Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Perception and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions For Store Brands - Evidence From Malaysia

Uploaded by

Liew20200 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views32 pagesPerception and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands - Evidence From Malaysia

Original Title

Perception and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands - Evidence From Malaysia

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentPerception and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands - Evidence From Malaysia

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views32 pagesPerception and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions For Store Brands - Evidence From Malaysia

Uploaded by

Liew2020Perception and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands - Evidence From Malaysia

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 32

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 105

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 ISSN 19854064

Perceptions and Predictors of

Consumers Purchase Intentions for

Store Brands: Evidence from Malaysia

Siohong Tih* and Kean Heng Lee

ABSTRACT

This study examines consumers perceptions of retail store brands

and identifes the predictors of purchase intentions for the store

brands. To examine the proposed research model, two independent

samples are drawn. The frst sample consists of 120 responses

collected via mall intercept at a famous hypermarket retail chain

store, and the second sample consists of 120 responses also collected

using the mall intercept method at a supermarket chain store

in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Multiple regressions are used to test

the hypotheses. There are mixed results in relation to the tested

relationships. Perceived value for the money, perceived quality

variance, perceived price and perceived risk have a signifcant

impact on consumer purchase intention for the store brand in the

hypermarket sample. However, analysis using the supermarket

sample indicated that only perceived quality variance has a

signifcant impact on consumer purchase intention for the store

brand.

Keywords: Consumer Perception, Purchase Intention, Store Brand

JEL Classifcation: M31

1. Introduction

In an effort to increase their competitiveness in the market, large-scale

retailers have adopted a popular strategy, namely, developing their

own store brands. The retailers create their own brand either using

their store name for the brand or a separate brand name. These types

of brand names are known as store brands or private label brands.

* Corresponding author. Siohong Tih is an Associate Professor at the Graduate School of

Business, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 UKM, Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia, e-mail:

sh@ukm.my.

Siohong Tih and Kean Heng Lee

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 106

This strategy creates an opportunity for retailers to own, control, and sell

products under their own labels. Store brands play a vital role in retail

strategy. Today, store brands are available in diverse goods and services

ranging from household items to food and accessories. Store branded

products can be priced high or low depending on the retail strategy

(Baltas, 1997; Batra & Sinha, 2000; Dick, Jain & Richardson, 1997; Kremer

& Viot, 2012; Tifferet & Herstein, 2012; Zielke & Dobbelstein, 2007).

Store brands are highly important. The development of a store

brand is essential for improving revenue. From the retailers point

of view, a strong store brand might reduce marketing expenditures,

lead to cost savings and allow for fexible pricing (low or high prices,

depending on the targeted customers and margin). Store brands also

provide an opportunity for retailers to set their own prices during

promotion periods and thus compete with national brands. Moreover,

store brands may offer an opportunity to increase store traffc and build

store loyalty (Baltas, 1997; Baltas & Argouslidis, 2007; Dick et al., 1997;

Kremer & Viot, 2012; Tifferet & Herstein, 2012; Zielke & Dobbelstein,

2007). For instance, in the UK and the US, store brands are commonly

adopted by retailers (Kremer & Viot, 2012; Tifferet & Herstein, 2012).

Rahman et al. (2012) also stated that many retailers potentially develop

their own store brands to create loyal customers.

Demand for the store brand might encourage consumers to visit,

especially when they are familiar with the private label products,

because they are associated with particular retail stores. To create

and enhance customer loyalty, the brand may play an important role

in promoting products to the public, for example, communicating

the value for the money or the quality of the products. Consumers

willingness to purchase store branded products and loyalty towards the

brands depends on the consumers perception of critical factors such

as price, risk and quality (Dick et al., 1997; Rahman et al., 2012; Zielke

& Dobblestein, 2007).

The existing literature has examined the perception differences

and purchasing preferences between national and store brands (Batra

& Sinha, 2000; Broyles et al., 2011; De Wulf et al., 2005; Hoch & Banerji,

1993; Mieres, Martin & Gutierrez, 2006; Sethuraman & Cole, 1999).

Research has also examined the factors that influence consumer

decisions regarding retail stores and brands (Grandhi, Singh & Patwa,

2012; Kumar & Karande, 2000; Tifferet & Herstein, 2012; Zielke &

Dobbelstein, 2007). For example, Tifferet and Herstein (2012) examined

the predictors of store brand decisions, and Zielke and Dobbelstein

Perceptions and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands: Evidence

from Malaysia

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 107

(2007) studied customers willingness to purchase new store brands.

However, little attention has been given to the factors (i.e., price and

promotional sensitivities) infuencing consumers shopping behaviour

in different retail formats (Wang, Bezawada & Tsai, 2010). A closely

related theoretical reference would be studies on consumer behaviour

across channels or multi-channel research. It was found that consumers

behave differently across channels, such as using the Internet channel

for searching and visiting the retail outlet for actual purchasing (Piercy,

2012; Verhoef, Neslin & Vroomen, 2007; Konus, Verhoef & Neslin,

2008). With reference to the cross-channel literature, the key question is

whether consumer behaviour would be different across retail formats

(Wang et al., 2010). Researchers have initiated studies on consumer

behaviour across store formats. There are indications of behavioural

buying differences across retail formats with regards to demographics

and behavioural factors (Bustos-Reyes and Gonzalez-Benito, 2008;

Carpenter & Moore, 2006). Wang et al. (2010) mentioned that there are

limited studies that examine consumer purchasing behaviour across

retail formats. Therefore, we aim to contribute towards the existing

literature by examining consumer store brand purchase intention using

two samples, a supermarket and a hypermarket context, to complement

the previous studies that focus on a single retail format. It is expected

that the results will provide a useful reference for retailers in their

branding decisions. Specifcally, the objective of this study is to identify

the factors that infuence store brand purchase intentions across different

retail formats. The assumptions are that particular factors would have

an impact on store brand purchase intention and that by manipulating

these factors, retailers can better manage their investment in store brand

development and measure their return on store brand investment.

The following section of the paper synthesises the literature

on retail store brands and consumer shopping behaviour. Based on

the literature, the paper develops a research framework and specifc

hypotheses about the predictors of store brand purchase intention. The

paper then explains the methodology of an empirical study and the

results. The paper fnal section discusses the fndings of the study and

its theoretical as well as managerial implications.

2. Literature Review

A brand is defned as a distinguishing name, term, sign, symbol, or

any other unique combination of elements of goods or services that

Siohong Tih and Kean Heng Lee

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 108

identifes one frms products and sets them apart from the competition

(Aaker, 1991; Kotler et al., 2009, p.260; Solomon & Stuart 2002, p. 270).

Subsequently, store brands are defned as brands that are exclusive

to a particular retail store either produced by the retailer or supplied

by own-label suppliers (Baltas, 1997; Semeijn, Van Riel & Ambrosini,

2004). Store brands or private labels are owned by the retailers (Batra

& Sinha, 2000; Hoch & Banerji, 1993; Jin & Suh, 2005). In this paper, we

use the term store brand, which means store brand, private brand or

private label product. Store brands are commonly found in large-scale

retail chain stores, especially in the US and the UK (Dick et al., 1997;

Semeijn et al., 2004).

2.1 Retail store brands in Malaysia

Store brand development in the European and North American markets

is far beyond that in the Asia Pacifc markets. In Malaysia, for example,

store brands are still in an early stage of development (Nielsen, 2008).

However, there is an estimated growth rate of 30% year-on-year with

regards to the store brand market in Malaysia, which was valued at

RM240 million as of September 2008 (Nielsen, 2008). Worldwide, in 2012,

it was estimated that market share of store brand or private label sector

has reached 250 billion USD (Arslan, Gecti & Zengin, 2013). The growth

of store brand development and its adoption is supported by signifcant

increases in commodity prices and the downturn in the global economy.

For instance, grocery prices and food items have increased between 15

to 20 percent year-to-date. Thus, retailers looking for more control over

products opt to develop their own store brands (Nielsen, 2008).

Popular store branded items are products addressing consumers

basic and functional needs, such as paper, and commodity foods, such

as bottled water, sweetener and cooking oil (Nielsen, 2008; Phang, 2009).

Moreover, with the uncertainty in the global economy, Malaysians are

changing their grocery shopping habits. For example, in recent studies,

it was found that the majority of the respondents (eight out of ten

people) indicated that they only purchase essential items. Shoppers also

showed less loyalty and were looking for promotional items (Nielsen,

2009). This switching behaviour may provide an opportunity for store

brands to penetrate the local market. Today in Malaysia, store brands

are continuously growing in popularity, and the major retailers have

developed a range of products under their brands (Abdullah et al., 2012).

Retailers offering their private brands include Carrefour Malaysia,

IKEA, Isetan, Jusco, Parkson, Tesco Hypermarket Malaysia, Giant and

Perceptions and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands: Evidence

from Malaysia

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 109

Mydin Hypermarkets (Abdullah et al., 2012). In spite of store brand

strategy and opportunity, consumers purchase intentions towards store

brands remain largely untested and lack empirical support.

A review of the literature reveals that the factors infuencing

consumer purchase intentions for store brands may include price,

perceived quality variance, perceived value, brand loyalty, store image

and perceived risk associated with the store brand (Abdullah et al.,

2012; Baltas, 1997; Baltas & Argouslidis, 2007; Dick et al., 1997; Glynn &

Chen, 2009; Grewal et al., 1998; Jin & Suh, 2005). Zeilke and Dobbelstein

(2007) reported that other influential factors include the product

group, the positioning of the store brand, and attitudes toward store

brands. In addition, the conceptualisation of the price and perceived

quality relationship and its effect on consumers perceptions of value

and willingness to buy are studied as well as the effects of risk. Many

scholars have reported that when higher perceived risk is associated

with private brand purchase, it lowers the individuals perception of

value for the money (Aqueveque, 2006; Jin and Suh, 2005; Mitchell

and Harris, 2005; Semeijn et al., 2004). In brief, brand awareness, price,

quality, perceived risk and perceived value for the money have been

identifed as key factors that infuence consumer purchase intention of

store brands.

2.2 Predictors of store brand purchase intention

A store brand is a part of the retailers strategy. It is believed that

consumers attitude and judgements regarding store brands are

very subjective. Hence, perception is very important in determining

purchase intention. Price, perceived quality variation, store brand

familiarity, perceived risk and perceived value for the money are

among the predictors of store brand purchase intentions (Jin & Suh,

2005; Richardson, Jain & Dick, 1996). Price and product quality have

been well studied and identifed as key interrelated predictors of store

brand purchase intention (see Hoch & Banerji, 1993; Jin & Suh, 2005).

Quality perception is a critical element in purchase intention.

Richardson, Dick and Jain (1994) found that a poor perceived quality for

store brands partially offsets the favourable reaction to prices and leads

to a decrease in purchase intention. In consumer perception studies,

store brands might have different quality ratings (Beldona & Wysong,

2007; Sethuraman & Cole, 1999). Consumers might use extrinsic cues

such as brand name, price and packaging to judge the product quality

Siohong Tih and Kean Heng Lee

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 110

of a store brand (Richardson et al., 1996). This fnding is supported

by Hoch and Banerji (1993) and Semeijin et al. (2004). These authors

found that store brand purchase intention was lower when the quality

variability of the store brands was high. Furthermore, Semeijin et al.

(2004) also found that none of the store image factors could relieve the

risk of quality variance. The consumers who had experienced or used

store branded products might have higher quality perception towards

the brands (Beldona & Wysong, 2007). This fnding provided the insight

that retailers could promote their store brands by giving a free sample for

the frst trial. The trial might reduce the uncertainty and risk associated

with store brands. Doubt regarding store brands might relate to the lack

of advertising and lower prices for store branded products (Bettman,

1973; Batra & Sinha, 2000; Richardson et al., 1996).

In addition, store brand awareness, perceived risk and perceived

value for the money are also related to store brand purchase intention.

For store brand awareness or familiarity with store brands, it is found

that consumers have more favourable views towards the store branded

products that they are familiar with (Richardson et al., 1996). Perceived

risk in terms of the lower consequences of making a mistake had an

impact on store brand purchase intention (Batra & Sinha, 2000).

Evidence showed that perceived higher value for the money had a

positive impact on store brand proneness (Richardson et al., 1996). Too

large a price gap may adversely affect the perception of value and quality

offered by store brands. Consequently, it is expected that a reduction

in the price gap between the national and store brands will infuence

perceptions of store brand quality. All of these situations suggest that

store brands pose a purchasing risk in the eyes of the consumer. The

risk is due to uncertainty with respect to knowing the manufacturers

of these store brands. This risk is amplifed by the fear of the frst trial.

Furthermore, the manifestation of the perception of risk depends on

the consumers knowledge of the store brand. Store brand purchase

intention increases when the perceived risk that the consumer associates

with the store brand decreases, thus building confdence in the store

brand product quality (Batra & Sinha, 2000; Dick et al., 1995).

These studies have supported a few key predictors of store brand

purchase intentions or private label proneness. There is, however, a

question of whether these factors have a direct or an indirect impact on

store brand purchase intention in the context of developing countries

such as Malaysia because retailers in developing countries also have

initiated their store brands. Owning store brands enable retailers to enjoy

Perceptions and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands: Evidence

from Malaysia

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 111

higher margin (Abdullah et al., 2012) and might enhance retailer brand

image (Kremer & Viot, 2012). Introducing store brands to developing

countries provide opportunity for growth (Grandhi, Singh & Patwa,

2012). It is important to examine whether the similar determinant factors

would explain store brand purchase intention in developing country

context. Thus, this study aims to provide some useful information

for retailers to ease their store brand management and allow them

to understand the relationships between key variables such as price,

quality, awareness, risk, value for the money and purchase intention. In

particular, identifying key predictors of store brand purchase intention

would allow the retailer to manipulate particular variables within their

strategy formulation.

2.3 Consumer Shopping Behaviour across Retail Formats

Several studies examine consumer shopping behaviour across channel

and retail formats (Hsiao, Yen & Li, 2012; Konus, Verhoef & Neslin,

2008; Piercy, 2012; Verhoef, Neslin & Vroomen, 2007; Wang, Bezawada

& Tsai, 2010). From the multi-channel literature, consumers tend to

search information through the Internet channel and purchase the

product at a physical retail outlet (Konus et al., 2008; Verhoef et al.,

2007). Research on the retail format choice examines predictors and the

desired store attributes of different retail formats such as department,

specialty and discount stores (Carpenter & Brosdahl, 2011; Finn and

Louviere, 1990; Yavas, 2003). Studies across retail formats indicated that

consumers from different demographic and behavioural backgrounds

show different shopping behaviours across retail formats (Bustos-Reyes

& Gonzalez-Benito, 2008; Carpenter & Moore, 2006; Piercy, 2012; Wang

et al., 2010). For example, shopper demographic characteristics such as

age, gender, occupation, education, income, family size and distance

to the retail outlet are related to retail format choice decisions (Prasad

& Aryasri, 2011). Nevertheless, expert and novices shoppers would

consider the utilitarian value when involve in multi-channel shopping

(Hsiao, Yen & Li, 2012).

Wang et al.s (2010) study compares consumer price and promotion

sensitivities in brand choice behaviour between the supermarket and

the mass merchandiser retail formats by product category. In general,

consumers have lower price but higher promotional sensitivity in the

mass merchandiser format. Therefore, a co-branding strategy might

beneft the merchandiser. The consumers intrinsic preference for

Siohong Tih and Kean Heng Lee

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 112

national brands is obvious in the mass merchandiser outlet relative to

the supermarket for food items. Their study also indicated that higher

income consumers were less sensitive to price and promotion activities.

Married households were more sensitive towards promotion, whereas

households with a larger family size were sensitive towards price but

not promotion.

Research on male shoppers indicated that there are distinctive

predictors among male shoppers across different retail format choices

such as department stores, discounters, category killers, dollar stores

and online retail stores (Carpenter & Brosdahl, 2011). In particular, the

predictors of departmental store patronage were brand loyalty, price

competitiveness, shopping enjoyment and recreation, knowledgeable

salespeople and well-known brands. The predictors of discount store

patronage were product selection, price competitiveness, quality of

products and price. Women displayed more positive cross-channel

behaviour than men (Piercy, 2012). Piercy (2012) also found that highly

educated shoppers had less positive behaviour towards cross-channel

shopping.

Although from the literature, there are indications of consumer

differences across retail formats, there are limited studies that directly

examine the store brands introduced by these retail outlets or that

attempt to explain consumers intention to purchase these store branded

products. Carpenter and Brosdahls (2011) study examines predictors

of retail format choice but not store brand purchase intention. Peircy

(2012) examines positive and negative cross-channel behaviour without

considering brand effect.

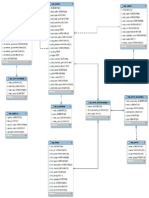

3. Research framework and hypotheses

The proposed research model is based on the conceptualisation of the

predictors of store brand purchase intention. The proposed model is

presented in Figure 1; it consists of fve independent variables and

one dependent variable. The independent variables include perceived

price, perceived quality variance, perceived value for the money, store

brand awareness and perceived risk. These variables were included in

this study because it is suggested that they have some direct or indirect

impact on store brand purchase intention and that they are relevant

to the Malaysian retail context. The dependent variable is store brand

purchase intentions. In this study, the hypothesised direct relationships

are tested across two samples to examine the consistency of the fndings.

Perceptions and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands: Evidence

from Malaysia

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 113

Perceived Price

Perceived Quality

Variance

Perceived Value

for the Money

Store Brand

Awareness

Store Brand

Purchase

Intention

Perceived Risk

3.1 Perceived Price and Store Brand Purchase Intention

Prices are always the first extrinsic cue for consumers, and how

consumers evaluate the price variable might infuence their store

brand purchase intention (Abdullah et al., 2012; Baltas, 1997; Baltas &

Argouslidis, 2007; Zielke & Dobbelstein, 2007). Prices are emphasised

by those who are price sensitive. As described in Nielsens (2008; 2009)

study, perceived price has been identifed as having the strongest

relationship with propensity towards a store brand. This fnding has

also been reported by Glynn and Chen (2009). Price is the key predictor

of store brand purchase decisions in most product categories. Thus, the

following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Perceived price is related to store brand purchase intention

Store brand quality is the most debatable element. The literature shows

that the perceived quality of the store brand is subjective. In addition,

quality might be part of the perceived value for the money component

(see Abdullah et al., 2012; De Wulf et al., 2005; Dick et al., 1995; Jin & Suh,

2005; McDougall & Levesque, 2000; Mieres et al., 2006; Zeithaml, 1988).

In Baltas and Argouslidiss (2007) study, educated and high-income

Figure 1 Research Model

Siohong Tih and Kean Heng Lee

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 114

individuals also consume store-branded products, and they might

indirectly compare quality with price, thus considering the overall value

of the purchase. Although perceived quality might interact with other

variables, it is suggested that the perceived quality of the store brand

was the most important predictor of store brand purchase intention

(Levy & Gendel-Guterman, 2012). Therefore it is proposed that:

H2: Perceived quality variance is related to store brand purchase

intention

Value refers to the perceived quality relative to the price or the total

benefts relative to the total costs perceived by the customers (Jin & Suh,

2005; McDougall & Levesque, 2000; Zeithaml, 1988). Thus, the perceived

value implies ones relative consideration of the quality versus the price

of an offering (Dick et al., 1995; Richardson et al., 1996). Store brand

prone shoppers perceive store brands as offering a greater value for the

money (Dick et al., 1995). In general, consumers are prone to brands

that offer greater value for the money. The higher the perceived value

for the money associated with store brands, the higher the tendency to

purchase store branded products (Jin & Suh, 2005; Richardson et al.,

1996; Zielke & Dobbelstein, 2007). Jin and Suh (2005) found that value

consciousness had a direct and indirect impact on store brand purchase

intention dependent on product category. However, in this study, we

examine the direct impact of perceived value for the money on store

brand purchase intention.

In the literature, it is also illustrated that price, quality and value are

abstract elements (see De Wulft et al., 2005; Dick et al., 1995; Jin & Suh,

2005; McDougall & Levesque, 2000; Mieres et al., 2006; Zeithaml, 1988).

For example, image transfer in terms of the store brands image and the

retailer brand image might involve price, supply and value dimensions

(Kremer & Viot, 2012). There is a tendency for price and quality to be

implied in value for the money. Considering the abstract and complex

relationships between these variables, we would prefer to examine all

of the potential direct relationships between price, quality and value

for the money on purchase intention (Dick et al., 1995; Richardson et

al., 1996). Taking the above-mentioned considerations into account, the

following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Perceived value for the money is related to store brand purchase

intention

Perceptions and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands: Evidence

from Malaysia

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 115

3.2 Store Brand Awareness and Store Brand Purchase Intention

Store brand awareness can be defned as the likelihood that a store

brand will appear in the consumers mind and the length of time this

memory will stay, which means familiarity with the brand and strong

brand recognition (adapted from Keller, 1993; De Wulf et al., 2005; Yoo,

Donthu & Lee, 2000). It was found that familiarity with store brands has

an impact on store brand proneness (Abdullah et al., 2012; Richardson

et al., 1996). Consumers tend to have a more favourable perception

towards the store brands that they are familiar with and to evaluate

these more highly in terms of quality and value for the money. Mieres

et al.s (2006) study also indicated that a greater familiarity with store

brands would have a more positive infuence on their perceived risk.

As the awareness of the store brands increases, it may become one of

the options in the consumers considerations for purchase. De Wulf

et al. (2005) suggest that high store brand awareness will increase the

likelihood that a brand will be recalled when it comes to a purchase

evaluation. Consequently, higher store brand awareness may increase

the chance or possibility that consumers will decide to purchase store

branded products because they may recall store brands when it comes

to brand evaluation. Hence, the following is hypothesised:

H4: Store brand awareness is related to store brand purchase intention

3.3 Perceived Risk and Store Brand Purchase Intention

In this study, perceived risk refers to fnancial risk, and it relates to the

cost relative to an individuals fnancial resources (Mitchell & Harris,

2005). Perceived risk is dependent on the amount of information available

to the consumer about store brands. A store brand purchase is more

likely when the consumer is confdent that they can obtain satisfactory

performance (Baltas, 1997). The perceived risks associated with the

store brand are an important factor evaluated by the consumer and

they infuence the purchase intention of the store brand. Furthermore,

non-store brand prone shoppers were worried about fnancial risk (Dick

et al., 1995). If the risk associated with the store brand is low, it may

increase the likelihood of purchasing store branded products. In other

words, store brand purchase intention increases when perceived risk,

especially fnancial risk, is reduced (Batra & Sinha, 2000; Richardson et

al., 1996; Zielke & Dobbelstein, 2007). With reference to this literature,

the following is hypothesised:

Siohong Tih and Kean Heng Lee

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 116

H5: Perceived risk is related to store brand purchase intention

4. Methodology

The study population for this research is retail consumers of store

brands in Malaysia. There are several store brands available in the

Malaysian market such as Giant, Carrefour and Tesco (Rahman et al.,

2012). The non-probability sampling technique is adopted in this study.

The non-probability sampling technique is used in similar studies

(Mandhachitara, Shannon & Hadjicharalambous, 2007; Tifferet and

Herstein, 2012) and is acceptable when the generalisation concern is

low (Churchill, 1991; Diamantopoulos and Schlegelmilch, 1997).

This study employs a mall intercept survey method for data

collection. Two samples were collected to test the proposed model.

The frst sample was collected at a hypermarket retail chain store,

and the second sample was collected at a supermarket retail outlet.

Both retail chain stores have introduced their own store brands. The

actual names of these retail chain stores are not disclosed in this paper.

However, the actual names of these retail stores and its store brands

were used in the questionnaire. These retail chain stores are selected

because they have each opened more than 20 stores nationwide in

Malaysia. Furthermore, the selected supermarket retail store brand

was selected as one of Malaysias 30 most valuable brands (The Edge,

2009), thus indicating the appropriateness of using these store brands.

These retail chain stores have been selling their store brands for some

years. Therefore, it is possible to measure the consumers perceptions

of these store brands. Customers of these two retail stores were invited

to participate in this study.

The sampling locations were the retail store at Ampang

(hypermarket) and Taman Connaught (supermarket), Malaysia. The

shoppers were intercepted during their visit to these retail stores.

Convenience quota sampling was used, aiming at a sample size of 250

with 125 shoppers representing each retail store. The targeted sample

size is relatively small because this is a small-scale survey focusing on

examining relationships between variables instead of the generalisation

of results.

A voluntary participative approach was used. The shoppers

were approached by interceptors and asked to complete a structured

questionnaire. The shoppers who indicated their willingness to

participate were given the questionnaire; for the participating shoppers,

Perceptions and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands: Evidence

from Malaysia

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 117

an instruction emphasised that there are no correct or incorrect answers;

only your personal opinions matter to minimise possible response bias.

The questionnaires were distributed in the feld and retrieved once the

shoppers had completed them.

A structured questionnaire was developed to collect the desired

data in this study. The questionnaire consisted of three sections and was

designed to extract the shoppers responses regarding their perception

towards store brands and their purchase intention. Firstly, a series of

questions to capture their perceptions of the store brands were included.

Next, the respondents were asked about their future purchase intention

for store brands. Finally, the respondents were asked to provide socio-

demographic information. A few rounds of pre-testing were held to

make sure that the items in the questionnaire were understandable

and clear.

4.1 Measurement

Multi-item scales from previous research were adopted or adapted

to measure the variables included in the proposed model. A pool of

measurement items were examined and revised to ft the Malaysian retail

store context. The brand awareness and perceived price measurement

items were adapted from Yoo et al. (2000). Perceived value for the

money was adapted from Dobbs et al.s (1991) measurement instrument.

Measurement items for perceived quality variance were adapted from

prior studies (Jin & Sternquist, 2003; Mieres et al., 2006; Yoo et al., 2000).

Perceived risk was measured using a scale developed by Richardson et

al. (1996) and Mieres et al. (2006). The measurement items for purchase

intention were developed by the authors with reference to the previous

literature (Jin & Suh, 2005).

The full set of measurement items are presented in the Appendix. In

particular, we measure the store brand but not the retail store. The store

brands are considered without specifying the product categories. This

approach is not uncommon in empirical research (Kremer & Viot, 2012).

In addition, we only use the perceived measure. It was suggested that

the perceived measure plays a signifcant role in consumer psychology

because studies have shown that consumer perceptions have an impact

on consumer behaviour (Yoo et al., 2000). All of the variables were

measured using established fve-point Likert scales with 1 meaning

Strongly Disagree and 5 meaning Strongly Agree or vice versa for

negative items (DAstous & Gargouri, 2001). In terms of the analysis, a

Siohong Tih and Kean Heng Lee

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 118

preliminary statistical analysis on the scales reliability and correlation

were performed. Then, multiple regressions were used to test the

hypothesised relationships (Hair et al., 1998).

5. Empirical Results

This section presents the results of the statistical analyses and testing

of the hypotheses regarding consumer perception and the purchase

intention for store brands. The SPSS software is employed for data

analysis. Firstly, a scale reliability test and correlation were performed,

followed by the testing of the hypothesised relationships.

5.1 Sample Characteristics

A total of 240 completed responses were included in the fnal sample.

These responses were collected at a hypermarket and a supermarket

retail store. Table 1 provides a detailed description of the socioeconomic

characteristics of the samples. For the frst sample, responses were

collected at a hypermarket; this sample was 60.0% female and 40.0%

male. Approximately 50.0% of the respondents were in the age range of

25-31 years. A total of 70.0% of the respondents were Chinese shoppers,

22.5% were Malay, and approximately 4.2% and 3.3% were Indian and

other races, respectively. Approximately half of the samples (50.0%)

were from the RM2,000 to RM4,000 income group, followed by the

RM1,000 to RM2,000 (23.4%) income group. The analysis indicated

that over half of the respondents (76.7%) had four or more family

members. The profle also indicated that 75.0% of the respondents had

obtained a diploma or a university degree and most of them (82.5%)

were employed.

The second sample was collected at a supermarket chain store and

was 58.3% female and 41.7% male respondents. Most of the respondents

were 38 years old or below (85.0%). Malay and Chinese shoppers were

the dominant races in this sample, with 47.5% and 35.8%, respectively.

Most of the shoppers were from the RM2,000 to 4,000 income group,

with 33.3%, followed by the RM1,000 to RM2,000 (31.7%) income

group. In addition, most of the respondents came from a large family

with four or more family members (73.3%). Most of the respondents

had either a diploma or a university degree (61.6%). A small portion

of the respondents had only attended secondary school (21.7%) or pre-

university study (15.0%). In the sample, 15.0% were students and 74.1%

Perceptions and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands: Evidence

from Malaysia

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 119

Variables First Sample

(Hypermarket)

Second Sample

(Supermarket)

Frequency Percent Frequency Percent

Gender

Male 48 40.0 50 41.7

Female 72 60.0 70 58.3

Age

18-24 years 17 14.2 33 27.5

25-31 years 57 47.5 46 38.3

32-38 years 20 16.7 23 19.2

39-45 years 13 10.8 9 7.5

46-52 years 10 8.3 8 6.7

>52 years 3 2.5 1 0.8

Race

Malay 27 22.5 57 47.5

Chinese 84 70.0 43 35.8

Indian 5 4.2 9 7.5

Others 4 3.3 11 9.2

Income (Monthly) in

Ringgit Malaysia

<500 4 3.3 9 7.5

500-1000 4 3.3 20 16.7

1001-2000 28 23.4 38 31.7

2001-3000 33 27.5 24 20.0

3001-4000 27 22.5 16 13.3

4001-5000 11 9.2 6 5.0

>5000 13 10.8 7 5.8

Family Size (number of

occupants)

1 2 1.7 3 2.5

2 13 10.8 9 7.5

3 13 10.8 20 16.7

4 33 27.5 25 20.8

5 30 25.0 42 35.0

>5 29 24.2 21 17.5

Educational

No schooling 2 1.7 0 0.0

Primary school 1 0.8 2 1.7

Secondary school 23 19.2 26 21.7

Pre-university 4 3.3 18 15.0

Diploma 32 26.7 37 30.8

University 58 48.3 37 30.8

Occupation

Student 6 5.0 18 15.0

Not employed 1 0.8 2 1.7

Self-employed 14 11.7 11 9.2

Employed 99 82.5 89 74.1

Table 1 Profle of the respondents

Siohong Tih and Kean Heng Lee

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 120

were employed adults. The number of students may be driven by the

fact that there is a college near the retail store. Hence, more students

were visiting the store to purchase their necessities.

Due to the non-probability sampling technique, the sample was not

fully representative. However, the characteristics of the respondents in

the study are similar to the characteristics of retail store brand shoppers.

In this study, the sample consists of more females than males. This

result is consistent with previous research related to store brands. For

example, in a study involving 206 shoppers at a chain store, 71% of the

respondents are female (Levy & Gendel-Guterman, 2012). The majority

of the respondents are employed except in sample two; in this sample,

there are more students because the retail store is near a college. Store

brand research involving students is not uncommon. Students, based on

their needs for cognition, interpret relevant information in a meaningful

and integrated way and also show an inclination to purchase store

brands (Tifferet & Herstein, 2012). The profle of the respondents in this

study also includes representatives from different age groups, and the

majority of them were educated in secondary school and above (Levy

& Gendel-Guterman, 2012).

5.2 Scale Reliability

Cronbachs alpha values are used to indicate the reliability of each

variable. Cronbachs alpha is a measure of internal consistency based

on the average inter-item correlation. The Cronbachs alpha coeffcient

of each variable is shown in Tables 2 and 3. The Cronbachs alpha

reliability for each of the six scales (brand awareness, perceived price,

perceived quality variance, perceived value for the money, perceived

risk, and purchase intention) are 0.70 or higher, thus indicating that

they are appropriate for further analysis (Yoo et al., 2000). Hence, 23

items were retained: four items for store brand awareness; two items

for perceived price; six items for perceived quality variance; fve items

for perceived value for the money; three items for perceived risk; and

three items for purchase intention. The correlation results indicated

that most of the tested variables are related with the exception of price

and purchase intention in the frst sample (hypermarket) and brand

awareness and purchase intention in the second sample (supermarket).

Therefore, a subsequent regression analysis was conducted to examine

the hypothesised relationships.

Perceptions and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands: Evidence

from Malaysia

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 121

No of Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6

Item

2 Perceived Price 33.0 .80 [.78]

6

Perceived Quality

Variance

2.97 .61 .28** [.80]

4 Brand Awareness 3.55 .88 .31** .46* [.85]

3 Perceived Risk 3.32 .91 .043 .29** .11 [.88]

5

Perceived Value

for the Money

3.35 .70 .47** .65** .33** .27** [.85]

3 Purchase Intention 2.72 .93 .16 .58** .30** .34** .59* [.89]

** Correlation is signifcant at the 1% level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is signifcant at the 5% level (2-tailed).

Numbers in diagonal represent Cronbachs Alpha values

No of Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6

Item

2 Perceived Price 3.42 .91 [.71]

6

Perceived Quality

Variance

3.15 .59 .34** [.76]

4 Brand Awareness 3.58 .79 .35** .44** [.78]

3 Perceived Risk 3.34 .89 .05 .31** .03 [.76]

5

Perceived Value

for the Money

3.51 .67 .59** .57** .45** .28** [.84]

3 Purchase Intention 2.94 .86 .29** .67** .30** .18 .48** [.81]

** Correlation is signifcant at the 1% level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is signifcant at the 5% level (2-tailed).

Numbers in diagonal represent Cronbachs Alpha values

5.3 Result of Perception on Store Brand

To determine store brand perception, the means and standard

deviations of the studied variables were examined. In the frst sample

(hypermarket), the purchase intention for the store brand is below the

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics, Reliabilities and Correlations

Hypermarket Sample

Table 3 Descriptive Statistics, Reliabilities and Correlations

Supermarket Sample

Siohong Tih and Kean Heng Lee

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 122

mid-point of 3 based on a 5-point rating scale (mean=2.72, SD=.93).

Similarly, the mean score for perceived quality is 2.97 (SD=.61).

However, the store brand awareness is higher than the mid-point of 3,

with a mean score of 3.55 (SD=.88). The perceived price, risk and value

for the money are in the same range, which is approximately 3.30 based

on a 5-point scale (see Table 4).

With regards to the second sample (supermarket), the purchase

intention for the store brand was also slightly below the mid-point of

3, with a mean score of 2.94. The mean scores for the other variables

were all above the mid-point of 3, and the mean score for store brand

awareness and perceived value for the money were approximately 3.50,

followed by perceived price (mean=3.42), perceived risk (mean=3.34)

and perceived quality (mean=3.15).

Table 4 Perception of store brand

First sample

(Hypermarket)

Second sample

(Supermarket)

Variable Mean SD Mean SD

Purchase Intention 2.7278 .93384 2.9444 .86679

Store Brand Awareness 3.5563 .88371 3.5854 .79751

Perceived Price 3.3042 .80517 3.4292 .91278

Perceived Quality Variance 2.9750 .61897 3.1542 .59768

Perceived Risk

a

3.3250 .91920 3.3417 .89345

Perceived Value for the

Money

3.3583 .91920 3.5100 .67704

Note: Sample sizes: 120 responses collected at a hypermarket and 120 responses collected

at a supermarket.

a

Scoring of this item is reversed so that higher scores indicate more positive responses

In both samples, the mean score was not high because none of

the mean scores achieve 4 points on a 5-point scale. This score might

indicate that the respondents perception of those store brands was

not very high. With reference to the results of this study, one plausible

explanation is that the awareness of the store brand did not achieve a

high level, not achieving a score of 4 based on a 5-point scale. A lower

level of brand awareness might be refected in other associated variables

such as perceived price, quality and value.

Perceptions and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands: Evidence

from Malaysia

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 123

5.4 Hypotheses Testing of Relationships

This section presents the results related to the hypotheses testing. Each

of the hypotheses was examined separately. The hypotheses were tested

using a regression analysis where store brand awareness, perceived

price, perceived quality variance, perceived risk and perceived value

for the money were classifed as the predictive variables and store brand

purchase intention as the dependent variable.

Testing of hypotheses

The result of the regression analysis is presented in Table 5. With

reference to the regression results using the frst sample (hypermarket),

the adjusted R Square value shows that the model accounts for 42.6%

of the variance (adjusted r

2

=0.426). Among the tested variables, the

perceived value for the money (=0.428) and perceived quality variance

(=0.263) have a statistically signifcant effect on purchase intention.

Thus, hypotheses H3 and H2 were supported. Moreover, hypotheses

H5 and H1 that perceived risk (=0.143) and perceived price (=-0.144)

have an effect on purchase intention (p<0.10) were partially supported.

Brand awareness was not signifcantly related to purchase intention for

the store brand. Hypothesis H4 was not supported. The negative sign of

the value is due to the statements used to measure the perceived price.

The two statements were (i) the price of the X store brand product is

low; and (ii) the price of the X store brand product is below the market

average. Therefore, the lower scores for these statements means that

consumer perception regarding the price is positive and yields higher

purchase intention. This result means that a positive perception towards

price increases the tendency to purchase store branded products.

In the hypermarket context, similar to the findings in the

literature, perceived value for the money, perceived quality variance,

perceived price and risk were all signifcant predictors of store brand

purchase intention (Batra & Sinha, 2000; Dick et al., 1995; Jin & Suh,

2005, Richardson et al., 1996). However, brand awareness was not a

signifcant predictor. As discussed in the literature, store brand might

have an indirect relationship with purchase intention (De Wulf et al.,

2005; Richardson et al., 1996; Mieres et al., 2006). Another plausible

explanation is that brand awareness might be a moderating factor

instead of a direct predictor. Wang and Yangs (2010) study found that

the relationship between brand credibility and purchase intention is

moderated by brand awareness.

Siohong Tih and Kean Heng Lee

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 124

The regression analysis using the second sample (supermarket)

shows different results. The adjusted R Square value shows that the

model accounts for 44.2% of variance (adjusted r

2

=0.442). Among the

tested variables, only perceived quality variance has a statistically

signifcant effect on purchase intention (=0.613), thus supporting

hypothesis H2. Other variables such as perceived price, perceived

value for the money, brand awareness and perceived risk were not

signifcantly related to purchase intention. Therefore, hypotheses H1,

H3, H4 and H5 were not supported based on the data of the second

sample (supermarket).

First Sample

(Hypermarket) Store

Brand Purchase

Intention

Second Sample

(Supermarket) Store

Brand Purchase

Intention

R 0.671 0.682

r

2

0.450 0.465

Adjusted r

2

0.426 0.442

Std.Error of the Estimate 0.70773 0.64749

F 18.637*** 19.851***

Store Brand Awareness

Unstandardised coeffcient 0.072 -0.047

Standardised coeffcient 0.069 -0.043

Perceived Price

Unstandardised coeffcient -0.167 0.009

Standardised coeffcient -0.144 0.010

Perceived Quality Variance

Unstandardised coeffcient 0.396 0.889

Standardised coeffcient 0.263** 0.613***

Perceived Value for Money

Unstandardised coeffcient 0.569 0.204

Standardised coeffcient 0.428*** 0.159

Perceived Risk

Unstandardised coeffcient 0.145 -0.057

Standardised coeffcient 0.143* -0.059

***, ** and * represent signifcance (two-tailed) at 1%, 5%, and 10% levels respectively.

Table 5: Factors affecting purchase intention of store brand

Perceptions and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands: Evidence

from Malaysia

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 125

Previous researches across retail formats shows that consumer-

behaviour varies across retail formats (Bustos-Reyes and Gonzalez-

Benito, 2008; Carpenter & Moore, 2006; Wang et al., 2010). This fnding

might explain why there are different predictors for store brand purchase

intention with regards to hypermarket and supermarket retail formats as

found in this study. Furthermore, in the literature, consumer behaviour

and acceptance of a product or brand is also infuenced by brand image,

self-image congruity, brand credibility and brand origin (Dolich, 1969;

Li, Wang & Yang, 2011; Rahman et al., 2012). For example, a store brand

with a good image and high self-image congruity is more attractive to

customers (Dolich, 1969; Rahman et al., 2012). Brand credibility, brand

origin and self-image congruity are also infuential factors leading to

consumer purchase intention. For example, brand credibility has a

strong direct impact on the consumer purchase intention of a brand (Li,

Wang & Yang, 2011). Brand preference is also infuenced by brand image

belief as a result of brand advertisement endorsers. In particular, brand

purchase intention rather than brand attitude is signifcantly affected

by brand image belief when social consumption is evoked and there is

a ft between brand and self-image congruity (Batra & Homer, 2004).

6. Discussion

One of the primary contributions of this research relates to the use

of two different samples collected at hypermarket and supermarket

retail outlets to test the hypothesised relationships. The use of different

samples allows for cross-validation of the proposed relationships. Thus,

the results provide evidence of variations across different store brands

and allows for the examination of customers perceptions and purchase

intentions with regards to different retail contexts.

With regards to our study objectives of identifying perception and

direct predictors of store brand purchase intention, fve predictors of

store brand proneness, i.e., brand awareness, perceived price, perceived

quality variance, perceived value for the money and perceived risk, were

examined. In the previous literature, there is some evidence that store

brand awareness or familiarity with store brands has a direct or indirect

impact on store brand proneness (Richardson et al., 1996; Mieres et al.,

2006). In this study, it was found that store brand awareness did not have

a direct impact on store brand purchase intention. Perhaps the indirect

relationship is prominent as suggested in literature (De Wulf et al.,

2005; Mieres et al., 2006) either via perceived risk or a higher recall rate.

Siohong Tih and Kean Heng Lee

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 126

Another plausible explanation is that the store brand awareness

among these retail store brands was not very high: none of the store

brands achieved 4 points based on a 5-point rating scale. Perhaps an

important frst step is to build greater consumer awareness of store

brands by increasing familiarity with them. Familiarity with store

branded products may be increased via education, taste tests, or the

distribution of free samples whenever there is a new store branded

product being launched (Richardson et al., 1996).

Perceived price only exerts a small contribution to store brand

purchase intention. The relationship between perceived price and

purchase intention was only partially supported in the frst sample.

Surprisingly, perceived price was not related to purchase intention

when the relationship was tested in the second sample collected at a

supermarket retail outlet. This non-associative relationship was also

reported in Jin and Suhs (2005) study with regard to the home appliance

product category. This fnding is inconsistent with some earlier research

fndings where price was the most important reason for store brand

purchase (Baltas, 1997; Baltas & Argouslidis, 2007; Zielke & Dobbelstein,

2007). In addition, if consumers associate the store brand with a lower

price, the likelihood of purchase was reduced. Therefore, retailers should

be careful when adopting lower price strategies. This phenomenon

requires further investigation to assist retailers in their penetration

strategies in emerging markets such as Malaysia, Indonesia and China.

Perceived quality variance is a key predictor of store brand

purchase intention, which means that a high perception of the quality

of store brands leads to a higher tendency to purchase store branded

products regardless of the retail outlet. This fnding is consistent with

Levy and Gendel-Gutermans (2012) study. They found that perceived

quality is an important predictor of store brand purchase intention.

Similarly, Jin and Suhs (2005) study indicated that the quality of the

store brand is much more important than a lower price strategy in

determining the store brands market share for home appliances. Other

supporting literature includes Batra and Sinha (2000) as well as Glynn

and Chen (2009).

In this study, perceived value for the money is a significant

predictor for purchase intention when the hypothesised relationship

was tested in the frst sample (hypermarket) but not in the second

sample (supermarket). In previous research, perceived value for money

Perceptions and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands: Evidence

from Malaysia

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 127

was found to have an effect on store brand proneness when the study

compared national or manufacturing brands with store brands (Jin

& Suh, 2005; Richardson et al., 1996). Another view is that perceived

value for money might have an indirect relationship with store brand

proneness (Jin & Suh, 2005). Therefore, it is yet to be confrmed whether

perceived value for money has an indirect relationship with store brand

purchase intention. Based on the fndings for the direct relationships

in this study, Malaysian consumers might purchase store branded

products due to their perceived higher value for the money or because

of the perceived higher quality.

Consumers who lack experience with store branded products are

likely to view them with doubt and may consider them to be a risky

choice. This study shows that the relationship between perceived risk

and purchase intention was partially supported in the frst sample

(hypermarket) but not in second sample (supermarket) even though

both store brands mean perceived risk score was 3.3 on a 5-point scale.

This result means that the respondents might consider the perceived

risk when buying store branded products. The previous literature also

suggests that perceived risk is one of the predictors of store brand

purchase intentions (Batra & Sinha, 2000; Richardson et al., 1996; Zielke

& Dobbelstein, 2007).

7. Conclusion

This study provides useful information to enhance the understanding

of the key predictors of store brand purchase intentions. First, the study

identifes the perception of store brands in terms of the perceived price,

quality, value for money, brand awareness and perceived risk as well

as store brand purchase intention.

Second, perceived value for money and perceived quality variance

are important factors for attracting consumers towards store branded

products. Perceived price and perceived risk management also increase

the consumers likelihood of purchasing store branded products and

should not be ignored. It is important to note that the prominent

predictor is perceived quality variance, which means that a high quality

image should be created to attract the consumption of store branded

products. It is suggested that store brand owners might need to explore

other indirect or mediating factors because the direct relationships are

not consistent across samples.

Siohong Tih and Kean Heng Lee

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 128

7.1 Theoretical Implications

The theoretical implication of this study is that it extends the current

explanation of consumer behaviour across retail formats (Carpenter

and Brosdahl, 2011). This study indicates that consumers behave

differently towards different store brands (i.e., store brands introduced

by a hypermarket and a supermarket). The results of this study indicate

that some variables such as price, value, brand awareness and perceived

risk were not strong direct predictors of store brand consumption when

the store brand is introduced by a supermarket, although the previous

literature has demonstrated that these variables have some impact on

store brand purchase intention (Baltas, 1997; Baltas & Argouslidis, 2007;

Batra & Sinha, 2000; Jin & Suh, 2005; Richardson et al., 1996; Zielke &

Dobbelstein, 2007).

Our empirical study based on two independent samples as well

as the previous literature (Levy & Gendel-Guterman, 2012) support

perceived quality as a strong direct predictor of store brand purchase

intention regardless of the brand sponsor (i.e., store brands introduced

by a hypermarket or a supermarket). For this aspect, we also found that

the perceived quality of the store brand was recorded at 2.97 to 3.15 based

on a 5-point rating scale, thus explaining the low intention to purchase

store brands (score of 2.72 to 2.94). It is also found that perceived quality

is associated with perceived price, a relative comparison between

store brand and manufacturer brand, functionality and the perceived

reliability of the store branded products.

7.2 Managerial Implications

In terms of store brand management, retail managers have to put in

more effort to create store brand awareness and a high quality image.

This study indicated that store brand awareness was not very high and

that enhancing perceived quality would increase store brand purchase

intention. Store brand awareness is critical for providing options for

consumers consideration at the preliminary stage of information

searching. This fnding provides some feedback for the marketers

regarding the effectiveness of brand promotion. Retailers must pay

attention to other cues of product quality associated with store brands,

such as packaging and brand image, as well as to the store image,

which may infuence the perception regarding the store brand quality.

Brand awareness is essentially the impression that people have of a

Perceptions and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands: Evidence

from Malaysia

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 129

companys brand. For example, retailers should also focus on store

brand communication to refect high quality.

Even though the results show that perceived price was not a key

predictor of consumers purchase intention for store brands, it should

not be ignored. The perceived price depends on the pricing strategy of

the particular retailer. Consumers who purchase store brands might

or might not pay specifc attention towards the price factor unless the

retailers specifcally highlight the price factor. Instead, the retailers

might manipulate other factors such as perceived quality and perceived

risk. With the assumption that retailers aim to keep the price a constant

factor, retailers should improve and emphasise other factors to meet

consumers expectations. However, price might not be considered to

be an independent factor; price could be integrated with other benefts

to form the perceived value and perceived quality, which would then

have an impact on purchase intention.

For retailers to reduce perceived risk, they may consider giving

a longer period of warranty and offering money-back guarantees and

free testing of the store branded products. This strategy may reduce

consumers perception of the fnancial and functional risks. Educating

the consumers and frequently exposing them to the store brands would

further reduce the perceived risks.

7.3 Limitations and Future Research

This study provides some interesting insights on consumer perceptions

of store brands; however, it is restricted to small samples. Future research

should incorporate more store brands to provide cross-validation and

allow generalisation of the results. Cross-validation will also enable the

confrmation of the research fndings obtained in this study, especially

the relationships between the tested variables, thus providing a more

in-depth explanation of store brand perception and purchase intentions.

Another limitation is that the proposed model only includes a

few potential predictors of store brand purchase intention. It would

be interesting to incorporate other related variables into the model to

provide a more comprehensive framework to understand the factors that

infuence customers perception and purchase intention towards store

brands. The variables may include characteristics of the product group,

the positioning of the store brand, attitudes regarding store brands in

general and different aspects of purchasing behaviours as suggested in

Zielke and Dobbelsteins (2007) study. Finally, the sample size in this

Siohong Tih and Kean Heng Lee

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 130

study is relatively small, and it limits the meaningful analysis of the

infuence of some key demographic variables on store brand purchase

intention. Future research might want to incorporate a larger sample

size that adopts quota sampling with reference to ethnic groups, income

and education level. This step would allow for a cross-group analysis

based on demographic characteristics in predicting shopper behaviour.

Perceptions and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands: Evidence

from Malaysia

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 131

References

Aaker, D.A. (1991). Managing Brand Equity, Simon & Schuster, New

York, NY.

Abdullah, R., Ismail, N., Abdul Rahman, A.F., Mohd Suhaimin, M.,

Safe, S.K., Mohd Tajuddin, M. T. H., Noor Armia, R., Nik Mat,

N.A., Derani, N., Samsudin, M.M., Adli Zain, R. & Sekharan Nair,

G.K. (2012). The Relationship between Store Brand and Customer

Loyalty in Retailing in Malaysia. Asian Social Science, 8(2), 171-184.

Aqueveque, C. (2006). Extrinsic cues and perceived risk: The infuence

of consumption situation. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23(5),

237-247.

Arslan, Y., Gecti, F. & Zengin, H. (2013). Examining Perceived Risk and

Its Infuence on Attitudes: A Study on Private Label Consumers in

Turkey. Asian Social Science, 9(4), 158-166.

Baltas, G. & Argouslidis, P.C. (2007). Consumer characteristics and

demand for store brands. International Journal of Retail & Distribution

Management, 35(5), 328-341.

Baltas, G. (1997). Determinants of store brand choice: A behavioural

analysis. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 6(5), 315-24.

Batra, R. & Sinha, I. (2000). Consumer-level factors moderating the

success of private label brands. Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 175-191.

Batra, R. and Homer, P.M. (2004) The Situational Impact of Brand Image

Beliefs, Journal of Consumer Psychology, 14(3), 318-330.

Beldona, S. & Wysong, S. (2007). Putting the Brand back into store

brands: An exploratory examination of store brands and brand

personality. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 16(4), 226-235.

Bettman, J.R. (1973). Perceived price and product perceptual variables.

Journal of Marketing Research, 10(1), 100-102.

Broyles, S.A., Ross, R.H., Davis, D. & Leingpibul, T. (2011). Customers

comparative loyalty to retail and manufacturer brands. Journal of

Product & Brand Management, 20(3), 205-215.

Bustos-Reyes, C.A., & Gonzalez-Benito, O. (2008). Store and store format

loyalty measures based on budget allocation. Journal of Business

Research, 61, 1015-1025.

Carpenter, J. M and Brosdahl, D. J.C. (2011) Exploring retail format

choice among US males, International Journal of Retail & Distribution

Management, 39(12), 886-898.

Carpenter, J. M., & Moore, M. (2006). Consumer demographics, store

attributes, and retail format choice in the U.S. grocery market.

Siohong Tih and Kean Heng Lee

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 132

International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 34(6),

434-452.

Churchill, G. A. (1991) Marketing Research: Methodological Foundations

(Fifth ed.). Fort Worth: The Dryden Press.

DAstous, A. & Gargouri, E. (2001). Consumer evaluations of brand

imitations. European Journal of Marketing, 35(1/2), 153-67.

De Wulf, K., Odekerken-Schroder, G., Goedertier, F. &Van Ossel, G.

(2005). Consumer perceptions of store brands versus national

brands. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 22(4), 223-232.

Diamantopoulos, A., & Schlegelmilch, B.B. (1997). Taking the Fear Out of

Data Analysis: A Step-by-Step Approach. London: The Dryden Press.

Dick, A., Jain, A. & Richardson, P. (1997). How consumers evaluate store

brands. Journal of Pricing Strategy & Practice, 5(1), 18-24.

Dick, A., Jain, A.& Richardson, P. (1995). Correlates of store brand

proneness: Some empirical observations. Journal of Product & Brand

Management, 4(4), 15-22.

Dodds, W.B., Monroe, K.B., & Grewal, D. (1991). The effects of price,

brand, and store information on buyers product evaluations.

Journal of Marketing Research, 28(3), 307-319.

Dolich, I. J. (1969). Congruence relationship between self images and

product brands. Journal of Marketing Research, 6(1), 80-84.

Finn, A. and Louviere, J. (1990), Shopping centre patronage models:

fashioning a consideration set segmentation solution, Journal of

Business Research, 21(3), 259-275.

Glynn, M.S. & Chen, S. (2009). Consumer-factors moderating private

label brand success: further empirical results. International Journal

of Retail & Distribution Management, 37(11), 896-914.

Grandhi, B., Singh, J. & Patwa, N. (2012). Navigating retail brands for

staying alive. EuroMed Journal of Business, 7(1), 66-82.

Grewal, D., Krishnan, R., Baker, J. & Borin, N. (1998). The effect of store

name, brand name and price discounts on consumers evaluations

and purchase intention. Journal of Retailing, 74(3), 331-352.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L. & Black, W. C. (1998).

Multivariate Data Analysis (Fifth Edition ed.) New Jersey: Prentice

Hall.

Hoch, S.J. & Banerji, S. (1993). When do private labels succeed? Sloan

Management Review, 34(4), 57-67.

Hsiao, C.C., Yen, H.J.R. & Li, E.Y. (2012). Exploring consumer value

of multi-channel shopping: a perspective of means-end theory.

Internet Research, 22(3), 318-339.

Perceptions and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands: Evidence

from Malaysia

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 133

Jin, B. & Sternquist, B. (2003).The infuence of retail environment on

price perceptions: An exploratory study of US and Korean students.

International Marketing Review, 20(6), 643-660.

Jin, B. & Suh, Y.G. (2005).Integrating effect of consumer perception

factors in predicting private brand purchase in Korean discount

store context. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 22(2), 62-71.

Keller, K.L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing

customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1-22.

Konus, U., Verhoef, P. C., & Neslin, S.A. (2008). Multichannel shopper

segments and their covariates. Journal of Retailing, 84(4), 398-413.

Kotler, P., Keller, K.L., Ang, S.H., Leong, S. M., & Tan, C.T. (2009).

Marketing Management: An Asian Perspective, Fifth Edition.

Singapore: Prentice Hall.

Kremer, F. & Viot, C. (2012). How store brands build retailer brand

image. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management,

40(7), 528-543.

Kremer, F. & Viot, C. (2012). How store brands build retailer brand

image. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management,

40(7), 528-543.

Kumar, V., & Karande, K.W. (2000). The effect of retail store promotion

on brand and store substitution. Journal of Business Research, 49(2),

167-181.

Levy, S. & Gendel-Guterman, H. (2012) Does advertising matter to

store brand purchase intention? A conceptual framework. Journal

of Product & Brand Management, 21(2), 89-97.

Li, Y.Q; Wang, X.H. and Yang, Z.L. (2011) The Effects of Corporate-Brand

Credibility, Perceived Corporate-Brand Origin, and Self-Image

Congruence on Purchase Intention: Evidence From Chinas Auto

Industry, Journal of Global Marketing, 24, 58-68.

Mandhachitara, R.; Shannon, R. M. and Hadjicharalambous, C. (2007)

Why Private Label Grocery Brands Have Not Succeeded in Asia.

Journal of Global Marketing, 20 (2/3), 71-87.

McDougall, G.H.G. & Levesque, T. (2000). Customer satisfaction with

services: Putting perceived value into the equation. Journal of

Services Marketing, 14(5), 392-410.

Mieres, C.G., Martin, A.M.D. & Gutierrez, J.A.T. (2006). Antecedents of

the difference in perceived risk between store brands and national

brands. European Journal of Marketing, 40(1/2), 61-82.

Mitchell, V.W. & Harris, G. (2005). The importance of consumers

perceived risk in retail strategy. European Journal of Marketing,

39(7/8), 821-837.

Siohong Tih and Kean Heng Lee

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 134

Nielsen (2008). Rising costs pave way for private label sales in Malaysia.

Retrieved on May 14, 2011, from http://my.nielsen.com/news/2008

1205.shtml.

Nielsen (2009). Malaysians are pulling in the purse strings and making

signifcant changes to their lifestyles and shopping habits. Retrieved on

May 14, 2011, from http://my.nielsen.com/news/20090701.shtml.

Phang, L.A. (2009). More Malaysians opt for store brand products. Retrieved

on July 10, 2009, from http://www.Marketing-interactive.com/

news/10029.

Piercy, N. (2012). Positive and negative cross-channel shopping

behaviour. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 30(1), 83-104.

Prasad, C. J. and Aryasri, A. R. (2011) Effect of shopper attributes on

retail format choice behaviour for food and grocery retailing in

India, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management,

39(1), 68-86

Rahman Bin Abdullah, Norhanisah Bte Ismail, Akmal Fadhila Bte Abdul

Rahman, Musnadzirah Bte Mohd Suhaimin & Siti Khadijah Bte

Safe (2012). The Relationship between Store Brand and Customer

Loyalty in Retailing in Malaysia, Asian Social Science, 8(2), 171-184.

Richardson, P.S., Dick, A.S. & Jain, A.K. (1994). Extrinsic and intrinsic cue

effects on perceptions of store brand quality. Journal of Marketing,

58, 28-36.

Richardson, P.S., Jain, A.K., & Dick, A. (1996). Household store brand

proneness: A framework. Journal of Retailing, 72(2), 159-185.

Semeijn, J., Van Riel, A.C.R. & Ambrosini, A.B. (2004).Consumer

evaluations of store brands: Effects of store image and product

attributes. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 11.247-258.

Sethuraman, R. & Cole, C. (1999). Factors infuencing the price premiums

that consumers pay for national brands over store brands. Journal

of Product & Brand Management, 8(4), 340-351.

Solomon, M.R. & Stuart, E.W. (2002). Marketing: Real People, Real Choice,

2nd ed., Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

The Edge. (22 November 2009). Building brand value. Retrieved on

December 16, 2009, from http://www.giant.com.my/media/

index/2009/11.

Tifferet, S. & Herstein, R. (2012) Need for cognition as a predictor of

store brand preferences. EuroMed Journal of Business, 7(1), 54-65.

Verhoef, P. C., Neslin, S.A. & Vroomen, B. (2007). Multichannel customer

management: Understanding the research-shopper phenomenon.

International Journal of Research in Marketing, 24, 129-148.

Perceptions and Predictors of Consumers Purchase Intentions for Store Brands: Evidence

from Malaysia

Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 6(2), 2013 135

Wang, H-M. D.; Bezawada, R. & Tsai, J.C.C. (2010) An Investigation of

Consumer Brand Choice Behavior Across Different Retail Formats,

Journal of Marketing Channels, 17, 219-242.

Wang, X.H and Yang, Z.L. (2010) The Effect of Brand Credibility on

Consumers Brand Purchase Intention in Emerging Economies: The

Moderating Role of Brand Awareness and Brand Image. Journal of

Global Marketing, 23, 177-188.

Yavas, U. (2003) A multi-attribute approach to understanding shopper

segments, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management,

31(11), 541-548.

Yoo, B.H., Donthu, N. & Lee S.H. (2000). An examination of selected

marketing mix elements and brand equity. Journal of the Academy

of Marketing Science, 28(2), 195-211.

Zeithaml, V.A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and