Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Absolute Priority Rule Violations in Bankruptcy

Uploaded by

vidovdan9852Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Absolute Priority Rule Violations in Bankruptcy

Uploaded by

vidovdan9852Copyright:

Available Formats

21

Absolute Priority Rule

Violations in Bankruptcy

by Stanley D. Longhofer and

Charles T. Carlstrom

Stanley D. Longhofer and Charles

T. Carlstrom are economists at the

Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

Introduction

Any transacti on i nvolvi ng a conti nui ng relati on-

shi p over ti me dependson a mechani sm by

whi ch parti escan commi t themselvesto some

future behavi or. Thi soften i nvolveswri ti ng con-

tracts. I n most cases, we depend on govern-

ment to enforce these contractsthrough a court

system. I ndeed, one of governmentsmost i m-

portant rolesi n any economy i sdefi ni ng and

enforci ng pri vate property ri ghts. Si nce contracts

are si mply a meansof transferri ng pri vate prop-

erty, the use of courtsto enforce them hasa

certai n logi cal appeal.

Loan agreementsare one of the most com-

mon typesof contractsi n our economy. Lenders

agree to i nvest i n a busi nessand the ownersof

that busi nessagree to repay the loan, wi th i nter-

est, at some future date. I f the borrower fai lsto

repay the loan, hi scredi torsmay force hi m i nto

bankruptcy and sei ze hi sassets. By defi ni ti on,

debt contractsrequi re that credi torsbe pai d

before the fi rmsownersrecei ve any value. I n

other words, credi torsare assumed to have

pri ori ty over a fi rmsequi ty holders.

Thi spri nci ple i sknown asthe absolute pri or-

i ty rule ( APR) . Si mply stated, thi srule requi res

that the debtor recei ve no value from hi sassets

unti l all of hi scredi torshave been repai d i n

full.

1

Whi le thi srule would seem qui te si mple

to i mplement, i t i srouti nely ci rcumvented i n

practi ce. I n fact, bankruptcy courtsthemselves

play a major role i n abrogati ng thi sfeature of

debt contracts. I f pri vate loan contractsare

entered i nto voluntari ly, why do courtsallow

( and even encourage) thei r termsto be vi olated

on a regular basi s?More i mportant, what i mpact

do these vi olati onshave on the cost of fi nanci al

contracti ng and, hence, economi c effi ci ency?

Thi sarti cle addressesthese questi onsby

analyzi ng the i mpact of APR vi olati onson

fi nanci al contracts. We begi n i n the next secti on

by revi ewi ng the magni tude of these vi olati ons

and the frequency wi th whi ch they occur. I n

secti on I I , we develop a si mple model to ana-

lyze the effi ci ency of APR vi olati ons. We com-

pli cate thi smodel wi th several market fri cti ons

to show how the i mpact of these vi olati ons

dependson whi ch fri cti on i spresent. Secti on

I I I di scussesthe modelsi mpli cati onsfor the

proper role of bankruptcy law i n enforci ng

these contracts. Secti on I V concludes.

I 1 The APR al so states that seni or credi tors shoul d be pai d before

j uni or credi tors. In thi s paper, we consi der onl y APR vi ol ati ons between the

borrower and a (si ngl e) l ender.

22

I. The Prevalence

of APR Violations

A growi ng body of empi ri cal evi dence supports

the conclusi on that APR vi olati onsare common-

place both i n Chapter 11 reorgani zati onsand i n

i nformal workouts. Usi ng di fferent samplesof

large corporati onswi th publi cly traded securi -

ti es, numerousresearchershave found that

equi ty holdersrecei ve value from fi nanci ally

di stressed fi rmsi n vi olati on of the APR i n nearly

75 percent of all reorgani zati ons.

2

Thi sappears

to be true whether one looksat pri vate, i nfor-

mal workouts, conventi onal reorgani zati ons, or

prepackaged bankruptci es i n whi ch the detai ls

of the reorgani zati on are negoti ated before the

bankruptcy peti ti on hasbeen fi led.

The frequency wi th whi ch APR vi olati ons

occur mi ght be mi sleadi ng i f the magni tude of

these devi ati onsasa percentage of the fi rms

value were relati vely small. I ndeed, some com-

mentatorshave suggested that value pai d to

equi ty i ssi mply a token to speed up the process

and hasli ttle economi c si gni fi cance: Sharehold-

erswere tossed a bone, crumbsoff the table, to

get the deal done...

3

Exi sti ng evi dence, how-

ever, suggeststhat thi si snot generally the case.

Esti matesof the magni tude of APR vi olati onsi n

favor of equi ty vary, but i n reorgani zati onsi n

whi ch such vi olati onsoccur, equi ty holders

appear to recei ve between 4 and 10 percent of

the fi rmsvalue.

4

And although the evi dence i s

limited, some have suggested that these devia-

tionsare larger for small firmswhose owners

I 2 See Franks and Torous (1989), LoPucki and Whi tford (1990),

Wei ss (1990), Eberhart, Moore, and Roenfel dt (1990), and Betker (1995).

I 3 Quoted i n Wei ss (1990), p. 294.

I 4 See Eberhart, Moore, and Roenfel dt (1990), Franks and Torous

(1994), Tashj i an, Lease, and McConnel l (1996), and Betker (1995). Franks

and Torous note that the l arger devi ati ons found by Eberhart, Moore, and

Roenfel dt may be a consequence of the l atters ol der sampl e of di stressed

fi rms: Wi th the growth i n the market for di stressed debt securi ti es and the

greater i nvol vement of i nsti tuti onal i nvestors such as vul ture funds,

debthol ders may have i ncreased thei r bargai ni ng power at the expense of

equi ty hol ders (Franks and Torous [ 1994] , p. 364).

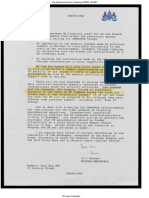

T A B L E 1

Empirical Research

on APR Violations

Article Data Dates Frequency Magnitude

Franksand Torous( 1989) 30 fi rmswi th publi cly traded 197084 66.67%

debt fi li ng for bankruptcy

LoPucki and Whi tford 43 fi rmswi th more than 197988 48.84%

( 1990) $100 mi lli on i n assetsand

at least one publi cly traded

securi ty under Chapter 11

Eberhart, Moore, and 30 fi rmswi th publi cly traded 197986 76.67% 7.57%

Roenfeldt ( 1990) stock under Chapter 11

Wei ss( 1990) 37 NY SE and AMEX fi rms 198086 72.97%

under Chapter 11

Franksand Torous( 1994) 82 fi rmswi th publi cly traded 198390 9.51% workouts

debt under Chapter 11 or an 2.28% Chapter 11

i nformal workout

Tashji an, Lease, and 48 fi rmswi th a publi cly traded 198093 72.92% 1.59%

McConnell ( 1996) securi ty or more than $95 mi lli on

i n assets, reorgani zi ng wi th a

prepackaged bankruptcy

Betker ( 1995) 75 fi rmswi th publi cly traded 198290 72.00% 2.86%

securi ti esunder Chapter 11

SO URCE: Authors revi ew of the li terature.

23

also manage the company.

5

Table 1 summarizes

recent empirical research on APR violations.

O ne major caveat should be kept i n mi nd

when consi deri ng these fi ndi ngs: All the stud-

i esof bankruptcy resoluti on ci ted here have

focused on fi rmswi th publi cly traded stock

and/or debt.

6

However, such fi rmscompri se

only a small subset of those fi li ng for Chapter 11

bankruptcy or i ni ti ati ng out-of-court debt work-

outs. Asa result, the number of fi rmsi ncluded

i n these studi esaverageslessthan 50. I n con-

trast, there were over 176,000 Chapter 11 cases

fi led nati onwi de i n the fi rst 10 yearsafter the

new Bankruptcy Code wasi mplemented i n

1979 ( Flynn [1989]) . Even after eli mi nati ng

si ngle-asset real estate partnershi psand house

fi li ngsto focuson what mi ght reasonably be

consi dered true busi ness reorgani zati ons,

these studi eshave depressi ngly small and

bi ased samplesof average reorgani zati ons.

7

I ndeed, bankruptcy judge Li sa Fenni ng notes

that only fi ve out of more than 600 Chapter 11

caseson her docket i nvolve publi cly traded

compani es.

8

Clearly, we must be cauti ousand

avoi d overi nterpreti ng these empi ri cal studi es.

II. APR Violations

and Efficiency

Many have argued that APR vi olati onsoccur be-

cause they are pri vately opti mal for bankruptcy

parti ci pants. I f stri ct adherence to the APR cre-

atesperverse i nvestment i ncenti vesonce the

fi rm i si n bankruptcy, i t may be pri vately opti -

mal ( ex post) for everyone i nvolved to abrogate

such rulesand renegoti ate thei r contracts.

9

Under thi svi ew, APR vi olati ons both i nsi de

Chapter 11 and i n out-of-court workouts are

a desi rable consequence of renegoti ati on be-

tween the fi rm and i tscredi tors; APR vi olati ons

are essenti ally payoffsby lendersto encourage

the fi rmsshareholdersto make good i nvest-

ment deci si onsonce the fi rm i si n fi nanci al di s-

tress. Unfortunately, thi svi ew fai lsto take i nto

account how such behavi or affectsex ante effi -

ci ency through the termsof the ori gi nal fi nan-

ci al contract, whi ch i sulti mately the only way to

evaluate the effi ci ency of APR vi olati onsfully.

To focuson thi sproblem, we develop a si m-

ple model of fi nanci al contracti ng. Consi der an

entrepreneur who wantsto open a fi rm and i n-

vest i n a project, but needsto borrow I dollars

from an outsi de i nvestor to do so. I n return for

thi sloan, the entrepreneur agreesto repay hi s

lender R dollarsfrom hi sfi rmsfuture profi t.

For ease of exposi ti on, we wi ll often refer to

Rasthe i nterest rate.

10

O f course, the fi rms

profi t i snot guaranteed. Let x denote the fi rms

reali zed profi t, whi ch can take valueson the

i nterval [

x,

x]. Let f ( x) be the probabi li ty that

any gi ven x i sreali zed ( that i s, i tsprobabi li ty

densi ty functi on) and, asi sstandard, let F( x) be

the associ ated di stri buti on functi on. To model

APR vi olati ons, let represent the fracti on of

the fi rmsprofi t retai ned by the entrepreneur i n

bankruptcy.

The entrepreneur wi ll default whenever do-

i ng so gi veshi m a hi gher return ( that i s, when-

ever x R< x) . Defi ne x

= R/( 1 ) asthe

cri ti cal level of profi t below whi ch default

occurs. The entrepreneursexpected return

from hi sbusi ness, E, i sthen:

( 1) E =

x

xf (x) dx+

x

( x R) f ( x) dx.

When bankruptcy occurs, the entrepreneur

recei vesonly fracti on of the fi rmsprofi t x;

by wei ghti ng thi sby f ( x) and i ntegrati ng over

all levelsof profi t for whi ch default occurs, we

obtai n the fi rst term i n E. O n the other hand,

when the fi rmsprofi t exceedsx

, the entrepre-

neur usesi t to repay hi sloan and keepsthe

rest. Wei ghti ng thi sby f ( x) and i ntegrati ng over

all x > x

gi vesusthe second term i n E.

I n a competi ti ve lendi ng market, the equi li b-

ri um i nterest rate, R*, i sset to ensure that the

lender i sjust wi lli ng to make the loan:

11

( 2) L =

x*

x

( 1 ) xf ( x) dx +

x*

R*f (x) dx I = 0.

Asabove, the fi rst term i n thi sexpressi on

representsthe lendersexpected return when

I 5 See LoPucki (1983) and LoPucki and Whi tford (1990).

I 6 LoPucki (1983) i s an excepti on.

I 7 House fi l i ngs are Chapter 11 fi l i ngs by i ndi vi dual s whose home

mortgages exceed the Chapter 13 debt l i mi t. The 1994 changes to the

Bankruptcy Code shoul d make such fi l i ngs l ess common.

I 8 Fenni ng (1993).

I 9 See Bul ow and Shoven (1978), Whi te (1980, 1983), Gertner and

Scharfstei n (1991), and Berkovi tch and Israel (1991) for model s that pro-

mote thi s i dea.

I 10 Techni cal l y, R i s the face val ue of the debt and i s equal to

(1 + r ) I , where r i s the nomi nal i nterest rate on the l oan.

I 11 Implicit in this specification is the assumption that the competi-

tive return on riskless assets is 1, so that the lenders cost of funds is only I.

24

default occurs, and i sthe fi rmsprofi t i n these

statesmi nusthe APR vi olati on. The second

term i n L followsfrom the fact that the lender

i ssi mply pai d R* i n all nondefault states.

I n thi ssi mple model, APR vi olati onshave no

i mpact on the fi rmscost of fi nanci ng. Whi le i t i s

true that once the fi rm i si n bankruptcy the en-

trepreneur i sbetter off wi th large APR vi ola-

ti ons, these gai nsare enti rely offset by i ncreases

i n the i nterest rate the fi rm i sforced to pay. To

see thi s, we substi tute the equi li bri um soluti on

for R i nto ( 1) to get

( 3) E =

x

xf (x) dx I .

The fact that doesnot appear i n thi sex-

pressi on showsusthat the fi rmsprofi t i sunaf-

fected by the si ze of the APR vi olati on.

12

I n thi ssi mple model, the magni tude of APR

vi olati onshasno i mpact on the cost of the i ni -

ti al fi nanci al contract. O f course, thi sanalysi s

i gnoresmany of the problemsthat plague real-

world fi nanci al contracti ng. Throughout the rest

of thi ssecti on, we extend thi smodel wi th sev-

eral standard compli cati onsand show how the

effect of APR vi olati onsdependson whi ch

problem i spresent.

Costly Bankruptcy

One of the most basi c problemsi n fi nanci al

contracti ng i sthe fact that bankruptcy i scostly.

Let c denote the cost pai d by the lender when-

ever he forcesthe entrepreneur i nto bankruptcy

( for si mpli ci ty, assume c < x

) .

13

Asbefore, the

equi li bri um i nterest rate, R*, must be set to en-

sure that the lender earnsa competi ti ve return:

( 4) L =

x*

x

[ ( 1 ) x c] f ( x) dx

+

x*

R*f (x) dx I = 0.

I n the appendi x, we veri fy that, asbefore, i n-

creasesi n the magni tude of the APR vi olati on

make default more li kely ( that i s, dx */d > 0) .

Substi tuti ng ( 4) i nto the entrepreneurs

expected profi t ( 1) , we get

( 5) E =

x

xf (x) dx I cF( x *) .

Thi sexpressi on demonstrateshow APR vi ola-

ti onsaffect the termsof the loan agreement.

Si nce x

* i ncreaseswi th , larger APR vi olati ons

make bankruptcy occur more frequently. Asa

result, the added expected bankruptcy costs,

cF ( x

*) , lower the entrepreneursex ante

expected return.

I n thi senvi ronment, APR vi olati onsmay cre-

ate an addi ti onal problem. Although the lenders

expected return i sgenerally i ncreasi ng i n the i n-

terest rate, eventually the added expected bank-

ruptcy costsassoci ated wi th hi gher i nterest rates

outwei gh thei r benefi ts; that i s, L wi ll eventually

be decreasi ng i n R. Wi lli amson ( 1986) shows

that thi seffect can lead to credi t rati oni ng, si nce

changesi n the i nterest rate may be i nsuffi ci ent

to clear the loan market.

I ncreasesi n the magni tude of APR vi olati ons

have the same i mpact: By reduci ng the lenders

payoff i n default statesand i ncreasi ng the prob-

abi li ty that bankruptcy wi ll occur, a poi nt

comesat whi ch the lender can no longer be

compensated for addi ti onal vi olati onsof the

APR through i ncreasesi n the i nterest rate. I n

other words, APR vi olati onsexacerbate credi t-

rati oni ng problems.

Thus, when bankruptcy i scostly, there are

strong reasonsto avoi d APR vi olati ons. Fi rst,

these vi olati onsrai se the i nterest rate the entre-

preneur must pay, i ncreasi ng the chance that

default and i tscorrespondi ng costs wi ll

occur. Furthermore, vi olati onsmake credi t

rati oni ng more li kely, thereby li mi ti ng the

entrepreneursi nvestment opportuni ti es. Why,

then, do they occur wi th such frequency?We

next turn to one possi ble reason.

Asymmetric

Liquidation

Value

The model presented above assumesthat the

fi rm had no capi tal assetsonce the project was

completed or, alternati vely, that the fi rm had no

goi ng-concern value. But much of the justi fi -

cati on for a reorgani zati on procedure deri ves

from the beli ef that many fi rmsi n fi nanci al di s-

tressare i n fact economi cally vi able and should

be reorgani zed rather than li qui dated.

14

To focuson thi si dea, we return to our ori gi -

nal model ( i n whi ch bankruptcy i scostless) and

si mpli fy i t by assumi ng that only two levelsof

I 12 On the other hand, APR vi ol ati ons can l ead to credi t- rati oni ng

probl ems, even i n thi s si mpl e model , si nce they make defaul t occur more

frequentl y. We di scuss thi s probl em i n the subsecti on that fol l ows.

I 13 Thi s, then, i s the costl y state veri fi cati on envi ronment devel oped

by Townsend (1979) and Gal e and Hel l wi g (1985).

I 14 Harri s and Ravi v (1993) devel op a model based on thi s i ssue

and come to si mi l ar concl usi ons.

25

profi t are possi ble. I n good statesof the world,

whi ch occur wi th probabi li ty , the entrepre-

neursbusi nessearnsxH. I n contrast, when

busi nessi sbad, the fi rm earnsonly xL; thi soc-

curswi th probabi li ty ( 1 ) . Furthermore,

assume that when busi nessi sgood the entre-

preneur can repay hi sdebt, but i n bad stateshe

cannot; that i s, xH > R> xL.

I n addi ti on to i tsprofi t, x, the fi rm hascapi -

tal assetsworth A once i tsproject i scompleted;

these can be thought of asthe value of the

fi rmsexpected future profi t. I f thi svalue i sthe

same regardlessof who ownsthe fi rm, our

resultsremai n unchanged: APR vi olati onshave

no i mpact on the termsof the fi nanci al con-

tract. O n the other hand, i f the fi rmsassetsare

worth more i n the handsof the entrepreneur,

there wi ll be an i ncenti ve to modi fy the fi nan-

ci al contract to allow hi m to retai n control of

the fi rm even after fi li ng for bankruptcy.

Let represent the fracti on of the fi rms

assets( and hence future profi t) retai ned by the

entrepreneur duri ng bankruptcy. I n thi scase,

the entrepreneursexpected profi t

15

i s

( 6) E = ( 1 ) ( xL + A) + ( xH R + A) .

Let be the fracti on of the fi rmsongoi ng

value that i slost by transferri ng these assetsto

the lender. O nce agai n, the equi li bri um i nterest

rate must be set to guarantee the lender a com-

peti ti ve return:

( 7) L = ( 1 ) [( 1 ) xL + ( 1 ) A]

+ R* I = 0.

Substi tuti ng thi si nto the entrepreneurs

expected profi t gi vesus

( 8) E = ( 1 ) ( xL + A) + ( xH + A)

+ ( 1 ) ( 1 ) ( 1) A I .

Asbefore, i t i si rrelevant whether the entre-

preneur i sallowed to keep some of the profi t

( the si ze of ) when the fi rm defaults; the i nter-

est rate adjustsso asto keep the entrepreneurs

expected return unchanged. Li kewi se, when

= 1 and the fi rmscapi tal assetshave the same

value regardlessof who controlsthem, the si ze

of doesnot matter; that i s, APR vi olati ons

i nvolvi ng the fi rmscapi tal assetsare i rrelevant.

I n thi scase, we are back to our ori gi nal model.

Noti ce, however, that the same i snot true

when i slessthan one. Di fferenti ati ng ( 8)

wi th respect to gi vesus

( 9)

d

d

E

=( 1 ) ( 1 ) A > 0;

si nce these assetsare worth lessto the lender

than they are to the entrepreneur, APR vi ola-

ti onsof thi ssort are benefi ci al.

Why are both and necessary to analyze

the i mpact of APR vi olati onsi n thi senvi ron-

ment?The i ntui ti on i sclear: APR vi olati onsare

benefi ci al only when they are appli ed to A,

si nce thi si sthe only part of the fi rmsvalue

that i sworth more i n the handsof the entre-

preneur. I f allowi ng the lender to keep some

of x

L

hasany detri mental i mpact ( such as

costly bankruptcy) , the desi rabi li ty of di sti n-

gui shi ng between these two typesof APR vi o-

lati onsi sobvi ous.

O ne mi ght wonder whether there i sa practi -

cal di sti ncti on between x

L

and A. For large,

publi cly traded fi rms, thi sdi sti ncti on may be

i rrelevant. After all, the goi ng-concern value of

Johnson & Johnson i sli kely to be unaffected by

the i denti ty of i tsstockholders( that i s, thei r i s

equal to one) . O n the other hand, fi rmsthat are

owned and managed by an entrepreneur who

bri ngsspeci ali zed ski llsto hi scompany are

li kely to have small s. I n thi scase, i t mi ght be

reasonable to allow the entrepreneur to keep

control of hi sfi rm after bankruptcy, but all of

the fi rmsli qui d assetsshould be transferred to

i tscredi tors.

Risk Shifting

Perhapsthe most common problem i n fi nanci al

contracti ng i sthe borrowersi ncenti ve to under-

take acti onsthat affect the ri ski nessof hi sbusi -

ness.

16

Suppose that, by exerti ng effort, the

entrepreneur can affect the li keli hood that the

fi rm wi ll be successful. I f the entrepreneur

workshard, the fi rm wi ll earn x

H

wi th proba-

bi li ty

1

; wi thout effort, i t wi ll earn x

H

wi th

probabi li ty

2

<

1

. I n addi ti on, assume that the

amount of effort requi red ( or alternati vely, the

cost of thi seffort) i snot di scovered unti l after

the loan i smade; let e represent the effort ulti -

mately requi red. Fi nally, suppose that the lender

cannot observe whether effort i sexerted.

After learni ng the effort requi red, the entre-

preneursexpected return from the good

project i s( 1

1

) x

L

+

1

( x

H

R) e, whi le

hi sexpected return from the bad project i s

( 1

2

) x

L

+

2

( x

H

R) . Ulti mately, whether

I 15 Thi s expressi on i s anal ogous to equati on (1); note that we have

assumed onl y two possi bl e states of the worl d.

I 16 Bebchuk (1991) devel ops a di fferent model of ri sk shi fti ng and

comes to si mi l ar concl usi ons. See al so Innes (1990).

26

the entrepreneur choosesto undertake the

good project ( that i s, exert effort) wi ll depend

on how much effort i srequi red. He wi ll select

the good project aslong ashi sreali zed e i sless

than e*, where

( 10) e* = ( 1 2) ( xH R xL) .

I n what follows, i t wi ll be useful to know

how often the entrepreneur wi ll select the

good project, whi ch requi resusto know the

di stri buti on of e. Assume for si mpli ci ty that

ei sdi stri buted uni formly on the i nterval [0,1].

I n thi scase, the probabi li ty that the entrepre-

neur wi ll choose the good project ( that i s, that

e < e*) i ssi mply e*.

The lender, knowi ng that the entrepreneur

wi ll choose the good project wi th probabi li ty e*

and the bad project wi th probabi li ty 1 e*, wi ll

demand an i nterest rate that guaranteeshi m

zero expected profi t:

( 11) L = [e*( 1 1) + ( 1 e*) ( 1 2) ]( 1 ) xL

+ [e*1 + ( 1 e*) 2]R* I = 0.

Before he takesthe loan, the entrepreneurs

expected return i ssi mply hi sexpected profi t

from each of the projects, wei ghted by the

probabi li ty that he wi ll choose each, mi nushi s

expected effort condi ti onal on the good project

bei ng chosen:

( 12) E = ( 1 e*) [2( xH R) + ( 1 2) xL]

+ e*[1( xH R) + ( 1 1) xL]

e

2

*

2

.

Substi tuti ng R* i nto thi sexpressi on gi vesus:

( 13) E = e*( 1 2) ( xH xL) + 2 xH

+ ( 1 2) xL

e

2

*

2

I.

Asi n our ori gi nal problem, hasno di rect

effect on the entrepreneursex ante expected

return; the i nterest rate si mply adjuststo ensure

that the lender makesa competi ti ve return. O n

the other hand, such APR vi olati onsdo have an

i ndi rect effect through thei r i mpact on the

probabi li ty that the entrepreneur wi ll exert

effort and choose the good project. Di fferenti at-

i ng ( 13) wi th respect to yi elds

( 14)

d

d

d

d

e

[( 1 2) ( xH xL) e*]

=

d

d

e

( 1 2) [R ( 1 ) xL].

Now, R > ( 1 ) x

L

by assumpti on. I n the

appendi x, we demonstrate that de*/d 0,

that i s, that the presence of large APR vi olati ons

makesthe entrepreneur lessli kely to choose

the good project.

17

Combi ni ng these results

showsthat the entrepreneursexpected profi t i s

decreasi ng i n . Hence, when ri sk shi fti ng i sa

problem, APR vi olati onsare ex ante i neffi ci ent.

The i ntui ti on behi nd thi si sstrai ghtforward.

Asbefore, the di rect benefi t to the entrepreneur

of recei vi ng compensati on when the fi rm fai ls

i sexactly offset by the hi gher i nterest rate he

must pay.

18

O n the other hand, APR vi olati ons

reduce the entrepreneursi ncenti ve to under-

take the good project. Why i sthi sthe case?

Si nce effort i scostly for the entrepreneur, he

would li ke to avoi d i t whenever possi ble. Nev-

ertheless, he i swi lli ng to exert some effort,

si nce doi ng so makesi t more li kely that the

fi rm wi ll be successful, reapi ng hi m a hi gher

return. The presence of these vi olati ons, how-

ever, reducesthe pai n of bankruptcy and hence

the relati ve benefi tsof thi seffort. After all, why

should the entrepreneur work hard i f he can be

assured of a si zable payoff even when hi sbusi -

nessbombs?Asa result, the entrepreneur

exertslesseffort than he would i f there were

no APR vi olati ons.

III. Policy Implications

The resultsof the last secti on suggest that an

opti mal bankruptcy i nsti tuti on would allow

debtorsand credi torsto deci de ex ante

whether APR vi olati onswi ll occur. I n other

words, the parti esto the loan agreement should

be allowed to wri te a contract that speci fi es

under what condi ti onsAPR vi olati onswi ll and

wi ll not occur.

Although the desi rabi li ty of such a system

mi ght seem obvi ous, current bankruptcy law

doesnot enforce agreementsli ke these. O nce a

fi rm entersbankruptcy, i t must follow the rules

and proceduresset out i n the Bankruptcy

Code, and no one i sallowed to forfei t hi s

future ri ght to fi le for bankruptcy when he

si gnsa loan agreement. Thi smi ght not be a

problem i f i t werent for the fact that current

bankruptcy law strongly encouragesAPR vi ola-

ti ons, regardlessof whether they are effi ci ent.

I 17 For smal l , d e* / d may be zero; i n thi s range, the payments

that the entrepreneur recei ves i n bankruptcy are not l arge enough to di s-

courage hi m from choosi ng the good proj ect, regardl ess of the l evel of

effort requi red.

I 18 Once agai n, however, a credi t- rati oni ng probl em i s possi bl e.

27

Several featuresof the code make thi strue.

Fi rst, the debtor retai nscontrol of the fi rm

throughout the process, except i n extraordi nary

ci rcumstances. Second, the debtor i sallowed to

obtai n debtor-i n-possessi on fi nanci ng to con-

ti nue operati on of the busi ness; thi sfi nanci ng i s

automati cally gi ven pri ori ty over all of the

fi rmsunsecured clai ms. Thi rd, the debtor i s

granted 120 daysto propose a plan of reorgani -

zati on; duri ng thi sti me, no other parti esmay

propose alternati ve plans.

19

Fi nally, i f the

debtorsreorgani zati on plan i snot approved by

i tscredi tors, i t may attempt to enforce a cram-

down, getti ng the judge to i mpose the plan

agai nst the credi tors wi shes.

20

Each of these

factorsgi vesthe debtor leverage i n the reorga-

ni zati on, i ncreasi ng the li keli hood ( and magni -

tude) of APR vi olati ons.

Although one mi ght appeal to asymmetri c

li qui dati on valuesasa justi fi cati on for APR vi o-

lati ons, a formal bankruptcy procedure that

mandates them seemsunwarranted, especi ally

i n li ght of other problemsthat make APR vi ola-

ti onsi neffi ci ent. After all, nothi ng preventsthe

fi rm and i tscredi torsfrom wri ti ng a loan agree-

ment that would keep the fi rmscapi tal assets

i n the entrepreneurshands, even i n default.

Thi spoi ntsout an addi ti onal compli cati on

that must be present to justi fy a speci al bank-

ruptcy law: i ncomplete contracti ng. I f the future

value of the firmscapital assetsisuncertain, and

the entrepreneur and the lender cannot agree

on a way to measure i tsvalue, some outsi de

arbi ter may be useful. Whi le bankruptcy courts

can certainly fill thisrole, the implicit assumption

that the contract parti ci pantscannot desi gnate

such an arbi ter i n thei r agreement seemsex-

treme. O n the other hand, bankruptcy law may

be able to provi de a useful baseli ne to reduce

the costsof contracti ng on i mprobable events.

Potenti al confli ctsamong di fferent credi tors

mi ght provi de another justi fi cati on for bank-

ruptcy laws.

21

I n thei r rush to retri eve some

value from a fi nanci ally di stressed fi rm, the

theory goes, lendersmay i nadvertently reduce

the total value of the fi rmsassetsthat are avai l-

able for di stri buti on. Thi smi ght happen i f the

fi rmsassetsare worth more undi vi ded, but

i ndi vi dual credi torshave li enson speci fi c

assets. Worse yet, thi srush mi ght cause fi nan-

ci ally vi able fi rmsto be li qui dated. Setti ng asi de

the questi on of why the fi rm and i tscredi tors

cannot foresee these problemsand wri te thei r

contractsso asto prevent them, thi srati onale

for bankruptcy law doesnot necessari ly man-

date that i t vi olate contractual pri ori ti esthat are

determi ned ex ante.

Nonetheless, many fi rmsmay feel that the

fact-fi ndi ng and medi ati on servi cesprovi ded by

a formal bankruptcy i nsti tuti on provi de a cost-

effecti ve way of wri ti ng fi nanci al contracts. Si m-

i larly, confli ctsamong credi torsmay be suffi -

ci ently severe to justi fy the use of such an

i nsti tuti on. Asa result, one would be overzeal-

ousi n recommendi ng total repeal of the Bank-

ruptcy Code.

I t i sclear, however, that any bankruptcy pro-

cedure should merely provi de an opti onal start-

i ng poi nt for pri vate contracts. I f everyone i n-

volved fi ndsi t conveni ent to use thi si nsti tuti on,

they may. But i f they fi nd the procedure unnec-

essari ly restri cti ve, they should have the oppor-

tuni ty, when they wri te thei r fi nanci al contract,

to opt out of i t enti rely. That i s, the parti esto

the loan agreement should be allowed to deci de

up front, when they wri te thei r agreement,

whether a formal bankruptcy procedure wi ll

be used i n the event of fi nanci al di stress.

O n the one hand, small entrepreneuri al

fi rmswi th hi ghly uncertai n marketsand prod-

uctsmay fi nd Chapter 11 protecti on benefi ci al.

Asdi scussed above, Chapter 11 gi vesequi ty

substanti al bargai ni ng power i n the renegoti a-

ti on process. Si nce these fi rmsare more li kely

to benefi t from the abi li ty to recontract when

new i nformati on i savai lable, and thei r man-

agersare more li kely to possessspeci al ski lls

that affect the fi rmsgoi ng-concern value, thi s

added bargai ni ng power and the resulti ng vi o-

lati onsi n the APR are more li kely to be benefi -

ci al. Fi rmsi n thi ssi tuati on would typi cally

i nclude the ri ght to seek Chapter 11 protecti on

i n thei r debt contracts.

I n contrast, fi rmsthat have greater opportu-

ni ti esto adjust thei r acti vi ti esto the detri ment

of thei r credi torswould generally choose to opt

out of thi sprotecti on. Formally forfei ti ng thei r

ri ght to Chapter 11 protecti on would clearly

si gnal thei r credi torsof thei r i ntenti on to avoi d

hi gh-ri sk projects. Li kewi se, large, publi cly

I 19 Thi s excl usi vi ty peri od i s often extended i ndefi ni tel y (Franks and

Torous [ 1989] and LoPucki and Whi tford [ 1990] ).

I 20 Cram- downs are rather uncommon, and are al l owed onl y i n

cases i n whi ch al l di ssenti ng credi tors recei ve at l east what they are due

under the APR when the fi rm i s l i qui dated. A cram- down may nonethel ess

i mpose an APR vi ol ati on i f the fi rm woul d be worth more i f i t conti nued

than i f i t were l i qui dated, or i f the face val ue of the securi ti es offered to di s-

senti ng credi tors i s substanti al l y above thei r true market val ue. Further-

more, the threat of a cram- down, whi ch i s costl y to fi ght, may cause some

credi tors to accept l ower payouts than they mi ght otherwi se.

I 21 See Jackson (1986) for a compl ete di scussi on of thi s argument.

28

traded fi rmswhose goi ng-concern value i s

unaffected by thei r ownershi p would benefi t

from such an opti on.

IV. Conclusion

Thi spaper hasdemonstrated how the effi ci ency

of APR vi olati onsdependson the nature of the

contracti ng problem present. When the fi rms

future profi t wi ll be hi gher i f i t i scontrolled by

the entrepreneur, i t makessense for hi m to re-

tai n the fi rmscapi tal assets i f not i tspast

profi ts after bankruptcy. O n the other hand,

APR vi olati onsof any sort have the detri mental

effect of rai si ng i nterest rates, thereby i ncreas-

i ng expected bankruptcy costsand worseni ng

credi t-rati oni ng problems. Furthermore, APR

vi olati onscan reduce the entrepreneursi n-

centi ve to work hard i n order to ensure hi s

fi rmsprofi tabi li ty.

The di versi ty of these i mpli cati onssuggests

that an opti mal bankruptcy law would allow

fi rmsand thei r credi torsto deci de ex ante

whether ( and what type of) APR vi olati onswi ll

occur i n the event of fi nanci al di stress. Whi le

such deci si onscould reasonably be left to pri -

vate contracts, a formal bankruptcy law may be

desi rable for other reasons. I f thi slaw de facto

encouragesAPR vi olati ons, i t i sclear that i t

should also i nclude an opt-out provi si on that

allowspri vate agentsto determi ne whether i ts

structure wi ll be benefi ci al to them. Thi si snot

allowed under current U.S. bankruptcy law.

I n such a world, we mi ght expect owner-

operatorsof small fi rmsto i nclude APR vi ola-

ti onsi n thei r contracts, si nce these fi rmsare the

most li kely to lose value from transferri ng thei r

capi tal assets. I n contrast, the value of large,

publi cly traded compani esi slessli kely to be

affected by thei r ownershi p, and we would

therefore expect such compani esto avoi d APR

vi olati onsof any type, aswould fi rmsof any

si ze whose profi t streamsare easi ly affected by

manageri al effort.

Appendix

In thi sappendi x, we prove some of the more

techni cal resultsrequi red i n the text. The fi rst i s

the fact that, i n the model wi th costly bank-

ruptcy,

x* i si ncreasi ng i n . Totally di fferenti at-

i ng ( 4) showsthat

( 15)

d

d

x

.

The numerator of thi sexpressi on i sclearly pos-

i ti ve, asi sthe denomi nator whenever

( 16)

1

c

<

.

Longhofer ( 1995) showsthat whenever thi s

condi ti on doesnot hold, no lendi ng occursi n

equi li bri um. That i s, when c or i stoo large,

credi t rati oni ng results.

The second fact we must prove i sthat

de*/d 0 i n the model wi th ri sk shi fti ng.

Solvi ng ( 11) for R*, substi tuti ng i nto ( 10) , and

si mpli fyi ng showsthat e* i sdefi ned by

( 17) e*

2

2 e*1 0 0,

where 0 = I 2xH ( 1 2) xL + xL,

1 = 2 ( 1 2)

2

( xH xL) , and

2 = ( 1 2) .

Although two rootswi ll solve thi sequati on,

di fferenti ati on of ( 13) wi th respect to e* shows

that the larger root wi ll alwaysbe the one cho-

sen i n equi li bri um. Usi ng the quadrati c formula

to solve for e*, i t i sstrai ghtforward to veri fy that

( 18) xL ( 1

2

420)

,

whi ch must be nonposi ti ve whenever a real

soluti on for e* exi sts.

I t i sworth aski ng what happenswhen the

opti mal e*, asgi ven by the quadrati c formula,

i sgreater than one. Thi swould i mply that the

entrepreneur wi ll alwayschoose the good proj-

ect, regardlessof the level of effort ulti mately

requi red. I n thi scase, small APR vi olati onswi ll

have no i mpact on the fi rmsex ante profi t.

Larger vi olati ons, however, wi ll sti ll reduce the

chance that the entrepreneur wi ll choose the

good project.

de*

d

1 F ( x*)

f ( x*)

x *[1 F( x*) ]

x

x

*

xf(x) dx

( 1 ) [1 F( x*) ] cf( x*)

29

References

Bebchuk, L.A. The Effectsof Chapter 11 and

Debt Renegoti ati on on Ex Ante Corporate

Deci si ons, Harvard Law School Program i n

Law and Economi csDi scussi on Paper

No. 104, December 1991.

Berkovitch, E., and R. Israel. The Bankruptcy

Deci si on and Debt Contract Renegoti ati ons,

Uni versi ty of Mi chi gan, School of Busi ness

Admi ni strati on, unpubli shed manuscri pt,

August 1991.

Betker, B.L. ManagementsI ncenti ves, Equi tys

Bargai ni ng Power, and Devi ati onsfrom Ab-

solute Pri ori ty i n Chapter 11 Bankruptci es,

Journal of Business, vol. 68, no. 2 ( Apri l

1995) , pp. 16183.

Bulow, J.I., and J.B. Shoven. The Bankruptcy

Deci si on, Bell Journal of Economics, vol. 9,

no. 2 ( Autumn 1978) , pp. 43756.

Eberhart,A.C.,W.T. Moore, and R.L. Roenfeldt.

Securi ty Pri ci ng and Devi ati onsfrom the

Absolute Pri ori ty Rule i n Bankruptcy Pro-

ceedi ngs, Journal of Finance, vol. 45, no. 5

( December 1990) , pp. 145769.

Fenning, L.H. The Future of Chapter 11: O ne

Vi ew from the Bench, i n 19931994

Annual Survey of Bankruptcy Law.

Rochester, N.Y.: Clark Boardman Callaghan,

1993, pp. 11327.

Flynn, E. Stati sti cal Analysi sof Chapter 11,

Stati sti cal Analysi sand ReportsDi vi si on of

the Admi ni strati ve O ffi ce of the Uni ted

StatesCourts, unpubli shed manuscri pt,

O ctober 1989.

Franks, J.R., and W.N.Torous. An Empi ri cal

I nvesti gati on of U.S. Fi rmsi n Reorgani za-

ti on, Journal of Finance, vol. 44, no. 3

( July 1989) , pp. 74769.

,and . A Compari son

of Fi nanci al Recontracti ng i n Di stressed

Exchangesand Chapter 11 Reorgani zati ons,

Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 35,

no. 3 ( June 1994) , pp. 34770.

Gale, D., and M. Hellwig. I ncentive-Compatible

Debt Contracts: The O ne-Peri od Problem,

Review of Economic Studies, vol. 52, no. 4

( O ctober 1985) , pp. 64763.

Gertner, R., and D. Scharfstein. A Theory of

Workoutsand the Effectsof Reorgani zati on

Law, Journal of Finance, vol. 46, no. 4

( September 1991) , pp. 1189222.

Harris, M., and A. Raviv. The Desi gn of Bank-

ruptcy Procedures, Northwestern Uni versi ty,

K ellogg Graduate School of Management,

Worki ng Paper No. 137, March 1993.

Innes, R.D. Li mi ted Li abi li ty and I ncenti ve

Contracti ng wi th Ex-ante Acti on Choi ces,

Journal of Economic Theory, vol. 52, no. 1

( O ctober 1990) , pp. 4567.

Jackson,T.H. The Logic and Limits of Bank-

ruptcy Law. Cambri dge, Mass.: Harvard

Uni versi ty Press, 1986.

Longhofer, S.D. A Note on Absolute Pri ori ty

Rule Vi olati ons, Credi t Rati oni ng, and Effi -

ci ency, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland,

Worki ng Paper No. 9513, November 1995.

LoPucki, L.M. The Debtor i n Full Control: Sys-

temsFai lure under Chapter 11 of the Bank-

ruptcy Code?Second I nstallment, American

Bankruptcy Law Journal, vol. 57, no. 3

( Summer 1983) , pp. 24773.

,and W.C.Whitford. Bargai ni ng

over Equi tysShare i n the Bankruptcy Reor-

gani zati on of Large, Publi cly Held Compa-

ni es, University of Pennsylvania Law

Review, vol. 139 ( 1990) , pp. 12596.

Tashjian, E., R.C. Lease, and J.J. McConnell.

Prepacks: An Empi ri cal Analysi sof Prepack-

aged Bankruptci es, Journal of Financial

Economics, vol. 40, no. 1 ( January 1996) ,

pp. 13562.

Townsend, R.M. O pti mal Contractsand Com-

peti ti ve Marketswi th Costly State Veri fi ca-

ti on, Journal of Economic Theory, vol. 21,

no. 2 ( O ctober 1979) , pp. 26593.

30

Weiss, L.A. Bankruptcy Resoluti on: Di rect

Costsand Vi olati on of Pri ori ty of Clai ms,

Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 27,

no. 2 ( O ctober 1990) , pp. 285314.

White, M. J. Publi c Poli cy toward Bankruptcy:

Me-Fi rst and O ther Pri ori ty Rules, Bell Jour-

nal of Economics, vol. 11, no. 2 ( Autumn

1980) , pp. 55064.

. Bankruptcy Costsand the New

Bankruptcy Code, Journal of Finance,

vol. 38, no. 2 ( May 1983) , pp. 47788.

Williamson, S.D. Costly Moni tori ng, Fi nanci al

I ntermedi ati on, and Equi li bri um Credi t

Rati oni ng, Journal of Monetary Economics,

vol. 18, no. 2 ( September 1986) , pp. 15979.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Cross-Border Insolvency Problems - Is The UNCITRAL Model Law The Answer PDFDocument27 pagesCross-Border Insolvency Problems - Is The UNCITRAL Model Law The Answer PDFvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Extremely Entertaining Short Stories PDFDocument27 pagesExtremely Entertaining Short Stories PDFvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Declassified UK Files On Srebrenica - PREM-19-5487 - 2Document100 pagesDeclassified UK Files On Srebrenica - PREM-19-5487 - 2vidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Floppy Infant SyndromeDocument5 pagesFloppy Infant Syndromevidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Declassified UK Paper On Srebrenica - PREM-19-5487 - 1Document110 pagesDeclassified UK Paper On Srebrenica - PREM-19-5487 - 1vidovdan9852No ratings yet

- 275 Export DeclarationDocument3 pages275 Export Declarationvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Russia vs. Ukraine Eurobond - Final Judgment - Judgement 29.03.2017Document107 pagesRussia vs. Ukraine Eurobond - Final Judgment - Judgement 29.03.2017vidovdan9852100% (1)

- Benign Congenital HypotoniaDocument4 pagesBenign Congenital Hypotoniavidovdan9852No ratings yet

- JFK50 ShortlinksDocument7 pagesJFK50 Shortlinksvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- List of 616 English Irregular VerbsDocument21 pagesList of 616 English Irregular Verbsمحمد طه المقطري67% (3)

- Article IV Montenego 2017Document92 pagesArticle IV Montenego 2017vidovdan9852No ratings yet

- A Unified Model of Early Word Learning - Integrating Statistical and Social CuesDocument8 pagesA Unified Model of Early Word Learning - Integrating Statistical and Social Cuesvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Floppy Infant SyndromeDocument5 pagesFloppy Infant Syndromevidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Example Mutual Non Disclosure AgreementDocument2 pagesExample Mutual Non Disclosure Agreementvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Global Dollar Credit and Carry Trades - A Firm-Level AnalysisDocument53 pagesGlobal Dollar Credit and Carry Trades - A Firm-Level Analysisvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- From Privilege To Right - Limited LiabilityDocument22 pagesFrom Privilege To Right - Limited Liabilitymarcelo4lauarNo ratings yet

- A Convenient Untruth - Fact and Fantasy in The Doctrine of Odious DebtsDocument45 pagesA Convenient Untruth - Fact and Fantasy in The Doctrine of Odious Debtsvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- How Children Learn WordsDocument6 pagesHow Children Learn Wordsvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Balancing The Public Interest - Applying The Public Interest Test To Exemption in The UK Freedom of Information Act 2000Document62 pagesBalancing The Public Interest - Applying The Public Interest Test To Exemption in The UK Freedom of Information Act 2000vidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Chapter 11 at TwilightDocument30 pagesChapter 11 at Twilightvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Artigo Previsão de Falência Com Lógica Fuzzy Bancos TurcosDocument13 pagesArtigo Previsão de Falência Com Lógica Fuzzy Bancos TurcosAndrew Drummond-MurrayNo ratings yet

- A Determination of The Risk of Ruin PDFDocument36 pagesA Determination of The Risk of Ruin PDFvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Hanlon Illegitimate DebtDocument16 pagesHanlon Illegitimate DebtVinícius RitterNo ratings yet

- Leases and InsolvencyDocument32 pagesLeases and Insolvencyvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Assessing The Probability of BankruptcyDocument47 pagesAssessing The Probability of Bankruptcyvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- A Reply To Alan Schwartz's 'A Contract Theory Approach To Business Bankruptcy' PDFDocument26 pagesA Reply To Alan Schwartz's 'A Contract Theory Approach To Business Bankruptcy' PDFvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- After The Housing Crisis - Second Liens and Contractual InefficienciesDocument21 pagesAfter The Housing Crisis - Second Liens and Contractual Inefficienciesvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- A Convenient Untruth - Fact and Fantasy in The Doctrine of Odious DebtsDocument45 pagesA Convenient Untruth - Fact and Fantasy in The Doctrine of Odious Debtsvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Too Many To Fail - The Effect of Regulatory Forbearance On Market DisciplineDocument38 pagesToo Many To Fail - The Effect of Regulatory Forbearance On Market Disciplinevidovdan9852No ratings yet

- (ISDA, Altman) Analyzing and Explaining Default Recovery RatesDocument97 pages(ISDA, Altman) Analyzing and Explaining Default Recovery Rates00aaNo ratings yet