Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jurnal Striktur Ncbi

Jurnal Striktur Ncbi

Uploaded by

Rangga Ro'ufa Amri0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views5 pagesjurnal

Original Title

jurnal striktur ncbi

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentjurnal

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views5 pagesJurnal Striktur Ncbi

Jurnal Striktur Ncbi

Uploaded by

Rangga Ro'ufa Amrijurnal

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

REVIEW

Management of urethral strictures

A R Mundy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Postgrad Med J 2006;82:489493. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2005.042945

Controlled clinical trials are unusual in surgery, rare in

urology, and almost non-existent as far as the management

of urethral stricture is concerned. What data there are

come largely from so called expert opinion and the

quality of this is variable. None the less, the number of so

called experts, past and present, is comparatively small

and in broad principle their views more or less coincide.

Although this review is therefore inevitably biased, it is

unlikely that expert opinion will take issue with most of the

general points raised here.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Correspondence to:

Professor A R Mundy, The

Institute of Urology,

London, 2A Maple House,

Ground Floor, Rosenheim

Wing, 25 Grafton Way,

London WC1E 6AU, UK;

kelly.higgs@uclh.nhs.uk

Submitted

1 November 2005

Accepted 9 February 2006

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

U

rethral strictures have always been com-

mon. We know something about how the

ancient Egyptians treated stricture disease

4000 years ago and other civilisations since and

indeed not much has changed until about 50

years ago.

Urethral strictures are still common now.

Hospital Episode Statistics in the UK and similar

data from the USA suggest that men are affected

with an increasing incidence from about 1 in

every 10 000 men aged 25 to about 1 in every

1000 men ages 65 or more. Traditionally,

strictures in the past were caused by gonococcal

urethritis. These days this is rare in the developed

world although still common in some societies.

In the UK, aetiology is almost equally divided

between inflammation, trauma, and idio-

pathic. The inflammation category includes

non-specific urethritis and, increasingly com-

monly, lichen sclerosus, formerly known as

balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO). Trauma is

more usually iatrogenic and attributable to

instrumentation these days but also includes

the more dramatic fall astride injuries to the

bulbar urethra and pelvic fracture related injuries

to the membranous urethra and bulbo-membra-

nous junction. Many idiopathic strictures are

idiopathic because their cause is lost in the

mists of time but many of these occur at the

junction of the proximal and middle sections of

the bulbar urethra in adolescents and young

adults with no previous history and many believe

this represents a congenital anomaly. Among the

established congenital anomalies of the lower

urogenital tract, hypospadias is one of the more

common and although this is not itself asso-

ciated with stricture, a stricture is an occasional

consequence of hypospadias surgery in early

childhood and an increasingly common cause

of strictures in the trauma category.

The pathology of urethral stricture disease is

poorly understood. External trauma generally

causes partial or complete disruption of an

otherwise normal urethrathat is clear. How a

stricture develops in other circumstances

remains unclear but it would seem that for

whatever reason a scar develops as a conse-

quence of changes in the structure and function

of the urethral epithelium and the sub-epithelial

spongy tissue causing a fibrotic narrowing of the

urethra.

1

Secondary changes in the epithelium

more proximally develop there afterwards caus-

ing a progressive stricturing of an increasing

length of the urethra from before backwards.

Longstanding urethral obstruction may cause

secondary complications in the rest of the

urinary tract.

2

CLI NI CAL ASSESSMENT AND

I NVESTI GATI ON

Trauma aside, most patients present with slow

and progressive deterioration of the urinary

stream leading to a feeling of incomplete empty-

ing as obstruction progressively develops. More

severe cases may be complicated by haematuria

or recurrent urinary infection and its sequalae.

It is usual practice for patients with lower

urinary tract symptoms to have their urinary

flow rate measured as part of initial investiga-

tion. In those who have a urethral stricture the

peak flow rate is typically low but the flow

pattern is characteristically flat (fig 1). This flow

pattern is almost pathognomonic of a urethral

stricture; certainly it should lead to a urethro-

gram as the next step in investigation. If properly

performed, this will show the exact site and

length of the stricture and most of its potential

complications (fig 2). Ultrasound evaluation may

show a thickening of the bladder wall associated

with longstanding outflow obstruction, and a

presence of residual urine. If these two signs are

present, an ultrasound scan of the kidneys

should be the next step to look for signs of

obstructive uropathy and in the presence of

hydroureteronephrosis, there should be an esti-

mate of renal function.

TREATMENT

The normal urinary flow rate in young and

middle aged men is generally greater than 15 ml/

second and the flow pattern a bell shaped curve.

Patients with an established diagnosis of ure-

thral stricture but who have a flow rate greater

than 10 ml/second and normal bladder thick-

ness, complete bladder emptying and who are

untroubled by recurrent urinary infection do not

necessarily require any treatment but they

should be kept under review. A flow rate less

than 10 ml/second is more commonly associated

with symptoms and with the secondary effects

such as recurrent haematuria or recurrent

urinary tract infection and with features of overt

489

www.postgradmedj.com

bladder obstruction on ultrasonography, but this is not

necessarily so. If the stricture is troublesome it should be

treated; if not the patient should be kept under review. With

a flow rate of less than 5 ml/second, abnormalities such as

those listed above are much more likely and the patient is

potentially at risk of acute retention, although this is a lot less

common than one would expect from the severity of the

narrowing of the urethra that is seen in such a situation. In

these patients treatment is advisable even if symptoms of

voiding difficulty are not troublesome.

The time honoured method of treatment is urethral

dilatationthe passage of calibrated instrumentsusually

made of metal and called sounds, Bougies or, more simply,

urethral dilators. They are generally straight through most of

their length with a hockey stick curve at the end and are

calibrated according to the French system, which relates the

size of the urethral dilator to the urethral circumference in

millimetres. The normal urethral calibre is 2426F (French)

at the external urinary meatus, a little wider in the penile

urethra, wider still in the bulbar urethra (about 36F), and

then narrower again in the posterior urethra, above the level

of the perineal membrane.

Some patients with urethral stricture have the diagnosis

made on endoscopic evaluation of the lower urinary tract.

The principle of urethral dilatation is to stretch the urethral

stricture up or otherwise, and more commonly, to disrupt it.

A graduated series of dilators from smaller to larger size is

passed to restore the urethral calibre to normal, or there-

abouts. The alternative form of instrumentation, also with a

history measured in thousands of years, is urethrotomy.

Initially, this was performed blindly by increasingly sophis-

ticated means until visual internal urethrotomy was devel-

oped about 35 years ago. Visual control of the process might

be expected to give better results but in fact, there is no

evidence that this is so. As a general rule however urethral

dilatation might best be reserved for more straightforward

strictures that can be dilated in an office setting using topical

anaesthesia whereas visual internal urethrotomy is probably

better for more complicated strictures, performed in a day

case operating theatre under regional or general anaesthesia.

Both procedures are generally regarded as simple and

straightforward but in fact carry a significant risk of

complications.

3

It is now generally accepted that urethrotomy and

dilatation are equally effective and can be expected to cure

about 50% of short bulbar urethral strictures when first used.

If the procedure has to be repeated, it is rarely curative and it

is rarely curative even the first time in strictures other than in

the bulbar urethra.

46

When the stricture recurs, it usually does so within weeks

or months and almost always within two years. Those that

recur comparatively infrequently might be palliated (rather

than cured) by repeat instrumentation and, as long as this is

agreeable to the patient and is uncomplicated by bleeding or

sepsis,

3

such palliation might be perfectly acceptable. If

instrumentation is required more frequently or is complicated

or unacceptable to the patient in the long term, then

urethroplasty is the only curative option.

Alternatives have been recommended, such as the use of a

laser rather than a cold knife for internal urethrotomy; an

indwelling urethral stent to hold the urethra open; or much

more commonly, the use of clean intermittent self catheter-

isation.

7

None of these, however, are curative; the laser is

expensive as well as ineffective; stents, although popular a

decade ago, commonly do more harm than good

810

; and only

self catheterisation is occasionally helpful: for the patient

who is not fit for, or is otherwise unwilling to undergo, a

urethroplasty.

GENERAL PRI NCI PLES OF URETHROPLASTY

1113

Ideally, one would like to excise a urethral stricture and join

the two healthy ends of urethra on either side together again

to restore continuity and calibre. Unfortunately, this can only

be done with short urethral strictures because of limitations

of elasticity and length before erectile function is compro-

mised. Excision and end to end anastomosis, or an

anastomotic urethroplasty as it is more commonly called, is

however best, even if it can only be used for short strictures of

the bulbar urethra and more proximally, in the membranous

urethra, because it gives the best and most sustained results

in terms of both a low re-stricture rate and a low

complication rate. Whether this high success rate is

50

40

30

20

10

0

0 05 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55

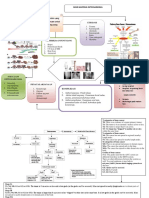

Figure 1 Flow pattern of a patient with

a urethral stricture.

A B

Figure 2 An uncomplicated (A) and a

somewhat more complicated stricture

(B).

490 Mundy

www.postgradmedj.com

attributable to the technique itself or because those strictures

that are amenable to an anastomotic urethroplasty generally

occur in younger patients with a more localised urethral

problem (such as trauma) is not clear.

When a stricture is too long for anastomotic urethroplasty

the alternative is some form of substitution urethroplasty.

Here, there are two alternative approaches. The first is to

excise the urethral stricture and perform a circumferential

repair of the urethra. Intuitively, this would seem to be a

sensible approach but in practice, a circumferential repair

needs to be staged to give satisfactory results or, if performed

in one stage, tends to give less satisfactory results than the

alternative approach of incising the stricture and then putting

on a patch to restore urethral calibre at that point

(stricturotomy and patch).

ANASTOMOTI C URETHROPLASTY

Anastomotic urethroplasty is generally only applicable in two

situations. Firstly, for short strictures of the bulbar urethra,

no more than 12 cm long, which are generally attributable

to external trauma or are otherwise idiopathic in origin

(possibly congenital). The external trauma is usually a fall

astride injury. The second situation is a pelvic fracture related

injury of the membranous urethra or bulbo-membranous

junction.

The general principles here are to mobilise the bulbar

urethra fully, capitalising on its elasticity to overcome any

defect in length as a result of excision of a short stricture or to

bridge a gap caused by complete disruption because of

external trauma. Should the elasticity of the urethra and

mobilisation alone be insufficient to bridge any defect then

the second general principle is to straighten out the natural

curve of the bulbar urethra by a sequential series of

manoeuvres including separation of the crura at the base of

the penis, wedge pubectomy of the inferior pubic arch, and, if

necessary, re-routing of the urethra around the shaft of the

shaft of the penis until the course of the bulbar urethra from

the penoscrotal junction to the apex of the prostate is a

straight line rather than the semi-circle that it normally is

(fig 3).

1416

SUBSTI TUTI ON URETHROPLASTY

Unlike anastomotic urethroplasty this can be used anywhere

in the urethra. When an anastomotic repair is possible and

appropriate this should be used in preference because it gives

better and more durable results. Substitution urethroplasty

should not therefore be used universally; it should be used

selectively for those strictures of the bulbar urethra that are

too long for an anastomnotic repair and all strictures of the

penile urethra in which an anastomotic repair would cause

unacceptable penile deformity on erection.

As a stricturotomy and patch is generally more successful

than an excision and circumferential repair then this is the

procedure of choice unless a urethral segment positively

needs to be excised as after previous surgery for hypospadias

when the urethra is irretrievably scarred, in lichen sclerosus

when it is irretrievably fibrotic, or in rare situations such as

with urethral arteriovenous malformations or tumours.

17

WHAT SORT OF A PATCH SHOULD BE USED?

It might seem intuitive that a skin flap, which brings with it

its own blood supply, would give better results than a free

graft, which has to develop its own blood supply having been

raised from a remote site. This is not however the case in

most circumstances.

18 19

Indeed, for most strictures the

results are just as good with a graft as with a flap as long

as the graft is a thin, full thickness graft with a dense sub-

dermal plexus such as full thickness graft of penile shaft skin

or foreskin, a post-auricular (from behind the ear) full

thickness graft, or a buccal mucosal graft (from inside of the

cheek). Buccal mucosa is currently the preferred graft

material, if only because it has the least donor site

morbidity.

2022

Occasionally a flap must be used when the local conditions

are not favourable for a graft as when there is extensive

scarring from previous surgery or active infection or previous

radiotherapy or when the stricture is unusually long or trans-

sphincteric. In such cases a flap of local genital skin pedicled

on the dartos layer of the penis (which is highly vascular) is

preferred.

23 24

When a segment of urethra has to be excised, usually

because of dense scarring in the penile urethra for whatever

reason, then a circumferential repair must be performed. It is

possible to do this in one stage, particularly for short

strictures in the most distal part of the penile urethra, but

in other circumstances a two stage repair is safer and gives

the best long term results.

7

In such circumstances a graft is

interposed as a flat plate between the two ends of the urethra

where a segment has been excised (or between the end of the

urethra and the external meatus if it is the most distal

A B

3

1

2

3

4

5

Figure 3 Illustrates how straightening

out the natural curve of the bulbar

urethra allows the surgeon to bridge a

considerable defect in urethral length.

The numbers are distances in

centimetres from the penobulbar

junction to the apex of the prostate at

usual radiographic magnifications.

Urethral strictures 491

www.postgradmedj.com

segment of the urethra that is involved). The flat plate is then

rolled in to form a tube and closed in layers at a second stage

three to six months later.

STRI CTURES BY SI TE AND TYPE

The urethra is typically described as having an anterior and

posterior segment. The anterior segment is surrounded by

corpus spongiosum and is divided into the penile (or

pendulous in American terminology) and bulbar segments.

The bulbar segment is the part enclosed by the bulbo-

spongiosus muscle. The posterior urethra is surrounded by

the prostate and the urethral sphincter and is divided into the

prostatic and membranous parts respectively. There is

insufficient space here to discuss any more sophisticated

anatomical sub-division of the posterior urethra; likewise,

strictures of the bladder neck and of the prostatic urethra,

usually the result of surgical treatment, particularly new

technology such as cryotherapy and laser therapy, which are

not generally considered as urethral strictures, will not be

considered here.

Posterior urethral strictures of the membranous urethra or

bulbo-membranous junction are usually the result of pelvic

fracture related urethral injury and are treated by anastomo-

tic urethroplasty in which the full range of manoeuvres

referred to above may be used and that may be an extremely

difficult surgical undertaking.

1416

Membranous urethral

strictures are sometimes the result of instrumentation as in

transurethral resection of the prostate in which case they are

known as sphincter strictures because it is fibrosis within

the urethral sphincter mechanism that is the primary

problem. To reserve sphincter function and therefore avoid

incontinence such strictures are best treated by urethral

dilatation where possible.

In the anterior urethra, bulbar urethral strictures are more

common than penile urethral strictures except in specialist

units where penile urethral strictures, because of previous

hypospadias surgery or lichen sclerosis,

25

are becoming

increasingly common. Short bulbar strictures as a result of

trauma or otherwise congenital are best treated by anasto-

motic urethroplasty. If a bulbar stricture is too long for

anastomotic urethroplasty, as is commonly the case, then a

stricturotomy and patch procedure is performed. When

anastomotic urethroplasty is possible this is usually a simple

and straightforward procedure when compared with anasto-

motic urethroplasty of the posterior urethra. A stricturotomy

and patch will usually use a buccal mucosal graft as a

patch.

2022

In the penile urethroplasty a stricturotomy and patch is

possible for simple strictures

26

but in more complicated

circumstances an excision and circumferential repair will be

necessary in which buccal mucosa may be used unless

preputial or penile shaft skin would be more appropriate. For

more complication situations, a staged reconstruction will be

used.

17

THE FUTURE OF URETHRAL STRI CTURE SURGERY

The results of anastomotic repair are so good and so well

sustained that it seems unlikely that this will be superseded

at any stage in the foreseeable future by any new develop-

ment.

Most strictures requiring substitution urethroplasty also do

well with modern surgical technique but if the procedure

could be performed endoscopically rather than by open

surgery then this would clearly be an advantage to the

patient. The real problems are the more complicated

strictures, which are generally longer and have already

undergone previous surgery and have recurred. They are also

typically in the penile urethra and associated with lichen

sclerosis. Many urologists hopes have been raised by

developments in tissue engineering to provide an alternative

source of material for repair of these difficult strictures. I am

somewhat sceptical about these developments because I do

not think it is the lack of the material that is the problemI

think it is the nature of the underlying disease. Future

surgical developments, in my opinion, will be the conse-

quence of a better understanding of the nature of the disease

in such patients and from a different approach to treating the

diseased but not actually strictured urethra rather than from

improvement in technique alone.

Funding: none.

Conflicts of interest: none.

REFERENCES

1 Chambers R, Baitera B. The anatomy of urethral stricture. BJU

1977;49:54551.

2 Romero Perez P, Mira Linares A. Complications of the lower urinary tract

secondary to urethral stenosis. Actas Urol Esp 1996;20:78693.

3 Devereux M, Burfield G. Prolonged follow-up of urethral strictures treated by

intermittent dilatation. BJU 1970;42:2319.

4 Pansadoro V, Emiliozzi P. Internal urethrotomy in the management of anterior

urethral strictures: long-term follow up. J Urol 1996;156:735.

5 Steenkamp J, Heyns C, De Kock M. Internal urethrotomy versus dilatation as

treatment for male urethral strictures: a prospective, randomised comparison.

J Urol 1997;157:98101.

6 Heyns C, Steenkamp JW, De Kock ML, et al. Treatment of male urethral

strictures: is repeated dilatation of internal urethrotomy useful? J Urol

1998;160:3568.

Summary of the general pri nci pl es of

urethropl asty

N

Urethral and visual internal urethrotomy are equally

effective

N

50% of short bulbar strictures are cured by the very first

dilatation or urethrotomy

N

Penile urethral strictures are rarely cured by dilatation

or urethrotomy

N

If a patient develops a recurrent stricture after a

previous urethrotomy or dilatation, however long the

interval, further instrumentation is never curative

N

The only curative alternative is urethroplasty

N

Whenever a urethroplasty is necessary an anastomotic

urethroplasty is preferable because it has a lower re-

stricture rate, success is maintained long term and the

complication rate is lower

N

Substitution urethroplasty is necessary for longer

bulbar strictures and all strictures of the penile urethra

N

For most urethral strictures requiring substitution

urethroplasty a stricturotomy and patch is preferable

to excision and a tube-graft flap

N

Grafts and flaps are equally good in most circum-

stances

N

In the bulbar urethra grafts are quicker and easier

N

A dorsal stricturotomy and patch has a higher success

rate and a lower complication rate than ventral

stricturotomy and patch

N

Buccal mucosal grafting has advantages for strictur-

otomy and patch in the bulbar urethra

N

In the penile urethra a flap is quicker and easier

N

When a circumferential repair is required a two stage

reconstruction is safer and more reliable than a one

stage technique

492 Mundy

www.postgradmedj.com

7 Harriss D, Beckingham IJ, Lemberger RJ, et al. Long-term results of intermittent

low-friction self-catheterisation in patients with recurrent urethral strictures.

BJU 1994;74:7902.

8 Milroy E, Chapple C, Wallsten H. A new stent for the treatment of urethral

strictures: preliminary report. BJU 1989;63:3926.

9 Badlani G, Press SM, Defaclo A, et al. Urolume endourethral prosthesis for the

treatment of urethral strictures disease: long-term results of the North

American multicenter urolume trial. Urology 1995;45:84656.

10 Milroy E, Allen A. Long-term results of urolume urethral stent for recurrent

urethral strictures. J Urol 1996;155:9048.

11 Mundy A. Results and complications of urethroplasty and its future. BJU

1993;71:3225.

12 Andrich DE, Mundy AR. Urethral strictures and their surgical treatment. BJU Int

2000;86:57180.

13 Turner-Warwick R. Urethral stricture surgery. In: Mundy A, ed.

Current operative surgeryurology. London: Bailliere Tindall,

1988:160218.

14 Webster G, Ramon J. Repair of pelvic fracture posterior urethral defects using

an elaborated perineal approach: experience with 74 cases. J Urol

1991;145:7448.

15 Koraitim M. The lessons of 145 post traumatic posterior urethral strictures

treated in 17 years. J Urol 1995;153:636.

16 Mundy A. Reconstruction of posterior urethral distraction defects. Atlas Urol

Clin North Am 1997;165:14925.

17 Greenwell T, Venn S, Mundy A. Changing practice in anterior urethroplasty.

BJU Int 1998;83:6315.

18 Jordan G, Devine P. Application of tissue transfer techniques to the

management of urethral strictures. Semin Urol 1987;5:21935.

19 Wessels H, McAninch J. Current controversies in anterior urethral stricture

repair: free-graft versus pedicled skin-flap reconstruction. World J Urol

1998;16:17580.

20 Barbagli G, Selli C, di Cello V, et al. A one-stage dorsal free-graft

urethroplasty for bulbar urethral strictures. BJU 1996;78:92932.

21 Iselin C, Webster G. Dorsal onlay urethroplasty for urethral stricture repair.

World J Urol 1998;16:1815.

22 Andrich D, Mundy A. The Barbagli procedure gives the best results for patch

urethroplasty of the bulbar urethra. BJU Int 2001;88:3859.

23 Mundy A. The long-term results of skin inlay urethroplasty. J Urol

1972;107:97780.

24 Quartey J. One-stage penile/preputial island flap urethroplasty for urethral

stricture. J Urol 1985;134:47487.

25 Venn S, Mundy A. Urethroplasty for balanitis xerotica obliterans. BJU

1998;81:7357.

26 Orandi A. One-stage urethroplasty. BJU 1968;40:71719.

Clinical EvidenceCall for contributors

Clinical Evidence is a regularly updated evidence-based journal available worldwide both as

a paper version and on the internet. Clinical Evidence needs to recruit a number of new

contributors. Contributors are healthcare professionals or epidemiologists with experience in

evidence-based medicine and the ability to write in a concise and structured way.

Areas for which we are currently seeking contributors:

N

Pregnancy and childbirth

N

Endocrine disorders

N

Palliative care

N

Tropical diseases

We are also looking for contributors for existing topics. For full details on what these topics

are please visit www.clinicalevidence.com/ceweb/contribute/index.jsp

However, we are always looking for others, so do not let this list discourage you.

Being a contributor involves:

N

Selecting from a validated, screened search (performed by in-house Information

Specialists) epidemiologically sound studies for inclusion.

N

Documenting your decisions about which studies to include on an inclusion and exclusion

form, which we keep on file.

N

Writing the text to a highly structured template (about 1500-3000 words), using evidence

from the final studies chosen, within 8-10 weeks of receiving the literature search.

N

Working with Clinical Evidence editors to ensure that the final text meets epidemiological

and style standards.

N

Updating the text every 12 months using any new, sound evidence that becomes available.

The Clinical Evidence in-house team will conduct the searches for contributors; your task is

simply to filter out high quality studies and incorporate them in the existing text.

If you would like to become a contributor for Clinical Evidence or require more information

about what this involves please send your contact details and a copy of your CV, clearly

stating the clinical area you are interested in, to CECommissioning@bmjgroup.com.

Call for peer reviewers

Clinical Evidence also needs to recruit a number of new peer reviewers specifically with an

interest in the clinical areas stated above, and also others related to general practice. Peer

reviewers are healthcare professionals or epidemiologists with experience in evidence-based

medicine. As a peer reviewer you would be asked for your views on the clinical relevance,

validity, and accessibility of specific topics within the journal, and their usefulness to the

intended audience (international generalists and healthcare professionals, possibly with

limited statistical knowledge). Topics are usually 1500-3000 words in length and we would

ask you to review between 2-5 topics per year. The peer review process takes place

throughout the year, and out turnaround time for each review is ideally 10-14 days.

If you are interested in becoming a peer reviewer for Clinical Evidence, please complete the

peer review questionnaire at www.clinicalevidence.com/ceweb/contribute/peerreviewer.jsp

Urethral strictures 493

www.postgradmedj.com

You might also like

- ASPEN Enteral Nutrition Handbook, 2nd EditionDocument249 pagesASPEN Enteral Nutrition Handbook, 2nd EditionYohana Elisabeth Gultom100% (4)

- Teeth RestorabilityDocument6 pagesTeeth RestorabilityMuaiyed Buzayan AkremyNo ratings yet

- Teknik Operasi Splenektomi 2Document31 pagesTeknik Operasi Splenektomi 2sphericalfaNo ratings yet

- To Perforasi GasterDocument27 pagesTo Perforasi GasterPuthu BelegugNo ratings yet

- Pande Komang Gerry Paramesta: Decision Making in Bowel Obstruction: A Review byDocument32 pagesPande Komang Gerry Paramesta: Decision Making in Bowel Obstruction: A Review byanon_550250832100% (1)

- Striktur UrethraDocument7 pagesStriktur UrethraEl-yes Yonirazer El-BanjaryNo ratings yet

- BPHDocument10 pagesBPHMichelle SalimNo ratings yet

- Mediastinal Tumors: Kibrom Gebreselassie, MD, FCS-ECSA Cardiovascular and Thoracic SurgeonDocument52 pagesMediastinal Tumors: Kibrom Gebreselassie, MD, FCS-ECSA Cardiovascular and Thoracic SurgeonVincent SerNo ratings yet

- Diaphragma InjuryDocument18 pagesDiaphragma InjuryAhmedNo ratings yet

- Thyroid Cancer Diagnosis and ManagementDocument45 pagesThyroid Cancer Diagnosis and Managementapi-3704562100% (1)

- 2013 - Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple Procedure) TechniquesDocument11 pages2013 - Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple Procedure) TechniquesOlteanu IonutNo ratings yet

- Perforasi GasterDocument29 pagesPerforasi GasterrezaNo ratings yet

- Surgery of PancreasDocument30 pagesSurgery of PancreasmackieccNo ratings yet

- Jurnal CA TyroidDocument4 pagesJurnal CA TyroidErvina ZelfiNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Tyroid PDFDocument3 pagesJurnal Tyroid PDFVinnaNo ratings yet

- Trauma UrogenitalDocument17 pagesTrauma UrogenitalsultantraNo ratings yet

- Xanthogranulomatous PyelonephritisDocument14 pagesXanthogranulomatous PyelonephritisalaaNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Trauma - Dr. Febiansyah Ibrahim, SPB-KBDDocument32 pagesAbdominal Trauma - Dr. Febiansyah Ibrahim, SPB-KBDPrandyNo ratings yet

- Salter 15Document70 pagesSalter 15Kahfi Rakhmadian KiraNo ratings yet

- CCDuodenum Periampullary Neoplasms ChuDocument68 pagesCCDuodenum Periampullary Neoplasms ChuSahirNo ratings yet

- Metastasis Bone DiseaseDocument11 pagesMetastasis Bone DiseasedrkurniatiNo ratings yet

- Kompartemen SindromDocument9 pagesKompartemen SindromPutri PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Subcutaneous: EmphysemaDocument70 pagesSubcutaneous: EmphysemaWer TeumeNo ratings yet

- ColostomyDocument45 pagesColostomydrqiekiNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Surgery Day 1Document267 pagesPediatric Surgery Day 1ironbuangNo ratings yet

- 2017 Bone Modifying Agents in Met BC Slides - PpsDocument14 pages2017 Bone Modifying Agents in Met BC Slides - Ppsthanh tinh BuiNo ratings yet

- OsteosarkomaDocument2 pagesOsteosarkomaLinawati DLNo ratings yet

- ANATOMI ColorectalDocument16 pagesANATOMI ColorectalShannonCPMNo ratings yet

- Akses Vena Central: Anestesiologi Dan Reanimasi RSUD TasikmalayaDocument28 pagesAkses Vena Central: Anestesiologi Dan Reanimasi RSUD TasikmalayaSaeful AmbariNo ratings yet

- Early Detection and Management Colorectal CancerDocument59 pagesEarly Detection and Management Colorectal CancerAbduh BIKNo ratings yet

- Skull Cervical X-RayDocument15 pagesSkull Cervical X-RayAwal AlfitriNo ratings yet

- Wound de His Cence FinalDocument26 pagesWound de His Cence Finaldanil armandNo ratings yet

- Trauma BuliDocument32 pagesTrauma BulimoonlightsoantaNo ratings yet

- Principles of Management of Soft Tissue SarcomaDocument33 pagesPrinciples of Management of Soft Tissue Sarcomabashiruaminu100% (1)

- MESSDocument9 pagesMESStaufik sofistiawanNo ratings yet

- Anal Stenosis and Mucosal EctropionDocument7 pagesAnal Stenosis and Mucosal EctropionpologroNo ratings yet

- Bladder Substitution and Urinary DiversionDocument58 pagesBladder Substitution and Urinary DiversionlifespotNo ratings yet

- Chronic Limb IschemiaDocument29 pagesChronic Limb IschemiaSadia NaveedNo ratings yet

- Nervus Laryngeus RecurrensDocument5 pagesNervus Laryngeus RecurrensAri Julian SaputraNo ratings yet

- HypospadiaDocument45 pagesHypospadiaMartha P100% (1)

- CURRENT STATUS of HAL-RAR (Haemorrhoids Casee and Treatment in Indonesia) Prof - Dr.dr. Ing - Riwanto, SPB-KBDDocument43 pagesCURRENT STATUS of HAL-RAR (Haemorrhoids Casee and Treatment in Indonesia) Prof - Dr.dr. Ing - Riwanto, SPB-KBDHengky TanNo ratings yet

- Systemic Therapies of CRC: Johan KurniandaDocument56 pagesSystemic Therapies of CRC: Johan KurniandaANISA RACHMITA ARIANTI 2020No ratings yet

- Chest TubeDocument8 pagesChest TubeTaufik Nur YahyaNo ratings yet

- Torsio Testis2016Document6 pagesTorsio Testis2016Patrico Rillah SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Acute Abdomen and PeritonitisDocument17 pagesAcute Abdomen and PeritonitisAnisaPratiwiArumningsihNo ratings yet

- Breast Cancer: Katherine Macgillivray & Melissa PoirierDocument62 pagesBreast Cancer: Katherine Macgillivray & Melissa PoirierJonathan Darell WijayaNo ratings yet

- The Surgical Anatomy of The Nerve Laryngeal RecurrensDocument2 pagesThe Surgical Anatomy of The Nerve Laryngeal RecurrensvaNo ratings yet

- Rangkuman Salter Bab 14Document64 pagesRangkuman Salter Bab 14Febee NathaliaNo ratings yet

- Colonoscopy CecilDocument14 pagesColonoscopy Cecilyaba100% (1)

- U04 Fxs of Humeral ShaftDocument88 pagesU04 Fxs of Humeral Shaftadrian_mogosNo ratings yet

- Tokyo Guidelines 2018 Flowchart For The Management of Acute CholecystitisDocument43 pagesTokyo Guidelines 2018 Flowchart For The Management of Acute Cholecystitisfranciscomejia14835No ratings yet

- 2010 TNM Staging Colorectal CADocument2 pages2010 TNM Staging Colorectal CAbubbrubb20063998No ratings yet

- Tracheostomy: Berlian Chevi A. 20184010030Document26 pagesTracheostomy: Berlian Chevi A. 20184010030Berlian Chevi e'Xgepz ThrearsansNo ratings yet

- PCNDocument3 pagesPCNAzirah TawangNo ratings yet

- Intestinal Stomas - AKTDocument49 pagesIntestinal Stomas - AKTTammie YoungNo ratings yet

- Distribusi Patah Tulang Panjang TerbukaDocument73 pagesDistribusi Patah Tulang Panjang TerbukaCininta Anisa SavitriNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Classification of Urethral InjuriesDocument13 pagesDiagnosis and Classification of Urethral Injuriesleo100% (2)

- Oeis SyndromeDocument9 pagesOeis SyndromeADEENo ratings yet

- Cystostomy NewDocument32 pagesCystostomy Newkuncupcupu1368No ratings yet

- Colonic Volvulus: Disusun Oleh: Dhea Faizia Tasya (2110221036) Pembimbing: Dr. Yulia Rachmawati, Sp. Rad (K)Document25 pagesColonic Volvulus: Disusun Oleh: Dhea Faizia Tasya (2110221036) Pembimbing: Dr. Yulia Rachmawati, Sp. Rad (K)Dhea Faizia TasyaNo ratings yet

- Stenosing Tenosynovitis, (Trigger Finger) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandStenosing Tenosynovitis, (Trigger Finger) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- 1543 2742 Article p13Document8 pages1543 2742 Article p13Yohana Elisabeth GultomNo ratings yet

- Platelet To Lymphocyte Ratio As A Potential.27Document8 pagesPlatelet To Lymphocyte Ratio As A Potential.27Yohana Elisabeth GultomNo ratings yet

- Prognostic Markers Compared To CD3 TIL in Locally.83Document7 pagesPrognostic Markers Compared To CD3 TIL in Locally.83Yohana Elisabeth GultomNo ratings yet

- 2020 ESC Guidelines On Sports Cardiology and Exercise in Patients With Cardiovascular DiseaseDocument80 pages2020 ESC Guidelines On Sports Cardiology and Exercise in Patients With Cardiovascular DiseaseKlaraNo ratings yet

- Modern Aspects of Burn Injury ImmunopathogenesisDocument12 pagesModern Aspects of Burn Injury ImmunopathogenesisYohana Elisabeth GultomNo ratings yet

- Please Take This Boarding Pass To The Airport For Your IghtDocument1 pagePlease Take This Boarding Pass To The Airport For Your IghtYohana Elisabeth GultomNo ratings yet

- J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle - 2022 - Paval - A Systematic Review Examining The Relationship Between Cytokines and CachexiaDocument15 pagesJ Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle - 2022 - Paval - A Systematic Review Examining The Relationship Between Cytokines and CachexiaYohana Elisabeth GultomNo ratings yet

- Handout - 2!22!22 Nutrition Implication On Long Covid ASPENDocument54 pagesHandout - 2!22!22 Nutrition Implication On Long Covid ASPENYohana Elisabeth GultomNo ratings yet

- Inflammation Marker and Micronutrient DeficiencyDocument19 pagesInflammation Marker and Micronutrient DeficiencyYohana Elisabeth GultomNo ratings yet

- Hypocalcemia: Michelle Sergel (PDocument15 pagesHypocalcemia: Michelle Sergel (PYohana Elisabeth GultomNo ratings yet

- Hypocalcemia Pada Beta Thalassemia PDFDocument3 pagesHypocalcemia Pada Beta Thalassemia PDFYohana Elisabeth GultomNo ratings yet

- Bladder: Male Urethra and Its SegmentsDocument33 pagesBladder: Male Urethra and Its SegmentsYohana Elisabeth GultomNo ratings yet

- PeritonitisDocument9 pagesPeritonitismardsz100% (4)

- Essay Sex AbuseDocument4 pagesEssay Sex AbuseFang KenNo ratings yet

- Psychoimmunology Essay by DR Romesh Senewiratne-Alagaratnam (MD)Document32 pagesPsychoimmunology Essay by DR Romesh Senewiratne-Alagaratnam (MD)Dr Romesh Arya Chakravarti100% (2)

- An Alternative Impression Technique For Mobile TeethDocument25 pagesAn Alternative Impression Technique For Mobile TeethmujtabaNo ratings yet

- CaDocument10 pagesCaShielany Ann Abadingo100% (1)

- Diet Readiness QuestionnaireDocument3 pagesDiet Readiness Questionnairesavvy_as_98100% (1)

- ATLSDocument22 pagesATLSHemant Khambhati78% (9)

- Obesity: Differential DiagnosisDocument0 pagesObesity: Differential Diagnosisrasputin22100% (1)

- Medical EthicsDocument27 pagesMedical Ethicspriyarajan007No ratings yet

- Cerebral Aneurysm FINALDocument33 pagesCerebral Aneurysm FINALkanejasper0% (2)

- Surgical TechniqueDocument52 pagesSurgical TechniqueKutub SikderNo ratings yet

- Atlas of Abdominal Wall ReconstructionDocument14 pagesAtlas of Abdominal Wall ReconstructionEmmanuel BarriosNo ratings yet

- b2 CoolDocument2 pagesb2 CoolGanesh kumarNo ratings yet

- Oral and Maxillofacial PathologyDocument79 pagesOral and Maxillofacial PathologyMai AnhNo ratings yet

- Viaro 2022 - 2Document8 pagesViaro 2022 - 2moikaufmannNo ratings yet

- Formulir Klaim Rawat InapDocument2 pagesFormulir Klaim Rawat InapGoris DonkeyNo ratings yet

- Inhaled Budesonide in The Treatment of Early COVID-19Document10 pagesInhaled Budesonide in The Treatment of Early COVID-19Dusan OrescaninNo ratings yet

- Xanax Drug CardDocument3 pagesXanax Drug Cardnasir khanNo ratings yet

- HKG - Exercise Prescription (Doctor's Handbook)Document126 pagesHKG - Exercise Prescription (Doctor's Handbook)Chi-Wa CWNo ratings yet

- Roleplay FastfoodDocument9 pagesRoleplay FastfoodIndra DarmaNo ratings yet

- IE Humeral Neck FractureDocument9 pagesIE Humeral Neck FractureEarll Justin N. DataNo ratings yet

- Case Study 2Document3 pagesCase Study 2Thesa Ray PadernalNo ratings yet

- OT RotationDocument5 pagesOT RotationAnnbe BarteNo ratings yet

- NCM 100 - Lecture Final ExaminationDocument4 pagesNCM 100 - Lecture Final ExaminationjafcachoNo ratings yet

- Cardiogenic Brain Abscess in ChildrenDocument28 pagesCardiogenic Brain Abscess in ChildrenDina MarselinaNo ratings yet

- NUR 450 Unit 3 Exam Blueprint Summer 2019 LIU UniversityDocument2 pagesNUR 450 Unit 3 Exam Blueprint Summer 2019 LIU UniversityMohammad Malik100% (1)

- English For ChemistryDocument53 pagesEnglish For ChemistryNoah FathiNo ratings yet

- 21 FoodImpaction 20150102105737 PDFDocument4 pages21 FoodImpaction 20150102105737 PDFDina NovaniaNo ratings yet

- Diabetes InsipidusDocument2 pagesDiabetes InsipidusLuiciaNo ratings yet