Professional Documents

Culture Documents

TRIPS and Public Health - Intellectual Property Rights - Trade & Development

TRIPS and Public Health - Intellectual Property Rights - Trade & Development

Uploaded by

vishwas125Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

TRIPS and Public Health - Intellectual Property Rights - Trade & Development

TRIPS and Public Health - Intellectual Property Rights - Trade & Development

Uploaded by

vishwas125Copyright:

Available Formats

TRIPS and public health

By Vishwas H Devaiah

The pharmaceutical industry is unique in that it can make exploitation appear a noble purpose.

- Dr Dale Console

My ides of a better ordered world is one in which medical discoveries would be free of patents and there would be no

profiteering from life or death

- Indira Gandhi

Public health has once again become a vital issue of concern the world over, especially in the wake of major epidemics like

HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and a host of other diseases affecting the human populace.

The Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) attempts the arduous task of balancing

private and public interests. On the one hand, it protects the interests of the pharmaceutical companies that invest heavily in

research and development of drugs and, on the other, it allows nations that belong to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) to

promote public health in their respective countries.

TRIPS, GATT & all that

TRIPS is one of the agreements under the World Trade Organisation (WTO) that nations that are members of the WTO are

supposed to adhere to. Prior to the formation of the WTO, the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs, 1947 (GATT) laid

down the rules for free trade in goods. In 1985 a new round of trade negotiations began at Panta Del Este in Uruguay which

concluded in 1994 at Marrakesh in Morocco with the formation of the WTO and the acceptance of a package of agreements

under it. Among the detailed agreements under the WTO umbrella are GATT (which establishes general rules for trade in

goods), GATS (which deals with rules in services) and TRIPS (which concerns trade in intangible property). A convention that

took place in Doha as part of a review of these agreements resulted in the Doha Declaration on Public Health.

However, patents on pharmaceutical products have adversely affected industrially developing and least developed countries,

hampering their ability to formulate appropriate public health policies that would enable their ailing citizens to access

medicines. For instance, pharmaceutical patents have raised the cost of life-saving drugs, effectively putting them out of the

reach of the majority of the world's population.

Developing and least developed countries are supposed to have the benefit of a moratorium[1] on implementing

pharmaceutical patents until the years 2005 and 2016 respectively. However, this is of little consolation[2] since the

concession has been effectively neutralised by industrially developed nations. On the one hand, they have narrowly interpreted

the flexibility provided within the agreement to promote public health so as to enable their multinational drug companies to

maximise profits.[3] On the other, they have managed to get large nations like Brazil and India to amend their patent laws and

bring them in line with the TRIPS agreement. Thus the advantages of the moratorium have been more or less nullified well

ahead of the deadlines.

The efforts of developing countries to use the mechanisms provided under TRIPS to promote public health have come under

pressure from industrialised countries and multinational pharmaceutical companies[4] in a variety of ways. For example, a

number of pharmaceutical companies challenged the South African legislation empowering the minister of health to issue

compulsory license (granting permission to a third party to manufacture a patented drug) under certain circumstances. The law

was based on the premise that expensive drugs, such as the anti retro viral (ARV) drugs used in the treatment of HIV/AIDS,

were unaffordable to large sections of society and that the consequent lack of access to drugs was leading to a serious health

crisis within the country. The action of the pharmaceutical industry against the South African initiative led to widespread

criticism of the TRIPS agreement by the developing world, NGOs and human rights activists. The controversy led to the Doha

Declaration on Public Health of November 2001.

This paper outlines the events leading up to the Doha Declaration and examines whether or not the declaration provides for

sufficient flexibility to fulfil the public health needs of all WTO member countries.

The furore over access to drugs

Once TRIPS was adopted in 1994, developing and least developed countries were obliged to effect changes in their patent

laws in accordance with the agreement. They were given time until 2000 and 2006 respectively to make the necessary

changes. But, in the meantime, they were to provide Exclusive Marketing Rights (EMR) to those who had obtained patents in

other member countries on or after the date of the entry into force of the TRIPS agreement. They were also required to create a

mechanism to enable the filing of patent applications pending the expiry of the moratorium on the implementation of

pharmaceutical patents. EMR is virtually a patent, enabling manufacturers to have the exclusive right to market their products in

a country even though the product has not been examined for novelty or non-obviousness in the country concerned.

In addition, some member countries were compelled by developed countries like the United States of America to bring their

patent laws in line with TRIPS even before the moratorium was to expire. For example, Thailand was forced to introduce

legislation on product patents long before they were legally bound to do so under the TRIPS agreement, thereby foregoing any

advantage that would have enabled them to deal with the public health crisis.

The AIDS epidemic worsened the public health situation across the world as millions of HIV-infected people in developing

countries could not access the drugs they needed because of the high cost. In theory, developing and least developed

countries in Africa with large numbers of HIV+ people could have used the TRIPS provisions recognising their right to promote

public health in order to import cheaper generic medicines from countries like India. However, they were prevented from doing

so by developed countries which held that such measures would be in contravention of the agreement. For example, the South

African decision to legitimise through compulsory licenses (ie, non-voluntary licenses granted by the government to third

parties to make the patented product) the production of generic versions of ARV as a means of addressing the problem of

access was challenged by multinational pharmaceutical companies in the country's courts.

This action drew widespread criticism from both NGOs and governments of developing countries, who alleged that TRIPS was

being used by the pharmaceutical industry to enhance profits at the cost of human lives. The controversy ultimately led to the

withdrawal of the case and catalysed a much-needed discussion on public health and intellectual property rights at the WTO's

Doha round of discussions in 2001, which culminated in a landmark declaration on public health known as the Doha

Declaration on Public Health.

Reinterpreting the objectives

The objective of the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health was to clarify the official stand on certain

provisions of TRIPS relating to public health. It recognises the concerns of developing countries and LDCs on the issue.

The Declaration clarifies that 'public health crises' can represent 'a national emergency or other circumstances of extreme

urgency', and that an 'emergency' may be either a short-term problem, or a long-lasting situation. [5] It recognises the gravity of

the public health problems afflicting many developing and least developed countries, especially those resulting from HIV/AIDS,

tuberculosis, malaria and other epidemics.[6] It accepts as legitimate concerns regarding the pricing of drugs, its effect on

access to drugs and the impact of lack of access on public health.[7] At the same time, it acknowledges that intellectual

property protection is important for the development of new medicines.

The Declaration also reiterates that the agreement should be interpreted and implemented in the light of members' right to

protect public health and promote access to medicines for all.[8] Paragraph 5(a) reiterates that each provision of the

agreement shall be interpreted in the light of its objectives and principles. According to the document, each member has the

right to determine what constitutes a national emergency or other circumstances of extreme urgency, based on the

understanding that public health crises, including those relating to HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and other epidemics, can

represent a national emergency or other circumstances of extreme urgency.[9]

However, significantly, the Doha Declaration does not define the term 'public health'. A narrow interpretation of the term would

clearly render many public health initiatives futile. While member countries are theoretically empowered by the document to

decide what constitutes a national emergency or other circumstances of extreme urgency, the possibility of a narrow

interpretation by the panel remains, leaving them at the mercy of the whims and fancies of the WTO Dispute Settlement Body.

The Doha Declaration does recognise the obvious problems faced by developing countries in promoting public health,

especially in the wake of epidemics like AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, etc. But the very fact that the document restricts itself to

certain specific epidemics creates a problem as the flexibility may be allowed only in the case of these particular diseases, if at

all. The pharmaceutical industry would certainly like to interpret this provision restrictively, leaving out certain diseases

prevalent in member countries which may not be internationally recognised as epidemics. For example, diabetes, cancer and

certain tropical diseases that are endemic in the developing world may not be given the same importance even though they

represent serious public health concerns in many countries.[10]

Another inherent defect is built into the system through the stipulation that member countries can make use of options such as

the compulsory license mechanism to promote public health only when a health crisis has arisen, especially in the form of an

epidemic affecting the populace at large. This limitation clearly weakens their right to utilise the apparent flexibility to take

preventive and precautionary action before a disease becomes a full-blown crisis.

The Declaration does recognise the problems posed by the pricing of drugs and the impact of this on access. At the same

time, it accepts the importance of intellectual property rights for the development of new medicines. Through this apparent

even-handedness it does little to reassure member countries that they can undertake action to ensure wider access to

medicines without the threat of legal disputes.

Further, the Declaration states that the agreement has to be interpreted in the light of its objectives and principles, which

means it has to be read with Articles 7 and 8 of TRIPS. Those provisions are liable to be interpreted by developed countries to

justify increased patent protection so that pharmaceutical companies can carry out research and development. R&D costs are

invariably cited as the inevitable reason for the high price of drugs, which naturally put them out of the reach of most people in

developing countries,[11] leading to the situation prior to the Doha Declaration. At the same time, pharmaceutical companies

rarely undertake research and development relating to the various diseases affecting large numbers of people in developing

countries since the products would not be profitable.

In the final analysis, by failing to clarify key terms - including 'public health' -- the Doha Declaration on Public Health leaves the

field open for their interpretation in accordance with the interests of the pharmaceutical industry and developed countries. As a

result it effectively fails to address a number of important issues and falls short of taking a clear stand on public health.

Clarification on parallel import

Parallel imports occur when a product sold by a patent holder in one country is exported by a buyer to another country where the

price for the same patented drug is higher. This effectively reduces the profits of the patent holder as the phenomenon of

parallel import usually reduces the price of the product in the country to which it is exported. For instance, if patent holder A

sells a product for $5 in country M and at $10 in country N, this is usually held to be a practice of price discrimination. If buyer B,

who acquires the product in country M exports the same product to country N and sells it there at $7, then A would be faced with

a situation where his/her own product sold in country M reduces his/her profits in country N.

Article 28 of TRIPS provides exclusive rights to the patent holder to prevent third parties from making, using, offering for sale or

importing the patented product to member countries where a patent holder has obtained patents for the same. But the footnote

to the Article subjects it to the provision in Article 6 of the TRIPS agreement, which is as follows:

"For the purposes of dispute settlement under this Agreement, subject to the provisions of Articles 3 and 4, nothing in this

Agreement shall be used to address the issue of the exhaustion of intellectual property rights."

The exhaustion of IPR rights refers to a situation wherein a patent holder is unable to use his/her exclusive rights to sell or

dispose of the patented good once the patented product has been placed in the market for sale. As a result, he/she is not in a

position to prevent any act of importation by third parties. This provision stipulates that member countries can import

pharmaceutical products from other countries only if the exclusive right is exhausted. It apparently allows developing and least

developed countries with no manufacturing capacity of their own to import drugs from countries manufacturing generic

medicines. But the problem arises with the interpretation of the doctrine of exhaustion and the question of whether domestic or

international principles of exhaustion are to be followed. Developed countries perceive this provision as a major threat, fearing

that cheaper drugs could flood their markets and undercut their profits. Thanks to their vehement opposition, the hope of

interpreting the provision in the light of the imperative of promoting public health has faded.[12] This issue was discussed in

2001 at the Doha convention which resulted in the review of Article 28 of the TRIPS Agreement.

Paragraph 5(d) of the Doha Declaration on Public Health deals with parallel importation as follows:

"Accordingly and in the light of paragraph 4 above, while maintaining our commitments in the TRIPS Agreement, we recognise

that these flexibilities include:

d. The effect of the provisions in the TRIPS Agreement that are relevant to the exhaustion of intellectual property rights is to

leave each member free to establish its own regime for such exhaustion without challenge, subject to the MFN and national

treatment provisions of Articles 3 and 4."

This provision leaves it to member countries to determine the exhaustion of intellectual property rights without discriminating

between local and foreign patent holders. A member country is, therefore, supposed to apply a single system of exhaustion of

patent rights. For instance, if a member country opts for a local interpretation of exhaustion of rights, then the same

interpretation should apply to both foreign and domestic patent holders.

Compulsory licensing

Article 31 of TRIPS enables member countries to grant the production and sale of a patent by a third party without the

authorisation of the patent holder, but limits such use predominantly for the domestic market of the member state authorising

such use. The Article reads as follows:

"Where the law of a Member allows for other use[13] of the subject matter of a patent without the authorisation of the right

holder, including use by the government or third parties authorised by the government, the following provisions shall be

respected:...

(f)any such use shall be authorised predominantly for the supply of the domestic market of the Member authorising such use."

Although the provision allows member countries to promote public health by issuing a compulsory license to a third party, it

limits the use predominantly for supply to the domestic market. As a result, member countries without local manufacturing

capacities will not be able to make use of this provision as they cannot issue licenses to manufacturers based in another

member state; nor can they import from other member states. This limitation would frustrate attempts by such countries to

promote public health by providing citizens with access to cheap medicines.

Developed country members are not in favour of compulsory licenses because they fear that generic drugs manufactured

through the use of such licenses may flow back to the patent holder's country and/or to territories where the patent is protected.

They have been very hostile towards any member country issuing compulsory license, assuming that such a step would

encourage other member countries to follow suit. The US has used the threat of sanctions as well as the dispute settlement

mechanism to prevent Brazil from amending its patent laws to allow compulsory licensing on the basis of lack of local working

of the patents.

Further, member countries are authorised such use only on certain reasonable commercial terms and conditions, in case of a

national emergency or other circumstances of extreme urgency, or in case of non-commercial use. And, in any case, the scope

and duration of such use is limited according to the purpose for which it was authorised. The agreement also envisages that

the patent holder be paid adequate remuneration, taking into account the economic value of the authorisation.[14]

The threat of being challenged and having to bear the burden of proving that a situation of national emergency or extreme

urgency existed for the grant of compulsory license has led to a situation where this provision is hardly used by developing

countries. Apart from that, since member countries can only use compulsory licensing if they face a problem of substantial

proportion -- i.e., amounting to a national emergency or a situation of extreme urgency -- the provision is of no use for preventive

measures that could help avoid such public health catastrophes.

The grant of compulsory license also involves paying suitable compensation to the patent holder. It is necessary for the

member country concerned to notify the patent holder about the grant of the compulsory license; only in situations of extreme

urgency can they issue compulsory license without notifying the patent holder. It also limits the duration of the license as it

ceases once the purpose for which it was issued, like an emergency situation or an epidemic, ceases to exit. Consequently,

the option cannot be exercised on a long-term basis to promote public health.

The Doha Declaration attempts to redress the above problems. Paragraph 4 of the Declaration says that the agreement should

be interpreted and implemented in a manner supportive of WTO members' right to protect public health and, in particular, to

promote access to medicine for all.

According to Paragraph 5 (a), a member country has the right to grant compulsory licenses and the freedom to determine the

grounds upon which such licenses can be granted. It also allows members to determine what constitutes 'national emergency'

and 'circumstance of extreme urgency'. But they have to wait until the disease reaches a scale or proportion that justifies that

kind of cataclysmic description. Even then their declaration of a national emergency invariably invites opposition from

pharmaceutical companies and developed countries which tend to question the enormity and/or seriousness of the situation.

Can a disease causing just a few deaths constitute a national emergency? Can member states use compulsory license as an

instrument of preventive action to nip a disease in the bud before it assumes epidemic proportions? These questions remain

unanswered even in the Declaration.

In addition, the Doha Declaration fails to address the fact that some countries do not have the requisite technology and/or

manufacturing capacity to take full advantage of the compulsory license provision. It has left unresolved the question of whether

compulsory licenses could be issued for importing medicines from other member countries if the concerned nation does not

have the capacity to manufacture the required drug locally. Paragraph 6 of the Doha Declaration reads as follows:

"We recognise that WTO members with insufficient or no manufacturing capacities in the pharmaceutical sector could face

difficulties in making effective use of compulsory licensing under the TRIPS Agreement. We instruct the Council for TRIPS to

find an expeditious solution to this problem and to report to the General Council before the end of 2002. "

The option of issuing compulsory license to import generic medicines from other member countries was not adopted because

the pharmaceutical industry raised objections, fearing a reduction in their profits if every country without sufficient

manufacturing capacity issued compulsory licenses to import medicines from other countries, and apprehending the

possibility of price undercuts.

This issue was supposed to be resolved by the TRIPS Council by the end of 2002, but it has not yet come up with any viable

solution to the problem. The text proposed by Mexican Ambassador Eduardo Prez Motta , chairperson of the TRIPS Council,

in December 2002 did not get the approval of developing countries as it proposed the grant of permission to countries to export

medicines to LDCs and to a very small number of developing countries that meet the test of insufficient manufacturing capacity.

The proposal suggests that there should either be no manufacturing capacity or insufficient manufacturing capacity within the

country to meet its own needs. Since this, in effect, meant that any member with some capacity to manufacture would be

ineligible to import, developing countries rejected the Motta text.

In August 2003, WTO member countries agreed that compulsory license can be issued to import generic medicines from other

countries subject to certain conditions. All the LDCs are considered to have insufficient manufacturing capacity, thus allowing

them to import medicines without notifying the TRIPS Council. However, developing countries intending to import medicines

using compulsory license have to notify the Council and prove that they have no/insufficient manufacturing capacity. The

exporting countries will have to disclose the quantity of drugs exported and distinguish them by adopting a different method of

packaging. It is important to recognise that these restricted provisions cannot be used to promote public health on a long-term

basis. An amendment to the TRIPS agreement including these provisions would be a more substantial and sustainable

development in favour of the promotion of public health.

Conclusion

The TRIPS agreement apparently provides for flexibility to member countries to implement policies and programmes to

promote public health. However, the contradictions in the agreement make it difficult for developing countries and LDCs to use

it to promote any long-term public health policy. The provisions are either too ambiguous or too vulnerable to restrictive

interpretations that serve the interests of developed countries and the pharmaceutical industry. Although some of the recent

changes in the provisions - such as those outlined in the Doha Declaration - have the potential to provide increased access to

medicines under certain, specified circumstances, TRIPS in its present form cannot, in the longer run, be used to promote

public health.

(Vishwas H Devaiah is with the Alternative Law Forum, Bangalore)

Endnotes:

1. paragraph 7 of the Doha Declaration on Public Health

2. (US-India mailbox case) referred in: Frederick.M.Abbott, (2002) "The TRIPs Agreement, Access to Medicines, and the WTO

Doha Ministerial Conference," Journal of World

3. OXFAM Report

4. Ellen 't Hoen, :TRIPS, Pharmaceutical Patents, and Access to Essential Medicines: A Long Way from Seattle to Doha

5. Carlos Correa, Implications of Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health

6. paragraph 1 of the Doha Declaration on TRIPS Agreement and Public Health

7. paragraph 3 of the Doha Declaration on TRIPS Agreement and Public Health

8. pargraph 4 of the Doha Declaration on TRIPS Agreement and Public Health

9. paragraph 5 (c) of the Doha Declaration on TRIPS Agreement and Public Health

10. Oxfam Report

11. Ellen 't Hoen, (2002), TRIPS, Pharmaceutical patents, and access to essential medicines: a long way from Seattle to Doha,

Chicago Journal of International Law

12. South African Aids Case: 39 pharmaceutical companies challenged the Article 15c of the South African Medicines and Medical

Devices Regulatory Authority Act ("Medicines Act"). This article also permitted parallel import.

13. "Other use" refers to use other than that allowed under Article 30.

14. Article3

InfoChange News & Features, May 2004

You might also like

- World Trade LawDocument17 pagesWorld Trade LawEagle PowerNo ratings yet

- Ranitidine Drug StudyDocument2 pagesRanitidine Drug StudyMarvie Cadena100% (3)

- Doha Declaration On Public HealthDocument37 pagesDoha Declaration On Public HealthAnandNo ratings yet

- Human RightsDocument15 pagesHuman RightsPhalongtharpa BhaichungNo ratings yet

- Sem I RakhiDocument23 pagesSem I RakhiJ M RashmiNo ratings yet

- Cartagana ProtocolDocument15 pagesCartagana Protocolshivanika singlaNo ratings yet

- Future Directions IoT Robotics and AI Based ApplicationsDocument29 pagesFuture Directions IoT Robotics and AI Based ApplicationsRaveendranathanNo ratings yet

- Adr FinalDocument13 pagesAdr Finalaayaksh chadhaNo ratings yet

- Greening The GattDocument15 pagesGreening The GattShubh DixitNo ratings yet

- Assignment of Ibdrm On ConciliationDocument5 pagesAssignment of Ibdrm On Conciliationdeepti tiwariNo ratings yet

- Role of The World Trade Organization: General Agreement On Trade in ServicesDocument40 pagesRole of The World Trade Organization: General Agreement On Trade in Servicessheebakapoor4No ratings yet

- Prepare Report On Human Rights Violation in India and Main Reasons Behind Its ViolationsDocument11 pagesPrepare Report On Human Rights Violation in India and Main Reasons Behind Its ViolationsAvaniJainNo ratings yet

- Health Law - AbstractDocument5 pagesHealth Law - AbstractSachi Sakshi UpadhyayaNo ratings yet

- Data Protection in India: Justice B. N. Srikrishna Report: Law of Privacy ID No. 214126Document7 pagesData Protection in India: Justice B. N. Srikrishna Report: Law of Privacy ID No. 214126Shefalika NarainNo ratings yet

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow: Project Topic-"1947 and WTO"Document14 pagesDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow: Project Topic-"1947 and WTO"Abhishek K. SinghNo ratings yet

- Food Security in India Under WTO RegimeDocument8 pagesFood Security in India Under WTO RegimeIjahss JournalNo ratings yet

- WTO D S M I C: Ispute Ettlement Echanism and Recent Ndian AsesDocument4 pagesWTO D S M I C: Ispute Ettlement Echanism and Recent Ndian AsesDharu LilawatNo ratings yet

- Free Movement of WorkersDocument12 pagesFree Movement of WorkersMaxin MihaelaNo ratings yet

- A Project On:: Hidayatullah National Law University, Raipur (C.G.)Document17 pagesA Project On:: Hidayatullah National Law University, Raipur (C.G.)MitheleshDevarajNo ratings yet

- Individual Assignment WtoDocument12 pagesIndividual Assignment WtoRaimi MardhiahNo ratings yet

- Only The Workers Can Free The Workers: The Origin of The Workers' Control Tradition and The Trade Union Advisory Coordinating Committee (TUACC), 1970-1979.Document284 pagesOnly The Workers Can Free The Workers: The Origin of The Workers' Control Tradition and The Trade Union Advisory Coordinating Committee (TUACC), 1970-1979.TigersEye99100% (1)

- Impact of GATT and WTO On Indian ForeignDocument30 pagesImpact of GATT and WTO On Indian Foreignshipra29No ratings yet

- Fair and Equitable Treatment in International Investment Law - Taxguru - inDocument6 pagesFair and Equitable Treatment in International Investment Law - Taxguru - inThaleia AndreouNo ratings yet

- MUN WTO Intellectual Property Rights Backgoround GuideDocument16 pagesMUN WTO Intellectual Property Rights Backgoround Guideshireen95No ratings yet

- The WTO Dispute Settlement System Does I PDFDocument23 pagesThe WTO Dispute Settlement System Does I PDFMoud KhalfaniNo ratings yet

- Product V Patent (2011)Document21 pagesProduct V Patent (2011)jns198No ratings yet

- International Trade LawDocument23 pagesInternational Trade LawKumar YoganandNo ratings yet

- Justice and Technological InnovationDocument13 pagesJustice and Technological Innovationqwertyw123No ratings yet

- FinalDocument24 pagesFinalshiyasethNo ratings yet

- Fdi in India PDFDocument12 pagesFdi in India PDFpnjhub legalNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Investor State Dispute Settlement ISDS in TTIPDocument153 pagesThe Impact of Investor State Dispute Settlement ISDS in TTIPbi2458No ratings yet

- Cooperation Without Harmonization: The U.S. and The European Patent SystemDocument29 pagesCooperation Without Harmonization: The U.S. and The European Patent SystemprasanNo ratings yet

- Free Movement of Eu and Non-Eu CitizensDocument6 pagesFree Movement of Eu and Non-Eu CitizensDajana GrgicNo ratings yet

- Bilateral Investment Treaties and Investment ArbitrationDocument19 pagesBilateral Investment Treaties and Investment ArbitrationAnurag DashNo ratings yet

- Effect of Wto On India: AssignmentDocument6 pagesEffect of Wto On India: AssignmentDarpan BhattNo ratings yet

- Open Challenges ListDocument2 pagesOpen Challenges ListShivam SharmaNo ratings yet

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Sabbavaram, Visakhapatnam, A.P., India Project TitleDocument10 pagesDamodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Sabbavaram, Visakhapatnam, A.P., India Project Titlesarayu alluNo ratings yet

- International Judicial Institution 1Document11 pagesInternational Judicial Institution 1AakashBagh100% (1)

- Sanjeev ITL AssignmentDocument15 pagesSanjeev ITL AssignmentashwaniNo ratings yet

- Terrorism and IHLDocument176 pagesTerrorism and IHLIon Ciobanu100% (1)

- The United Nations Ad Hoc Tribunals' Effectiveness in Prosecuting International CrimesDocument439 pagesThe United Nations Ad Hoc Tribunals' Effectiveness in Prosecuting International Crimesiihaoutreach100% (1)

- Cyber Defamation Law of Torts in IndiaDocument26 pagesCyber Defamation Law of Torts in IndiaAprajeet Ankit SinghNo ratings yet

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow Research ProposalDocument9 pagesDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow Research Proposaldivyavishal100% (1)

- Nishant Srivastav IPR Full PaperDocument16 pagesNishant Srivastav IPR Full PaperDIVYANSHI PHOTO STATENo ratings yet

- The Path Forward For Digital Asset Adoption in India PDFDocument36 pagesThe Path Forward For Digital Asset Adoption in India PDFAman ShahNo ratings yet

- Ipr in AgricultureDocument30 pagesIpr in Agriculturepeters o. JosephNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Property: Impact of Exhaustion of Intellectual Property Right On Pharmaceutical Industry in VietnamDocument26 pagesIntellectual Property: Impact of Exhaustion of Intellectual Property Right On Pharmaceutical Industry in VietnamSơn BadGuyNo ratings yet

- A Paper On Role of World Trade Organization in Protecting Intellectual Property RightsDocument8 pagesA Paper On Role of World Trade Organization in Protecting Intellectual Property Rightstrustme77No ratings yet

- Impact of WTO Policies On Developing CountriesDocument16 pagesImpact of WTO Policies On Developing CountriesShivamKumarNo ratings yet

- Copyrights Infringement Through P2P File Sharing SystemDocument18 pagesCopyrights Infringement Through P2P File Sharing Systemwalida100% (1)

- ILA Public Policy Interim ReportDocument36 pagesILA Public Policy Interim ReportViorel ChiricioiuNo ratings yet

- The Power of One: The Law Teacher in The Academy - Amita DhandaDocument15 pagesThe Power of One: The Law Teacher in The Academy - Amita DhandaAninditaMukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Patent - AssignmentDocument18 pagesPatent - AssignmentGeeta SahaNo ratings yet

- P Har Mind 230611Document221 pagesP Har Mind 230611drpramoNo ratings yet

- International Investment Law TextbookDocument10 pagesInternational Investment Law TextbookChloe SteeleNo ratings yet

- Handbook On European Law Relating To Asylum, Borders and ImmigrationDocument257 pagesHandbook On European Law Relating To Asylum, Borders and ImmigrationBoglarka NagyNo ratings yet

- Criminal & Security LawDocument6 pagesCriminal & Security LawPrashant SinghNo ratings yet

- Ibc 2016 MDocument11 pagesIbc 2016 MMayank SenNo ratings yet

- Reflections on the Debate Between Trade and Environment: A Study Guide for Law Students, Researchers,And AcademicsFrom EverandReflections on the Debate Between Trade and Environment: A Study Guide for Law Students, Researchers,And AcademicsNo ratings yet

- Trade PrestationDocument1 pageTrade PrestationManikanta MahimaNo ratings yet

- Final ProjectDocument10 pagesFinal ProjectManikanta MahimaNo ratings yet

- Noramco - Small-Volume Manufacture of Active Pharmaceutical IngredientsDocument4 pagesNoramco - Small-Volume Manufacture of Active Pharmaceutical IngredientsEdgardo Ed Ramirez100% (1)

- Principles of Practice For Pharmaceutical CareDocument29 pagesPrinciples of Practice For Pharmaceutical CareNgetwa TzDe TheWirymanNo ratings yet

- Final Hydrogen-Peroxide ReportDocument9 pagesFinal Hydrogen-Peroxide ReportAshley PeridaNo ratings yet

- Major DTR 1Document1 pageMajor DTR 1GeraldineMoletaGabutinNo ratings yet

- Dry Powder Coating A New Trend in Coating TechnologyDocument11 pagesDry Powder Coating A New Trend in Coating TechnologyTimir PatelNo ratings yet

- Adrenergic NS 2Document43 pagesAdrenergic NS 2Abdullah Muhammed khaleel HassanNo ratings yet

- Hypertension Nursing Care Plan..nkDocument16 pagesHypertension Nursing Care Plan..nkchishimba louisNo ratings yet

- SOP On Procedure For Microbiological Monitoring of Purified Water in Pharmaceutical CompanyDocument3 pagesSOP On Procedure For Microbiological Monitoring of Purified Water in Pharmaceutical CompanyReza JafariNo ratings yet

- Cannabis Use and MisuseDocument28 pagesCannabis Use and MisuseBenedict BothNo ratings yet

- Mu CostaDocument6 pagesMu Costafarracholidia_867630No ratings yet

- Storage and Distribution PracticeDocument32 pagesStorage and Distribution PracticeAlaeldeen AhmedNo ratings yet

- Article1380726732 - Akhtar 20et 20alDocument11 pagesArticle1380726732 - Akhtar 20et 20alTakeshi MondaNo ratings yet

- DHR International: ConfidentialDocument5 pagesDHR International: ConfidentialDisha Kansara ChawlaNo ratings yet

- Expanding The Medicinal Chemistry Synthetic ToolboxDocument19 pagesExpanding The Medicinal Chemistry Synthetic ToolboxPhoebeliza Jane BroñolaNo ratings yet

- Biotechnology and BioinformaticsDocument513 pagesBiotechnology and BioinformaticsMichael J GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Laporan - Data - Obat - Habis NovemberDocument42 pagesLaporan - Data - Obat - Habis NovemberaristhanovyraNo ratings yet

- 17425247.20113. Oral Formulation StrategiesDocument18 pages17425247.20113. Oral Formulation StrategiesPaqui Miranda GualdaNo ratings yet

- 400 3 NarcoticsDocument27 pages400 3 Narcoticsfirdaus92No ratings yet

- Alexander ShulginDocument42 pagesAlexander Shulginrapidfire0070% (1)

- Combinatorial and Parallel SynthesisDocument55 pagesCombinatorial and Parallel SynthesisMahfuz AlamNo ratings yet

- RevisedFinalStemBook2006 SaadDocument170 pagesRevisedFinalStemBook2006 SaadKarn Patel100% (1)

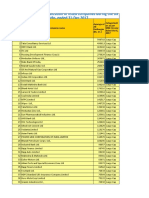

- Avg. Market Capitalization of Listed Companies During - Jul-Dec 2017Document117 pagesAvg. Market Capitalization of Listed Companies During - Jul-Dec 2017Anish ShahNo ratings yet

- Your World Biotechnology and You Vol 13-1 R20070820WDocument16 pagesYour World Biotechnology and You Vol 13-1 R20070820WAdelin AnastasiuNo ratings yet

- MiconazoleDocument3 pagesMiconazoleapi-3797941No ratings yet

- Pharmaceutical Industry in Pakistan: January 2017Document9 pagesPharmaceutical Industry in Pakistan: January 2017Zia ul IslamNo ratings yet

- MichaudDocument3 pagesMichaudADSDNo ratings yet

- Quality by Design Process Analytical Technology: (QBD) & (PAT)Document45 pagesQuality by Design Process Analytical Technology: (QBD) & (PAT)Sharon DsouzaNo ratings yet

- Superol Kpo Tds 2012Document1 pageSuperol Kpo Tds 2012rusyadNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic - Dog, Cat, Fish, Bird, Horse, ReptileDocument3 pagesAntibiotic - Dog, Cat, Fish, Bird, Horse, ReptilecomgmailNo ratings yet