Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ethnography Final Draft

Uploaded by

api-251527289Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ethnography Final Draft

Uploaded by

api-251527289Copyright:

Available Formats

Shounak Dattagupta English 106 M.

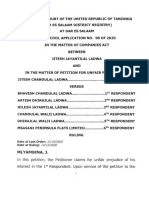

Parsons April 7, 2014 Ethnography: A Study of the Chamber Community of Northwood A large man eyed a room of quiet people. Trophies and pictures of generations gone by lined every available square inch of the wall everywhere around us. Phrases from Aristotle hung above the mans head; libraries of written music lay hidden neatly behind a very messy white board. He opened his mouth, and spoke. Ive got some good news, and bad news. The good news is, this year, Northwood has been honored with a fifth Grammy award, he paused, smiled, guess I should probably think about retiring. I mean, how much higher can you guys possibly climb? This was met with cheers, scattered applause, and laughter. The man cleared his throat. The bad news is Shounaks back. And immediately my world exploded with hugs, kisses and handshakes. Halop smiled down on me from his pedestal; I was home in my discourse community. A discourse communitys primary objective is solidarity and promotion of its chosen form; that is, the members of this highly exclusive community may individually differ in terms of background, features, and experiences, but their ambitions and intentions are aligned in a single purpose. John Swales, a renowned linguist and expert on genre analysis, developed a set of six comprehensive criteria to define a discourse community; in the following analysis, I will attempt to prove that the Chamber Choral Program community of Northwood High School is a discourse community according to the criteria of John Swales.

Swales first criteria states that a discourse community has a broadly agreed upon set of goals (Swales 471). The Chamber community of Northwood, (indeed, the choral music community as a whole), perfectly fits this description. According to Dalton Tran, current tenor section leader of the Chamber group of Northwood, the [entire] point of musical communities is to make good music (Tran, interview). That is, our goal is to cast aside our differences in race, gender, intelligence, height, attractiveness, and so on (everything unnecessary to make music, really), in order to allow solidarity in a common sensation; that is, we cast everything aside while singing so that we can, however briefly, feel each other in the music we are making. This goal is both broadly agreed upon and fervently, passionately pursued by the Chamber community of Northwood. At the same time, however, it is interesting to note that the same differences that we do not allow to limit us while making music also ensures that the music we produce is diverse; choral music in its purest form is a unique combination of different voices, voices that reflect different timbres according to the experiences and life of its owner. As a result, each voice adds a different emotion, a different interpretation of life, a different hue to the melting pot. Therefore, the goal is not only pursued broadly, but also uniquely; no two sessions of choral music is ever the same for the above reason. Swales second criteria states that the community must have mechanisms of intercommunication among its members (Swales 471). This section of the analysis will be fairly brief; in the case of the Chamber community, there is no reliance on emails, Facebook, or any other nonpersonal social media. Our intercommunication is done purely through person-to-person interaction; this is possible solely because of the unshakeable unity and closeness of the entire community. When considering this second criteria, there are two forms of intercommunication that come to mind; that of professional, tutorial intercommunication (an instructor or director teaching us something)

and that of student-to-student communication (a piece of news, or something more trivial). The former form is accomplished easily during our class time, when the Chamber community gathers together to rehearse as a group. Our director, Mr. Halop, informs us of our current agenda, rejoices in our recent accomplishments, cracks some jokes about the misery and joy of life, and then promptly urges us to get down to business. In this way, intercommunication is effectively achieved. On the other hand, if someone must contact an individual not currently in the room, he or she need simply voice their need to the community (or just a member of the community he or she trusts, if the news is of a gossipy or otherwise private nature), and the message will eventually be delivered to its intended audience. As Mr. Tran states, in this room, we arent simply colleagues, but brothers and sisters. There really isnt any need to be secretive or shy about anything; we share each others triumphs and sorrows. Thats why, when I hear Matt or Eileen singing next to me, I can feel them better since I know whats up with their lives. This is what helps us communicate and make good music (Tran). Swales third criteria states that the community uses its participatory mechanisms primarily to provide information and feedback (Swales 471). Obviously, I and my peers are the participatory mechanisms in Chamber, since we are the ones who, collectively, carry the title of Chamber. Furthermore, we participatory mechanisms criticize and encourage each other in our music-making; for example, Dalton points out to me that I didnt properly observe the quarter rest before hitting the high C in the third bar. I profusely thanks Dalton for his sharp ear, and promise to amend the mistake. Dalton and I, therefore, are participatory mechanisms of the Chamber community who have provided information and feedback on a matter relevant to the community; as a result, the communitys solidarity has been strengthened and the pursuit of its common goal has been renewed with fresh vigor. Furthermore, although the Shounak-Dalton interaction was between only two members of the group, our exchange reinforced the performance of the group as a whole. Therefore, as long as I remember to

observe the quarter rest next time, the Chamber community as a whole is one quarter rest closer to reaching its goal of making soulful and gorgeous music. Swales fourth criteria states that the community must utilize and possess one or more genres in the communicative furtherance of its aims (Swales 471). In the case of the Chamber community, this is our daily set of vocal warm-ups. The warm-ups are designed not just for our throats, but for our bodies as a whole; it involves a series of techniques intended to relax our abdominal and back muscles, increase our lung capacity, and lift our soft palette. In addition to these exercises, we perform some light cardio simply to get our blood flowing and adrenaline pumping, which is especially helpful when rehearsing pieces that require a somewhat harsh color. We do all this for one obvious goal; to ensure that, individually, we perform at our maximum capability and, as a community, make the best music we possibly can. Swales fifth criteria states that the community must acquire some specific lexis (Swales 471). The lexis of the Chamber community of Northwood is shared by only those who understand and appreciate the simultaneously complex and simple beauty of vocal music, and those who have been specifically accepted as part of the group. The reason; anyone who is not accustomed to the mannerisms and nuances of the Chamber community, such as the sarcastic and witty nature of its director, the jargon being thrown around constantly, the sometimes playful, sometimes dead serious nature of its members, would feel utterly bewildered by the atmosphere of the group (as I did, when I first accidentally walked into Chamber some years ago). Personally, I believe that our lexis revolves firmly around our director, Mr. Halop. This is because Halop exerts himself beyond the normal expectations of a choral director; he is equal parts intimidating teacher, passionate director, and surrogate father to some. When asked what role he plays

in the eyes of the students of Northwood, Halops grey eyes unfocused; he scratched his bald spot for just a few seconds, brow furrowed, and then quickly locked his eyes back on me. I believe Im simply a proxy for life. All Id like to do, all Id like to be to you all, is whatever you need me to be; Id just like to introduce you to your own infinite potential. He then added, with a wink, But you know all about that kind of thing, dont you, Shounak? Swales sixth and final criteria states that a community must have a threshold level of members with a suitable degree of relevant content and discoursal expertise (Swales 471). This is completely true for the Chamber community; the Chamber community is the most exclusive level of Choral music in the state, requiring a multi-stage audition and personality evaluation before acceptance. As a result, its members are highly qualified and either very skilled, very talented, or very determined; often, the members exhibit all the aforementioned qualities equally. This level of skill also implies a high standard of professionalism; often, when we rehearse a piece of music, we also analyze and research the material both individually and as a group in order to thoroughly understand the nuances and emotional weight of the music we are interpreting; according to Dalton Tran, in my experience, the line between a good performance and an amazing performance is how emotionally connected we are to the music (Tran, interview). Therefore, our communitys high level of expertise enables us to look past simple mechanical problems such as reading the music or singing the correct notes, and discuss the meaning of the piece. As a result, this enables us to reinforce our groups unity and strive towards achieving the common goal of making good music. After applying Swales six criterion to the Chamber community of Northwood High School, I have come to the conclusion that Chamber is indeed a discourse community, as it has met the requirements to be recognized as such.

You might also like

- Final Reflection and Welcome v2Document3 pagesFinal Reflection and Welcome v2api-251527289No ratings yet

- Swales MuraDocument3 pagesSwales Muraapi-251527289No ratings yet

- Audio Narrative Draft 1 ScriptDocument1 pageAudio Narrative Draft 1 Scriptapi-251527289No ratings yet

- Unit 4 FinalDocument8 pagesUnit 4 Finalapi-251527289No ratings yet

- Unit 4 First DraftDocument3 pagesUnit 4 First Draftapi-251527289No ratings yet

- Dear ReaderDocument2 pagesDear Readerapi-251527289No ratings yet

- Literacy Essay Second DraftDocument5 pagesLiteracy Essay Second Draftapi-251527289No ratings yet

- Owl InterviewDocument1 pageOwl Interviewapi-251527289No ratings yet

- Literacy Essay Final DraftDocument6 pagesLiteracy Essay Final Draftapi-251527289No ratings yet

- Ethnography Research LogDocument2 pagesEthnography Research Logapi-251527289No ratings yet

- Literacy Essay Draft 1Document1 pageLiteracy Essay Draft 1api-251527289No ratings yet

- Ethnography ReflectionDocument2 pagesEthnography Reflectionapi-251527289No ratings yet

- Ethnography CitationsDocument1 pageEthnography Citationsapi-251527289No ratings yet

- Ethnography Draft 2Document5 pagesEthnography Draft 2api-251527289No ratings yet

- Ethnography Draft 1Document5 pagesEthnography Draft 1api-251527289No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Meridian Passage 08jDocument12 pagesMeridian Passage 08jiZhionNo ratings yet

- Gujarat Technological University Subject: VLSI Technology & Design Code:2161101 Topic - 3 - MOS TransistorDocument122 pagesGujarat Technological University Subject: VLSI Technology & Design Code:2161101 Topic - 3 - MOS Transistorbakoliy218No ratings yet

- Jurnal-Ayu Santika NovinDocument10 pagesJurnal-Ayu Santika NovinSitti Hajar ONo ratings yet

- Neelam Shahzadi CVDocument3 pagesNeelam Shahzadi CVAnonymous Jx7Q4sNmtNo ratings yet

- History PPT 1Document24 pagesHistory PPT 1Akash SharmaNo ratings yet

- Karmila Kristina Paladang, Siane Indriani, Kurnia P. S DirgantoroDocument11 pagesKarmila Kristina Paladang, Siane Indriani, Kurnia P. S DirgantoroDaniel DikmanNo ratings yet

- Restorative Justice and The Prison MinistryDocument15 pagesRestorative Justice and The Prison MinistrypfipilipinasNo ratings yet

- 3ABN World 2016 11LDocument27 pages3ABN World 2016 11LjavierNo ratings yet

- Guide 2017Document48 pagesGuide 2017Kleberson MeirelesNo ratings yet

- Document 2Document7 pagesDocument 2rNo ratings yet

- On The Metres of Poetry and Related Matters According To AristotleDocument61 pagesOn The Metres of Poetry and Related Matters According To AristotleBart MazzettiNo ratings yet

- 05 AHP and Scoring ModelsDocument32 pages05 AHP and Scoring ModelsIhjaz VarikkodanNo ratings yet

- Assignment Article 2Document14 pagesAssignment Article 2Trend on Time0% (1)

- Roulette WarfareDocument2 pagesRoulette WarfareAsteboNo ratings yet

- Paschal CHAPTER TWODocument20 pagesPaschal CHAPTER TWOIdoko VincentNo ratings yet

- Moles and Equations - Worksheets 2.1-2.11 1 AnsDocument19 pagesMoles and Equations - Worksheets 2.1-2.11 1 Ansash2568% (24)

- SIOP Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesSIOP Lesson PlanSmithRichardL1988100% (3)

- Problems of Education in The 21st Century, Vol. 76, No. 3, 2018Document137 pagesProblems of Education in The 21st Century, Vol. 76, No. 3, 2018Scientia Socialis, Ltd.No ratings yet

- BSBMGT608C Manage Innovation Case Study AC GilbertDocument13 pagesBSBMGT608C Manage Innovation Case Study AC Gilbertbacharnaja9% (11)

- Rational Numbers Notes2Document5 pagesRational Numbers Notes2Midhun Bhuvanesh.B 7ANo ratings yet

- Ulep vs. Legal Clinic, Inc., 223 SCRA 378, Bar Matter No. 553 June 17, 1993Document19 pagesUlep vs. Legal Clinic, Inc., 223 SCRA 378, Bar Matter No. 553 June 17, 1993CherNo ratings yet

- Advocate - Conflict of InterestDocument7 pagesAdvocate - Conflict of InterestZaminNo ratings yet

- PI2016 - Geotechnical Characterization of Clearwater Shales For DesignDocument8 pagesPI2016 - Geotechnical Characterization of Clearwater Shales For DesignmauricioNo ratings yet

- Snelgrove Language and Language Development Fianl ProjectDocument4 pagesSnelgrove Language and Language Development Fianl Projectapi-341640365No ratings yet

- 2017 Wassce Gka - Paper 2 SolutionDocument5 pages2017 Wassce Gka - Paper 2 SolutionKwabena AgyepongNo ratings yet

- Netflix PPT by OopsieanieeDocument12 pagesNetflix PPT by OopsieanieeAdhimurizkyrNo ratings yet

- Samsung Mobile: Market Share & Profitability in SmartphonesDocument15 pagesSamsung Mobile: Market Share & Profitability in SmartphonesTanmay WadhwaNo ratings yet

- Brooklyn College - Syllabus 3250 - Revised 2Document8 pagesBrooklyn College - Syllabus 3250 - Revised 2api-535264953No ratings yet

- Đề Thi và Đáp ÁnDocument19 pagesĐề Thi và Đáp ÁnTruong Quoc TaiNo ratings yet

- Ms. Irish Lyn T. Alolod Vi-AdviserDocument17 pagesMs. Irish Lyn T. Alolod Vi-AdviserIrish Lyn Alolod Cabilogan100% (1)