Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Surgical Incisions-Their Anatomical Basis Part IV - Abdomen

Surgical Incisions-Their Anatomical Basis Part IV - Abdomen

Uploaded by

pcardosodacosta0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views9 pagesOriginal Title

Surgical Incisions—Their Anatomical Basis Part IV - Abdomen

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views9 pagesSurgical Incisions-Their Anatomical Basis Part IV - Abdomen

Surgical Incisions-Their Anatomical Basis Part IV - Abdomen

Uploaded by

pcardosodacostaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

170

J. Anat. Soc. India 50(2) 170-178 (2001)

J Anat. Soc. India 50(2) 170-178 (2001)

Surgical IncisionsTheir Anatomical Basis

Part IV-Abdomen

*Patnaik, V.V.G.; **Singla, Rajan K.; ***Bansal V.K..

Department of Anatomy, Government Medical College, *Patiala, **Amritsar, ***Department of Surgery, Govt. Medical College &

Hospital, Chandigarh, INDIA.

Abstract. The present paper is a continuation of the previous ones by Patnaik et al 2000 a, b & 2001. Here the anatomical basis of

the various incisions used in anterior abdominal wall their advantages & disadvantages are discussed. An attempt has been made to add

the latest modifications in a concised manner.

Key words : Surgical Incisions, Abdomen, Midline, Paramedian, McBurney, Gridison, Kocher.

Introduction :

It is probably no exaggeration to state that, in

abdominal surgery, wisely chosen incisions and

correct methods of making and closing such wounds

are factors of great importance (Nygaard and

Squatrito, 1996). Any mistake, such as a badly

placed incision, inept methods of suturing, or ill-

judged selection of suture material, may result in

serious complications such as haematoma

formation, an ugly scar, an incisional hernia, or,

worst of all, complete disruption of the wound

(Pollock, 1981; Carlson et al, 1995).

Before the advent of minimally invasive

techniques, optimal access could only be achieved

at the expense of large high morbidity incisions.

Endoscopic and laparoscopic technology has,

however revolutionized these concepts facilitating

patient friendly access to even the most remote of

abdominal organs (Maclntyre, 1994).

It should be the aim of the surgeon to employ

the type of incision considered to be the most

suitable for that particular operation to be

performed. In doing so, three essentials should be

achieved (Zinner et al, 1997):

1. Accessibility

2. Extensibility

3. Security

The incision must not only give ready and

direct access to the anatomy to be investigated but

also provide sufficient room for the operation to be

performed (Velanovich, 1989). The incision should

be extensible in a direction that will allow for any

probable enlargement of the scope of the operation,

but it should interfere as little as possible with the

functions of the abdominal wall. The surgical

incision and the resultant wound represent a major

part of the morbidity of the abdominal surgery.

Planning of an abdominal incision :

In the planning of an abdominal incision,

Nyhus & Baker (1992) stressed that the following

factors must be taken into consideration (a) pre-

operative diagnosis (b) the speed with which the

operation needs to be performed, as in trauma or

major haemorrhage, (c) the habitus of the patient,

(d) previous abdominal operation, (e) potential

placements of stomas (Funt, 1981; Telfer et al,

1993). Ideally, the incision should be made in the

direction of the lines of cleavage in the skin so that

a hairline scar is produced.

The incision must be tailored to the patients

need but is strongly influenced by the surgeons

preference. In general, re-entry into the abdominal

cavity is best done through the previous laparotomy

incision. This minimizes further loss of tensile

strength of the abdominal wall by avoiding the

creation of additional fascial defects (Fry & Osler,

1991).

Care must be taken to avoid tramline or

acute angle incisions (Figure 1), which could lead

to devascularisation of tissues. It is also helpful if

incisions are kept as far as possible from

established or proposed stoma sites and these

171

J. Anat. Soc. India 50(2) 170-178 (2001)

Classification of incisions :

The incisions used for exploring the abdominal

cavity can be classified as :

(A) Vertical incision : These may be

(i) Midline incision

(ii) Paramedian incisions

(B) Transverse and oblique incisions :

(i) Kocher's subcostal Incision

(a) Chevron (Roof top

Modification)

(b) Mercedes Benz Modification

(ii) Transverse Muscle dividing incision

(iii) Mc Burneys Grid iron or muscle

spliting incision

(iv) Oblique Muscle cutting incision

(v) Pfannenstiel incision

(vi) Maylard Transverse Muscle cutting

Incision

(C) Abdominothoracic incisions

A. Vertical incisions :

Vertical incisions include the midline incision,

paramedian incision, and the Mayo-Robson

extension of the paramedian incision.

(i) Midline Incision (Figure 2) :

Almost all operations in the abdomen and

retroperitoneum can be performed through this

universally acceptable incision (Guillou et al, 1980).

Advantages (a) It is almost bloodless, (b) no muscle

fibres are divided, (c) no nerves are injured, (d) it

affords goods access to the upper abdominal

viscera, (e) It is very quick to make as well as to

close; it is unsurpassed when speed is essential

(Clarke, 1989) (f) a midline epigastric incision also

can be extended the full length of the abdomen

curving around the umbilical scar (Denehy et al,

(1998).

In the upper abdomen, the incision is made in

the midline extending from the area of xiphoid and

ending immediately above the umbilicus (Ellis,

1984). Skin, fat, linea alba and peritoneum are

divided in that order. Division of the peritoneum is

best performed at the lower end of the incision, just

above the umbilicus so that falciform ligament can

(a) (b)

Fig. 1. (a) Tramline Incision. (b) Acute angle incision.

stomas should be marked preoperatively with skin

marking pencils to avoid any mistakes (Burnand &

Young, 1992).

Cosmetic end results of any incision in the

body are most important from patients point of view.

Consideration should be given wherever possible, to

siting the incisions in natural skin creases or along

Langers lines. Good cosmesis helps patient morale.

Much of the decision about the direction of the

incision depends on the shape of the abdominal

wall. A short, stocky person sometimes has a longer

incision and frequently better exposure, if the

incision is transverse. A tall, thin, asthenic patient

has a short incision if it is made transversally,

whereas a vertical incision affords optimal exposure

(Greenall et al, 1980).

Certain operations are ideally done through a

transverse or subcostal incision, for example

cholecystectomy through a right Kochers incision,

right hemicolectomy through an infraumbilical

transverse incision, and splenectomy through a left

subcostal incision. Vagotomy and antrectomy can be

done through a bilateral subcostal incision with a

longer right and shorter left extension if the patient

is stocky or obese (Grantcharov & Rosenberg,

2001).

Certain incisions, popular in the past, have

been abandoned, and appropriately so. One

example of this is the para-rectus incision made at

the lateral border of the rectus sheath. This incision

was used until the mid 1940 primarily for the

removal of the gall bladder, the spleen, and the left

colon. It denervates the rectus muscle and produces

an ideal environment for the development of

postoperative ventral hernia, and has absolutely

nothing to recommend it (Nyhus & Baker, 1992).

Patnaik, V.V.G., et al

172

J. Anat. Soc. India 50(2) 170-178 (2001)

be seen and avoided. If necessary for exposure, the

ligament can be divided between clamps and

ligated. A few centimeters of upwards extension can

be gained by extending the incision to either side of

the xiphoid process, or actually excising the xiphoid

(Didolkar & Vickers, 1995). The extraperitoneal fat is

abundant and vascular in this area, and small

vessels here need to be coagulated with diathermy.

The infraumbilical midline incision also divides

the linea alba. Because the linea alba is

anatomically narrow at the inferior portion of the

abdominal wall, the rectus sheath may be opened

unintentionally, although this is of no consequence.

In the lower abdomen, the peritoneum should be

opened in the uppermost area to avoid possible

injury to the bladder.

It is a good practice to place a bladder catheter

before any surgery on the lower abdomen and to

curve the properitoneal and peritoneal incisions

laterally when approaching the pubic symphysis to

avoid entry into the bladder (Nyhus & Baker, 1992).

Special care is needed when operating on

patients with intestinal obstruction or when re-

exploring following previous abdominal surgery (Fry

& Osler, 1991). In intestinal obstruction, distended

bowel loops may be there immediately below the

incision and in re-exploration, the bowel may be

adherent to the peritoneum. The way to avoid this is

to open the peritoneum in a virgin area at the upper

or lower part of the incision (Levrant et al, 1994).

(ii) Paramedian Incision (Figure 3)

The paramedian incision has two theoretical

advantages. The first is that it offsets the vertical

incision to the right or left, providing access to the

lateral structures such as the spleen or the kidney.

The second advantage is that closure is theoretically

more secure because the rectus muscle can act as

a buttress between the reapproximated posterior

and anterior fascial planes (Cox et al, 1986).

Fig. 2. Midline Incision

Fig. 3. Paramedian Incisions

The skin incision is placed 2 to 5 cm lateral to

the midline over the medial aspect of the bulging

transverse convexity of the rectus muscle. Extra

access can be obtained by sloping the upper

extremity of the incision upwards to the xiphoid

(Didolkar et al, 1995).

Skin and subcutaneous fat are divided along

the length of the wound. The anterior rectus sheath

is exposed and incised, and its medial edge is

grasped and lifted up with haemostats. The medial

portion of the rectus sheath then is dissected from

the rectus muscle, to which the anterior sheath

adheres. Segmental blood vessels encountered

during the dissection should be coagulated. Once

the rectus muscle is free of the anterior sheath it

can be retracted laterally because the posterior

sheath is not adherent to the rectus muscle. The

posterior sheath and the peritoneum which are

adherent to each other, are excised vertically in the

same plane as the anterior fascial plane (Brennan et

al, 1987). The deep inferior epigastric vessels are

encountered below the umbilicus and require

ligation and division if they course medially along

the line of the incision (Chuter et al, 1992).

A paramedian incision below the umbilicus is

made in a similar manner. The only difference is

that inferior epigastric vessels are exposed in the

posterior compartment of the rectus sheath and the

transversalis fascia is found in the anterior fascial

Surgical Incisions-Abdomen

173

J. Anat. Soc. India 50(2) 170-178 (2001)

layer below the semicircular line of Douglas.

some surgeons still prefer to split the rectus

muscle rather than dissect it free (Guillou et al,

1980). In this rectus-splitting technique, the muscle

is split longitudinally near its medial border (medial

1/3rd or preferably one-sixth), after which posterior

layer of the rectus sheath and peritoneum are

opened in the same line. This incision can be made

and closed quickly and is particularly valuable in

reopening the scar of a previous paramedian

incision. In such circumstances, it is very difficult, or

indeed impossible to dissect the rectus muscle away

from the rectus sheath.

Disadvantages :

1. It tends to weaken and strip off the

muscles from its lateral vascular and

nerve supply resulting in atrophy of the

muscle medial to the incision.

2. The incision is laborius and difficult to

extend superiorly as is limited by costal

margin.

3. It doesnt give good access to

contralateral structures.

The Mayo-Robson extension of the

paramedian incision is accomplished by curving the

skin incision towards the xiphoid process. Incision of

the fascial planes is continued in the same direction

to obtain a larger fascial opening (Pollock, 1981).

(B) Transverse Incisions (Figure 4)

Transverse incisions include the Kocher

subcostal incision, transverse muscle dividing,

McBurney, Pfannenstiel, and Maylard incisions.

(i) Kocher subcostal incision (Figure 5)

Theodore Kocher originally described the

subcostal incision; it affords excellent exposure to

the gall bladder and biliary tract and can be made

on the left side to afford access to the spleen

(Kocher, 1903). It is of particular value in obese and

muscular patients and has considerable merit if

diagnosis is known and surgery planned in advance.

Fig. 4. Transverse and transverse-oblique

Incisions. A. Kocher incision. B. Transverse

Incision. C. Rockey-Davis incision. D. Maylard

incision. E. Pfannenstiel incision

Fig. 5. Kochers Incision

The subcostal incision is started at the midline,

2 to 5 cm below the xiphoid and extends

downwards, outwards and parallel to and about 2.5

cm below the costal margin (Hardy 1993; Dorfman

et al, 1997). Extension across the midline and down

the other costal margin may be used to provide

generous exposure of the upper abdominal viscera.

The rectus sheath is incised in the same direction as

the skin incision, and the rectus muscle is divided

with cautery; the internal oblique and transversus

abdominis muscles are divided with cautery. Some

authors have described the retraction of rectus

muscle instead of dividing it (Brodie et al, 1976; Fink

& Budd, 1984).

Special attention is needed for control of the

branches of the superior epigastric vessels, which

lie posterior to and under the lateral portion of the

rectus muscle. The small eighth thoracic nerve will

almost invariably be divided; the large ninth nerve

must be seen and preserved to prevent weakening

of the abdominal musculature. The incision is

deepened to open the peritoneum (Dorfman et al,

1997).

In the recent years, many surgeons have

advocated the use of a small 5-10 cm incision in the

subcostal area for cholecystectomy - mini-lap

Patnaik, V.V.G., et al

174

J. Anat. Soc. India 50(2) 170-178 (2001)

because the incision passes between adjacent

nerves without injuring them. The rectus muscle has

a segmental nerve supply, so there is no risk of a

transverse incision depriving the distal part of the

rectus muscle of its innervation. Healing of the scar,

in effect, simply results in the formation of a man

made additional fibrous intersection in the muscle

(Pemberton and Manaz, 1971).

(ii) Transverse Muscle-dividing incision (Figure 6)

The operative technique used to make such an

incision is similar to that for the Kocher incision. In

newborns and infants, this incision is preferred,

because more abdominal exposure is gained per

length of the incision than with vertical exposure

because the infants abdomen has a longer

transverse than vertical girth (Gauderer, 1981). This

is also true of short, obese adults, in whom

transverse incision often affords a better exposure.

(iii) McBurney Grid iron or Muscle-split incision

(Figure 7)

The McBurney incision, first described in 1894

by Charles McBurney is the incision of choice for

most appendicectomies (McBurney, 1894). The

level and the length of the incision will vary

according to the thickness of the abdominal wall and

the suspected position of the appendix (Jelenko &

Davis 1973; Watts & Perrone, 1997). Good healing

and cosmetic appearance are virtually always

achieved with a negligible risk of wound disruption

or herniation.

cholecystectomy (Seenu & Misra, 1994). This

incision is similar to the Kochers incision except for

the length of the incision. The major advantages of

this incision are lesser postoperative pain, early

recovery from the surgery and return to work and

good cosmetic results (Coelho et al, 1993). But

diadvantage is less exposure, which can be

dangerous in cases of difficult anatomy or lot of

adhesions and chances of injury to bile ducts or

other structures (Kopelman et al, 1994; Gupta et al,

1994).

(a) Chevron (Roof Top) Modification :

The incision may be continued across the

midline into a double Kocher incision or roof top

approach (Chevron Incision) (Figure 6), which

provides excellent access to the upper abdomen

particularly in those with a broad costal margin

(Chute et al, 1968; Brooks et al, 1999). This is

useful in carrying out total gastrectomy, operations

for renovascular hypertension, total

oesophagectomy, liver transplantation, extensive

hepatic resections, and bilateral adrenalectomy etc

(Chino & Thomas, 1985; Pinson et al, 1995;

Miyazaki et al, 2001).

Fig. 6. A.. A: Rooftop incision; B..: Mercedes Benz extension

(b) The Mercedes Benz Modification :(Fig. 6)

Variant of this incision consists of bilateral low

Kochers incision with an upper midline limb up to

and through the xiphisternum (Sato et al, 2000).

This gives excellent access to the upper abdominal

viscera and, in particular to all the diaphragmatic

hiatuses (Yoshinaga, 1969; Motsay et al, 1973;

Brooks et al, 1999).

The rectus muscle can be divided transversely.

Its anterior and posterior sheaths are closed without

any serious weakening of the abdominal muscle

Classically, the McBurney incision is made at

the junction of the middle third and outer thirds of a

Fig. 7. Surface markings of the right iliac fossa

appendicectomy incision. A. The Classic McBurney incision

is obnliquely placed. B. Most surgeons today use a more

transverse skin-crease incision

Surgical Incisions-Abdomen

175

J. Anat. Soc. India 50(2) 170-178 (2001)

line running from the umbilicus to the anterior

superior iliac spine, the McBurney point (Watts,

1991). However, if palpation reveals a mass, the

incision can be placed directly over the mass.

McBurney originally placed the incision obliquely,

from above laterally to below medially. However, the

skin incision can be placed in a skin crease

transversely [Rockey-Davis Incision (Fig 4c) or Lanz

Incision or Bikini Incision], which provides a better

cosmetic result (Delany & Carnevale, 1976;

Pleterski & Temple, 1990). Otherwise, the two

incisions are similar.

If it is anticipated that it may be necessary to

extend the incision, then the incision should be

placed obliquely, which enables it to be extended

laterally as a muscle splitting incision (Losanoff &

Kjossev, 1999).

After the skin and subcutaneous tissue are

divided, the external oblique aponeurosis is divided

in the direction of its fibres; exposing the underlying

internal oblique muscle. A small incision is then

made in this muscle adjacent to the outer border of

the rectus sheath. The opening is enlarged to permit

introduction of two index fingers between the muscle

fibres so that internal oblique and transversus can

be retracted with a minimal amount of damage. The

peritoneum is then grasped with a thumb forceps,

elevated and opened.

If further access is required, the wound can be

easily enlarged by dividing the anterior sheath of the

rectus muscle in line with the incision, after which

rectus muscle is retracted medially (Jelenko &

Davis, 1973; Moneer, 1998). Wide lateral extension

of the incision can be affected by combination of

division and splitting of the oblique muscles along

the line of their fibres in the lateral direction (Weir

extension) (Askew, 1975).

This incision also may be used in the left lower

quadrant to deal with certain lesions of the sigmoid

colon, such as drainage of a diverticular abscess.

The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves

cross the incision for appendectomy and their

accidental injury should be prevented which can

predispose the patient to inguinal hernia formation in

the postoperative period (Mandelkow & Loeweneck,

1988).

(iv) Oblique Muscle-cutting incision

This incision bears the eponym of the

Rutherford-Morrison incision (Talwar et al, 1997).

This is extension of the McBurney incision by

division of the oblique fossa and can be used for a

right or left sided colonic resection, caecostomy or

sigmoid colostomy.

(v) Pfannenstiel incision (Figure 4)

The Pfannenstiel incision is used frequently by

gynaecologists and urologists for access to the

pelvis organs, bladder, prostate and for caesarean

section (Ayers & Morley, 1987; Mendez et al, 1999;

Hendrix et al, 2000). The skin incision is usally 12

cm long and is made in a skin fold approximately 5

cm above symphysis pubis. The incision is

deepened through fat and superficial fascia to

expose both anterior rectus sheaths, which are

divided along the entire length of the incision. The

sheath is then separated widely, above and below

from the underlying rectus muscle. It is necessary to

separate the aponeurosis in an upward direction,

almost to the umbilicus and downwards to the pubis.

The rectus muscles are then retracted laterally and

the peritoneum opened vertically in the midline, with

care being taken not to injure the bladder at the

lower end.

The incision offers excellent cosmetic results

because the scar is almost always hidden by the

patients pubic hair postoperatively (Griffiths, 1976).

Because the exposure is limited this incision should

be used only when surgery is planned on the pelvic

organs (Mendez et al, 1999).

(vi) Maylard Transverse Muscle Cutting Incision

(Figure 4)

Many surgeons prefer this incision because it

gives excellent exposure of the pelvic organs

(Helmkamp & Kreb, 1990; Brand, 1991). The skin

incision is placed above but parallel to the traditional

placement of Pfannenstiel incision. The rectus

fascia and muscle are then cut transversely, and the

incision is continued laterally as far as necessary,

dividing external and internal oblique muscles; the

transverses abdominis and transversalis fascia are

opened in the direction of their fibres.

Patnaik, V.V.G., et al

176

J. Anat. Soc. India 50(2) 170-178 (2001)

(C) Thoracoabdominal Incision (Figures 8 & 9)

The thoracoabdominal incision, either right or

left, converts the pleural and peritoneal cavities into

one common cavity and thereby gives excellent

exposure. Laparotomy incisions, whether upper

midline, upper paramedian or upper oblique can be

easily extended into either the right or left chest for

better exposure (Nyhus & Baker, 1992).

The right incision may be particularly useful in

elective and emergency hepatic resections (Kise et

al, 1997). The left incision may be used effectively

in resection of the lower end of the esophagus and

proximal portion of the stomach (Molina et al, 1982;

Ti, 2000).

When liver resection is anticipated, it is now

more common to give a sternum splitting incision

than to extending it into the right pleural space (Sato

et al, 2000). The reasons for this are that the

sternum heals with considerably less pain than does

the costochondral junction; the exposure is as good,

and the intrapericardial vena cava can be controlled

through this incision if there is untoward venous

bleeding (Miyazaki et al, 2001).

The thoracic incision is carried down through

the subcutaneous fat and the lattismus dorsi,

serratus anterior and external oblique muscles. The

intercostals muscles are divided with cautery and

pleural cavity is opened and lung allowed to

collapse. The incision is continued across the costal

margin, and the cartilage is divided in a V shape

manner with a scalpel so that the two ends

interdigitate and can be closed more securely. A

chest retractor is inserted and opened to produce

wide spreading of the intercostal space. After

ligation of the phrenic vessels in the line of the

incision, the diaphragm is divided radially (Zinner et

al, 1997).

References :

1. Askew, A.R. (1975) : The Fowler-Weir approach to

appendicectomy. British Journal of Surgery, 62(4): 303-4.

2. Ayers, J.W., Morley, G.W. (1987): Surgical incision for

caesarean section. Obstetrics Gynaecology, 70(5): 706-8.

3. Brand, E. (1991): The Cherney incision for gynaecologic

cancer. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology,

165(1): 235.

4. Brennan, T.G., Jones, N.A., Guillou, P.J. (1987): Lateral

paramedian incision. British Journal of Surgery, 74(8): 736-7.

5. Brodie. T.E., Jackson, J.T., McKinnon, W.M. (1976): A

muscle retracting subcostal incision for cholecystectomy.

Surgery Gynaecology Obstetrics 143(3): 452-3.

6. Brooks, M.J., Bradbury, A., Wolfe, H.N. (1999) : Elective

repair of type IV thoraco-abdominal aortic aneurysms;

experience of a subcostal (transabdominal) approach.

European Journal of Vascular Endovascular Surgery, 18(4):

290-3.

7. Burnand, K.G., Young, A.E.: The New Airds Companion in

Surgical Studies. Churchil Livingstone Edinburgh (1992).

8. Carlson, M.A., Ludwig, K.A., Condon, R.E. (1995): Ventral

hernia and other complications of 1,000 midline incisions.

Southern Medical Journal Apr; 88(4): 450-3.

Fig. 9. Surface markings of the thoracoabdominal incision

Fig. 8. Corkscrew position for throaco abdominal incision

The patient is placed in the cork-screw

position. (Fig. 8) The abdomen is tilted about 45

from the horizontal by means of sand bags, and the

thorax twisted into fully lateral position. This position

allows maximal access to both abdomen and the

thoracic cavity (Morrissey & Hollier, 2000). The

abdomen is explored first through the abdominal

incision to assess for the operative exposure and

necessity for thoracic extension. The incision is

extended along the line of the eighth interspace, the

space immediately distal to the inferior pole of the

scapula (Dudley, 1983). (Fig. 9)

Surgical Incisions-Abdomen

177

J. Anat. Soc. India 50(2) 170-178 (2001)

9. Chino, E.S., Thomas, C.G. (1985): An extended Kocher

incision for bilateral adrenalectomy. American Journal of

Surgery, 149(2): 292-4.

10. Chute, R., Baron, J.A. Jr., Olsson, C.A. (1968): The

transverse upper abdominal chevron incision in urological

surgery. Journal of Urology, 99(5): 528-32.

11. Chuter, T.A., Steinberg, B.M., April, E.W. (1992): Bleeding

after extension of the midline epigastric incision. Surgery

Gynaecology Obstetrics, 174(3): 236.

12. Clarke, J.M. (1989): Case for midline incisions. Lancet, Mar

18; 1 (8638): 622.

13. Coelho, J.C., de Araujo, R.P., Marchensini, J.B., Coelho, I.C.,

de Araujo, L.R. (1993): Pulmonary function after

cholecystectomy performed through Kochers incision, a

mini-incision, and laparoscopy. World Journal of Surgery.

17(4): 544-6.

14. Cox, P.J., Ausobsky, J.R., Ellis, H., Pollock, A.V. (1986):

Towards no incisional hernias: lateral paramedian versus

midline incisions. Journal of Royal Society of Medicine, Dec.

79(12): 711-12.

15. Delany, H.M., Carnevale, N.J. (1976): A Bikini incision for

appendicectomy. American Journal of Surgery; 132(1): 126-

27.

16. Denehy, T.R., Einstein, M., Gregori, C.A., Breen, J.L. (1998):

Symmetrical periumbilical extension of a midline incision: a

simple technique. Obstetrics Gynaecology 91(2): 293-94.

17. Didolkar, M.S., Vickers, S.M. (1995): Perixiphoid extension of

the midline incisions. Journal of American College of

Surgery, 180(6): 739-41.

18. Dorfman, S., Rincon, A., Shortt, H. (1997): Cholecystectomy

via Kocher incision without peritoneal closure. Investigation

Clinics, 38(1): 3-7.

19. Dudley, H.: Robe and Smiths Operative Surgery. In:

Alimentary Tract and abdominal wall. Volume 1 General

Principles, 4th edn. Butterworths London: (1983).

20. Ellis, H. (1984): Midline abdominal incisions. British Journal

of Obstetrics and Gynaecology; 91(1): 1-2.

21. Fink, D.L., Budd, D.C. (1984): Rectus muscle preservation in

oblique incisions for cholecystectomy. American Journal of

Surgery. 50(11): 628-36.

22. Fry D.E., Osler, T. (1991): Abdominal wall considerations and

complications in reoperative surgery. Surgery Clinics of North

America, 71(1): 1-11.

23. Funt, M.I. (1981): Abdominal incisions and closures. Clinical

Obstetrics Gynaecology, 24(4): 1175-85.

24. Gauderer, M.W.L. (1981): A rationale for the routine use of

transverse abdominal incision in infants and children. Journal

of Paediatric Surgery 16 (Sup.1): 583.

25. Grantcharov, T.P., Rosenberg, J. (2001): Vertical compared

with transverse incision in abdominal surgery. European

Journal of Surgery: 167(4): 260-7.

26. Greenall, M.J., Evans, M., Pollock, A.V. (1980): Midline or

transverse laparotomy ? A random controlled clinical trial.

Part I: Influence on healing. British Journal of Surgery, 67(3):

188-90.

27. Grriffiths, D.A. (1976): A reappraisal of the Pfannenstiel

incision. British Journal of Urology, 46(6): 469-74.

28. Guillou, P.J., Hall, T.J., Donaldson, D.R., Broughton, A.C.,

Brennan, T.G. (1980): Vertical abdominal incisions - a

choice ? British Journal of Surgery, 67(6): 395-9.

29. Gupta, S., Elanogovan, K., Coshic, O., Chumber, S. (1994):

Minicholecystectomy: can we reduce it further ? Journal of

Surgery Oncology, 56(3): 167.

30. Hardy, K.J. (1993): Carl Langenbuch and the Lazarus

Hospital: events and circumstances surrounding the first

cholecystectomy. Australian Journal of surgery, 63(1): 56-64.

31. Helmkamp, B.F., Krebs, H.B. (1990): The Maylard incision in

gynaecologic surgery. American Journal of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology, 163(5Pt.1): 1554-7.

32. Hendrix, S.L., Schimp, V., Martin, J., Singh, A., Kruger, M.,

McNeelay, S.G. (2000): The legendary superior strength of

the pfannensteil incision: a myth ? American Journal of

Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 182(6) : 1446-51.

33. Jelenko C 3rd., Davis, L.P. (1973): A transverse lower

abdominal appendicectomy incision with minimal muscle

deranagement. Surgery Gynaecology Obstetrics, 136(3):

451-2.

34. Kise, Y., Takayama T., Yamamoto, J., Shimada, K., Kosuge,

T., Yamasaki S., Makuuchi, M. (1997): Comparison between

thoracaobdominal and abdominal approaches in occurrence

of pleural effusion after liver cancer surgery.

Hepatogastroenterology, 44(17): 1397-1400.

35. Kocher, T. Textbook of operative surgery, 2nd ed. Black

London, England: (1903)

36. Kopelman, D., Schein, M., Assalia, A., Meizlin, V.,

Harshmonia, M. (1994): Technical aspects of

minicholecystectomy. Journal of American College of

Surgery. 178(6): 624-5.

37. Levrant, S.G., Bieber, E., Barnes, R. (1994): Risk of anterior

abdominal wall adhesions increases with number and type of

previous laparotomy. Journal of American Association of

Gynaecology Laparotomy, 1 (4, Part 2): 19.

38. Losanoff, J.E., Kjossev, K.T. (1999): Extension of

McBurneys incision: old standards versus new options.

Surgery Today, 26(6): 584-6.

39. Mandelkow, H., Leoweneck, H. (1988): The iliohypogastric

and ilioinguinal nerves. Distribution in the abdominal wall,

danger areas in surgical incisions in the inguinal and pubic

regions and reflected visceral pain in their dermatomes.

Surgery Radiology Anatomy, 10(2): 145-9.

40. Maclntyre,, I.M.C.: Pratical Laparoscopic Surgery for General

Surgeons. Butterworth-Hennemann. Oxford: (1994)

41. McBurney, C. (1894): The incision made in the abdominal

wall in cases of appendicitis, with a description of a new

method of operating. Annals of Surgery, 20: 38.

42. Mendez, L.E., Cantuaria, G., Angioli, R., Mirhashemi, R.,

Gabriel, C., Estape, R., Penalver, M. (1999): Evaluation of the

Pfannensteil incision for radical abdominal hysterectomy with

pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. International

Journal of Gynaecology Cancer, 9(5): 418-20.

43. Miyazaki, K., Ito, H., Nakagawa, K., Shimizu, H., Yoshidome,

H., Shimizu, Y., Ohtsuka, M., Togawa, A., Kimura, F. (2001):

An approach to intrapericardial inferior vena cava through the

abdominal cavity, without median sternotomy, for total hepatic

vascular exclusion. Hepatogastroenterology, 48(41): 1443-6.

44. Molina, J.E., Lawton, B.R., Myers, W.O., Humphrey, E.W.

(1982): Esophagogastrectomy for adenocarcinoma of the

cardia. Ten years experience and current approach. Annals

of Surgery, 195(2): 146-51.

45. Moneer, M.M. (1998): Avoiding muscle cutting while

extending McBurneys incision: a new surgical concept.

Surgery Today, 28(2): 235-9.

46. Morrissey, N.J., Hollier, L.H. (2000): Anatomic exposures in

thoracoabdominal aortic surgery. Semin Vascular Surgery,

13(4): 283-9.

Patnaik, V.V.G., et al

178

J. Anat. Soc. India 50(2) 170-178 (2001)

47. Motsay, G.J., Alho, A., Lillehei, R.C. (1973): Diastolic

hypertension corrected by operation: a review. Journal of

Surgical Research, 15(6): 433-49.

48. Nygaard, I.E., Squatrito, R.C. (1996): Abdominal incisions

from creation to closure. Obstetrics Gynaecology Surgery

51(7): 429-36.

49. Nyhus, L.M. & Baker, R.J. : Mastery of Surgery In :

Abdominal Wall Incisions. 2nd Edn Little Brown & Co.

Boston. : 444-452 (1992).

50. Patnaik, V.V.G., Singla, R.K., Bala Sanju (2000a): Surgical

Incisions-Their anatomical basis. Part-I Head & Neck.

Journal of The Anatomical Society of India 49(1): pp 69-77.

51. Patnaik, V.V.G., Singla, R.K., Gupta, P.N. (2000b): Surgical

Incisions-Their anatomical basis. Part-II Upper limb. Journal

of The Anatomical Society of India 49(2): pp 182-190.

52. Patnaik, V.V.G., Singla, R.K., Gupta, P.N. (2001): Surgical

Incisions-Their anatomical basis. Part-III Lower limb. Journal

of The Anatomical Society of India 50(1): pp 48-58.

53. Pemberton, L.B., Manaz, W.G. (1971): Complications after

vertical and transverse incisions for cholecystectomy.

Surgery Gynaecology Obstetrics, 132(5): 892-4.

54. Pinson, C.W., Drougas, J.G., Lalikos, J.L. (1995): Optimal

exposure for hepatobiliary operations using the Bookwalter

self-retaining retractor. American Journal of Surgery, 61(2):

178-81.

55. Pleterski, M., Temple, W.J. (1990): Bikini appendicectomy

incision as an alternative to the McBurney approach for

appendicitis. Canadian Journal of Surgery, 33(5): 343-5.

56. Pollock, A.V. (1981): Laparotomy. Journal of Social Medicine

74(7): 480-4.

57. Sato, H., Sugawara, Y., Yamasaki, S., Shimada, K.,

Takayama, T., Makuuchi, M., Kosuge, T. (2000):

Thoracoabdominal approaches versus inverted T incision for

posterior sgementectomy in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Hepatogastroenterology, 47(32): 504-6.

58. Seenu, V., Misra, M.C. (1994): Mini-lap cholecystectomy - an

attractive alternative to conventional cholecystectomy.

Tropical Gastroenterology, 15(1): 29-31.

59. Talwar, S., Laddha, B.L., Jain, S., Prasad, P. (1997): Choice

of incision in surgical management of small bowel

perforations in enteric fever. Tropical Gastroenterology, 18(2):

78-9.

60. Telfer, J.R., Canning, G., Galloway, D.J. (1993): Comparative

study of abdominal incision techniques. British Journal of

Surgery, Feb; 80(2): 233-5.

61. Ti, T.K. (2000): Surgical approach and results of surgery in

adenocarcinoma of the gastro-oesophageal junction.

Singapore Medical Journal, 41(1): 14-8.

62. Velanovich, V. (1989): Abdominal incision, Lancet, 4;1(8636):

508-9.

63. Watts. G.T. (1991): McBurneys point-factor or fiction. Annals

of Royal College of Surgery England, 73(3): 199-200).

64. Watts, G.T., Perone, N. (1997): Appendicectomy. Southern

Medical Journal, 90(2): 263.

65. Yoshinaga, K. (1969): Operable hypertensions. Japanese

Circ Journal, 33(12): 1627-8.

66. Zinner, M.J., Schwartz, S.I., Ellis, H. Maingots abdominal

operations In: Incisions, closures and management of the

wound. Ellis, H. (Edr), 10th Edn. Prentice Hall International

Inc. N. Jersey, pp. 395-426. (1997).

Surgical Incisions-Abdomen

You might also like

- Reconstruction of Defects of The Posterior Pinna.15Document4 pagesReconstruction of Defects of The Posterior Pinna.15cliffwinskyNo ratings yet

- Semilunar Coronally Repositioned FlapDocument5 pagesSemilunar Coronally Repositioned FlapTarun Kumar Bhatnagar100% (1)

- Basic Brain Anatomy and Physiology PDFDocument10 pagesBasic Brain Anatomy and Physiology PDFSenthilkumar Thiyagarajan100% (3)

- McKenzie Self-Treatments For SciaticaDocument3 pagesMcKenzie Self-Treatments For SciaticaSenthilkumar Thiyagarajan80% (5)

- Orthopedic Assessment For PhysiotherapistDocument3 pagesOrthopedic Assessment For Physiotherapistsenthilkumar76% (21)

- Varaha KavachamDocument10 pagesVaraha KavachamMukunda VenugopalNo ratings yet

- Surgical IncisionsDocument35 pagesSurgical IncisionsRoselle Angela Valdoz MamuyacNo ratings yet

- Surgical Incisions AbdomenDocument9 pagesSurgical Incisions Abdomensnapb202No ratings yet

- Sites of IncisionDocument11 pagesSites of IncisionMi LaNo ratings yet

- Me and DR KhalidDocument29 pagesMe and DR KhalidUmer KhanNo ratings yet

- Surgical Incisions: STJ - Dr. Aylin Mert 0902110019Document22 pagesSurgical Incisions: STJ - Dr. Aylin Mert 0902110019NiyaNo ratings yet

- Incision SitesDocument4 pagesIncision SitesmidskiescreamzNo ratings yet

- Classification of IncisionsDocument7 pagesClassification of IncisionsEleazar MagsinoNo ratings yet

- Tibial Pilon Fractures - OrIF and or External FixationDocument9 pagesTibial Pilon Fractures - OrIF and or External FixationsteoeviciNo ratings yet

- The Keystone Design Perforator Island Flap in Reconstructive SurgeryDocument9 pagesThe Keystone Design Perforator Island Flap in Reconstructive SurgeryCristina Iulia100% (1)

- Surgicalincisions 150519180458 Lva1 App6892 PDFDocument22 pagesSurgicalincisions 150519180458 Lva1 App6892 PDFAbdul Qadir KhurramNo ratings yet

- Print Test Page556Document5 pagesPrint Test Page556andhikaaji4980No ratings yet

- UELI EGLI, WERNER H. VOLLMER AND KLAUS H. RATEITSCHAK. Follow-Up Studies of Free Gingival GraftsDocument8 pagesUELI EGLI, WERNER H. VOLLMER AND KLAUS H. RATEITSCHAK. Follow-Up Studies of Free Gingival GraftsSebastián BernalNo ratings yet

- Tibial Fractures Useful Plastering Technique: MethodDocument4 pagesTibial Fractures Useful Plastering Technique: MethodgregraynerNo ratings yet

- Kugel Repair For HerniasDocument21 pagesKugel Repair For HerniasElias Emmanuel JaimeNo ratings yet

- Articol RamirezDocument6 pagesArticol RamirezDragoș PopaNo ratings yet

- Skin IncisionsDocument1 pageSkin IncisionsShanna Marie MelodiaNo ratings yet

- Review Article: A History of Endoscopic Lumbar Spine Surgery: What Have We Learnt?Document9 pagesReview Article: A History of Endoscopic Lumbar Spine Surgery: What Have We Learnt?cogajoNo ratings yet

- Interstitial Incisional Hernia Following Appendectomy: Case ReportDocument2 pagesInterstitial Incisional Hernia Following Appendectomy: Case ReportSCJUBv Chirurgie INo ratings yet

- Jurnal OrthopediDocument9 pagesJurnal OrthopediRetti TriNo ratings yet

- Scitemed Imj 2017 00036-1Document4 pagesScitemed Imj 2017 00036-1bernicemerryNo ratings yet

- TECNICADocument7 pagesTECNICASiris Rieder GarridoNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Abdominal Incisions in General Surgery: A ReviewDocument5 pagesReview Article: Abdominal Incisions in General Surgery: A ReviewMoxa ShahNo ratings yet

- Generations of The Plug-and-Patch Repair: Its Development and Lessons From HistoryDocument1 pageGenerations of The Plug-and-Patch Repair: Its Development and Lessons From HistorycesaliapNo ratings yet

- Insisi LukaDocument48 pagesInsisi LukaRiska RiantiNo ratings yet

- Hernia Repair 3Document38 pagesHernia Repair 3caliptra36No ratings yet

- Rosenbrg-Goss2020 Article AModifiedTechniqueOfTemporomanDocument10 pagesRosenbrg-Goss2020 Article AModifiedTechniqueOfTemporomanMarcela RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Keystone Flap: Kyle S. Ettinger, MD, DDS, Rui P. Fernandes, MD, DMD, FRCS (Ed), Kevin Arce, MD, DMDDocument14 pagesKeystone Flap: Kyle S. Ettinger, MD, DDS, Rui P. Fernandes, MD, DMD, FRCS (Ed), Kevin Arce, MD, DMDlaljadeff12No ratings yet

- Marinelli - Surgical Approaches - 2014Document9 pagesMarinelli - Surgical Approaches - 2014Giulio PriftiNo ratings yet

- Pedicled Fasciocutaneous and Adipofascial FlapsDocument16 pagesPedicled Fasciocutaneous and Adipofascial FlapspuchioNo ratings yet

- Notes Made Easy TraumaDocument74 pagesNotes Made Easy TraumaMorshed Mahbub AbirNo ratings yet

- Incisional Hernia Open ProceduresDocument25 pagesIncisional Hernia Open ProceduresElias Emmanuel JaimeNo ratings yet

- Common Surgical IncisionsDocument17 pagesCommon Surgical IncisionsShaika-Riza SakironNo ratings yet

- Incisional HerniaDocument13 pagesIncisional HerniaMaya Dewi permatasariNo ratings yet

- Management of Complex Orbital Fractures: Article in PressDocument5 pagesManagement of Complex Orbital Fractures: Article in Pressstoia_sebiNo ratings yet

- Transition To Anterior Approach in Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty Learning Curve ComplicationsDocument7 pagesTransition To Anterior Approach in Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty Learning Curve ComplicationsAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- Orbitotomi MedscapeDocument9 pagesOrbitotomi MedscapeBonita AsyigahNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Trauma Lecture SurgeryDocument9 pagesAbdominal Trauma Lecture Surgerylarzy.larasumibcay27No ratings yet

- Kyestone Flaps PDFDocument9 pagesKyestone Flaps PDFDra. Bianca Ariza MoralesNo ratings yet

- El-Sayyad - Management of Burst Abdomen and Abdominal Wall ReconstructionDocument10 pagesEl-Sayyad - Management of Burst Abdomen and Abdominal Wall Reconstructionrhyzik reeNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument35 pagesUntitledGiselmar Soto DíazNo ratings yet

- Soft Tissue Management in Implant DentistryDocument37 pagesSoft Tissue Management in Implant DentistryAhmad AlhakimNo ratings yet

- Eaat 04 I 1 P 19Document4 pagesEaat 04 I 1 P 19allthewayhomeNo ratings yet

- Facial Fractures I Upper Two ThirdsDocument35 pagesFacial Fractures I Upper Two ThirdsJulia Recalde Reyes100% (1)

- The Palatal Advanced Flap: A Pedicle Flap For Primary Coverage of Immediately Placed ImplantsDocument7 pagesThe Palatal Advanced Flap: A Pedicle Flap For Primary Coverage of Immediately Placed ImplantsMárcia ChatelieNo ratings yet

- Endoskopik 2.brankialDocument5 pagesEndoskopik 2.brankialDogukan DemirNo ratings yet

- Akira Saito Et Al. (2009)Document4 pagesAkira Saito Et Al. (2009)Janardana GedeNo ratings yet

- Arthroplasty TodayDocument7 pagesArthroplasty TodaySanty OktavianiNo ratings yet

- LWBK836 Ch98 p1021-1030Document10 pagesLWBK836 Ch98 p1021-1030metasoniko81No ratings yet

- Jum 15608Document5 pagesJum 15608nessim zouariNo ratings yet

- J Neurosurg Case Lessons Article CASE2190Document4 pagesJ Neurosurg Case Lessons Article CASE2190chaiimaefrNo ratings yet

- Hindquarter IJOCDocument4 pagesHindquarter IJOCRyanAdnaniNo ratings yet

- Rib FractureDocument6 pagesRib FracturenasyilaputriNo ratings yet

- Clinical Maxillary Sinus Elevation SurgeryFrom EverandClinical Maxillary Sinus Elevation SurgeryDaniel W. K. KaoNo ratings yet

- The Ileoanal Pouch: A Practical Guide for Surgery, Management and TroubleshootingFrom EverandThe Ileoanal Pouch: A Practical Guide for Surgery, Management and TroubleshootingJanindra WarusavitarneNo ratings yet

- The MeniscusFrom EverandThe MeniscusPhilippe BeaufilsNo ratings yet

- Current Techniques in Canine and Feline NeurosurgeryFrom EverandCurrent Techniques in Canine and Feline NeurosurgeryAndy ShoresNo ratings yet

- A Manual of the Operations of Surgery: For the Use of Senior Students, House Surgeons, and Junior PractitionersFrom EverandA Manual of the Operations of Surgery: For the Use of Senior Students, House Surgeons, and Junior PractitionersNo ratings yet

- Ankle TappingDocument4 pagesAnkle TappingSenthilkumar ThiyagarajanNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Stretching ExsDocument1 pageAbdominal Stretching ExsSenthilkumar ThiyagarajanNo ratings yet

- Active Cycle Breathing Technique-Easy DemoDocument3 pagesActive Cycle Breathing Technique-Easy DemoSenthilkumar ThiyagarajanNo ratings yet

- Cervical ExerciseDocument1 pageCervical ExerciseSenthilkumar Thiyagarajan100% (1)

- Aids To The Examination of Peripheral Nervous SystemDocument67 pagesAids To The Examination of Peripheral Nervous SystemSenthilkumar ThiyagarajanNo ratings yet

- Anatomymnemonics PDFDocument28 pagesAnatomymnemonics PDFSenthilkumar ThiyagarajanNo ratings yet

- Postromedial Dic ProlapsDocument3 pagesPostromedial Dic ProlapsSenthilkumar Thiyagarajan100% (1)

- C:/Documents and Settings/student/Desktop/physiotherapy Protocol FOR HEMIPLEGIC PDFDocument13 pagesC:/Documents and Settings/student/Desktop/physiotherapy Protocol FOR HEMIPLEGIC PDFSenthilkumar ThiyagarajanNo ratings yet

- Above Knee Amputation Good One PDFDocument9 pagesAbove Knee Amputation Good One PDFSenthilkumar Thiyagarajan100% (1)

- Post Natal Exercise PrescriptionDocument8 pagesPost Natal Exercise PrescriptionSenthilkumar ThiyagarajanNo ratings yet

- Above Knee Amputation Exc PDFDocument5 pagesAbove Knee Amputation Exc PDFSenthilkumar ThiyagarajanNo ratings yet

- All Orthopedic TestsDocument7 pagesAll Orthopedic Testschandran2679No ratings yet

- Foxlite 2.0 Manual: Foxsupport@Geneko - RsDocument50 pagesFoxlite 2.0 Manual: Foxsupport@Geneko - RsFoxLiteNo ratings yet

- Rujukan OshaDocument22 pagesRujukan Oshahakim999No ratings yet

- Comparison of Horizontal Lip Pressure - R0Document2 pagesComparison of Horizontal Lip Pressure - R0AndiNo ratings yet

- IES MdijDocument5 pagesIES MdijAnonymous fFsGiyNo ratings yet

- Pinyin+character Stroke OrderDocument4 pagesPinyin+character Stroke OrderAlexandra SmlNo ratings yet

- Non-Destructive Testing For Non-Ferrous Materials Like Aluminium and Copper.Document9 pagesNon-Destructive Testing For Non-Ferrous Materials Like Aluminium and Copper.Raushan JhaNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan DLP F1 3 - 1Document1 pageDaily Lesson Plan DLP F1 3 - 1chezdinNo ratings yet

- Grammar - Unit 2 - in ClassDocument7 pagesGrammar - Unit 2 - in ClassJhomer Briceño EulogioNo ratings yet

- Peaktronics: Digital High-Resolution ControllerDocument12 pagesPeaktronics: Digital High-Resolution Controllerschmal1975No ratings yet

- (T), (D) or (Id) ? - "-Ed" Past Tense - English PronunciationDocument3 pages(T), (D) or (Id) ? - "-Ed" Past Tense - English PronunciationClaudioNo ratings yet

- Iae1 QPDocument3 pagesIae1 QPyaboyNo ratings yet

- History of Indian AdvertisingDocument13 pagesHistory of Indian AdvertisingdheepaNo ratings yet

- Albert Einstein Background and Early LifeDocument8 pagesAlbert Einstein Background and Early LifeMuhd HafizNo ratings yet

- Cha 2Document5 pagesCha 2ShammimBegumNo ratings yet

- Contemporary World Finals NotesDocument4 pagesContemporary World Finals Notesangelo subaNo ratings yet

- ACCO 101 Partnership Formation For Practice SolvingDocument2 pagesACCO 101 Partnership Formation For Practice SolvingFionna Rei DeGaliciaNo ratings yet

- Huawei eLTE Multimedia Critical Communication System Solution 高清印刷版 (刷新)Document8 pagesHuawei eLTE Multimedia Critical Communication System Solution 高清印刷版 (刷新)Alejandro RojasNo ratings yet

- Cepa-2012-Practice-Exam-Version-A AnswersDocument19 pagesCepa-2012-Practice-Exam-Version-A AnswersGeo KemoNo ratings yet

- Aspirin SynthesisDocument13 pagesAspirin SynthesisJM DreuNo ratings yet

- Post Test Bahasa InggrisDocument8 pagesPost Test Bahasa InggrisristyNo ratings yet

- ZKBiolock Hotel Lock System User Manual V2.0Document89 pagesZKBiolock Hotel Lock System User Manual V2.0Nicolae OgorodnicNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Exercise 1 Matlab Introducction: Name SectionDocument7 pagesLaboratory Exercise 1 Matlab Introducction: Name SectionDean16031997No ratings yet

- 501/423 Cable Gland Type: Flameproof and Increased SafetyDocument1 page501/423 Cable Gland Type: Flameproof and Increased Safetymadhan rajNo ratings yet

- Advanced Power Electronic Functionality For Renewable Energy Integration With The Power GridDocument17 pagesAdvanced Power Electronic Functionality For Renewable Energy Integration With The Power GridtomsiriNo ratings yet

- Igneous RockDocument9 pagesIgneous Rockdeboline mitraNo ratings yet

- Terberg Benschop Yt182 222 Yard Tractor BC 182 Body Carrier Electrical Wiring DiagramDocument22 pagesTerberg Benschop Yt182 222 Yard Tractor BC 182 Body Carrier Electrical Wiring Diagramkathleenterry260595mjz97% (31)

- The Return From One Investment Is 0.711 More Than The Other (Your Answer Is Incorrect)Document6 pagesThe Return From One Investment Is 0.711 More Than The Other (Your Answer Is Incorrect)Dolly TrivediNo ratings yet

- About Myself: - StrenghtsDocument2 pagesAbout Myself: - StrenghtsGabriela MoNo ratings yet

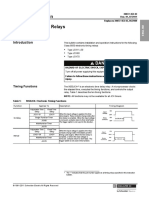

- Instruction Bulletin Electronic Timing Relays: Class 9050 Type JCKDocument4 pagesInstruction Bulletin Electronic Timing Relays: Class 9050 Type JCKKamran IbadovNo ratings yet