assessment for the ordinary and necessary; (2) it must be paid or year 1957. The assessment for 1958 was incurred within the taxable year; and (3) it must be paid or incurred in carrying on a trade reduced from which Atlas appealed to the CTA, assailing the disallowance of the or business. Additionally, the taxpayer must substantially prove by evidence or records the following items claimed as deductible from its gross income for 1958: Transfer agent's fee, deductions claimed under the law.

Esso Standard Eastern, Inc. v. CIR, GR Nos. 28508-9, 7 July 1989

There is no hard and fast rule on the matter. The right to a deduction depends in each case on the particular facts and the relation of the payment to the type of business in which the taxpayer is engaged. The intention of the taxpayer often may be the controlling fact in making the determination. Assuming that the expenditure is ordinary and necessary in the operation of the taxpayers business, the answer to the question as to whether the expenditure is an allowable deduction as a business expense must be determined from the nature of the expenditure itself, which in turn depends on the extent and permanency of the work accomplished by the expenditure. In all events, however, the taxpayer must establish a logical link between the expense and the taxpayers business. The Supreme Court eventually held that the expense incurred by Atlas was not a deductible business expense, but a capital expenditure. Q: What are the general requisites for deductibility of business expense? At issue in Esso Standard Eastern, Inc. v. CIR was the classification of the margin fees paid by ESSO to the Central Bank on its profit remittances to its New York head office in the taxable years 1959 and 1960. ESSO sought the refund of the amount it paid as margin fees contending that these fees were deductible from gross income either as a tax or as an ordinary and necessary business expense. The Supreme Court held that the margin fees were not taxes, as they were imposed by the State in the exercise of its police power and not the

Stockholders relation service fee, U.S. stock listing expenses, Suit expenses, and Provision for contingencies. The CTA allowed said items as deduction except those denominated by Atlas as stockholders relation service fee and suit expenses. Both parties appealed the CTA decision to the SC by way of two (2) separate petitions for review. Atlas appealed only the disallowance of the deduction from gross income of the socalled stockholders relation service fee.

ESSO deducted from its gross income, as part of its ordinary and necessary business expenses, the amount it had spent for drilling and exploration of its petroleum concessions. This claim was disallowed by the CIR on the ground that the expenses should be capitalized and might be written off as a loss only when a "dry hole" should result. ESSO then filed an amended return and claimed as ordinary and necessary expenses margin fees it had paid to the Central Bank on its profit remittances to its New York head office. The CIR disallowed the claimed deduction for the margin fees paid. CIR

Hospital de San Juan de Dios, Inc. v. CIR, GR No. 31305, 10 May 1990

power of taxation. The margin fees were an exaction designed to curb the excessive demands upon the countrys international reserve. The High Court also stated that the margin fees were not an ordinary and necessary business expense, because ESSO had not shown that the remittance to the head office of part of its profits was made in furtherance of its own trade or business. If at all, the margin fees were incurred for purposes proper to the conduct of the corporate affairs of Standard Vacuum Oil Company in New York, but certainly not in the Philippines. Q: What are the general requisites for deductibility of business expense?

assessed ESSO a deficiency income tax which arose from the disallowance of the margin fees. ESSO paid under protest and claimed for a refund. CIR denied the claims for refund, holding that the margin fees paid to the Central Bank could not be considered taxes or allowed as deductible business expenses.

In a letter dated January 15, 1959, the Commissioner of Internal Revenue assessed and demanded from the petitioner, Hospital De San Juan De Dios, Inc., payment of P51,462 In Hospital de San Juan de Dios, Inc. v. CIR, as deficiency income taxes for 1952 to 1955. petitioner was a charitable, non-stock nonThe petitioner protested against the profit corporation which was engaged in both taxable and non-taxable operations. Its income assessment and requested the Commissioner to cancel and withdraw it. After reviewing the included rentals, interests and dividends assessment, the Commissioner advised received from its properties and investments. petitioner on November 8, 1960 that the In the computation of its taxable income for deficiency income tax assessment against it the years 1952 to 1955, petitioner allowed all its taxable income to share in the allocation of was reduced to only P16,852.41. Still the petitioner, through its auditors, insisted on the administrative expenses. The CIR, however, cancellation of the revised assessment. The disallowed the interests and dividends from request was, however, denied. sharing in the allocation of administrative On September 18, 1965, petitioner sought a expenses on the ground that the expenses incurred in the administration or management review of the assessment by the CTA. In a of petitioners investments were not allowable decision dated August 29, 1969, the CTA business expenses inasmuch as they were not upheld the Commissioner. It held that the expenses incurred by the petitioner for incurred in carrying on any trade or handling its funds or income consisting solely business. The Supreme Court held that as of dividends and interests, were not expenses the principle of allocating expenses is incurred in "carrying on any trade or grounded on the premise that the taxable

income was derived from carrying on a trade or business, as distinguished from mere receipt of interests and dividends from ones investments, the Court of Tax Appeals correctly ruled that said income should not share in the allocation of administrative expenses. Otherwise stated, the expenses incurred in the administration or management of petitioners investments, i.e., interests and dividends, were not deductible business expenses. C.M. Hoskins & Co., Inc. v. CIR, GR No. L24059, 28 November 1969

business," hence, not deductible as business or administrative expenses. Petitioner filed a motion for reconsideration of the CTA decision. When its motion was denied, it filed this petition for review.

Q: Compensation for personal services actually Petitioner, a domestic corporation engaged in the real estate business as brokers, managing rendered; illustrative cases. agents and administrators, filed its income tax return for its fiscal year ending September 30, In C.M. Hoskins & Co., Inc. v. CIR, petitioner 1957 showing a net income of P92,540.25 and filed its income tax return for the year 1957. a tax liability due thereon of P18,508.00, The CIR disallowed as deductible business which it paid in due course. Upon verification expense a certain sum representing of its return, CIR, disallowed four items of supervision fee paid to its controlling deduction in petitioner's tax returns and stockholder, Hoskins. Considering the assessed against it an income tax deficiency in circumstances (e.g., Hoskins almost wholly the amount of P28,054.00 plus interests. The owning and controlling petitioner), the Supreme Court found that the supervision fee Court of Tax Appeals upon reviewing the assessment at the taxpayer's petition, upheld paid to Hoskins was inordinately large, and respondent's disallowance of the principal could not be accorded the treatment of item of petitioner's having paid to Mr. C. M. ordinary and necessary expenses allowed as Hoskins, its founder and controlling deductible items. [It was treated as a stockholder the amount of P99,977.91 distribution of earnings and profits of representing 50% of supervision fees earned petitioner.] The Court explained the test of by it and set aside respondent's disallowance reasonableness, citing in the process the case of three other minor items. of Kuenzle & Streiff, Inc. v. CIR (28 SCRA 366, 29 May 1969), to wit: The conditions Petitioner questions in this appeal the Tax precedent to the deduction of bonuses to Court's findings that the disallowed payment employees are: (1) the payment of the bonuses is in fact compensation; (2) it must be to Hoskins was an inordinately large one,

Aguinaldo Industries Corporation v. CIR, GR No. L-29790, 25 February 1982

for personal services actually rendered; and (3) the bonuses, when added to the salaries, are reasonable x x x when measured by the amount and quality of the services performed with relation to the business of the particular taxpayer. Of course, *t+here is no fixed test for determining the reasonableness of a given bonus as compensation. This depends upon many factors, one of them being the amount and quality of the services performed with relation to the business. Other tests suggested are: payment must be made in good faith; the character of the taxpayers business, the volume and amount of its net earnings, its locality, the type and extent of the services rendered, the salary policy of the corporation; the size of the particular business; the employees qualifications and contributions to the business venture; and general economic conditions. Finally, the right of an employer to fix the compensation of its officers and employees is recognized, but for income tax purposes the employer cannot legally claim such bonuses as deductible expenses unless they are shown to be reasonable. To hold otherwise would open the gate of rampant tax evasion. Q: Compensation for personal services actually rendered; illustrative cases. In Aguinaldo Industries Corporation v. CIR, when petitioner sold its property in Muntinglupa, the corporate officers of petitioner were given bonuses. The amount representing these bonuses was claimed by

which bore a close relationship to the recipient's dominant stockholdings and therefore amounted in law to a distribution of its earnings and profits.

Aguinaldo Industries Corporation (AIC) is a domestic corporation engaged in the manufacture of fishing nets, a tax-exempt industry and the manufacture of furniture. For accounting purposes, each division is provided with separate books of accounts. Previously, AIC acquired a parcel of land in Muntinlupa, Rizal, as site of the fishing net factory. Later, it

CIR v. Algue, Inc., GR No. L-28896, 17 February 1988

petitioner as a deductible business expense. The Supreme Court held that the bonuses could not be deemed a deductible expense for tax purposes, even if the aforesaid sale could be considered as a transaction for carrying on the trade or business of the petitioner and the grant of the bonus to the corporate officers pursuant to petitioners by-laws could, as an intra-corporate matter, be sustained. Citing Alhambra Cigar and Cigarette Manufacturing Co. v. CIR (GR No. L- 12026, 29 May 1959), the Supreme Court stated that: whenever a controversy arises on the deductibility, for purposes of income tax, of certain items for alleged compensation of officers of the taxpayer, two (2) questions become material, namely: (a) Have personal services been actually rendered by said officers? (b) In the affirmative case, what is the reasonable allowance therefor? Here, no evidence was presented to show that the corporate officers who received bonuses had a hand in the sale transaction of the Muntinglupa property [which could be the basis of a grant to them of the bonuses out of the profit derived from the sale]. Thus, the amount representing the bonuses could not be allowed as a deductible business expense Q: Compensation for personal services actually rendered; illustrative cases. In CIR v. Algue, Inc., for the years 1958 and 1959 respondent sought to claim as deductible business expense the sum of Php 75,000 as promotional fees. Respondent was a family corporation appointed by the Philippine Sugar

sold the Muntinlupa property. AIC derived profit from this sale which was entered in the books of the Fish Nets Division as miscellaneous income to distinguish it from its tax-exempt income. For the year 1957, AIC filed two separate income tax returns for each division. After investigation, the examiners of the BIR found that the Fish Nets Division deducted from its gross income for that year the amount of P61,187.48 as additional remuneration paid to the officers of AIC. This amount was taken from the net profit of an isolated transaction (sale of Muntinlupa land) not in the course of or carrying on of AIC's trade or business, and was reported as part of the selling expenses of the Muntinlupa land. Upon recommendation of the examiner that the said sum of P61,187.48 be disallowed as deduction from gross income, petitioner asserted in its letter of February 19, 1958, that said amount should be allowed as deduction because it was paid to its officers as allowance or bonus pursuant to its by-laws.

Algue Inc. is a domestic corporation engaged in engineering and construction. The corporation was appointed by the Philippine Sugar Estate Development Company (PSEDC) as its agent, authorizing Algue to sell the latters land, factories and oil manufacturing process. Pursuant to this, a certain Guevara and others worked for the formation of the

3M Philippines, Inc. v. CIR, GR No. L-82833, 26 September 1988

Estate Development Company as its agent and pursuant to such authority, several employees of respondent worked for the formation of the Vegetable Oil Investment Corporation, inducing others to invest in it. The compensation that these employees received formed part of the promotional fees. The CIR argued that these payments were fictitious because most of the payees were members of the same family in control of respondent. The CIR suggested a tax dodge, i.e., an attempt to evade a legitimate assessment by involving an imaginary deduction. The Supreme Court found for respondent. The burden is on the taxpayer to prove the validity of the claimed deduction. The Court held that in the present case, that onus was discharged satisfactorily. Because respondent was a family corporation, strict business procedures did not apply to it. Moreover, payment of the promotional fees was necessary and reasonable in the light of the efforts exerted by the payees in inducing investors and prominent businessmen to venture in an experimental enterprise and involve themselves in a new business requiring millions of pesos. Q: Rentals and other payments; illustrative case In 3M Philippines, Inc. v. CIR, 3M Phils. was a subsidiary of 3M US. The parties entered into agreements under which 3M Phils. agreed to pay to 3M US a 3% technical service fee and a royalty of 2% of its net sales. In its income tax return for 1974, 3M Phils. claimed Php 3 million as deductible business expense,

Vegetable Oil Investment Corporating, incuding others to invest. This corporation purchased the PSEDC properties. For this sale, Algue received a commission of 125K and 75K was paid as promotional fees to the five individuals led by Guevara. CIR sent Algue a letter assessing it for delinquent income taxes. Algue claims the 75k was deductible as a necessary business expense,. On the other hand, the CIR contends otherwise and claimed that these payments are fictitious because most of the payees (the five individuals) are members of the same family in control of Algue.

3M Philippines, Inc. is a subsidiary of the Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company (or "3M-St. Paul") a non-resident foreign corporation with principal office in St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S.A. It is the exclusive importer, manufacturer, wholesaler, and distributor in the Philippines of all products of 3M-St. Paul. To enable it to manufacture, package, promote, market, sell and install the highly specialized products of its parent

particularly, as royalties and technical service fees. The CIR allowed a deduction only of an amount representing royalties and technical service fees for locally manufactured products. The CIR disallowed the deduction of the amount representing royalties and technical service fees for finished products imported by 3M Phils. from 3M US. The CIR based its decision on CB Circular No. 393 (Regulations Governing Royalties/Rentals) dated 7 December 1973 partly providing that royalties should be paid only on commodities manufactured by the licensee under the royalty agreement. [No royalty was payable on the wholesale price of finished products imported by the licensee from the licensor.] The Supreme Court upheld the CIRs argument and ruled thus: although the Tax Code allows payments of royalty to be deducted from gross income as business expenses, it is CB Circular No. 393 that defines what royalty payments are proper. Hence, improper payments of royalty are not deductible as legitimate business expenses.

company, and render the necessary post-sales service and maintenance to its customers, 3M Phils. entered into a "Service Information and Technical Assistance Agreement" and a "Patent and Trademark License Agreement" with the latter under which the 3m Phils. agreed to pay to 3M-St. Paul a technical service fee of 3% and a royalty of 2% of its net sales. Both agreements were submitted to, and approved by, the Central Bank of the Philippines. the petitioner claimed the following deductions as business expenses: (a) royalties and technical service fees of P 3,050,646.00; and (b) pre-operational cost of tape coater of P97,485.08. As to (a), the Commissioner of Internal Revenue allowed a deduction of P797,046.09 only as technical service fee and royalty for locally manufactured products, but disallowed the sum of P2,323,599.02 alleged to have been paid by the petitioner to 3M-St. Paul as technical service fee and royalty on P46,471,998.00 worth of finished products imported by the petitioner from the parent company, on the ground that the fee and royalty should be based only on locally manufactured goods. While as to (b), the CIR only allowed P19,544.77 or one-fifth (1/5) of 3M Phils.capital expenditure of P97,046.09 for its tape coater which was installed in 1973 because such expenditure should be amortized for a period of five (5) years, hence, payment of the disallowed balance of P77,740.38 should be spread over the next four (4) years. The CIR ordered 3M Phil. to pay

P840,540 as deficiency income tax on its 1974 return, plus P353,026.80 as 14% interest per annum from February 15, 1975 to February 15, 1976, or a total of P1,193,566.80. 3M Phils. protested the CIRs assessment but it did not answer the protest, instead issuing a warrant of levy. The CTA affirmed the assessment on appeal. Roxas v. Court of Tax Appeals, GR No. L-25043, Q: Entertainment, amusement and recreation Don Pedro Roxas and Dona Carmen Ayala, 26 April 1968 Spanish subjects, transmitted to their expense; illustrative cases. grandchildren by hereditary succession In Roxas v. Court of Tax Appeals, the late Roxas agricultural lands in Batangas, a residential house and lot in Manila, and shares of stocks Spouses bequeathed several properties to in different corporations. To manage the their grandchildren. To manage said properties, said children, namely, Antonio, properties, a partnership called Roxas y Cia was formed. For the years 1953 and 1955, the Eduardo and Jose Roxas formed a partnership called Roxas y Compania. CIR disallowed deductions from gross income On June 1958, the CIR assessed deficiency of various business expenses of Roxas y Cia. income taxes against the Roxas Brothers for The business expenses comprised of Php 40 the years 1953 and 1955. Part of the for tickets to a banquet given in honor of Sergio Osmea and Ph 28 for San Miguel beer deficiency income taxes resulted from the disallowance of deductions from gross income given as gifts to various persons. These of various business expenses and deductions were claimed as representation contributions claimed by Roxas. (see expense expenses. The Supreme Court found that no items below) evidence was shown to link the expenses to The Roxas brothers protested the assessment the business of Roxas y Cia. Hence, according but inasmuch as said protest was denied, they to the Court, such deductions were correctly instituted an appeal in the CTA, which disallowed by the CIR. Representation expenses are deductible from sustained the assessment except the demand for the payment of the fixed tax on dealer of gross income as expenditures incurred in securities and the disallowance of the carrying on a trade or business under [now deductions for contributions to the Philippine Section 34(A) of the 1997 Tax Code] provided Air Force Chapel and Hijas de Jesus' Retiro de the taxpayer proves that they are reasonable Manresa. Not satisfied, Roxas brothers in amount, ordinary and necessary, and appealed to the SC. The CIR did not appeal. incurred in connection with his business. Revenue Regulations No. 10-2001, 10 July Q: Entertainment, amusement and recreation

2002

expense; illustrative cases. Revenue Regulations No. 10-2002 enumerates the requisites for the deductibility of entertainment, amusement and recreation expense as follows: (1) it must be paid or incurred during the taxable year; (2) it must be directly connected to the development, management and operation of the trade, business or profession of the taxpayer, OR directly related to or in furtherance of the conduct of his/its trade, business or exercise of a profession; (3) it must not be contrary to law, morals, good customs, public policy or public order; (4) it must not have been paid, directly or indirectly, to any person as a bribe, kickback or other similar payment; (5) it must be duly substantiated by adequate proof; and the appropriate amount of withholding tax, if applicable, should have been withheld therefrom and paid to the BIR Q: Make a distinction between business expense and capital expenditure How does one classify expenses incurred on property? In CIR v. A. Soriano y Cia, respondent owned a parcel of land in Intramuros, which it later sold to J.M. Tuason & Co. In computing the income tax due, was respondent allowed to include as cost of the property the expenditures it incurred in

CIR v. A. Soriano y Cia, GR No. L-24893, 26 March 1971

A. Soriano y Cia owned a piece of land located in Intramuros, City of Manila, on which it proposed to construct an office building. To carry out the project it had the necessary plans drawn in 1960 by Architect J. M. Zaragoza, and entered into a pile-driving contract that same year with the construction firm of A. M. Oreta & Co. The pile-driving was actually done in 1960. After these preparations and before the

improving said property (e.g., pile-driving service fee and architects fee)? The Supreme Court said that: expenditures for replacements, alterations, improvements or additions which either prolong the life of the property or increase its value are capital in nature. The expenses incurred by respondent increased the value of the Intramuros property and hence, must be considered as capital expenditures that formed part of the cost of the property [which amount was relevant in computing the income tax due].

construction of the building, the Taxpayer sold the property to J. M. Tuason & Co. The balance of P49,329.55 due on the Contractor's fees, including the cost of testing timber piles in the amount of P4,000.00, was paid only on June 16, 1961 after the Contractor had concluded negotiations with the City Engineer of Manila for the settlement of the problem brought by J. M. Tuason & Co. and after said Contractor had secured a certification by the Office of the City Engineer of Manila in connection therewith. It also appears that in the year 1961, the Taxpayer completed payment to the architect, Mr. Zaragoza, of the latter's fees for services rendered, the same consisting of the unpaid balance of P10,000.00, plus P1,000.00 reimbursement for disbursements made by the latter in connection with the Intramuros property. On April 17, 1961, the Taxpayer filed its 1960 Income Tax Return and in due time paid the income tax due. On October 4, 1961, it filed an amended Income Tax Return for the year 1960 showing a refundable amount of P15,099.00 due to the inclusion of expenses paid on June 1 and June 16, 1961 amounting to P50,329.55, expenses allegedly incurred for pile-driving and architect's fees which the Taxpayer claimed were part of the cost of its Intramuros property sold. On the same day, a request for the refund of the said amount was filed. Again, on March 12, 1963, the Taxpayer filed a second amended return showing this time a refundable amount of P18,099.00 based on expenses already included in the previous

Atlas Consolidated Mining & Development Corporation v. CIR, GR Nos. L-26911 and L26924, 27 January 1981

amended Income Tax Return, plus another item of expense in the amount of P10,000.00 paid as architect's fees on March 15, 1961, upon the claim that all said expenses formed part of the cost of the Intramuros property aforesaid. A request for the refund of the total amount of P18,099.00 was also made. Atlas is a corporation engaged in the mining Q: Make a distinction between business industry registered. On August 1962, CIR expense and capital expenditure assessed against Atlas for deficiency income In Atlas Consolidated Mining & Development taxes for the years 1957 and 1958. For the Corporation v. CIR, one question was: were the year 1957, it was the opinion of the CIR that expenses paid by Atlas for the services Atlas is not entitled to exemption from the rendered by a public relations firm, P.K. income tax under RA 909 because same covers MacKer & Co., labeled as stockholders relation only gold mines. For the year 1958, the service fee considered deductible business deficiency income tax covers the disallowance expense? The expense in question was of items claimed by Atlas as deductible from incurred to create a favorable image of the gross income. Atlas protested for corporation in order to gain or maintain the reconsideration and cancellation, thus the CIR patronage of its stockholders and the public. conducted a reinvestigation of the case. The Supreme Court held that such expense On October 1962, the Secretary of Finance was not an ordinary and necessary expense ruled that the exemption provided in RA 909 allowed to be deducted from the corporations embraces all new mines and old mines gross income. whether gold or other minerals. Accordingly, In order to be deductible as a business the CIR recomputed Atlas deficiency income expense, three conditions must concur tax liabilities in the light of said ruling. On June [business test]: (1) the expense must be 1964, the CIR issued a revised assessment entirely eliminating the assessment for the ordinary and necessary; (2) it must be paid or incurred within the taxable year; and (3) it year 1957. The assessment for 1958 was must be paid or incurred in carrying on a trade reduced from which Atlas appealed to the or business. Additionally, the taxpayer must CTA, assailing the disallowance of the substantially prove by evidence or records the following items claimed as deductible from its deductions claimed under the law. gross income for 1958: Transfer agent's fee, The Supreme Court eventually held that the Stockholders relation service fee, U.S. stock expense incurred by Atlas was not a deductible listing expenses, Suit expenses, and Provision business expense, but a capital expenditure. for contingencies. The CTA allowed said items

CIR v. General Foods (Phils.), Inc., GR No. 143672, 24 April 2003

The expense incurred to create a favorable image of the corporation in order to gain or maintain the patronage of it stockholders and the public, similar to expenses relating to recapitalization and reorganization of the corporation, the cost of obtaining stock subscription, promotion and commission or fees paid for the sale of stock reorganization are capital expenditures which should be spread out over a reasonable period of time. Q: Make a distinction between business expense and capital expenditure To be deductible from gross income, an advertising expense must comply with the following requirements: (1) the expense must be ordinary and necessary; (2) it must have been paid or incurred during the taxable year; (3) it must have been paid or incurred in carrying on the trade or business of the taxpayer; and (4) it must be supported by receipts, records or other pertinent papers. In CIR v. General Foods (Phils.), Inc., respondent filed its income tax return for 1985, claiming a certain amount as deductible media advertising expense for the product Tang. Respondent and the CIR were in agreement that the subject advertising expense was paid or incurred within the relevant taxable year and was incurred in carrying on a trade or business. Hence, it was necessary. However, as to whether it was

as deduction except those denominated by Atlas as stockholders relation service fee and suit expenses. Both parties appealed the CTA decision to the SC by way of two (2) separate petitions for review. Atlas appealed only the disallowance of the deduction from gross income of the socalled stockholders relation service fee.

Commissioner disallowed 50% of the deduction claimed and assessed deficiency income taxes of P2,635,141.42 against General Foods, prompting the latter to file an MR which was denied. General Foods later on filed a petition for review at CA, which reversed and set aside an earlier decision by CTA dismissing the companys appeal.

ordinary, their views were in conflict. The CIR maintained that the subject advertising expense was not ordinary for failure to comply with two requirements set by US jurisprudence: (1) the amount incurred must be reasonable, and (2) the amount incurred must not be a capital outlay to create goodwill for the product and/or the corporations business. *Otherwise, the expense must be considered a capital expenditure to be spread out over a reasonable time.] There is yet to be a clear-cut criteria or fixed test for determining the reasonableness of an advertising expense. There being no hard and fast rule on the matter, the right to a deduction depends on a number of factors such as but not limited to: the type and size of business in which the taxpayer is engaged; the volume and amount of its net earnings; the nature of the expenditure itself; the intention of the taxpayer and the general economic conditions. It is the interplay of these, among other factors and properly weighted, that will yield a proper evaluation. Here, the Supreme Court held that the advertising expense for a single product (Tang) was inordinately large. Even if it was necessary, it could not be considered an ordinary expense. In order to be deductible, a business expense must be both ordinary and necessary. The Supreme Court also found that the subject advertising expense was a capital expenditure which should be spread out over a reasonable period of time. Advertising is generally of two kinds: (1)

CIR v. Prieto, GR No. L-13912, 30 September 1960

advertising to stimulate the current sale of merchandise or use of services and (2) advertising designed to stimulate the future sale of merchandise or use of services. The second type involves expenditures incurred, in whole or in part, to create or maintain some form of goodwill for the taxpayers trade or business or for the industry or profession which the taxpayer is a member [or as in the present case, for the protection of brand franchise]. If the expenditures are for the advertising of the first kind, then, except as to the question of the reasonableness of amount, there is no doubt such expenditures are deductible as business expenses. If, however, the expenditures are for advertising of the second kind, then normally they should be spread out over a reasonable period of time. Q: Interest on indebtedness is an allowable deduction from gross income. How about interest on taxes?