Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Masscommresearch Concept Explication

Uploaded by

Huzaifah Bin SaeedCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Masscommresearch Concept Explication

Uploaded by

Huzaifah Bin SaeedCopyright:

Available Formats

Theoretical Definitions Self-esteem gives rise to many problems in research due to its subjective nature.

These inconsistencies are mainly due to the difficulty of conceptualizing or defining the term. Self-esteem is continually revealing itself under different definitions and implications. Gail McEachron (1993) defines self-esteem as the judgment one makes about their self-concept. Self-concept refers to the attributes one has. McEachron (1993, p. 67) supports this definition with the work of Dr. Morris Rosenberg whom defines self-esteem as the attitude one holds toward themselves as an object (McEachron, 1993, pg. 8-9). In short, Dr. Morris believed that self-esteem was measurable via assessing a subjects attitude about themselves as a thing. On the other hand, a second definition of self-esteem is the ratio of ones successes over their pretensions or failures. McEachron (1993) references James Williams work to explain. This definition of self-esteem requires the researcher to define success. For the purpose of this paper we will stick to Will iams definition of success used in the development of this definition of self-esteem: an achievement one makes in an area considered to be of importance to the person whose self-esteem is being measured. The failures must also be in an area of equal importance to the subject. Therefore, this definition can be understood as the ratio of successes of importance to failures of equal importance. Additional definitions of self-esteem include the theory of libidthal cathexis and the theory of self-dynamism. Libidthal cathexis refers to the successful fulfillment of desires held by the super ego (Jackson, 1984). The ability or inability to fulfill these desires determines ones self-esteem. The idea is that individuals whom are able to satisfy their

super ego will possess a higher self-esteem than those whom cannot. Secondly, selfdynamism is a relatively enduring configuration of energy which manifests itself in characterizable processes in interpersonal relations (Sullivan & Mullahy, YR, p. 128). This definition emphasizes the importance of interpersonal relationships regarding the development of self-esteem. Operational Definitions Despite the numerous theoretical definitions of self-esteem, there are only a minute number of operational definitions used today. The most common is the Rosenberg SelfEsteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965). This scale measures self-esteem via a survey. Every answer on the survey is assigned a point value with more points being rewarded for answers demonstrating high self-esteem and vice versa. The subjects survey is scored and the subject is placed into a category. For example, some categories might be high self-esteem, average self-esteem, below average, or critical. The other operational definition used today is less sophisticated. It employs the use of an interview that asks similar questions that would be used on a self-esteem survey. While conducting the interview, the researcher is observing nonverbal cues such as eyecontact, smiling, fidgeting, and hand-wringing. The researcher counts the number of times they observe these and other behaviors to determine self-esteem (Jackson, 1984). A related operational definition is The Body-Esteem Scale (Franzoi &Shields, 1984). This scale does not directly measure self-esteem but rather uses a point scale like the one used with the Rosenberg scale to determine the esteem one has towards their bodily appearance by assigning questions a category such as sexual attractiveness to survey questions.

Comparison and Recommendations The theoretical definitions discussed prior can be classified into two camps. The first of which is a general, broad definition open to interpretation. These definitions have a wide range of applications and can be used relatively easily. The biggest drawback of these definitions is that they tell us little about the meaning of the phenomena. Rather, these definitions seek to merely define. The second camp consists of more specified definitions. These definitions allow for an easily defined operational definition and a very clear way of indicating self-esteem or the lack thereof. However, these definitions tend to be complicated and results are less reliable due to the subjective nature of success and failure. Researchers should use the definition that most completely defines self-esteem in a way that all test subjects can understand. For this reason, self-esteem as defined by McEachron (1993) is recommended as the most comprehensive and understood definition and also as the most applicable. The operational definitions of self-esteem tend to fall into the same to camps. The behaviors observed during an interview fall into the first camp while the Rosenberg SelfEsteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965) and the Body-Esteem Scale (Franzoi & Shields, 1984) fall into the second. The negatives regarding the interview approach is record-ability. It is difficult to record observed behaviors as a numeric measurement. Also, extraneous variables are more likely to interfere than in other operational definitions. For example, the subject may have looked down because a question evoked a strong emotion or memory rather than due to

lack of self-esteem. On the other hand, the interview allows for a more in-depth understanding of the test subject. Both the Rosenberg scale and the body-esteem scale provide a way to concretely measure and record self-esteem or body-esteem, respectively. There is only one way to understand and read both scales, thus allowing for more reliable results. The Rosenberg scale also measures self-esteem more completely than the body-esteem scale. The bodyesteem scale is only obliquely related to the self-esteem because in reality it measures the esteem one has for their own body. Operational definitions should be concrete and easily recordable. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg 1965) is the most concrete way of measuring self-esteem because it is not open for interpretationthere is only one way to use the Rosenberg scale. In conclusion, theoretical and operational definitions need to be chosen based on their completeness, understandability, and record-ability.

References Franzoi, S.L. (1994). Further evidence of the reliability and validity of the body esteem scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 50, 237-239. Fanzoi, S.L. & Shields, S.A. (1984). The body-esteem scale: Multidimensional structure and sex differences in a college population. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48, 173-178. Jackson, M.R. (1984). Self-esteem and meaning: A life-historical investigation. Albany: State University of New York Press. McEachron, G.A. (1993). Student self-esteem: Integrating the self. Lancaster, PA: Technomic Pub. Sullivan, H.S. & Mullahy, P. (1953). Conceptions of Modern Psychiatry. New York: Norton.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Women's GarmentsDocument50 pagesWomen's GarmentsHuzaifah Bin SaeedNo ratings yet

- Psychosocial Development in Middle AdulthoodDocument4 pagesPsychosocial Development in Middle AdulthoodHuzaifah Bin Saeed100% (1)

- Safety Leadership NewDocument35 pagesSafety Leadership NewdhabriNo ratings yet

- Chiron in The Houses of The Natal ChartDocument3 pagesChiron in The Houses of The Natal ChartRamram07No ratings yet

- Relationship Between Body Image and Self EsteemDocument36 pagesRelationship Between Body Image and Self EsteemHuzaifah Bin Saeed85% (20)

- Infants Social and Emotional Developmental Stages PDFDocument12 pagesInfants Social and Emotional Developmental Stages PDFHuzaifah Bin SaeedNo ratings yet

- The Methodology of Teaching Home EconomicsDocument12 pagesThe Methodology of Teaching Home EconomicsHuzaifah Bin Saeed100% (6)

- Speech On FriendshipDocument4 pagesSpeech On Friendshipkishi8mempin75% (4)

- Maria Khalid BS (Hons) 3 Semester Section B Economics Assignment: Demand Dated: 23 October 2013Document4 pagesMaria Khalid BS (Hons) 3 Semester Section B Economics Assignment: Demand Dated: 23 October 2013Huzaifah Bin SaeedNo ratings yet

- Students - Perception of Home Economics UndergraduateDocument2 pagesStudents - Perception of Home Economics UndergraduateHuzaifah Bin Saeed100% (2)

- Reasearch PaperDocument25 pagesReasearch PaperHuzaifah Bin SaeedNo ratings yet

- Process Analysis EssayDocument4 pagesProcess Analysis EssayHuzaifah Bin SaeedNo ratings yet

- Report WritingDocument1 pageReport WritingHuzaifah Bin SaeedNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument101 pagesThesisHuzaifah Bin SaeedNo ratings yet

- Types of ComputerDocument9 pagesTypes of ComputerHuzaifah Bin SaeedNo ratings yet

- Physical Development in Middle ChildhoodDocument26 pagesPhysical Development in Middle ChildhoodHuzaifah Bin SaeedNo ratings yet

- Types of ComputerDocument9 pagesTypes of ComputerHuzaifah Bin SaeedNo ratings yet

- Physical DevelopmentDocument3 pagesPhysical DevelopmentHuzaifah Bin SaeedNo ratings yet

- Developmental Stages PDFDocument19 pagesDevelopmental Stages PDFHuzaifah Bin SaeedNo ratings yet

- I. Design:: Types of Design: Structural Design Decorative DesignDocument10 pagesI. Design:: Types of Design: Structural Design Decorative DesignHuzaifah Bin SaeedNo ratings yet

- Group DiscussionDocument4 pagesGroup DiscussionHuzaifah Bin SaeedNo ratings yet

- Perdev - Explanation How You Developed Personal RelationshipsDocument2 pagesPerdev - Explanation How You Developed Personal RelationshipsRodz QuinesNo ratings yet

- How Your Child Might Feel If Cyberbullied: OverwhelmedDocument4 pagesHow Your Child Might Feel If Cyberbullied: OverwhelmedFlorina Secuya100% (1)

- Lived Experiences of Children of Male Police OfficerDocument34 pagesLived Experiences of Children of Male Police OfficerLenard LagasiNo ratings yet

- Adventure To Greatness - AdmainDocument2 pagesAdventure To Greatness - AdmainHeba ADMAINNo ratings yet

- Ar2006-0915-0923 Gorse Et Al PDFDocument9 pagesAr2006-0915-0923 Gorse Et Al PDFMosisa GeremuNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0190740923004619 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0190740923004619 Maintatiana martinezNo ratings yet

- Ten Elements of Best Practice in Bullying Prevention & InterventionDocument2 pagesTen Elements of Best Practice in Bullying Prevention & InterventionLaura BeatrizNo ratings yet

- Sheinov (2018)Document6 pagesSheinov (2018)arifbijakz20No ratings yet

- Ideas and Issues in Public AdministrationDocument10 pagesIdeas and Issues in Public AdministrationnikhilNo ratings yet

- Chap 7: Foundations of Group Behavior & Understanding Work Teams Book Chap: 9 & 10Document34 pagesChap 7: Foundations of Group Behavior & Understanding Work Teams Book Chap: 9 & 10Borhan UddinNo ratings yet

- Midterm Reviewer Counseling PsychologyDocument5 pagesMidterm Reviewer Counseling PsychologyRivera EmieNo ratings yet

- Sensing Ethical ExtratimDocument3 pagesSensing Ethical ExtratimcringeNo ratings yet

- The Moral AgentDocument4 pagesThe Moral AgentMaria victoria SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Activity 2: Types of Communication in The WorkplaceDocument1 pageActivity 2: Types of Communication in The WorkplaceJers Gaming YTNo ratings yet

- Bullies 3Document5 pagesBullies 3api-291823000No ratings yet

- Building Interview SkillsDocument3 pagesBuilding Interview Skillscomedesroseann108No ratings yet

- Collective Behavior, Social Movements, and Social ChangeDocument19 pagesCollective Behavior, Social Movements, and Social ChangeLexuz GatonNo ratings yet

- Form MCQ (v1)Document3 pagesForm MCQ (v1)Jo'anne SpouseNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6.emotionalDocument20 pagesChapter 6.emotionalMurni AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Relapse Autopsy AbbreviatedDocument4 pagesRelapse Autopsy AbbreviatedAhmed HassanNo ratings yet

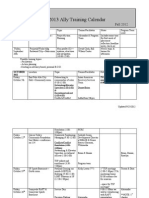

- Fall 2012 Ally Training Calendar 1Document5 pagesFall 2012 Ally Training Calendar 1api-229505730No ratings yet

- Questions For Young PeopleDocument1 pageQuestions For Young PeopleKJNo ratings yet

- Module 6 Paper Ogl 350Document5 pagesModule 6 Paper Ogl 350api-660756256No ratings yet

- Valencia Reginald G, Performance Task 4 Social Agents and How They Impact UsDocument2 pagesValencia Reginald G, Performance Task 4 Social Agents and How They Impact UsReginald ValenciaNo ratings yet

- The Last Leaf (Notebook Work)Document6 pagesThe Last Leaf (Notebook Work)Yashvi PatelNo ratings yet

- Miri Malo Dis EmoDocument3 pagesMiri Malo Dis EmoGergely IllésNo ratings yet

- Group DynamicsDocument30 pagesGroup DynamicsNusrat jahanNo ratings yet